1 Introduction

Over the past decade, Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk) has dramatically changed social science. The platform has freed researchers from reliance on the “narrow database” of social science undergraduates (Sears, Reference Sears1986) while reducing the cost and inconvenience of gathering original data (e.g., Berinsky et al., Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Casler et al., Reference Casler, Bickel and Hackett2013; Paolacco and Chandler, Reference Paolacco and Chandler2014). While respondents recruited on MTurk are not representative of the broader population, they are about as attentive as lab subjects (e.g., Mullinix et al., Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015; Hauser and Schwarz, Reference Hauser and Schwarz2016; Thomas and Clifford, Reference Thomas and Clifford2015) and exhibit the same cognitive biases as participants recruited through more traditional means (e.g., Paolacci et al., Reference Paolacci, Chandler and Ipeirotis2010; Horton et al., Reference Horton, Rand and Zeckhauser2011; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Cryer and Cheema2012). It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that treatment effects on MTurk tend to approximate those found in other convenience and population-representative samples (e.g., Mullinix et al., Reference Mullinix, Leeper, Druckman and Freese2015; Thomas and Clifford, Reference Thomas and Clifford2015).

The days of cheap, good data, however, may be coming to an end. Over the past few years, researchers have discovered that a non-trivial proportion of MTurk data is “suspicious,” generated either by “non-respondents” (bots) or non-serious respondents (e.g., Bai, Reference Bai2018; Dreyfuss, Reference Dreyfuss2018; Ryan, Reference Ryan2018). This poses problems for those who rely on MTurk for survey and experimental research. If bots or survey satisficers provide more or less random answers to survey questions, they could introduce noise that would bias treatment effect estimates toward zero.

We suspect, however, that threats to data quality on MTurk are potentially more grave. As we detail below, the nature of the platform offers Workers—participants, for social science purposes—unique incentives to misrepresent themselves and their attitudes, beliefs, and preferences. Moreover, existing signals of quality are likely upwardly biased, making it difficult for Requesters—in our case, researchers—to distinguish between more conscientious Workers and those attempting to game the system. This ambiguity also means that MTurk may be particularly attractive to internet trolls who can reap (minor) financial gains while engaging in the same kind of humorous or provocative behavior they exhibit elsewhere online. To the extent that insincere responding is correlated with other variables of interest—for example, belief in political misinformation (e.g., Lopez and Hillygus, Reference Lopez and Hillygus2018)—experimental treatment effects on such variables will be biased.

Spurred by these concerns, we fielded three original studies—one in August 2018 and two in the summer of 2020—to assess low-quality responding on MTurk and its impact on experimental results. To identify respondents masquerading as someone else, we used a Qualtrics plugin to record the IP addresses of the devices from which responses were filed. We further collected IP-level metadata, such as the estimated location of the device from which the survey was completed, to more closely examine responses. We also used survey completion times to identify potential survey satisficers. Finally, we included a battery designed to indirectly assess how many Workers engaged in “trolling”—that is, provided humorous or insincere responses to survey questions.

In our first survey, we found that 11 percent of respondents circumvented location requirements or used multiple devices to take the survey from the same IP address, while 16 percent of responses came from blacklisted IP addresses. Approximately 6 percent of respondents also engaged in trolling or satisficing. In all, when researchers first observed the data quality problem, about 25 percent of responses collected on MTurk appeared untrustworthy, a noteworthy uptick compared to studies conducted on the platform in 2015. While the rate of responses coming from suspicious or duplicated IP addresses fell between 2018 and 2020, according to our two additional studies, it remains three to five times higher than one would find on the least costly online survey panels (e.g., Dynata, Lucid). Even more troubling, the apparent prevalence of trolling on MTurk has tripled over the past few years.

Perhaps most importantly, we show that low-quality responses bias experimental results. Respondents who misrepresent themselves or troll differ from other survey-takers in how they respond to an experiment embedded in our June 2020 study. Specifically, they attenuate treatment effects—in our case by 28 percent—by introducing noise into the data. This suggests that researchers’ statistical power to detect effects is likely lower than implied by the observed n.

While we find relatively low response quality, researchers can preempt bad actors, most notably by restricting MTurk surveys to Workers with a long history of participation on MTurk. But tradeoffs exist: while data quality appears to improve significantly when we restrict surveys to Workers who have completed more than 1000 Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs), limiting participation in this way risks obtaining a sample comprised of Workers who may be overly familiar with surveys and who may be more subject to demand effects. Furthermore, the cost of conducting survey research on higher quality, centrally managed alternatives appears to be decreasing. As we show, samples recruited through Lucid (e.g., Coppock and McClellan, Reference Coppock and McClellan2019; Graham, Reference Graham2021, Reference Graham2020; Thompson and Busby, Reference Thompson and Busby2020) cost roughly the same per valid response than those recruited through MTurk. As such, we recommend that researchers employ a broader range of databases when recruiting respondents and use MTurk thoughtfully, primarily for quick tests and pilots. We conclude by offering a number of recommendations for maximizing data quality in these contexts.

2 Incentives for quality on MTurk

MTurk is a micro-task market: people complete HITs for small amounts of money. MTurk maintains ratings on all users, which means that both Requesters (employers) and Workers (participants) have incentives to behave: for Requesters, to fairly represent the nature of work being offered, pay a competitive wage, pay up promptly, and not withhold payments unjustly; for Workers, to submit high-quality work.

Incentives for quality, however, vary by how hard it is to observe quality (Akerlof, Reference Akerlof1970). Requesters, for instance, often cannot directly observe Workers’ demographic information or the location from which they are taking the survey, unlike survey sampling firms who recruit “panelists” based on such prior information. Workers plausibly exploit this opacity for gain. For example, foreign nationals might complete HITs limited to Americans because such HITs tend to be more lucrative, given differences in purchasing power parity. Workers may also create multiple accounts and complete the same HIT repeatedly, even when they are explicitly prohibited from completing each HIT more than once.

But these are just two examples—the problem is more general. MTurk was originally designed to be used internally at Amazon; humans performed simple classification tasks, like identifying patterns in images, that could not be automated (Pontin, Reference Pontin2007). Mechanical tasks like these and others have a correct answer, and Requesters can track Worker quality by checking performance on known-knowns periodically or by comparing how often Workers agree with the majority of their peers (e.g., Garz et al., Reference Garz, Sood, Stone and Wallace2018).

With surveys, however, quality is nearly impossible to observe. Most social scientists use MTurk to solicit Workers’ opinions, beliefs, and attitudes, which lack an external, objectively correct answer. This makes it difficult to parse genuine responses from insincere or inattentive ones. Except for cases in which a respondent takes extraordinarily little time to finish, researchers cannot accurately gauge whether or not participants are even reading the questions. Even selecting the first response option to multiple questions in a row is not conclusive evidence of satisficing (Krosnick et al., Reference Krosnick, Narayan and Smith1996; Vannette and Krosnick, Reference Vannette, Krosnick, Ie, Ngnoumen and Langer2014).

While the concern applies to all survey platforms, the problem is likely worse on MTurk. MTurk, unlike other online survey platforms, lacks a standing relationship between respondents and those who curate samples, which has two significant consequences. First, professionally managed survey platforms recruit respondents based on known characteristics, which naturally culls respondents who misrepresent themselves. Second, if the typical researcher uses MTurk two to three times a year, they have few incentives to sink resources into monitoring quality; instead, their investment is typically capped at the payout rate. On the other hand, survey vendors’ business model is based upon consistently providing high-quality data to clients. Since respondents take many surveys, these firms have opportunities to aggregate what might otherwise be individual weak signals into a more complete profile of respondent behavior which they can monitor. Participant monitoring that is not possible on MTurk—from recruitment through panel management—may incentivize respondents to behave more honestly.

When it comes to MTurk, the only signal of Worker quality that Requesters can send to the market is HIT approval—whether or not the Worker completed the task as assigned, which Amazon aggregates and tracks for each Worker. While HIT completion rates may prove a useful signal for researchers using the platform to assess Worker performance on objective tasks, the difficulty of judging the quality of survey responses may limit this metric's usefulness for social science research.

Worse, HIT completion rates themselves are likely upwardly biased, weakening any potential signal they send. Not only is spot-checking data for response quality time consuming for Requesters, but flagging false positives can hurt Requesters’ reputations and hence impose future costs. Workers who are denied a payment can retaliate against Requesters by posting negative reviews on sites like Turkopticon, which provides Workers with detailed information about Requesters’ average ratings and reviews of their HITs. Given these challenges—and the fact that the marginal cost of approving questionable work is typically a few cents—Requesters often batch approve completed HITs, making the HIT completion metric a biased signal of Worker quality.

This information asymmetry gives Workers incentives to misrepresent where they are located, use multiple accounts to “double dip,” and complete surveys insincerely or inattentively.Footnote 1 The difficulty in assessing response quality also means MTurk may be particularly attractive to people who enjoy trolling—that is, providing outrageous or misleading responses—as they can make money while indulging their id (e.g., Cornell et al., Reference Cornell, Klein, Konold and Huang2012; Robinson-Cimpian, Reference Robinson-Cimpian2014; Savin-Williams and Joyner, Reference Savin-Williams and Joyner2014; Lopez and Hillygus, Reference Lopez and Hillygus2018).

All of this suggests that data collected on MTurk may not be of the quality researchers often assume.Footnote 2 There are distinct incentives for Workers to misrepresent themselves, and existing signals of Worker quality may not capture the degree to which Workers engage in bad behavior. Consequently, bad actors may be far more common than is typically assumed. Moreover, these incentives may lead to further deterioration of data quality on the platform over time. Just as “bad money drives out good,” Gresham's law suggests that dishonest behavior from Workers may become the norm on MTurk, as there are few incentives for Workers to respond sincerely when satisficing, trolling, speeding through surveys, and circumventing location requirements saves them time and increases their profits.

Regardless of future trends, low-quality responding presents serious problems for social scientists using MTurk data now. Failing to exclude low-quality responses from MTurk data provides misleading estimates of scale reliability and introduces spurious associations between measures (Chandler et al., Reference Chandler, Sisso and Shapiro2020). As we detail below, low-quality responses are also liable to introduce significant noise into the data, not only reducing statistical power but also attenuating experimental treatment effects. For these reasons, understanding just how common the problem of low-quality responding on MTurk is can greatly improve the quality of inferences that scientists draw from MTurk data.

3 Assessing the quality of responses on MTurk

After becoming aware of the potential “bot” problem, we posted a survey on MTurk on August 17, 2018, advertising the HIT as “30 short questions on various topics on education, learning, and American society.” We solicited 2,000 responses from MTurk Workers located in the United States. Workers were told the survey would take about 10 minutes to complete, and we paid 60 cents for each completed HIT. In keeping with best practices (Peer et al., Reference Peer, Vosgerau and Acquisti2014)—and, thus, consistent practices, for external validity—we restricted participation to MTurk Workers with a HIT completion rate of at least 95 percent.Footnote 3

First, to assess how many Workers use form-filling software or bots to complete surveys quickly, we used No CAPTCHA reCAPTCHA (Shet, Reference Shet2014), which uses mouse movements to estimate whether activity on the screen is produced by a human or a computer program. Second, to identify people who masquerade as someone else or provide misleading data regarding the location from which they are taking the survey, we exploited data on IP addresses. First, we used a built-in Qualtrics plugin to collect respondents’ IP addresses. We then used Know Your IP (Laohaprapanon and Sood, Reference Laohaprapanon and Sood2018), which provides a simple interface to pull data on IP addresses from multiple services. In particular, Know Your IP uses MaxMind (MaxMind, 2006), the largest, most trusted provider of geoIP data, to provide locations of IP addresses. Know Your IP also collects data on blacklisted IP addresses, which often appear on the same traffic anonymization services that people use to evade location filters.Footnote 4 Know Your IP pulls blacklist data from ipvoid.com, which collates data from 96 separate blacklists.Footnote 5

We also collected information about how many responses originated from the same IP address. This information is useful because only devices that share the same router—or Virtual Private Network/Virtual Private Server—can have the same IP address. At minimum, this tells us how many responses originate from the same organization or household or which IPs used traffic anonymization software. Multiple HITs completed from the same IP address could reflect participation from several individuals (such as members of a family or residents of the same college dorm), but given current incentive structures, we suspect at least some of these data points reflect cases where individuals used multiple accounts to complete the same HIT more than once.Footnote 6

While we cannot identify all survey satisficers, one might reasonably assert that Workers who completed the survey extraordinarily quickly may not have provided meaningful responses. To that end, we recorded and examined response times. The median completion time was 573 seconds—or 9 minutes and 33 seconds, 27 seconds under the 10 minute target we provided. We flagged respondents as outliers if they finished 167 percent outside the interquartile range (IQR) of completion times.

To identify “trolls” and other non-serious respondents, we followed Lopez and Hillygus (Reference Lopez and Hillygus2018) in asking a series of “low incidence screener” questions about rare afflictions, behaviors, and traits (Cornell et al., Reference Cornell, Klein, Konold and Huang2012; Robinson-Cimpian, Reference Robinson-Cimpian2014; Savin-Williams and Joyner, Reference Savin-Williams and Joyner2014). Specifically, we asked respondents whether they or an immediate family member belonged to a gang, whether they had an artificial limb, whether they were blind or had impaired vision, and whether they had a hearing impairment. We also asked respondents how much they slept. We coded anyone reporting sleeping for more than 10 hours or fewer than 4 hours as unusual. In keeping with previous research, we flagged respondents as satisficing or trolling if they provided affirmative answers to two or more of these items (Lopez and Hillygus, Reference Lopez and Hillygus2018).Footnote 7 At the end of the survey, we also asked respondents an explicit question about how sincerely they respond to surveys. We compare responses to this question with responses to the screener questions to assess respondent honesty. (For detailed question wording, see SI 2.)

3.1 Study 1 results

We start by looking at evidence for the use of bots. All respondents who were asked to confirm that they were human using NoCaptcha ReCaptcha passed. This suggests that concerns about a “bot panic” (Dreyfuss, Reference Dreyfuss2018) on MTurk may be overwrought. However, this is all the good news we have; the rest of the data make for grim reading.

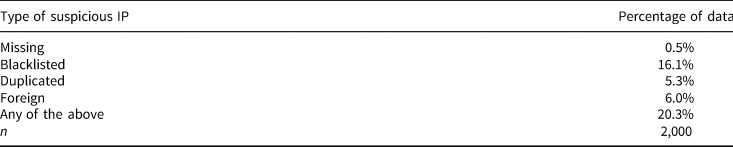

Of the 2,000 responses, the Qualtrics plugin recorded the IP addresses of 1,991 responses.Footnote 8 (We consider the nine responses for which Qualtrics could not record the IP address as suspect.) Of the 1,991 responses, approximately 5 percent came from an IP that appears in our dataset more than once (see Table 1). As noted previously, this could be because multiple people in the same household completed the HIT, but the more plausible explanation is that respondents used multiple accounts to complete the HIT multiple times.Footnote 9

Table 1. Frequency of different types of suspicious IPs, Study 1

A large majority of responses (94 percent) originated from within the United States (see Table 1). Of the 125 foreign responses, roughly a third were from Venezuela and an additional 13.6 percent were from India. (See Table SI 1.2 for a complete distribution of countries from which HITs were completed.) We suspect that these 125 responses are from MTurk Worker accounts that were created using US credit cards but belong to people living in other countries. It is plausible that the foreign IP addresses represent Americans who are currently traveling, but the geographic distribution of the IP addresses suggests this is unlikely. Similarly, the distribution of cities from which responses were filed suggests irregularities consistent with Kennedy et al. (Reference Kennedy, Clifford, Burleigh, Waggoner and Jewell2018) and Ryan (Reference Ryan2018) (see Table SI 1.3). Yet more shockingly, of the responses with recorded IP addresses, 16 percent come from blacklisted IPs. In all, around 20 percent of the sample came from outside the United States, blacklisted IP addresses, duplicate IPs, or missing IPs. We also examined how many Workers may have engaged in satisficing when completing the survey. We found that just over 2 percent of respondents were “fast outliers” who completed the survey in under 245 seconds. Consistent with folk wisdom, far more respondents (11.7 percent) were classified as “slow outliers.”Footnote 10

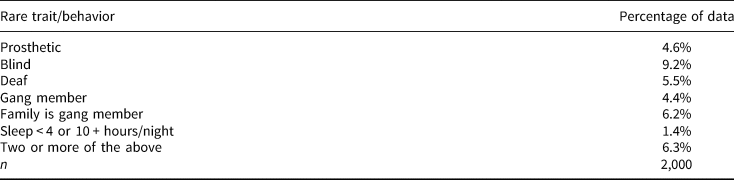

Next, we examined the frequency of insincere or inattentive respondents. Just over 9 percent of respondents in our data report being blind or having a visual impairment (see Table 2). Another 5.5 percent report being deaf. These numbers are nearly three and 14.5 times their respective rates in the population.Footnote 11 These large deviations from the national norm are possible but unlikely. Questions on gang membership have similarly implausible numbers (National Gang Intelligence Center (US) 2012). To be cautious, however, we only flag a respondent as trolling if they answered “yes” to two or more on such items. (See Figure SI 1.2 for the distribution of affirmative responses to these questions across all studies.) In all, we classify roughly 6 percent of respondents as likely “trolls.”

Table 2. Frequency of rare behaviors/traits, Study 1

Additionally, roughly 9 percent of respondents reported that they “always” or “almost always” provide humorous or insincere responses to survey questions. These respondents were more likely to be classified as trolls, suggesting that the low-incidence screeners identify insincere responding and not just inattentiveness. Of those who responded affirmatively to one or fewer low-incidence screeners, nearly 93 percent reported that they “never” or “rarely” answered humorously or insincerely. By contrast, roughly 58 percent of the 125 classified as trolls said that they usually answered sincerely (χ2 = 166.2, p < 0.001). In all, about 6 percent of Workers recruited for this study potentially responded insincerely.

To assess associations between measures of low-quality responding, we compare flagged IP addresses to Workers flagged as likely “trolls.” Thirty eight (38) of the 406 responses from “bad” IP addresses (about 9 percent of the sample) replied affirmatively to two or more of these items, compared to a rate of 5.5 percent among non-suspicious IP addresses. This difference is statistically significant (p < 0.05) but not immense. But neither did we expect it to be: people who game the MTurk system want to do enough to get paid while flying under Amazon's radar. Whether we want data from these actors, however, is another question.

Surprisingly, we find that, on average, potential trolls and responses from questionable IP addresses take significantly longer to finish (by 166 seconds, ${\rm p}< {0}.001$![]() ) and are significantly more likely to be slow outliers ($\hat {\beta } = 0.14$

) and are significantly more likely to be slow outliers ($\hat {\beta } = 0.14$![]() , ${\rm p}< {0}.001$

, ${\rm p}< {0}.001$![]() ). On the other hand, they are no less likely to be fast outliers ($\hat {\beta } = -0.00$

). On the other hand, they are no less likely to be fast outliers ($\hat {\beta } = -0.00$![]() , ${\rm p} = {0}.69$

, ${\rm p} = {0}.69$![]() ). We therefore do not count fast outliers as untrustworthy responses. And, as we show in SI 1.5, unlike other flagged respondents, speedsters do not appear to provide lower-quality data.

). We therefore do not count fast outliers as untrustworthy responses. And, as we show in SI 1.5, unlike other flagged respondents, speedsters do not appear to provide lower-quality data.

In all, about 25 percent of responses are from IPs that are duplicated, located in a foreign country, or blacklisted, or come from respondents who provided affirmative answers to two or more of the low-incidence questions. Altogether, nearly a quarter of responses are potentially untrustworthy.Footnote 12

3.2 Results from studies 2 and 3

One hopeful possibility is that data quality on MTurk was uniquely bad in 2018. That is, the problem may have been detected when data quality fell noticeably, and the collective response (e.g., Amazon Mechanical Turk, 2019a, 2019b) restored data quality to previous levels. To revisit the question, we fielded two new surveys in the summer of 2020. In June, we paid respondents (${n} = 1,\!503$![]() ) 75 cents to complete a 15-minute survey (Study 2), which included an experiment (detailed in Section 5), the noCAPTCHA reCAPTCHA qualification (again, all respondents passed), and the low-incidence screener battery, among other items. In July, we paid respondents (n = 409) 35 cents to complete a 5-minute survey (Study 3) with relatively little content aside from noCAPTCHA reCAPTCHA (again, all passed) and items to assess data quality. Importantly, to determine the efficacy of HIT approval rates for parsing bad actors from the rest, we restricted Study 3 to Workers with a 95 percent or higher HIT approval rate but did not do so for Study 2.

) 75 cents to complete a 15-minute survey (Study 2), which included an experiment (detailed in Section 5), the noCAPTCHA reCAPTCHA qualification (again, all respondents passed), and the low-incidence screener battery, among other items. In July, we paid respondents (n = 409) 35 cents to complete a 5-minute survey (Study 3) with relatively little content aside from noCAPTCHA reCAPTCHA (again, all passed) and items to assess data quality. Importantly, to determine the efficacy of HIT approval rates for parsing bad actors from the rest, we restricted Study 3 to Workers with a 95 percent or higher HIT approval rate but did not do so for Study 2.

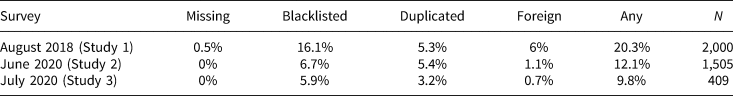

Table 3 demonstrates that the number of responses from suspicious IP addresses has changed substantially between 2018 and 2020. Using the most apt comparison—Study 3, which imposed the same qualification restrictions as Study 1—we see a marked reduction in the proportions of responses originating from blacklisted, foreign, or duplicate IP addresses. In particular, the proportions of blacklisted and foreign IP addresses found in Study 3 fell by more than a third and by roughly 90 percent, respectively, compared to Study 1. In total, about 10 percent of the data in July 2020 originated from suspicious IP addresses compared to about 20 percent in August 2018. Even Study 2, which did not impose restrictions based on HIT approval rates, received substantially fewer responses from blacklisted, foreign, and duplicate IPs than the 2018 survey.Footnote 13

Table 3. Frequency of different types of suspicious IPs

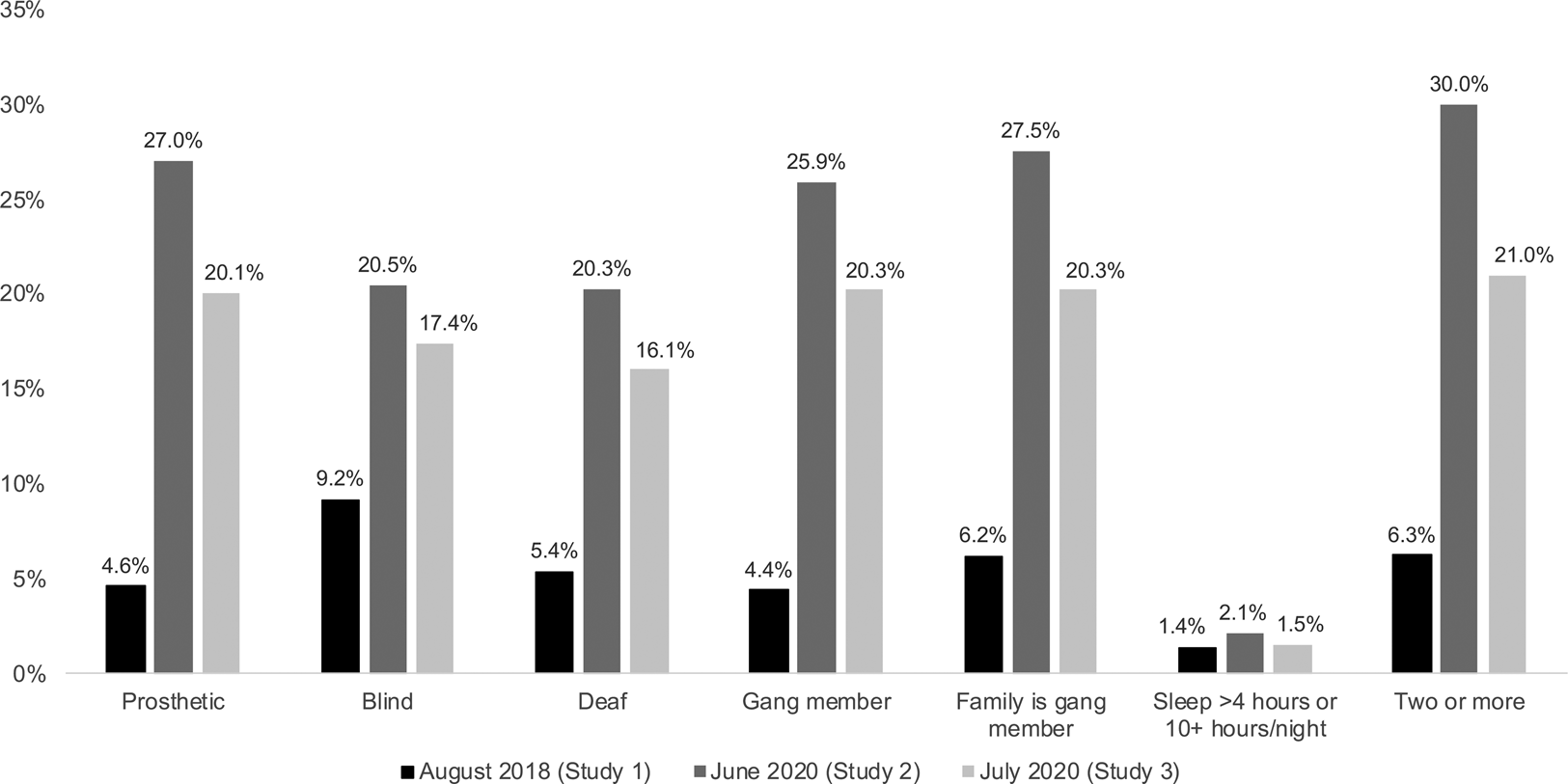

But any reductions in responses originating from suspicious IP addresses are offset by increases in humorous or insincere responding. These changes over time are cataloged in Figure 1. Whereas approximately 6 percent of the 2018 sample reported having two or more uncommon traits or engaging in two or more suspect behaviors, 21 percent of survey takers did the same in July 2020 (and 30 percent of the unrestricted sampled did so in June). Just under 5 percent of respondents in 2018 claimed to use a prosthetic; this rose to 20 percent in 2020 (and to 27 percent with less stringent respondent restrictions). A similar proportion of respondents claimed gang membership, while just 6 percent did so in 2018. And, as further evidence that at least some of this uptick is due to trolling and not just inattentive responding, over 14 percent of both 2020 samples admitted to responding inaccurately and humorously on surveys, compared to 8.8 percent in 2018. So while there may be fewer foreign respondents to add noise to the data, there appear to be significantly more insincere respondents. Crucially, with greater potential to produce systematic error, trolls may do more damage to survey quality than those who respond randomly.

Figure 1. Frequency of rare behaviors/traits across three studies. Note: Studies 1 and 3 imposed a 95 percent HIT completion rate restriction; Study 2 did not.

Additionally, evidence from the 2020 surveys suggests that there may be more foreign respondents than we estimate based on IP address data alone. Namely, both surveys included a new item designed to detect responses that potentially originate outside the US. One unique US convention is how the date is written: nearly all other countries use DD/MM/YYYY as a shorthand format, while the U.S. uses MM/DD/YYYY. We asked respondents the following:

Please write today's date in the text box below. Be sure to type it using the following format: 00/00/0000.

Approximately 17 percent of responses to this item in our July survey (Study 3) were written in the format DD/MM/YYYY, a number that rises to 20 percent in our June survey (Study 2) without the HIT approval rate qualification. In addition to dates that were written in the DD/MM/YYYY, we found that an additional 4.2 percent of respondents in Study 3 and 4.9 percent of respondents in Study 2 did not write anything resembling a date in the allotted space. This suggests that these are respondents who are taking the survey inattentively.

What explains the high proportions of survey takers who wrote the date in a format uncommonly used in the U.S.? Two major possibilities exist. One is that foreign respondents are able to use a VPN service to circumvent Amazon's location filter, appearing to have taken the survey in the U.S. when it was taken from a location outside the country. Another is that a disproportionate number of MTurk Workers in the U.S. are immigrants who retain their original date-writing custom.Footnote 14

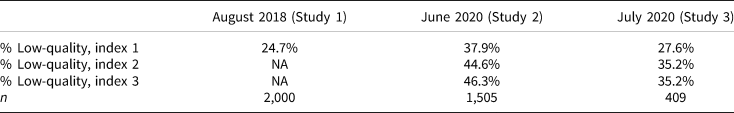

Unfortunately for scholars of American politics, we cannot parse these possibilities. That being said, this survey item does allow us to put an “upper bound” on our estimates of undesirable responses. Table 4 provides more clarity about the overall frequency of low-quality responses in our data using different metrics based on the information described above. The “lower bound” of low-quality responses, classified as % Low-quality, index 1 in the table, is based on our original definition of “low quality”: it includes the proportion of responses that either originated from suspicious IP addresses or were flagged as potential trolls by having answered in the affirmative to two or more low-incidence screener questions. % Low-quality, index 2 includes the former two qualifications but also adds in any respondents who wrote a date in the DD/MM/YYYY format. Finally, % Low-quality, index 3 gives us an “upper bound” on our estimate of low-quality responses by including aforementioned qualifications and any additional responses that did not provide a date when asked to do so.

Table 4. Estimates of low-quality responding using various thresholds

Note: Studies 1 and 3 imposed a 95% HIT completion rate restriction; Study 2 did not.

% Low-quality, index 1 includes suspicious IPs and incidences of trolling (per low-incidence screener measures); % Low-quality, index 2 includes suspicious IPs, incidences of trolling, and incidences of the date written in the DD/MM/YYYY format; % Low-quality, index 3 includes suspicious IPs, incidences of trolling, incidences of the date written in DD/MM/YYYY format, and any non-date entered into the open-ended date question.

These results suggest that large proportions of data collected on MTurk are of low-quality. About 25 percent of responses in Study 1 (conducted in August 2018) originated from suspicious IP addresses or were flagged as potential trolls; two years later (in Study 3), the proportion of responses flagged according to the same criteria was about 27 percent. While this may not be much of an increase, as discussed previously, these data belie the fact that the number of suspicious IP addresses on MTurk has decreased while estimates of trolling have increased by nearly fourfold (see Figure 1). When including other responses that used the DD/MM/YYYY format or answered our date question nonsensically, our estimate of low-quality responses increases to roughly 35 percent.Footnote 15 Both of these studies required Workers to have at least a 95 percent HIT completion rate, and this qualification requirement makes a difference in the proportion of low-quality responses. Without the qualification requirement, roughly 38 percent of the data in Study 2 originated from suspicious IP addresses or from potential trolls. When we add in those respondents who did not answer the date question according to directions (or in the conventional U.S. format), our estimate of low-quality responses jumps to nearly 50 percent. In sum, the proportion of low-quality data on MTurk ranges between 25and 50 percent, depending on the qualification requirements (based on HIT approval rate) imposed.

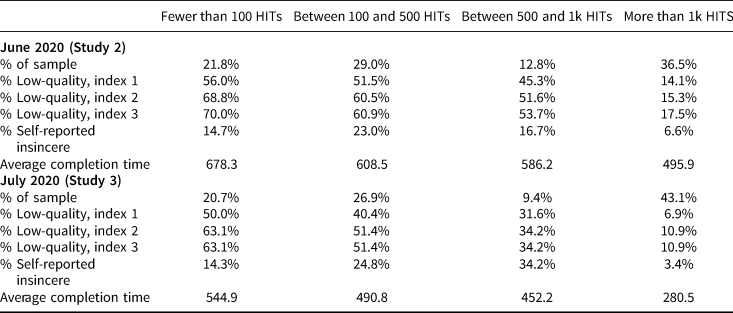

While these figures are troubling, perhaps the prevalence of low-quality responding can be reduced by requiring Workers to complete at least 5,000 HITs, as Amazon now recommends (Amazon Mechanical Turk, 2019b). In our 2020 surveys, we asked respondents to review their MTurk Worker account page and report the rough number of HITs they had completed.Footnote 16 In Table 5, we parse low-quality responses by the reported number of completed HITs. Indeed, data quality appears significantly better among Workers with at least 1,000 completed HITs. Our “upper bound” of bad actors topped out at roughly 10 percent in this subgroup in Study 3—not ideal, but far better than the roughly 35 percent that we got in the full sample. Here, the 95 percent HIT approval rating appears to make a difference as well: our “upper bound” estimate of low-quality responses increased to nearly 18 percent in Study 2, which did not impose the 95 percent approval rate restriction. And, when it comes to trolling, just 3.4 percent of those Workers who completed more than 1,000 HITs admit to responding insincerely when asked. (Without the 95 percent completion rate restriction, this figure rises to 6.6 percent.)

Table 5. Low-quality responses by HIT completion rates

Note: Studies 1 and 3 imposed a 95% HIT completion rate restriction; Study 2 did not.

% Low-quality, index 1 includes suspicious IPs and incidences of trolling (per low-incidence screener measures); % Low-quality, index 2 includes suspicious IPs, incidences of trolling, and incidences of the date written in the DD/MM/YYYY format; % Low-quality, index 3 includes suspicious IPs, incidences of trolling, incidences of the date written in DD/MM/YYYY format, any non-date entered into the open-ended date question.

Consistent with Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Antoun, Yan and Conrad2020), then, we find that respondents who have taken lots of surveys tend to provide higher-quality data by observable measures. There is reason for caution, however. Respondents who reported having completed more than 1,000 HITs finished our surveys significantly more quickly than those who have completed fewer HITs. On average, these individuals took about 280 seconds to complete Study 3, making them 38 percent faster than those who reported completing 500–1,000 HITs. In Study 2, these high-HIT Workers were 15 percent faster than the 500–1,000 HIT respondents. While we cannot be certain, the fact that Workers with large numbers of completed HITs complete these surveys more quickly than other respondents suggests that these Workers may be gaining expertise in survey-taking if they complete enough HITs. These individuals may become better attuned to research hypotheses, which presents its own threats to validity (e.g., Campbell and Stanley, Reference Campbell and Stanley1963). Researchers should be mindful of these tradeoffs when designing studies on MTurk.

4 A market for lemons?

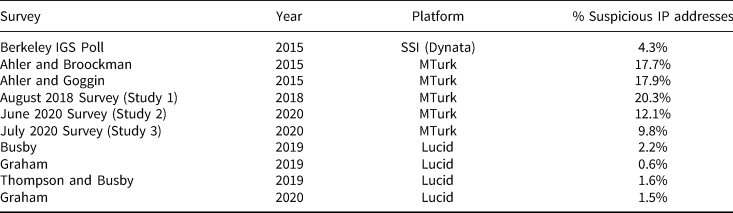

Thus far, we have provided some cursory evidence that low-quality responding on MTurk has increased over time. We have also theorized that low-quality responding may be more prevalent on MTurk than on other, more centrally managed survey platforms due to its unique incentive structure and information asymmetries. Now, we bring more evidence to bear on these questions by comparing rates of low-quality responses in MTurk studies to rates of low-quality responses on surveys conducted on Dynata (formerly Survey Sampling International) and Lucid, two relatively low-cost online panels.

To do so, we make use of data generously provided by other researchers. The first three datasets come from studies conducted in 2015. Two were administered using MTurk (Ahler and Broockman, Reference Ahler and Broockman2018; Ahler and Goggin, Reference Ahler and Goggin2019) and the other using SSI/Dynata (Institute of Governmental Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, 2015). The other four studies—Busby (Reference Busby2020), Graham (Reference Graham2021), Graham (Reference Graham2020), and Thompson and Busby (Reference Thompson and Busby2020)—were administered by Lucid either in 2019 or 2020.Footnote 17 While these studies did not include a trolling battery, we are able to provide an estimate of low-quality data based on suspicious IP addresses. As before, we made use of Know Your IP (Laohaprapanon and Sood, Reference Laohaprapanon and Sood2018) to determine the proportion of respondents in each study who circumvented location requirements, completed the survey more than once, took the survey from a location outside the US, or completed the survey using a blacklisted IP address.

Is the problem of responses from suspicious IP addresses unique to MTurk? The data presented in Table 6 suggest this is the case. Looking back, we can see that the prevalence of suspicious IP addresses on MTurk did not suddenly increase in 2018. Roughly 18 percent of the data in both Ahler and Broockman (Reference Ahler and Broockman2018) and Ahler and Goggin (Reference Ahler and Goggin2019) appear to originate from suspect IP addresses. This is not a far cry from the rate of bad IP addresses that we identified in Study 1 in 2018 (roughly 20 percent). And our estimates for the 2015 studies likely underestimate the proportion of IP addresses that are problematic. IP addresses turn over, especially those flagged for suspicious behavior. The data from 2015, therefore, may have a slight positive bias: some blacklisted IP addresses have likely been reassigned since then, which underestimates the scope of the problem at the time of data collection. By contrast, only about 4 percent of the data collected by SSI/Dynata for the Berkeley IGS Poll were flagged for suspicious IP addresses.

Table 6. Frequency of suspicious IP addresses across different platforms

As noted previously, the prevalence of suspicious IP addresses on MTurk has decreased significantly since 2019, when Amazon implemented restrictions to weed out bad actors (Amazon Mechanical Turk, 2019a, 2019b); the proportion of responses originating from suspicious IP addresses decreased by 50 percent among Workers with a 95 percent HIT approval rating between Study 1 and Study 3. That being said, MTurk still appears to disproportionately elicit respondents with suspicious IP addresses compared to Lucid, another relatively inexpensive survey platform. We estimate that there are still over five times as many bad actors in MTurk samples than in Lucid samples in 2020—and this is based only on suspicious IP addresses. While we suspect some Lucid survey-takers also engage in trolling or satisficing, the fact that Lucid institutes periodic quality checks on panel participants may incentivize respondents to behave more honestly.

Many researchers have turned to MTurk because it provides a low-cost alternative to curated, representative samples maintained by large survey firms. Unfortunately, it may no longer be significantly more cost-effective than higher-quality alternatives, especially after accounting for the 30 percent surcharge Amazon imposes on Requesters. Our June 2020 study paid respondents 75 cents per completed survey; the cost increased to about 98 cents per respondent after accounting for the surcharge. Our estimates suggest that 12 percent of Workers who completed that survey originated from suspicious IP addresses. In order to obtain a cost-per-minute for a valid survey, we divided the cost per non-suspicious response (97.5 cents) by the proportion of responses that were non-suspicious (0.879), and then divide that quantity by the survey length (15 minutes, both advertised and in reality, on average)—obtaining a cost of about 7 cents per minute. Following the same procedure for our July 2020 survey, we obtain a cost of ${0.35 \ast 1.3\over 0.902} \div 5 \rm { minutes} = 10$![]() cents per minute. By contrast, making use of information from Busby (Reference Busby2020), Thompson and Busby (Reference Thompson and Busby2020), Graham (Reference Graham2021), and Graham (Reference Graham2020), we estimate that researchers can obtain samples from an apparently higher quality panel at a similar cost: with a cost of $1 per respondent, just 2 percent of responses coming from suspicious IP addresses (see Table 6), and both surveys clocking roughly 10 minutes, we estimate a cost of approximately 10 cents per valid response per minute on Lucid.

cents per minute. By contrast, making use of information from Busby (Reference Busby2020), Thompson and Busby (Reference Thompson and Busby2020), Graham (Reference Graham2021), and Graham (Reference Graham2020), we estimate that researchers can obtain samples from an apparently higher quality panel at a similar cost: with a cost of $1 per respondent, just 2 percent of responses coming from suspicious IP addresses (see Table 6), and both surveys clocking roughly 10 minutes, we estimate a cost of approximately 10 cents per valid response per minute on Lucid.

This may, however, be a low estimate. As Thompson and Busby (Reference Thompson and Busby2020) describe, Lucid can be more expensive when sampling specific subgroups—that study paid $2 per respondent to sample only white Americans. At 10 minutes and with 1.6 percent of the sample coming from non-suspicious IP addresses, that study appeared to pay just over 20 cents per valid response. But the valid comparison on MTurk may involve greater costs as well, with more unknown unknowns: if a Requester attempts to restrict her HIT to a particular subgroup, she is liable to sample a significant number of people masquerading as members of that subgroup.

5 Consequences of low-quality responding

The results above suggest that there are at least three significant concerns with survey data collected on MTurk. First, even with location filters and improvements to the system since 2019, a non-trivial number of MTurk respondents take surveys from outside the United States. If—as we suspect—the majority of these respondents are foreign, many of our responses are provided from people from outside the sampling frame. Second, many respondents filed multiple submissions. Finally, a significant and rising proportion of MTurk Workers appear to provide intentionally humorous or misleading answers to survey items.

Some may assert that these problems are mere annoyances, as random responding could simply add “noise” to the data. But this noise itself may be a bigger problem than many assume. Not only can this imprecision bias estimates of frequencies and means of some measures—for instance, even answering questions randomly can positively bias estimates of how many people know something (Cor and Sood, Reference Cor and Sood2016)—but it can also attenuate correlations. In an experimental context in which researchers have control over the independent variable, T i—where i indexes survey respondents, each randomly assigned to a treatment or control group—and only the dependent variable, Y i, is vulnerable to noise, low-quality respondents will bias average treatment effects toward zero.Footnote 18

Consider an experimental data-generating process for which β1 ≠ 0: there is an average treatment effect (ATE) that is E[Y i|T i = 1] − E[Y i|T i = 0] ≠ 0. When we randomly assign subjects, under usual conditions, we obtain $\bar {Y_{i}} \vert T_{i} = 0$![]() and $\bar {Y_{i}} \vert T_{i} = 1$

and $\bar {Y_{i}} \vert T_{i} = 1$![]() , which we can use to compute an unbiased estimate of the ATE. But when there is haphazard responding by some subset of respondents j, $\bar {Y_{j}}$

, which we can use to compute an unbiased estimate of the ATE. But when there is haphazard responding by some subset of respondents j, $\bar {Y_{j}}$![]() is centered around neither E[Y i|T i = 1] nor E[Y i|T i = 0]. And since $\vert E[ \bar {Y_{i}} \vert T_{i} = 1] - E[ \bar {Y_{i}} \vert T_{i} = 1] \vert > 0$

is centered around neither E[Y i|T i = 1] nor E[Y i|T i = 0]. And since $\vert E[ \bar {Y_{i}} \vert T_{i} = 1] - E[ \bar {Y_{i}} \vert T_{i} = 1] \vert > 0$![]() and $\vert E[ \bar {Y_{j}} \vert T_{i} = 1] - E[ \bar {Y_{j}} \vert T_{i} = 1] \vert = 0$

and $\vert E[ \bar {Y_{j}} \vert T_{i} = 1] - E[ \bar {Y_{j}} \vert T_{i} = 1] \vert = 0$![]() , the average of the two will necessarily be smaller in absolute value than the former alone.

, the average of the two will necessarily be smaller in absolute value than the former alone.

Trolling presents potentially graver consequences. If people respond humorously or with the aim of being provocative, they will instead introduce more systematic error into estimates (e.g., Lopez and Hillygus, Reference Lopez and Hillygus2018). That is, in these cases, we might expect that a subset of respondents with a predilection for trolling, indexed by k, would provide average responses E[Y k|T k = 1] ! = E[Y i|T i = 1] and E[Y k|T k = 0] ! = E[Y i|T i = 0]. Thus, trolling's effects are likely idiosyncratic to samples, treatments, and dependent measures. But either pitfall—attenuation of treatment effects from inattentive responding or biased effect estimates from trolling—threatens our ability to draw accurate inferences from an experimental design.

To study how low-quality responses influence the substantive conclusions reached in a study, we made use of data collected as part of an experiment on partisan motivated reasoning fielded by Roush and Sood (Reference Roush and Sood2020) in Study 2.Footnote 19 The experiment tested the hypothesis that partisans interpret the same economic data differently depending on the party to which economic success or failure is attributed. Specifically, Roush and Sood (Reference Roush and Sood2020) provided respondents with real economic data from 2016—collected by the Federal Reserve—demonstrating a decrease in the unemployment rate from 5.0 to 4.8 percent and a decrease in the inflation rate from 2.1 to 1.9 percent. Importantly, respondents were randomly assigned to receive one of two partisan cues preceding the question preamble: one-half of respondents were told that “During 2016, when Republicans controlled both Houses of Congress, [unemployment/inflation] decreased from X percent to X percent...” and the other half were told that “During 2016, when Barack Obama was President, [unemployment/inflation] decreased from Y percent to Y percent...” Respondents were then asked to interpret these changes and evaluate whether unemployment or inflation “got better,” “stayed about the same,” or “got worse.” Since prior research demonstrates that partisans interpret economic conditions favorably when their own party is in power and unfavorably when the other party is in power (e.g., Bartels, Reference Bartels2002; Bisgaard, Reference Bisgaard2015), we expected that Democrats will be more likely than Republicans to interpret these slight decreases as improvements when they receive the President Obama cue, while Republicans will be more likely to interpret these same statistics positively when they receive the Republicans-in-Congress cue. In other words, we expected that partisans are more likely to classify a 0.2-point reduction in unemployment or inflation as “getting better” under a co-party president while interpreting this same reduction as unemployment and inflation “staying the same” or “getting worse” under out-party leadership.

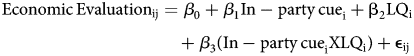

We recoded the data so that treatments and respondents are characterized in relation to one other: Democrats who saw the President Obama cue and Republicans who saw the Republicans-in-Congress cue were classified as receiving an In-party cue, whereas Democrats who saw the Republicans-in-Congress cue and Republicans who saw the President Obama cue are classified as receiving an Out-party cue. To determine how low-quality responses moderate this expected treatment effect, we adopted the following model:

where i indexes individual survey respondents, j indexes survey items (e.g., whether the respondent is assessing unemployment or inflation), and LQ i is an indicator for low-quality response. We operationalized low quality four ways in four different models. The first includes respondents flagged for any reason; the second includes only those respondents who completed the survey from a suspicious IP address; the third includes only those respondents flagged for potential trolling; and the fourth includes only those respondents who self-reported completing 1000 HITs or more. All variables were recoded 0–1 for ease of interpretation.

5.1 Results

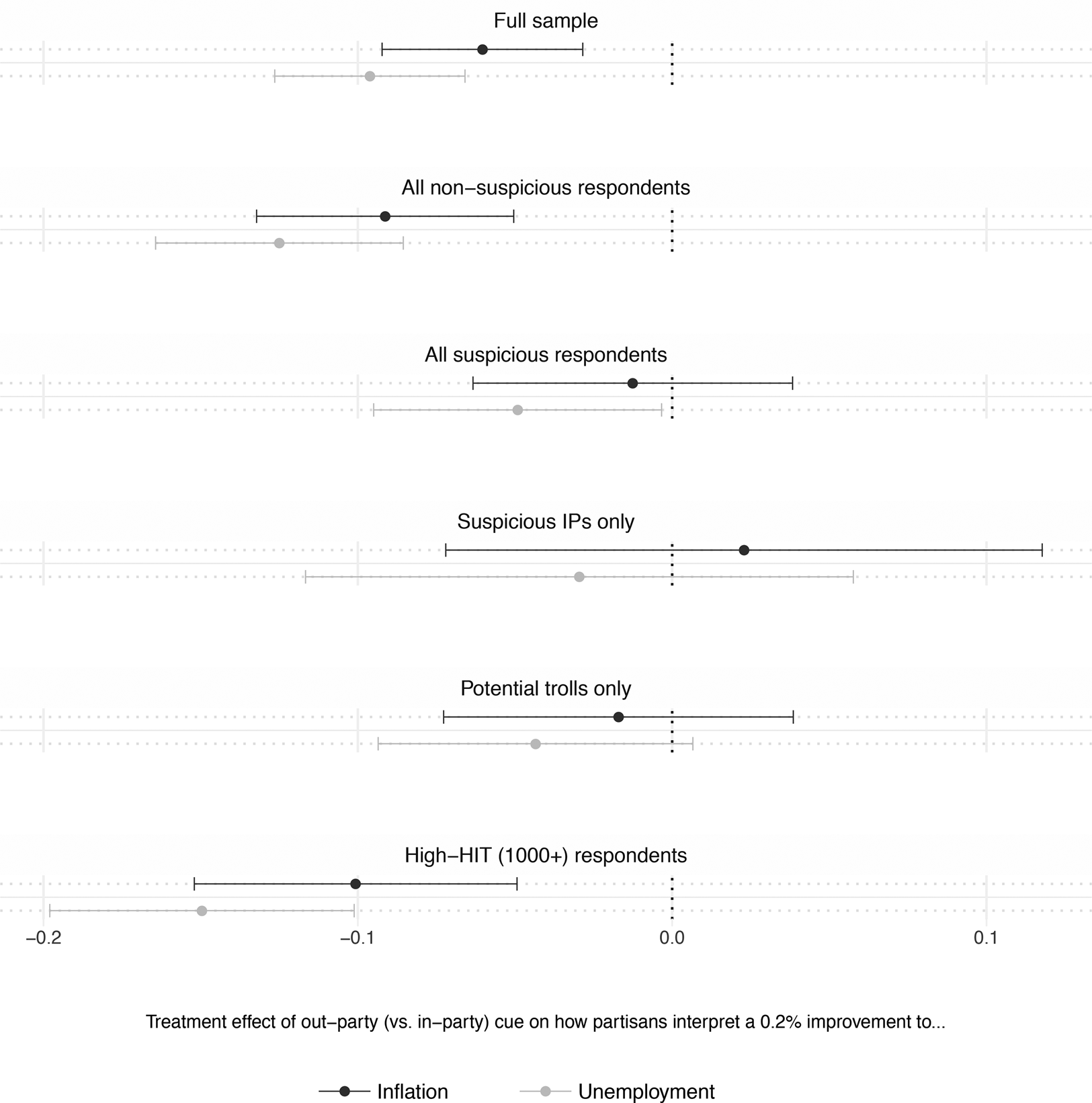

As Figure 2 shows, MTurk respondents who misrepresent themselves or answer questions insincerely can significantly affect experimental inference.Footnote 20 The first panel presents the results among the full sample, and the subsequent panels show the results for the other aforementioned subgroups. The second panel presents the experimental results among respondents not flagged for any reason. As expected, non-suspicious respondents who identified as Democratic or Republican—or as Independents who “lean” toward one of the parties—provided systematically different assessments of US economic performance depending on the partisan cue they received. These respondents evaluated the slight decrease in unemployment 12.5 percentage points more positively, on average, when the change was attributed to their own party (95 percent CI: [8.5, 16.4]). Similarly, they evaluated the marginal decline in inflation 9.1 percentage points more positively when presented with a cue implicitly crediting their own party (95 percent CI: [4.9, 13.2]).

Figure 2. Experimental effects by subgroup.

The analogous treatment effects are decidedly smaller among the 579 respondents marked as suspicious. Panel 3 in Figure 2 presents these effects. Suspicious respondents responded to the treatment, albeit less strongly than non-suspicious respondents: partisans evaluated the 0.2 percentage point decrease in unemployment 5.3 points more positively when responsibility was attributed to their own party (95 percent CI: [0.8, 9.8])—a treatment effect consistent with the study's hypotheses, but also one significantly smaller than that among all non-suspicious respondents. We found no effect of the partisan cue on these respondents’ evaluations of the change in inflation, however; the coefficient is neither statistically significant nor substantively meaningful.

The overall effect of suspicious respondents in the sample is an attenuation effect of 28 percent. The average treatment effect (ATE) of the out-party cue on assessments of the unemployment rate, among all respondents, is − 0.10 (95 percent CI: [− 0.13, − 0.07]). The ATE of the out-party cue on assessments of inflation, again among the full sample, is − 0.06 (95 percent CI: [− 0.09, − 0.02]). Among all suspicious respondents, the analogous ATEs are − 0.05 and − 0.02, as shown in panel 3 in Figure 2. We divide the estimated ATE among non-suspicious respondents by the estimated ATE in full sample to obtain the relative size of the observed effect to the “real” effect—the attenuation ratio. We calculate the average attenuation ratio across outcome variables, weighted by the inverse of the standard error of these estimated ATEs, as 0.72; that is, our observed effect is 72 percent of what it would be without the suspicious respondents. Subtracting the attenuation ratio from 1 yields the attenuation effect in percentage terms: in this case, 28 percent.Footnote 21 At the very least, researchers planning to conduct experiments on MTurk should consider this when conducting a priori power analyses.

It is worth noting the similar pattern of treatment effects (or lack thereof) among respondents using suspicious IP addresses (panel 4 in Figure 2) and respondents who are flagged as potential trolls (panel 5 in the same figure). This may be due to a similar data-generating process: respondents flagged as likely to be potential trolls may have been classified as such because of inattention, which would add noise to the data in a similar manner as random responses from someone who does not speak English or pay attention to U.S. politics. Theoretically, these bad actors pose an even larger problem if they attempt to respond to treatments in humorous or intentionally idiosyncratic ways. This does not appear to be the case here, but we provide one potential example of such behavior in SI 4.

Finally, the last panel speaks to the potential efficacy of restricting HITs to experienced MTurk Workers, consistent with Amazon's suggested best practices (Amazon Mechanical Turk, 2019b). This subsample reacted the most strongly to the treatment, with a 15-point average difference in evaluations of unemployment between experimental conditions (95 percent CI: [10.1, 19.8]) and a 10-point difference in evaluations of inflation (95 percent CI: [4.9, 15.2]). We are unable to fully parse different explanations for this group's responsiveness, though. On the one hand, people who have been in the MTurk pool long enough to complete more than 1000 HITs—most of which are not surveys—may be especially detail-oriented, and they may react more strongly to treatments because they read more closely. On the other hand, if they take lots of surveys, they may have developed a sense for research hypotheses and may try to respond in a hypothesis-consistent fashion. When considering qualifications based on HITs completed, experimenters using MTurk may thus face a tradeoff between respondents’ attentiveness and the pitfalls of “professional survey responding.” But the rate of bad actors among Workers with relatively low HIT counts—upward of 30 percent, according to Table 5—tips the scales in favor of using such a qualification.

6 Discussion and conclusion

Our studies demonstrate significant data quality problems on MTurk. In 2018, 25 percent of the data we collected were potentially untrustworthy, and that number held roughly constant into July 2020 (27 percent). The apparent contours of the problem shifted over that time period, though: the presence of duplicated and foreign IP addresses fell by about 50 percent, but the rate of apparently insincere responding—or “trolling”—rose by 200 percent. This is worth noting because the effects of these particular low-quality responses are less clear. While random responding due to satisficing, poor understanding of English, or ignorance of American politics—the latter two coming from respondents from other countries masquerading as U.S. adults—is liable to add significant noise to data collected, insincere and/or humorous responding may follow systematic patterns and thus add bias. Our studies also suggest that “problematic” respondents on the platform respond differently to experimental treatments than other subjects. Specifically, we find that bad behavior (responses originating from suspicious IP addresses or those which indicate potential trolling) adds noise to the data, which attenuates treatment effects—in the case of our experiment, by 28 percent.

Current data quality may be poor, but what's the prognosis? Since concerns about a “bot panic” surfaced in the summer of 2018, Amazon implemented several reforms designed to cut down on the number of Workers gaming the platform for personal gain. These measures include requiring U.S. Workers to provide official forms of identification, shutting down sites where Worker accounts are traded, and monitoring Workers using IP network analysis and device fingerprinting (Amazon Mechanical Turk, 2019a, 2019b). While these measures may catch some of the worst offenders, we believe that platform's strategic incentives will cause Worker quality to continue to decline as participants devise new ways to game the system. The end result is that MTurk may indeed be emerging as a “market for lemons” in which bad actors eventually crowd out the good.

As it stands, researchers committed to paying a fair wage on MTurk may do just as well contracting with an established survey sampling firm. While we found some evidence of suspicious responding in samples curated by SSI (now Dynata) and Lucid, these rates are a fraction of their apparent analogs on MTurk. More importantly, according to our cost-benefit analysis, MTurk may not even be that much more cost-effective, if at all. Studies 2 and 3 cost 7.4 and 10.1 cents per valid respondent per minute, and we conservatively estimate that researchers can conduct research on Lucid (e.g., Coppock and McClellan, Reference Coppock and McClellan2019) for just over 10 cents per minute (e.g., Busby, Reference Busby2020; Graham, Reference Graham2021, Reference Graham2020). With the benefits of working with an established panel—the external validity from a more representative sample, being able to conduct within-subjects experiments in a single wave thanks to panel variables—we suspect that MTurk may be best used for testing item wording, piloting treatments, and other quick research tasks.

This is partly because the chances of improvement seem low unless we can craft and implement better methods to assess and incentivize quality responding on MTurk. Ultimately, it is important that the methods we devise preclude new ways of gaming the system, or we are back to square one. For now, we can think of only a few recommendations for researchers:

• Use geolocation filters on platforms like Qualtrics to enforce any geographic restrictions.

• Make use of tools on survey platforms to retrieve IP addresses. For example, run each IP through Know Your IP to identify blacklisted IPs and multiple submissions from the same IP, or make use of similar packages built for off-the-shelf use in Stata and R (see Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Clifford, Burleigh, Waggoner, Jewell and Winter2020).

• Include questions to detecting trolling and satisficing; develop new items to this end over time, so that it is harder for bad actors to work around them.

• Caveat emptor: increase the time between HIT completion and auto-approval so that you can assess your data for untrustworthy responses before approving or rejecting the HIT. We approved all HITs here because we used all responses in this analysis. But for the bulk of MTurk studies (i.e., those not being done to audit the platform), researchers may decide to only pay for responses that pass some low bar of quality control. But caveat lector: any quality control must pass two tough tests: (1) it should be fair to Workers, and (2) it should not be easily gamed.

Rather than withhold payments, a better policy may be to implement quality filters and let Workers know in advance that they will receive a bonus payment if their work is completed honestly and thoughtfully. This would lead to a weak signal propagating the market in which people who do higher quality work are paid more and eventually come to dominate the market. If multiple researchers agree to provide such incentives around reliable quality checks immune to being gamed, we may be able to change the market. Another possibility is to create an alternate set of ratings for Workers not based on HIT approval rate—much like how Workers can use Turkopticon to assess Requesters’ generosity, fairness, etc.

• Be mindful of compensation rates. While stingy wages will lead to slow data collection times and potentially less effort by Workers, unusually high wages may give rise to adverse selection—especially because HITs are shared on Turkopticon, etc., soon after posting. A survey with an unusually high wage gives large incentives to foreign Workers to try to game the system despite being outside the sample frame. Social scientists who conduct research on MTurk should stay apprised of the current “fair wage” on MTurk and adhere accordingly. Along the same lines, though, researchers should also stay apprised of the going rate for responses on other platforms.

• Use Worker qualifications on MTurk and include only Workers who have a high percentage of approved HITs into your sample. While we have posited that HIT completion rates are likely a biased signal for quality, filtering Workers on an upper-90s completion rate may weed out the worst offenders. Over time, this may also change the market.

• Restrict survey participation to Workers who have a proven track record on MTurk—those who have completed a certain threshold of HITs. Suspicious and insincere responding fell off noticeably among respondents with 1000 or more completed HITs in Studies 2 and 3, and others have noted 5,000 as an effective threshold (Amazon Mechanical Turk, 2019b). But note the tradeoff here—unless the Workers in question primarily complete non-survey tasks, researchers face a sample made entirely of highly experienced survey-takers, which raises questions about professional responding, demand effects, and the degree to which findings generalize to people who do not see public opinion instruments on a regular basis. (This, e.g., might be especially troubling in studies involving political knowledge.)

• Importantly, research contexts that preclude the collection of IP addresses present unique challenges for scholars using MTurk. For example, researchers in the European Union are barred from collecting such information by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Not only do these researchers face significant unknown unknowns regarding their MTurk samples, but such rules may even incentivize bad actors to seek out MTurk surveys fielded in these contexts. Ultimately, the strength of professionally managed online survey panels is their selective recruiting of panelists based on known demographic characteristics. In contexts that preclude researchers from collecting IP addresses, these firms may do especially well (in terms of the relative quality of their product and in a prospective economic sense). But note that researchers who cannot collect IP addresses are not completely fumbling in the dark. It is possible to devise items that can parse respondents in one's desired sampling frame from those masquerading as someone else (e.g., asking purported Americans to write the date in MM/DD/YYYY format, showing purported Brits a picture of an elevator [or “lift”] or trash can [“bin”] and asking them to name it). Similarly, the low-incidence screener battery may be adopted across contexts to identify potentially insincere responses.

• Note that we have only touched on a handful of particular data quality issues—respondents posing as someone they are not or offering insincere responses. Other issues, including attentiveness (Thomas and Clifford, Reference Thomas and Clifford2017), exist—and researchers should constantly be mindful of emerging threats to survey data quality.

Ultimately, researchers ought to recognize that MTurk is liable to be more prone to “lemon” responses for two reasons. First and foremost, unlike other online survey panels, MTurk does not recruit respondents based on known characteristics, thereby increasing the likelihood of obtaining respondents masquerading as someone else. Not only do MTurk Requesters know nothing about these respondents in advance, but they make up thousands of independent employers rather than one central management system. This means that the only signal of response quality propagated to the market is HIT approval. On any paid platform, non-serious responding is bound to be a concern, but our analysis suggests the problem is magnified on MTurk.

Recognizing these specific issues may just be the tip of the iceberg. The Belmont Report forever changed social science by clarifying researchers’ relationship with study participants, emphasizing that we must treat those who generate our data with respect, beneficence, and fairness. It was a necessary response in a time of reckoning with traumatic treatments and exploitative recruitment practices. But we believe that we are currently reckoning with a new problem in our relationship with research participants—one that demands we add “respect for validity of data” to the framework that guides this relationship. We do not believe this call is inconsistent with respect for persons, beneficence, or justice. In particular, a solution starts with researchers thoughtfully gathering data: using more credible alternatives to MTurk when possible, especially making use of pre-existing variables in online panels to leverage within-subjects studies’ statistical power; using respondent requirements thoughtfully on MTurk; and, ultimately, being clear about the expectations of respondents when obtaining their consent. With these broad principles, we believe that researchers can recruit good-faith participants while fairly avoiding—and screening out, when necessary—those who contribute to the data quality problem.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.57.

Acknowledgements

This title is inspired by George Akerlof's (Reference Akerlof1970) seminal paper on quality uncertainty in a market, “The Market for Lemons.” We are grateful to Ethan Busby, Don Green, Stephen Goggin, Matt Graham, Jonathan Nagler, John Sides, Andrew Thompson, and the anonymous reviewers for the useful comments and suggestions. Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 12th Annual NYU-CESS Experimental Political Science Conference, February 8, 2019 and at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, April 6, 2019.