Introduction

The landscape of the southern mounds of Ur carries a unique ability to narrate the history of the region. Though the encrusted soil may seem grey and monotonous, the monumental remains and deep wadis littered with artefacts speak volumes about the city's long history.Footnote 1 When the sun hits the ground just right, it almost looks like sand, reminding us that the site was originally built along the river and was a grand urban centre, rather than an empty desert. The great mounds of dirt, pottery, and broken objects remind us of the masses of soil cleared during C. L. Woolley's twelve seasons of excavation on the site (Woolley Reference Woolley1954, Reference Woolley1973). The bullet holes riddling the structures’ renovated façades attest to the conflicts of the last three decades (Al-Hamdani Reference Al-Hamdani, Stone and Bajjaly2008b; Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Raheed, Clarke, Al-Hamdani, Stone, Van Ess, Collins and Ali2008: 7–9).

The material changes to the site, in a way, reflect the social, economic, and political transformations of the region; these transformations, for a time, created a rift between local and foreign archaeological teams and practices. This article presents one account of how the challenges of this schism have been addressed through a collaborative training programme. To contextualise the current state of archaeology in the region, we first give a brief overview of past deterrents to collaboration between Iraqis and foreigners within the discipline. Next, we explore the merits and challenges faced during the collaborative training programme run as part of the 2017 season at Ur. Although the bulk of this article focuses on the work at Ur, we also highlight the importance of rebuilding collaborative links and indicate key initiatives at other sites that are working to present pathways to co-creation of such links. We recognise that the collaborative training programme at Ur is not unique within the region, and it is important to place it within a wider framework of parallel initiatives. Finally, we present the future directions of work by those involved at Ur and the broader changes we would like to see in the field. For a map of all the sites mentioned in this article, see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Map of archaeological sites mentioned in the article

Archaeology in crisis: Past hindrances to the study of archaeology in southern Iraq

It is only relatively recently that foreign archaeological teams have returned to the south of Iraq. While the Kurdistan Region of Iraq went through a veritable “explosion of archaeological research” (Ur Reference Ur2017: 176) since the formal US withdrawal from Iraq in 2011, south Iraq was, at first, slower to draw in foreign interest. Central to this disparity was the perceived instability of central Iraq in comparison to its north-eastern Kurdish counterpart. Under the rule of Saddam, the populations of the south were subject to sectarian rule. Saddam claimed all of Mesopotamian ancient history, particularly the Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian states and empires, as the predecessors of his own self-aggrandising regime. This practice not only elided large swathes of history and change, but it also alienated many people from their own regional histories, forming a divide between state-sanctioned and local understandings of Iraqi identity. During the instability following the Iran-Iraq War, a segment of the population disenfranchised by these narratives revolted, a revolution that in the south became a proxy extension of the Iran-Iraq War (Al-Hakim Reference Al-Hakim1994; Harby Reference Harby2015; Hiltermann Reference Hiltermann1993). A brutal battle for control was waged, in which thousands died and many more were displaced from their homes. One of the results of this conflict was the draining of the marshes and the relocation of their inhabitants (Jawad Reference Jawad2021). During the war, the topography of the marshes had made them a haven for those seeking to avoid the long arm of the state. However, in the war's aftermath, those afflicted by the draining were mostly civilians not previously engaged in the revolt.Footnote 2 This had tragic results for the local economy and ecology, and the situation was destabilised further during the subsequent foreign military occupation of the region.

Many archaeologists working in the region today still carry memories of the archaeological optimism in the late 1970s that was dashed by the first Gulf War in the early 1990s.Footnote 3 The sanctions after this war forbade foreign archaeologists from working in the region and made it difficult for local scholars to fund on-site research or maintenance, leaving many sites unguarded and vulnerable, opening them up to looting and decay.Footnote 4 In addition to the deterrents of Saddamist scare tactics and foreign occupation primarily by American troops, the threat of terrorism cast a dark cloud of uncertainty over the safety of the region, creating a barrier to many teams trying to secure approval from their own institutions and governments for research. However, for many archaeologists, these risks paled in comparison to the significance of continuing work in this region. The geopolitically contested areas are of great archaeological significance, and the ancient settlements of southern Iraq are central to our understanding of civilisational transformations, providing a stage for state formation, urban origins, and the development of writing.

The issues run deeper than the hesitancy of foreign teams to excavate, as the past instability of the region also hampered the possibilities of fieldwork by local teams. Under the rule of Saddam, foreign and local archaeologists were not permitted to collaborate on projects. The only position available to local archaeologists on foreign excavations was that of government or museum representative, a role that encouraged more policing than partnership. Rather than creating an environment for co-operation, this policy segregated archaeological efforts. This situation led to a stagnation not only in local research and dissemination of knowledge, but also in the training of young archaeologists in global theoretical and methodological trends. In addition to this, the sanctions placed upon Iraq for the actions of its government meant that little funding was available to expend on archaeological survey and excavation. Even now, the ongoing focus on military stability and national rebuilding efforts leaves little space for large-scale locally led projects. It is for this reason that collaborations are so essential to the future sustainability and growth of archaeological research in the region. Recognising this, co-directors Professor Elizabeth Stone and Dr Abdulameer Al-Hamdani used the excavations at Ur to create a vision for the future of Iraqi archaeology.

Collaboration is key: Rekindling archaeological partnerships

Before the Stony Brook excavations of 2015, there had not been a foreign team at Ur for over seventy years.Footnote 5 Interest in excavating the site was rekindled when Dr Abdulameer Al-Hamdani and Professor Elizabeth Stone accompanied an international team visiting the site on the 6th of June 2008 as part of an assessment of damage resulting from the ongoing Iraq War.Footnote 6 In the summer of 2011 they returned to the south of Iraq in order to assess the viability of an international excavation. Professor Stone returned towards the end of the year with a small team to dig at Tell Sakhariya (Zimansky and Stone Reference Zimansky, Stone, Stucky, Kaelin and Mathys2014). As stated in the site report, this project was “the first foreign expedition to Iraq (outside the Kurdistan/north-eastern region) since the war” (Al-Hamdani Reference Al-Hamdani2012: 17). The timing of the excavation matched the final US military retreat,Footnote 7 and it contributed to a renewed international push for fieldwork in southern Iraq. The project immediately set an important precedent in terms of relations between the foreign team and local archaeologists. Eight Iraqi archaeologists working on salvage projects in the marshes joined the excavations and participated in a series of lectures on modern recording and data-collection systems, as well as practical lessons in the techniques used by members of the international teamFootnote 8. In reciprocity, the international team was able to visit the marshes and was taught about the natural and cultural significance of the region. These bilateral efforts ensured the excavation's success at “reopen[ing] the scientific gate of co-operation that had been closed by the former Iraqi regime, and … rebuild[ing] cultural bridges between Iraqis and their international colleagues” (Al-Hamdani Reference Al-Hamdani2012: 17).

This spirit of collaboration set the tone for Stony Brook's continued work in the region and ensured that local authorities were welcoming when a request was made to excavate at the site of Ur in late 2012. This request came to fruition in 2015, when, after completing work at Tell Sakhariya, the team was able to begin fieldwork just a stone's-throw away from the ziggurat of Ur (Stone and Zimansky Reference Stone and Zimansky2016). A five-year permit for the project was granted to Professor Stone by Iraq's State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (Jihad Reference Jihad2015). By this point, several other teams were working in the region, and the Stony Brook group shared excavation facilities with a British team directed by Jane Moon, Stuart Campbell and Robert Killick excavating at Tell Khaiber and with an Italian team under the direction of Franco D'Agostino and Licia Romano working at the site of Abu Tbeirah.Footnote 9

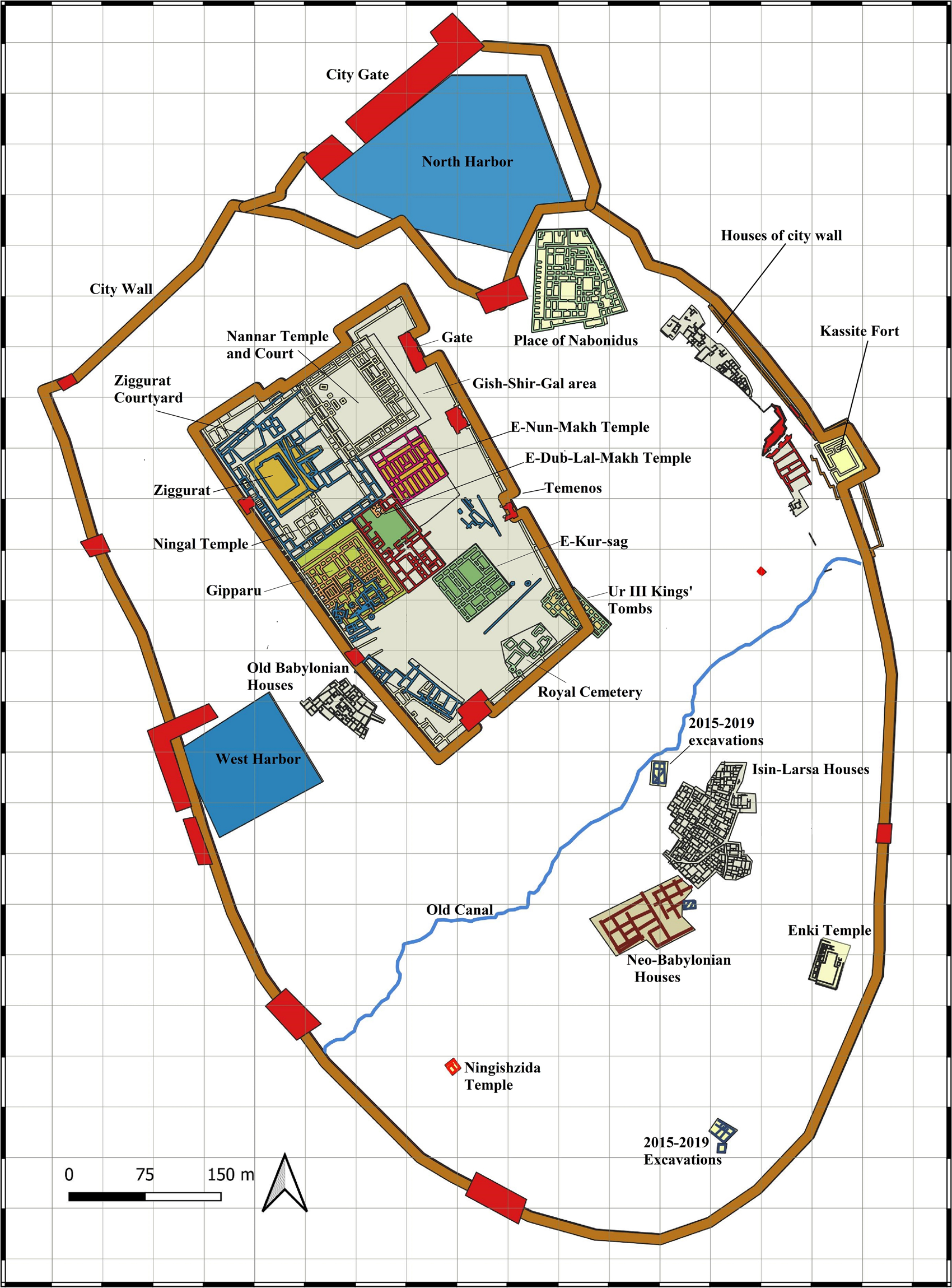

The aim of the Stony Brook excavations at Ur was to uncover Ur III domestic structures, in order to examine the socio-economic systems dominant in this period.Footnote 10 This aim is in contrast to past excavations in this region, where uncovering monumental public buildings and luxury items from rich burials had been the focus of research. According to Professor Stone, previous projects had been predisposed to elite histories, leading to assertions that Ur III society was extremely unequal.Footnote 11 However, recent research has indicated that these assertions are likely false, as the evidence uncovered so far “points to social mobility” where those in the city “could move up the economic ladder”.Footnote 12 In 2017 the work at Ur expanded as a team from Ludwig Maximilian Universität began a geophysical survey and targeted excavation under the direction of Professor Adelheid Otto, and an additional multi-method survey project was undertaken by Dr Emily Hammer from the University of Pennsylvania.Footnote 13 Fig. 2 shows the excavation areas.

Fig. 2 Map of Ur with main buildings and areas excavated between 2015 and 2019

As part of a wider effort to develop heritage management in the region, the directorial team developed a plan for the long-term preservation and accessibility of sites and collections, and for local training, outreach, and collaboration.Footnote 14 This included a small-scale training project, focusing on recent graduates in archaeology from the University of Kufa and the University of Qadissiya, all living in Dhi Qar province.Footnote 15

This initiative fits within a deepening awareness among foreign archaeologists that their focus on scientific results above social impact in the region has unwittingly contributed to local residents’ disconnection from local heritage and has sustained unequal management structures. Both issues have been further exacerbated by recent conflicts and have been met by a series of collaborative efforts, such as the British Museum's Iraqi Scheme and the EAMENA project.Footnote 16 The political and economic turmoil of the last decades has not only had the effect of devastating the physical traces of the past but has also affected the academic milieu in which they could be studied and their analyses disseminated. While local scholars were deprived of international resources, including financial support, the field of Middle Eastern archaeology as a whole lost its ability to call on cross-institutional expertise, as the knowledge and skill of local experts derived from a long and intimate engagement with archaeological materials was suddenly isolated as mobility was reduced. The rekindling of fieldwork at Ur thus provided an opportunity for both the international team and local trainees.

Training at Ur: Learning skills in the field

For about eight weeks, the Iraqi university students and the representatives and young researchers from the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH) worked at Ur with the international team, organising and carrying out archaeological fieldwork from research design to write-up.Footnote 17 Their time was divided between working in the field and lessons with local and foreign experts within the international team (Fig. 3). One of the most important lessons was research design in archaeology. The trainees were taught how to set out aims and parameters of an archaeological project in advance of commencing field research. As all fieldwork must be grounded in a deep knowledge of the region's history, as well as of archaeological theory, the trainees were given lessons in the history of southern Iraq and lectures on some of the most significant schools of archaeological thought in current research. This training was further enhanced through collaboration with the local workers who had a deep understanding of the site's history within the community, an aspect that is still too often undocumented in formal archaeological reports (Mickel Reference Mickel2021). A second element that is key to designing an efficient and archaeologically significant project is an understanding of on-the-ground realities. It was important that the students were aware of the resources available to them, as well as the problems that they might face in the field. In this case the presence of the SBAH representatives in the training sessions allowed the students to learn from their experience, preparing them for potentially taking on similar roles in the future. This collaboration also allowed for the area supervisors to learn from the experiences of the SBAH representatives who had carried out their roles on several sites and thus had a wealth of knowledge about the region.

Fig. 3 Trainees during a field lesson on surface artefact collection during survey (Photo: Imad Ali Abdul Hussein)

All these elements support the definition of feasible research questions that address a knowledge gap within the field. The research questions could then be coupled to tools and approaches appropriate to the site. These lessons would most often occur just after the daily fieldwork break, which meant that the trainees were able to visit areas other than those they had been allocated to, in order to observe a variety of excavation stages and architectural features and the different methods that are associated with these diverse factors. These factors dictate what data will be produced and thus what kind of conclusions one will be able to draw and what directions future research could take. As with any scientific endeavour, the project must be based on a hypothesis to be tested. However, one of the most difficult lessons for young archaeologists to learn is how to test a hypothesis and formulate a coherent argument without letting preconceived ideas skew analysis of the evidence. Trainees were asked to look critically at previous proposals and reports published in various archaeological journals, including Iraq, to help them identify the structures and requirements for writing their own proposals.Footnote 18

The next step after proposal writing and desk-based assessment for many projects is surveying. Before heading into the field, the trainees were shown the significance of using aerial and particularly satellite photography for the identification of sites. Professor Stone and Dr Al-Hamdani have extensive experience in surveying, GIS and the use of satellite photography to assess the damage to archaeological sites in conflict zones and shared their knowledge with the trainees. Another survey method uses remote sensing to identify buried structures or cavities, as well as changes in soil density or geomagnetic field. The primary methods used at Ur by the American and German teams in 2015 and 2017, respectively, were ground penetrating radar and magnetometry, and in 2017 in particular, the trainees benefitted from seeing the work of Dr Marion Scheiblecker, who undertook geophysical surveys across the south mound (Parsi et al. Reference Parsi, Fassbinder, Papadopoulos, Scheiblecker, Ostner and Bonsall2019). A less technologically dependent method included in the training was fieldwalking. The use of fieldwalking and controlled surface collection was almost non-existent in Iraqi archaeological projects, and although the trainees all had archaeology degrees, for many, the Ur project was their first encounter with these methods. Working with Dr Al-Hamdani and Dr Emily Hammer, the trainees, and in particular the students, became more familiar with the material culture of the site and were taught how surface observations could help to identify the date, layout and function of structures and assemblages below (Fig. 4).Footnote 19 This knowledge could then aid in selecting key areas that merit further investigation towards answering the project's research questions. The trainees also learned to record these features, quantify them and plot them in a grid using a total station. This information, along with the site's exact location and size, and the topography, vegetation and past uses of the surrounding landscape, could then be digitally documented to gain a full picture of the site's place within the region. To this end, all total station and GPS data from the surveys were input into a Geographic Information System, in this case ArcGIS. The trainees were able to experiment with this software to bring together and store various forms of spatial data in order to analyse and display it in useful ways. The resulting maps, tables and plans could then be used to assess wider issues within surveys, excavations and conservation efforts.

Fig. 4 Two students carrying out test-pitting as part of the survey of the south mound (Photo: Emily Hammer)

The skills gained through these surveying classes prepared the students for future work in the field. An understanding of a site's development within a wider landscape and an ability to identify cultural materials and their origins is essential to field recording. The students were divided among the various active research areas, with two working with the German team on the south mound and three divided among the Stony Brook trenches. When the German project ended after four weeks, all students were re-divided among the Stony Brook trenches, and in the final two weeks, a rotation was included so that students could participate in the survey and test-pitting organised by Dr Hammer. In participating in an eight-week-long project, the students became familiar with the deep history of the site and came to understand the tools and methods appropriate to different assemblages and materials. All the while, the students kept detailed field notes and made regular plans of the trenches. These plans were spatially anchored using the total station skills they had learned while surveying, as well as manual measuring techniques. The plans were supplemented with field photography and photogrammetry, an “image-based modelling technique” that can produce “geometrical and semantic information from images” (Gruen Reference Gruen, Reindel and Wagner2009: 288). In the field, the students learned about setting up cameras for publication photos and photogrammetry, adapting framing and lighting to the context or feature in focus. The students’ field notes were not meant to be just empirical descriptions of features, they were also expected to interpret these features and the assemblages found within them, giving evidence-based argumentation for their understanding of the socio-economic, political, and cultural systems that may have existed at the site through time.

Essential to these interpretations was an understanding of the processes of deposition, as well as the pottery typology used at Ur. The latter was taught in the field and during the post-excavation processing of finds, which mainly occurred in the early afternoon. By the end of the training, students were expected to understand how ceramics should be collected, recorded, and classified to determine site chronologies and context functions. To facilitate their ability to independently analyse materials in future and at other sites, the students were given pottery fragments and small finds to draw, photograph and interpret with the aid of the SBAH representatives and members of the international team. Their interpretations were further aided through the availability of online resources such as the Archives of Mesopotamian Archaeological Reports (AMAR) hosted by Stony Brook University and developed specifically with training and outreach in mind.Footnote 20 AMAR holds many digitised primary reports with detailed artefact descriptions and drawings, providing parallels for materials found at Ur. In addition to a focus on pottery and figurines as primary dating tools, the students also gained knowledge of Assyriology through studying the tablets uncovered throughout the excavation and analysed by Prof. Dominique Charpin, Dr. Anne Löhnert and Dr. Paola Paoletti, of zooarchaeology through studying the animal bones collected in the field with Melina Seabrook,Footnote 21 and of archaeobotany by carrying out flotation and heavy residue analysis.

Under a 1932 antiquities law, foreign archaeologists must turn all archaeological objects over to the Iraqi Museum. The SBAH representatives taking part in the training, Muntadher Alouda, Fadhel Hassan and Hayder Mohammad, were thus involved in teaching the official documentation needed for the museum, as well as in the excavations and recording process. Each evening they would work in the lab to register every object that was to be acquired by the museum, and they were present when the finds were brought to the museum. Through these activities, the students and international team members were able to learn the local processes of museum registration. As many Iraqi archaeology graduates go into museum work, this is an invaluable skill for many within the group. Aside from a finds register, the museum and Directorate of Antiquities require an excavation report summarising work carried out during the season, the major finds, and archaeologists’ interpretations of the site. In the final weeks of the project, the students wrote their own reports, based on their notes and in-depth consultation with their trench supervisors. These summaries received feedback from Dr Al-Hamdani and were presented to the trainee group. As the culmination of the project, the summaries highlighted what the students had learned throughout their eight weeks at Ur.

Reaping the rewards: Building the foundations for the archaeology of tomorrow

The Ur training project was an enormous success, with both the international team and the trainees expressing great enthusiasm and improving their collaborative archaeological work and analysis. The students showed considerable progress. By the end of the excavations, they had come to understand the archaeological process at the site and were able to independently work in their own areas, exhibiting initiative, curiosity, and conscientiousness. They collaborated with the international archaeologists and the local workmen to facilitate the efficient and careful excavation and recording of the site. At the same time, the international team learned about local heritage structures and management practices, improving communication and streamlining documentation strategies between recording in the field and post-excavation.

The hope for the future of this project is that the trainees will continue to work in the field and teach the next series of students, based on their experiences. Over the following years, the trainees gained further experience in archaeology through local projects and museum work. Several of the students went on to work on other projects organised by international teams, indicating their continued dedication to the archaeology of the region and their willingness to work in partnership with a variety of teams, ever expanding their skills and networks for future independent research.Footnote 22 Their commitment to bettering local practices in archaeology will be instrumental in the project's ultimate aim of “develop[ing] the abilities of the next generation for future field work” (Al-Hamdani Reference Al-Hamdani2017). The programme's objective is that the practical experiences obtained will aid trainees in overcoming difficulties in the post-war job market and will augment the precarious safety of heritage in conflict areas. Using the skills gained through the training programme, several of the students have the experience to supervise areas and even lead their own excavations, bringing in the research methods and management strategies that they carried throughout the project. For international team members, the traineeship was equally a networking experience, as they were able to develop strong bonds with local archaeologists, creating an environment in which future partnerships can flourish.

The networking opportunities are an important element to the training project. Besides the close collaborations forged with SBAH representatives and workers, throughout the project students had the opportunity to engage in additional cultural activities that explored the history of the region and highlighted its need for protection. They attended a number of events within the local community, both scholarly seminars and formal ceremonies officiated by local government, and they aided in the interpretation of the site for visiting media personnel and educational groups. These experiences helped them develop the communication, presentation and diplomatic skills needed to flourish in an environment of cross-institutional scholarly collaboration, as well as instilling an understanding of the need for the widespread and varied dissemination of excavation results, incorporating academic communities and a wide range of external stakeholders. Through such events and dissemination strategies, the students develop the contacts needed to independently set up projects and assert their rights as equal partners in archaeological collaborations.

Ideally all archaeological work in Iraq would be based on partnership and mutual teaching. This would highlight that foreign-led projects in the region not only hold academic relevance to a distant university and funding body, but also have local relevance to those living and working around the sites being excavated. Such projects foster local stewardship, ensuring that, if a site does become caught in future conflict, local archaeologists can use their connections, skills and expertise to manage the heritage record in a way that preserves as much of the site information as possible, and that they can assess damage to the site once the area has been re-secured. For international team members, the collaborations established also mean that in such cases information and resources can be shared across national boundaries. These considerations have become increasingly significant for the south of Iraq as the threat of terrorist occupation has mostly subsided and efforts to rebuild are well under way.

Possible Futures: Expanding the success of the training project

Additional opportunities for collaboration between different excavation teams and their associated institutions exist and could be leveraged within this environment. As many of the teams already publish, present and organise field resources together, the training programme could formalise and expand existing links.Footnote 23 This would allow for larger-scale bids for funding and a more consistent and continuous training programme.

As highlighted above, a number of the trainees who took part in the Ur training programme went on to work on other excavations and heritage management projects, and prior to the field season, the students had already done some surveying in Eridu as a means of preparing them for a full-scale excavation. An extended ‘curriculum’ would allow trainees to further build on previous knowledge and experience to learn more advanced skills, improving their ability to independently undertake and manage research. With funding bodies like the Nahrein Network supporting the work of young Iraqi scholars, it is becoming more feasible for them to obtain international funding for their own projects. Additionally, former participants could serve as links between various existing projects, also connecting them with the local community of archaeologists and administrators, mirroring the role that Dr Al-Hamdani holds for teams in the region.

If we compare the Ur project to other outreach initiatives taking place across Iraq and the Middle East, we find there are additional elements that could prove to be beneficial additions to the existing project. One useful training project in Iraq to date is the British Museum's Iraq Emergency Heritage Management Training Scheme, which combines excavations at two sites, Darband-i Rania in the north and Girsu/Tello in the south.Footnote 24 Similar to the Ur training programme, this project focused on preparing professionals to stabilise the archaeology of the country post-conflict. The programme was divided into two sections spanning six months, with six to eight participants each time. The first section was a three-month visit to the British Museum, where the Iraqi professionals attended seminars delivered by leaders in archaeology and heritage studies from various cultural institutions. This initial training included excavation and post-excavation techniques, public relations skills, dissemination practices, and lectures on the challenges of modern archaeological research, including heritage law and strategies for combating site looting and black market antiquities trade.

One of the issues encountered during the Ur training programme was that the trainees regularly had to leave the trench mid-workday to find time for the seminars. They also had little time in the afternoons to engage in post-excavation work, due to the long commute to and from the site each day. By including a longer learning period before the fieldwork component, there would be more time to develop theoretical concepts, giving participants more freedom to explore their particular interests in the field. While a pre- or post-season training period abroad would be a desirable addition to the existing training programme, further funding would be required for this type of expansion. Perhaps more feasible would be a series of lectures offered at local cultural institutions, with Iraqi professionals presenting in person and online seminars from international scholars. Visits could be made to nearby sites and post-excavation work could be undertaken with representatives from the Nasiriyah and Baghdad Museums. This would encourage the development of a strong local archaeological support network, with students, directors, curators, and conservators sharing resources and skills without the need for external stimuli.

Other institutions are focusing training on recording methods that do not require being on site. Simultaneously with the Ur excavations, the organisation for Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA), a collaboration between the Universities of Oxford, Leicester and Durham, was given 1,813,223 pounds by the British Council to develop a training programme that focuses on ‘Endangered Archaeology Methodology’ in areas where physical access to sites is limited (British Council 2017; EAMENA 2017). The programme spans more countries than just Iraq, also including Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Occupied Palestinian Territories, and Tunisia, and it includes short courses and one advanced course for 140 archaeologists covering “the acquisition and analysis of existing satellite data and air photo records and the use of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and digital records management” (British Council 2017). Held at five cities across the region – Baghdad, Amman, Tunis, Cairo, and Beirut – these courses work according to teaching materials and guidelines that are adapted to the workings of the EAMENA database. Such focused projects provide opportunities for archaeologists with extensive field experience to develop their technical skills together with colleagues from across the Middle East. Such a programme would not act as a replacement for the Ur training programme, but rather as a deepening of the programme for those who have already worked their way through the initial phases.

A further example of a successful training initiative is the Smithsonian's project based in the north of Iraq. The Smithsonian established a 22-week programme in Erbil on ‘Fundamentals in Heritage Conservation’ to bring local heritage professionals up to speed on recent American and European developments in heritage management practices.Footnote 25 Following this, Smithsonian researchers worked alongside professionals from the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, to “document and stabilise the recently liberated ancient site of Nimrud” (Smithsonian 2017b). This included the extensive re-mapping of the site and assessment of the damage to the site in comparison to archaeological records from the previous century. By combining their fields of expertise across local archaeology and international heritage conservation practices, the two teams were able to draw up a heritage management plan for the site, which looked towards rebuilding its research and touristic infrastructures, while preserving it for the future. While the Smithsonian focuses on one site, Nimrud, a similar initiative could be developed for sites in the centre and south of Iraq, from Babylon to Ur. In the case of Ur, the ziggurat in particular has been damaged by active assaults and by a lack of restoration work since Saddam. The monument receives a large number of tourist visits throughout the year that, without proper upkeep, have led to a great deal of damage to the structure. There is little tourist infrastructure, and although mitigation plans were suggested in the past, financial and security issues have long denied any possibilities for their implementation. The current interest in the site following its inscription on the UNESCO world heritage list serves as an ideal opportunity for the trainees to aid in forming a heritage management project, one that could develop the facilities of the area, ensuring continuing local investment in the archaeological site.Footnote 26

Since 2017, a joint UK-Iraqi initiative, the Nahrein Network, has provided resources for preserving natural and cultural heritage in Iraq (UCL 2017). With similar aims to the Ur project, although on a much larger and more integrated scale, the Nahrein Network works to strengthen local Iraqi archaeological expertise and create collaborative endeavours to promote the longevity of cultural heritage in Iraq. Inside Iraq, the network provides grants for locally-led research and engagement projects. The network mentors, trains and supports young Iraqi scholars locally throughout their projects. Like the British Museum initiative, the Nahrein Network also facilitates the mobility of Iraqi scholars to the UK, and it funds placements for Iraqi heritage professionals and scholarships for Iraqi students at UK institutions. These initiatives ensure the creation of networks between the two countries that are further encouraged through regular online and in person events. Their final initiative, the Iraq Publishing Workshops, is particularly innovative. It provides training and support for early career academics in Iraq to publish their research in international journals. This does not just increase their citations, but more importantly ensures that their work is recognised and that their ideas are disseminated to scholars around the world. Publication is not an area that was considered in the creation of the Ur training programme, but as the Nahrein Network indicates, it is essential to address “the problem of low publication figures among Iraqi academics, lack of sufficient exposure to interdisciplinary methodologies and the widening gap and the emerging friction between the small number of Iraqi academics who have been educated outside Iraq and those who have not” (Nahrein Network 2021).

Another recent addition to the list of collaborative training projects in Iraq is the Education and Cultural Heritage Enhancement for Social Cohesion in Iraq scheme (EDUU) funded by the EU. Similar to the Nahrein Network, this large-scale project comprises a multi-pronged model in which local capacity building at different levels could ensure long-term impact. As part of this scheme, the Universities of Bologna and Turin, in collaboration with the University of Baghdad, the University of Kufa and SBAH, have undertaken outreach initiatives with community members and training courses with young archaeologists. This included small-scale field training initiatives during their surveys in the Tūlūl al-Baqarat area (Wasit) and the Najaf and Qadisiyah regions, as well as organising courses in English, survey technologies and heritage management (EDUU 2021; Lippolis et al. Reference Lippolis, Bruno, Quirico, Taha, Mohammed and Taha2018). The latter courses were mostly held in Iraq, in Qadisiyah, Baghdad and Kufa, although the more technically oriented courses focusing on GIS and photogrammetry were undertaken in Italy. Unfortunately, the excavation, training and outreach initiatives were hampered by the emergence of COVID 19, but it is still clear from the work achieved prior to the spring of 2020 that this project integrated a number of important initiatives. It combined fieldwork, post-excavation processing and heritage management to ensure a holistic engagement with the archaeological process. It also ensured funding for resource development on the ground, rather than solely focusing on training in high tech methods abroad with no long-term implication for teams working independently in Iraq. Finally, this training scheme is combined with wider collaborative activities that incorporate the whole community, including consultations and activities with site workers, local inhabitants, school children and museum professionals, among others. Hopefully, the successes of these kinds of multi-pronged project will encourage more large-scale funding initiatives around archaeology and heritage management that allow for the creation of a sustainable model for knowledge exchange and capacity building.

Conclusion

The training programme at Ur has proven to be a successful small-scale prototype for collaborative training and fieldwork within the archaeological sites in the Dhi Qar region. The students involved contributed to the creation of a more extensive record of the archaeological site, bringing their own skills and knowledge to the excavation. Their experience in the field ensured their support for additional archaeological projects in the region, giving them further opportunities to develop their abilities and contacts, achieving the aim set by the Ur training project in its initial funding application.

Building on this initial success and drawing on other research projects around the region, there continues to be room for future growth. Further funding and cross-institutional cooperation could allow for a deepening of the project, giving former students the ability to come back as educators, working with new trainees before fieldwork aspects of the project, to cultivate their knowledge of archaeological theory, the history of the region, its material manifestations and methodologies applied in the field. Additional expansions could include skill-specific courses for selected programme alumni, either locally or abroad, encouraging interests in heritage management and remote site recording.

By creating an atmosphere of collaboration rather than one of separation, the training project at Ur contributes to the creation of a positive environment for future projects in the region, in which the imbalance in Iraqi archaeology, created by a history of colonialism, war and Saddam's policy of disunion, can be redressed. Beyond Iraq, it provides a model for other nations in the Middle East working through a period of post-conflict reconstruction or academic isolation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to give a special thanks to Prof Elizabeth Stone, the director of the Ur excavations, for her support and guidance in writing this article, as well as to Karrar Jamal for his help in supplying figures, and to Khawla Ajana for the Arabic translation of the abstract.