Beneath the dream of fame, another dream… of turning into a desirable and desired commodity.

Zygmunt Bauman (Reference Bauman2007:13)Introduction

A place name, written in large white capital letters, misaligned, and emplaced upon a hill: be it in Dubai, Ecuador, Ireland, Poland, or Sweden (Figure 1), we immediately recognize a citation of the HOLLYWOOD sign. Aligned unevenly on a steep hillside above Los Angeles, the nine 13.7-meter-high white block letters spelling ‘HOLLYWOOD’ eponymize the film industry and cult of celebrity that has gained a foothold in nearly every global market. Citations of this famous language object—found throughout the world, and far less famous—establish an intertextual and interdiscursive link to the enregistered source sign and its ever-changing historical, cultural, and socioeconomic context. But why is this process of enregisterment and citation being produced, and how is it achieved? What are the contextual and material affordances and constraints for these localized citational processes, and how do they affect the enregisterment of the HOLLYWOOD sign as a global emblem? When, if ever, is the process of emanation coming to an end, and we can no longer talk about HOLLYWOOD?

Figure 1. a. ‘Eastern Europeans have their own Hollywood sign’. Reddit, 5 October 2018; b. The YACHAY TECH sign in Ecuador. 27 January 2014, Agencia de Noticias ANDES, Creative Commons 2.0; c. The HATTA sign in Dubai Emirate, United Arab Emirates. Instagram post by @destinationmydubai; d. The HAMMARSTRAND sign in Ragunda Municipality, Sweden. 22 June 2011, Petey21, Creative Commons 1.0; e. The HOLLYWOOD sign in County Wicklow, Ireland. Instagram post by Visit Wicklow (@visitwicklow).Footnote 1

We address these questions by considering an international but limited sample of cases where the HOLLYWOOD sign is cited and emplaced in new settings. The sign has been cited and adapted in a myriad of ways, media, and contexts, perhaps especially in pop and consumer culture. To this, we can add the many appropriations of the name Hollywood and its indexicalization of film industry and fame for businesses and activities in other places (e.g. Bollywood, in India; Nollywood, in Nigeria; Trollywood, in Sweden; HollyŁódź, in Poland). In this article, we can but scratch the surface of this citational and intertextual reservoir: we include some replicas of the source sign in and beyond Hollywood but focus on HOLLYWOOD-esque signs found in other places. These other places include but are not limited to the locations where we reside, and where we have thus been able to observe and collect cases. In obtaining a more detailed understanding of how the studied semiotic processes are afforded by local political economy and social interaction, we draw upon an ongoing ethnographic project on the role of language in processes of urban change in Gothenburg, Sweden.Footnote 2

Our analysis of these cases begins with the introduction of the ‘original’ sign in Los Angeles and the historical process through which this language object was enregistered (Agha Reference Agha2006) and became—to paraphrase the late writer and critic Clive James—‘famous for being famous’. This context further illustrates that the HOLLYWOOD sign is an object of cultural value within a global hierarchy of popular cultural forms, and as such, carries a differentiated schema of value that locates its evaluators and the context of evaluation. Next, we seek to uncover the mechanics through which this language object is emulated, showing that the enregistered features of HOLLYWOOD are circulated via processes of citation (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2013). In the second part of the article, we shift our attention to the sign's semiotic features through a study of HOLLYWOOD-like signs beyond Hollywood, determining that size and emplacement, alignment and typography, lexical category, and color are all enregistered. This is followed by a discussion of tensions and ideological debates around two specific citations of HOLLYWOOD in the city of Gothenburg, Sweden: NYA HOVÅS and HISINGEN. We conclude with observations regarding the process we suggest calling diffuse citation, before reflecting more broadly on the prevalence of language objects in contemporary global society. Examining (what is likely) the world's most famous language object ultimately generates an understanding of how and why non-referential features of language objects in general are citable, and how this is conditioned by both political economy and ideology.

HOLLYWOOD: Sign, language object, and global emblem

The HOLLYWOOD sign is a language object, what Jaworski (Reference Jaworski2015:75) describes as ‘two- or three-dimensional pieces of writing… that do not serve any apparent informational or utilitarian purpose’. It is the transformation of language into an object, however, that enables the processes of citation and circulation—and the reproduction of exchange value tied to fame—that we analyze here. Understanding the role of language objects in these processes thus demands a political economy approach, drawing upon tools developed in social semiotics and linguistic anthropology. Following earlier findings that language plays a central role in the expansion of market capitalism (e.g. Cameron Reference Cameron2000; Heller Reference Heller2003), recent scholarship has shown that language objects have come to occupy a prominent place in the consumer culture of late capitalist societies. Through his study of Robert Indiana's public art sculpture LOVE, and subsequent productions of the word ‘love’ in a dizzying array of consumer goods, Jaworski (Reference Jaworski2015:91) argues that the proliferation of language objects in contemporary urban spaces reflect capitalism's power to commodify—and to ‘thingify’—otherwise intangible social exchanges, including affective stances, acts of conviviality, or strategies of democratization and conversationalisation (cf. Fairclough Reference Fairclough1992:222).

Taking on a variety of material forms, language objects are symbolic resources performing a sense of place, time, or person. Typically decorative or commemorative, language objects such as personal names on tattoos, jewelry, or written in the sand on the beach, can permanently or fleetingly manifest recognition, affection, or commitment to a person. As Järlehed (Reference Järlehed2015:179–80) further shows in the context of Basque Country and Galicia, language objects’ materialization of emotion can support not just consumerism, but the actualization of nationalist pride. Others observe that language objects feature prominently in processes of urban gentrification, such as Gonçalves (Reference Gonçalves2019:53) finds in the emplacement of Deborah Kass's YO/OY sculpture in Brooklyn's DUMBO neighborhood, and Theng (Reference Theng2021:6) notes in the predominance of neoliberal affect among the neon signage decorating upmarket cafes in Hong Kong and Singapore.

As a language object and symbolic resource, HOLLYWOOD has become ‘emblematically’ (Agha Reference Agha2006:235) associated with a set of values that facilitate its diffusion and spread into new contexts, domains, and genres. It is one of many global emblems,Footnote 3 examples of which are, among others, derived from art (e.g. the Mona Lisa), architecture (e.g. the Great Wall), and music (e.g. Vivaldi's Spring), all providing fodder for a bewildering array of interpretations, reproductions, and adaptations. Writing about perhaps the most renowned of global emblems, the Eiffel Tower, Barthes (Reference Barthes2012:131) observes that ‘the Tower is everything man [sic] puts into it… an inimitable object that is endlessly reproduced, it is a pure sign’. At turns lauded and despised by artists, poets, and cultural critics, the Tower assumed the role of ‘modernist visual icon’ (Conley Reference Conley2010:765; also see Insausti Reference Insausti, Homem and de Fátima Lambert2006) before evolving into ‘the Esperanto of tourism’ (Freeman Reference Freeman2016:118). Whether it is interpreted as a symbol of romance or a hallmark of sophisticated cultural cachet, likenesses of the Eiffel Tower are ubiquitous motifs, adorning t-shirts, accessories, advertisements, and handheld figurines, alongside nearly to-scale monuments in cities such as Macau, Hangzhou, and Las Vegas. The proliferation of such landmarks and souvenirs are indicative of an emblem's diffuse interpretations; as Löfgren (Reference Löfgren1999:88) writes, ‘There might be millions of tiny brass Eiffel Towers distributed over the globe, but no two of them carry the same meanings’.

Such flexible and idiosyncratic applications of meaning is a trait shared by global emblems. Guth (Reference Guth2012:29) traces the same capacity in Hokusai's Under the Wave off Kanagawa (1829–1833), which has been reproduced in such multitudinous contexts as to suggest what she calls the ‘dialectics of globalization’. Also known as The Great Wave, the famous woodcut is recognized as both emblematic of Japan and as a signifier of ‘local difference’ as it appears in everything from museum memorabilia to advertising (Figure 2). This meaning-making capacity, Guth argues, is ‘dependent on [The Great Wave's] status as a global icon’ (2012:29); when it was created, however, it was but one in a series of thirty-six woodcuts, and an unlikely candidate for global veneration. Similarly, the Eiffel Tower was erected for the 1889 World Fair, and was originally slated to be disassembled at the Fair's conclusion.

Figure 2. Three citations of Hokusai's Great Wave, from left to right: a coffee shop in suburban Hong Kong; a pair of socks for sale in New York City; the wave emoji on WhatsApp (photos by Sean P. Smith, 2021).

Neither the Eiffel Tower nor The Great Wave were produced with the intention of attaining globally emblematic status. Rather, emblematicity is a status acquired unpredictably and over time, a process that transpires through a complex interfacing of popular, administrative, and cultural actors (Lou Reference Lou2017:219). In the case of HOLLYWOOD, the sign was verging on falling down the mountain before its revitalization etched it rapidly into popular consciousness. At the time, the Hollywood film industry was already decades into its era of global dominance; the sign's valorization was in some ways merely a product of its adjacency to one of the world's largest cultural-industrial complexes, which delights in the occasional self-dedicated monument (e.g. La La Land, 2016). This extensive, only-sometimes-deliberate process of recognition involved myriad actors and economic forces before finally leading to the sign's metadiscursive uptake.

The sign did, however, begin with an outsized splash. Conceived as a billboard advertisement for a 1923 real estate development called ‘Hollywoodland’, the sign's letters—even larger than today's, costing the equivalent of a quarter-million US dollars—were lit by 4,000 twenty-watt bulbs, which in four separate bursts flashed ‘HOLLY’ – ‘WOOD’ – ‘LAND’ – ‘HOLLYWOODLAND’. Yet the first indication of the sign's future enregisterment came not with the billboard's cinematic grandiosity, but with the 1932 suicide of the actor Peg Entwistle, who allegedly jumped from the top of the ‘H’ to her death. The suicide and its subsequent reportage marked an initial, if grim, ‘symbolic’ perception of the sign (Braudy Reference Braudy2011:96) and the inaugural event in a ‘semiotic chain’ (Agha Reference Agha2006:205) of linked events through which the sign's enregistered meaning continues to circulate today (Figure 5b). The suicide availed the sign's potential for mediatization (Agha Reference Agha2011) as a news spectacle of Hollywood-worthy drama, and—with morbid fascination trained on the ‘H’—drew attention to the sign's materiality as a potential semiotic repertoire.

The sign's indexicalization of physical place lasted until 1949, when the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce furnished repairs in exchange for the ‘LAND’ being dropped. Thus decontexualized, the HOLLYWOOD's mediatized appearance in art and cinema in the 1960s and 70s exhibited alteration of the sign's qualia (Gal Reference Gal and Coupland2016:123; cf. Peirce Reference Peirce1955), or its distinctive physical characteristics. In the film Earthquake (1974), it was eponymously destroyed in its hilltop emplacement, and when inducted into pop art with Edward Ruscha's Hollywood (1968), it was emplaced on the crest of the hillside, rather than nestled mid-slope, to stress the horizontality of the name and sign and their likeness to the landscape. With his piece, Ruscha further altered one of the most distinctive enregistered features of the sign, its misalignment.Footnote 4 In 1976 Danny Finegood made the first alteration to the sign itself, when, arguing that the sign was an environmental sculpture, he draped banners to spell ‘HOLLYWeeD’ in celebration of relaxed marijuana possession laws (Nelson Reference Nelson2007). Two years later, the sign was rebuilt following a high-profile fundraiser, with the new letters constructed in the same font and alignment as the original sign and affixed with concrete and steel girders to ensure lasting perpetuity (Braudy Reference Braudy2011:169).

Today, the HOLLYWOOD sign is an essential and essentialized feature of the Los Angeles landscape, with countless visitors seeking physical or visual proximity to the sign itself. As place-name markers often assume importance when the context of their fame is otherwise ungraspable (Light Reference Light2014:145), glimpsing the HOLLYWOOD sign is a way of making the myth tangible, or even participating in it oneself. As Braudy (Reference Braudy2011:5–7) describes, visitors strive to see the sign and have their photograph taken with it as a means of acquiring an imprint of its ‘symbolic aura’, enhancing their own sense of ‘prestige’. Practices of seeing, photographing, and collecting the sign are motivated by the vast scale of HOLLYWOOD's mediatized representations, as tourists perform the hermeneutic circle by photographing that which they have already seen in images (Urry & Larsen Reference Urry and Larsen2011:179; also see Thurlow & Jaworski Reference Thurlow and Jaworski2014:240). At the Hollywood and Highland Center Mall in Los Angeles, visitors pay to use mounted binoculars to view the sign or pose at an angle at which their photograph may be taken with the sign visible in the distance (Figure 3a). Others embark on a well-trodden hike into the hills, where the sign may be framed clearly in the background or even glimpsed from above (Figure 3b). Much as with other iconic place names, there is a profusion of HOLLYWOOD in miniature reproduced as souvenirs (cf. Light Reference Light2014:142); whether in the form of postcards showcasing the sign (Figure 3c) or word-object figurines (Figure 3d; see Jaworski Reference Jaworski2010). The sign is still altered by individuals seeking ‘to publicize causes or just themselves’ (Braudy Reference Braudy2011:164); most recently, it briefly read ‘HOLLYBOOB’ in a 2021 protest against censorship restrictions on Instagram (Cole Reference Cole2021). This ongoing semiotic reconfiguration and adaptation of the language object in Los Angeles is the springboard from which HOLLYWOOD-esque signs appear around the world.

Figure 3. a. Viewing and taking photos with the HOLLYWOOD sign at the Hollywood and Highland Center Mall, Los Angeles, in 2013; b. Hiking up to see the HOLLYWOOD sign. Instagram post with user's identity redacted; screen grabbed 6 March 2021; c. HOLLYWOOD postcards at the Hollywood and Highland Center Mall, Los Angeles, 2013; d. HOLLYWOOD word-object souvenirs at the Hollywood and Highland Center Mall, Los Angeles, 2013 (all photos by Adam Jaworski).

The citation and circulation of an enregistered language object

This brief history of the HOLLYWOOD sign's emblematicity is indicative of what Agha (Reference Agha2006:80) calls a ‘sociohistorical process of enregisterment’, in which a semiotic repertoire becomes indexically associated with a set of cultural practices, identities, and/or values that circulate through time and space. Witnessed, photographed, and appearing in cinema and art, HOLLYWOOD has over the years given rise to an indexical field, or ‘a constellation of meanings that are ideologically linked’ (Eckert Reference Eckert2008:464) through an interrelated ‘coherence’ of signs (Jaffe Reference Jaffe2016:109). These meanings emerge less through spoken language than via the written indexical features of the famous place-name sign: its size, emplacement, alignment, typography, lexical category, and color—in other words, the enregistered qualia that support its widespread legibility in global social space. In this, HOLLYWOOD is perhaps merely the most widely recognized among many signs that have been shown to be enregistered within a given context (e.g. Järlehed Reference Järlehed2015; Jaworski Reference Jaworski2015; Järlehed & Fanni Reference Järlehed and Fanni2022; Zhou Reference Zhou2023). In each case, indexical coherence is achieved through the combination of qualia, or ‘bundling’: the ‘factor of co-presence’ that is inherent to all material things (Keane Reference Keane2003:414), and which ‘binds’ meaning (e.g. fame) to a material object (e.g. the HOLLYWOOD sign) and to the different semiotic features that constitute that object.

The sociohistorical enregisterment of bundled qualia predicates HOLLYWOOD's global circulation and appropriation, as the sign in Los Angeles continually ‘emanates’ as a source of semiotic and cultural value (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2013:346). HOLLYWOOD-esque signs appearing in disparate locations across Ecuador, Dubai, and Sweden are linked by a semiotic chain through which enregistered values are transmitted across spatiotemporal contexts in a process of ‘role alignment’ (Agha Reference Agha2006:203), as sign-making actors seek to establish association with schemas of cultural value through the citation of an enregistered semiotic repertoire. Yet more than simply reconstituting the HOLLYWOOD sign and its attendant value schema, actors orient to the sign's enregistered qualia to make new meanings. Following Nakassis (Reference Nakassis2013:54), we suggest that HOLLYWOOD is ‘cited’ by ‘reflexively’ animating select enregistered features in new signs while marking these signs as ‘not (quite)’ the same. Such consciously interdiscursive citational acts are deliberately ‘entangled’ with the preceding discourse event, as actors distinguish their voices through deploying some form of ‘quotation marks’ around the cited event while other elements are ‘deformed’ (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2016:25; cf. Butler Reference Butler1993:175). Citational acts are at once playful and delicate, as actors tap into the social power of a discourse event yet risk being perceived as sycophants if they fail to adequately distinguish their own voice. While the cited event may be ‘real’, its exact imitation is ‘fake’; a properly-executed citation, however, succeeds in being understood both as genuine and something new altogether (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2016:61).

The success or failure of a citation of HOLLYWOOD is mitigated by political economy, or the context-specific processes which govern the ‘valuation of resources’ and the systems through which resources are produced, circulated, and consumed (Del Percio, Flubacher, & Duchêne Reference Del Percio, Flubacher;, Duchêne, García, Flores and Spotti2017:55). Our attention to language objects necessarily entails focus upon the materiality and social semiotics of writing: both the form and enactment of text as a valued resource, access to which is determined by political-economic conditions. With Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu1984), Bauman & Briggs further observe that citations (what they gloss as ‘recontextualizations’) are selected through a ‘hierarchy of preference’ (Reference Bauman and Briggs1990:77) and are only successful in ‘competent’ performances, when the performer has access to the legitimized habitus. Authority within a political-economic system, in other words, is a typical precursor to legitimate citations. In the case of written text, legible writing is contingent on the availability, accessibility, and distribution of material goods and educational wherewithal (Blommaert Reference Blommaert2013:446). These factors are mitigated by a writer's socioeconomic background and the environment in which they write, structural conditions that, we add, are further articulated through gender, racialization, and sexuality. Citation-making ability is highly uneven, and within the public sphere there is continual struggle over whether citations are perceived as legitimate.

From this overview, we can make three observations regarding the citation of enregistered language objects. First, the enregisterment of written features affords significant possibilities for citation by other language objects. With ‘value-emanation’ proceeding through size, emplacement, typography, alignment, lexical category, and color, actors enjoy a certain accessibility for making competent or even semi-competent citations. Second, the materiality of language objects presents a notable constraint. In the case of sculptural place names (see Jaworski & Lee Reference Jaworski and Lee2019), the feature of emplacement is often contingent on the availability of a piece of land, which typically entails the possession of capital as well as the institutional legitimacy to erect an object in space viewable by the public. Sociopolitical hierarchies are often reproduced as the capital and institutional legitimacy required for the creation of language objects often tracks with hegemonic power. Third, while emanation may entrench symbolic power, the citation of language objects affords unique avenues in the circulation of value. While the land and materials for creating a ‘legitimate’ language object may elude most, competent citations can be circulated via informal and especially digital tools. Such semiosis may indeed be supported by alternative cultures of legitimacy, even shifting the values contained within the language object's enregistered features. Citation ‘opens up new discursive processes’ that are ‘constitutive of new ideological relations between actors’ (Thurlow & Jaworski Reference Thurlow and Jaworski2010:86), and these emergent relations may reinforce or subvert the dominant order which shaped an emblem in the first place.

When is the HOLLYWOOD sign? Deconstructing the bundling and hierarchization of enregistered features

As stated in the introduction, citations of HOLLYWOOD beyond Hollywood exhibit the enregistered multimodal features of size and emplacement, alignment and typography, lexical category, and color. Each token cites the source sign by a specific bracketing and quotation (cf. Nakassis Reference Nakassis2013), as well as a (re)materialization and bundling (cf. Keane Reference Keane2003) of its features mediated by local discourses, social interaction, and historical context. In the following two sections, we show how the when of HOLLYWOOD—in other words, when a sign is recognized as a token of the type—depends, first, on a historically and globally established hierarchy of the sign's enregistered features, and, second, on political-economic constraints and situational play with ‘intertextual gaps’ (Briggs & Bauman Reference Briggs and Bauman1992:149), or the perceived distance between an utterance (i.e. a language object) and a broader genre of discourse.

A systematic comparison of the signs in our sample suggests a hierarchical organization of the enregistered features; some features are more frequently activated than others, and hence seem more important for the bundling and citation of HOLLYWOOD. As illustrated by our sample of signs (see Table 1), color (white), letter case (upper case) and stroke (sans serif) are intimately associated with the source sign. These features are followed by lexical category (place name), and—with some more variation—size (large). The emplacement and typographic shape of the signs present considerably more variation and hence appear as less salient in HOLLYWOOD citations. Taking into consideration their local meaning-making potential, some of the enregistered features emerge as more important, thus indicating the operation of a parallel semiotic hierarchy. While it is the color, alignment, size, and emplacement that creates an aura of HOLLYWOOD, it is typically the play with lexical category and content that infuses a citation with additional local meaning. We can therefore divide the citations of the HOLLYWOOD sign into two large categories: language objects including the lexical item ‘Hollywood’ (and some but not all the other enregistered features, e.g. Figures 1a and 1e), and language objects that contain some of the features but replace the lexical content with another place name (the most common, e.g. Figures 1c and 1d) or even a different lexical category (less common, e.g. Figure 1b).

Table 1: Our sample of signs.

This further suggests that we need to take into account the distinction between name and lexical item, or signified and signifier: the name Hollywood travels along with the HOLLYWOOD citations both when they present other place names (e.g. NYA HOVÅS), and when they do not include a place-designating lexeme (e.g. ÄLSKA LIVET; ‘Love Life’). As Munn shows, a person's fame is the ‘product of transactional processes’ (Reference Munn1986:107) whereby the person's name travels ‘apart from his [sic] physical presence… through the minds and speech of others’ (1986:105). Similar processes are involved in the citation of HOLLYWOOD; the fame at the core of HOLLYWOOD's meaning potential travels through the name Hollywood, but also through the sign's enregistered features. Interestingly, when the materialization of the citation excludes the place-designating lexeme from the bundling, the name Hollywood is still part of the recontextualization process: it often materializes in spatiotemporal proximity to the citation, in co-texts such as metacommentary by the media and viewers of the sign by which the citation is characterized, as in ‘Hollywoodesque’ or (in Swedish) ‘Hollywood-skylten’.

What differentiates HOLLYWOOD from other global emblems is that it is a written word, a language object, and hence can be filled with varied lexical content. Although the prototypical HOLLYWOOD citation involves a place name like the source sign, not all do; other kinds of names and words are seen, such as Finegood's 1976 HOLLYWeeD and Johansson's 2006 JOHANSSON. Yet another dimension opens up when the citation includes a homonym with different meanings in different languages. The word hell is a (defamed) noun in English and a (famous) place name in Norwegian. The animators of the HELL sign near Trondheim in Norway consciously play with the semantic and grammatic ambiguity that is produced when this language object is lifted from the linguistic trapping of its national context and displayed and mediatized to international audiences where English dominates (Christenson Reference Christenson2021). While such atypical citations expand intertextual gaps, the authority of the sign (and its producer) is often preserved through discourses of creativity and/or transgression. Though the authority of Finegood's and Johansson's citations relies heavily on the artists’ own cultural capital (Jaworski Reference Jaworski, Coupland, Sarangi and Candlin2001; cf. Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984), equally important is the HOLLYWOOD sign's symbolic value and the dominant frame of tourism and place branding (cf. Jaffe Reference Jaffe2016, quoted above).

The JOHANSSON sign (Figure 4a), raised on a hill in Kumla in 2006, was framed as an art installation carrying the name ‘Untitled’ and played with the tension between fame and anonymity. Artist Peter Johansson's stated intention was to democratize the aura of the source sign and make it accessible to ‘everyone’ through elevating the surname Johansson, which, held by 275,000 Swedes, is the nation's most common (Nerikes Allehanda 2006). The anticipated democratization of fame, however, conflicted with the emanation of unparalleled fame from HOLLYWOOD and risked self-aggrandizement; in the end, the sign entered into a chain of mediatization that transformed it into a tourist site and place-branding tool. As interdiscursive language objects, such recontextualizations are embedded within the emblematic meanings of HOLLYWOOD irresponsive of an animator's initial intention. This indexical linkage is marshaled through the semiotic citation of the source sign's enregistered features, which we now examine in more detail.

Figure 4. a. Performing (Swedish) ‘everyone-ness’: A group of people with the surname Johansson in front of Peter Johansson's art piece, ‘Untitled’, popularly named ‘Johansson’ (photo by Rune Tapper; used with his permission);Footnote 5 b. The new place brand logo of Tidaholm (2020) as word sculpture with inspiration from both the HOLLYWOOD and the LOVE signs (photo by Marcus Andersson; source: Västgöta-Bladet, 8 May 2020; accessed 19 May 2021; used with permission).

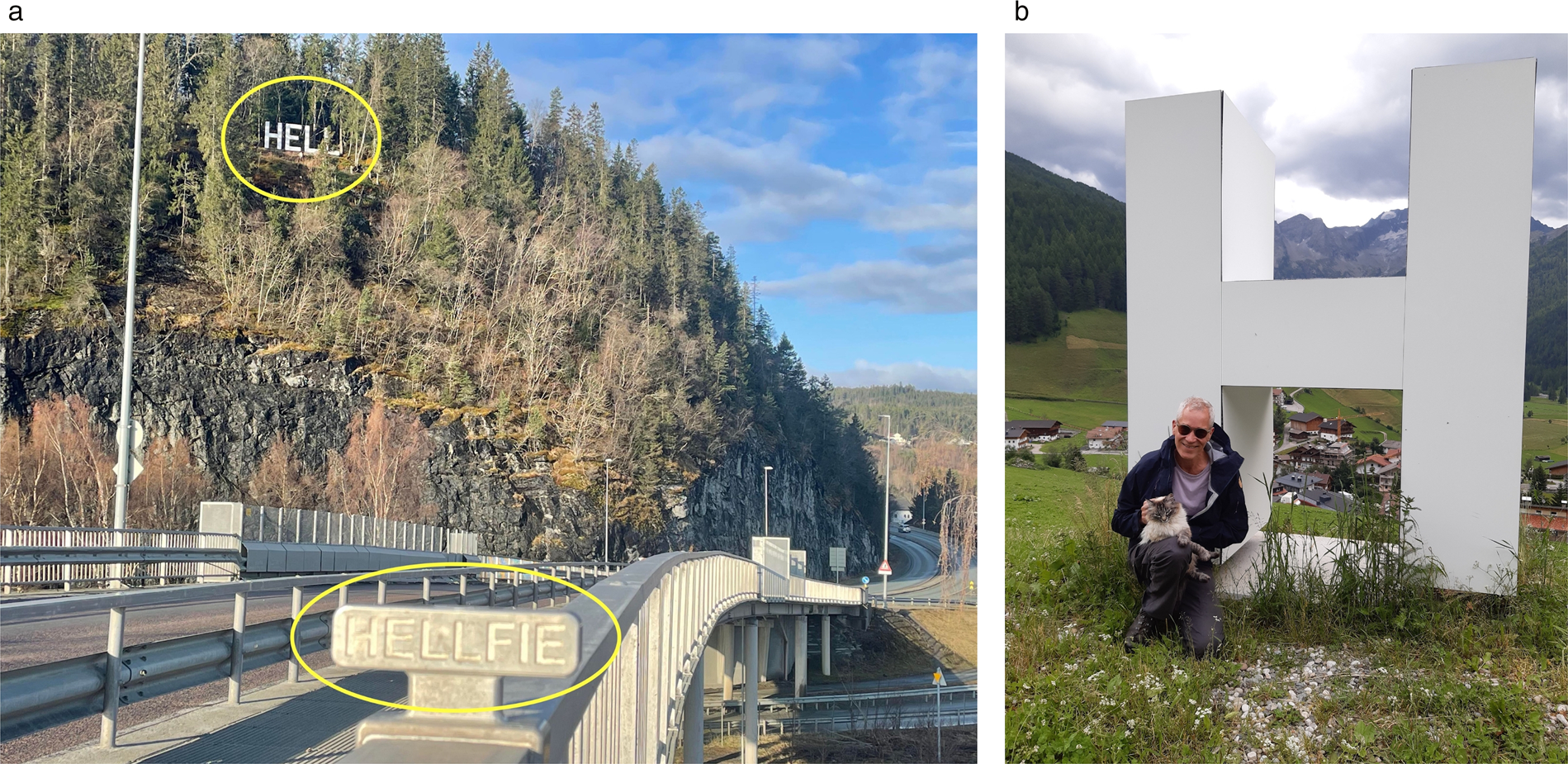

Figure 5. a. Wordplay sign ‘HELLFIE’ indicating where to take selfies with the HELL sign in the background (photo by Rune Sagen, 28 April 2023, used with his permission); b. Johan Järlehed posing in front of the H in Rein in Taufers, the second letter of the ‘BIG8’ Challenge, July 2023.

Apart from temporary (re)colorings of the HELL, OFFENBACH, and NYA HOVÅS signs (Figure 6 below), our examples use the clear white color of the source sign. By adding black and blue—the colors of German football team FSV Frankfurt—to six of the nine white letters of the OFFENBACH sign, the Frankfurt supporters performed a kind of triple quotation: they created a new offensive citation of the OFFENBACH ironic citation of the HOLLYWOOD sign while citing the tradition of alteration of the former for various social claims (Düncher Reference Düncher2019). As Jaworski & Lee (Reference Jaworski and Lee2019) contend, while white can enhance the visibility of signs in outdoor settings, ‘the connotations of whiteness with pure or pristine spaces of upmarket urban areas go hand in hand with their gentrifying, hence upwardly mobile aspirations’. Although not all of the signs analyzed in this article are emplaced in upmarket urban areas and entangled in gentrification processes, they are arguably all drawing upon HOLLYWOOD's ‘value-emanation’ (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2013:346) and thereby index aspiration, created in an effort to transcend the boundaries of an existing place, activity, or object and enhance its symbolic value.

Figure 6. a. One of the first signs of the exploitation of Nya Hovås: a ritual act of possession, February 2017; b. The colored NYA HOVÅS sign in August 2021 (photos by Johan Järlehed).

All but one sign in our sample, after all, is large. Measuring 68×8 meters, HAMMARSTRAND is even the largest place name sign in Europe,Footnote 6 almost as big as the HOLLYWOOD sign (90×13.7m). In general, the proposed and/or final emplacement of the signs on a hill follows the HOLLYWOOD model. There are, however, several cases where the sign is emplaced at ground level, generally by attaching the letters to a metal-concrete structure or slightly above ground level on another edifice. These signs are generally smaller, raised just above the heads of passerby. ‘Emplacement’ contributes to defining the social meaning potential of signs (Scollon & Wong Scollon Reference Scollon and Scollon2003; also see Androutsopoulos & Chowchong Reference Androutsopoulos and Chowchong2021), and this more human-scale emplacement is arguably driven by the increased potential for social interaction, mediatization, and participatory place branding. Language objects in public space invite members of the public to interact with the sign, climb or sit on it, and post photos on social media (Figure 4b; also see Jaworski Reference Jaworski2015; Gonçalves Reference Gonçalves2019; Jaworski & Lee Reference Jaworski and Lee2019). Posts are typically indexed with clear hashtags, reflecting institutional desire for attention, and are thus always engaged in processes of (re)mediatization. For instance, in the case of HELL, the animators continue playing with the name by creating the neologism HELLFIE, and even suggest where people can place themselves to take the best selfie with the citation in the background (Figure 5a).

Reprising the function of the original HOLLYWOODLAND sign, the HOLLYWOOD-esque signs in our sample contribute to the exploitation of the land on which they are emplaced (see more in the section on NYA HOVÅS below). The variable emplacement of such signs is facilitated by their generally metonymic and emblematic character, which ‘stand in for a place… rather than point to a particular location, they semioticise that location in the compressed form of a language sculpture (usually of its name)’ (Jaworski & Lee Reference Jaworski and Lee2019). HOLLYWOOD is copyrighted by the local Los Angeles municipality, yet notably it is not the word or font that is protected, but rather the ‘staggered arrangement’ of the letters (Braudy Reference Braudy2011:176). This legal regulation suggests that the feature of alignment is key for the successful citation of the HOLLYWOOD sign. This is further confirmed by our sample, where few signs are completely aligned (excepting e.g. KALMAR). Typographically, our examples display minimal intertextual gaps regarding letter case (with one possible exception, they all use uppercase), and stroke (all deploy sans serif). However, the majority are distanced from the source sign's square capitals with truncated edges and octagon-shaped closed counters. One reason why most HOLLYWOOD citations typographically deviate from the source sign may simply be that ‘it is difficult to produce such shapes’ (interview with Jesper Hallén, May 2021). Material affordances, in other words, contribute to intertextual gaps.

The discussion in this section underscores that, when analyzing the citation and circulation of language objects, the material affordances which attend HOLLYWOOD's bundling of writing features are as essential a consideration as socioeconomic dynamics. Much as Shankar & Cavanaugh (Reference Shankar, Cavanaugh, Cavanaugh and Shankar2017) conceptualize ‘language materiality’, the material and socioeconomic dimensions of language are complexly intertwined with and jointly condition processes of citation. In the remainder of the article, we focus on the socioeconomic dynamics of enregisterment and citation among language objects by a close inspection of two case studies. The analysis shows how actors who possess the requisite social, cultural, and economic capital can manipulate the enregistered features with considerable leeway, and thus mediate the when of HOLLYWOOD.

NYA HOVÅS vs. HISINGEN

In the next two subsections, we present further insights into the political-economic context of citation by investigating the two cases of HISINGEN and NYA HOVÅS in Gothenburg, Sweden. Even as the two signs present notional similarity, they differ in key ways that reflect the political economy of their respective contexts (see Table 2).

Table 2. Overview of key political-economic differences between the two signs.

NYA HOVÅS: Struggles over economic and cultural capital

Nya Hovås ‘New Hovås’ is the unofficial name of a new neighborhood that, in 2014, began construction 12km south of the Gothenburg city center. According to city authorities the formerly unexploited rural land is called Brottkärr or Brottkärrsmotet ‘Brottkärr junction’, yet developer Next Step Group did not find this designation marketable and contracted an agency, Löfgren Branding, to create a new name. The agency came up with Nya Hovås, intertextually referencing the sense of luxury associated with the well-known and prestigious Hovås neighborhood some 3km north of Nya Hovås (interview with Löfgren Branding, October 2017). The developer's choice, however, has not been officially approved and adopted by Gothenburg's Naming Committee (Järlehed, Löfdahl, Milani, Nielsen, & Rosendal 2021). Although the name Nya Hovås is widely recognized and used by the general public, it has yet to feature on any city signage.

In 2014, Next Step Group adopted HOLLYWOOD as the model for a large sign displaying the name NYA HOVÅS (Figure 6a). As a citational act, the sign was supposed to ‘stick out a little, to suggest cheekiness, world class’ (interview with Next Step Group, December 2017). Drawing attention to and up-scaling (Carr & Lempert Reference Carr and Lempert2016) what, until then, was a rather unknown area around the highway junction, we can further suggest that this re-naming can be read as a ‘ritual act of possession’ that converts ‘undifferentiated space into place’ (Tuan Reference Tuan1991:687). Here, the HOLLYWOOD citation performs such a ritual act by replacing the official place name with a new, commercial one. In addition to the ‘legal-political’ claims of possession, NYA HOVÅS—much like the crosses raised by early Christian colonizers—also carries ‘a religious-baptismal significance’ as the existing place (Brottkärrsmotet) is believed to ‘undergo a “new birth”’ (Tuan Reference Tuan1991:687). With the sign's emplacement, a new place was born (Nya Hovås), with new owners, dwellers, and socioeconomic structures. As this case suggests, the citation of HOLLYWOOD not only sustains its ‘value-emanation’ and the enregisterment of the sign's written features, but further enregisters the name-place-value nexus of new places. That is, the semiotic chain of HOLLYWOOD citations that replace ‘Hollywood’ with another place name further enregister HOLLYWOOD and its bundled qualia, while simultaneously enregistering the location and name of the new sign/citation's emplacement. Such placemaking is motivated by the aspiration for fame and the symbolic valuation and economic potential which follow it, and both the lexical and material indexicalization of HOLLYWOOD serve as an easy-to-use resource for this end.

Such citations are, of course, variously enabled and constrained by their emplacement (Scollon & Wong Scollon Reference Scollon and Scollon2003). Initially, Next Step Group did not apply for a building permit but simply erected NYA HOVÅS, arguing that ‘it's our land’ (interview with Next Step Group, December 2017). Next Step Group justified their position with the fact that the NYA HOVÅS sign had been placed upon, but not attached, to the ground and could therefore be used as a mobile place-maker, having indeed been relocated on three occasions between 2016–2022 (Järlehed et al. Reference Järlehed, Löfdahl, Milani, Nielsen;, Rosendal, Leibring, Mattfolk, Neumüller, Nyström and Pihl2021:82–83). Only in 2020, following pressure from the city planning office, did they apply for and receive a permit. Through the emplacement of the sign on the ground in the middle of the neighborhood, it serves as a daily claim of recognition of the ‘new’ name and place, and of legitimacy for the developers’ work and investments.

Inside the neighborhood itself, opinions on the sign vary and thus metadiscursively bracket the citation of HOLLYWOOD in different ways. A shopkeeper interviewed in May 2019 liked the sign, since ‘it makes you happy’ and functions as an emblem for the development. However, Löfgren Branding, the consultancy that created the development's name and initial slogan, believe the sign is ‘very ugly’ and would never have recommended it. According to their representatives, the NYA HOVÅS sign does not fit the highbrow branding strategy of the development, which is to be ‘an exclusive urban village’ (interview with Löfgren Branding, October 2017). Among the three interviewed residents, opinions were more muted (interviews May, June, and October 2021). One described the sign as ‘strange’, saying that it ‘makes you feel like you drive into a shopping mall’. One interviewer commented that it was the first thing he observed when moving into the neighborhood; it's ‘very silly’, he remarked. Another person called the sign ‘super silly’ and that she would ‘not cry if it disappeared’. However, after growing up in Hisingen (see below), she was in favor of the unrealized HISINGEN sign to help the area improve its ‘bad reputation’. Perhaps in an attempt to counter the prevailing criticism and ridicule, and to repair their own authority, in July 2021 the developers added color to the sign (Figure 6b). This bracketing and apparent extension of an intertextual gap made it—in the words of one resident—‘less Hollywood’ and ‘more Nya Hovås’. However, the citational work turned out to be a whim: since November 2021, the sign is again white (though, by December 2022, its edges are soiled by exhaust fumes, indexing a certain neglect).

The story of NYA HOVÅS is telling with regards to class conflict on the ground of the accumulation of cultural capital, as even the most ‘common words’ develop different values for speakers from different social classes as markers of difference (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1984:194). This may explain how a HOLLYWOOD-like sign found its way into Nya Hovås (or Brottkärrsmotet), and not, say, Linnéstaden—the gentrified and bourgeois inner-city neighborhood that was alluded to in the marketing of Nya Hovås—nor to Örgryte or Långedrag, elite residential areas outside of the city's historical center. In these contexts, HOLLYWOOD-esque signs are likely to be perceived as too middle-brow. Although the middle-brow connotations of NYA HOVÅS did not escape the attention of Löfgren Branding, it did not hinder the developer from erecting the sign, and (unintentionally) risking indexing its relative economic subordination vis-à-vis the economic bourgeoisie. Together with most HOLLYWOOD-esque signs in our sample, what NYA HOVÅS presents is a symbolic distance to Hollywood. This influences the way in which these citations respond to power: they are ‘relatively authority-less, slightly incompetent (or at least lowbrow) citations which clearly are designed to compensate for the lack of symbolic capital that is attached to the place’ (David Karlander, p.c.). In the next subsection, we discuss a case in which the would-be citation of a HOLLYWOOD-esque sign motivated by local residents’ pride and ambition leads to the unexpected proliferation of further, locally inflected citations.

HISINGEN: The emergence of a new source of emanation

Hisingen, an island constituting almost half of Gothenburg's area, is home to a quarter of the city's population. Although its demographic and socioeconomic makeup is rather mixed, Hisingen has historically been stigmatized and is still often portrayed as working class, poor, and afflicted by crime (Despotović & Thörn Reference Despotović and Thörn2015). To counter this negative public image, Hisingen native and graphic designer Jesper Hallén proposed raising a large sign with the island's name on the Ramberget Hill, facing the Gothenburg city center. He turned to HOLLYWOOD for inspiration (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Jesper Hallén posing with HISINGEN in front of HOLLYWOOD. Hisingsskylten's Facebook page, 8 October 2014.Footnote 7

The proposal began generating popular attention in 2014 with the launch of a Facebook site,Footnote 8 the merchandising of HISINGEN prints (Figure 8), and media coverage in the leading local newspaper, Göteborgs-Posten, a mediatization which presented HISINGEN as a humorous underdog project to inspire local pride in a (former) industrial and working-class part of town. The animators of HISINGEN made an official citizen proposal that was signed by more than 10,000 Gothenburg residents, yet despite this popular support—and contrary to events in Nya Hovås—the municipal authorities denied the project's realization. The citizen proposal for a sign composed of ten-meter-high letters was reviewed by the Municipal Board for Parks and Nature, which, after considering four locations, rejected the application on the grounds of cost, permanent damage to the hill, and interference with planned regeneration projects in the area (Park och Naturförvaltningen Reference Park och Naturförvaltningen2016). If HISINGEN were to be emplaced on Ramberget Hill, the Board argued, it would be obscured by the 245-meter-high Karlatornet, marketed as ‘Scandinavia's tallest building’.Footnote 9

Figure 8. The HISINGEN sign printed on T-shirts for sale at a Hisingen market, on a tote bag in New York, tattooed on a woman's arm, and as huge letter objects being transported by helicopters (hotos from the HISINGEN sign's Facebook account).Footnote 10

However, according to the animators of the HISINGEN sign (Antonsson & Hallén Reference Antonsson and Hallén2014), the high-rise Karlatornet is just another example of generic star architecture that could be built anywhere in the world. The HISINGEN sign, they argue, would ‘anchor the building in the place’. Even as HOLLYWOOD's global emblematicity might be seen to foster genericism, the lexical and semantic content of HISINGEN evidently charges the sign with a sense of place that is deeply embedded in local imaginaries. This can be seen in a feasibility study by the Municipal Board (Park och Naturförvaltningen Reference Park och Naturförvaltningen2016:3), which, negotiating the intended citational act and reflecting on its interdiscursivity, considered whether the sign might spell the city's name, ‘Göteborg’, rather than ‘Hisingen’. As HISINGEN could be perceived as ‘exclusionary’ and ‘not part of Gothenburg’, the Board maintained, erecting GÖTEBORG instead would be ‘inclusive’ and demonstrate ‘that even Hisingen is a part of Gothenburg’. Finally, the Board argued that GÖTEBORG could be part of the city's 400th centenary in 2021, and one of the economic and branding vehicles for the city. Designer Jesper Hallén disagreed, contending that GÖTEBORG would not be as ‘humorous and beautiful’ as HISINGEN. To him, the contrast between the fame of Hollywood and the rather rough image associated with Hisingen is key to the successful citation. Additionally, like Ruscha, Hallén noted the spatial qualities of the name—its ‘horizontalness’ (Braudy Reference Braudy2011:164), that is, its horizontal physical extension—and the visual similarity between HOLLYWOOD and HISINGEN, as opposed to HOLLYWOOD and GÖTEBORG.

While to date the HISINGEN sign remains unrealized, with no in situ sign on Ramberget Hill, the case illustrates how technology and media—in this case, online digital productions—enable new affordances for the citation of emblematic language objects. In lobbying for the sign's creation, animators began to playfully introduce HISINGEN into digital photomontages, including historical photos. One such historical photo was reproduced in 2014 on the Instagram account of the local newspaper GöteborgDirekt (Figure 9; see Antonsson & Hallén Reference Antonsson and Hallén2014). This ‘historical’ HISINGEN sign was said to have been destroyed in a fire in 1922, predating the sign in Hollywood and suggesting that HISINGEN was the original, or the ‘real thing’. Additionally, several other physical projects around Gothenburg (Figure 10) indicate that, rather than the project dissolving following the Board's denial, HISINGEN now constitutes a source of emanation in itself. In Hallén's words, the HISINGEN sign ‘does not have to exist, to exist’. With each new sign inspired by HISINGEN contributing to its enregisterement on a local scale, as well as citing and simultaneously warping the ‘original’ in Los Angeles, the interdiscursive circulation of HOLLYWOOD is thus shown to have a long reach indeed. Contrary to most other place-name-based citations of the source sign that we have examined, the social life of HISINGEN relies heavily on its mediatization and it still not being erected in its proposed place. This subversive context has led to the sign's enregisterment as a locally signifying language object, its value circulating through citations in physical, digital, and mobile emplacements.

Figure 9. The ‘original’ HISINGEN sign before its destruction in a fire in 1922. Tidningen Hisingen (Facebook), 20 October 2014.Footnote 11

Figure 10. 3D adaptations of the HISINGEN sign in Gothenburg, from left to right: a styrofoam sign made by Jesper Hallén and friends for the Lindholmen Street Food Market (photo by Per Wahlberg, Göteborgs-Posten 14 April 2018); Café Fluß, a popular bar and music scene with an air of DIY urban cool (photo by Johan Järlehed, 25 April 2021).

Comparing the cases of NYA HOVÅS and HISINGEN, we see how the different political economies of the two contexts produce a skeptical if not dismissive reading of NYA HOVÅS, while HISINGEN is broadly seen as a triumph of artistic irony. As Searle (Reference Searle and Davis1991:536) observes, irony only works insofar as an ‘utterance, if taken literally, is obviously grossly inappropriate to the situation’. In the case of NYA HOVÅS, the utterance is not only taken but delivered literally, as if the producers of the sign really believe that there is a symbolic likeness between Hollywood and Nya Hovås. In other words, NYA HOVÅS lacks ‘quotation marks’ (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2016:25)—and in failing to define its individuality by distancing itself from the ‘original’, it is perceived as a charlatan. HISINGEN, by contrast, succeeds through the proposition that it is not taken literally. Rather, the ironic suggestion of symbolic likeness between Hollywood and Hisingen makes a shrewd if playful comment on inequality, ‘deforming’ (cf. Butler Reference Butler1993) the meaning of HOLLYWOOD through a reversal of the pathways through which symbolic capital is accumulated. The social outcomes of citation can thus be seen as embedded within the workings of political economy, even as the value of the source of emanation remains consistent.

Conclusion: HOLLYWOOD ‘does not have to exist, to exist’

The HOLLYWOOD sign is probably the world's most famous language object. First erected as a real estate advertisement in 1923, over the course of the twentieth century the sign evolved into a metonym of the American film industry and, ultimately, a global emblem of glamor and high status itself. In tracing this history as a process of political-economic valorization, we describe how the features of this language object became enregistered. The size, emplacement, alignment, typeface, lexical content, and coloring of HOLLYWOOD each communicate the symbolic value represented by the sign, which remains a source of emanation that circulates across continents and contexts. From rural hillsides in Ireland to mountains outside Dubai, these enregistered features are invoked the world over through the bundling of features in language objects, advertisements, and art that cite HOLLYWOOD in bids for status or plays at irony. The diverse meanings and values created through such citations respond to the spatial, socioeconomic, and historical conditions of emplacement; as our two case studies demonstrate, citation follows idiosyncratic trajectories, responding to different affordances while subject to intensely ideological value judgements and debates.

This leaves us with the question of what happens when the citation of HOLLYWOOD is less overt. Take the example of a flyer advertising an academic lecture that displays the word ‘ENGLISH’ in block white letters, the undulating emplacement following Hong Kong Island's mountainous topography echoing HOLLYWOOD (Figure 11a). Towering over Hong Kong's emblematic skyline, the ‘Future of English’ in the city is communicated as an imposing inevitability, wherein the English language is marked as high-status and globally significant. Sponsored by the British Council, the lecture is perhaps an unexceptional language-ideological plea for the relevance of English in a former colony (cf. Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine and Gal2000), where the apparent citation of the source sign indexes a still-vaunted Anglosphere. Looking to another example from Hong Kong, a McDonald's advertisement on the side of a double-decker bus displays the Golden Arches emplaced atop skyscrapers (Figure 11b), integrating with the cityscape in a move reflecting corporate efforts to communicate locality (Aiello Reference Aiello, Johannessen and Van Leeuwen2017). Here, the citation draws on a single enregistered feature—emplacement—but to the same effect, endowing the fast-food chain with international star-power as it weaves a tapestry of logos throughout Hong Kong's cityscape.

Figure 11. a. Poster for an academic talk, Hong Kong, 2011; b. McDonald's advertisement with the Golden Arches emplaced in the cityscape, Hong Kong, 2007 (photos by Adam Jaworski).

Especially in this final example, the citation of HOLLYWOOD is sketchy at best; one might instead argue that McDonald's is simply orienting to the myriad electric billboards that crown Hong Kong's nighttime skyline. Even the tenuous invocation of enregistered emplacement, however, is not a coincidence but a form of ongoing entanglement—one in which indexicality breaks down into iconicity, as McDonald's the brand cites not the physical metonym of the American film industry, but rather a global ‘aesthetics of brandedness’ (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2016:81) that is collocated with that very metonym. Such citations, we argue, are diffuse: the citation of the source of emanation is not necessarily conscious nor explicit, yet through the select application of enregistered semiotic features, an interdiscursive relation with the symbolic value of a source event is nonetheless established. To put it otherwise, HOLLYWOOD ‘does not have to exist, to exist’.

Diffuse citation may aptly describe the circulation of a language object such as HOLLYWOOD, the features of which have become enregistered through political-economic valorization. Circulating globally, enregistered language features depart further and further from the source of emanation, as the contexts in which they are rebundled and rematerialized grow ever more various; rather than an endless procession of HOLLYWOOD signs and related language objects, we see the diffuse citation of a global linguistic-semiotic register that is consolidated through the repetition and uniformity of linguistic, visual, and design resources. In language objects, billboards, advertisements, art, and other texts-in-place, this register is applied broadly towards the accumulation of symbolic value—or parodies it, establishing ironic distance from the HOLLYWOOD sign. Yet as official sanction, institutional legitimacy, and social standing privilege citations enacted by prior holders of capital, this register is mitigated by the political-economic context in which it is manifested.

So long as the global diffusion of the linguistic-semiotic register derived from HOLLYWOOD remains interdiscursively entangled with the source sign in Los Angeles, the value-emanation of the sign that, as we write this, is still gazed upon in its seat atop Mount Lee continues to grow; with each new citation, HOLLYWOOD is enshrined and entrenched within social imaginaries the world over. Entanglement entails a mutual interrelation between output and imputation, and amid ongoing processes of mediation and mediatization, each come to anticipate the other. Like other forms of media, language objects are so eminently cite-able as to be intended for citation, in contexts ranging from the overt to the diffuse. This, perhaps, is one account for the global effervescence of language objects, as the late-capitalist bid to extract value out of every conceivable facet of social life can but replay the orthodoxies of the commodity (cf. Smith Reference Smith2021). And so, in a new copycat sign, a selfie, an impulse to point and say ‘Look!’, we see HOLLYWOOD everywhere—an endlessly repeated invocation of fame, of value itself.