No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

At Global Affairs Canada in 2022

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 November 2023

Abstract

- Type

- Canadian Practice in International Law/Pratique canadienne en matière de droit international

- Information

- Canadian Yearbook of International Law/Annuaire canadien de droit international , Volume 60 , November 2023 , pp. 292 - 338

- Copyright

- © The Canadian Yearbook of International Law/Annuaire canadien de droit international 2023

Footnotes

The extracts from official correspondence contained in this survey have been made available by courtesy of Global Affairs Canada. Some of the correspondence from which extracts are given was provided for the general guidance of the enquirer in relation to specific facts that are often not described in full in the extracts within this compilation. The statements of law and practice should not necessarily be regarded as definitive.

References

1 United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) Sixth Committee, International Law Commission Report, Canada Statement – Cluster 1, 28 October 2021, at 3, (https://www.un.org/en/ga/sixth/76/pdfs/statements/ilc/19mtg_canada_1e.pdf).

2 Council of Europe (CoE) and the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL), eds, Treaty Making – Expression of Consent by States to be Bound by a Treaty (The Hague: Kluwer Law, 2001) at 301 Google Scholar.

3 “Text of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement – Chapter thirty: Final provisions” Government of Canada (http://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/ceta-aecg/text-texte/30.aspx?lang=eng).

4 Canada–European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement Implementation Act S.C. 2017, c. 6; see also “Order Fixing September 21, 2017 as the Day on which the Act Comes into Force, other than Certain Provisions” Canada Gazette <https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2017/2017-09-07-x1/html/si-tr47-eng.html>.

5 See, for example, Note no. JLI – 0133 regarding General Coordination Agreement between the United States of America and Canada on the Use of the Radio Frequency Spectrum by Terrestrial Radiocommunication Stations and Earth Stations (2021).

6 See Juan Manuel Gómez-Robledo, Second Report on the Provisional Application of Treaties, UN Doc A/CN.4/675 (2014) at para 84.

7 Sean D. Murphy explains that “[w]hile the draft guideline [on provisional application] identifies these other forms, virtually all agreements on provisional application may be found in the treaty itself that is being provisionally applied or in a separate treaty; very few (if any) examples may be found of provisional application in the form of a resolution adopted at an international organization or by a declaration of a state accepted by others.” See Sean D. Murphy, “Provisional Application of Treaties and Other Topics: The Seventy Second Session of the International Law Commission” (2021) 115:4 AJIL 671, at 673; see also ILC, Guide to the Provisional Application of Treaties, with commentaries thereto, UNGAOR, 76th Sess, Supp No 10, UN Doc A/76/10 (2021) at 62, Guidelines 3 and 4.

8 See Trade Agreement between Canada and Spain, E100588 – CTS 1955/12, art X(c); Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of Peru for Air Services between and beyond their respective territories, E103280 – CTS 1955/1, art XIV; Trade Agreement between Canada and Mexico, E100538 – CTS 1946/4, art VIII(2); Trade Agreement between Canada and Brazil, E102985 – CTS 1941/18, art X(2); Trade Agreement between Canada and Chile, E102997 – CTS 1941/16, art IX(2).

9 See Free Trade Agreement between Canada and the States of the European Free Trade Association (Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland), CTS 2009/3, art 41.

10 See, for example, Exchange of Notes between Canada and Sweden providing for the Provisional Application between the two countries of the Provisions of the International Air Services Transit Agreement done at Chicago, December 7, 1944 (now terminated).

11 See, as an example, Exchange of Notes (September 23 and October 9 and 12, 1942) Between Canada and Chile Extending the Provisional Application of the Trade Agreement of September 10, 1941, E104697 – CTS 1942/15; cf Trade Agreement between Canada and Chile (E102997 – CTS 1941/16), art IX (2).

12 See Protocol Additional to the Agreement between Canada and the International Atomic Energy Agency for the Application of Safeguards in Connection with the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, art 17(b).

13 See Statement by Canada, UNGA, 70th Session, Sixth Committee, 25th Meeting, UN Doc A/C.6/70/SR.25 (2015) at para 60.

14 See Memorandum by the ILC Secretariat on Provisional Application of Treaties, UNGA, ILC, 69th session, UN Doc A/CN.4/707, at para 103.

1 Sixième Commission de l’Assemblée générale des Nations Unies (AGNU), Rapport de la Commission du droit international, Déclaration du Canada – Groupe 1, 27 octobre 2021, p 3 (https://www.un.org/en/ga/sixth/76/pdfs/statements/ilc/19mtg_canada_1.pdf).

2 Conseil de l’Europe et Institut britannique de droit international et de droit comparé (BIICL), Conclusion des traités – Expression par les États du consentement à être liés par un traité, La Haye, Kluwer Law, 2001, à la p 301.

3 Gouvernement du Canada, Texte de l’Accord économique et commercial global – Chapitre trente : Dispositions finales (https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/ceta-aecg/text-texte/30.aspx?lang=fra).

4 Loi de mise en œuvre de l’Accord économique et commercial global entre le Canada et l’Union européenne, L.C. 2017, ch. 6; voir aussi le Décret fixant au 21 septembre 2017 la date d’entrée en vigueur de la loi, à l’exception de certaines dispositions, Gazette du Canada, (https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2017/2017-09-07-x1/html/si-tr47-fra.html).

5 Voir, par exemple, la Note no JLI – 0133 sur l’Accord général de coordination entre le Canada et les États‑Unis d’Amérique concernant l’utilisation du spectre des fréquences radioélectriques par les stations de radiocommunication de Terre et les stations terriennes, 2021.

6 Voir Juan Manuel Gómez-Robledo, Deuxième rapport du Rapporteur spécial sur l’application provisoire des traités, Doc NU A/CN.4/675 (2014) au para 84.

7 Sean D. Murphy explique que [Traduction] « […] même si le projet de directive [sur l’application à titre provisoire] mentionne ces autres formes, la quasi-totalité des dispositions prévoyant que les parties conviennent d’appliquer provisoirement un traité se trouvent dans le traité devant faire l’objet de cette application, ou encore dans un traité distinct; il n’existe que peu ou pas d’exemples d’une application à titre provisoire résultant d’une résolution adoptée par une organisation internationale ou d’une déclaration d’un État acceptée par un autre État ». Voir Sean D. Murphy, «Provisional Application of Treaties and Other Topics: The Seventy Second Session of the International Law Commission» (2021) 115:4 AJIL 671, 673 [en anglais seulement]; voir aussi CDI, Guide de l’application à titre provisoire des traités et commentaires y relatifs, directives 3 et 4.

8 Voir l’article X(3) de l’Accord de commerce entre le Canada et l’Espagne, F100588 – RTC 1955/12; voir aussi l’article XIV de l’Accord entre le Gouvernement du Canada et le Gouvernement du Pérou relatif aux services aériens entre leurs territoires respectifs et au-delà de ces territoires, F103280 – RTC 1955/1; l’article VIII(2) de l’Accord commercial entre le Canada et le Mexique, F100538 – RTC 1946/4; l’article X(2) de l’Accord commercial entre le Canada et le Brésil, F102985 – RTC 1941/18; et, enfin, l’article IX(2) de l’Accord commercial entre le Canada et le Chili, F102997 – RTC 1941/16.

9 Voir l’article 41 de l’Accord de libre-échange entre le Canada et les États de l’Association européenne de libre‑échange (Islande, Liechtenstein, Norvège et Suisse), RTC 2009/3.

10 Voir, par exemple, l’Échange de notes entre le Canada et la Suède concernant l’application provisoire entre les deux pays de l’Accord relatif au transit des services aériens internationaux fait à Chicago le 7 décembre 1944 (cet accord n’est plus en vigueur).

11 Voir, par exemple, l’Échange de notes (23 septembre, 9 et 12 octobre 1942) entre le Canada et le Chili comportant un Accord portant prorogation de l’application provisoire de l’Accord commercial du 10 septembre 1941, F104697 – RTC 1942/15; cf. article IX(2) de l’Accord commercial entre le Canada et le Chili, F102997 – RTC 1941/16.

12 Voir l’article 17b) du Protocole additionnel à l’Accord entre le Canada et l’Agence internationale de l’énergie atomique relatif à l’application de garanties dans le cadre du Traité sur la non-prolifération des armes nucléaires.

13 Voir la Déclaration du Canada, Assemblée générale des Nations Unies,70e session, Sixième Commission, 25e séance, Doc NU A/C.6/70/SR.25, paragr. 60.

14 Voir l’Étude du secrétariat de la CDI sur l’application provisoire des traités, Assemblée générale des Nations Unies, Commission du droit international, 69e session, Doc NU A/CN.4/707, paragr. 103.

1 For a broader discussion on legally binding and non-legally binding instruments at international law, see Daniel Bodansky, “Legally binding versus non-legally binding instruments”, Geneva Reports on the World Economy, 2015-November, 155-165, available online: <https://asu.pure.elsevier.com/en/publications/legally-binding-versus-non-legally-binding-instruments>.

2 See Draft conclusions on subsequent agreements and subsequent practice in relation to the interpretation of treaties (2018), Draft Conclusion 11(2), available online: <https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/1_11_2018.pdf>.

3 See Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, arts 15(5)(c) and 17.

4 See International Law Commission, Draft conclusions on subsequent agreements and subsequent practice in relation to the interpretation of treaties, with commentaries, Commentary to Draft Conclusion 11(2) para 11, page 85, available online: <https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/commentaries/1_11_2018.pdf>.

5 See International Law Commission, Draft conclusions on subsequent agreements and subsequent practice in relation to the interpretation of treaties (2018), Draft Conclusions 4 and 7, available online: <https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/draft_articles/1_11_2018.pdf>.

1 Although cyberspace has no single agreed upon definition, it consists of interdependent networks of information technology structures—including the Internet, telecommunications networks, computer systems, embedded processors and controllers—as well as the software and data that reside within them: Canada Defence Terminology Standardization Board (DTSB) (2016).

2 This framework is based on the applicability of international law to State activities; voluntary, non-binding norms; and the development and implementation of practical confidence building measures to help reduce the risk of conflict stemming from cyber activities.

3 United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), Report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, UNGAOR, 68th Sess, UN Doc A/68/98*(2013) (2013 GGE Report) (later adopted by the UNGA Resolution A/RES/68/243); UNGA, Report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the Field of Information and Telecommunications in the Context of International Security, UNGAOR, 70th Sess, UN Doc A/70/174 (2015) (2015 GGE Report) (later adopted by the UNGA Resolution A/RES/70/237); UNGA, Report of the Open-ended working group on developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security, UN Doc A/75/816 (2021) (2021 OEWG Report); UNGA, Report of the Group of Governmental Experts on Advancing Responsible State Behaviour in Cyberspace in the Context of International Security, 76th Sess, UN Doc A/76/135 (2021) (2021 GGE Report) (both later adopted by UNGA Resolution A/RES/76/19).

4 Statements by Canada during the informal consultative meeting of the Group of Governmental Experts on Advancing Responsible State behaviour in Cyberspace in the context of international security (2019), online: <www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/statements-canada-informal-consultative-meeting-gge-5-6-december.pdf>.

5 2021 GGE Report, supra note 3; Official compendium of voluntary national contributions on the subject of how international law applies to the use of information and communications technologies by States submitted by participating governmental experts, at 73; The NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence, International cyber law: interactive toolkit (2022), online: <https://cyberlaw.ccdcoe.org/wiki/Category:National_position>.

6 2021 OEWG Report, supra note 3 at 36-37, 39-40.

7 Charter of the United Nations (UN Charter), 26 June 1945 Can TS 1945 No.7, online: <https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/full-text>.

9 Chair’s Summary, OEWG, 3rd substantive session, Annex, UN Doc A/AC.290/2021/CRP.3* (2021) 10-15.

10 2021 OEWG Report, supra note 3 at 25.

11 Island of Palmas (or Miangas) Case: United States v Netherlands, Award, (1928) 2 RIAA 829, ICGJ 392 (PCA 1928), 4th April 1928, Permanent Court of Arbitration [PCA], online: <https://legal.un.org/riaa/cases/vol_II/829-871.pdf>.

12 R. v. Hape, 2007 SCC 26 (CanLII), [2007] 2 SCR 292, online: <https://canlii.ca/t/1rq5n>.

13 Ibid at 43.

14 International law provides for exceptions to the rule on territorial sovereignty such as those actions (i) authorised by the United Nations Security Council; (ii) taken in self-defence in relation to an armed attack; (iii) consented to by the affected State; or (iv) that constitute countermeasures. These exceptions apply in cyberspace.

15 Schmitt, Michael N., Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Operations, 2d ed (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017) at 20 para. 10 [hereinafter Tallinn Manual 2.0].

16 Of note, espionage, while not per se wrongful under international law, could be carried out in a way that might violate international law. See generally Tallinn Manual 2.0, supra note 15, Rule 4 and its discussion of cyber espionage at 19 paras 7-9.

17 For example, in Canada economic espionage is a violation of section 19 of the Security of Information Act (R.S.C. 1985, c.O-5), and every person who commits an offence under subsection 19(1) is guilty of an indictable offence and is liable to imprisonment for a term of not more than 10 years.

18 Inherently sovereign functions (also known as domaine réservé) include those matters in which a State may decide freely, such as political, economic, social, and cultural systems, as well as the formation of foreign policy.

19 Tallinn Manual 2.0 supra note 15, Rule 66 and accompanying commentary at 318 para 19, provides that “mere coercion does not suffice to establish a breach of the prohibition of intervention…[it] must be designed to influence outcomes in, or conduct with respect to, a matter reserved to a target State.”

20 See the discussion of the voluntary, non-binding UN GGE norms in the 2021 UN GGE Report, supra note 3 at 29-30, 42-46. Canada does not consider that the UN GGE consensus in 2015, and subsequently, on voluntary, non-binding norms touching on this matter precludes the recognition of a binding legal rule of due diligence under customary international law. Canada continues to study this matter.

21 A State may also engage international responsibility if it coerces another state or directs and controls it in the commission of an internationally wrongful act: International Law Commission, Draft Articles on Responsibility of States for Internationally Wrongful Acts (Articles on State Responsibility), with commentaries, (2001) Arts. 17, 18, online: <https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/commentaries/9_6_2001.pdf>.

22 Articles on State Responsibility, supra note 21,Art. 8.

23 Articles on State Responsibility, supra note 21, Art. 22.

24 In this regard the law of state responsibility foresees cases where notification may not be required – Articles on State Responsibility, supra note 21, Art. 52(b).

25 Government of Canada, Human rights and inclusion in online and digital contexts (2022), online: <https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/human_rights-droits_homme/internet_freedom-liberte_internet.aspx?lang=eng>.

26 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), 16 December 1966, 999 UNTS 171, online: <https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights>.

28 UN Charter, supra note 7, Art. 2(4).

29 UN Charter, supra note 7, Art. 51.

30 Tallinn Manual 2.0, supra note 15, Rule 80 at 375.

31 Tallinn Manual 2.0, supra note 15, Rule 92 at 415; see also generally Article 49(1) of the Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and Relating to the Protections of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 8 June 1977, 1125 UNTS 3, online: <https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/protocol-additional-geneva-conventions-12-august-1949>.

33 The views of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) are a valuable reference on this point: ICRC, Cyber operations during armed conflict are not happening in the a ‘legal void’ or ‘grey zone’-they are subject to the established principles and rules of international humanitarian law: Statement by the International Committee of the Red Cross to the UN Security Council Open Debate on Cyber Security, maintaining international peace and security in cyberspace (2021), online: <https://www.icrc.org/en/document/cyber-operations-during-armed-conflict-are-not-happening-legal-void-or-grey-zone-they-are>; ICRC, The ICRC calls on all States to affirm that IHL applies to, and therefore restricts, cyber operations during armed conflicts: Statement to the Group of Governmental Experts on Advancing responsible State behaviour in cyberspace in the context of international security, Informal Consultative meeting (2021), online: <https://www.icrc.org/en/document/icrc-calls-all-states-affirm-ihl-applies-and-therefore-restricts-cyber-operations-during>.

1 Bien qu’il n’existe pas de définition unique universellement acceptée de la notion de cyberespace, celui-ci se compose de réseaux interdépendants de structures de technologie de l’information – comprenant l’Internet, les réseaux de télécommunications, les systèmes informatiques et les processeurs et contrôleurs intégrés – ainsi que des logiciels et des données qui y sont contenus. Canada, Conseil de normalisation de la terminologie de la défense, 2016.

2 Ce cadre repose sur l’applicabilité du droit international aux activités des États, sur des normes facultatives et non contraignantes, ainsi que sur l’élaboration et la mise en œuvre de mesures de confiance concrètes pour contribuer à la réduction du risque de conflit découlant des cyberactivités.

3 Assemblée générale des Nations Unies (AGNU), Rapport du Groupe d’experts gouvernementaux chargé d’examiner les progrès de l’informatique et des télécommunications dans le contexte de la sécurité internationale, documents officiels de l’AGNU, 68e session, Doc NU A/68/98* (2013) (ci-après Rapport du GEG 2013) (adopté ultérieurement par la résolution A/RES/68/243 de l’AGNU); AGNU, Rapport du Groupe d’experts gouvernementaux chargé d’examiner les progrès de l’informatique et des télécommunications dans le contexte de la sécurité internationale, documents officiels de l’AGNU, 70e session, Nations Unies, Doc NU A/70/174 (2015) (ci-après Rapport du GEG 2015) (adopté ultérieurement par la résolution A/RES/70/237 de l’AGNU); AGNU, Rapport du Groupe de travail à composition non limitée chargé d’examiner les progrès de l’informatique et des télécommunications dans le contexte de la sécurité internationale, Doc NU A/75/816 (2021) (ci-après Rapport du GTCNL 2021); et AGNU, Rapport du Groupe d’experts gouvernementaux chargé d’examiner les moyens de favoriser le comportement responsable des États dans le cyberespace dans le contexte de la sécurité internationale, 76e session, Doc NU A/76/135 (2021) (ci-après Rapport du GEG 2021) (les deux ont été adoptés ultérieurement par la résolution A/RES/76/19 de l’AGNU).

4 Déclarations du Canada lors de la réunion consultative informelle du Groupe d’experts gouvernementaux chargé d’examiner les moyens de favoriser le comportement responsable des États dans le cyberespace dans le contexte de la sécurité internationale (2019) [en anglais seulement], accessible à l’adresse : <https://www.un.org/disarmament/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/statements-canada-informal-consultative-meeting-gge-5-6-december.pdf>.

5 Rapport du GEG 2021, supra, note 3; Recueil officiel des contributions nationales volontaires sur la question de savoir comment le droit international s’applique à l’utilisation des technologies de l’information et des communications par les États, soumises par les experts gouvernementaux participants, paragr. 73; Centre d’excellence pour la cyberdéfense de l’OTAN, Droit international du cyberspace : trousse d’outils interactifs(2022) [en anglais seulement], accessible à l’adresse: <https://cyberlaw.ccdcoe.org/wiki/Category:National_position>.

6 Rapport du GTCNL 2021, supra note 3, paragr. 36-37, 39-40.

7 Charte des Nations Unies,26 juin 1945 R.T. Can. TS 1945 no 7, accessible à l’adresse : <https://www.un.org/fr/about-us/un-charter/full-text>.

9 Résumé du président, GTCNL, troisième session de fond, annexe, Doc NU A/AC.290/2021/CRP.3* (2021), paragr. 10-15 [en anglais seulement].

10 Rapport du GTCNL 2021, supra, note 3, paragr. 25.

11 Cour permanente d’arbitrage, Affaire de l’île de Palmas (ou Miangas), Les États-Unis c. Les Pays-Bas, sentence arbitrale, II RIAA 829, ICGJ 392, 4 avril 1928 [en anglais seulement], accessible à l’adresse : <https://legal.un.org/riaa/cases/vol_II/829-871.pdf>.

12 R. c. Hape, 2007 CSC 26 (CanLII), accessible à l’adresse: <https://canlii.ca/t/1rq5p>.

13 Ibid., paragr. 43.

14 Le droit international prévoit des exceptions à la règle de souveraineté territoriale telles que les actions i) autorisées par le Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies, ii) prises en état de légitime défense face à une attaque armée, iii) auxquelles l’État touché a consenti, ou iv) qui constituent des contre-mesures. Ces exceptions s’appliquent dans le cyberespace.

15 Schmitt, Michael N., Tallinn Manual 2.0 on the International Law Applicable to Cyber Operations, 2e éd., Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2017, p. 20, paragr. 10 [en anglais seulement] (ci-après Tallinn Manual 2.0).

16 Il convient de signaler que l’espionnage, bien qu’il ne soit pas en soi illicite au regard du droit international, peut être réalisé d’une manière susceptible de violer le droit international. Voir, de manière générale, Tallinn Manual 2.0, supra, note 15, règle 4 et passage sur le cyberespionnage à la p. 19, paragr. 7-9.

17 Par exemple, au Canada, l’espionnage économique constitue une violation de l’article 19 de la Loi sur la protection de l’information (L.R.C. 1985, c. O-5), et toute personne qui commet une infraction visée au paragraphe 19(1) est coupable d’un acte criminel passible d’un emprisonnement maximal de 10 ans.

18 Les fonctions intrinsèquement souveraines (aussi appelées « domaine réservé ») comprennent les matières à propos desquelles l’État peut se décider librement, comme les systèmes politiques, économiques, sociaux et culturels, ainsi que la formulation de la politique étrangère.

19 Tallinn Manual 2.0, supra, note 15, règle 66 et commentaire connexe à la p. 318, paragr. 19, selon lequel [traduction] « la contrainte à elle seule ne suffit pas pour établir que l’interdiction d’intervenir a été violée […] elle doit aussi viser à influer sur l’issue d’une question relevant exclusivement de l’État touché ou sur la conduite de celui‑ci à cet égard ».

20 Voir les commentaires sur les normes facultatives et non contraignantes du GEG des Nations Unies dans le Rapport du GEG 2021, supra, note 3, paragr. 29-30 et 42-46. Le Canada ne considère pas que le consensus qui s’est dégagé au sein du GEG des Nations Unies en 2015, et depuis lors, sur des normes facultatives et non contraignantes en la matière empêche la reconnaissance d’une règle juridique contraignante de diligence raisonnable en droit international coutumier. Le Canada continue d’étudier cette question.

21 Un État peut également engager sa responsabilité internationale s’il contraint un autre État à commettre un fait internationalement illicite, ou donne des directives et exerce un contrôle dans la commission d’un fait internationalement illicite par un autre État : Commission du droit international, Projet d’articles sur la responsabilité de l’État pour fait internationalement illicite et commentaires y relatifs 2001, art. 17 et 18, accessible à l’adresse: <https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/french/commentaries/9_6_2001.pdf>.

22 Ibid., art. 8.

23 Ibid., art. 22.

24 À cet égard, le droit de la responsabilité des États prévoit des cas où la notification peut ne pas être requise : ibid., art. 52 b).

25 Gouvernement du Canada, Droits de la personne et inclusion dans les contextes en ligne et numériques (2022), accessible à l’adresse: <https://www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/issues_development-enjeux_developpement/human_rights-droits_homme/internet_freedom-liberte_internet.aspx?lang=fra>.

26 Pacte international relatif aux droits civils et politiques (PIDCP), 16 décembre 1966, 999 UNTS 171, accessible à l’adresse: <https://www.ohchr.org/fr/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights>.

28 Charte des Nations Unies, supra, note 7, art. 2(4).

29 Charte des Nations Unies, supra, note 7, art. 51.

30 Tallinn Manual 2.0, supra, note 15, règle 80, p. 375.

31 Tallinn Manual 2.0, supra, note 15, règle 92, p. 415. Voir aussi, de manière générale, l’article 49(1) du Protocole additionnel aux Conventions de Genève du 12 août 1949 relatif à la protection des victimes des conflits armés internationaux (Protocole I), 8 juin 1977, 1125 UNTS 3, accessible à l’adresse : <https://www.ohchr.org/fr/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/protocol-additional-geneva-conventions-12-august-1949-and>.

33 Les avis du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (CICR) jettent un éclairage précieux sur ce point. Selon le CICR, [traduction] « Les cyberactivités menées lors d’un conflit armé ne se produisent pas dans un “vide juridique” ou une “zone grise” - elles sont assujetties aux règles et principes établis du droit international humanitaire » : CICR, Déclaration du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge dans le cadre du débat ouvert du Conseil de sécurité des Nations Unies sur la cybersécurité et le maintien de la paix et de la sécurité internationales dans le cyberespace(2021) [en anglais seulement], accessible à l’adresse: <https://www.icrc.org/en/document/cyber-operations-during-armed-conflict-are-not-happening-legal-void-or-grey-zone-they-are>. De plus, le CICR [traduction] « appelle tous les États à affirmer que le DIH s’applique, et impose donc des limites, aux cyberactivités menées durant les conflits armés » : CICR, Déclaration adressée au Groupe d’experts gouvernementaux chargé d’examiner les moyens de favoriser le comportement responsable des États dans le cyberespace dans le contexte de la sécurité internationale, Réunion consultative informelle (2021) [en anglais seulement], accessible à l’adresse : <https://www.icrc.org/en/document/icrc-calls-all-states-affirm-ihl-applies-and-therefore-restricts-cyber-operations-during>.

1 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 397, (entered into force 16 November 1994).

3 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, art. 77(3).

4 Cases concerning the delimitation of the continental shelf of the North Sea (Federal Republic of Germany v Denmark and Federal Republic of Germany v Netherlands), [1969] ICJ Rep 3 at 19.

5 Case concerning the delimitation of the maritime boundary in the Bay of Bengal (Bangladesh v Myanmar), [2012] ITLOS Rep 4 at 407.

6 CLCS, 21st Sess, 58th Mtg, CLCS/40/Rev.1 (2008) (Rules of Procedure).

7 Decision regarding the workload of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf and the ability of States, particularly developing States, to fulfil the requirements of article 4 of annex II to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, as well as the decision contained in SPLOS/72, paragraph (a), SPLOS/183, 20 June 2008, [online] <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00908320903510084>.

8 Ibid, art 1(1) of Annex III.

9 Ibid, rule 45(2).

10 Ibid, Annex I; Ibid, rule 50.

11 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, supra note 1, art 2(2) and art 2(4) of Annex II.

12 CLCS, supra note 6, rule 23.

13 Ibid, para III(6) of Annex III.

14 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, supra note 1, art 8 of Annex II.

15 Ibid, art 3 of Annex II.

16 Ibid, art 76(10).

17 Ilulissat Declaration, 28 May 2008, (Canada/Denmark/Norway/Russia/United States), online: <https://arcticportal.org/images/stories/pdf/Ilulissat-declaration.pdf>.

18 ROP, rule 46 and para 5(a) of Annex I

21 Report of the Secretary-General, UNGAOR, 57th session, Supp No 49, UN doc A/57/57/Add.1, (2002), 1 at 41.

22 CLCS/68, paragraph 57

23 Canada’s 2019 ECS Outer Limits, at 16 <https://www.un.org/depts/los/clcs_new/submissions_files/can1_84_2019/CDA_ARC_ES_EN_secured.pdf>.

24 Agreement between the United States of America and the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics on the Maritime Boundary, United States and Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, June 1, 1990, 106 US Stat 5162, <https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/US_Russia_1990.pdf>.

25 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, supra note 6, art 76(4).

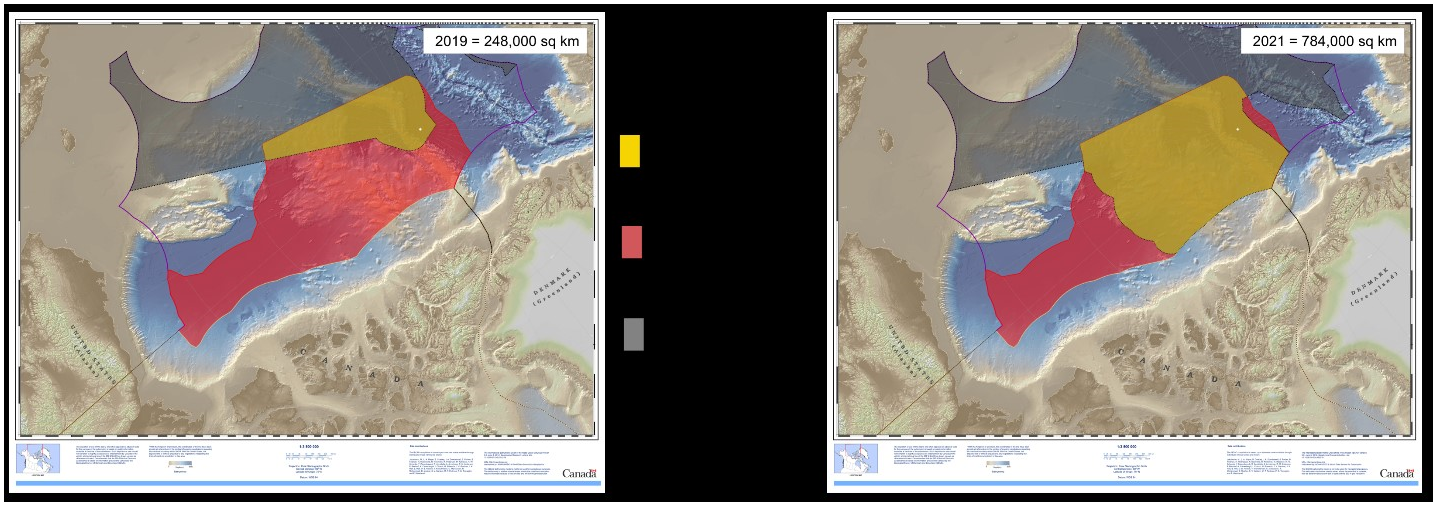

27 Overlap between Canada’s 2019 ECS and the Russian Federation’s 2015 ECS (left); overlap between Canada’s 2019 ECS and the Russian Federation’s 2021 ESC (right).