To address escalating rates of chronic conditions such as obesity, there has been a gradual paradigm shift from focusing on individual dietary behaviours to addressing the food environments from which people make their food choices( Reference Holsten 1 – Reference Story, Kaphingst and Robinson-O’Brien 3 ). Food policy coalitions (also referred to as ‘food policy councils’, ‘food alliances’ or ‘local food networks’) are cross-sectoral groups which ‘work at the intersection of health, social justice and environmental sustainability to improve local and regional food systems and influence government policy’( Reference Caraher, Carey and McConell 4 ) (p. 79). This collaborative and coordinated approach enables food policy coalitions to work on systems-level issues including food production, consumption, processing, distribution and waste recycling( Reference Harper, Shattuck and Holt-Giménez 5 , Reference Siddiki, Carboni and Koski 6 ). Evidence suggests that food policy councils and coalitions have been set up as a response to the lack of governmental bodies that can set or create food policy independently( Reference Broad Leib 7 ).

The evidence behind food policy councils and coalitions stems largely from North America. Their origins can be traced back to state nutrition councils which operated in the 1960s( Reference Clancy, Hammer and Lippoldt 8 ). Since the early 1980s, there has been steady increase in the number of food councils operating at the local, regional and state levels in North America( Reference Winne 9 ) and a 2015 audit found 278 food policy councils across the USA and Canada( 10 ). An evidence review of thirteen food policy councils in North America found that many focused more attention on programmatic as opposed to policy work( Reference Schiff 11 ). An analysis of eighteen food policy councils in the USA found variation in terms of their policy outputs, the most prevalent foci being food access, security and justice (fifteen councils), followed by health and nutrition (ten councils)( Reference Siddiki, Carboni and Koski 6 ). Yet few in-depth case studies have been conducted that evaluate the opinions and priorities of various stakeholders within a single food policy council or how councils operate in practice( Reference Sadler, Arku and Gilliland 12 ). There is a need for more evidence relating to the processes and impacts of food policy councils/coalitions( Reference Scherb, Palmer and Frattaroli 13 ) and how they can influence local food environments.

Compared with North America, the concept of food policy councils is relatively new in Australia( 14 ) and published data regarding the number in operation and evaluations of their strategies are scarce. One example of a state-level cross-sectoral food coalition is the Sydney Food Fairness Alliance, which was formed in 2005 to advocate for a socially, economically and environmentally sustainable food system in the state of New South Wales( 15 ). The Alliance has coordinated a series of submissions in response to government inquiries relating to income inequality and land use, and has advocated for the development of a state government food policy. In the state of Victoria, the Food Alliance was established in 2010 with funding from VicHealth (a health promotion foundation funded from state monies) in partnership with a university. It was established following a scoping report which identified the need for a food policy coalition to coordinate the disjointed and ‘piecemeal’ food security efforts of the government and non-government sectors( Reference Loff, Crammond and McConnell 16 ). The priorities of this alliance were to create a resilient fruit and vegetable supply, embed local food within public-sector food procurement policies and develop a whole-of-government food policy( Reference Caraher, Carey and McConell 4 ). A few years later, the Victorian State Government Department of Health and Human Services created the Healthy Food Connect Framework to support the coordination of food security efforts in local government areas( 14 ). This framework recommended the creation of food system-related partnerships, projects and policies, as well as the establishment of local food coalitions. It was anticipated that this framework would support the creation of twelve local-area food coalitions by 2015( Reference Caraher, Carey and McConell 4 ); however, no evidence exists about the number of coalitions established or their impact on local food environments.

The focus of the present study is a local-area food policy coalition that was established prior to and independent of the development of the Healthy Food Connect Framework. The study aims to explore how an Australian food policy coalition acts to influence a local food environment, focusing specifically on its composition, functions and processes as well as its food-related strategies and policy outputs. The three broad research questions are:

-

1. What membership structures allow a food policy coalition to operate effectively?

-

2. How does a food policy coalition function to address food systems issues?

-

3. What food environment strategies and policies can a food policy coalition influence?

Methods

Design

A qualitative case study approach was chosen for the evaluation. A case study approach is an in-depth exploratory methodology for investigating relationships between a phenomenon and the context in the environment where it occurs, taken from the perspective of those involved( Reference Yin 17 , Reference Stake 18 ). A key advantage of case study methodology is that it can facilitate the collection of data from multiple sources, which provides a rich and detailed understanding of reality( Reference Amaratunga and Baldry 19 ). Ethical approval for the current study was obtained from the relevant university human research ethics committee.

Community Coalition Action Theory was chosen as an organising framework for this evaluation, specifically to guide the development of research questions and participant interview questions. This theory was coined by Butterfloss and Kegler to provide an underlying theoretical framework on which most community coalitions can be built( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ). Its theoretical basis borrows from arenas such as community development, citizen participation, political science, inter-organisational relations and group process. The theory proposes that community coalitions move through a cyclical process of formation (recruiting and mobilising coalition members), maintenance (establishing organisational structures and processes, planning for action and selecting strategies) and institutionalisation (implementing strategies, refining/evaluating outcomes and creating community change). This framework has been referred to in existing food policy council research( Reference Schiff 21 , Reference Dean 22 ). It comprises constructs which relate to community coalition formation, structure, processes, interventions and outcomes( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ).

Context and setting

The case study relates to a sub-regionally focused food policy coalition that was established in August 2010. It spans two local government areas on the south-eastern coast of Victoria, Australia. In this rural region, the agri-food sector and tourism are major industries, with agriculture comprising approximately 80 % of land use( Reference Profile 23 , Reference Profile 24 ). The coalition was started by a state government-funded non-profit agency which acts as a voluntary alliance of local service providers, including acute and community health services, disability services, local government, the division of general practice, welfare services and community-based services. The food policy coalition was established to provide a focal point for discussion and action on local food security initiatives, which is similar to the Sydney Food Fairness Alliance and Food Alliance described previously. Its objectives relate to the sharing of technical and strategic knowledge, assessing how the local food system operates, encouraging more organised advocacy efforts, proposing strategies, and influencing political decision making and policy. These objectives align closely with the common characteristics and objectives of many North American food policy councils, which include forming partnerships among different food sectors, researching and analysing local food systems, developing programmes and advocating for food system policy change( Reference Caraher, Carey and McConell 4 ).

The coalition is coordinated by a state government-funded agency, which provides a physical space for coalition operation. Meetings are chaired by one paid staff member of this agency. Any additional funding for the coalition is sought through external grant monies. Members can either self-select to be part of the coalition or are recommended by the coalition chair or members. Coalition meetings are scheduled at the start of each year and generally take place on a quarterly basis. Since its inception, the coalition has undergone a series of member surveys. However, the coalition members identified a need for a more comprehensive evaluation of the coalition’s operation, function and impact, and the chair approached the study authors to conduct the evaluation. The authors’ decision to conduct the evaluation was based on the coalition’s four-year history of working to improve local food environments and the need for more evidence to justify recent state-wide interest in establishing food policy coalitions( 14 ).

Data collection

The evaluation comprised three forms of data collection: (i) in-depth interviews with coalition members; (ii) document analysis; and (iii) observation of a coalition meeting. Data source triangulation was employed to confirm emerging themes of interest and add rigour to the qualitative approach( Reference Liamputtong 25 ). The data collection and analysis were undertaken by researchers who are independent of the coalition but have experience in mobilising local agencies to improve access to nutritious food.

Coalition member interviews

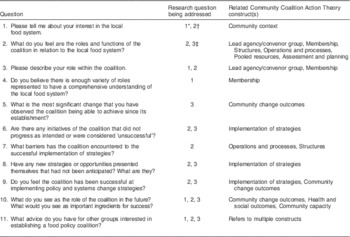

Semi-structured in-depth qualitative interviews were chosen as a method to evaluate members’ experience of participating in the coalition. An interview guide was developed consisting of open-ended questions and prompts. Interview questions were aligned with the constructs of Community Coalition Action Theory, which relate to the stages of development of a community coalition( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ). Table 1 outlines the interview questions and how they align with each research question of the study and the constructs of Community Coalition Action Theory. These constructs include the coalition’s: community context (factors in a community environment which can impact a coalition); lead agency/convenor group; membership; operations and processes (including communication, decision making and conflict management); structures (including formalised rules, roles and procedures); synergy (including pooled resources, member engagement and assessment/planning); implementation of strategies; and community change outcomes (including changes in community capacity to solve problems).

Table 1 Participant interview guide and enquiry logic

* What membership structures allow a food policy coalition to operate effectively?

† How does a food policy coalition function to address food systems issues?

‡ What food environment strategies and policies can a food policy coalition influence?

The coalition chair identified and invited all current, actively engaged coalition members to participate in an interview, which at the time of the study was eleven participants. Corresponding members (who choose to connect to the coalition for personal or professional interests via an email list but not attend meetings) were not invited to participate in an interview. The purposive sample of current members with the greatest involvement in the coalition was selected based on their attendance at coalition meetings and knowledge of coalition activities. This form of sampling involved the deliberate selection of specific individuals due to the rich information they could provide, specific to the coalition( Reference Liamputtong 25 ). Of the eleven current members selected, all (100 %) provided written consent to participate in an in-depth interview.

Eleven face-to-face interviews were conducted in November and December 2014 by the first author at various locations that were convenient for participants throughout the coalition catchment area. Interview length varied between 25 and 55 min. Interviews were of an informal nature, which provided coalition members the flexibility to raise issues of most interest and importance to them. Participants were given the opportunity to focus on their own experiences and perspectives of being a member of the coalition, thereby enabling researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the issues( Reference Patton 26 ). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Field notes were taken during the interviews to aid interpretation and meaning behind participant responses.

Documents relating to the coalition

An electronic folder with all documents relevant to the coalition was provided to the researchers by the coalition chair. These included meeting minutes (fourteen regular coalition meetings, three task-focused meetings), Terms of Reference (which describe the purpose, structure and scope of the coalition; two versions), project briefs and reports (n 3; 52 pages), grant and award applications (n 3), letters of support (n 2), workshop flyers and invitations (n 2), submissions to government plans and inquiries (n 1) and press releases/media articles (n 2). In addition, two local government public health and well-being plans, one local-area integrated health promotion plan, one local government aspirational/visionary policy and one local government land-use policy were sourced from the Internet. The first author also contacted three coalition members to verify the interpretations of information contained in the two local government public health and well-being plans and the local government land-use policy.

Observation of a coalition meeting

The first author attended and observed one coalition meeting in February 2015, after the coalition member interviews had taken place. Permission to attend the meeting was granted after the coalition chair had sought permission from members. The first author took notes (5 pages) during the 2 h meeting, recording a summary of discussion points, decisions and the author’s interpretation of dynamics between group members. These notes were incorporated into the data analysis.

Data analysis

Coalition meeting minutes were analysed by the first author and checked by the second author to generate basic descriptive statistics regarding coalition attendance by sector and location. This provided additional data to answer the research question regarding coalition composition/membership.

Interview and document data were analysed using a thematic and constant comparison approach( Reference Patton 26 ). Data source triangulation took place as multiple sources of qualitative text (interview transcripts, coalition documents and field notes) were compared and contrasted to give researchers a deeper understanding of the coalition and to assist in developing meaning( Reference Liamputtong 25 ). For the purposes of maintaining participant confidentiality, each interview transcript was assigned a unique identifier, a randomly selected number from 1 to 11. Transcripts were cross-checked against researcher field notes to ensure validity and to aid interpretation.

Qualitative text from all sources was organised and open-coded by the first author using NVIVO software version 10 (QSR International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia). Both authors conferred over the coding scheme and codes were grouped into similar categories. Categories were then considered in light of the research questions to develop themes. Verbatim quotations from interviews were selected to illustrate the themes and describe the personal experiences of coalition members.

Member checks are recognised as a procedure that can increase the reliability and validity of qualitative research, by determining whether data and findings reflect participants’ realities( Reference Hoffart 27 ). Preliminary themes and findings were presented by the first author to members at a coalition meeting in July 2015 to test the investigators’ interpretation of the data and seek corroboration or criticism from members. There was general agreement that the chosen themes reflected the experiences of coalition members.

Results and discussion

Since its establishment in August 2010 until February 2015, the coalition met seventeen times, attracting an average of eight participants per meeting (sd 3). At the commencement of the present study (October 2014), the coalition had eleven actively participating members and ten corresponding members. Of the eleven active coalition members, two were male and nine were female. Additional information relating to the members who participated in the present study is summarised in Table 2. Data analysis revealed five key themes, which are described below.

Table 2 Coalition member information (current active members)

* Role changed while participating in the coalition.

Theme 1: coalition work is driven through leadership structures and processes

Community Coalition Action Theory emphasises the importance of coalition leaders organising a structure for coalition members to remain committed to their efforts( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ). The case study food policy coalition is led by a paid staff member within a state government-funded agency, which acts as an alliance of local health and human service providers. This non-profit agency operates external to local government. Members unanimously stated that a dedicated facilitator is needed to oversee the administrative tasks of the coalition. There was general agreement that the coalition’s lead agency was suitable given its core functions of capacity building and partnership development.

Many members commented favourably about the relative neutrality of the coalition, stating that if it were a local government-driven activity, politics would get in the way:

‘It does need to continue to be managed by the [current lead agency] in the sense that … it is neutral territory.’ (Coalition member 4)

Neutrality was reported as an important consideration to mitigate potential bias that may arise. Lang et al. have stated that ‘[Policy councils] could establish sorely needed neutral ground between departments of government’( Reference Lang, Rayner and Rayner 28 ) (p. 16). Community coalition literature suggests that a coalition leader’s role is to encourage collaboration between member organisations, which can involve conflict, negotiation and compromise( Reference Butterfoss, Goodman and Wandersman 29 ). Furthermore, it is generally agreed that a coalition leader should foster shared decision making with the membership and deal with differences in a respectful way, which requires flexibility to negotiate different priorities and effective mechanisms for democratic planning( Reference Butterfoss, Goodman and Wandersman 29 – Reference Webb, Pelletier and Maretzki 31 ). Document analysis revealed strong governance procedures for this coalition, including annual opportunities for members to revise the Terms of Reference, frequent member surveys and timely coordination of meeting procedures and paperwork.

Another key leadership consideration for a food policy coalition is to conduct internal reviews of the coalition’s direction( Reference Webb, Pelletier and Maretzki 31 ) and to structure coalition activities as community-engaged processes( Reference Fitzgerald and Morgan 32 ). Members expressed that previously the focus of the coalition was too broad and there was a need to prioritise strategies to focus on. External funding was obtained and the coalition’s lead agency employed a project worker to engage the local community, conduct a situational analysis of the local food environment and formulate a series of recommendations for the coalition to pursue. An action plan was adopted, assigning actions/tasks/strategies for coalition members to complete, which will drive future work of the coalition. Many interviewees commented positively about this step:

‘[The coalition] just seems more organised and to function more as a body with a little bit of oomph behind it instead of just a committee getting together to have a chit-chat.’ (Coalition member 9)

Based on the first author’s observations at a coalition meeting following discussion about the food system situational analysis, members appeared to appreciate the opportunities that the coalition chair had created to guide the direction of the coalition.

Theme 2: a coalition’s membership is strengthened through diverse perspectives and skills

Evidence suggests that a coalition’s membership is its primary asset as each member can bring a different set of knowledge and skills( Reference Butterfoss, Goodman and Wandersman 29 ). Food policy councils generally exist to create a mechanism for disparate sectors to collaborate on food system issues( Reference Scherb, Palmer and Frattaroli 13 ). Membership can consist of farmers, retailers, anti-hunger and food justice advocates, education sector representatives, health and government representatives and concerned citizens( Reference Harper, Shattuck and Holt-Giménez 5 , Reference Borron 33 ). The ‘Membership’ construct of Community Coalition Action Theory states that coalitions usually consist of a core group of people who are committed to resolving a health or social issue (in this case, issues relating to the local food environment)( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ). Table 3 lists the various sectors that have been represented at meetings of the food policy coalition under study between August 2010 and February 2015. Several members commented favourably about the current composition, stating that members brought a broad range of skills and connections to the coalition. These included skills in grant writing, community engagement and advocacy, which have all been identified in the literature as being a core function of food policy councils( Reference Harper, Shattuck and Holt-Giménez 5 ).

Some members questioned the over-representation of local government representatives and the number of ‘bureaucrats’ attending meetings. However, all commented positively about the presence of local government in the coalition, stating that this sector had the greatest capacity to make bigger picture change and influence the system at a higher level:

‘You have to be able to work within the framework of government to be able to have an influence.’ (Coalition member 1)

Evidence suggests that buy-in from government is a factor towards increasing the legitimacy of a food policy council and visibility of its efforts( Reference Clayton, Frattaroli and Palmer 34 ). An evaluation of eighteen food policy councils across the USA found that all but two had formal state or local government representation( Reference Siddiki, Carboni and Koski 6 ).

The analysis suggested that the reach of the coalition was well beyond its current membership, largely due to how well members were connected to other networks, sectors and stakeholders. Examples included one coalition member chairing a network of local farmers and food producers and another whose local government economic development role was to forge relationships with local businesses and the agriculture industry. Several members cautioned against broadening the representation beyond the core group, highlighting that it would be challenging to remain focused. General consensus was to retain the small size of the coalition (keeping the average attendance of eight participants per meeting), seek different perspectives by utilising members’ existing networks and hold community forums when needed:

‘It may be better to look at a smaller group of eight/nine, and then from that group broaden it out … through workshops and other such things.’ (Coalition member 7)

This is supported by Community Coalition Action Theory which states that coalitions are more effective when the core group includes ‘community gatekeepers’ who thoroughly understand the community( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ). Smaller-sized coalitions have also been perceived as being more efficient and effective with decision-making processes, compared with larger more diverse coalitions( Reference Webb, Pelletier and Maretzki 31 ).

Overall, members commented that the current membership mix was effective, valuing the opportunity to bring together diverse opinions and learn from the skills and experiences of one another:

‘It’s been fantastic for me to have other people speaking different languages than I do … I think that’s been crucial. Some of the other health promotion networks that exist here haven’t got the same energy or passion behind them, and I think that’s because [this coalition has] got different points of view and different perspectives.’ (Coalition member 3)

Such different perspectives were recognised as a factor which built energy and motivation for members to continue to meet and collaborate.

Theme 3: food system advocacy can be achieved through the pooling of resources

The pooling of perspectives and resources has been recognised as one of the hallmarks of community coalitions( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ). The ‘Pooled Resources’ construct of Community Coalition Action Theory recognises that ‘the synergistic pooling of member and community resources prompts effective assessment, planning and implementation of strategies’( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ) (p. 165). Terms such as ‘focal point’, ‘hub of the wheel’, ‘political umbrella around food’ and ‘catalyst for bringing people together across networks’ were used by members to describe the coalition under study. It was commonly stated that the coalition’s function was to pool resources, especially in light of the limited availability and short-term nature of funding. Several members recognised that a barrier to improving the local food environment was difficulty in obtaining project funding, and that available funding was often insecure, short-term and subject to the vagaries of changing governments and policy agendas. However, many members reflected that the coalition still functioned well without extra funding and that they pulled together to make the best with what they have:

‘One of the big achievements is that everything’s been done without much funding. It’s just been done with goodwill along the way pretty much. [It has] just been people working together.’ (Coalition member 11)

Such pooling of assets can be significant when a coalition has few resources of its own( Reference Butterfoss, Goodman and Wandersman 29 ) and literature suggests that community coalitions may achieve more than a single group or agency can achieve working in isolation( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ).

Most members identified that another purpose of the coalition was as a repository for evidence and information should funding arise. One member explained that they had referred to the coalition in successful funding proposals:

‘Every now and then you whip out a statistic or a food fact. You feel good that you’ve got data that you can stand behind.’ (Coalition member 6)

As an umbrella group, the coalition has enabled the coordination of grant applications and has minimised competition for funding.

The coalition has on occasion acted as a collective voice for advocacy, for example advocating for greater linkages to be made to community food security in a regional strategic food plan. Some members stated that they were bound by their own organisations’ rules, regulations and ‘red tape’ which hindered their own ability to advocate internally, therefore relied on the coalition to assume that role:

‘[The coalition] can go to government independent of the two [local governments] and say “we believe this is a real key issue”. So because it represents such a broad range of groups, strategically it’s logical to be that advocacy [role].’ (Coalition member 7)

The literature agrees that advocacy is often a core function of food policy coalitions( Reference Schiff 11 ); however, organisational representation and affiliations can constrain the types of advocacy members can engage in( Reference Siddiki, Carboni and Koski 6 ). Additionally, it has been noted that food system advocacy can often be narrow in scope, focusing on only one issue, due to issues of resource allocation( Reference Sadler, Arku and Gilliland 12 ).

Theme 4: coalition function is optimised through focused collaborative strategies

A survey of fifty-six food policy councils operating in the USA found that few had the same foci( Reference Siddiki, Carboni and Koski 6 ). Therefore, the types of strategies employed by a food policy coalition are generally unique to the particular setting and context. The ‘Implementation of Strategies’ construct of Community Coalition Action Theory states that ‘Coalitions are more likely to create change in community policies, practices, and environment when they direct interventions at multiple levels’( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ) (p. 165). Document analysis demonstrated a pronounced evolution for the coalition under study. During the first two years, meetings focused largely on information sharing and member updates regarding individual strategies. However, in the latter years there was a marked increase in the number of actions specific to the coalition, collaborative strategies between members, advocacy efforts and cross-shire initiatives.

Members described several factors which supported this evolution. Member attributes such as flexibility, patience, willingness, passion and enthusiasm were all commonly mentioned as enablers for creating an environment conducive to collaboration. Members stated that they generally enjoyed being at meetings, reflecting that a culture of openness and collaboration was generally encouraged:

‘I think the group is very comfortable about talking quite openly about things [and] that everybody’s quite happy to share.’ (Coalition member 9)

While observing a coalition meeting, the first author noted that a collegial atmosphere had been created.

There was general consensus that enthusiasm and momentum were optimised when members could focus on collaborative projects, rather than just reporting back at meetings as to what they were working on. Members reported appreciation for three task-focused meetings that were scheduled in addition to the regular meeting calendar, which allowed members to collaborate on specific strategies such as planning a regional food forum, developing an online regional food map and conceptualising the food system situational analysis project. During these task-focused meetings, members agreed to collaborate and contribute towards various aspects of the initiatives.

Document analysis revealed at least three examples of cross-jurisdictional initiatives that were not in existence prior to the coalition’s establishment, which included an interactive online directory demonstrating connections between local food producers, retailers and food enterprises in the region; an annual sustainability festival; and an agricultural climate change adaptation project. These strategies align closely with the common focus areas of North American food policy councils, which include local food production and distribution, food access, sustainable agriculture and environmental protection( Reference Siddiki, Carboni and Koski 6 ). Members attributed the coalition to the creation of these cross-jurisdictional initiatives, citing the coalition as a catalyst for creating strong links across the two government boundaries and fostering collaborative relationships between members representing diverse sectors such as sustainability, economic development and health:

‘Relationships have developed where we’ve ended up working in collaboration with [the other shire] on three projects now. All of those have really blossomed out of the Food Policy Coalition. It’s been fantastic, both [local government areas] are really positive about the cooperation and the collaboration that’s happening.’ (Coalition member 9)

This cross-jurisdictional way of working is important since many food and nutrition issues facing communities are likely to be a symptom of the broader food system, which is best addressed at a regional level.

It is evident that the collaborative task-focused meetings were well received and that more should be structured into the coalition’s schedule. As some members were more practically focused, a suggestion was to create a subgroup of the coalition where interested people at the local delivery level could collaborate on grassroots smaller-scale projects:

‘I think there needs to be a subgroup of the coalition that can work a little more effectively in a local hands-on way. I have some capacity … but [by myself] I won’t have any roar. I’ll just be a fairly meagre voice. But if you could combine with people from the local area with a common interest and they can work with their local community for local projects and gathering together, I think that gives … some strength.’ (Coalition member 6)

There was general agreement among members that the coalition should be focused at the political, strategic level and be advocating for systemic and policy change. However, some cautioned against losing the community voice, lamenting that creating a community groundswell was not a core focus of the group, despite its importance. Evidence suggests that it is usual for such tension to arise between the two working styles, therefore it has been recommended for food policy coalitions to create other networks or groups to focus on programme implementation which can feed into the broader food system efforts of the coalition( Reference Schiff 11 ).

Theme 5: sustainable food system policy change is a long-term pursuit

The last theme relates to a food policy coalition’s role in influencing a local food environment, particularly with regard to any changes to policy. Food policy can be defined as ‘any decision made by a government agency, business or organisation which affects how food is produced, processed, distributed, purchased or protected’( Reference Hamilton 35 ). However, a survey of fifty-six food policy councils operating in the USA found that there is not a common definition of what constitutes food policy( Reference Scherb, Palmer and Frattaroli 13 ). Evidence suggests that food policy coalitions can encounter difficulties when attempting to influence policy, therefore tend to focus more on programmatic work( Reference Schiff 11 ).

When members were asked what change had occurred since the coalition’s establishment, responses generally reflected changes in membership collaboration, raised awareness of others’ roles and capacity, ‘connectedness of members’ and change in direction of the coalition’s focus; rather than changes to the local food environment or system. Some members reported that with the coalition in place there had been shift in focus from food security for disadvantaged groups towards working at a broader systems level. This was also reflected in the document analysis described previously.

Document analysis revealed an authorising environment for broader food system work. Food and nutrition was present in several high-level strategic documents (such as local government health policies and visionary plans which list the region as a food bowl for the state), indicating that food is a pertinent issue for both governing bodies and the local community.

Document analysis revealed two occasions where the coalition had contributed towards changes to food system policies and regulations. These included the coalition advocating to local government which led to the creation of two policies allowing produce gardens to be established on local government-controlled land. This is an example of the food policy coalition’s role in increasing opportunities for local food production.

Members recognised that ‘policy’ can be defined broadly and can take many forms, from regulatory policy to influence local land use or institutional policy to affect school and workplace food environments. Some members explained that during the coalition’s early stages, there was little focus on policies within the members’ agencies (such as staff health and well-being policies, catering and vending machine policies); however, that had now increased in importance. One member gave an account of the situation in their own organisation:

‘There’s definitely a heightened awareness of Healthy Eating at [the organisation]. There’s now a staff health and well-being policy where we’ve included a line about improving access to healthy food in the workplace. So that wasn’t there in the past, and whilst this Food Policy Coalition didn’t directly write or have a meeting about that, I think our connection in this group has risen the profile of healthy eating.’ (Coalition member 3)

Evidence suggests that such policies can also positively shape a local food environment by facilitating access to healthier food options( Reference Scherb, Palmer and Frattaroli 13 ).

Several members reported that being part of the coalition had improved their knowledge of how policy could be influenced and that the coalition could potentially bolster change because the mechanism had been created to do so:

‘I’m not sure that the Food Policy Coalition’s changed [policy] but what they’ve done is provide support towards moving things forward to be brought into the policy realm.’ (Coalition member 11)

The general sentiment was that higher-level policy change is a longer-term goal and perhaps the coalition had not been around long enough to have had much of an influence to date. However, all participants agreed that the coalition should focus its efforts at the policy level.

One of the last constructs of Community Coalition Action Theory is ‘Community Change Outcomes’ which states that ‘by implementing interventions at multiple levels, coalitions are able to create change in communities that can reduce risk factors and increase protective factors’( Reference Butterfoss and Kegler 20 ) (p. 178). The case study has demonstrated that the food policy coalition has influenced strategies and policies which can shape a local food environment. Furthermore, the adopted action plan described in Theme 1 should enable coalition members to implement interventions at multiple levels and contribute towards sustainable food system policy change in the future.

Limitations

The current study employed qualitative practices such as data triangulation and researcher triangulation at the data analysis stage to enhance the rigour and trustworthiness of findings; however, some limitations to the chosen methodologies should be noted. The investigators originally sought to interview both past and present coalition members, but the final cohort included currently active members only. Feedback from past members may have added richness to the analysis by providing divergent viewpoints.

This is an example of a single case study which was selected to illustrate a particular issue( Reference Liamputtong 25 ), in this case how community coalitions can respond to local food system issues. These research findings are contextually unique, relevant to a specific time, place and experiences of stakeholders within this particular case( Reference Bryman and Teevan 36 ). For example, this model is unique to Victoria, Australia, therefore care must be taken if extrapolating findings to other food policy coalitions or contexts. Multiple case studies and further testing of theory are needed to understand the diverse functions of food policy coalitions and their ability to influence local food environments. This will enable a greater understanding of localised food system efforts, which may lead to their replication and eventually create opportunities for broader systemic food system change( Reference Purifoy 37 ).

Conclusion

Food policy coalitions are increasingly being established as a mechanism to address food system issues, yet there is limited evidence of how they operate in practice. The present case study found that the coalition’s function was optimised by its leadership structure, small-sized core membership and extensive community links. Its ability to remain responsive and relevant to the community context and being a focal point enabled members to engage in food system advocacy as well as pool efforts in an environment of limited funding.

The evolution of the coalition led to more collaborative cross-jurisdictional food system strategies and policies over time. While members generally recognised that structural food system change is a longer-term pursuit, the general sense was that the coalition was poised to focus future efforts towards working more in the policy realm. This case study demonstrates that with a sound structure and focus on collaborative strategies, food policy coalitions may be a mechanism to positively influence local food environments.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors wish to acknowledge the food policy coalition chair, Julia Lomas, and the coordinating agency for their role in facilitating data collection, recruiting study participants and providing documents for analysis. The authors would also like to thank and acknowledge the coalition members for participating in interviews, checking the authors’ interpretations of the data and for their dedication towards improving their local food environment. Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: J.M. and C.P. formulated the research questions and designed the study. J.M. designed the interview questions and carried out the data collection. J.M. and C.P. analysed the data and drafted the article. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethics approval was obtained from Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number CF14/2724-2014001514). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.