As early as January 1979, Stuart Hall, who coined the term ‘Thatcherism’, wrote: ‘No one seriously concerned with political strategies in the current situation can now afford to ignore the “swing to the Right.”’ That year, as was later shown,Footnote 1 marked the high point of the British electorate’s rightward movement – and the ‘sea change’ (as Jim Callaghan called it) in public opinion that was marked by the election of the Thatcher government. For many, Thatcher’s ‘authoritarian populism’ captured the nation’s anxious mood in the economic crisis of the mid-to-late 1970s in the aftermath of the upswing in industrial militancy and the cultural radicalism of the ‘permissive society’ of the 1960s and early 1970s.Footnote 2 The Left was divided in Britain and unable to exploit the social liberalism of the previous decade to articulate a relevant progressive political discourse. Thatcher was still in office when Ivor CreweFootnote 3 posed the question of whether the British electorate had ‘become Thatcherite’. Subsequent studies analysed Thatcher’s Children and the extent to which this generation was more right wing relative to predecessors, and found mixed evidence.Footnote 4

In this article we examine the question of political generations by analysing the extent to which a political context marked by a right-authoritarian zeitgeist influenced the values of new cohorts. While this wider theoretical question is applicable to other comparative contexts such as the United States under Reagan and the rise of the Moral Majority, in this article we use British data since the prolonged period of Conservative rule in Britain between 1979 and 1997 provides an excellent test case for examining the theory of political generations and formative experiences. Normally we would expect younger generations to be more leftist and liberal than older generations. Therefore the protracted period with the Conservative Party in office allows us to test whether younger cohorts coming of age in this political context came to adopt political attitudes in line with those of this party at a greater rate than would be expected given their age. Further, our investigation builds on this traditional question by examining whether the generation that came of age under New Labour, ‘Blair’s Babies’, can be better identified as ‘Thatcher’s Grandchildren’, in reinforcing the rightward shift in social values that had occurred under the previous generation.

We postulate a ‘trickle-down’Footnote 5 theory of social change: during the first phase of Conservative government (normative neoliberalism) there was deeper ideological contestation, while in the second phase (normalized neoliberalism) even political opponents and rival partisans had internalized its market precepts as ‘the rules of the game’. The 1980s were marked by a concentrated political shift towards neoliberal market economies in many Western democracies.Footnote 6 The rise of the New Right signalled a rightward shift in opinion in the United States, United Kingdom and other Anglo-American democracies in the 1980s. As such, we seek to gauge whether those who came of age under Thatcher and subsequent prime ministers are more politically conservative than those who came of age earlier, when such values were more frequently contested.

In short, the question addressed in this article is: To what extent did the generations coming of age in the protracted period of Conservative government come to exhibit more conservative values? What were the differences between the generation that came of age in the first phase (during Thatcher’s time in office) relative to the second phase (after she left office, during the time of New Labour)? We theorize that ‘Thatcher’s Children’ may be less Thatcherite than ‘Blair’s Babies’, as Thatcherite values became entrenched across society – as signalled by New Labour’s emergence – after she left office.Footnote 7

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. We first discuss theories of generational replacement and value change and develop our hypotheses. We then discuss the data and methods used in this study of attitudinal change in Britain: specifically, a newly combined longitudinal dataset built from repeated cross-sectional sweeps of the British Social Attitudes survey for the period from 1985 to 2012.Footnote 8 These are used to identify and isolate the different effects of age, period and cohort on social values. We next present our results concerning the degree to which generations socialized during and after Thatcher was prime minister differ in their attitudes to redistribution, welfare and authority. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of the implications of these findings for our understanding of the Thatcher years and their legacy, and reflect on their wider significance for the study of the evolution of social and political attitudes and long-term processes of socialization.

POLITICAL GENERATIONS

Generational theories share the idea that values are formed early on, are influenced by the specific historical and political contexts within which each new cohort of citizens is socialized, and remain stable throughout the life course, so that aggregate value change occurs as older cohorts with certain value sets die and are replaced by younger cohorts with different values.Footnote 9 One such type of account is modernization theory.Footnote 10 However, while modernization theory allows for some short-term shifts in values, the theory suggests that social liberalism should become increasingly widespread at the aggregate level, given underlying secular trends.Footnote 11 In contrast, political generations theory takes a historicized perspective that emphasizes the importance of political events and experiences taking place during the impressionable ‘formative years’ to different cohorts.Footnote 12 According to this line of thinking, it is not so much affluence and security in childhood that shapes the values and political commitments of new cohorts, but rather the political experiences and historical events occurring during one’s young adulthood. Various studies have shown that diverse political contexts can produce generations with distinct value sets and patterns of behaviour.Footnote 13 Critical historical moments such as the worldwide student protests of 1968 or the fall of the Berlin Wall, a prolonged period during which the same party holds power, and other types of major external events during a cohort’s coming of age are understood to explain why socialization in diverse political contexts creates distinct ‘political generations’. While members of a given political generation are divided by social cleavages such as gender and class (MannheimFootnote 14 calls these ‘generation units’), nonetheless, as a generation, they are understood to share the same values and conceptions of the world because they emerged from the same temporal/spatial location. MannheimFootnote 15 thus likens generations to social classes arising from distinct positions in the economic or material realm.Footnote 16 While some studies of macro-level preferences have shown how publics react thermostatically to the government of the day,Footnote 17 others have argued that parties in government are able to shape the preferences of the electorateFootnote 18 which would be consistent with the effect of socialization on political values during certain periods.

‘THATCHER’S CHILDREN’

GambleFootnote 19 characterizes Thatcherism as a marriage of ‘the free economy and the strong state’ – a flexible synthesis, in other words, of market liberalization (support for a smaller state, deregulation of financial markets, privatization of publicly owned industries and assets, the sale of council houses) and social conservatism with a strengthened law and order agenda (Clause 28, extending police powers, facing down trade unions as ‘the enemy within’, a tougher rhetorical stance on sentencing, Cold War rearmament). In this conception, Thatcherism sought to establish a hegemonic project involving ‘ideology, economics and politics, a politics of support and a politics of power’.Footnote 20 Hall saw Thatcherism as more than simply ‘the corresponding political bedfellow of a period of capitalist recession’ but as a dramatic rupture from the politics of the social-democratic post-war consensus.Footnote 21 Gilroy and Simm pointed out how the main innovation with respect to ‘law and order’ during the Thatcher governments was to politicize and present the repressive state institutions as necessary instruments in the fight against certain ‘subversive’ elements in society and winning support for this from large sections, if not the majority, of the British public.Footnote 22 The politicization of ‘law and order’ was a crucial break brought forth by the Thatcher governments, and the appeal of populism was understood as a key reason why almost a third of trade unionists voted for the Conservatives in May 1979.Footnote 23 Thatcher’s emphasis on the politics of confrontation and pitting different social sectors against each other to garner support through ‘divide-and-rule’ strategies was most commonly associated with the reaction to the inner-city riots in 1981 and the Miners’ Strike in 1984–85. In many ways, the Thatcher governments of this period were quite distinctive and presented themselves as breaking from the post-war consensus. The Conservatives were in office continuously for eighteen years between 1979 and 1997 (under Margaret Thatcher until 1990, and then under John Major), the longest unbroken period of rule by one party in the UK since 1830. These factors combined would suggest a strong influence on the values of young people coming of age in this political context.

Early research on the impact of Thatcherism on British public attitudes began by looking at straightforward, over-time change. For example, CreweFootnote 24 explored whether the electorate had become more focused on self-reliance, and found decreasing enthusiasm for this idea. The turning point in the research on the attitudinal impact of Thatcherism came with Russell et al.’sFootnote 25 pioneering study, which was the first to examine the political socialization of ‘Thatcher’s Children’ and generational effects. They showed that while ageing had a tendency to increase Conservative identification, the formative experiences of electoral generations resulted in persistent cohort differences. Russell et al.Footnote 26 concluded that socialization during Thatcher’s term in office meant that first-time voters in the 1979 and 1987 elections were more likely to support the Conservatives than would have been expected given their age. This study showed that examining the imprint on the youngest generations and the impact of political socialization was an important aspect to consider when analysing whether Thatcher had changed Britain’s values.

Later, Heath and ParkFootnote 27 showed some signs of a Thatcherite generational shift, finding evidence that the 1980s generation was more materialistic than previous generations. Examining cohort differences in British Election Study data, TilleyFootnote 28 showed that the younger cohorts’ tendency to move away from the Conservatives was reversed in the 1980s and 1990s. Later, Tilley and HeathFootnote 29 showed how Thatcher was able to arrest the decline in feelings of national pride and the trend towards more liberal young generations.Footnote 30 Tilley and EvansFootnote 31 recently showed how the generations coming of age in periods of Conservative ascendancy (the 1930s, 1950s and 1980s) were all more likely to support this party.

It was not until the late 1990s that aggregate studies of public opinion began to show a Thatcherite shift, supporting the idea of a process of underlying generational replacement at play. Curtice and JowellFootnote 32 provide evidence that between 1985 and 1996 fewer people agreed that government should provide healthcare, pensions, control prices, help industry grow, help poor families send their children to university, provide shelter for the poor, reduce inequality, provide jobs or help the unemployed. Evidence from the British Social Attitudes Survey showed that the proportion of the electorate agreeing that ‘governments ought to redistribute income’ had fallen from 45 per cent in 1987 to 36 per cent in 2009, while the proportion saying ‘government ought to spend more on benefits’ fell from 55 per cent in 1987 to 27 per cent in 2009.Footnote 33

‘THATCHER’S GRANDCHILDREN’?

Since Major did not set out to openly challenge Thatcher’s policies, we expect that the socialization experiences of young people coming of age during his time in office should not have differed substantially from those coming of age under Thatcher’s governments. The emergence of New Labour under Tony Blair signalled that while it was internally divided, Labour had also moved closer to the Thatcher agenda primarily as the result of an ideological move dictated by the party leadership.Footnote 34 Particularly from the inception of New Labour in 1994, all three main parties were converging on a recognizably Thatcher-influenced ‘middle ground’, so that the primacy of the market became the accepted wisdomFootnote 35 and Thatcherite polices were consolidated by Blair.Footnote 36 Since New Labour has come to be widely understood as ‘Thatcherism by another name’Footnote 37 and its values even less contested than when she was in office, we test the proposition that the values of the generation coming of age between 1997 and 2010 will be even more right wing and authoritarian than those of previous generations. Based on the discussion above, we test the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: The cohort that came of age between 1979 and 1996 will be more right wing and more authoritarian than cohorts that came of age prior to this prolonged period of Conservative rule.

Hypothesis 2: The cohort that came of age under New Labour between 1997 and 2010 will be more right wing and more authoritarian than cohorts that came of age before them.

DATA AND METHODS

The analysis in this article relies on British Social Attitudes survey data for the period between 1985 and 2012. These are repeated cross-sectional surveys in which respondents were asked the same attitudinal and other questions at different points in time. The dataset was constructed specifically for the purposes of this type of analysis.Footnote 38 It thus provides rich individual-level data on social attitudes and political values relevant to Thatcherism as well as all the necessary control variables over a sufficiently long time span to separate age, period and cohort effects.

Dependent Variables

While most studies on the generation politically socialized under Thatcher have examined partisanship or just a few available indicators of left–right and libertarian–authoritarian values, in this study we examine nine different indicators of right-authoritarian values side by side. In each case the survey item has been recoded so that a value of 1 indicates agreement with the Thatcherite position and a value of 0 indicates disagreement. This allows direct comparisons across indicators, and means that in the results an increasing trend suggests greater agreement with the Thatcherite stance in the same way across all indicators.Footnote 39 The variables tap into both left–right economic and libertarian–authoritarian social values. More specifically, the following nine dependent variables are analysed in this study:

1. What do you think about the income gap between the rich and the poor in the UK today? (1=About Right, Too Small; 0=Too Large)

2. Government should redistribute from the better off to the less well off. (1=Disagree, Strongly Disagree; 0=Neither, Agree, Strongly Agree)

3. Government should spend more money on the poor even if it leads to higher taxes. (1=Disagree, Strongly Disagree; 0=Neither, Agree, Strongly Agree).

4. Opinions differ about the level of benefits for the unemployed. Which of these best reflects your opinion? (1=Benefits are too high and discourage people from finding jobs; 0=Other response categories i.e. Benefits are too low and cause hardship, Neither, Both cause hardship, Some people benefit, Some people suffer, About right, Other)

5. The unemployed could find a job if they wanted to. (1=Agree, Strongly Agree; 0=Neither, Disagree, Strongly Disagree)

6. People should learn to stand on their own feet. (1=Agree, Strongly Agree; 0=Neither, Disagree, Strongly Disagree)

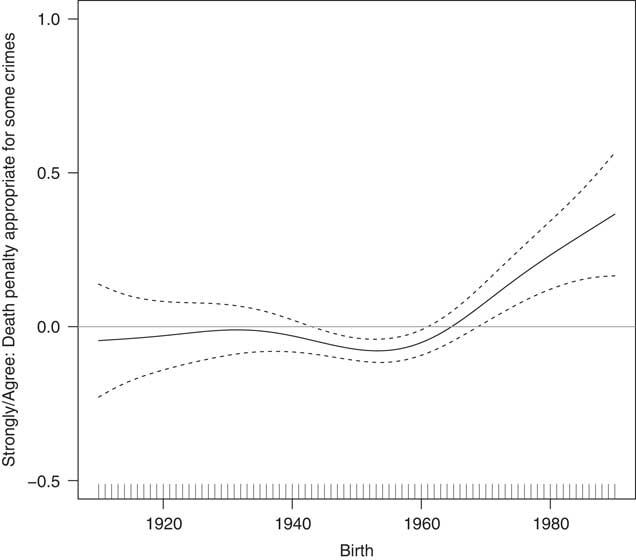

7. The death penalty is appropriate for some crimes. (1=Agree, Strongly Agree; 0=Neither, Disagree, Strongly Disagree)

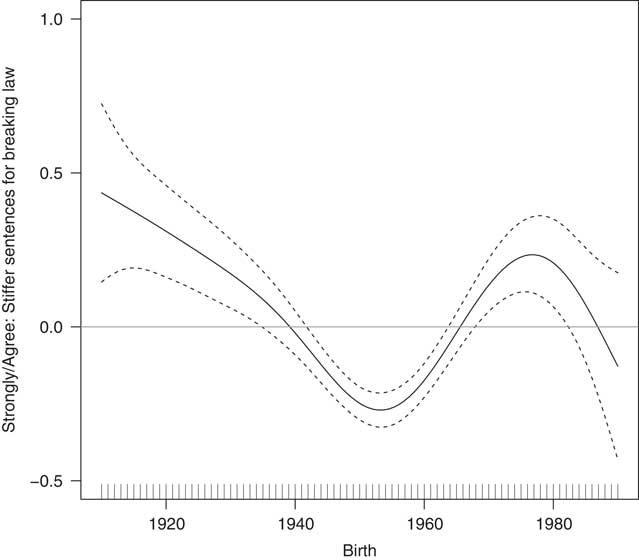

8. People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences. (1=Agree, Strongly Agree; 0=Neither, Disagree, Strongly Disagree)

9. Schools should teach children to obey authority. (1=Agree, Strongly Agree; 0=Neither, Disagree, Strongly Disagree)

AGE-PERIOD-COHORT MODELLING STRATEGY

Generational theories, such as those discussed earlier, tend to argue that the context of one’s socialization is the most important factor for understanding differences in values relative to age or period effects. However, research on cohort effects needs to address the potentially confounding influences of age and period effects when estimating the models. Age effects suggest that values change as individuals age, and indeed research has found that older people tend to be more conservative than younger people. Moreover, certain periods signal a rightward shift for all individuals in society, such as the period of Thatcher’s ascendancy in Britain. Therefore in order to identify cohort effects, we also need to control for both age and period, or year of survey, in our models. This issue is known as the age-period-cohort ‘identification problem’ in the literature. It emerges since the three effects are in a linear relationship with each other. As soon as we know two values, we simultaneously know the third:

In order to ‘identify’ the model and capture net effects it is necessary to apply certain restrictions. This methodological hurdle has meant that a rich statistical literature has emerged over the years presenting methods to ‘solve’ the identification problem.Footnote 40 In this article, we follow the method presented in Grasso,Footnote 41 which consists of applying generalized additive models (GAMs) to plot the identified, smoothed cohort effect as well as testing for intergenerational differences using constrained age-period-cohort models and post-estimation Wald tests. Since the data employed are from a single country, we do not need to apply generalized additive mixed models (GAMMs) in this context but can safely rely on non-hierarchical generalized additive models (GAMs), using the continuous year of birth variable to plot the smoothed cohort effect in order to overcome the identification problem. Moreover, to test for cohort differences we apply Wald tests after estimating age-period-cohort regression models using a categorized cohort variable, reflecting the theoretical distinctions based on the historical period of socialization.

The GAMs allow us to plot the nonlinear smoothed cohort effect since year of birth is estimated as smoothly changing. There are different smoothing functions that could be applied; smoothing splines are used here, and the software package selected the smoothing parameter by generalized cross-validation. This allows us to plot the non-parametric smoothed curve for the effect of year of birth.Footnote 42 The utility of the application of the GAMs is that it permits us to visually check whether cohort effects are what we would expect based on the categorized generations variable from the age-period-cohort (APC) models. Arriving at the same results using two different methods and applying different types of restrictions gives us greater confidence in our results. This combined method for dealing with the identification problem is particularly appropriate here, as it has been developed specifically for research questions examining political generations with repeated cross-sectional attitudinal data, which are typical in political science.Footnote 43 GAMs are particularly useful for examining the non-linear components of generational effects. Other approaches, such as the intrinsic estimator (IE) and hierarchical APC (HAPC) models developed in demography and epidemiology, are not employed here since they are less suited to the current type of data structure and research questions.Footnote 44 Simulation studies have shown that these methods run the risk of incorrectly attributing trends in age, period or cohort to the other two terms.Footnote 45 Moreover, Luo shows that IE relies on arbitrary and unjustified constraints.Footnote 46 However, we combine constrained APC models and GAMs, which allows us to clearly test our hypotheses by applying the theoretically derived cohort groupings as well as checking the results for robustness.

Given that we are interested in cohort differences, year of birth is the main independent variable. This ranges from 1910 to 1990. The idea of a ‘Thatcher effect’ implies that the generations socialized during the period of her ascendancy will be particularly right-authoritarian. The key period of socialization will largely depend on the mechanism implied in theory.Footnote 47 Given that here we are examining the formation of political attitudes as a result of the ascendancy of a party in government, we would expect that socialization should occur from the mid-teens to the mid-to-late twenties. We use the method presented in GrassoFootnote 48 to assign individuals to different political generations based on the historical phase in which they spent the majority of their formative years. As such, we define Thatcher’s Children as those born between 1959 and 1976 and coming of age in the protracted period of Conservative rule between 1979 and 1996 (we include 1997 in the following period). Descriptions of the political generations analysed in this study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Political Generations

* This period includes the Conservative Heath government of 1970–1974.

** This period also includes Major’s period in office between 1990 and 1997.

*** This period includes the Blair and Brown governments.

This method of categorizing generations has the advantage that it emphasizes the historical period of a generation’s socialization. The years of birth of the political generations are then derived from this information. We include the categorized political generations variable in the APC models in order to (1) cross-check the robustness of the results from the GAMs and (2) use Wald tests to test for cohort differences. In the GAMs we use the continuous year of birth variable to derive the smoothed cohort effects. In addition to year of birth/cohort, we also include age and period to identify the APC models. The description of variables henceforth applies to both the GAMs and APC models. Age is coded as a three-level factor: (1) thirty-four years and under, (2) thirty-five to fifty-nine years or (3) sixty years and over. Year of survey is included as a continuous variable. To test the robustness of the cohort effects, we ran the APC models with a number of alternative configurations of age and period.

Other Variables

We control for gender as well as education level, marital status, employment status, household income, whether or not the respondent attended private school, home ownership, union membership and Conservative Party identification. In each case we use the most detailed measures available in the over-time longitudinal file.Footnote 49 Descriptive statistics for all these variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Variable Descriptive Statistics

Other than generation, younger age and higher education levels tend to be linked to greater liberalism.Footnote 50 Younger cohorts are more likely to be highly educated and therefore more liberal than older cohorts. Modernization theorists argue that the expansion of education leads to greater liberalism among younger cohorts and therefore society as a whole through inter-generational replacement. As such, controlling for education and student status should allow us to capture the generational differences resulting from socialization as opposed to differences that can be attributed to other sorts of characteristics that should make younger cohorts more socially liberal.Footnote 51 While modernization theory implies that the shift from materialist to post-materialist values primarily occurs due to cohort replacement over time, in this way we can also control for some compositional changes.

Controls for marital status (married, previously married or single/never married) and employment status (full-time employment, part-time employment, unemployed/waiting for work, retired, student, taking care of the home or other employment situation) are included to account for aspects of social ageing and structural position.Footnote 52 They also deal with the issue that married people tend to be more conservative but that younger generations are less likely to settle into conventional family arrangements than previous generations. Moreover, since some of the items pertain to unemployment benefits, it is necessary to control for whether someone is seeking work. Students and women are also generally more liberal groups, whereas those retired from employment tend to be more conservative; as such, including gender and employment status in the models represent helpful controls.

Class is an important variable for understanding social differences in political values. In Britain, the middle classes have traditionally tended to associate with the Conservative Party, whereas the working classes have tended to support Labour. This picture has become more complex with class dealignment and the waning relevance of values concerning inequality and redistribution in political discourse, which traditionally translated class divisions into party choice.Footnote 53 In any case, we would expect individuals in the middle class to be generally more likely to hold right-wing economic values,Footnote 54 though the picture for authoritarianism is less clear. We also include three additional measures of privilege and social status – household income (low, mid, high), whether the respondent attended private school and home ownership – since more privileged individuals are more likely to defend inequality for obvious reasons, and this might be reflected in the composition of different cohorts. We also include controls for union membership and Conservative Party identification in order to address compositional differences between cohorts.

ANALYSIS

First we estimate APC models with our categorized cohort variable (as presented in Table 1). Next, in order to formally test whether certain political generations are more Thatcherite than others, we ran Wald tests. While the APC logistic regression models presented in Table 3 allow us to see whether differences between each cohort included in the model and the reference category (‘Wilson/Callaghan’s Children’) are significant, Wald tests allow us to test for coefficient differences between the cohort categories included in the model. The results for the Wald tests are presented in Table 4.

Table 3 APC Models: Right-Authoritarian Values

Note: standard errors in parentheses. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

Table 4 Wald Tests for Intergenerational Differences from APC Models

Note: a significant result implies cohort differences between each given pair in the rows for each of the dependent variables in the columns. See coefficients in Table 3 for direction of effects. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001

While the controls generally exhibit the expected effects, gender does not have a consistent effect on either economic or social values. As expected, married individuals are more conservative than both previously married and single individuals. The same is true of individuals in full-time employment relative to all the other employment categories. As expected, individuals in the higher income categories are more Thatcherite with respect to redistribution, inequality, benefits and attitudes towards the unemployed. However, they are also less authoritarian than those with lower incomes. Having a private education is associated with being more Thatcherite with respect to redistribution and inequality. However, it also linked with being less likely to agree with the negative sentiments about benefits and the unemployed, and with being less authoritarian. As expected, home ownership tends to predict Thatcherism as (unsurprisingly) does party identification, whereas union membership decreases the likelihood that one will agree with Thatcherite values.

Class is an interesting variable. Compared to the middle class, all the other classes are less likely to agree that the income gap is too small or about right. The working class is more likely than the middle class to agree that government should redistribute. However, there are no class differences for the survey item that suggests a trade-off between redistribution and taxation. Interestingly, controlling for all other variables in the models, all three items on benefits and all three items on authoritarianism show that all other classes are more likely to agree with the Thatcherite tendency than the upper middle class, which supports the populist story line.

Turning to the APC results, first it should be noted that there are some small age effects: the middle age group is more likely than the younger group to support redistribution if it entails higher taxes, to express more positive views of the unemployed and to disagree that the death penalty is appropriate for some crimes. Those in the oldest age group are less likely to agree with the Thatcherite position on redistribution than the youngest age group, but are more likely to think poorly of benefit seekers and to want children to be taught to obey authority. The effects for year of survey show that, with the exception of the inequality item, there are significant period effects with increasing support for the Thatcherite position in all cases except support for the death penalty. This suggests that, over a period of twenty or more years, the electorate indeed became more Thatcherite, particularly with respect to negative attitudes about the benefits system, the unemployed, benefit recipients and the welfare system more generally.

The coefficients for political generations in the APC models presented in Table 3, in conjunction with the results from the Wald tests presented in Table 4, show that across eight of nine indicators, Thatcher’s Children are more right wing and authoritarian than the generation preceding them (Wilson/Callaghan’s Children). This provides support to Hypothesis 1. Blair’s Babies are also more right wing and authoritarian than this political generation, confirming that Thatcherite values were reproduced under New Labour, and become stronger and embedded in the generation that came of age after Thatcher’s time in office. This is consistent with Hypothesis 2. Thatcher’s Children and Blair’s Babies are even more right wing economically than the generation that came of age before the post-war consensus. Blair’s Babies in particular are almost as negative about benefits and the welfare system as the generation that came of age before it was created. They are also nearly as authoritarian as the oldest generations, showing that the trend toward modernization and greater social liberalism was at least slowed down in Britain under the Thatcher governments.

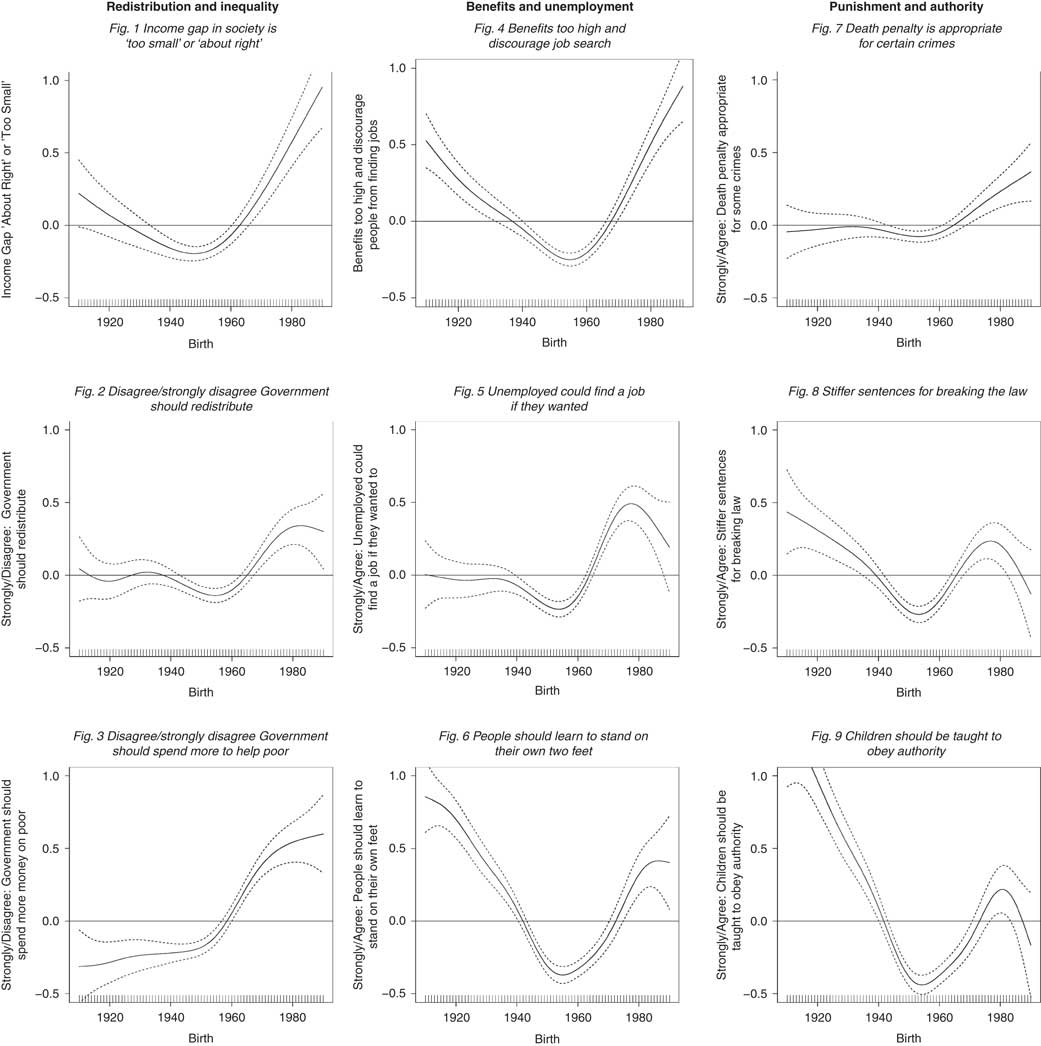

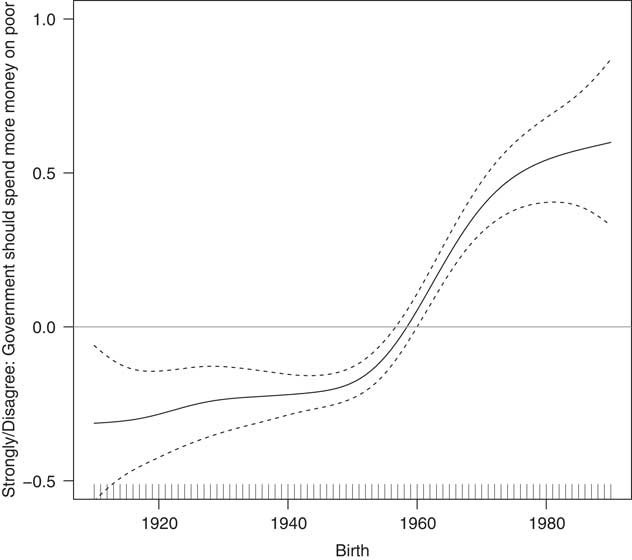

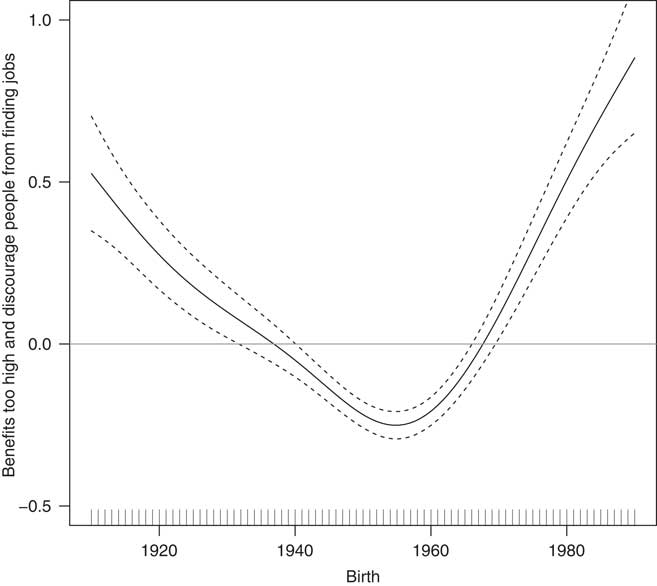

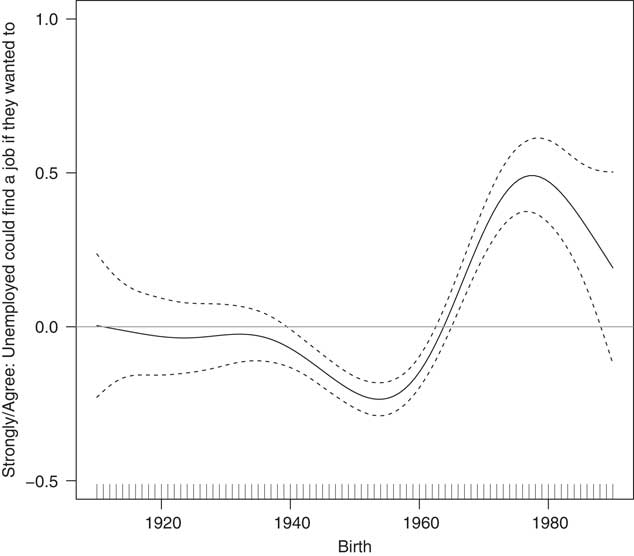

As explained in the data and methods section, in order to provide robustness tests for the results from the APC models, we next examine the visual results from the GAMs. In particular, we examine the plots of the smoothed cohort effect from the full model (not shown) with the same controls included as in the APC models. These plots are presented in Figure 1–9.Footnote 55

The patterns are striking and consistent. Across the plots for the smoothed cohort effects all nine indicators, there is an upward swing in right-authoritarian values from around the start of the years of birth of the Thatcherite political generation (that is, those born in 1959) at least up until the end of it (those born in 1976), and in several cases lasting well beyond. This suggests Thatcherite values were growing in strength among the cohort that became political adults during the Thatcher years. With the exception of two of the nine figures, one can see an upswing during the birth years of Thatcher’s Children, thus reversing the trend towards greater support for redistribution and social egalitarianism observed for previous political generations (the cohorts born before 1959). This provides clear support for the theoretical expectation of a ‘Thatcher effect’ (Hypothesis 1). It is especially noticeable that the curve bends upwards and commences the increasing trend precisely at the end of the 1950s (the birth years of the oldest of Thatcher’s Children).

While the curve during the birth years of Thatcher’s Children does not always return to the levels of the pre- and early consensus generations, there is a tendency towards greater conservatism that starts with Thatcher’s Children (those born 1959–76) across all nine indicators. With respect to the political generation born between 1977 and 1990 (that is, Blair’s Babies or Thatcher’s Grandchildren), we find that in some cases the upward trend continues, for example on the income gap between rich and poor (Figure 1) and the beliefs that benefits are too high (Figure 4) and that the death penalty is appropriate for some crimes (Figure 7). In other cases, however, there is a counter-tendency and it looks like the trend might level off or even reverse, such as for whether people who break the law should be given stiffer sentences (Figure 9), although the confidence intervals are typically too wide to be certain at the time of writing. More years of data are needed to clarify trends in social values among the youngest members of this new political generation. Regardless, with respect to attitudes on redistribution (Figures 1–3) the curve ends at a higher point than its level during the birth years of the pre- and early consensus generations, providing evidence that Blair’s Babies are a distinctly right-wing cohort in their economic values, which is consistent with Hypothesis 2. Moreover, with respect to authoritarian values, Thatcher’s Children exhibit a slowing down and reversal of the modernization tendency towards greater social liberalism, which is consistent with Hypothesis 2. In particular, with respect to support for inequality, redistribution and particularly redistribution versus taxation, but also attitudes towards the unemployed/benefits, Thatcher’s Children and Blair’s Babies are more right wing than any of the three older generations. This provides considerable support for our theoretical expectations.

We thus find mixed support for each hypothesis. With respect to the first hypothesis, the results confirm that Thatcher’s Children are indeed more right wing and authoritarian than the generation preceding them, the more liberal Wilson/Callaghan’s Children. This is true when we examine eight out of nine attitudinal variables capturing different dimensions of Thatcherite beliefs. Thatcher’s period in office reversed the generational trend in social values. With respect to the second hypothesis, we find evidence that Blair’s Babies are also more right wing and authoritarian than Wilson/Callaghan’s Children. They are also more economically right wing than both the pre- and early consensus generations, but not more socially authoritarian than either. Overall then, Blair’s Babies stand out as the most economically right-wing generation; they are also more authoritarian than Thatcher’s Children. Our models thus show that the generation coming of age in the aftermath of the Cold War, once Thatcher had left office, stands out as the most economically conservative, net of both period and age effects. Overall, the results provide some support for the idea of a political generation of ‘Thatcher’s Children’, since with this cohort we see a reversal of the trend towards greater social liberalism and support for redistribution. These results also suggest that rendering Thatcherite values uncontentious (under Blair) was more significant for ensuring their long-term endurance.

To test whether it was Labour Party identifiers in particular who moved to the right under Blair,Footnote 56 we included an interaction effect of Labour Party identification with Blair’s Babies. This interaction effect was significant for the three redistribution and inequality indicators as well as for the three welfare items. However, this was not the case for the three authoritarian values indicators. These results therefore show that it was the generation coming of age under New Labour and identifying with this party that moved to the right. This further strengthens the conclusion that Blair achieved more than Thatcher had done in terms of cementing her principles in British society, and that this was achieved through Labour supporters embracing more right-wing positions as these became mainstream and uncontested in society.Footnote 57 We also ran a series of interaction tests with various socio-demographic and regional variables that showed that the generational differences were generally consistent across groups.Footnote 58

CONCLUSIONS

The results presented in this article offer strong evidence of cohort effects. We have shown that generations coming of age under sustained periods of Conservative government absorb these values, offsetting the tendency towards social liberalism that is normally characteristic of youth. More specifically, since we examined British data, we showed that the generation that came of political age during Thatcher and Major’s time in office is particularly conservative, and deserving of the epithet ‘Thatcher’s Children’. But we have not just found more evidence of ‘Thatcher’s Children’; we have also discovered her ‘Grandchildren’ in ‘Blair’s Babies’.

We analysed indicators of Thatcherite values across three dimensions – redistribution and inequality, benefits and unemployment, punishment and authority – and found that this generation (born between 1959 and 1976) reversed the cohort trend towards greater support for redistribution and more social liberalism. This pattern is largely continued in the subsequent generation of Thatcher’s Grandchildren, which supports the idea that Thatcherite values were reproduced, not challenged, under New LabourFootnote 59 . Our analyses showed that Blair’s Babies are even more right-authoritarian. It seems that the trend towards ever-greater social liberalism was halted and even reversed, supporting the idea that Thatcherism has fundamentally changed British social attitudes in an enduring way. The timing of the upward trend in the GAM-smoothed cohort effect plots coincided with the birth years of Thatcher’s Children. This occurs at the same time across indicators. By disentangling APC effects using new statistical techniques and analysing a long time series of attitudinal data, we have shown that Thatcher’s crusade successfully promoted and consolidated economic as well as social values. Her moral crusade was extremely successful at changing the values of the generation that came of age at that time, and at influencing society to such an extent that New Labour came to accept these as setting the ideational parameters of political competition.

How these trends in social values unfold will also be enlightening, and only time will tell whether the fragmentation of the British party system, fallout from the economic crisis, the era of austerity and the outcome of the referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union will influence these trajectories. These results may also be relevant to other countries that have experienced protracted periods of conservative rule and where the New Right was popular, such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States.Footnote 60 It is likely that comparable political environments will have had similarly formative impacts on newer political generations. There are implications for modernization theory and for what sorts of events might provide counter-tendencies to the ‘inexorable logic’ of greater tolerance and social liberalism.

Most importantly, this article shows that particularly significant events such as the protracted rule of one party followed by a centrist shift towards that party’s position from the opposition are important ‘formative experiences’ for new generations. Moreover, we have also shown that such changes can have spillover effects by reproducing certain values when subsequent governments or parties in power do not challenge the values that formed that generation. This trickle-down theory of social change can explain why Thatcherite attitudes are still more prevalent in ‘Blair’s Babies’ or ‘Thatcher’s Grandchildren’. This is a clear sign that Thatcher changed the course of British politics and social attitudes. Her values - or the values that have come to be associated with her name - permeate British society today as subsequent governments have not challenged her ideology. For better or worse, it seems that we still live in ‘Thatcher’s Britain’.

Fig. 1–9 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs).

Fig. 2 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs). Disagree/strongly disagree, Government should redistribute

Fig. 3 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs). Disagree/strongly disagree Government should spend more to help poor

Fig. 4 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs). Benefits too high and discourage job search

Fig. 5 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs). Unemployed could find a job if they wanted

Fig. 6 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs). People should learn to stand on their own two feet

Fig. 7 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs). Death penalty is appropriate for certain crimes

Fig. 8 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs). Stiffer sentences for breaking the law

Fig. 9 Smoothed cohort effects from generalized additive models (GAMs). Children should be taught to obey authority