Dear Editor,

The article entitled “Lightening up before death” by Macleod (Reference Macleod2009) captured our attention, as we observed the same phenomenon in 5 terminally ill patients in our home-based palliative care unit over approximately 3 years. All cases showed a similar clinical pattern reported by Macleod (Reference Macleod2009) and were classified by our team as patients experiencing an “energy surge” (ES).

The existing literature sparked our team’s interest in ES (Emanuel et al. Reference Emanuel, Ferris and von Gunten2010; Nahm et al. Reference Nahm, Greyson and Kelly2012; Schreiber and Bennett Reference Schreiber and Bennett2014; Wholihan Reference Wholihan2016), specifically the one published by Macleod (Reference Macleod2009), which led to a complete retrospective chart review of our cases to analyze relevant clinical information, medication use, and clinical status, during and after ES, for both patients and their caregivers.

ES, also coined as premortem surge, terminal lucidity, or terminal rally, is a deathbed experience reported as a sudden, inexplicable period of increased energy and enhanced mental clarity that can occur hours to days before death, varying in intensity and duration (Schreiber and Bennett Reference Schreiber and Bennett2014).

ES has not been extensively researched, and much of our current knowledge results from anecdotal evidence (Emanuel et al. Reference Emanuel, Ferris and von Gunten2010; Macleod Reference Macleod2009; Nahm et al. Reference Nahm, Greyson and Kelly2012). It seems that ES does not pose any suffering or distress for patients experiencing it (quite the opposite) but can disturb caregivers who at times may be confused and can experience feelings of uncertainty, unrealistic hope, anxiety, denial, and confusion.

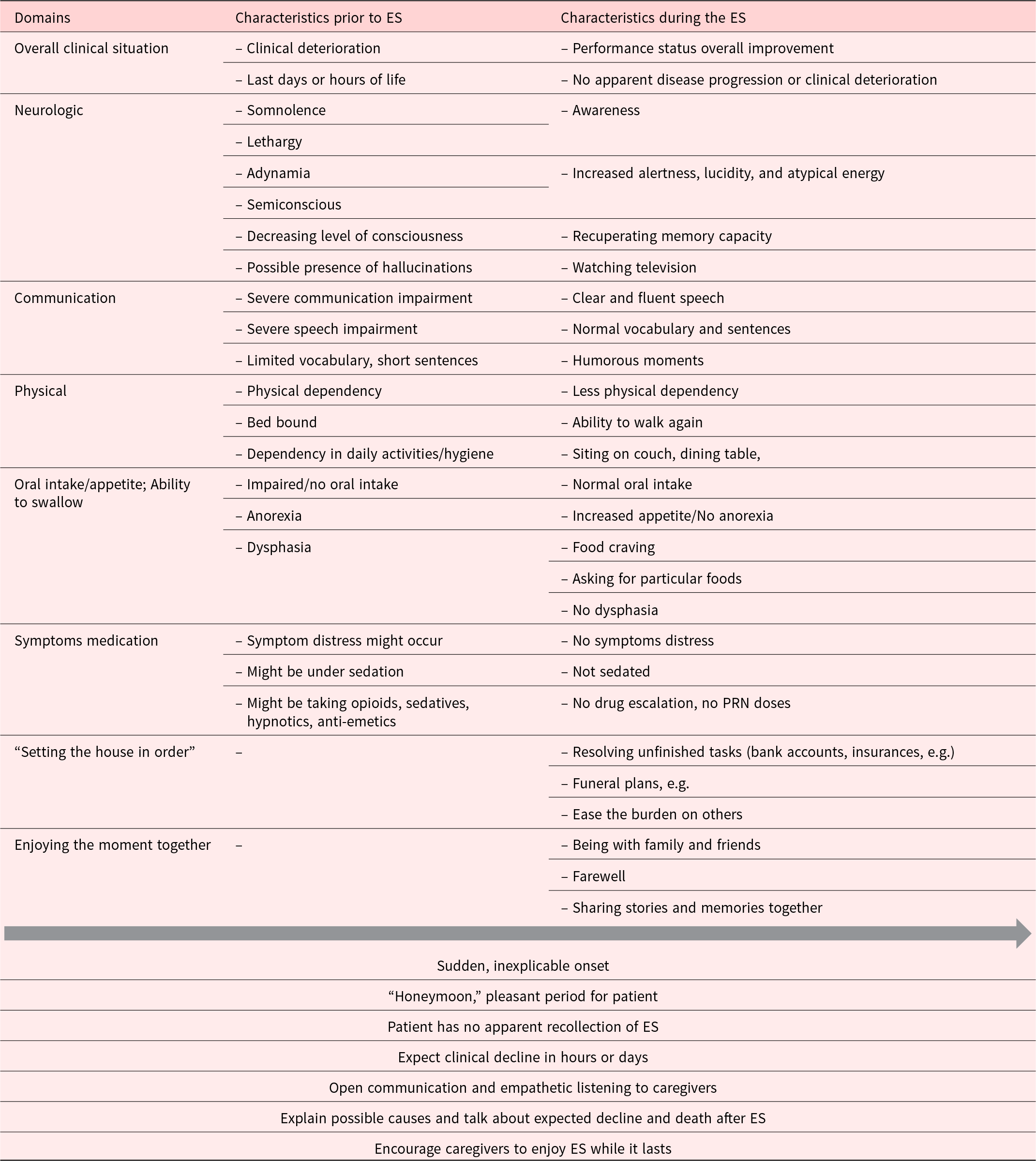

Although it might be scientifically relevant to investigate the underlying mechanisms leading to the phenomenon, it is most important to identify ES clinical patterns (Table 1) to help prevent caregivers’ unnecessary distress while caring for their loved ones during the end of life.

Table 1. Clinical pattern of energy surge based on observational data – a proposal

ES, energy surge; PRN; as needed.

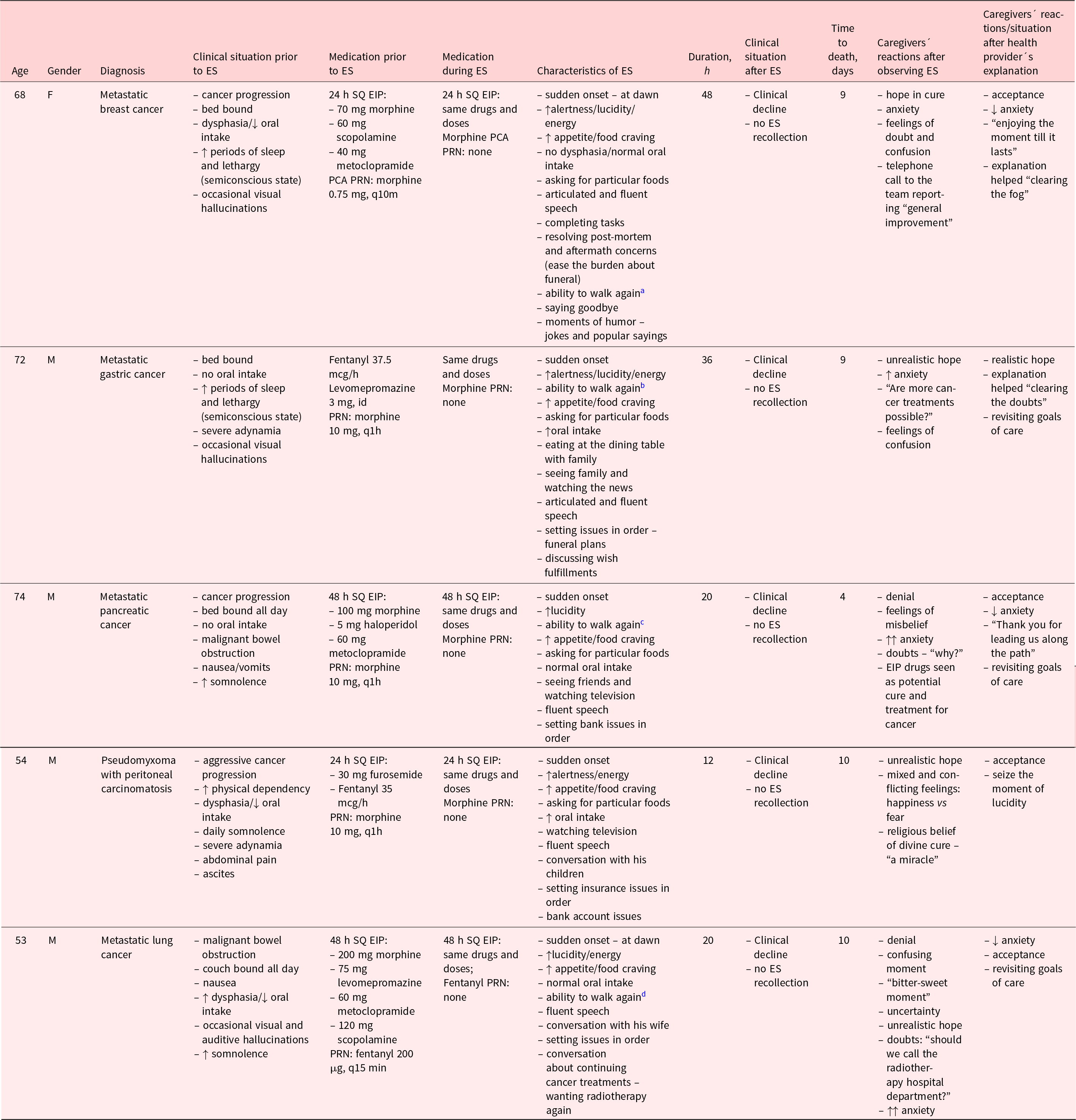

After analyzing our cases, we found that the prevalence of this event was low. As seen in Table 2, we discovered several common characteristics of the ES experience, as well as common reactions and feelings of caregivers.

Table 2. Characteristics of patients experiencing energy surge

EIP, elastomeric infusion pump; ES, energy surge; F, female; h, hours; id, once daily; M, male; m, minutes; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; PRN, as needed; SQ, subcutaneous.

↑, increased; ↓, decreased.

a From bed to the water closet.

b From bed to the dining room.

c From bed to the television room and sitting on the couch.

d From couch to the balcony.

All patients had advanced and progressing terminal illnesses, with significant physical and cognitive deterioration, decreased apetite and food intake, poor performance status, and dependency in daily care. Although patients were taking opioids and antipsychotics, such potentially sedative drugs did not inhibit patients’ awakening and lucidity. As also shown by Macleod (Reference Macleod2009), there appeared to be nothing particularly remarkable about the patients’ foreseeable clinical status or any particular triggering family event; in all patients, the onset was sudden (even during night/dawn), and no apparent prodromes or precipitating factors indicated that such a phenomenon would occur. It is noteworthy that in all cases, the same prescribed drug therapies were maintained, without dose escalation or additional PRN doses required. This reflects the so-called “honeymoon period,” with a stabilization of symptoms during ES. Heightened alertness, lucidity, and energy, accompanied by fluent and articulated speech with normal memory and mental abilities, are other common characteristics patients showed. Additional features of the ES were related to recuperating oral function and appetite. Food cravings for particular pleasant foods in normal quantities were frequently observed. Although patient mobility was impaired prior to ES, 5 patients regained the ability to walk, performed intimate personal care in the water closet, or sat on the couch or dining table with their family and friends. Another common feature was the ability to communicate clearly, to resolve unfinished tasks, and to “set the house in order,” thus alleviating caregiver after-death burden. After ES, all patients had a clinical decline and had no recollection of the event. ES tended to last an average 27 hours, and death occurred after an average of 8 days, which is in line with the literature (Wholihan Reference Wholihan2016).

The clinical implications of the phenomenon of ES are significant, since the event can have great impact on caregivers and family. ES allowed moments of memory sharing and farewell but only after the event was adequately explained to caregivers. Although loved ones appreciated ES as a pleasant experience and a “last gift” to enjoy, it was for most caregivers a distressing, alarming, and confusing period. In analyzing caregiver reactions and emotions after observing the unexpected energy burst of their loved ones, the initial reaction was distressing feelings of anxiety, doubt, and unrealistic hope. Open communication and empathic listening were essential in ameliorating caregivers’ confusing feelings, thoughts, and misbeliefs. Explaining the current knowledge on ES (although limited) was vital in reducing distress, confusion, and uncertainty, helping caregivers to put this experience into proper perspective and to appreciate this serene moment of sharing and saying goodbye.

In summary, identifying the patterns of ES and its common manifestations among the dying and openly communicating about the phenomenon can effectively reduce caregivers’ suffering and distress, offering the opportunity to embark on a shared and meaningful last journey.

Palliative care providers should be alert to the possibility of ES in their dying patients to intervene early with families and guide them gently and positively through this particular event. Providers should also carefully analyze ES events when they occur in order to add to the limited knowledge base around this unusual deathbed phenomenon. Our report can add preliminary observational data to help clinicians and their practice.

Funding

None declared.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.