1. Introduction

Limited liability is viewed by many eminent contemporary corporate law scholars as a defining attribute of the business corporation (e.g. Armour et al., Reference Armour, Hansmann, Kraakman, Pargendler, Armour, Davies, Enriques, Hansmann, Hertig, Hopt, Kanda, Pargendler, Ringe and Rock2017; Clark, Reference Clark1986). The importance of the invention of limited liability has been compared to that of the steam engine, and likened to the discovery of electricity. It has been presented as an essential precondition for the development of widely held corporations, stock markets and industrial economies (Halpern et al., Reference Halpern, Trebilcock and Turnbull1980; Manne, Reference Manne1967).

When and how did limited liability become such a defining attribute? Conventional wisdom suggests a single well-defined watershed invention (or discovery), which implies a date, or at least a well-defined era. The literature (e.g. Armour et al., Reference Armour, Hansmann, Kraakman, Pargendler, Armour, Davies, Enriques, Hansmann, Hertig, Hopt, Kanda, Pargendler, Ringe and Rock2017; Micklethwait and Wooldridge, Reference Micklethwait and Wooldridge2003) typically identifies the limited liability statutes of the mid-19th century. Scholars focusing on Britain typically point to the Limited Liability Act 1855 and the Joint Stock Companies Act 1856.Footnote 1 Critics view these dates as a turning point for the worse, ushering in, an era of irresponsibility, in which rentier investors were able to escape responsibility (Ireland, Reference Ireland2010).

Some have attempted to reconcile theory with history by pushing the date back in time, even if implicitly (Bainbridge and Henderson, Reference Bainbridge and Henderson2016). Several recent historical studies have focused on the emergence of the very first business corporations, the English and Dutch East India Companies, around 1600 (Dari-Mattiacci et al., Reference Dari-Mattiacci, Gelderblom, Jonker and Perotti2017; Gelderblom et al., Reference Gelderblom, De Jong and Jonker2013). Other studies have asserted that limited liability was indeed available from the very first business corporations but became generally available in 1855 and uniformly used shortly thereafter (Johnson, Reference Johnson2010). The invention of limited liability has thus been credited with both the rise of the stock market and the commercial, financial and transport revolutions of the 17th and 18th centuries, and the industrial revolution of the 19th century.

At the same time, the importance of the limited liability attribute of the corporation has been downplayed, on the grounds that shareholders' liability (with the exception of tort liability) could be limited by contract. The presence or absence of the limited liability attribute was not decisive, from this point of view, it only increased transaction costs, without making them prohibitive, and these costs could be reduced by other means. The new important attribute was entity shielding, the protection of corporate assets from shareholders' creditors, because this corporate attribute, unlike limited liability, could only be achieved by statute (Hansmann et al., Reference Hansmann, Kraakman and Squire2006).

I am convinced by the argument that entity shielding cannot be achieved contractually, that its importance has been neglected, and therefore that its study is a major contribution. Yet I think that before downplaying the role of limited liability, we should study its history and impact more carefully. Indeed, the history of corporate limited liability has not yet been studied systematically for the full 400-year span of the history of the business corporation. Despite the disagreements among scholars about the timing of its origins, there has been no comprehensive attempt to examine the timing of its creation and settle the debate. In this paper, I will investigate the historical development of corporate limited liability, combining my own earlier research of various episodes in this history with studies by others of additional historical episodes.

My argument, in a nutshell, is that it is a mistake to view limited liability as a well-defined watershed invention, with an earlier period in which it did not exist and a later period in which it existed. I conceptualize its emergence process as being divided into three definable periods, linked by two critical transition phases. In Period I – from the establishment of first joint-stock business corporations around 1600 until around 1800 – there was no notion of the attribute of limited liability and no actual manifestation of it as such. I will show that the corporation was used for asset partitioning but not for owner shielding. Next, in the first transition phase, there were small but significant steps towards forming the attribute of liability and distinguishing it from the legal personhood attribute. Paradoxically, however, the separation of the liability attribute from the personality attribute gave rise to the unlimited liability corporation, not the limited liability corporation.

By Period II – from around 1800 until around 1930 – the concept of limited liability had been moulded, a continuum of unlimited and partly limited regimes had been created, and diverse types and levels of limitation of liability had been experimented with. Various types of partial owner shielding or partial limited liability were offered and tried.Footnote 2 The second transition phase, leading into to Period III – from around 1900 until the mid-20th century – was characterized by a gradual convergence into a single, universal model, that I term here ‘limited liability in the modern sense’, and Hansmann et al. term strong owner shielding. It can be present only in an environment in which: (a) business corporations have both equity investors and long-term financial creditors; (b) some corporations become balance-sheet insolvent; (c) a procedure for liquidating insolvent corporations is available; and (d) creditors have legal priority over equity investors in claims to corporate assets. In such circumstances, it exists only if creditors do not have access to, or can be legally barred from accessing, any of the private assets of any of the shareholders; creditors can collect only from the pool of corporate assets, not from the pools of personal assets of the shareholders. Limited liability in this sense became general only in the 20th century, not by statutory intervention, but rather by contractual opting into this regime by most business corporations.

It was amid the convergence process characteristic of the second transition phase that public intellectuals celebrated the ‘invention of limited liability’ during what I here call Period II, and it was in the post-convergence Period III that legal-economic theoreticians laid out the theoretical arguments supporting the proclamation that without limited liability, the entire corporate economy could not have developed. By contrast, this paper establishes the origins of limited liability in the modern sense in the second transition phase, with the implication that this attribute was not essential for the spread of widely-held and publicly-traded corporations, or for the unfolding of the industrial revolution and the sustained economic growth that followed.

For the sake of brevity, I focus primarily on Period I, the explanation for the transition to Period II, and on Period II. The transition to Period III and Period III require a separate and expanded study, and are only outlined here. I examine four levels: the actual legal liability regimes; the ideas, namely the conceptualization of limited liability and the theoretical analysis of its advantages; the take-up rate of various liability regimes by corporations across various sectors; and lastly the impact of the legal regime on economic outputs and growth. The first level, that of the development of liability regimes, is at the core of the periodization proposed in this article.Footnote 3

2. Period I: before the conceptualization of limited liability, 1600–1800

By the late Middle Ages, jurists viewed the corporation as having several distinct traits. Most importantly, it had a legal personality separate from that of its members (Harris, Reference Harris2000). The formation of a corporation created asset partitioning. The corporation as a legal personality could own distinct pool of assets. Individuals who acted as agents on its behalf (in their capacity as mayors, abbots, deans or masters) could convey its assets and contract on its behalf subject to authorization. By doing so, they did not assume individual legal liability. Nor did they create individual personal liability among the members of the corporation, be they guild members, university doctors or monks. Rather, whether corporate officers acted by seal, deed or otherwise, they placed assets and liabilities with the corporations they governed (Williston, Reference Williston1888). This was the effect of the corporation's legal personality. It formed asset partitioning that had nothing to do with owner shielding from creditors. It had nothing to do with the future attribute of limited liability in its modern sense.

Indeed, these jurists could not conceptualize limited liability in its modern sense as one of the attributes of corporations, as these were not-for-profit entities and had no equity investors. Nor was limited liability a relevant privilege for early corporations: they held most of their assets in immovable land; their tort liabilities were not expected to be considerable; they did not transact commercially or have joint-stock capital; they were unlikely to be deeply in debt or insolvent; and they could not be dissolved by their creditors.

2.1 The early business corporations: the East India Companies

The first large-scale long-lasting joint-stock business corporations were the English East India Company (EIC), established in 1600, and the Dutch East India Company (VOC), established in 1602. Both engaged in long-distance oceanic trade with Asia around the Cape of Good Hope, and both combined the legal concept of a separate entity with the financial scheme of joint-stock investment. This consolidation of the joint-stock with the corporate entity enabled a lock-in of the investments. The corporation which already acquired early in its history the features of a separate pool of assets and collective governance added now also the lock-in feature. The partitioning of assets into the EIC and VOC was not designed in order to provide owner shielding from creditors.

The EIC's most distinctive attribute, as evident in its first charter in 1600, was its incorporation as ‘one body corporate and politic’. As a separate legal entity, it had a full set of legal capacities and privileges to own land, litigate in court and hold franchises such as monopoly. The charter made no mention of joint-stock finance or of limiting the liability of its members (Harris, Reference Harris2020). For the limited liability attribute to have become an issue in the early history of the EIC, it would have had to be financed by both equity and debt. However, debt was initially only a marginal source of corporate finance, due to the high level of uncertainty in the early stages of trade, the high level of on-going risk, the absence of tangible collaterals, and the non-existence of commercial banks or bond markets of the magnitude that could provide long-distance finance. The company was financed almost exclusively by equity, while commercial credit was used only on a small scale, as an integral part of commodity transactions. Thus, there was no significant conflict between shareholders and creditors, and no need to define the liability of shareholders for corporate debt. Some degree of asset-partitioning was evident from the fact that the company was a separate legal entity, but this should not be confused with limited liability in the modern sense.

The EIC started using long-term debt finance only during its challenging years before the Glorious Revolution. The 1685 balance sheet recorded a debt of £783,890 (some of it short-term) and an equity of £1,703,422 (Chaudhuri, Reference Chaudhuri1978: 424). After the Revolution, the company became a financial intermediary, issuing bonds to the investing public, and a lender to the government. At this stage, in theory, it could have become insolvent, and the question of the relative priority of bondholders over shareholders – and related questions of how to limit the personal liability of its shareholders to company debts – could have become an issue. But they did not. The EIC's relationship with the government may have made the company ‘too big to fail’.

The VOC was chartered 2 years after the EIC, in 1602, by the States-General, the Federal Assembly of the Dutch Republic. The charter positioned the company as an entity separated from the state and other parties with the capacity to own property, transact and hold privileges (such as a monopoly or franchise) issued by the state. Unlike the EIC, the VOC's charter also addressed the financial scheme.Footnote 4 It contained permission to issue a public offering of shares, granted all residents of the Netherlands the right to subscribe to them, and locked-in the capital thus raised (6,424,588 guilders) for 10 years.

Was the liability of VOC shareholders limited in the modern sense? Prominent economic historians of the company (Gelderblom et al., Reference Gelderblom, De Jong and Jonker2013) have argued that, by 1623, the VOC was a limited liability corporation.Footnote 5 When the Middelburg Chamber postponed paying import duties in 1611, the Zeeland tax collectors did not seize the VOC property but threatened the directors with imprisonment for debt instead. From this, these authors concluded that the directors bore personal liability for company debt, and may have inferred that passive shareholders (participanten) enjoyed limited liability. In 1623, it was resolved that the text of bonds would be rewritten to explicitly exclude creditors' recourse to the signatories' person or property.

I think that this interpretation of historical facts is misjudged. The VOC liability regime is confusing because, unlike the EIC, it had two classes of shareholders: the aforementioned passive participanten and the active bewindhebbers. The passive shareholders were entitled only to a share in the profits. The VOC also had two levels of governance, six city Chambers and a united company.Footnote 6 The active shareholders served by their status as the governors of their respective city Chambers and could be appointed as the united company's directors (members of the Herren XVII). The liability of the passive shareholders of the VOC was not defined in the charter or anywhere else (de Jongh, Reference de Jongh and Koppell2011). Clause 42 of the VOC Charter specifically exempted directors, who were also the active shareholders, from salary debts. The charter does not refer to the event of insolvency and dissolution.

The VOC was initially financed exclusively by equity investment. When resorting to debt finance, each VOC City Chamber borrowed according to its needs and at the discretion of its directors (active bewindhebbers). The survey of VOC bonds by Gelderblom et al. (Reference Gelderblom, De Jong and Jonker2013) shows that City Chamber directors contracted loans on their personal account, pledging their person and goods. This personal borrowing may have resulted from the fact that the chambers, unlike the VOC itself, were not viewed as separate legal entities. The question of whether passive shareholders had limited liability was muted by the fact that active shareholders assumed personal liability. In 1617, the directors centralized borrowing and resolved that henceforth they – and not the City Chambers – would make borrowing decisions. In 1622, bonds were no longer issued and signed by the directors, but by the bookkeepers, and they no longer carried the signatories' customary guarantee of person and goods. But this happened because the VOC was a legal personality and the directors ceased borrowing personally, acting instead as VOC agents borrowing on its behalf. There is no evidence that the liability regime applying to passive shareholders in the event of insolvency and dissolution was defined in 1602, in 1623 or at any later stage, or that the liability attribute of the VOC was separated from the legal personality attribute and conceptualized as a limited liability attribute in the modern sense.

Over the following years, the VOC's resort to longer-term debt finance increased because, unlike the EIC, it did not raise additional equity investment beyond the initial public offering of 1602. However, the mid-life VOC was backed by the state and was never under real risk of insolvency. When the VOC became insolvent in 1799, the Dutch government revoked its charter and nationalized the company's territorial possessions in Asia, its assets and debts (Sinninghe and van de Vrugt, Reference Sinninghe, van de Vrugt, Solinge, Gepken-Jager and Timmerman2005). Limitation of liability, as we understand it today, was irrelevant throughout its entire history.

In short, the two largest corporations of the 17th and 18th centuries, the EIC and the VOC, had thousands of shareholders each. Their paid-up capital was in the millions and their shares were traded successfully in high volumes on the Amsterdam and London Stock Exchanges – and all of this was achieved without limited liability being one of their key features.

2.2 The corporate economy begins to expand

The Bank of England was formed in 1694 by an Act of Parliament and a charter. Neither defined the Bank as having limited shareholder liability, yet this did not prevent the company from opening public subscriptions for a capital of £1,200,000. The offering was fully subscribed, with 1,520 shareholders contributing from £25 to £10,000 each (Bank of England, 2018). In 1720, two new marine insurance corporations were formed, the London Assurance Company and the Royal Exchange Assurance Corporation. The two were fully incorporated, but their shareholders did not have limited liability. From the 1760s, further insurance companies were established in the fire and life insurance subsectors. These were unincorporated and their shareholders were not shielded by a corporate entity.

The fastest-growing corporate sector of 18th-century Britain was canals. In 1766, bills were introduced in Parliament for two schemes, the Trent and Mersey Canal and the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal. Both were conceived as joint-stock corporations (Harris, Reference Harris2000). In the following decades, no fewer than 122 acts were passed for the incorporation of joint-stock companies for the construction of canals, and more than £17 million was raised by canal companies in the period before 1814. The Grand Junction Canal, the largest of all, required 18 times more capital than the Staffordshire and Worcestershire (£1,800,000 compared to £100,000) (Ward, Reference Ward1974: 29–30, 43–46).Footnote 7 Canal Acts typically incorporated the canals as legal entities but made no reference whatsoever to the liability of shareholders.Footnote 8 The financial model relied on equity investment, initially from local investors, provincial financial markets and exchanges, and, over time, from the national market and the London Stock Exchange.

The main instrument for raising additional capital downstream, which was often needed as the canal projects came in over budget, was by additional calls on the original shares. For this purpose, the nominal value of canal shares was high, while the initially called-up capital could be as little as 10% of the nominal capital. Bank loans were rare. Some of the companies borrowed from public investors by issuing bonds, sometimes convertible into stock and usually secured by the future toll income. Hence, in most scenarios, the shareholders bore the risks of loss of investment. Thus, once again, limited liability in the modern sense did not feature here. Even if debt finance had been used extensively, in the event of insolvency, creditors could have collected the uncalled capital from shareholders, which was often much greater than the called-up capital.

2.3 Jurists, courts and legal discourse around corporations

On the level of legal discourse and legal doctrine, historians have offered three indications that a doctrine of limited liability already existed in the late-18th century (DuBois, Reference DuBois1938). First, shareholders could not, in practice, be arrested for the debts of the company in which they held shares; thus, they could not be forced to pay its debts. Second, an Act of 1662 confirmed the exemption of shareholders of certain trade corporations from bankruptcy procedures by holding that they were not traders.Footnote 9 Third, it can be inferred from a judgment of 1671 that, when a corporation was not authorized to make further calls upon its members, the debts of the corporation could not be collected from them.Footnote 10 My interpretation of these three doctrinal pieces is that it was the legal personality attribute of the corporation that provided the rationale for them.

The first general statute of Parliament that dealt with joint-stock companies was the famous Bubble Act of 1720. This statute was enacted amid the wild days of the South Sea Bubble, in which numerous joint-stock companies were floated and speculative trade in company shares reached an all-time peak. This Act prohibited the formation of undertakings that pretended to act as joint-stock business corporations without obtaining a Charter or Act of Incorporation:

All undertakings … presuming to act as a corporate body … raising … transferable stock … transferring … shares in such stock … without legal authority, either by Act of Parliament, or by any Charter from the Crown, … and acting … under any charter … for raising a capital stock … not intended … by such Charter … and all acting … under any obsolete Charter … for ever be deemed to be illegal and void.Footnote 11

Note that it prohibited companies from pretending to have legal personality, joint-stock or transferable shares. But there is no mention of pretending to have limited liability for shareholders. Companies that bypassed state incorporation and turned directly to investors in the market did not view limited liability as a lucrative attribute that could attract investors to their companies.Footnote 12 I take this striking absence as further support for my claim that, in 1720, limited liability as a separate attribute had not yet come into being.

In his comprehensive digest of mid-18th-century English law, Blackstone (Reference Blackstone1765: 462) wrote:

After a corporation is so formed and named, it acquires many powers … Some of these are necessarily and inseparably incident to every corporation … The five core attributes: to have perpetual succession, to sue and be sued by its corporate name, to purchase lands, and hold them, to have a common seal and to make by-laws.

Limited liability is not mentioned by Blackstone – either by this name or even as an idea. It is also entirely absent from the most significant English book on corporations of the 18th century, Kyd's (Reference Kyd1793) Treatise on the Law of Corporations. Indeed, no scenarios of insolvency of corporation or claims of creditors are even discussed, so the absence is not just of the term or the concept, but of the entire circumstances in which equity holders and creditors are in conflict and the liability of shareholders can be defined.

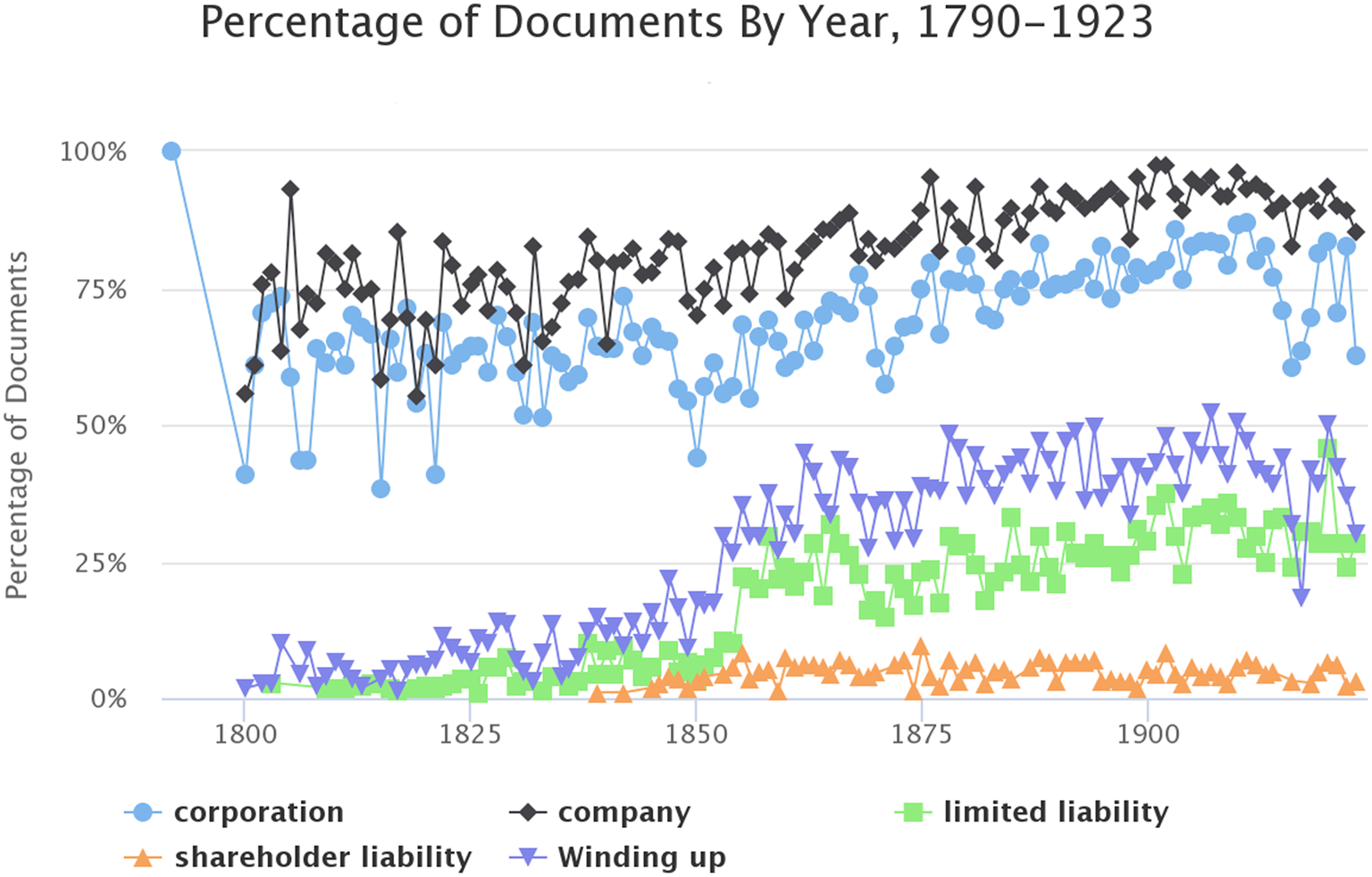

The inexistence of the concept of limited liability in legal works published in Period I and its rise in the transition to Period II is illustrated in the following digital text analysis of the most exhaustive collection of legal treatises of American and British law, Gale's Making of Modern Law: Legal Treatises 1800–1926 database (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Occurrence of relevant terms in The Making of Modern Law database.

The terms ‘limited liability’ picked-up gradually in the first decades of the 19th century. The term ‘winding up’ that indicates the ability to dissolve insolvent companies also picked up simultaneously. The terms ‘company’ and ‘corporation’ that were used as control group show up frequently from the beginning of the century. A terminological control ‘shareholder liability’ was not used by contemporaries throughout the century.Footnote 13 As the coverage of the database begins only in 1800, a Google Ngram Viewer analysis (on all Google Books) was run for the period 1600–1900. No mention was found before 1773 and only a handful of mentions were found in books published in the period to 1820.

Limited liability in the modern sense kicks-in only when the corporation is not only insolvent but is also being dissolved because of this. In 16th-century British law, the Crown could create a corporation at will (through a charter) and could also revoke a charter at will, thereby terminating the corporation. But by the 17th century, the Crown could no longer arbitrarily dissolve corporations; and misuse of charters had to be reviewed by the court through the writs of quo warranto or scire facias before a charter could be rescinded. By the 18th century, the main means of liquidating a corporation was through special act of Parliament (Blackstone, Reference Blackstone1765), the effect of which was noted by Kyd (Reference Kyd1793: 516):

The effect of the dissolution of a corporation is, that all its lands revert to the donor; its privileges and franchises are extinguished; and the members can neither recover debts which were due to the corporation, nor be charged with debts contracted by it, in their natural capacities.

This statement comes nowhere close to reflecting limited liability. Insolvency is not mentioned as grounds for dissolution; the dissolution is not viewed as a collection measure on behalf of creditors; and the rationale for extinguishing the debts is based on the death of the corporate legal entity. Indeed, until the 19th century, bankruptcy procedures, both in Britain and the US, did not apply to corporations, only to individuals. Insolvent corporations could only be dealt with by Parliament. The affairs of the York Buildings Corporation exemplify the impossibility of swiftly dissolving an insolvent corporation. This entity was first incorporated by a letter patent issued by King Charles II in 1665 and was reincorporated after the Glorious Revolution in 1690. During the South Sea Bubble of 1720, it became involved in high-risk speculations, including lottery schemes. From then on, its financial state was shaky, at best; and its creditors, sensing it was insolvent, attempted to collect on their debts. But despite numerous litigations, it took an Act of Parliament to dissolve the company in 1829, over a century after the first signs of financial insolvency (Cummings, Reference Cummings1980; Murray, Reference Murray1883). At no stage during these century-long proceedings could the issue of personal liability of shareholders be discussed, because the corporation was not dissolved and its inability to pay its debts in full was not ascertained.

2.4 Legal personality is not limited liability

In sum, the corporation went through a fundamental organizational transformation around 1600. It became a for-profit entity with joint-stock capital, lock-in of capital and transferable shares. Within a few decades, business corporations with thousands of shareholders and an active market for corporate shares were thriving, and dominating long-distance Eurasian trade (Harris, Reference Harris2020). They did not need, and hence did not develop, owner shielding in the form of limitation on shareholders' liability. Nor did the Bank of England and the insurance corporations established during the post-1688 financial revolution. This was also the case with the canal corporations of the 18th century transport revolution.

As I have demonstrated, the period between 1600 and 1800 simply predates the emergence of the attribute of limited liability in the modern sense of owner shielding. Corporations then were not unlimited, but they were not limited either – hence, the continuum of limited to unlimited liability had not yet been formulated. One should not read my argument as claiming the attribute of limited liability existed but was not yet conceptualized in this period. What was absent was not conceptualization of limited liability, but the relevance of owner shielding from creditors. What may have misled some scholars are the manifestations of the separate legal personality of the corporation. The implication of the legal personality attribute of the corporation was that the corporation formed asset partitioning, in the sense of owning assets and governing them. But without debt finance, without a procedure for dissolving insolvent corporations, without the legal ability to determine whether shareholders would bear liability in insolvency, owner shielding was a non-issue and limited liability in the modern sense could not yet exist. In this era in which the legal personality attribute created asset partitioning, the level of liability of shareholders could not be tuned. The conflict of interest and related agency problem between creditors and equity investors was not yet created. The distinction between adjusting and non-adjusting creditors was not yet formed. One could not yet envision a liability bearing shareholder or a veil piercing that would subject shareholders to liability towards creditors.

3. The transition to Period II: the emergence of unlimited liability, 1780–1830

It was somewhere between 1780 and 1830, namely during the transition from Period I to Period II, that owner shielding became relevant and shareholder liability evolved as a distinct attribute, detached from the legal personality attribute of the corporation. But it did not become a binary attribute: the choice was not between liability or no liability; rather a full continuum of possible values was formed. I will substantiate this argument by calling attention to important developments that the literature has hitherto overlooked. I will show that, counterintuitively, the separation of the liability attribute from the personality attribute gave rise to unlimited liability, not to limited liability. In this period, shareholders of a corporation could be made liable, in full or in part, for corporate debts, something that was impossible in Period I. This point was missed by the literature and is established here for the first time.

3.1 Unincorporated and unlimited

The unincorporated company was a new organizational form created in Britain in the second half of the 18th century. This form was a bypass, created out of necessity, given the reluctance of the Crown and Parliament (and the opposition of vested interests) to incorporate new business corporations following the South Sea Bubble (Harris, Reference Harris2000). Unincorporated companies were formed by shrewd lawyers at the service of businesspersons in the realm of private law. These lawyers used legal devices, such as private contracts, the common law partnership and particularly the trust, to hold assets in a single pool, turning the company's directors into trustees that governed these assets (DuBois, Reference DuBois1938). Such companies acquired the financial attributes of joint-stock capital and transferable shares, but they could not enjoy the status of a separate legal personality (which could only be provided by the state in the realm of public law). These were the first large firms that did not use the corporate entity as a platform and consequently the first whose shareholders had direct personal liability with respect to third parties.

Because their shareholders were not shielded as a side effect of the separate legal personality of the entity, unincorporated insurance companies often limited the liability of shareholders towards insured persons contractually through clauses in the insurance policies. But shareholders were fully exposed to tort liabilities and to contractual liabilities that were not explicitly limited in written contracts. The trust device was also used to shield shareholders as trust beneficiaries from debts created by the trustees, but courts applied partnership law to unincorporated companies in order to overcome the shielding effect of the trust. Thus, shareholders in unincorporated companies were liable for the company's debts insofar as these were not limited in contracts with third parties. It became evident that, in the absence of supporting legislation, a joint-stock company could be formed with or without limited liability. Entrepreneurs could consider whether to invest the effort and money required to apply for full incorporation or settle for the unincorporated and unlimited form. Hence, limited liability had taken its first step towards being a separate and desirable attribute.

3.2 Drafting incorporation acts

Somewhat similarly, the shift from incorporation by charters to incorporation by private and special Acts of Parliament created a way of defining the limitation of shareholders' liability separately from legal personality. In the chartering era, the Crown used a template that included a standard legal personality clause (like the ‘body corporate and politic’ clause in the EIC charterFootnote 14) but made no reference to shareholder liability. When incorporation moved to Parliament, drafting was openly negotiated between entrepreneurs, parliamentary agents and MPs, meaning that limitation of liability could be included in incorporation acts. Explicit clauses dealing with shareholder liability gradually became more common.

Toward the end of the 18th century, limited shareholder liability became a declared motive of entrepreneurs who petitioned for incorporation, claiming it was essential for the success of their undertakings.Footnote 15 In his Trader's and Manufacturer's Compendium, Montefiore (Reference Montefiore1804) wrote that incorporation was indeed sought ‘principally for the purpose of exempting the shareholders from any responsibility as partners’ (p. 235). Thus, unlike the 18th century canal companies, by the early-19th century, some level of limitation of liability was an important motive for seeking incorporation.

The issue then filtered back to charters. In 1825, the Bubble Act of 1720 was repealed. This statutory repeal legalized, subject to the common law, the formation of unincorporated companies (Harris, Reference Harris1997). The second section of the 1825 Act gave the Crown discretion to grant charters without full limited liability.Footnote 16 This, according to Attorney-General Copley, the drafter of the repeal Act, would make law officers more willing to grant charters, and would encourage promoters to apply for charters rather than for Parliamentary Acts of incorporation.Footnote 17 We also learn in retrospect, from the fact that in 1825, a specific legislative arrangement had to be made to legalize the granting of charters without full limited liability, that limitation of liability had not been considered an attribute dealt-with by charters until then.

3.3 The general incorporation acts

General incorporation legislation created the opportunity (and need) to define the attributes of corporations, including their liability regime. Here we shift our attention to the US, because the earliest of these acts were drafted and passed there. New York was the first jurisdiction in the world to enact general incorporation law in 1811, initially only for manufacturing companies (Hilt, Reference Hilt2008). The Act Relative to Incorporation for Manufacturing Purposes of 1811 served as a model for similar acts enacted in New Jersey in 1816 and Connecticut in 1837 (Cadman, Reference Cadman1949; Kessler, Reference Kessler1948). Its terms included a low maximum capitalization of $100,000, a short life of only 20 years and a shareholders' liability provision (Section 7):

… all debts which shall be due and owing by the company at the time of its dissolution, the persons then composing such company shall be individually responsible to the extent of their respective shares of stock in the said company, and no further.

This Act has been positioned by some historians of US corporations as the first declaration of general limited liability, albeit for manufacturing companies (Wright, Reference Wright, Irwin and Sylla2010). But Howard (Reference Howard1938) convincingly shows that the case law that interpreted and applied it did not view it as creating full limited liability in the modern sense. In the cases of Slee v. Bloom (litigated between 1816 and 1823) and Briggs v. Penniman (litigated between 1819 and 1826), the judges were uncertain how to apply Section 7. Eventually, Judge Woodworth of New York's Court of Error held that: ‘Every stockholder, in a company of this description, incurs the risk of not only losing the amount of stock subscribed, but is also liable for an equal sum, provided the debts due and owing at the time of dissolution, are of such magnitude as to require it.’ This is what Howard (Reference Howard1938) justly terms ‘double liability’. Thus, while liability was perceived in the 1811 Act as an attribute separate from legal personality, a mandatory double liability regime was set.

In the first half of the 19th century, Massachusetts granted the highest number of corporate charters of any American state. The charter of the first Massachusetts manufacturing corporation, granted in 1789, contained no reference to individual liability. This was often the case in late 18th-century charters, but some provided that if a judgment against the corporation remained unresolved for 6 months after its dissolution, it should be satisfied out of the private property of the members. Several early 19th-century charters stipulated that if a judgment could not be collected from a corporation, individual shareholders were personally liable. Hence while Massachusetts refused to grant limited liability to any manufacturing corporation in the early-19th century, it did separate the attribute of shareholders' liability from that of the corporation's separate legal personality. This did not, however, create universal limited liability in the modern sense.

3.4 Corporate liquidation procedures

As we have seen, in the era of incorporation by charters and special Acts of Incorporation, dissolution could only be realized by a revocation of the charter or repeal of the act. Creditors could not take an insolvent corporation to court and liquidate it. In the UK, a procedure for the winding-up of companies was first made possible with the Joint Stock Companies Winding-Up Act 1844,Footnote 18 enacted immediately after the Joint Stock Companies Act 1844,Footnote 19 which had made available general incorporation by registration, thus also rendering a winding-up procedure necessary. The procedure applied to registered companies was similar to the bankruptcy procedure applied to individuals. Now, for the first time, with permission from the Chancery Court, creditors could dissolve insolvent companies to collect from their shareholders. The dissolution of registered companies was thus connected to the earlier doctrines applying to the dissolution of partnerships (Getzler and Macnair, Reference Getzler, Macnair, Brand, Costello and Osborough2005).

In the US, the Constitution made bankruptcy a federal issue and incorporation a state law issue. This fact made the US path to corporate liquidation different from the British one. The short-lived Bankruptcy Acts enacted by Congress in 1800 and 1841 did not apply to corporate entities, and there was significant opposition to such application on constitutional grounds. It was argued that, as corporations were created by states, they should also be liquidated (exclusively) by states. But the growing interstate nature of railroad corporations weakened this constitutional view. Corporations were permitted for the first time to take advantage of the 1867 Bankruptcy Act, which covered all legal persons, including corporate persons. Corporate insolvency became a major issue in the 1870s, during a wave of railroad companies' failures. The Bankruptcy Act provided corporate liquidation procedures via federal courts and state judiciary used equity receivership tools to avoid the liquidation of large concerns mid-way through construction of essential railroad lines (Skeel, Reference Skeel2001). This opening of the road for the dissolution of insolvent corporations brought the question of the shareholders' limited liability regime to the centre stage.

3.5 Debt finance

Debt was not a significant component of corporate finance in Period I and in the transition to Period II and thus cannot explain the transition. Furthermore, the late creation of corporate insolvency and bankruptcy procedures in Britain and the US can be explained by the low demand for such mechanisms in the corporate economy of Period I. Debt only gradually became a (secondary) source for financing the large infrastructure projects of the transport revolution. The loans for river and turnpike projects were more municipal than private and were secured by tolls. Canals and railroads were financed initially by locally floated equity investment. Often, shares in canals and even railways were traded locally on provincial stock exchanges (Baskin et al., Reference Baskin, Baskin and Miranti1999; Evans, Reference Evans1936; Ward, Reference Ward1974). Debt finance was only sought when investment was required from non-locals at an informational disadvantage, such as London investors for canals in Yorkshire, or for US railroads (Chandler, Reference Chandler1954). To reduce risks, the debt was raised after equity had been raised locally in the region served by the route in question, and once the real estate of the project could be offered as a security.

The financial sector was the exception in the sense that both banks and insurance firms had creditors as part of their normal course of business, policy holders and depositors. Initially, insurance was organized in the Lloyds marketplace in which underwriters assumed personal liability and in unincorporated companies with unlimited liability. Banking was mostly organized as family banks and partnerships with personal liability. The exposure to personal liability placed the financial sector in the forefront in Period II, earlier in the US in which the financial sector switched to the corporate form around the turn of the19th century and later in Britain beginning in the second quarter of the century (Kingston, Reference Kingston2007).

The corporate bond market emerged only in Period II. The total number of corporate debentures listed in 1860 on the UK Stock Exchanges was just nine, all in railway ventures, and their nominal par value was just £5.8 million (Coyle and Turner, Reference Coyle and Turner2013). The corporate bond market grew slowly, and by the 1880s was still composed mostly of railway bonds. The real par value of bonds and the par value of bonds per GDP reached a peak in 1909. The small (compared to equity) and slow-growing (in real terms and compared to GDP) corporate bond market in such a late period simply cannot explain the transition from Period I to Period II and the separation of the limited liability attribute. The separation of the liability attribute is not a story of shareholders calling for a limitation of their liability in the face of growing need for debt finance. The intensification of a conflict between creditors and equity investors did not present itself in Britain or the US before the late 19th century. It might explain the second transition but not the first.

4. Period II: a continuum of liability regimes, c. 1800–1900

In the transition to Period II, the liability attribute was separated from the personality attribute and conceptualized. In Period II, the attribute became a dimension, a continuum, along which various liability regimes were created. Actual companies adopted various liability regimes. Full liability in the modern sense, as well as complete unlimited liability, was not adopted by many jurisdictions, sectors and companies. As we shall see, this is an important period in terms of experimentation with various liability regimes offering partial owner shielding and evaluating their impact on economic performance. Bear in mind that this experimentation went hand-in-hand with the formulation of corporate liquidation procedures and the expansion of debt finance. The question of the direction of causation between the growing debt finance and changing liability regimes has to be studied, yet it is beyond the scope of this article.

The introduction of unlimited liability companies and of companies with a variety of liability regimes, which were not full limited liability in the modern sense, did not constrain the expansion of joint-stock companies in the economy, to the contrary. Jurisdictions without full limited liability grew fast and the number of companies in these jurisdictions exploded. The number of joint-stock companies in the UK grew from 24 in 1740 to 61 in 1811 and 216 in 1834. The total nominal capital of these companies grew from £20 million in 1760 to £90 million in 1810, rising to £240 million in 1844. They expanded into growth sectors such as gas lighting, mining and railroads, and by 1840 more than 35% of the British economy, in the sectors relevant for incorporation, was incorporated in joint-stock companies (Harris, Reference Harris2000). The circle of investors widened correspondingly, as is evident in the ownership of railway companies, while shares in unlimited companies were traded regularly on a liquid market, as is evident in bank shares (Acheson et al., Reference Acheson, Campbell and Turner2017; Rutterford et al., Reference Rutterford, Green, Maltby and Owens2011).

4.1 Unlimited liability jurisdictions

As we have seen, the development of the conceptualization of limited shareholder liability as a distinct attribute emerged out of the conceptualization of unlimited liability. State jurisdictions realized they could select where to position themselves on the liability continuum, and some opted for unlimited liability.

In America, Massachusetts, unlike New York, opted to position itself at the unlimited liability end. Did this negatively affect economic development, as many have suggested? The short answer is ‘no’. Its unlimited liability regime did not prevent Massachusetts from being the most advanced corporate economy in the US in terms of the number of charters issued to manufacturing. Following a wave of business failures in 1829, the Massachusetts Act Defining the General Powers and Duties of Manufacturing Corporations was passed in 1830. The law imposed a charter clause that limited the liability of shareholders to the unpaid balance on the shares (Hilt, Reference Hilt, Collins and Margo2016). A century later, no less a corporate law authority than Dodd (Reference Dodd1948) observed that the textile industry in New York, a jurisdiction with general limited liability (double liability) for manufacturing companies since 1811, grew no faster or larger than in Massachusetts, where it was introduced a full two decades later. In other words, the leading industry of the time (textiles) in a leading industrial state (Massachusetts) seems not to have been adversely affected by holding on to a regime of unlimited liability during this crucial pre-1830 industrialization phase. This suggests that limitation of shareholders' liability was not a major factor, given the financial structure of the companies and the available winding-up procedures. Massachusetts and other New England states gradually adopted and extended limited liability laws. But there is no evidence, from the current state of research, that they did so because unlimited liability had retarded their economic growth.

4.2 General limited liability

In Britain, the Limited Liability Act 1855 did not impose limited liability in the modern sense. It did not even put forward a default limited liability rule. It allowed incorporators to decide how much shareholders would personally owe creditors by determining how much of the nominal capital was not to be paid up initially. No single liability model derived from this Act. The Companies Act 1862 similarly stated:

The Liability of the Members of a Company formed under this Act may, according to the Memorandum of Association, be limited either to the amount, if any, unpaid on the Shares respectively held by them, or to such amount as the Members may respectively undertake by the Memorandum of Association to contribute to the Assets of the Company in the event of its being wound up.Footnote 20

The 1862 Act did not set a default rule that incorporators could opt out of either. Liability had to be drafted by the incorporators into the Memorandum. This enabled the incorporators – and later, the directors – to design the desired level of liability by determining the level of nominal capital and varying the percentage of that capital that was actually paid up. This drafting also opened the way for the use of reserve liability, to which we will turn later.

4.3 Liability for unpaid balance

The common practice of issuing only partly paid company shares, which began with canals and railway companies, continued also after the enactment of the aforementioned 1855 and 1862 Acts. It was initially a response to gradual cash-flow needs of construction projects, but was eventually also used as security for corporate creditors. While in some canal and railway companies only 10–20% of the capital was initially called up, the gap narrowed as the 19th century progressed and paid-up capital reached 50–70% by the third quarter of the century (Acheson et al., Reference Acheson, Turner and Ye2012; Jefferys, Reference Jefferys1946; Shannon, Reference Shannon1933). In Harris (Reference Harris2013), I concluded that by 1897, the average paid-up capital of our sample was 70% (Harris, Reference Harris2013: 34–35).Footnote 21 It follows that, as late as the turn of the 20th century, the practice of issuing shares that were not paid in full was still common in Britain. As long as this practice continued, limited liability in the modern sense was therefore not yet the dominant practice.

4.4 Divergent liability regimes in banking

In Britain, the divergent continuum of liability regimes was manifested in banking more than in any other sector. Acheson et al. (Reference Acheson, Hickson and Turner2010) provide the most comprehensive survey of liability regimes in the banking sector in England, Scotland and Ireland. A handful of banks were state-chartered: Bank of England (est. 1694), Bank of Ireland (1783), and the three Scottish banks – Bank of Scotland (1695), Royal Bank of Scotland (1727) and British Linen Bank (1746). But these banks were not explicitly chartered with the limited liability attribute, because their establishment predated its separation from the personality attribute. Up until the mid-1820s, these banks enjoyed the privilege of being the only note-issuing banks in England and Ireland to be organized as corporations. Other banks were excluded from this organizational form and were not permitted to have more than six partners. In this way, they were also excluded from the unincorporated joint-stock form.

Parliament permitted the incorporation of unlimited liability joint-stock co-partnership banks in Ireland by means of the Banking Copartnership Regulation Act (1825), and in England by the Banking Copartnerships Act (1826). An 1826 statute legalized the unlimited joint-stock banks in Scotland.Footnote 22 The liability of shareholders in such unlimited banks was joint and several. I interpret these Acts as a manifestation of the separation between the personality and liability attributes of the corporation. They also reveal that the older chartered banks were at some point re-conceptualized as having a shareholder-limited liability attribute separately from their legal personality attribute. For example, by 1825, the Bank of England (which, as we have seen, was not established with limited liability in mind) was understood to have this attribute. By 1826, unlimited liability joint-stock banking had become available throughout the UK. Banks were excluded from the initial Joint Stock Companies Act 1844 and the Limited Liability Act of 1855, but by 1858, they were allowed to incorporate by registration with limited liability. This enabling legislation abolished the distinction between chartered banks and registered limited-liability banks.

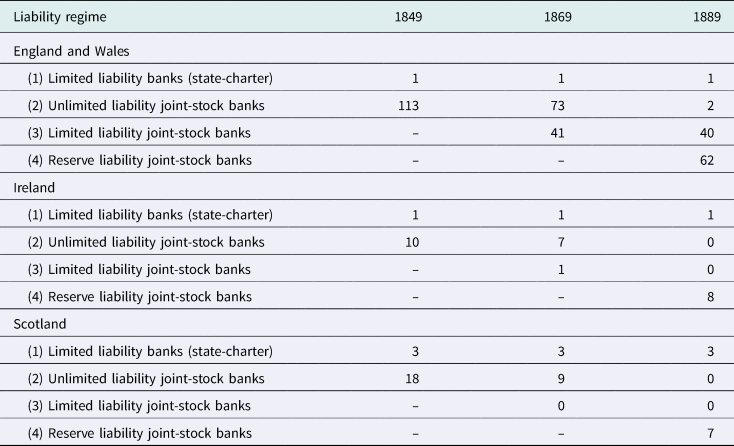

The study conducted by Acheson et al. (Reference Acheson, Hickson and Turner2010) illustrates my contention regarding the divergent liability continuum by showing that the banking sector in Britain did not converge into one single liability regime in the 19th century, but rather came to enjoy a choice of four regimes (see Table 1):

Table 1. Liability regimes in UK banking, 1849–1889

Source: Adapted from Acheson et al. (Reference Acheson, Hickson and Turner2010: 250).

Hence, more than one liability option existed, and more than one option was selected during each of the three time-points surveyed by Acheson et al. (Reference Acheson, Hickson and Turner2010). We can observe that absolute unlimited liability had disappeared by 1889, but there is no sign of convergence to limited liability in the modern sense during the period covered in their study. Questions for historical empirical researchers remain. For now, we can conclude that the banking sector in England, Scotland and Ireland seems to have functioned for a significant time without limited liability in the modern sense.

4.5 Reserve liability

The fourth and last type of bank liability to appear in UK banking in the 1880s was reserve liability. Enacted in the aftermath of the City of Glasgow Bank's collapse, the Companies Act 1879 intended to facilitate the conversion of existing unlimited joint-stock banks to limited liability companies. The main innovation was the creation of ‘reserve liability’ – a sum of capital that could be called only upon insolvency and liquidation of the company. Unlike uncalled capital, which could be used by the directors of solvent companies to complete projects, reserved capital was only used to protect creditors. Again, reserve liability offered a continuum rather than a single liability regime. Many banks selected double or triple liability, and others had different multiples of nominal par-value of the shares.

Reserve liability was also common in the US. Some states imposed double liability on all corporate shareholders, while many imposed it particularly on banks. This requirement was initially imposed by clauses in specific charters and then in state general statutes, and even state constitutions. In 1863, the Federal Government entered the field of banking regulation with the National Banking Act, which stipulated that ‘each shareholder shall be liable to the amount of the par value of the shares held by him, in addition to the amount invested in such shares’. Most states implemented the federal legislation in their own laws, making shareholders in banks bear proportionate double liability (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg1985).

Proponents of the evolutionary-convergence-to-efficiency hypothesis may view Period II as a brief and unremarkable stage during which inefficient liability configurations were rejected in favour of the most efficient organizational regime – limited liability in the modern sense. Yet this is an instructive period, in which for more than a century different configurations of shareholder liability along a continuum were selected by different jurisdictions, sectors and companies, some of which performed very well under regimes that were different from limited liability in the modern sense. A period of growing economies, expanding sectors and successful enterprises at the height of Western industrialization cannot be dismissed as a mere hiatus. We can gain important historical and policy insights from the liability experimentations made in this period.

5. The transition to Period III: convergence to uniform limitation, 1880s–1930s

Limited liability in the modern sense first appeared in Period II. Yet in that period, this liability regime was adopted only by a small number of business corporations, and the vast majority of corporations in the UK and the US were located towards the middle of a continuum between unlimited liability and full limited liability. In both jurisdictions, the decades between the late-19th century and the mid-20th century marked a critical turning point in corporate liability history, worth of scholarly attention in its own right. These were decades of transition from Period II to Period III, during which most corporations moved towards the full limited liability end of the continuum. Contrary to the first transition period which had led to a divergence of liability regimes, during the second transition period, the menu of available regimes converged to a single model – that of limited liability as we recognize it today.

Jurisdictions that had made unlimited liability the mandatory regime in the early 19th century now, one by one, shifted to a default of limited liability. As we have seen, Massachusetts did this in 1830. Rhode Island was the last New England state to enact limited liability for manufacturing companies.Footnote 23 Gradually, perhaps with the exception of the banking sector, general incorporation acts that included the limited liability attribute and some level of default limitation expanded beyond manufacturing.

Interestingly, California was slower to turn to the fuller limitation of liability of shareholders, opting instead for pro-rata unlimited liability, which was not fully abolished until 1931 (Weinstein, Reference Weinstein2005). Yet the late introduction of the limited liability regime did not prevent California from achieving a greater growth rate than most other US states. I am not arguing that a significant share of California's growth rate should be attributed to the pro-rata liability regime, but merely pointing to the absence of a compelling argument that the lack of full limited liability slowed down its phenomenal growth or prevented its big businesses from expanding. Indeed, we know that the shift to a limited liability regime had no significant effect on share prices, which suggests that the previous regime did not repress the value of corporations (Weinstein, Reference Weinstein2003).

In the British case, as we have seen, the Companies Act 1862 enabled incorporators to design the liability regime of a corporation in its Memorandum of Association. The Memorandum could establish a ‘company limited by shares’, in which shareholders were liable only for the unpaid balance on the shares, or a ‘company limited by guarantee’, in which shareholders undertook to contribute a set amount in the event of the winding-up of the company. The 1862 Act, which became a model for company acts throughout the British Empire, was thus an enabler. It allowed the formation of companies with limited liability in the modern sense as well as companies with liability for unpaid-up capital with varying percentages of paid-up capital and reserve liability, with different multipliers. The selection of the liability model was made at the level of the individual corporation. The convergence to a single liability model did not happen at the statute level either. We know that the process of convergence took decades to complete, but its exact rate and timing are under-studied and deserving of additional investigation. As we have seen, in the 19th century companies in a variety of sectors had partially paid-up shares. The use of unpaid capital as means of creditors' protection was given up in the 20th century as its effectiveness fell into disrepute (Armour, Reference Armour2000; Miller, Reference Miller1995). In the early 20th century, it was one of the components that contributed to the convergence to limited liability in the modern sense.

Reserve liability, be it double liability, triple liability or other multipliers, could be achieved at either the corporate level or the regulatory level. Insofar as I can tell, initially, different corporations selected varying levels of liability, but during the transition to Period III, the voluntary adoption of double or triple liability eventually faded out. One notable exception was the banking sector. As we have seen, in England in 1889, 40 banks with full limited liability operated alongside 62 reserve liability banks, while reserve liability remained a feature of British banking until the mid-1950s (Turner, Reference Turner, Dimsdale and Hotson2014).

In the US, reserve liability (in the form of double liability) was imposed by state and federal regulation. The double liability requirement for new banks was revoked in federal banking regulation in 1933–35. The Great Depression and the introduction of deposit insurance as part of the New Deal are often considered as the main motives for this revocation. The federal act that applied to existing banks was repealed in 1959. State-level laws and bank charters gradually gave up on reserve liability as well (Macey and Miller, Reference Macey and Miller1992).

The transition to full limited liability in the modern sense took place on two levels: the statutory level and the practical-contractual level. On the statutory level, the mandatory requirement for some level of shareholders' liability, be it unlimited liability, pro-rata liability, double or triple liability, was revoked. On the practical level, the practice of issuing partly-paid shares diminished and the default of full limited liability was adopted by practically all public corporations and most private corporations.Footnote 24

6. Period III: the era of limited liability from the 1930s

As soon as the transition to Period III neared completion, statements about the utmost importance of limited liability and its essentiality to the modern economy were made with growing frequency and prominence. In an oft-cited 1911 speech before the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, long-serving President of Columbia and future Nobel Peace Prize recipient Nicholas Murray Butler famously declared: ‘I weigh my words, when I say that in my judgment the limited liability corporation is the greatest single discovery of modern times … Even steam and electricity are far less important than the limited liability corporation, and they would be reduced to comparative impotence without it’ (Butler, Reference Butler1911: 47).Footnote 25 In 1926, The Economist made a similar sweeping assertion: ‘The economic historian of the future may assign to the nameless inventor of the principle of limited liability, as applied to trading corporations, a place of honour with Watt and Stephenson, and other pioneers of the Industrial Revolution’.Footnote 26 Such statements could not have been made in the decades that followed the Limited Liability Act 1855 and the Joint Stock Companies Act 1856 because most companies had not yet converged to limited liability in the modern sense.

Statements about the historic importance of limited liability as a game-changing invention were theoretically substantiated a few decades later with the emergence of economic analysts of corporate law in the 1960s and beyond. Manne (Reference Manne1967) argued that the modern corporation, with shares held by numerous passive shareholders, could not exist without the attribute of limited liability. If shareholders holding small stakes were subjected to unlimited liability to corporate debts, then investors with personal wealth would be reluctant to invest in public corporations because every single share would place all their personal assets at risk.Footnote 27 To guard against this, without the protection of limited liability, risk-averse investors would be forced to concentrate their investment in a single firm, in which they had access to information via employment or a management position, or in which they could justify the high costs of monitoring. Only the invention of the limited liability corporation, argued Manne, would allow the investor to spread risks by holding a diversified investment portfolio.

Halpern et al. (Reference Halpern, Trebilcock and Turnbull1980) added a further dimension to the theoretical importance of limited liability, noting that it is essential for stock markets to operate efficiently: without it, shares would not be priced uniformly and efficiently. Shares held by deeper pockets would allow the company to borrow more cheaply and be more profitable. The personal wealth of shareholders and their holdings in other corporations would affect the value of the corporation in which they buy or sell shares. Thus, the price of shares in the same corporation would be affected by the personal wealth of the buyer and seller of those shares.

Taken together, these arguments provide the theoretical support for the claim that limited liability was pivotal for the emergence – or at least for the efficient functioning of – the corporate economy, in which the larger firms were organized as corporations with numerous shareholders and tradable shares.Footnote 28 Manne and Halpern et al. were exposed only to Period III in the history of limited liability, and built their arguments without recourse to historical analysis. Their arguments fail to explain how public corporations, having a large number of shareholders and tradable shares, developed before the convergence to limited liability in the modern sense.

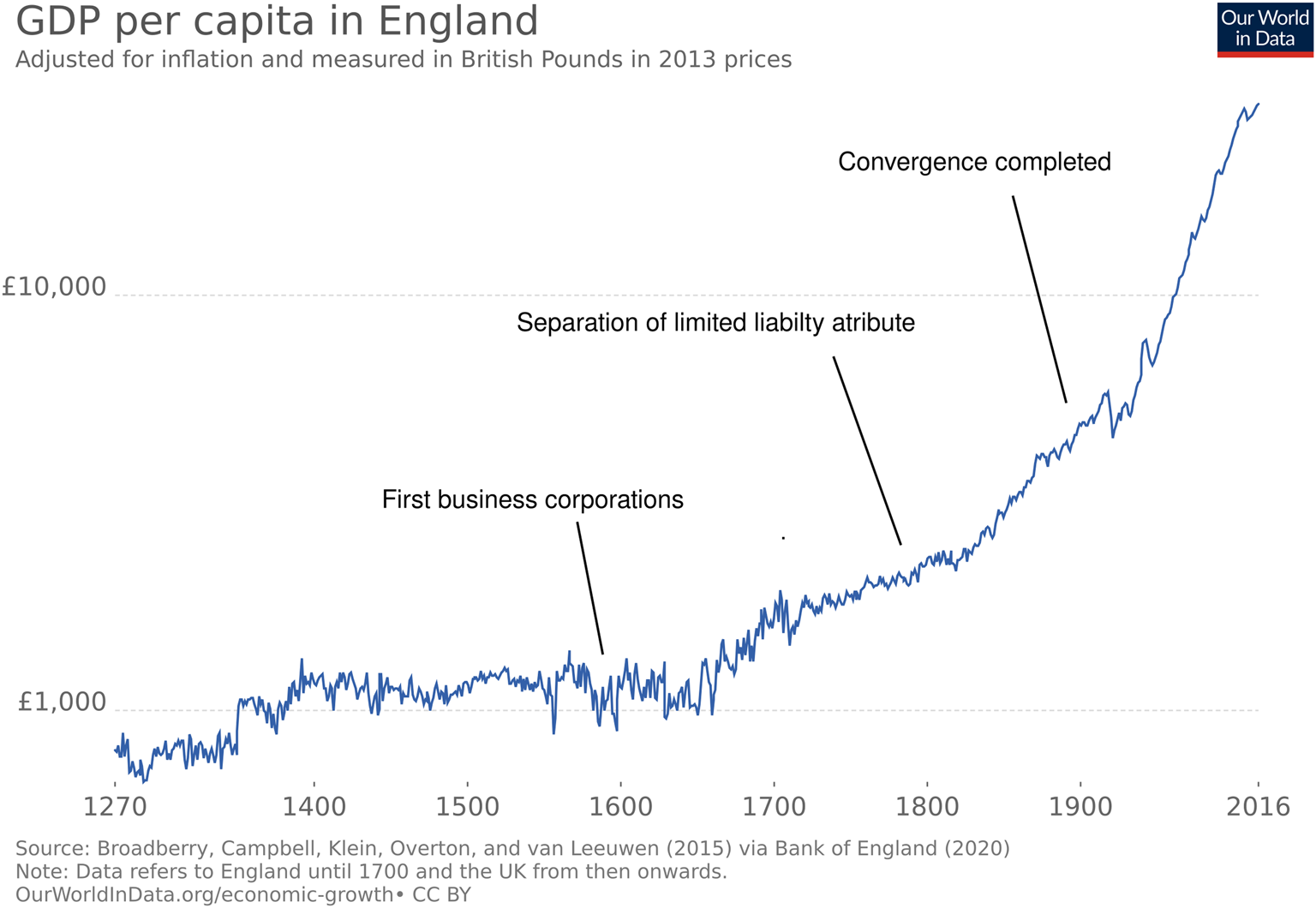

The corporate economy and the stock market began to function in our Period I, long before limited liability in its modern sense first manifested. An economy comprising thousands of public corporations, featuring hundreds of thousands of shareholders and liquid stock exchanges in which wide segments of society invested, expanded over the course of our Period II, in the era of divergent liability regimes. These corporations – with their unlimited liability, liability to unpaid capital, and double and triple liability – contributed significantly to the GDP growth of industrialized economies up until the end of the 19th century (Figure 2). Economic growth did not start or take off in the mid-19th century with limited liability legislation.

Figure 2. Growth of GDP per capita in Britain and periodization of limited liability.

Obviously, careful econometric studies are needed before one can establish the impact of the rise to dominance of limited liability in the modern sense on economic growth. But until such studies are conducted, there is no reason to hold that limited liability had a dramatic impact, or that the periods that predated it did not have a flourishing corporate economy with a vibrant stock market.

7. Conclusions and implications

This article argues that both common narratives of the history of the origins of the limited liability attribute of the business corporation, namely that it was created with the very first business corporations and that it was created with the general limited liability acts of the mid-19th century, are mistaken. Limited liability in the modern sense was not an attribute of the first business corporations around 1600, and the Limited Liability Act 1855 in Britain was not a watershed in the history of this attribute. This article argues that the preconditions for the relevance of owner shielding from creditors and the manifestation of the attribute of limited liability in the modern sense were created both in Britain and the US in around 1800. The understanding that shareholders could be liable, or not, for corporate debts, and that corporations could have unlimited liability, was new. The first turning point in the history of limited liability was the separation of this attribute from the legal personality attribute and the creation of a new dimension offering different liability regimes. The second turning point, more than a century later, was the completion of a process of convergence into a single, uniform and universal liability regime at the far end of the continuum that made full limitation of shareholder liability the standard. Limited liability in the modern sense, full owner shielding, I contend, is therefore less than a hundred years old.

So, what does the revisionist history of limited liability offered here convey with respect to the legal and economic theory of limited liability and the impact of limited liability in the modern sense on economic performance? The entire corpus of corporate finance that has developed since the 1950s assumes that publicly traded corporations have limited liability in the modern sense. The theories of limited liability that were developed since the 1960s contrast full limited liability with unlimited liability. The new historical understanding offered here narrows the conditions in which these theories actually apply. Scholars should not conveniently assume that the convergence was an evolutionary drive to efficiency and that the outcome of the convergence – full limited liability in all sectors including the financial sector – is necessarily ‘first best’.

Consider the example of investment banking, the last major sector to converge to the modern liability model. Until 1970, the New York Stock Exchange required that investment banks be organized as partnerships in which partners could be personally liable for debts. In three waves (in the early 1970s, around 1985 and lastly with Goldman Sachs in 1999), investment banks all eventually became corporations with limited liability and went public. Not long thereafter, in 2007, three of these banks, Bear Stearns, Morgan Stanley and Lehman Brothers, had an unprecedented debt-to-equity leverage ratio of over 30, and others were not far behind. The rest of the story is familiar: the 2007 subprime crisis, the 2008 collapse of the investment banks, $1,250 billion in accumulated losses suffered by banks worldwide, and the US and European government financial bailout to the tune of $4,100 billion. I do not argue here that the crisis and losses were caused exclusively by the convergence of the financial sector into a full limited liability regime. But higher leverage, assumption of higher risks and intense conflicts of interest between creditors and equity investors are a possible ramification of the limitation of liability of hitherto personally liable partners.

I do not wish to claim that the prevailing theory of limited liability is worthless. It captures well the shortfalls of unlimited liability. Full unlimited liability is a non-starter in the 21st century. One should not use it as a straw person. However, the prevailing theory fails to assess sufficiently the viability of other liability regimes that provided partial owner shielding. My feeling is that historical analyses of various liability regimes that were widely used in Period II – those that disappeared in the transition to Period III – can inspire the theoretical and policy discussion of alternatives to our present-day limited liability regime. They reinforce the case made by some economists and lawyers who have proposed alternatives to full limited liability for investment banks and the financial sector more generally in the wake of the crisis (e.g. Admati et al., Reference Admati, DeMarzo, Hellwig and Pfleiderer2018; Davidoff, Reference Davidoff2008; Goodhart and Lastra, Reference Goodhart and Lastra2019; Hill and Painter, Reference Hill and Painter2009).Footnote 29

We should continue this re-evaluation using the historical experience as one of the empirical and theoretical starting points. More empirical studies of Period II and the transition to Period III – comparing jurisdictions with different liability regimes, sectors with different liability regimes and the before-and-after of the introduction of a specific liability regime – can not only improve our understanding of the economic history and political economy of the 19th century but also take us a long way towards proposing a better economic theory, and comparative institutional analysis, of limited liability. History can expand our imagination in considering alternative liability regimes for different sectors and different types of corporations in the 21st century.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank David Gindis, for initiating this theme issue and for the advice and encouragement throughout this project, David Ciepley, Giussepe Dari-Mattiacci, Joshua Getzler, Assaf Hamdani, Ehud Kamar, Kobi Kastiel, Michael Lobban, Bruce Mann, Uriel Procaccia, Holger Spamann, David Skeel four anonymous reviewers and participants in the TAU corporate law forum and the Annual Conference of the European Association of Law and Economics for references, suggestions and comments. My thanks also to Mais Abdallah for the research assistance on this paper and Amanda Dale for her editing.