Introduction

International labour migration and mobility became one of the striking characteristics of the “Trente Glorieuses”, the period of unprecedented economic growth and prosperity experienced by most of western Europe during the early decades after World War II. Between 1960 and 1973 alone, labour migration involved more than 30 million people, as foreign workers moved from southern and south-eastern Europe, as well as north African countries, into the core economies of north-western Europe.Footnote 1 Such an enormous movement of population resulted not only in the temporary presence of an extra labour force but also in large-scale immigration into those countries; it also constitutes one of the largest voluntary, peaceful, economically driven migration movements in modern history.Footnote 2

Quite apart from the scale, scope, and consequences of the European migration system of that time and its migration movements, two of its features call for further research. First, after World War I, European states began to assume an unusual role as they not only controlled migration movements across borders but also acted as mediators in the international labour market, which was made up of a growing number of countries bound together by flows of labour migration. In some cases, states restricted themselves to setting up the political and bureaucratic frameworks, while others began to structure those flows more actively. At times, that involved not only the creation of government-run emigration services but also recruitment commissions being sent abroad by government agencies of receiving countries.

The growing involvement of the state in the regulation of migration is in fact a much debated question in migration research,Footnote 3 especially considering the advent of the Westphalian system in the mid-seventeenth century, the conception of the nation state in the nineteenth century, and the dawn of the welfare state during the twentieth century. However, the growing importance of the state as a mediator on international labour markets has not yet received adequate attention.

Second, the role of the state in shaping labour migration also changed at another level. Between World War I and the oil-price shock of the mid-1970s, bilateral agreements between countries became the institutional backbone of labour migration in Europe as people moved from its peripheries to its economic centres. That turned labour migration policies into matters of international politics and international law. Although treaties to regulate migration had spread throughout the world during the nineteenth century, they were concerned mostly with processes of immigration and settlement.Footnote 4 It was only after World War I that governments started to draw up agreements jointly to organize and regulate the temporary transfer of labour between their territories.

Moreover, attempts dating back to the late nineteenth century by a wide circle of actors, including trade unions, internationalists and their societies, socialist movements, and even some governments, to establish internationally recognized social rights and labour standards for workers, including migrants, bore fruit when the International Labour Organization (ILO) was founded in 1919. The new agency immediately began to formulate standards for temporary labour migration. The dissemination of a set of norms to be observed in the regulation of migration combined with an instrument binding governments to those standards through international law – bilateral migration agreements – fundamentally changed the relation of the state towards temporary labour migration. That, therefore, raises questions about the internationalization of migration politics and challenges the so far little-disputed predominance of the nation state and national politics in migration matters throughout the twentieth century.Footnote 5

Bilateral labour agreements, also known as recruitment as well as migration agreements or treaties, have themselves long played only a marginal role in historical migration research.Footnote 6 Lately, however, interest in them has been growing and they have been discussed from a variety of different angles.Footnote 7 Some authors argue, somewhat strangely, that their application was motivated exclusively by foreign policy and diplomatic strategies.Footnote 8 Other researchers, while acknowledging their importance in defending claims of state sovereignty over migration processes,Footnote 9 make a case for their limited economic and political effect in comparison with the significance of migration itself as a potent social and political factor.Footnote 10 In contrast, the function of such agreements as stepping stones on the road to internationalization and multinational institutions has been underscored,Footnote 11 as has the significant contribution, if not pivotal role, of bilateral agreements in the establishment of transnational social rights and the protection of labour migrants.Footnote 12 Finally, the importance has been pointed out of analysing such institutions from above the national or bilateral level in order to appreciate network effects within multipolar structures made up of bilateral links, to unearth their full impact.Footnote 13 That approach draws on the belief that networks play a significant role at a meso level between traditional approaches in international relations research, which conceptualize links between sovereign nation states in hierarchical or anarchical models, and suggests reassessing the state as an actor within that frame of reference.Footnote 14

This article therefore examines modern labour migration to continental western Europe from the time of World War I until the 1970s, and will consider the position of the state as an actor in an international labour market. We shall examine the attempt by European states to extricate themselves from a complex dilemma: faced with their demographic situations, changes in economic as well as social structure, and the advent of what has been called the Fordist system of production and organized labour, none of the leading economies of western Europe was able to sustain economic growth without the inward migration of labour during most of the twentieth century.Footnote 15

While labour mobility between European economies tended to shrink, continental western Europe had had to accept labour immigration from its southern and eastern periphery from the late nineteenth century onward, while trying to exclude labour immigration from territories outside Europe and from colonial possessions before they had been decolonized. When France departed from that model during and after World War I, it set up strict mechanisms to regulate migration flows from its possessions in north Africa to control the presence of north African labour migrants in the metropolis.Footnote 16 That introduced practices for regulating labour movements which had developed in a colonial context to continental Europe, and crudely shaped a model which, although modified, would be widely adopted to regulate international labour migration during the interwar period.

The increase in state involvement in the management of migration was driven as well by protectionist policies towards wages, working conditions, and the social rights of the domestic workforce, and by the conflict between national social security policies and highly mobile foreign workers. The European answer – brewed from those ingredients – took up the idea of state-regulated temporary labour migration based on bilateral agreements inspired not least by various colonial examples and French practice during World War I.Footnote 17 Selective recruitment, the temporary character of labour migration, and the principle of equal treatment of foreign and domestic workers emerged as key elements in correspondence with the ideas of the International Labour Organization, which stated an improvement in the situation of international labour migrants as one of its central aims. The result was an internationally rooted and commonly practised European model of regulated temporary labour migration which promised to solve the key problem of combining protectionism with labour migration while avoiding permanent settlement and immigration. The migration regime to govern the system gained firmer shape during the interwar years and achieved its greatest momentum between the late 1940s and early 1970s.

While its links to colonial experience are obvious, the European model, which introduced state regulation and control while embracing the ILO's attempts to establish improved conditions for migrant workers through equal treatment and assisted migration, was not intended to be generalized beyond the European context. Though a good deal of regulated and temporary extra-European labour migration before World War II took place within the colonial context,Footnote 18 none of the European colonial powers was in the least interested in disseminating the practices developed in Europe to their colonial labour markets. The ILO consequently achieved little in that respect during the interwar years, and it took that organization until well into the 1960s to trigger changes in standards for labour migration beyond Europe.Footnote 19

To analyse how and why the states of Europe became involved in labour migration at an international level during the twentieth century, this article employs a dual model: it will discuss the development of bilateral recruitment agreements as an institution, and their spread as an instrument. Governments acting at a multilateral level in international migration politics will be observed as they created a framework for the governance of labour migration. A look at specific exemplary migration relations based on bilateral recruitment treaties will show what practices ensued between states and how they shaped migration processes. Also, variations in the direct involvement of the state in the international labour market need to be discussed. Finally, interdependencies in the evolution of internationally recognized standards, a system of bilateral treaties, and the state will all be traced in search of their influence on the shape of international labour migration between the 1920s and the 1970s.

The system of labour migration in twentieth-century Europe

To limit the scope of the migration currents and interconnections to be taken into account, currents of labour migration will be considered which meet four criteria. Firstly, migration movements have to be sparked by industrialization or demand originating directly or indirectly in the secondary or tertiary sectors of an economy. In turn, the supply of migrant labour has to stem from backwardness in such a process. Secondly, population movements between peripheral and central zones must predominantly be intended as temporary migration. Thirdly, migration patterns have to be increasingly regulated by an institutional framework, and the fourth criterion will be that the overall migration process has a profound effect on the economies and societies of both the sending and the receiving countries. Given all that, an appropriate point of departure will be a chronological look at the migration system constituted by qualified currents of labour migration starting in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 20

Following that compass, five major movements of transnational labour migration can be identified within western Europe prior to World War I. Emigrants from Italy started to gravitate towards some of the major economies of continental Europe, namely France, Belgium, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Germany.Footnote 21 In addition, Germany saw a steady influx of labour migrants also from those parts of Poland which had been annexed by Russia and Austria.Footnote 22 The north African territories of France – Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia – were attached to the system during World War I,Footnote 23 and Spain and Portugal developed ties to the labour markets of central Europe at the same time.Footnote 24 The interwar years saw the restoration of the Polish state and its incorporation into the international labour market, while newly founded countries and those which gained independence at the time, such as Hungary, Yugoslavia, Romania, and Czechoslovakia, became significant sources of labour for various European economies, before the Cold War excised them from the system after 1945. Among the countries of eastern Europe, Yugoslavia alone managed to revive its labour-market relations with the West in the postwar era.Footnote 25

The international labour market was disrupted by Germany through the occupation of many European countries and their incorporation into the German system of slave, forced, or otherwise recruited labour as part of the German war economy between 1939 and 1945, but the market's reconstruction started as soon as World War II ended.Footnote 26 Traditional migration patterns, such as those between France and Italy, or Belgium and Italy, were the first to thrive again, but in subsequent decades Sweden, Austria, and the Netherlands joined the system on the demand side, although their intra-European labour market relations have earlier roots, namely in the interwar period.Footnote 27 On the other hand, Greece and Turkey were newly integrated as fresh suppliers of labour migrants only during the 1950s and 1960s.Footnote 28 The western European system of labour migration reached its highest density and largest size during the late 1960s, with migration currents peaking between 1967 and 1972.Footnote 29

The state and bilateral labour agreements

Bilateral agreements regulating temporary labour migration

While the number of countries interconnected by currents of labour migration expanded steadily, a specific form of bilateral agreement gained growing importance as a means to regulate the flow of labour between countries within the system.Footnote 30 The idea of bilaterally fixing terms to frame settlement migration between states by using conventions or treaties had proliferated throughout the nineteenth century. In 1904, France and Italy concluded the first of a series of agreements aimed at establishing certain standards, procedures, and protocols in the context of modern labour migration and its consequences for the transfer of funds or claims against national social security systems.Footnote 31 This treaty heralded a new era of bilateral migration agreements, although its form and coverage were not as far-reaching as the agreements that would follow during the interwar years. Nonetheless, it clearly reflected the ideas of social reformers who were trying to protect both migrant workers from exploitation, and domestic workers from the erosion of their social rights which would tend to be the result of the availability of a cheaper and less well protected labour force of foreign, immigrant, workers.Footnote 32 The treaty and its successors must be seen also as early attempts by the emerging welfare state to factor international migration into national social security schemes. To arrive at what would finally become the modern bilateral agreement on labour migration after World War I, two more ingredients were required: the regulation of labour transfer between colonial empires through bilateral agreements,Footnote 33 and the experience of organizing an external labour supply under conditions of total war, which arose between 1914 and 1918.Footnote 34

A new model for bilateral labour migration agreements finally began to appear across Europe in the 1920s. Now, European states began to intervene thoroughly in regulated labour migration in peacetime, and France again took the lead in developing and propagating the new institution.Footnote 35 The labour agreement concluded between France and Poland in 1919 can be rated as the first of this new generation of treaties. It became an internationally accepted standard and provided the nucleus for the subsequent spread of the institution, its main innovation being its regulative range and clear structure. In addition to conditions for the admission as well as the residence of foreign workers and some basic labour standards, the treaty created protocols for the administration of the recruitment and transfer of migrants between labour markets. The agreement in fact set up a new migration channelFootnote 36 alongside spontaneous individual migration: the recruitment of foreign labour, organized or at least regulated by the state, combined with a dual selection of candidates by the representatives or authorized agents of both governments involved.Footnote 37 In fact, access to the new migration channel was withdrawn from individual choice and put instead under state control, direct or indirect.

Furthermore, the process of balancing the demand and supply of labour power was transferred to the labour markets of the countries which were providing migrant workers, because selection according to demand was now executed before the actual migration process began. Along with such far-reaching means of controlling economically motivated migration, the principle of equal treatment of foreign and domestic workers was anchored and codified, so that, at least notionally, Polish migrants could expect the same labour standards as their French co-workers.Footnote 38 The increase in control seemed to work both ways, as stricter rules for immigration meant more reliable – and at times indeed improved – conditions of work and residence abroad.Footnote 39

From early treaties to international standards for regulated labour migration

The formation of this new institution can be traced on two levels. In the multilateral sphere, the International Labour Organization became an important platform on which standards were negotiated, formulated, and promoted between representatives of member states, trade unions, and employer associations,Footnote 40 even if the actual adoption of those standards remained at the discretion of each national government. On the second level, the diffusion of labour standards for migrant workers through bilateral agreements can be observed as it actually happened. The core countries of the European migration system concluded thirteen bilateral labour agreements between 1919 and 1934, and a further eleven treaties expanded the system temporarily towards eastern Europe prior to World War II.Footnote 41 Even Nazi Germany stuck with the common form of labour agreement in an attempt to create some sort of normality within its sphere of influence while installing a system of forced and slave labour: between 1937 and 1943 it signed a total of sixteen labour treaties with allied states or territories.Footnote 42 After 1945 about forty primary and subsequent labour treaties which closely followed the model created by the ILO during the interwar years can be counted within the system, which therefore established firm pathways for labour migration.

When the ILO started to become an effective actor on the international stage in 1919, just weeks after Poland and France had signed their ground-breaking agreement, an organization had been created which for the first time united the three major actors in modern labour markets: state, trade unions, and employer associations.Footnote 43 Activities of the ILO concerning international labour migration can be traced right back to the beginning of its operations.Footnote 44 To that end a special commission was set up to investigate the conditions of international migration with respect to standards for migration processes.

The report it presented in 1921 lists the main areas of maltreatment or discrimination of migrants in general and labour migrants in particular. It reads like a plea for a general reform and regulation of migration policies and procedures.Footnote 45 Indeed, many of the early ILO recommendations – for instance cooperation among the national bureaucracies involved, enhanced control over private agencies, the establishment of fixed protocols for the exchange and distribution of information, the use of standardized employment contracts or government-controlled collective recruitment, and transfer of workers – were eventually to become commonly accepted features of regulated labour migration. The ILO translated its standards into several conventions and recommendations which concerned themselves with labour migration, hoping that a growing number of states would accept them and adjust their national legislation, policies, and administrative practice accordingly.Footnote 46 It took the ILO until 1949 to construct a grid of such standards and sum up its efforts in Convention 97 and Recommendation 86. In becoming the blueprint for regulating temporary labour migration, that Convention and Recommendation together constituted a model bilateral migration treaty which was to be used by European countries from the end of World War II until the tailing off of recruitment in the early 1970s.Footnote 47

Structuring an international labour market

Equally important insights can be gained by reflecting on the international labour market itself as an entity in which one group of economies offered workers, and another group of countries needed additional labour. The result was a network of supply and demand relations that effectively created the migration system. In fact, a growing number of countries entered a transnational labour market either to supply labour or because they were in need of it. Through migration streams and bilateral treaties they became entangled in complex market relations: every country of emigration was connected to several countries of immigration and vice versa, which made countries in the same class competitors either for workers or for jobs.

As international standards negotiated by the ILO proliferated after 1945, it can be assumed that a certain collective pressure built up to include the treatment of labour migrants in the formation of general labour standards. First, common international standards, especially on equal treatment, helped to protect advanced national labour standards, such as sophisticated social security systems or collectively negotiated wages. Failure to comply in effect led either to a loss of competitiveness or an erosion of national standards. Second, the amelioration of labour standards for migrants was important in defining one's position on the international labour market as a bidder for labour power. Hence a clear trend can be observed from before World War II and again after it, indicating that countries entering the system of bilateral labour treaties tended to adopt the ILO's ideas at least partially, or orientated themselves towards the French model. Even Germany, which initially used different forms of bilateral agreement in the 1920s, showed signs of converging with what was to become the mainstream.Footnote 48 None of that implies a total concordance of agreements, rather a convergence of structure and content but with some room for manoeuvre, which gradually led to a wider adoption of certain standards, with every new treaty of the kind making further dissemination more likely.Footnote 49

France, for instance, used the model treaty worked out with Poland to regulate many of its other international labour market relations in the 1920s and 1930s. Countries that concluded such agreements with France, in turn, used the set of conditions put in place by France as the basis for labour market relations with other countries. That pattern became even more noticeable after 1945. In composition and range, most European labour recruitment agreements followed the ILO model more or less strictly. Treaties became more similar in their overall makeup, but discrepancies in detail remained. Beside the macro trend of slow convergence, a third force must be taken into account, which could generate rapid progress in standards in certain sectors of the migration system. That force gathered strength whenever rivalry between the most powerful players became acute: sometimes economies competed for foreign labour on the international labour market, or more precisely for labour from a particular labour market within the system of bilateral migratory links.

Such competitive pressure on a contested labour market where many recruiting countries looked for labour migrants could induce structural changes to the migration system, as indicated by its expansion through the inclusion of Turkey in 1961,Footnote 50 or the German turn towards recruitment in Greece in 1960 and its acquisition of a dominant position there.Footnote 51 Yet most importantly, a third kind of reaction can be identified in the improved competitiveness brought about by improvements in conditions for labour migration and in labour standards through new or modified migration agreements. Each of those decisions had to be made in the political realm, negotiated at the international level as well as codified by bilateral agreements and – at least in part – implemented by one key actor: the state.

The state on the international labour market

On the ground: actors, procedures, and migrant experiences

While we have so far concentrated on the international level and international law, it is also important to discuss the practices of regulated migration which resulted from the changing role beginning to be assumed by governments and their agencies. Though this section will focus on labour-receiving countries, the state agencies of labour-exporting countries will be considered as partners, in order to demonstrate how states with a common macro interest in the transfer of labour but differing micro interests interacted.

Fig. 1 The Spanish Ambassador Marqués de Bolarque and State Secretary Van Scherpenberg of the German Foreign Office sign the recruitment agreement between Spain and Germany, Bonn, 29 March 1960. Photograph: Rolf Unterberg. Bundesarchiv Bildarchiv, Berlin. Used with permission.

A model of state involvement derived from the study of practices at the national and international level both before and after the disruption of 1939–1945 reveals government intervention in all phases of regulated labour migration. In labour-receiving countries the state often collected employers' requests for foreign workers centrally in order to try to match demand first through interregional, but internal, migration. They could then determine whether the immigration of foreign workers was economically feasible and subsequently approve the recruitment of required contingents of migrant workers.Footnote 52

Bilateral treaties then obliged governments to carry out recruitment procedures themselves or authorize private or semi-private agencies to do so, and to monitor their operations closely. Such procedures, which were carried out in liaison with partner organizations from the labour-sending side, included dispatching recruitment commissions, medically examining potential migrant workers en masse, as well as testing their professional qualifications to determine their aptitude. Selected candidates were usually transported together by train from central recruitment centres to distribution points in the receiving country and from there taken to their future employers. Once in their place of destination, the conventional mechanisms to control the presence and mobility of foreigners usually took over.

That level of involvement fundamentally changed the position of the state or, in other words, altered its migration regime. To the state, controlling migration was no longer limited to keeping foreigners out nor to controlling their movements or even presence, but also about getting the right ones in, in certain numbers at a certain time and for certain periods. Moreover, recruiting those migrant workers could become a competitive business which involved much more than opening or closing the gates.Footnote 53

Within Europe, the presence of government-run as well as private or semi-private but government-licensed recruitment agencies on the labour markets of emigration countries can be traced back to the early twentieth century. Prussia, for instance, had set up the Deutsche Feldarbeiterzentrale, which worked under the auspices of the Chambers of Agriculture and the Prussian Ministry for Agriculture from 1905 to hire agricultural workers from eastern Europe.Footnote 54 A semi-official organization, it managed labour recruitment throughout World War I and during the interwar years before the state-run labour administration, which had come into being in 1927, took over recruitment operations directly in 1935.Footnote 55 Labour recruitment by the state labour administration became an integral part of the Nazi system of forced labour during World War II.Footnote 56 In the 1950s the agency (by then the Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsvermittlung und Arbeitslosenversicherung) managed to reclaim its monopoly of labour recruitment abroad when Germany returned to the international labour market and organized recruitment campaigns in almost every country with which Germany concluded bilateral labour agreements.Footnote 57

Other countries went down a similar path. During World War I, France, for instance, had set up government-run recruitment services as well as licensing private organizations to attract workers from Spain as well as other allied countries, and from its overseas territories.Footnote 58 Nonetheless, when France started to build up a vast network of bilateral migration agreements in the 1920s to provide an adequate labour supply for postwar reconstruction, recruitment operations abroad were passed into the hands of a private company, the Société générale d'immigration, established by employer associations in 1924. Only those parts of the migration process which had to be managed within French territory were kept under direct state control.Footnote 59

Although the idea of creating a national Office public d'immigration gained popularity during the 1930s, it took until after World War II before a government agency gained control over the management of all stages of the migration process, when the Office national d'immigration (ONI) came into being in 1946.Footnote 60 The French government insisted on setting up offices in most of the European countries with which it had concluded bilateral treaties, but the ONI proved so bureaucratic and inefficient that private recruitment and individual immigration soon became commonly accepted. In fact, it was even promoted by the French government through its liberal practice of regularizing irregular migrants after they had found jobs.Footnote 61

In contrast to France and Germany, smaller countries too among the labour-receiving economies of Europe experienced growing involvement of the state after World War II, but they relied on private or semi-private organizations to recruit workers abroad. Belgium, which initially needed foreign workers predominantly for its mining industries, relied on the Fédération des Associations Charbonnières, an association of mining companies, during almost the entire period. The federation had started to recruit workers privately in Italy in 1922–1923 and soon became the agency authorized by the Belgian government to conduct recruitment operations abroad, which it carried on doing until the early 1970s.Footnote 62 Luxembourg for its part tried to switch recruitment operations from the private sector to a government agency after World War II, and sent a recruitment commission from its national labour administration to Italy, though it soon returned to allowing private-sector recruitment within the framework of bilateral agreements, because the intended process of state-run recruitment proved too slow to fulfil employers’ requests for foreign workers.Footnote 63 Similarly, the Netherlands used a mixed system of labour recruitment through official posts and private-sector agencies in various countries when it built up its network of bilateral agreements during the 1960s.Footnote 64 Other attempts to increase direct government involvement in the recruitment process eventually leading to heavy reliance on monitored private-sector recruitment can be discovered in Austria,Footnote 65 Sweden,Footnote 66 and Switzerland.Footnote 67

Such observations can be put into perspective with regard to the strategic purpose of government-run recruitment and regulation of migration between two countries. Generally speaking, four types of migration channelsFootnote 68 can be distinguished, between two labour markets, which relate to large-scale migration of low-skilled workers in the European context. The first is direct recruitment of workers specified only by certain characteristics such as age, sex, health, and qualifications. The second is the individual recruitment of persons known by name to recruitment agencies or employers. A third channel encompasses the unassisted individual migration of workers who have already found a job abroad or are allowed to search for one during a fixed period. Fourthly, irregular migration with subsequent illegal presence and employment, or its regularization, constitutes a specific migration channel as well.Footnote 69

Most countries tried not only to coordinate migration and/or recruitment from different sources but also to operate migration channels in parallel to cater to their needs for labour market related immigration. Governments intending to encourage labour immigration while maintaining a certain degree of control over it often relied on government-run or government-assisted recruitment to begin with, in order to initiate the process. In case of a lasting demand for migrant workers, more liberal countries often chose to withdraw temporarily from an active role by granting greater leeway to private recruitment as well as to individual migration – regular or irregular – once a migration movement had gained momentum. Countries preferring more restrictive migration policies had the option of maintaining a higher degree of official involvement but had to build up an effective recruitment apparatus in order to meet demand for an external labour supply efficiently. In any case, maintaining an official recruitment operation preserved the opportunity to close or restrict alternative channels quickly, and limit labour migration to direct recruitment as soon as demand began to dwindle. That way, migration currents could be cut off quickly, as happened in 1967 and 1973 in Germany as well as in most other countries of continental western Europe.Footnote 70

All labour-sending countries at the European periphery basically shared similar expectations, namely to export unemployment temporarily, gain foreign currency by remittances as well as qualified re-migrants, and factored those into their economic plans.Footnote 71 Some of them had already been countries of emigration long before temporary labour migration to western Europe became a major current within their emigration movements. Hence, the governments of Italy, Portugal, or Spain could draw on their experience in the management of migration processes and used their emigration services – in some cases long established – to put their migration regimes into action.Footnote 72 Other countries, such as Turkey, Greece, and Yugoslavia, which lacked such a background, entrusted their labour administration with the task of guiding the process according to their political, economic, and social objectives.Footnote 73

Given the structure of regulated labour migration set up by bilateral agreements, agencies of emigration countries largely worked on their own territory as they participated in mobilizing and selecting potential migrants. Two main branches of their activities were tied to the international arena, since many of the bilateral agreements allowed officials from labour-sending countries to monitor the treatment of their compatriots working abroad, to set up agencies intended to provide certain social services, and to monitor the migration process. They were intended not only to protect a nation's own citizens but, in many cases, it was hoped that cultural and social links could be kept alive in order to foster labour migration that would turn out to be temporary rather than permanent.Footnote 74

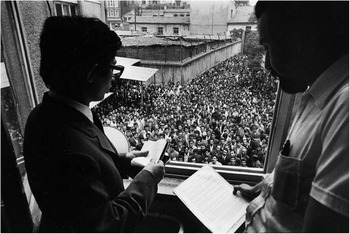

Fig. 2 German officials looking down at potential labour migrants gathered in the courtyard of the German recruitment post in Istanbul, 1972. Photograph: Jean Mohr. DomiD Archive, Cologne. Used with permission.

Other than that, the influence of the state became most apparent in the selective mobilization of migrant workers. In Spain, for instance, the Instituto Español de Emigración, founded in 1956, tried to force labour-recruiting countries to concentrate their efforts on Spain's underdeveloped regions. It went so far as to assign certain territories to the recruitment campaigns of France and Germany, and aimed to restrict all other forms of labour emigration other than official recruitment controlled by both countries involved.Footnote 75 The Portuguese Junta da Emigração strove to implement a similar policy of strict control in an attempt to allocate migration opportunities in pursuance of Portugal's own economic and social policies.Footnote 76 That certainly implied quite restrictive migration regimes and forced willing migrants to accept a rather limited set of choices once they had decided to participate in the official recruitment schemes.Footnote 77 Such attempts to tailor temporary labour migration to fit social policies and economic planning actually left an imprint on migration currents which often bore distinct geographical, demographic, and gender characteristics as far as the origin of migrants was concerned.Footnote 78

Yugoslavia did not establish a designated migration service when it integrated itself into the western European migration system, but it did arrange its labour administration to link up with foreign recruiting services. Probably mindful of German labour recruitment during World War II, it successfully managed to hold its foreign partners at bay.Footnote 79 When a bilateral labour agreement came into being in 1968, the German recruitment commission was not allowed to work as an independent body but had to be integrated into the Yugoslavian labour administration and was required to transfer control over the recruitment process almost entirely to Yugoslavian hands.Footnote 80 Of course, in all three examples many migrants were simply driven into irregular emigration or tried to gain access to alternative migration channels. Such stratagems were even implicitly acknowledged by many labour-sending countries, which recognized that official emigration agencies often worked with a great lack of efficiency and seldom met the intended emigration rates, while anyway the by-passing by emigrants of official recruitment could not be prevented.Footnote 81

Labour-sending countries were therefore effectively obliged to manoeuvre between two extremes. Granting potential migrants liberal access to all principal migration channels maximized the magnitude of migration and thus its relieving effect on their own social problems as well as on the reflux of remittances. The downside of the strategy lay in the uncontrolled drain of qualified workers who, of course, were the most sought after by recruiting agencies from the “other side”. In contrast, maintaining a high degree of control by granting access to the recruitment channel only to preselected candidates seemed to prevent undesired emigration but usually drove people into illegal emigration, and could cause countries wishing to import labour to turn towards more liberal partners on the international labour market.Footnote 82

Such observations indicate the significance of relations between state agencies and other actors in labour-sending and labour-receiving countries alike. Designated as partners in the regulation of labour migration by bilateral treaties and charged with monitoring and organizing the process, they shared an overall interest in the temporary transfer of migrant workers, although actually they largely disagreed on whom to admit. As national business cycles in Europe tended to synchronize themselves after World War II, labour-receiving countries looked for foreign workers during economic upswings when the internal demand for workers in the labour-sending countries also began to surge. During downswings, however, when sending countries strove to rely on emigration to relieve their domestic labour markets, receiving countries tried to limit the influx of migrants. By the same token, sending countries were interested in sending abroad those sections of their workforce with low qualifications as well as unemployed workers and wanted to keep qualified workers to themselves. Of course qualified migrants enjoyed by far the best chance of being admitted to the labour market of a recruiting country and then being allowed to stay there for a prolonged period. In fact, during recruitment operations, the emigration services of labour-sending countries tended to offer employment candidates who would fit their own agenda, while in turn the recruitment agencies of the receiving countries were in the market for migrants with their preferred profile.

Results were mixed. Germany and Portugal, for instance, shared a common interest in tightly controlled labour migration and limited family reunion. Both countries agreed to limit the process largely to state-controlled recruitment. At the same time, it emerged that a large proportion of labour migrants from Portugal to France simply went to avoid official recruitment, because geographical proximity facilitated individual migration, which was often irregular. Likewise, Spain tried to implement a controlled recruitment and migration process, while France made no effort to enforce the ONI's recruitment scheme in order to maximize its gain of Spanish workers.Footnote 83

In other cases, however, organizations entrusted with the management of labour migration in labour-sending countries never gained proper control of the process in the first place. In Turkey, the national labour administration was simply overrun by workers wanting to register for emigration, and only very few of its programmes designed to create a strategic structure for migration flows actually succeeded.Footnote 84 Greece fared even worse, as domestic political actors neither agreed on an emigration policy nor succeeded in setting up an organization to manage the process. Consequently Germany, which turned out to be the most important destination for Greek labour migration during the 1960s, enjoyed a great deal of leeway in which it tailored the extraction of migrant workers to its own needs.Footnote 85

With respect to Greece, Turkey, Spain, and Portugal, as well as Yugoslavia, labour recruitment also gained a political dimension, because the first four countries were, at least for a number of years, authoritarian regimes or actual dictatorships, and the fifth was regarded as a socialist country and almost part of the Eastern bloc. Framed by the conflict between the West and the East, political questions seldom appeared to be at issue when bilateral treaties were negotiated, nor while recruitment operations ran in close cooperation with the institutions of Western dictatorships. In contrast, labour migrants from Yugoslavia who travelled to Germany were at times seen through the ideological prism of the Cold War as a fifth column, poised to strike.Footnote 86 In fact Yugoslavia – like some other rather authoritarian regimes – tried to implement a degree of control over its expatriates to ensure their political loyalty during a migration process which was largely perceived as a temporary phenomenon.Footnote 87

How then did the expansion of state interference with labour migration affect the migrants themselves and shape their experience? Regulated labour migration as set up by bilateral agreements subjected migrants to a highly organized and controlled migration regime which possessed a Janus-faced character. Direct contact with recruitment services or migration officials often left migrants with degrading experiences. They were subjected to processes of selection by agencies of their own country as well as those of potential destination countries. Medical examinations were organized rather like musterings for military service and were carried out with little thought for privacy or discretion.

Many receiving and sending countries implemented procedures to check the political backgrounds of potential migrants. Sending countries typically tried to prevent evasion of compulsory military service, and the authoritarian regimes attempted to control or restrict the movements of political opponents. They faced a more or less permanent dilemma over whether to allow opponents to leave, thereby making their job of ruling easier at home, or to keep them at home in a bid to control their activities. Following that logic, access to regulated labour migration was to be granted first and foremost to loyal subjects.Footnote 88

Receiving countries for their part tried to prevent criminals or “radicals” from entering disguised as labour migrants. Such fears mainly had to do with the “threat” of communist intruders, but in practice many attempts to monitor migration streams closely were doomed, given their sheer magnitude and the inability of security organizations to keep pace with them. Nonetheless, the entanglements of politically and economically driven migration during the recruitment phase as well as the role of oppression, political conflict, and the Cold War in general remain fields deserving renewed research efforts.Footnote 89

Finally, organized collective transport – mostly by rail – to host countries, to say nothing of the bureaucratic procedures required to register for and then obtain a work permit, often left bitter memories. Moreover, the experience of being rejected from recruitment, or of undertaking to migrate through other channels, was shattering for individuals. Even well-intended efforts to support migrants – for instance through brochures providing information about the host country – sometimes contributed to the asymmetries between expectations and the realities of migration. Informing potential migrants about what they could expect and helping them to cope with their journey and residence were in fact integral parts of regulated and assisted migration, and were anchored in almost every bilateral agreement which followed the ILO model. At the same time, advertising potential host countries as attractive destinations for well-qualified migrants was the cornerstone of what recruitment services did, and they often created expectations which would subsequently be sharply contrasted by the harsh realities of living in western Europe as a temporarily admitted labour migrant.Footnote 90

The ambiguous character of regulated labour migration also shaped the experience of female migrants. According to the ILO standards, assisted migration, the promise of equal treatment, and special initiatives to protect female migrants should have reduced discrimination.Footnote 91 However, the realities of managed migration often proved not to fulfil those promises. The migration regime installed by bilateral treaties and government-run recruitment actually implemented a gender bias: while female migrants became a significant group involved in the recruitment scheme, the system failed to provide for conditions equal to those offered to male migrants in many places. Loopholes in the system allowing discrimination against women rather created incentives which reinforced structural discrimination.

While the emigration of single women often became a contested issue in the countries of emigration in southern Europe, female migrant workers quickly became much sought after by recruitment agencies.Footnote 92 Since it was easy for employers in the countries receiving immigrants to avoid paying equal wages to women, the recruitment process was characterized by an extremely high demand for female migrants, especially after World War II when collective bargaining and rising wages for domestic male workers drove up labour costs.Footnote 93 As a consequence, during the 1960s German employers who asked recruitment agencies to provide female workers sometimes had to wait several months before the first applicants arrived for work. In an almost frantic hunt for female workers, German recruitment officials, for example, hectically forwarded such requests from country to country trying to find suitable candidates quickly.Footnote 94

Among the many degrading experiences of women caught up in the recruitment process, the handling of pregnancy soon became a major concern for employers and recruitment officials alike. For instance, German employers reserved the right to refuse work to female migrants who arrived pregnant, and sometimes denied pregnant migrant workers appropriate health and safety measures while at work. As late as 1971, a company from Aachen forced female migrant workers to give up newborn babies for adoption under the threat of evicting mother and child from company housing.Footnote 95 Despite such questionable and frankly inhumane practices, female migrant workers made up an increasingly large proportion of the people moving through the European migration system after 1945.

When recruitment came to an end in the early 1970s, women made up about 25 per cent of all migrants who had passed through that migration channel. Many had managed to turn into agents of change and used their increased mobility to move towards self-determination.Footnote 96 At another level, women entered the migration process through family reunion, which also turned out to be contested ground. Throughout the interwar years, and especially after World War II, countries recruiting labour could choose either to reject family reunion to minimize the settlement resulting from temporary labour immigration, or to welcome families in order to draw more migrant workers into their labour markets. Countries of emigration had the opposite choice, between facilitating family emigration and hampering it. One important reason for the latter was to secure the reflux of remittances by keeping the families of migrant workers at home, which was what Portugal tried to do. On the other side, restrictive migration policies of immigration countries regarding female migrant workers and female migration within the context of family reunion often put them in a most difficult position – as has been shown in the case of the Netherlands since 1945, for instance.Footnote 97

Some important features of regulated migration tend to be concealed behind such experiences and memories, which naturally dominate the image and interpretation of labour recruitment. In fact, millions of male as well as female labour migrants went through a thoroughly organized process which attenuated many of the most notorious dangers of international labour migration, reduced insecurity, and lowered migration barriers. Regulated migration based on bilateral treaties provided standard work contracts in the migrants’ own languages and – at least nominally – secured equal treatment in working conditions and social security. Migrants had jobs waiting for them before even setting off and were guided from their points of departure to their new workplaces, where housing had to be provided and the cost of travel was, at least in part, lifted from their shoulders.

Medical and professional examinations could even be interpreted as measures designed to make sure that anybody who began a journey had a good chance of fulfilling their contract, which was in the interests of migrants themselves as much as it was of the other parties involved. Of course, rejection was disappointing; but whoever made it through the gates to the channels of regulated migration was better protected and cared for than generations of labour migrants who had gone before.Footnote 98 It certainly did not prevent exploitation, nor did it shield migrants from discrimination and racism, but it marked an advance when compared with circumstances in the periods prior to the implementation of bilateral migration agreements.

Fig. 3 Italian labour migrants begin their return journey at Cologne main station, 21 December 1973. Photograph: Ludwig Wegmann. Bundesarchiv Bildarchiv, Berlin. Used with permission.

In addition, the aspiration of governments to extend their control over international labour migration by no means left the migrants themselves without agency. Alongside their ingenuity in gaining access to alternative migration channels, migrants were well aware of the various alternative destinations that were open to them.Footnote 99 As the system of bilateral agreements expanded and more and more recruitment services became established in the urban centres of labour-sending countries, competition among them became a factor of which migrants could take advantage.Footnote 100

In Milan, for example, recruiters from France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Luxembourg were already present when Germany opened its recruitment post in 1955–1956, and their Austrian and Dutch colleagues entered the arena during the 1960s. One consequence of the situation was fierce competition among the representatives of those countries for Italian migrants. Recruitment services tried to grasp as much as they could of the market for workers by aggressive advertising campaigns and by making improvements in the conditions they offered. On the opposite side, Italians exploited their options cleverly by registering with several recruitment campaigns simultaneously, so that if they passed more than one examination they could choose the most attractive offer.Footnote 101

There is similar evidence from north Africa that Moroccan migrants balanced registering for a job in the Netherlands, where, in the event of their being laid off, unemployment benefits became available to them more quickly, against going to Germany, which offered higher wages but where it was harder to qualify for unemployment benefits.Footnote 102 Finally, government officials as well as agents of private companies conducting recruitment operations were immune neither to bribes nor cheating, and buying one's way through the examinations of the domestic emigration services or on to lists of accepted candidates became not only a sport but practically a branch of organized crime in some countries of emigration.Footnote 103

The impact of competition for migrant labour

The effects of competition and choice as they become apparent at the micro level shed light on a neglected aspect of labour migration. It is usually assumed – and in many cases it was true – that because migrants were in competition for jobs they were easy to exploit since they enjoyed little protection. However, the institutionalization of regulated labour migration and the almost continuously growing demand for migrant workers in western Europe throughout most of the twentieth century sometimes turned the wheel of fortune in their favour. Besides its effect of expanding the options open to migrants and their use of them, the impact of competition can be traced through the history of bilateral treaties. Three examples will be used in this section to illustrate that process, one selected from the interwar years, two from after 1945.

When France and Poland began to organize large-scale labour migration in 1919, which resulted in the immigration of more than half a million Poles to France during the 1920s, Germany's position in the Polish labour market was severely weakened. A quasi-monopoly was lost, and although that did not prove too harmful during the crisis-shaken early 1920s, it was to become a problem when the demand for Polish labour migrants in Germany rose again during the second half of the decade. Simultaneously, the advantageousness of the Polish position, with what had been a virtually unlimited demand for migrant workers in France, was diminished in the late 1920s by a tightening of French migration policies. Consequently, when Poland and Germany concluded their first labour recruitment agreement in 1927 the treaty bore signs of both those developments.

Germany was neither ready to depart fully from its own tradition of labour agreements nor openly to adopt the French model of bilateral treaties, but it had to make certain concessions. Poland became entitled to send workers to Germany within a quota framework and mandatory model contracts negotiated yearly, which enhanced the equality of treatment. In turn, the agreement entitled Germany – for the first time – to send official agents of its own labour administration into Poland to conduct recruitment operations. The recruitment itself had to be carried out under the strict control of Polish governmental agencies, which were allowed to determine recruitment areas and influence the selection of candidates. Also, protocols for a periodic evaluation of regulations and practices were introduced, which mimicked the Franco-Polish agreements. Interestingly, Poland used its amended labour relations with Germany to start fresh negotiations with France on a further enhancement of migration standards, until finally even the French association of agriculturalists pleaded for a new agreement with Poland, to be modelled on the German treaty. Its operatives mistakenly believed that Germany had granted Poland even better conditions than France had.Footnote 104

A second example concerns the actions of Belgium and France in the Italian labour market after 1945. Both countries were short of miners in the early postwar years and turned to Italy as the classic source for migrant workers. France put forward its first migration agreement in February 1946, but established a bureaucratic and frustrating recruitment procedure without explicitly granting equality of treatment. On top of that, a complicated system for transferring funds back to Italy – essentially allowing for the shipment only of goods purchased in France – lessened the attractiveness of France as a migration destination. Only four months later, Belgium entered the arena with its own migration accord. It defined detailed migration and labour standards – though not total equality of treatment – and allowed for the swift transfer of savings from Belgium to Italy.

France countered in November 1946 with a novel labour agreement with Italy which made recruitment easier and promised a lump sum for Italian workers as soon as they crossed the French border. Belgium in turn improved its position on the Italian labour market in February 1948. The Fédération des Associations Charbonnières, which conducted recruitment in Italy, presented a model contract for Italian miners that decisively strengthened the equality of treatment and smoothed their path to permanent settlement in Belgium. France relied on its two most powerful levers to regain the lead. In March of the same year, it signed an agreement with Italy on social security, which established equality of treatment. In 1951, a new migration accord between Italy and France followed, marking the transition from the ad hoc agreements concluded in the late 1940s to a full-scale international treaty modelled on the example given by the ILO conventions. The bonus for Italian miners was raised significantly, as it was for other workers.

But while France continued to upgrade migration conditions for Italians in the 1950s, the competition in Italy had already begun to widen further with the arrival of yet more recruitment commissions sent from western Europe. The accumulating pressure of a rising demand on the Italian labour market finally proved to be a strong incentive for labour-importing countries not only to improve the conditions they offered but also to expand the range of their recruitment activities to new foreign labour markets.Footnote 105

That leads to the third example demonstrating the effects of growing competition. When Germany turned to Turkey as a source of labour power in 1961 it became the first European nation to employ labourers from the Turkish labour market. From that position, Germany could push through a recruitment agreement, which installed a migration protocol of inferior quality when compared to the standards established for labour migration to Germany from other countries.

Not only did the Germans initially use an exchange of notes instead of a bilateral agreement, and thus a less binding diplomatic channel, to seal the agreement, they also severely limited the period of residence for Turkish workers in Germany. Exceptional amounts of leeway were given to German recruiters in the selection of candidates, and for the first time criteria were established which led to the automatic exclusion of a sub-group of potential migrants. On top of that, the agreement omitted family reunion entirely, which was unprecedented in German agreements after 1945. Three years later, the situation in Turkey changed fundamentally when Austria, the Netherlands, and Belgium entered the market and established their own migration agreements in 1964. The three treaties closely followed examples set by other labour agreements involving the three labour-importing countries and, in contrast to the German case, showed no significant departures from agreements the Netherlands and Belgium had concluded a little earlier with Spain.

However, by no means did that rule out differences between the different agreements. Belgium, for instance, tended to grant more liberal standards of migration control than did the Netherlands. Indeed, the Dutch often suffered severe disadvantages when competing in foreign labour markets as a consequence of the strict regulation of migration and the inferior options for migrants arriving on the Dutch labour market which resulted from it.Footnote 106 Germany reacted at the end of 1964. A new draft of the migration agreement was prepared which ruled out the most painful grievances. Turkey was allowed to send its own personnel for social care and counselling to Germany, and a special commission was set up to conduct an annual evaluation of the migration process. Both features had become internationally accepted standards by that time, and the German-Turkish agreement of 1961 is one of the few examples to ignore them. More importantly, the Germans dropped from their work permits for Turkish workers in Germany the limitation which had restricted Turks to a maximum of two one-year work periods.

Maintaining such discrimination against Turkish migrants to the German labour market would have been possible only at the price of diminishing the influx of labour migrants from Turkey, given the options that had opened up for them in the mid-1960s. As competition in Turkey tended to increase when France and Sweden started recruiting workers there in 1965 and 1967 respectively, the trend to more liberal migration agreements continued. The French and Swedish agreements proved to grant better conditions to Turkish migrants, putting pressure on Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands to rethink their regulations and to improve labour immigration from Turkey, either formally or informally.Footnote 107

Conclusion

This article has traced the changing role of nation states in an international labour market on two levels, by looking first at bilateral and multilateral international politics and then at the practice of regulating the migration process itself. The first section has shown that from the interwar period onward, rather restrictive paradigms in migration politics could be followed through only by extending the direct and indirect involvement of states in the proactive management of migration and the recruitment of migrants. In that respect, taking over the mobilization of migrants can certainly be interpreted as an extension of control too. Together with the second major current in the arena – the implementation of international labour and migration standards – the outcome, however, is somewhat surprising.

Extending the range of nation states as mediators on the international labour market of Europe required treaties which had to obey international law. The resulting bilateral migration agreements allowed states wishing to establish migration relations to fix terms on the one hand, but then converged towards an internationalized model which bound them to a set of international standards on the other. Those standards were promoted by the ILO, an organization in which nation states cooperated multilaterally as well as with potent third parties, namely trade unions and employer associations. In the end, attempts to extend control led nation states to an internationalization of migration policies, which created networks of structurally standardized bilateral relations between a set of partners. That in turn to a certain degree limited their sovereignty over migration processes and even national migration policies.

On the practical side of migration management, the process required nation states to take over a whole array of new responsibilities. Bureaucracies to control foreigners within national borders were complemented by organizations which enlisted those foreigners abroad through selective recruitment – which often included advertising one's own country as a favourable destination to attract desired workers. Such organizations might be state-run or state-licensed and usually cooperated with their counterparts from the labour-sending countries. Both sides shared a common agenda but competed fiercely to steer the whole process to maximize their specific interests. Such findings can be given context from two perspectives. At the institutional or organizational level, almost every country which became part of the European system of labour migration went down a path of growing direct state involvement, stretching from setting up and operating recruitment posts to orchestrating migration currents through various migration channels as well as from a growing range of partners. Empirical examination of the resulting cooperation of complementary organizations has revealed a great variety of models and degrees of success. The resulting framework can be seen as a transition from predominantly national migration regimes to hybrid ones in which no single nation state could entirely govern migration processes either originating from or targeting its territory.

In that respect, the ILO's struggle to embed standards for the regulation of labour migration must be rated highly not only as a major effort to improve labour and migration standards but also as bringing about seminal changes concerning the management of international migration within the European context. The implementation of such standards within the European system, however, has been shown to rest upon the interaction of several forces beyond the sole command of the ILO or individual countries.

Undoubtedly, the steady spread of a set of rules pursued by the ILO actually contributed to the international convergence of labour migration standards. Although the process slowly gained pace and even significantly changed national politics at times, national paradigms of migration politics were never entirely overruled but always imprinted their character on the way individual states acted within the system. That became visible also in the refusal, well into the 1960s, to extend the principles increasingly applied to regulate temporary labour migration within Europe to include colonial labour markets, and to convert the migration standards defined by the ILO into globally enforced and applied norms. The interplay of the experience of European states as mediators on colonial labour markets, the development of regulated labour migration in Europe, and the development of standards for labour migration in the extra-European world, which is to say the study of migration regimes alongside migration systems, deserve renewed attention.

The significance of the European framing conditions between the 1920s and the 1970s in shaping the combination of state-run recruitment, managed migration, and equality of treatment became obvious when a long-term recession struck the economies of Western Europe and the importance of labour migration dwindled in the face of rising domestic unemployment. This fundamentally changed the situation as soon as the “economic miracle” ended in the early 1970s and the pressure of supply and demand on the international labour market shifted, so that the bargaining position of migrants and sending states became weaker. After recruitment finished, most channels for labour migration were closed or severely narrowed; bilateral agreements for the recruitment of unqualified or lowly qualified migrants played thenceforward only a marginal role. Europe instead embarked on internal labour mobility and began to seal off its borders to immigration in general.Footnote 108 The diminished importance of bilateral migration treaties after the recruitment of “guest workers”Footnote 109 in the European context clearly reflects this seminal turn.

While bilateral labour agreements still play a considerable role as an instrument to regulate temporary labour migration in the non-European world, within Europe they have begun to serve other purposes, for the most part. Although in recent times fears about future demographic development and its consequences for the labour market in some European countries – among them Germany – have stirred up renewed interest in temporary labour migration programmes, bilateral migration treaties have been used since the 1980s predominantly as a tool to manage migration within the context of EU expansion. At the same time, they have become an instrument to fend off refugee migration from Africa and Asia towards Europe and its southern member states.Footnote 110 It could indeed be argued that despite the renewed and even growing importance of temporary work programmes the degraded bargaining position of low-skilled migrant workers on international labour markets has not only ended the international upward convergence of migration standards for temporary workers but also dramatically eroded conditions offered to them by many of their destination countries.Footnote 111

Nonetheless, the remarkable trend during the heyday of the state-run recruitment of temporary labour in western Europe, especially between 1945 and 1973–1974, is worth noting. In an arena framed by national politics and international standards, competition, which is usually expected to work in favour of those countries offering work to migrants, could actually induce a significant shift in the division of bargaining power from which migrants and labour-sending countries benefited. That observation on the institutional level neither rules out nor denies the de facto existence of double standards and discrimination against migrant workers.

Yet their experiences while passing through a regulated migration process which brought them in contact both with their own governments and the governments of their destination country with unprecedented intensity has to be interpreted carefully. The many bitter memories migrants of the “guest worker” period bear with them have to be weighed against the improvement in security and rights brought about by assisted migration during the interwar years and the “Trente Glorieuses” as compared to all previous models. The exchange of individual freedom against such improvements, which resulted in an extension of state control, certainly was a critical price which had to be paid. In the end the strategy employed by many nation states to extend control over migration by turning themselves into key mediators on the international labour market turned out to be at least partially a self-delusion, not only because migrants proved to be tremendously ingenious in reclaiming agency, but also because the idea proved illusory of preventing permanent immigration and settlement by keeping labour migration entirely temporary and controlled. That illusion lured many countries into a self-image as nations of non-immigration, and so postponed policies of integration for far too long.