Matilda de Bailleul (d. 1212) was the daughter of Euphemia of St. Omer and Baldwin I, castellan of Bailleul in Flanders.Footnote 1 She died a childless widow; we know nothing about her husband. Her maternal grandfather was William II, castellan of St. Omer, a position held by members of the family for over 150 years since 1105.Footnote 2 Her maternal uncle, Osto, was a Templar who was based in Flanders and then England.Footnote 3 There is no direct evidence explaining Matilda's move ca. 1174 to Wherwell, a Benedictine abbey in Hampshire that was relatively prosperous throughout its history and was “almost certainly” founded in the tenth century by Queen Ælfthryth, wife of King Edgar.Footnote 4 However, both Wherwell and Matilda had numerous Anglo-Flemish connections that could explain her presence there. Two possible patrons have been proposed for the restoration of Wherwell and for Matilda's move there: (i) Queen Matilda (of Boulogne), wife of King Stephen; and (ii) Henry II.

In 1141, Wherwell was burnt to the ground, an act attributed to William of Ypres, the commander of Queen Matilda's Flemish mercenaries.Footnote 5 Queen Matilda's name surprisingly appears in the list of obits in the calendar of a psalter commissioned by Osto and later owned by Matilda de Bailleul (Cambridge, St. John's College, MS C.18, hereafter the Wherwell Psalter).Footnote 6 This has led to suggestions that Queen Matilda was behind the restoration of Wherwell, but there is no evidence of her having a direct connection with either Matilda de Bailleul or Wherwell itself, and in fact Queen Matilda was dead (d. 1152) by the time Matilda de Bailleul became abbess. Bucknill notes the possibility that Queen Matilda had some involvement in plans to rebuild Wherwell and that those plans only came to fruition after her death.Footnote 7 Bugyis, however, has argued that extant documents point to Henry II as the driving force behind the restoration of Wherwell and Matilda de Bailleul's move, perhaps via her uncle Osto's connection with Henry II.Footnote 8

Though we can only speculate on the reasons for Matilda's move, we know that her efforts to restore Wherwell were recognised by Pope Celestine III, who issued a privilege to Matilda and her consorors on May 21, 1194, in order to protect their community from plunder.Footnote 9 There is no evidence that it was issued in response to a particular threat at that time. From it we learn that Matilda remedied (amongst other things) the lack of books: “. . . through you those things that had been ordered badly there received arrangement and order, and the monastery, which had been destitute of both books and other ecclesiastical ornaments, received a welcome increase in all these things.”Footnote 10 Matilda is likely to have been personally wealthy and donated many of the items herself.Footnote 11 Books were a vital part of monastic life: Matilda's time as abbess no doubt had a profound impact on the literary life of the nuns. Her obituary in Wherwell's mid-fourteenth-century cartulary (London, BL, Egerton MS 2104a, hereafter the Wherwell Cartulary) likewise attests to her commitment to education: “So that doctrine and learning might not be deficient, the zealous mother acquired one hundred and six volumes of books.”Footnote 12 This was a significant donation. We know something of Matilda's niece, prioress, and successor, Euphemia de Walliers (or Wallers) (d. 1257), from her obituary in the Wherwell Cartulary: “Moreover, she was similarly attentive to external affairs and she conducted herself in her actions and her speech in such a way that she seemed to have not a feminine but rather a manly spirit.”Footnote 13

In this article I provide the first full edition, translation, and commentary for eleven elegiac couplets celebrating Matilda's life and for an epistola consolatoria (letter of consolation) from Prior Guy of Southwick Priory to Euphemia de Walliers. The texts appear on the final verso (fol. 12v) of St. Petersburg, National Library of Russia, MS Lat.Q.v.I.62 (hereafter Lat.Q.v.I.62). No one has hitherto provided a complete translation of the couplets. Gillert, Staerk, and Barratt have published a complete Latin text.Footnote 14 Miner includes the Latin text in an unpublished dissertation.Footnote 15 Gillert and Staerk both transcribe only the beginning and end of the letter of consolation.

Elegiac Couplets in Honor of Matilda de Bailleul

Authorship

Barratt raised the possibility that the couplets were written by one of the Wherwell nuns, perhaps even Euphemia.Footnote 16 The evidence is circumstantial and oblique, but nevertheless tantalizing. Firstly, Barratt highlights the emphasis on Matilda's role as a mater and matrona. Since Matilda was a mater to the nuns of Wherwell, it would make sense for one of the nuns (for example, Euphemia) to have written verses that stress those aspects of her life. However, it is worth noting that the term mater itself does not indicate that the author was a nun of Wherwell: even an outsider would have considered Matilda a mater to the nuns. Secondly, Barratt notes the Latin letter from Guy to Euphemia on the same folio: the fact that Guy corresponded with her in Latin suggests that she knew enough Latin to have written the couplets. This is evidence in favor of Euphemia having written the verses rather than an anonymous nun.

The authorship of the verses is complicated by the fact that they may belong to two different poems. Gillert's edition is the earliest known to me and takes the verses as one poem; Barratt treats them as one poem; Bucknill states that there are two poems; and Staerk's layout suggests that he believed the verses to constitute a single poem.Footnote 17 Miner prints the text as though a single poem, but notes that, if the first couplet is ignored, then “the poem appears to be more like two epitaphs, one of four distichs, one of six, each beginning with a line of alliterating m's and closing in traditional ways.”Footnote 18 In the manuscript, the couplets are split between two columns and seemingly presented as two poems, each beginning with a pen-flourished initial in red and blue ink.Footnote 19 There are five couplets in column one and six in column two.

Although Bucknill states that there are two poems, she does not entertain the possibility that they were written by different authors. There is, however, metrical evidence in favor of this conclusion. Firstly, the treatment of the name Matilda is inconsistent: Mātildis (I.3), but Mӑtildis (II.1).Footnote 20 This inconsistency could be explained by the difficulty of assigning a Latin scansion to a Germanic name. Names were often a source of difficulty in medieval Latin verse inscriptions.Footnote 21 However, such uncertainty would usually lead to some authors choosing Mātildis and others Mӑtildis, rather than one author vacillating between the two. Some useful evidence can be found in the mortuary roll of Matilda (d. 1113), abbess of La Trinité at Caen.Footnote 22 Numerous Latin forms of her name appear in the poems contained in the roll. Those forms that appear in quantitative verse show whether the first syllable was treated by the author as heavy or light. There are a total of forty-nine examples of the name with a heavy first syllable, thirty-two with a light first syllable.Footnote 23 The only example from the Low Countries in the roll is Māthildis (Ghent).Footnote 24 From France, we find thirty-three heavy and sixteen light; from England, fifteen heavy and sixteen light. Most poems contain only a single mention of the name, but ten use the name more than once. Just two poems account for twelve of the sixteen light examples from England, so the light scansion was perhaps not as common in England as it might seem. Matilda of Caen's mortuary roll therefore shows that the heavy scansion was generally more common.Footnote 25 There are examples of two poets from the same location using different scansions, but being internally consistent.Footnote 26 Interestingly, there are also examples of individual authors vacillating between the heavy and light scansions: three poems have this.Footnote 27 Since ten poems use the name more than once, the fact that three of them vacillate suggests that such inconsistency was not as rare as might have been thought.

It is possible that the different scansions in poems I and II reflect a difference between an author from the Low Countries and an author with a more Anglicised pronunciation of Matilda's name. The single heavy example from the Low Countries in Matilda of Caen's roll is clearly not enough evidence to show that the heavy scansion was more common there. If we expand our search to other texts, we later find spellings like the genitive Machtildis (Brabant, 1312), which would unavoidably scan with a heavy first syllable.Footnote 28 Latin forms attested in England as early as the twelfth century show spellings that begin Mati-, which is a spelling more compatible with a light first syllable, even though it does not guarantee one.Footnote 29 The evidence is currently weak, but further examples may come to light that show the heavy scansion to be associated with the Low Countries and the light scansion to be more common in England. Far more striking is the apparent difference between the treatment of the pentameter caesura in poems I and II. In poem I, the five pentameters never allow a short open vowel before the caesura. In poem II, this licence is found in three of the six pentameters: carne (II.1), pia (II.8), and extrema (II.10). It could, however, be a statistical fluke that all these examples appear in poem II, given the small number of pentameters across the two poems.

It is harder to draw reliable conclusions from the contents. The repetition of the date of Matilda's death (I.9–10 and II.9–10) may possibly be evidence that we are dealing with two separate poems, but certainly has no bearing on the question of whether there are two poets. At I.1–4 we find the only section with first person references: I.1–2 obliquely refers to the poet, while I.3–4 is a direct lament by the poet (molestor). Poem II has nothing comparable, which again suggests that there are two poems, but not necessarily two poets. The focus on personal grief in I.1–4 could suggest that poem I was written by someone with a particularly close connection to Matilda, namely her niece, Euphemia. Whilst poem I focuses on Matilda's life and death at Wherwell, poem II gives a brief biographical sketch, showing that there are two poems covering different aspects of her life.

Even though there is no single, definitive proof, the body of evidence points to two poems by two different authors. The most compelling arguments are metrical: the same author could easily have written two poems with different contents, but it would be unlikely for them to have adopted a different approach to the pentameter caesura in each poem. There are examples of a single poet using both scansions of Matilda's name, but it is more common for poets to stick with a single scansion. In poem I, the very personal lament is evidence in favor of Euphemia's authorship. It is possible that in poem I the scansion Mātildis and the more Classical approach to the pentameter caesura point to Continental (that is, Euphemia's) authorship, but more research is needed on regional variation in Latin poetry of this period. A brief examination of mortuary roll verses from English institutions in the early twelfth century provides similar examples of light syllables being allowed before the caesura in both hexameters and pentameters, though the practice is not common.Footnote 30 Many of these poems from England do not have it; a few poems have one or two examples. The frequency in poem II is therefore all the more remarkable.

The identification of poem I as Euphemia's work would leave poem II as the work of an anonymous poet, perhaps an English nun at Wherwell, but on this we can do little but speculate. It is not inconceivable that Guy of Southwick was the author. His letter of consolation to Euphemia (see below) indicates that his Latin was probably sufficient to write the verses. Furthermore, there is nothing in poem II that precludes his authorship. It is difficult to know whether certain aspects of poem II should be taken as indicative of male authorship, but it is worth noting the emphasis on Matilda being a virago and “a woman in sex only,” whilst “in habits and merits she was completely manly.” These were, however, common enough sentiments at the time and need not preclude female authorship (and therefore suggest male authorship).Footnote 31 At any rate, the only evidence for Guy's authorship is the fact that he was moved enough by Matilda's death to write to Euphemia, so he may also have honored Matilda with an epitaph.Footnote 32

Although a detailed discussion of female literacy in the Middle Ages is beyond the scope of this article, a few things should be said about the potential importance of the authorship of these verses for our understanding of female literacy in the thirteenth century. There has been a growing body of scholarship on elite female literacy and women as literary patrons (whether secular or monastic, Latin or vernacular).Footnote 33 Despite the rise of the vernacular in English convents in the thirteenth century, a few continued to use Latin to a greater degree than the majority.Footnote 34 It is noteworthy that Wherwell, with its two closely-related Flemish abbesses (Matilda and Euphemia), was one of the few exceptions. Both abbesses must have played an important role in the presence of Latin at Wherwell after its destruction.

Our evidence for Latin literacy at Wherwell under the Flemish abbesses relies heavily on the Wherwell Psalter and Lat.Q.v.I.62. Both have been discussed by Bugyis and Barratt.Footnote 35 The additions and alterations made to these manuscripts during the lifetimes of both Matilda and Euphemia suggest the presence of nuns literate in Latin. In this context the identification of two poets (not one), both possibly female, has important implications. It suggests that knowledge of Latin was not confined to the two abbesses: there was, instead, a culture of Latin literacy fostered by the teaching of these two outstanding abbesses. The Wherwell Cartulary's obituary for Euphemia, which may have been written by one of the nuns, could be evidence of their teaching's legacy.Footnote 36

Origin

Miner suggests that the opening couplet of poem I is “a personal expression of sorrow,” whilst the following lines (that is, I.3–10 and II.1–12) represent two epitaphs, which were written in order to give the nuns at Wherwell “a choice of verse for use on the actual tomb.”Footnote 37 The difficulty with this interpretation is the separation of I.1–2 from the rest of poem I, since molestor (I.3) continues the “personal expression of sorrow.” It is much easier to explain poem I as a single literary epitaph, perhaps by Euphemia, which mixes a personal lament with a celebration of Matilda's life, death, and afterlife.

Poem II, however, looks more like an epitaph specifically meant for Matilda's tomb. It bears strong similarities to other medieval verse epitaphs, for example, one written for the tomb of Bruno the Carthusian (d. 1101):

I who am buried under this stone deserved to become the first founder of Christ's fold in this monastery. My name is Bruno. My mother was Germany, but the heart-warming silence of the cloister brought me to Calabria. I was a teacher, a herald of Christ, a man known throughout the world. This was heavenly grace, not merit. The sixth day of October unlocked the chains of the flesh. You who are reading these lines, pray for peace for my soul.Footnote 38

Compare II.7–12 (honoring Matilda):

Flanders gave birth to her; England gave her a Rule; Wherwell gave her an end; her pious life allowed her to see God. The day after the feast of St. Lucy gave to this woman the beginnings of light, so that her final day is her first day. May God himself be the true day for her and a giver of peace, by perpetuating the day for her rest.Footnote 39

Both contain elements common to such poems, sketching out the basics of the deceased's life in a similar way: birth in one place, life in another, date of death, and prayer for peace for the soul in the afterlife.Footnote 40 Both are anonymous, as funerary inscriptions often are.Footnote 41 Poem I differs from both due to its first-person lament by the author. When funerary inscriptions speak in the first person, the voice is usually that of the deceased.Footnote 42

We know from Orderic Vitalis that colleagues and students of William of Fécamp composed verse epitaphs for William after his death.Footnote 43 Hildebert's epitaph was used for William's tomb, while Athelelm's was written in William's mortuary roll. A similar situation may have occurred at Wherwell: Euphemia wrote poem I for inclusion in a mortuary roll and another nun wrote poem II for use on Matilda's tomb. Both were then entered in the mortuary roll, perhaps along with Guy's letter of consolation. At around the same time, all three texts (the two poems and the letter) were copied into Lat.Q.v.I.62, perhaps from the mortuary roll before it departed Wherwell.

Manuscript

Thomson gives a full description of the manuscript, which I summarise here for convenience, since copies of his work can be hard to access.Footnote 44 It comprises two quires, each of which has six folios. He states that the first quire was definitely made at St. Albans in the middle of the twelfth century, whilst the second is of a later date and could have been added at Wherwell. Fols. 1r–6v (the first quire) contain the calendar; fols. 7r–10v computistic material; fols. 11r–12r musical material, including a Guidonian hand; and fol. 12v the texts relating to Matilda's death.Footnote 45 Thomson identifies numerous hands, but for the purposes of this article it is important to note that he attributes fol. 12v to a single scribe from the first half of the thirteenth century, not long after Matilda's death. The additions to the calendar by many different hands show that it (along with the second quire) was at Wherwell by the late twelfth century, where it remained until the early fourteenth century (at least). Fol. 12v is the only material that was clearly added at Wherwell. Everything else in the second quire could have been added at either St. Albans or Wherwell.

The three texts on fol. 12v are carefully laid out, suggesting a well-planned, single act of copying. Poem I (the first column) seems to have been written first. Afterwards, poem II (the second column) was added. The first line of poem II is almost identical in appearance to the text in poem I, but subsequent lines of poem II (in particular II.3 onwards) appear larger, as though the scribe decided that the original text size was too small. By placing poem I on the left and poem II (which is two lines longer) on the right, the scribe leaves a space of two lines beneath poem I, in which the rubric for the letter of consolation appears. This allows the letter to be written across the whole page without leaving any gaps.

The calendar, which was presumably originally attached to a psalter, had reached Wherwell by 1189 or soon afterwards.Footnote 46 How this transpired is not known. Thomson notes Eileen Power's suggestion that nunneries were generally dependent on male houses and professional scribes for their books; he therefore speculates that Wherwell may simply have ordered “its service-books from the nearest, most accommodating or most competent scriptorium.”Footnote 47 Bucknill suggests that there must have been a link (now obscure) between the Bailleul family and St. Albans: a private psalter was probably given to Euphemia in Flanders and then taken by her to Wherwell, with the calendar being the only part of the psalter now extant.Footnote 48

Edition

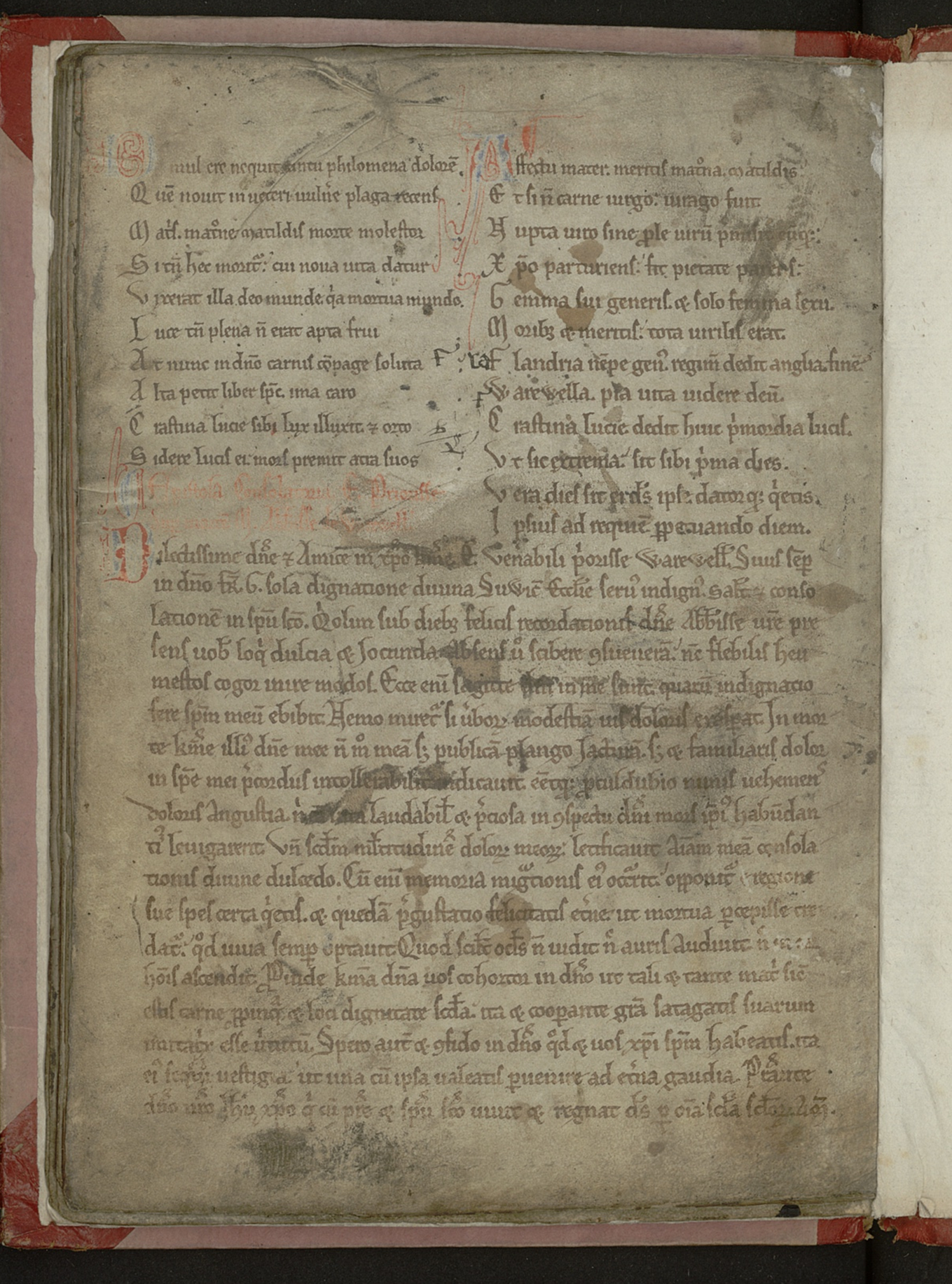

In the edition below, the use of punctuation and capital letters is in accordance with modern conventions. All abbreviations have been silently expanded. Square brackets surround letters that are completely illegible in the photograph (Figure 1) but can be supplied from the context.

Figure 1: St. Petersburg, National Library of Russia, MS Lat.Q.v.I.62, fol. 12v

Text

I

II

Translation

I

The nightingale cannot soothe with her song the pain which a recent blow renews in an old wound. I am troubled by the death of Matilda, matron mother, if however she is dead to whom a new life is given. [5] She lived a pure life for God because she was dead to the world; she was not, however, fit to enjoy the full light. But now that she is with the Lord and the bonds of the flesh have been broken, her free spirit seeks the heights, while her flesh seeks the depths. The day after the feast of St. Lucy shone upon her and, when the star of the morning has risen for her, black death crushes its allotted people.

II

In disposition a mother, by merits a matron, Matilda, although not a virgin in flesh, was a virago. She was married to a man without the offspring of men and she sent him ahead. Giving birth for Christ, she becomes a parent through her piety. [5] A jewel of her people and a woman in sex only, in habits and merits she was completely manly. Flanders gave birth to her; England gave her a Rule; Wherwell gave her an end; her pious life allowed her to see God. The day after the feast of St. Lucy gave to this woman the beginnings of light, so that her final day is her first day. May God himself be the true day for her and a giver of peace, by perpetuating the day for her rest.

Commentary

I.1 philomena: A common medieval spelling of philomela (“nightingale”): see DMLBS s.v. philomela.Footnote 49 The nightingale's connection with lamentation can be found as early as Homer (Od. 19.512–23), where Penelope compares her mourning with that of the ἀηδών (“nightingale”).Footnote 50 Latin philomela comes from Greek Φιλομήλα (Philomela), a princess in Greek mythology who (according to most Latin authors) was turned into a nightingale, whilst her sister, Procne (Πρόκνη), became a swallow. In some versions of the tale, Philomela becomes a swallow and Procne a nightingale. The version of the myth in Ovid (Met. 6.401–674) was the most widely known in the Middle Ages and influenced authors like Chrétien de Troyes and Chaucer, although Ovid (in his Metamorphoses) does not identify which birds the sisters become.Footnote 51 Ovid does, however, elsewhere associate Philomela with mourning (Am. 2.6.6–10), as does Vergil (G. 4.511–515), who compares Orpheus's lamentation after the loss of Eurydice to the mourning nightingale (maerens philomela). In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the nightingale suddenly appears as a favorite among poets throughout Europe.Footnote 52 Yet in Christian poetry the nightingale is mostly connected with consolation and joy rather than lamentation.Footnote 53 In the secular poetry of the Carmina Burana and in vernacular poetry, the nightingale is likewise usually associated with love and joy.Footnote 54 In I.1, the poet's grief is so great that even the joyful, soothing song of the nightingale cannot alleviate it.

D[e]mul[c]ere . . . [ca]ntu . . . dolorem: There are numerous Classical parallels that may have inspired this line, for example, the soothing birdsong in Vergil A. 7.32–34: “variae circumque supraque / adsuetae ripis volucres et fluminis alveo / aethera mulcebant cantu lucoque volabant.”Footnote 55 The alleviation of grief and pain was naturally a topos of pagan consolation literature. The consolation literature of pagan authors such as Cicero and Seneca the Younger subsequently influenced Christian authors such as Ambrose and Jerome.Footnote 56

I.2 nouat: The vowel quantity shows that this cannot be nōuit from noscere. Firstly, the couplet would make no sense: “The nightingale cannot soothe with her song the pain which a recent blow knows in an old wound.” Secondly, such a metrical anomaly would be unusual in a common verb, given that poem I otherwise has Classical quantities. Preference should therefore be given to an interpretation of nouit that would scan correctly. Gillert prints nouat as though it were the manuscript reading.Footnote 57 In the manuscript the reading nouit is clear, so this is probably a scribal error under the influence of the common perfect nouit (from noscere). I therefore emend the text and likewise read nouat from nouare (“to make new”): “the pain which a recent blow renews in an old wound.”

in ueteri uulnere plaga recens: Staerk has n̅e̅lu where the manuscript clearly reads uuln͑e. There do not seem to be any proposals identifying this “old wound.” The “recent blow” (plaga recens) is clear: the death of Matilda. The “old wound” may be the damage caused by the papal interdict issued by Innocent III in 1208, which was still in effect and several years “old” by the time Matilda died. Christian burials were not allowed until the interdict was lifted in 1214, so Matilda's death in 1212 was a painful reminder of the significant impact the interdict had on normal life: even an abbess could not receive a proper Christian burial.Footnote 58 Gervase, a contemporary and a monk of Christ Church Canterbury, referred to a dolor . . . immanis et angustia (“an immense pain and affliction”) that spread throughout England due to the interdict, with the dead buried in profane places rather than consecrated cemeteries.Footnote 59 Clearly the interdict made the stressful period following a death far worse, since the living were denied the solace and closure provided by a Christian burial. Every death must have renewed the anguish caused by the interdict. Peter of Blois once even wrote a letter of consolation to Matilda regarding the interdict.Footnote 60

matris: As abbess she was the “mother” of the nuns at Wherwell. Bede uses mater to distinguish between abbesses and other women religious, for example, mater ancillarum and uirginum Deo deuotarum perplurium mater uirgo.Footnote 61

I.3 matrone: Matilda's status as a matrona (“married woman”) is explained in II.1–3 (see below).

morte molestor: The author expresses personal pain at the death of Matilda. Instead of beginning with a focus on Matilda, the poem opens with the poet's grief, reflecting the depth of the poet's sorrow and suggesting a very personal connection with Matilda.

I.6 luce tamen plena non erat apta frui: Although Matilda was, during her lifetime, “dead to the world” (mortua mundo) and living only for God, she was not able to enjoy the “full light” (luce . . . plena). However, after death (the transition is marked by At nunc) her spirit “seeks the heights” (alta petit), where she can now enjoy the “full light.” God is the full light. Compare 1 John 1:5: “quoniam Deus lux est, et tenebrae in eo non sunt ullae.” A few decades after Matilda's death, Thomas Aquinas, citing 1 John 1:5 in his commentary on Peter Lombard's Sentences, uses lux plena to describe God. He argues (Book 2, Distinction 12, Article 3) that, since God is the full light, knowledge of God himself in himself is the full light: “Cum autem Deus sit lux plena, et tenebrae in eo non sint ullae, 1 Joan. 1, cognitio ipsius Dei in se est plena lux.” Compare also the ideas of perfect knowledge and seeing face-to-face found in 1 Cor. 13:9–12.

I.9 Crastina Lucie . . . lux: Compare I.9–10 and II.9–10, both of which state the date of Matilda's death. See DMLBS s.v. crastinus (2b) for examples of crastinus used as a masculine substantive with a saint in the genitive to mean “the day after the feast of St. . . .” See DMLBS s.v. crastinus (1c) for both feminine and masculine examples of its use as an adjective with dies, again with the same meaning, “the day after.” Crastina Lucie . . . lux clearly means “the day after the feast of St. Lucy.” Note the play on the similarities between lux, lucis, and Lucie. Bucknill takes this to mean that Matilda died on December 14, since St. Lucy's day is December 13. Barratt instead takes the verses to mean that she died “on the morning of the Feast of St. Lucy (December 13).”Footnote 62 St. Lucy's day is December 13, so we might expect “the day after St. Lucy's day” to mean December 14, but perhaps the poetic reference is based on the day (whether liturgical or secular) beginning during the hours of darkness. Thus “tomorrow's light” (crastina lux) could be a reference to sunrise on December 13, since that is the daylight that follows the beginning of St. Lucy's day, which occurs at night. The obits for Matilda are frustratingly contradictory. The Wherwell Psalter has her death on December 13, but Lat.Q.v.I.62, fol. 6v, marks her obit on December 14.Footnote 63 Perhaps December 13 is correct and December 14 in the obit in Lat.Q.v.I.62 is a misunderstanding of the poetic references to her death in the same manuscript. If December 14 is correct, then perhaps the December 13 obit in the Wherwell Psalter is similarly a misunderstanding of the same poetic references and evidence that the scribe had seen verses like the ones in Lat.Q.v.I.62.

I.9–10 orto / sidere lucis: When the morning star (sidere lucis) has risen. Compare the ancient hymn Iam lucis orto sidere (“Now that the morning star has risen”). The hymn is sung at Prime and may have been part of the Old Hymnal, which means that it could date back to the fifth century.Footnote 64 It is found in eighth-century manuscripts at Darmstadt and Trier, whilst attestations in English manuscripts date from at least the eleventh century.Footnote 65

I.9–10 sibi . . . ei . . . suos: The intended referents of these pronominal forms are not all self-evident, because in Medieval Latin we find non-reflexive uses of se and suus as well as reflexive uses of is. In such close proximity it is not impossible to have sibi and ei both referring to Matilda, given the Medieval Latin extension of sibi to non-reflexive uses. Compare a poem from Chester in Bruno's mortuary roll, which has Gratia summa dei propitietur ei (line 6 of the poem) and then sit sibi iam requies (line 10): both ei and sibi refer to Bruno, but sibi conveniently creates a heavy syllable in sit, whereas ei allows propitietur to have a light final syllable.Footnote 66 This may also be the motivation for sibi in I.9, where ei would not scan. Note that suos is reflexive, referring back to death: “black death crushes its allotted people,” that is, death takes those whose time has come.Footnote 67 Since the dead are buried beneath the earth, they are also “pressed down” literally: see “Mors premit omne caput” (from Bruno's mortuary roll); “mors premit omnia” (twelfth century, Bernard of Cluny, De contemptu mundi 3.231).Footnote 68

I.10 mors . . . atra: In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, as in earlier times, mors is often given the epithet atra. Other common epithets during this period include fera, cita, dura, inimica, pallida, inuida, and amara, whilst improba, impia, mala, and crudelis are usually avoided.Footnote 69

II.1 Affectu mater, meritis matrona Matildis: The poet states that Matilda was a mother (mater) to the nuns at Wherwell in terms of the affection she showed them, but of course she was also their mater because she was their abbess (see above). She earned the status of matron (matrona, “married woman”) due to her marriage (see II.3), even though by the time she entered Wherwell she was a widow.Footnote 70

II.2 etsi non carne uirgo, uirago fuit: Due to her marriage she was not physically a virgin, but she was a uirago. The word-play on uirgo and uirago is common enough, and uirago was frequently used to commend women in the Middle Ages.Footnote 71 The sentiments expressed are common in medieval hagiography and are by no means a reason to presume male authorship.Footnote 72 Matilda was called a “noble and wise virago” (nobilis sapiensque uirago) who transcended “the minds of strong men in constancy and counsel” (fortiumque uirorum animos constantia et consilio transcendatis) during her lifetime in a letter sent to her by Peter of Blois, archdeacon of London, and written sometime between March 23, 1208 and January 1209.Footnote 73 Matilda's niece, Euphemia, was similarly praised for her “manly spirit” in her obituary in the Wherwell Cartulary: “that she seemed to have not a feminine but rather a manly spirit” (ut non femineum sed uirile magis animum gerere uideretur).Footnote 74

II.3 Nupta uiro sine prole uirum premisit eumque: Bucknill has a gap in the Latin here and, consequently, a gap in the English: “Married to a man, without children [ . . . ]” (“Nupta uiro sine prole uirum [ . . . ]”).Footnote 75 With sine prole uirum, compare Vergil A. 6.784: “felix prole virum” (“blessed in a brood of heroes,” referring to Rome), in which the old form of the genitive plural is preserved.Footnote 76 Our author no doubt copied prole uirum, either directly from the Aeneid or indirectly from another author. This line is our evidence that Matilda was a widow and did not have any children; or rather she did not have any surviving children when she entered Wherwell.

premisit: The use of praemittere (“to send in front or in advance”) as a euphemism for death is not specifically recorded in the DMLBS or the Oxford Latin Dictionary, but ThLL cites this meaning and gives examples. See ThLL s.v. praemitto I.B.1.a. Compare, for example, Seneca, Ep. 99.7: “quem putas perisse, praemissus est.”Footnote 77 The active sometimes implies responsibility. Compare Plautus Cas. 448: “certum est, hunc Accheruntem praemittam prius.”Footnote 78 In II.3, however, the use of the active (“she sent him ahead”) clearly does not mean that Matilda was in any way responsible for his death. For similar examples, see ThLL s.v. praemitto I.B.1.a.β, for example, Seneca, Dial. 6.19.1: “Iudicemus illos abesse et nosmet ipsi fallamus, dimisimus illos, immo consecuturi praemisimus.”Footnote 79 The Senecan passages found favor with Christian writers affirming a belief in the afterlife. We find an identical use of premisit in an entry from England in the mortuary roll for Vitalis, abbot of Savigny (d. September 16, 1122): “Multos ad summi premisit gaudia cęli, / Quos tandem sequitur, cum sanctis luce potitur.”Footnote 80

premisit eumque: Gillert and Miner punctuate “premisit, eumque / Christo parturiens.” This would reflect the usual syntax and word order with -que, but the sense would be difficult. The text would then read “Nupta uiro sine prole uirum premisit, eumque / Christo parturiens fit pietate parens” (“married to a man, she sent the man ahead without offspring and, giving birth to him for Christ, she becomes a parent through her piety”), suggesting that she gave birth to her husband for Christ in some manner of speaking. It would also make uirum the accusative object of premisit, removing the parallel with prole uirum in the Aeneid (see above). Barratt has no comma and instead a semicolon after eumque. The manuscript has a punctus elevatus after eumque. This makes better sense: -que can be postponed in poetry and premisit then governs eum. If a past tense of esse is understood with “nupta uiro,” then the whole line can be construed thus: “[She was] married to a man without the offspring of men and she sent him ahead.”

II.4 Christo parturiens fit pietate parens: The notion of the “bride of Christ” did not just apply to virgin nuns: married women (even those whose husbands were still alive) could also be brides of Christ.Footnote 81 Even a widow with children could become a bride of Christ.Footnote 82 Matilda may have been considered to have given birth for Christ by spiritually “producing” children in the form of nuns, thus making the nuns both brides of Christ and the “children” of a bride of Christ.Footnote 83 Compare, however, the twelfth-century Speculum Virginum 5.10: “Imitate this chief of virgins as far as possible, virgin of Christ, and you too, with Mary, will seem to give birth spiritually to the Son of God.”Footnote 84 We might therefore expect Matilda, as in the Speculum Virginum, to be portrayed as giving birth spiritually to the Son of God, not the nuns, via her piety. Yet the dative Christo shows that the author has in mind “for / on behalf of Christ.” Thus, in II.4 Matilda is not “giving birth to Christ,” which would require an accusative Christum. The search for an object for parturiens is perhaps the reason for Gillert taking “eumque / Christo parturiens” together. The conception of various kinds of spiritual kinship probably originates in John 1:12–13: “Quotquot autem receperunt eum, dedit eis potestatem filios Dei fieri, his qui credunt in nomine ejus: qui non ex sanguinibus, neque ex voluntate carnis, neque ex voluntate viri, sed ex Deo nati sunt.”Footnote 85 Aldhelm (in his prose De Virginitate) described the nuns taught by Hildelith, abbess of Barking (c. 700), as “adoptive daughters of regenerative grace brought forth from the fecund womb of ecclesiastical conception through the seed of the spiritual Word.”Footnote 86

II.5 gemma sui generis: Bucknill translates “jewel of her race”; Bugyis “jewel of her people.”Footnote 87 She is a jewel of the Flemish, as is made clear two lines later (II.7), where genus is also used: “Flanders gave birth to her” (“Flandria nempe genus . . . dedit”).Footnote 88

II.6 tota: Staerk erroneously transcribes totā (that is, an abbreviation of totam).

II.7 Flandria: Bucknill has La Flandria.Footnote 89 Although la is written before Flandria, it is clearly a later addition made in a different ink. In between the two columns there are several jottings. To the left of Flandria we find another F and then la. To the bottom left of Warewella (II.7) we find another F, and to the bottom left of that are a couple of indistinct letters. The presence of the F before la suggests that the scribe was scribbling Fla; the fact that these letters appear near Flandria indicates that this was the word the scribe had in mind. It may be part of a probatio pennae (pen trial). It is interesting that the scribe has chosen to fixate on Flandria.

regimen dedit Anglia: England gave Matilda the monastic rule under which she lived at Wherwell. See DMLBS s.v. regimen 7 for the meaning “rule of conduct (as observed by a religious community).” Note that regimen is perhaps a metrically-convenient alternative for rēgŭla (particularly in this context, since the accusative regulam would only ever be permissible in elegiacs via elision). The poem draws attention to the fact that Matilda's first experience of monastic life was in England.

II.7–8 finem / Warewella: Bucknill translates finem as “fulfilment.”Footnote 90 It could also mean that Wherwell gave her a goal/purpose in life; or it could simply highlight the fact that she died at Wherwell. II.7–8 seem to present a sequence: she was born in Flanders, entered the monastic world and lived under the rule in England, died at Wherwell, and saw God in the afterlife; these lines therefore cover her birth, life, death, and afterlife. This latter explanation seems the most plausible.

II.8 pia uita uidere Deum: Though piā scans as heavy at the pentameter caesura, the vowel is short by nature and pia agrees with uita, the subject of dedit, which must be understood from the previous line. The object of dedit is then the infinitive uidere: her pious life “gave seeing God,” that is, allowed her to see God upon her death. Neither Barratt nor Bucknill punctuates at the end of the line.

II.9 Crastina Lucie: See above on I.9: we should probably supply lux with Crastina.Footnote 91

huic: “to this woman,” that is, Matilda.

primordia lucis: The poet emphasises the etymological wordplay between Lucie and lucis by their placement at the caesura and the end of the line. The connection between these two positions in the hexameter is underlined in Leonine verse by the presence of rhymes, but the connection predates the use of rhymes. We might expect to see mention of Lucifer, continuing the wordplay, but perhaps the poet eschewed the male Lucifer, given feminine lucis and Lucie. Matilda died on the day after the feast of St. Lucy (compare I.9–10), so that was the day on which she saw the light of God, that is, entered the afterlife. Compare the same position in a hexameter by Prudentius: Hamartigenia 344: “antiquae recolens primordia lucis.”Footnote 92

II.10 ut . . . prima dies: Here ut introduces the result of the previous line. Her death marked her passage into the afterlife, so in a way her final day was nevertheless her first day, because it was the first day of her new life. Barratt mistakenly takes this to mean that Matilda died on the same day of the year on which she was born.Footnote 93 Compare Godfrey of Winchester (d. 1107) De Cnuth rege (from his Epigrammata historica) 11–12: “Lux postrema sibi luxit duodena Novembris, / et postrema dies fit sibi prima dies.”Footnote 94

II.11–12 Vera . . . diem: Staerk centres this couplet as though it were the final couplet of a single poem spanning the two columns. In reality it is the final couplet of the poem in the column on the right.

II.11 ei deus: Gillert reads er and then signals that the text is illegible up to ipse. Staerk transliterates erds. Though the letter looks like an r at a distance, enlarging a digital image shows that there is a separate black mark (not the same colour as the text) at the top right of an i. This has caused the confusion. Barratt has the correct reading, ei deus.

II.11 Vera dies sit ei deus ipse: Light and day are intertwined, and so day can stand for light. God is light (1 John 1:5) and Jesus calls himself the light of the world (John 8:12 and 9:5). Compare especially John 1:9: “Erat lux vera, quae illuminat omnem hominem venientem in hunc mundum.”Footnote 95 See also the twelfth–century Flemish-born Alain de Lille (Alanus de Insulis, Alan of Lille), Anticlaudianus 4.288–90: “Hos Deus esse deos fecit, quos lumine uero / Vera dies fudit et quos ab origine prima / Vestiuit deitatis honos”; and (in medieval hymns) “in carnis latebris / uera dies diescit” and “uera dies elucescit.”Footnote 96 Jesus is the “vera dies” at the beginning of a hexameter in Thietmar of Merseburg's early eleventh-century Chronicon (book 6, prologue, line 6): “Vera dies, lucem tu nunc benedicito talem.”Footnote 97

II.12 ipsius ad requiem perpetuando diem: Poems in mortuary rolls frequently end with prayers that the deceased be granted eternal rest. Here “by perpetuating the day for her rest” means “by granting her eternal rest.”

A Letter of Consolation from Guy of Southwick to Euphemia, Prioress of Wherwell

Guy was a canon of Merton and prior of the Augustinian priory in Southwick, Hampshire ca. 1186–1206.Footnote 98 The letter was obviously written after Matilda's death (December 13 or 14, 1212), but it cannot have been very long afterwards: Euphemia is still addressed as the prioress of Wherwell, so it must have been before she became the abbess, which cannot have happened earlier than July 28, 1213.Footnote 99 Preceding the letter are two lines of rubric introducing the letter. This rubric forms the last two lines of the first column of fol. 12v. The text of the letter then begins on the line below the rubric and the page is no longer split into two columns. In the edition below, section numbers have been added in square brackets in both the text and translation. The abbreviations for Iesu and Christo/Christi have been expanded; all other abbreviations have been silently expanded, with the exception of the names of the sender, the addressee, and the deceased. Guy (the sender) is represented only by G, so the remainder is supplied in brackets; the same is done for Euphemia (the addressee) and Matilda (the deceased). The use of punctuation and capital letters is in accordance with modern conventions. Letters that on their own are only partially legible, but are clear from the context, have dots beneath them. Sometimes words or letters are now completely illegible but can be supplied because they occur within quotations from other sources: these words/letters are placed in square brackets in the text. In the translation, square brackets are only used for the verb in the salutatio, which is omitted (as is usual) in the Latin. Quotations from the Bible and other sources are noted in the commentary but are not italicised or otherwise marked in the text.

Text

[Rubric:] Epistola consolatoria E(uphemie) priorisse super mortem M(atildis) abbatisse de Warewella

[1] Dilectissime domine et amice in Christo karissime E(uphemie) uenerabili priorisse Warewelle suus semper in domino frater G(uido) sola dignatione diuina Suwice ecclesie seruus indignus salutem et consolationem in spiritu sancto. [2] Qui olim sub diebus felicis recordationis domine abbatisse uestre presens uobis loqui dulcia et iocunda absens uobis scribere consueueram, nunc flebilis heu mestos cogor inire modos. [3] Ecce enim sagitte domini in me sunt, quarum indignatio fere spiritum meum ebibit. [4] Nemo miretur si uerborum modestiam uis doloris exasperat. [5] In morte karissime illius domine mee non modo meam sed publicam plango iacturam; sed et familiaris dolor in spiritus mei precordiis intollerabilit[er ra]dicauit, essetque procul dubio nimis uehemens doloris angustia, nisi eam ụịta laudabilis et preciosa in conspectu domini mors ipsius habundantius leuigarent. [6] Vnde secundum multitudinem dolorum meorum letificauit animam meam consolationis diuine dulcedo. [7] Cum enim memoria migrationis eius occurrit, opponitur e regione sue spes certa quietis et quedam pregustatio delicitatis eterne, ut mortua percepisse cṛẹdatur quod uiua semper optauit. [8] Quod scilicet oculus non uidit nec auris audiuit nec [in cor] hominis ascendit. [9] Proinde, karissima domina, uos cohortor in domino ut tali et tante matri, sicut estis carne propinqua et loci dignitate secunda, ita et cooperante gratia satagatis suarum imitatrix esse uirtutum. [10] Spero autem et confido in domino quod et uos Christi spiritum habeatis, ita eius sequamini uestigia, ut una cum ipsa ualeatis peruenire ad eterna gaudia. [11] Prestante domino nostro Iesu Christo, qui cum patre et spiritu sancto uiuit et regnat, deus, per omnia secula seculorum. Amen.

Translation

[Rubric:] Letter of consolation to Euphemia, prioress, regarding the death of Matilda, abbess of Wherwell

[1] To the beloved lady and friend in Christ, dearest Euphemia, the venerable prioress of Wherwell, Guy, always her brother in the Lord, by divine grace alone an unworthy servant of Southwick Church, [sends] greetings and consolation in the Holy Spirit. [2] Once, in the days of the blessed memory of the lady, your abbess, I was accustomed to say pleasant things to you when I was present and to write cheerful things to you when I was absent, but now tearful, alas, I must begin sad songs. [3] For behold, the arrows of the Lord are in me, and their poison almost consumes my spirit. [4] Let no one be surprised if the force of grief roughens the modesty of my words. [5] In the death of that dearest lady of mine I lament not only my loss, but also the public loss; but intimate grief too has unendurably taken root in the depths of my spirit, and without doubt the anguish of grief would be too strong, if the praiseworthy life and precious (in the eyes of the Lord) death of that woman were not greatly alleviating it. [6] Therefore, the sweetness of divine consolation has given joy to my soul in accordance with the multitude of my griefs. [7] For when the memory of the passing of that woman comes to mind, the sure hope of rest and a certain foretaste of eternal delight are set directly against it, so that she is believed to have acquired upon death that which she always wished for whilst alive; [8] which, of course, the eye has not seen, nor the ear heard, and which has not entered into the heart of man. [9] Therefore, dearest lady, I encourage you in the Lord that, with the support of grace, you strive to be an imitator of the virtues of such and so great a mother, just as you are a relative by blood and second in rank at the abbey. [10] Moreover I hope and trust in the Lord that you have the Spirit of Christ and follow his footsteps, so that like her you are able to arrive at the eternal joys. [11] With the help of our Lord Jesus Christ, who with the Father and the Holy Spirit lives and reigns, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Commentary

1 Dilectissime: The letter begins with a small pen-flourished initial in red and blue ink.

E(uphemie) uenerabili priorisse Warewelle: Euphemia is not addressed as the abbess, suggesting that the letter was written not long after Matilda's death (December 13 or 14, 1212).

Suwice ecclesie: Guy was prior of Southwick. Modern Southwick is spelled in various ways in charters and deeds: Suwic, Suthwyk, Suthwick, Suthweek, Sudwica, and Suthwike.Footnote 100

2 Qui olim . . . inire modos: Compare Boethius De consolatione philosophiae book 1, poem 1, lines 1–2: “Carmina qui quondam studio florente peregi, / Flebilis heu maestos cogor inire modos.”Footnote 101 Guy reworks and expands the first line liberally, but it is still clear that “qui olim . . . dulcia et iocunda . . . scribere consueueram” echoes “carmina qui quondam studio florente peregi.” The second line of Boethius is quoted verbatim. Guy explicitly states that he corresponded, met, and spoke with Euphemia in person during Matilda's lifetime. Bucknill suggests that Guy, Matilda, and Euphemia “talked and laughed together.”Footnote 102 Presumably she takes “uobis loqui” as referring to Euphemia and Matilda, but compare “abbatisse uestre” and “uobis scribere.” Guy is less likely to have written a letter jointly addressed to Matilda and Euphemia, so uobis probably refers to Euphemia alone. I think that here Guy is referring only to his previous conversations and correspondence with Euphemia.

3 ecce enim . . . meum ebibit: Almost a verbatim quotation of Job 6:4 “quia sagittae Domini in me sunt, quarum indignatio ebibit spiritum meum.”Footnote 103 Guy adds fere and moves the verb ebibit to the end of its clause. The abbreviation dni for domini is just about visible; it is anyway guaranteed by the context. I follow most biblical translations by rendering indignatio as “poison.” Most English translations of Job 6:4 make “my spirit” the grammatical subject and “their poison” the object (that is, the reverse of the Latin) for the sake of clarity, but my translation of Guy's letter is more literal.

3–5 ecce enim . . . intollerabilit[er ra]dicauit: This entire section is almost identical to part of a letter from Peter of Blois to Pope Celestine III (reigned 1191–1198), written ca. 1193: “Nemo ergo miretur si uerborum modestiam uis doloris exasperet; iacturam enim plango publicam sed et familiaris dolor in spiritus mei precordiis intolerabiliter radicauit. Sagitte enim domini in me sunt, quarum indignatio ebibit spiritum meum.”Footnote 104 Note how Guy's addition of “non modo meam” is somewhat clumsy given the following “sed et.” Peter's sentence contrasts publicam with familiaris, hence the use of sed. By adding “non modo meam” Guy preempts familiaris. Peter's letter is written in the name of Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, asking Pope Celestine III to intervene and press for the release of Richard I (the Lionheart), who had been taken prisoner near Vienna by Duke Leopold of Austria in December 1192 and handed over to Henry VI, the Holy Roman Emperor. Richard was released in February 1194.Footnote 105 From this the probable date of 1193 can be deduced. I can find no common source from which both Peter and Guy could have taken the non-biblical parts of this section. Since Peter's letter was written before Guy's, the obvious conclusion is that Guy had seen a copy of Peter's letter. Of course, the quotation from the Bible (Job 6:4: sagittae . . . meum) could have been chosen independently by each author, but the non-biblical sections suggest that Guy copied this whole passage from Peter's letter, including the choice of Job 6:4. We know that Guy corresponded with Peter.Footnote 106 While Matilda was alive, Peter of Blois, then archdeacon of London, sent Matilda a letter of consolation regarding the interdict Pope Innocent III had placed on England and Wales.Footnote 107 Peter's letter to Matilda was written at some point between March 23, 1208 and January 1209.Footnote 108 The numerous connections between Peter, Guy, Matilda, and Euphemia together make it believable that Guy had access to Peter's letter to Pope Celestine III and mined it for material when writing to Euphemia. The alternative is that both Peter and Guy borrowed from a source that is no longer extant, for example, a work by John of Salisbury: Guy made a florilegium of the letters of John of Salisbury, whom Peter of Blois also knew and from whose works Peter borrowed.Footnote 109

5 intollerabilit[er ra]dicauit: A small portion is not visible in the manuscript, but is guaranteed by the context and a comparison with Peter's letter to Pope Celestine III (see above on sections 3–5).

Nisi eam ụịta laudabilis et preciosa in conspectu Domini mors ipsius: Compare Ps. 115:6: “pretiosa est in conspectu Domini mors sanctorum eius.”Footnote 110 Aelred of Rievaulx (1110–1167) juxtaposes the uita laudabilis and mors pretiosa in three works: (i) De spiritali amicitia 2.14: “ut et eorum vita laudabilis, et mors pretiosa iudicetur,” which draws on both Ps. 115:6 and Cicero, De amicitia 23: “ex quo illorum beata mors videtur, horum vita laudabilis”;Footnote 111 (ii) Vita sancti Ædwardi regis 1.47–48: “laudabilis eorum uita et mors nichilominus preciosa”;Footnote 112 and (iii) Speculum charitatis 1.99: “neque enim tua mors flenda est, quam tam laudabilis, tam amabilis, tam omnibus grata vita praecessit.”Footnote 113 The reading ụịta relies mostly on the context, though the first two letters are just about visible. Aelred's work was certainly known to Peter of Blois, whose De amicitia christiana made use of Aelred's De spiritali amicitia.Footnote 114 It is plausible that Guy also made use of Aelred's work.

habundantius: Literally “more abundantly.”

6 unde secundum . . . diuine dulcedo: Compare Ps. 93:19: “secundum multitudinem dolorum meorum in corde meo consolationes tuae laetificaverunt animam meam.”Footnote 115

8 quod scilicet oculus . . . ascendit: Compare 1 Cor. 2:9: “sed sicut scriptum est quod oculus non vidit nec auris audivit nec in cor hominis ascendit quae praeparavit Deus his qui diligunt illum.”Footnote 116 The quotation from Corinthians allows us to supply [in cor], which is otherwise illegible.

9 loci: Here referring to Wherwell.

10 uos Christi spiritum habeatis: See Rom. 8:9: “si quis autem Spiritum Christi non habet, hic non est eius.”Footnote 117

ita eius sequamini uestigia: See 1 Pet. 2:21: “in hoc enim vocati estis quia et Christus passus est pro vobis vobis relinquens exemplum ut sequamini vestigia eius” and Job 23:11: “vestigia eius secutus est pes meus.”Footnote 118