Introduction

On 15 March 1993, a group of 12 artists occupied a large school building, Haagweg 4, in the Dutch city of Leiden, a mid-sized city of approximately 110,000 inhabitants in the vicinity of The Hague (20 km) and Amsterdam (45 km).Footnote 1 The group wanted to repurpose the class rooms into work and exhibition spaces, and demanded the building be bought and the occupation legalized by the municipality. In a retrospective account, one of the artists stated: ‘We did not want to be seen as squatters, but as artists.’Footnote 2 The group in particular distanced themselves from one other group of squatters: British and Irish youths. Shortly after the occupation, one of the artists stated: ‘Had we not squatted this place, a group of English squatters from the Parmentiercomplex [which was threatened with eviction] would have come here. And then the place would have been trashed.’Footnote 3 The tactic seemed to work out well for the group of artists. Two years after their action, Leiden's mayor Cees Goekoop referred to Haagweg 4 as an example of ‘how a building that has been written-off can still get a useful function’.Footnote 4 Two squats occupied by English-speaking squatters, however, were highlighted by Goekoop as counter-examples, given the ‘very unhygienic situations’ that reigned there. After years of struggle, Haagweg 4 was bought by the municipality, renovated and in 2010 given to the artist-owned Stichting Werk en Onderneming (Foundation for Work and Enterprise).Footnote 5

This short anecdote illustrates both the value that squatters assigned to their image and reputation – the artists of Haagweg 4 did not want to be seen as squatters – and the fact that the British and Irish squatters enjoyed a particularly bad reputation in Leiden. Often referred to as ‘the English’ or as ‘English squatters’ – although the group consisted of English, Scots, Irish and Welshmen – these squatters formed a sizable and visible community in Leiden during the early 1990s. In this era, several hundreds of youths travelled from the UK and the Irish Republic to Leiden and the surrounding villages to work as seasonal labourers in the floral industry.Footnote 6 Because it was hard for these youths to gain access to regular housing, they settled in holiday homes, on camping sites or in squatted houses. The squats soon formed the nexus of a lively subculture of raves and house parties. Not all of them squatted, however, and not all squatters were active in the rave scene.

Labour migration and housing conflicts in the 1990s are an understudied topic in Dutch migration history, which has mainly focused on the social integration of Moroccan and Turkish labour migrants who had arrived in the 1960s and 1970s.Footnote 7 As labour migrants, however, British and Irish youths in the 1990s faced a very similar situation: they were employed as manual labourers, struggled with a language barrier, were expected to stay only temporarily and as a result of all the above had special difficulties in finding proper housing. Leiden had attracted several hundreds of migrant workers in the 1960s and 1970s, and the resulting housing problems had even led some of them to take to squatting. In 1978, Turks had found refuge and opened two cafés in the derelict and abandoned printing works of the Rotogravure company, and in 1979, Moroccans occupied the cultural centre Morspoortkazerne for several days to demand regular rent contracts.Footnote 8 Although the situation of the English-speaking squatters was different in some respects – they were white, had passports and could more easily return home – their housing struggles show that labour migration after 1945, and its related conflicts, have a continuous history that runs into the present, when east European migrants face similar problems.

Leiden has a long history of migration.Footnote 9 In the seventeenth century, it had attracted both labour migrants and people fleeing religious persecution. During the eighteenth century, economic decline turned the city into a site of emigration. The next wave of immigration came in the post-war era, as the economy grew again. During the 1990s, the Green Party joined the city government and started a campaign branding Leiden as a ‘city of refugees’, emphasizing the city's welcoming and tolerant nature. By this time, Leiden was a mid-sized city,Footnote 10 which fulfilled a regional role as an economic centre. While its urban setting created space for anonymous crowds of youths to roam the city, this could never occur on a scale that could elicit large-scale escalations as in Amsterdam or Rotterdam. In fact, most issues were pacified through conversations and negotiations, and the local authorities were invested in de-escalation. Conflicts involving foreign squatters were thus to a large part influenced by Leiden's role as a ‘typical’ mid-sized city, but with specific local characteristics. These included the city's large student population and its location close to the agrarian ‘bulb region’, known for its floral industry. The former influenced its liberal political and policing culture, while the latter attracted migrant workers.

Research on squatting has traditionally focused on squatter movements in specific cities.Footnote 11 Squatters, however, were very mobile and easily moved between cities. The squatters’ travel networks have only recently become a topic of historical research. Such research, however, mainly focuses on the transnational networks of political squatters and the exchange of action repertoires, ideologies and political cultures.Footnote 12 More recently, research has started to pay more attention to the links between squatting and migration. Migrants who travelled from rural areas to cities in developing countries, or from former colonies to western Europe, often squatted plots of land or buildings to acquire accommodation.Footnote 13 Pierpaolo Mudu and Sutapa Chattopadhyay have made a first inventory of the contemporary experiences of squatting refugees and sans papiers.Footnote 14 In research on squatter migrants and sans papiers, in cities such as Amsterdam, Calais and Hamburg, press reception and media framing of squatter conflicts has become a prominent theme.Footnote 15 The current article is part of these research developments, but focuses on a group of migrants with passports who squatted in a mid-sized city during the 1990s. It thus focuses on a different type of migrant squatter in a different setting, which has not yet received scholarly attention.

The term ‘squatting’ evokes images of militant youths in leather jackets who confront the police in spectacular street battles. This image not only influences popular descriptions of, and debates on, squatting, but also research, which has traditionally focused on militant squatters in metropolitan settings. Nazima Kadir has argued that this image is exclusive and distorted; in reality, the squatter population was much more diverse. By focusing on militant and metropolitan squatters as the ‘real’ squatters, other squatting people such as women and migrants are overlooked. Kadir thus calls for a more inclusive research method, which highlights the squatters’ diversity.Footnote 16 This article builds on this notion and argues that English-speaking squatters formed an integral part of the Leiden squatter population of the 1990s, comprising hundreds of youths, and played a significant role in conflicts over urban development in the city. Although they were very visible at the time, they have left few traces in the city landscape or marks on the city's collective memory. The history of these squatters, then, is also a history at risk of being forgotten. Based on a systematic analysis of local mainstream and activist media, as well as interviews, this article aims to reconstruct their position and experiences in Leiden, as well as their role in squatter conflicts.

Because most of the English-speaking squatters only lived temporarily in Leiden and organized through informal networks, they have produced little traditional archival source material. This article therefore is based mainly on systematic analysis of local newspaper reports, complemented with six oral history interviews. The abovementioned case of the Haagweg shows that local media reporting on non-Dutch squatters was not neutral. Rather, the local media functioned as a stage where various views on their actions and experiences were exchanged. Proprietors, neighbours, aldermen and the police all sought contact with the media when squatter conflicts emerged, and tried to gain support for their position. Journalists themselves also processed their own opinions and interpretations in their media accounts. The squatters were very aware of the ways in which they were framed and made efforts to counter bad press. This article, then, reconstructs the struggle for the image of foreign squatters in Leiden's local media during the 1990s. In doing so, the goal is not to mirror the mediatic images of squatter conflicts to what ‘really’ happened, but to reconstruct which groups attempted to influence the squatters’ framing, and in what way. By reconstructing the struggle for the image of these squatters, we can gain a better understanding of the composition of the Leiden squatter population, and the responses that their presence and activities evoked in the city. Such research also broadens our understanding of the city, because the English-speaking youths formed an integral part of the city's population and were involved in a myriad of social, cultural and political developments, as seasonal labourers, as subcultural actors or as squatters.

Local news media, framing and image making

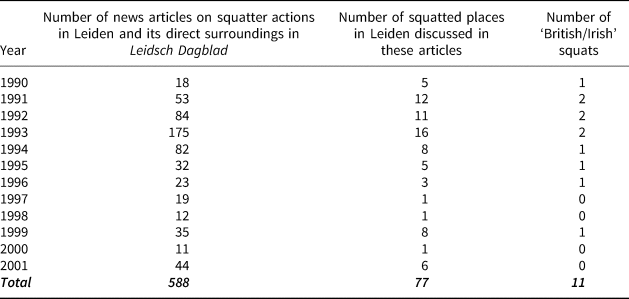

To analyse the ways in which British and Irish squatters in Leiden were portrayed, and in order to reconstruct the struggle for their image, two local publications have been researched systematically: the mainstream daily newspaper Leidsch Dagblad and the activist monthly De Peueraar.Footnote 17 The relevance of such research lies in the fact that while media reporting, image making and decision making are not the same, they are nevertheless closely related.Footnote 18 Leidsch Dagblad was the only local daily in the region and in the mid-1990s had a print-run of about 40,000.Footnote 19 For Leidsch Dagblad journalists, the squatters constituted only one voice in the case of local housing conflicts, next to neighbours, proprietors and local authorities, while their own opinions also influenced their reporting. Even so, the squatters were not completely powerless in the struggle over their image; they could produce their own media, organize actions to generate media attention, give interviews or respond to negative news reporting through letter writing. The 1990s editions of Leidsch Dagblad are completely digitized.Footnote 20 A word search using the terms ‘kraken’, ‘krakers’, ‘gekraakt’ (squatting, squatters, squatted) yielded 588 news articles in Leidsch Dagblad, of which 77 discussed the presence and actions of British and Irish squatters (Table 1). De Peueraar was a local activist monthly during the 1990s with a print-run of about 250, and is now completely digitized.Footnote 21 But even though it was a very small magazine, it was nevertheless an important part of the Leiden activist infrastructure, as the magazine was distributed among Leiden squats and social centres, and the editorial offices functioned as a local knowledge centre for Leiden activists. The editors were sympathetic to the squatters’ actions and gave them space to let their voice be heard. The editors also regularly responded to negative news reports in Leidsch Dagblad. In fact, dissatisfaction about the latter was an important reason for launching the monthly. The 52 editions of De Peueraar were systematically researched for reports on either the addresses or British and Irish squatters.

Table 1. An overview of the number of news articles in Leidsch Dagblad on (British and Irish) squatters in Leiden

Sources: This data collection was compiled from a database of digitized editions of Leidsch Dagblad, which can be accessed through ‘Historische kranten, erfgoed Leiden en omstreken’, leiden.courant.nu. A digital map of all Leiden squats can be accessed through: https://maps.squat.net/en/cities/leiden/squats.

The newspaper reports were analysed by using a framing analysis. William A. Gamson and Gadi Wolfsfeld define a frame as a ‘central organizing idea, suggesting what is at issue’.Footnote 22 When a situation is ‘framed’, certain facts are highlighted, connected to each other and together imbued with a specific meaning.Footnote 23 Squatters, for example, point to the co-existence of housing shortage and vacancies, and propose to solve the first issue by taking control over the latter. The present research analyses how different frames of foreign squatters were communicated, counterposed and interacted. In analysing the newspaper reports, we have asked who gets a voice (squatters, local residents, estate owners, local authorities), and in what way those who speak are presented (as trustworthy or not, as sympathetic or not), and if they are assigned certain qualities or characteristics (when squatters are cited, for example, their appearance, dress and hairdo is often described, which does not happen when local residents or authorities are cited). Based on this analysis, we argue that the struggle for the image of the English-speaking squatter mainly revolved around: (1) their willingness and ability to renovate houses and revive neighbourhoods, and (2) the character and frequency of raves and their supposed threat to public order.

Six interviews with former squatters from Leiden and abroad have functioned to provide further detail and complement our analysis. Interview partners were found through contacts with Doorbraak (Breakthrough), the successor organization of the one that published De Peueraar, contacts with the local social centre Vrijplaats Leiden, and by contacting local industries and cafés frequented by English-speaking youths. The interviews took the form of semi-structured qualitative interviews, in which we asked respondents to incorporate their squatter experiences into their own biographies. In all interviews, we asked respondents to reflect on their experiences as, or with, the foreign squatters, image making and the role of media in local squatter conflicts.Footnote 24

The ‘problem’ of the British and Irish squatters in Leiden

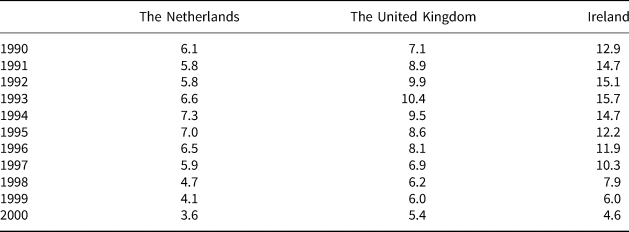

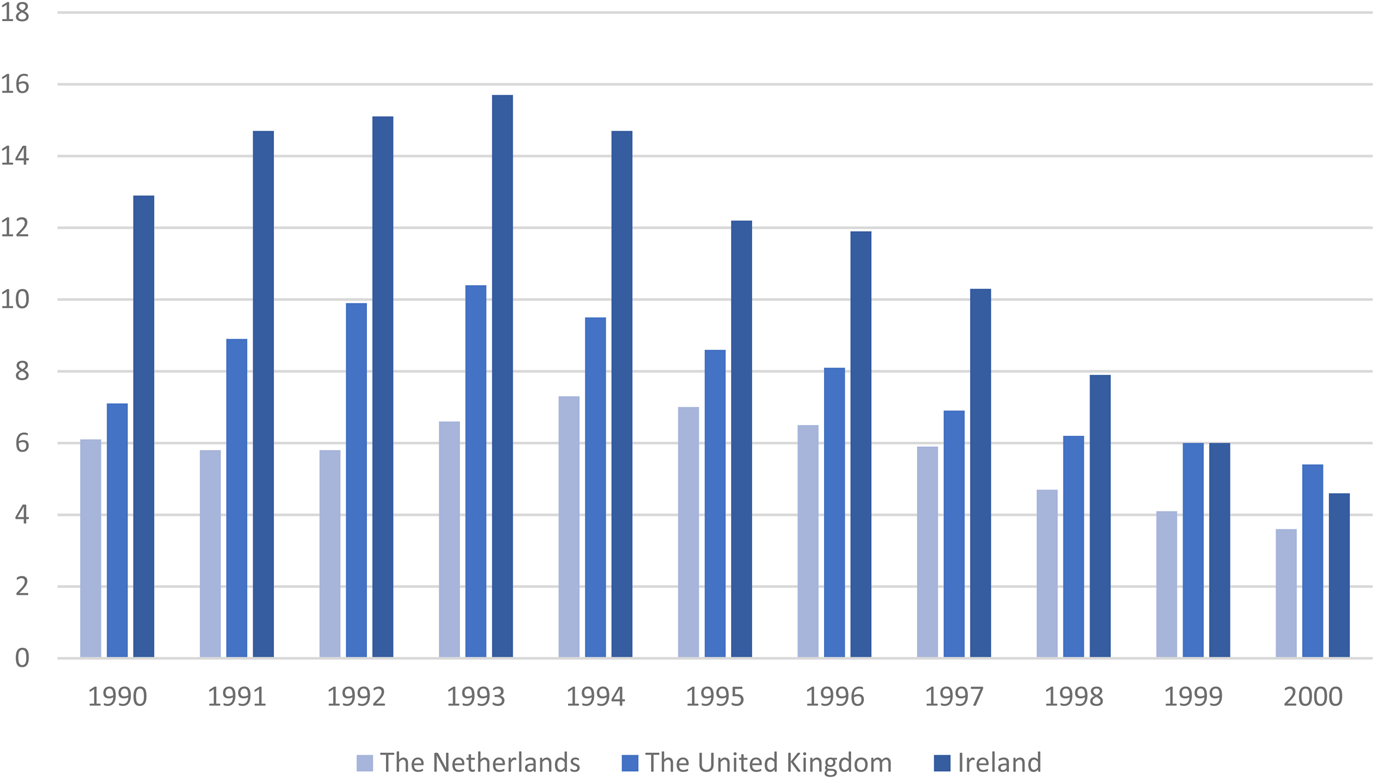

During the 1980s, deindustrialization and economic restructuring led to high levels of (youth) unemployment in large parts of the UK and the Irish Republic. A comparison of data from the Dutch Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek, the UK Office for National Statistics and the Irish Central Statistics Office shows significantly higher unemployment rates in the UK and the Irish Republic during the early 1990s (Table 2 and Figure 1). In the same period, the Dutch floral industry struggled to attract adequate numbers of (seasonal) labourers. Unemployed Dutch youths and other unemployed members of the working population often declined to work in the industry, instead favouring (low) unemployment benefits, and citing low salaries and the physically demanding labour as the main reasons. Dutch government programmes directed at reintegrating unemployed people into the labour market by making them work in the floral industry faltered due to the inability and/or unwillingness of unemployed to keep up with the working rhythms of the industry, and the strong preference of employers for seasonal labourers from the UK and Ireland.Footnote 25

Table 2. Unemployment rates in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Ireland during the years 1990–2000

Sources: Based on data from the Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek, the Office for National Statistics and the Central Statistics Office. ‘Arbeidsdeelname, vanaf 1969’, https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83752NED/table?ts=1597137979428; ‘Unemployment rate (aged 16 and over, seasonally adjusted)’, www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/mgsx/lms (accessed 16 Aug. 2020), ‘Unemployment rate 1985–2016’, www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-sdii/sustainabledevelopmentindicatorsireland2017/soc/ (accessed 4 Mar. 2021).

Figure 1. Unemployment rates in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Ireland during the years 1990–2000.

Sources: Based on data from the Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek, the Office for National Statistics and the Central Statistics Office. ‘Arbeidsdeelname, vanaf 1969’, https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/nl/dataset/83752NED/table?ts=1597137979428; ‘Unemployment rate (aged 16 and over, seasonally adjusted)’, www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/mgsx/lms (accessed 16 Aug. 2020), ‘Unemployment rate 1985–2016’, www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-sdii/sustainabledevelopmentindicatorsireland2017/soc/ (accessed 4 Mar. 2021).

By placing advertisements in British and Irish newspapers, employers from the Bollenstreek (‘bulb region’) reached out to young adults. Dozens of them replied and came to the Netherlands, as did smaller numbers of migrants from Spain and Italy. Since their host countries were part of the European (Economic) Community, workers from the UK, Ireland, Spain and Italy did not need work permits to work in the Netherlands.Footnote 26 In the early 1990s, the group of seasonal labourers from the British Isles grew into several hundreds. Most of them worked in the floral industry, but others found work in the construction sector or in food processing.

Local observers were quick to remark that these young people did not come to Leiden only in order to find work. Looking back, Pieter van der Geest, a café owner in Noordwijkerhout that amassed a large British and Irish clientele during the 1990s, emphasizes the dire economic prospects that drove the youths to come to Leiden: ‘They really came from bitter poverty…And when they came here, there was work and a good system of social insurances.’Footnote 27 Leidsch Dagblad dubbed the youths a mix of ‘economic refugees’ and ‘new age travellers’.Footnote 28 According to the newspaper, many of the youths also came to the Netherlands to enjoy its more tolerant drug policy and more generally the greater tolerance for alternative lifestyles and subcultures such as the squatter scene. According to De Peueraar, the young labour migrants were driven by various motivations: ‘Here they can at least make some money. In Ireland and England that is almost completely impossible. The more tolerant drugs policy also suits a lot of people.’Footnote 29

Although British and Irish working youths did not need a work permit, most landlords and estate agents refused to rent out housing to people without such permits. In a newspaper interview, a British youth stated: ‘It is a Catch 22 situation, we have nowhere to go. The floral companies love to have us, but we have no place to live.’Footnote 30 In August 1993, two Leiden labour party members of the city council proposed to improve the housing situation of seasonal labourers, especially because they expected a growing ‘inflow of youths’.Footnote 31 Even so, no substantial plans were made or realized, either by the municipality or by the employers. A great number of youths thus housed themselves on official or clandestine camp sites close to their work, while others decided to squat. At that time, squatting was legal in the Netherlands if the squatters could prove that the occupied building or apartment had been left vacant for a year or longer.Footnote 32

A systematic analysis of Leidsch Dagblad reports on squatting in Leiden shows that during this decade at least 77 houses were squatted, 11 of which housed British and Irish squatters. The number of ‘British/Irish’ squats may seem low, but nevertheless a Leiden police spokesperson estimated the number of English-speaking squatters in 1993 at 350.Footnote 33 Furthermore, a significant number of the 11 squats were large properties that became focal points of intense urban conflicts. Four considerations may help to contextualize the abovementioned numbers. First of all, it is possible that the police over-estimated the presence of foreign squatters in Leiden. Secondly, ‘British/Irish’ squats often housed large numbers of people. According to the police, about 50 squatters resided in the former factory building Parmentiercomplex.Footnote 34 The Leidsch Dagblad claimed that the former offices of the Dutch Postal, Telegraph and Telephone service, the ‘PTT squat’, housed about a hundred youths, partly in caravans and campers that were stationed on the office's parking lot.Footnote 35 Thirdly, although squatter actions in the villages surrounding Leiden have been incorporated in the database, they have not been processed in the map, which focuses solely on Leiden squatting. Finally, an unknown number of foreign squatters refrained from contacting either local authorities or media.

The squatting and illegally camping youths from Britain and Ireland soon became a topic of debate in the city. Initially, that debate revolved around the question whether they had a problem or posed a problem; and who was responsible for their housing. Neighbours regularly complained about noise disturbances, drug use and littering by the squatters. The latter defended themselves by stating that the municipality and the employers refused to organize proper housing. Many of these conflicts became topics of local news reporting. Investigating the images that circulated in local media forms a first step in getting to know this group of informal residents, although the source needs to be analysed with caution. Leidsch Dagblad paid quite a bit of attention to squatters, but it was not always well informed. In many cases, squatter actions were initially only mentioned in passing and it was only later, when a conflict arose, that it became clear that the house was inhabited by British and Irish youths. When Leidsch Dagblad did know that the squatters were foreign, the latter were often described in a somewhat stereotypical fashion, as somewhat exotic but not altogether unsympathetic. Often, these descriptions were rather similar to those of Leiden/Dutch squatters. When English-speaking youths occupied an abandoned villa in Warmond, a Leidsch Dagblad journalist noted: ‘The smell of bacon and eggs enters the house from one of the rooms. A girl with rasta braids and a large sweater with holes in it stirs in a pan…About ten squatters are seated on old car seats, dressed in the same way as the girl.’Footnote 36 This type of description was rather neutral and did not deviate much from the ways in which other squatters were described.

However, when ‘British/Irish’ squats became the topic of conflicts over urban developments, various actors would try and use the media to frame the conflict in their own way and make their framing the generally accepted one. In such a situation, the identity and goals of the squatters became points of contestation, and various frames were counterposed. After a brief discussion of the potential of oral history approaches to our topic, the following section analyses these conflicts in two parts. The first part analyses conflicts over the squatters’ image that developed when they presented themselves as neighbourhood activists trying to counter dilapidation and technocratic urban renewal. Although these squatters often received initial sympathetic media attention, they were not always able to maintain momentum or gain general acceptance or support. The second part analyses the contested images of a group of squatters that made little or no effort to influence media reporting, and thus became an object rather than a subject of framing conflicts.

Who were the squatters? An oral history approach

The experiences of migrant squatters can only partly be recovered from the Leidsch Dagblad. Journalists only spoke with a small number of people from a group that was very diverse, and in writing their articles, they may have had their own agenda. Oral history interviews offer a different perspective and provide former squatters the opportunity to reflect on their experiences. As part of this research project, we interviewed both squatters and people with whom they interacted closely, such as friends and colleagues. It was difficult to find British or Irish squatters who had stayed in Leiden during the 1990s and this section therefore serves merely as a glimpse into the squatters’ own experiences.

‘You could go out in the weekend and you wouldn't hear a Dutch person’, recalls Jack, an English youth who arrived in the late 1990s and became actively involved in the city's alternative scene. It paints a picture of how significant the British and Irish presence must have been in and around Leiden during the 1990s. Noel, who left Ireland at 19 years old, found work at a floral company and squatted in the villages around Leiden. He describes the ‘very drug and drink orientated’ lifestyle that he took part in. Noel and Jack both felt that they were thought of as strange because of their alternative way of living.

This is in part acknowledged by two former colleagues, who recall how the alternatively dressed youths remained outsiders in the otherwise rather conservative village of Noordwijk, where they worked: ‘The English and Irish were much freer than us Dutch people.’ Interestingly, the youths’ relative isolation seems to have strengthened the group's cohesion. According to Pieter van der Geest, whose bar became a hub for the foreign youths working in the bulb region, the differences between British, Irish and Scots dissolved, as they socialized and partied together. ‘At home it was unthinkable for a Catholic and a Protestant to talk to each other’, he reflects.

For most youths, their stay in Leiden lasted only a couple of months, and for some it was merely a stopover to other, more exciting and more memorable places. Work in the bulb region was often not a goal in itself, but a means to an end. The more adventurous of the youths used their wages to fund travels to countries like Thailand and India. It is part of the reason the group remains so elusive today.

Oral history research based on extensive interviews with a sizable pool of English-speaking squatters proved unfeasible and this needs to be taken into account when analysing this source. The interviews, however, do provide a first glimpse into how the squatters remember their Leiden phase, and how they are remembered. The present article, however, focuses on their media framing during the 1990s.

Urban decay versus neighbourhood activists

Squatting of houses can be an individual strategy to acquire a place to live, but it can also be part of a collective effort to regenerate a neighbourhood by combatting vacancy and dilapidation, speculation and urban decay. The discourse of squatters fighting urban decay was often heartfelt, but it could also be used strategically by squatters to legitimize occupations that served more self-serving purposes, such as party squats. Opponents of squatting often countered that squatting delayed urban renewal projects, and that instead of neighbourhood improvement squatters were responsible for noise disturbance and littering. These two frames, of squatters as answers to or causes of urban decay, were often counterposed in media reports on squatting.

Usually, the opponents of squatting received more media attention and subsequently gained more sympathy from the public. Sometimes, however, squatters managed to gain an important voice during such conflicts. This happened when local authorities clearly neglected neighbourhoods, while the squatters countered this by strong organization, inventive actions and perseverance.Footnote 37 Often in such cases, the squatters’ persistence led to polarization and more intense framing activities. This can clearly be seen in three cases where English-speaking squatters in Leiden presented themselves as neighbourhood activists. The following section will demonstrate how these two frames – of squatters as neighbourhood activists or as the cause of urban decay – were counterposed and competed with each other. The more effective the squatters were in their media strategies, the more intense the debates became.

The first conflict unfolded in the early 1990s at the end of the Morsweg, just outside the city centre, where the municipality wanted to demolish a row of houses in order to build a business park. Between 1990 and 1994, various groups of squatters occupied a number of houses, but they did not manage to form a tight-knit collective with a clear voice in the media, which led to lukewarm attention from the media. During the process of dispossessing the houses, which took years, the municipality neglected the area, which as a result became dilapidated. The first group of squatters told Leidsch Dagblad in June 1991 that they wanted to smarten up the neighbourhood: ‘We have improved the road and want the houses to remain. We are going to establish an association to renovate the houses.’Footnote 38 Together with the last official resident of the street, they used the frame of neighbourhood activists fighting against neglect and dilapidation. But already in October 1991, Leidsch Dagblad quoted a police spokesman, who stated that the foreign and Dutch squatters at the Morsweg did not get along.Footnote 39 The former were assumed mainly to use the houses as temporary residences, while the latter supposedly had a more long-term vision for the houses. This made it difficult for the squatter group as a whole to claim the status of neighbourhood activists.

Additionally, the municipality's neglect of the neighbourhood made it extra difficult for the squatters to counter urban decay. According to the last legal resident, not even the garbage was collected anymore, while the squatters complained that the police did not take action against a drug dealer who had set up shop in one of the dispossessed and vacant houses.Footnote 40 Leidsch Dagblad did not confront the municipality with these accusations, and only once asked the municipality to give a reaction about the situation in the Morsweg. In June 1994, a conflict between the drug dealer and a group of men caused a fire that spread to a neighbouring (squatted) house.Footnote 41 The squatters’ lawyer subsequently asked in Leidsch Dagblad why the police had not intervened earlier, and why the fire brigades had not helped the squatters to make their houses fireproof.

The neglect of the area by the municipality and the lack of a consistent media policy among the squatters left them vulnerable to being blamed for the bad state of the neighbourhood. The advertisement weekly Het op Zondag stated that the English-speaking squatters at the Morsweg were to blame for the neighbourhood's deterioration, since they were only interested in drugs and house parties. Leiden's Kraakspreekuur (Advisory Service for Squatters) protested this claim with an open letter to the weekly, dubbing the accusations ‘exaggerated and untrue’.Footnote 42 However, by this time, residents from neighbouring streets also had started to blame foreign squatters for the problems at the Morsweg.Footnote 43 In 1995, the houses were demolished by the municipality. Although the different groups of squatters had tried to work together to improve the neighbourhood and preserve the houses, they had not received much sympathetic coverage from the local media. It seems that the municipality's neglect of the problems in the street resulted in a dynamic in which the last resident, the squatters and the dealer were played out against each other. Because of the squatters’ lack of unity and organization, they were unable to counter negative news framing effectively.

In the second case, the municipality was forced to intensify its involvement as it had to respond to more effective media activities from the squatters. In 1992, a group of British and Irish youths squatted the former offices of the Dutch Postal, Telegraph and Telephone (PTT) service at the Koningstraat. Within a year, about a hundred youths lived in and around the PTT squat, partly in campers that were parked in front of it.Footnote 44 At first, Leidsch Dagblad only mentioned the occupation in a brief report. However, in July 1993, the neighbourhood committee voiced complaints to the municipality: ‘The squatters are shouting in the middle of the night, ride around in shopping carts, and play their music at maximum volume.’Footnote 45 When questioned by Leidsch Dagblad, however, the police stated that they had not received any complaints. The squatters responded with an interview in Leidsch Dagblad, in which they introduced themselves. They stated that they cared for the neighbourhood and had even bought their own waste containers. According to the squatters, they were being judged on their appearance, rather than their actions: ‘Whenever we arrive somewhere, people start to gossip about us.’Footnote 46 The squatters may not have made a particularly good impression in the newspaper, but at least they were asked for their side of the story.

After this episode, the squatters’ image changed to a more positive one, albeit for a short amount of time. Responding to the obvious tensions in the neighbourhood, two labour party members of the city council organized a meeting between the squatters and their neighbours in August 1993.Footnote 47 According to the council members and the neighbours, the meeting went ‘better than expected’.Footnote 48 The squatters promised that they would take the complaints of their neighbours into account, and the neighbourhood committee printed flyers, which stated: ‘Make friends in the neighbourhood’. The committee chairman, Bram de Pater, described to Leidsch Dagblad how the situation had improved: ‘I was standing next to that fence, and three English people walked by and called: “Hey, what's your name”. So, I yelled: “Bram”. They shouted back: “Nice to meet you Bram”. Nice huh?’Footnote 49 Just two weeks later, the building was sold. By then, the relationship between the squatters and the neighbourhood had again soured. De Pater stated in response to the news of the building's eviction: ‘The neighbourhood is bloody happy.’Footnote 50

The struggle over the identity and lifestyles of the squatters continued, even after the squatters had left the property. Leidsch Dagblad reported that the new owners of the building ‘could barely suppress their disgust’ upon entering the abandoned building: ‘They [the squatters] used that bucket as a toilet. They destroyed everything and left their mess everywhere. Food is still left over there. And there are also needles lying around.’Footnote 51 Again, Leiden's Kraakspreekuur replied with a letter, in which they explained that the needles had been used by a squatter with diabetes, and stated that ‘it would be illogical to leave a building in a spotless condition if it is going to be torn down anyway’.Footnote 52 This second case shows on the one hand that Koningstraat squatters took offence at negative news reporting, and responded to it, but also that squatters were not always committed enough to counter bad press effectively. One interview and a letter to the newspaper would not suffice to challenge negative news framing.

Two reasons may explain the difficulties that British and Irish squatters struggled with when developing a consistent and effective media politics. To begin with, there was the number and the ever-changing composition of the seasonal labourers that squatted, which made it difficult to form stable groups committed to collective action. The fluidity of the group, and their relationship towards squatted houses, was often informed by their short-term stay in Leiden as seasonal labourers. According to a former editor of De Peueraar, Piet, the squatters at the Morsweg and PTT squats were ‘often less organized’: ‘At the Morsweg, where many English-speaking squatters lived, there was someone who took care of practical things like water and such, but I do not believe they had assigned someone to speak to the press.’Footnote 53 While some squatter and direct-action groups in Leiden, such as the Eurodusnie collective, developed a well-organized media policy – consisting of media scripts, appointing spokespersons and writing press releases – groups of foreign squatters often lacked the organization to co-ordinate such efforts.Footnote 54 Next to organization, language proficiency was also an important factor. English-speaking squatters often approached native Dutch-speakers to talk to the press or to authorities, local squatter Margit remembers.Footnote 55 Finally, the connections of squatters to the neighbourhood and the sincerity of their efforts to revive neighbourhoods may also have played a role. When these were well developed, foreign squatters became more vocal and more prominent. When this happened, however, the opposition also hardened and they did not do enough to counter the image of them produced by the journalist and neighbours. This was the case with the Parmentiercomplex.

In the case of the Parmentiercomplex, squatters worked together with neighbourhood activists to preserve the old factory building and the houses around it, which resulted in a relatively well-organized media strategy. The Parmentiercomplex was built in 1893 as a steam spinning mill, and repurposed in 1941 into a hardware store, until it was closed in 1989. When it was first squatted in February 1991, neighbours instantly supported the squatters and their protest against the demolition of the monumental building in favour of a disco and luxury apartments. In an interview with Leidsch Dagblad, the squatters told the newspaper that they planned to turn the building into apartments, a community centre, a bar and a skateboard track. They also protested housing shortage and stated: ‘We will not make room for a disco as long as we do not have a roof above our head.’Footnote 56 Residents protesting the demolition and disco in their street were jubilant. The chair of their action committee told Leidsch Dagblad: ‘I am very happy that the Parmentiercomplex has been squatted. The squatters are lovely kids. And they protect the building against vandals and thieves that have already ransacked the place.’Footnote 57

Alderman Van Rij, responsible for urban development in Leiden, however, wanted the squatters out as soon as possible and started a negative media campaign. Van Rij described the squatters as antisocial and unhygienic, and stated that the building had no running water: ‘Squatters are simply defecating on the local square.’Footnote 58 Van Rij ordered the municipal health service to investigate the supposed threat that the squatters posed to local hygiene and told the city council that the squatters were to be evicted for that same reason. De Peueraar was furious and spoke of ‘a non-existing problem’ invented by the alderman in order to evict the squatters.Footnote 59 Leidsch Dagblad followed up on the story and interviewed the inspector of the municipal health service, who voiced his irritation over being ‘used’ to legitimize an eviction. In the end, his report was one page long, and concluded that the squatters were ‘absolutely harmless’.Footnote 60

Unwilling to accept defeat, Van Rij now stated that the building posed a fire hazard. The municipality told the owner either to evacuate the building or to make it fireproof, which Leidsch Dagblad found strange since the owner was already in the process of getting a court order to evict the squatters.Footnote 61 A columnist of the Leidsch Dagblad concluded that Van Rij was a ‘concrete junky’, who employed ‘cunning schemes’ to have the Parmentiercomplex evicted.Footnote 62 Van Rij tried to use Leidsch Dagblad to frame the squatters negatively, but for various reasons, the newspaper did not accept his claims without reservations. The fact that the squatters enjoyed support in the neighbourhood and played a central role in an important urban development conflict meant that the municipality could not simply ignore them, as they had done with the squatters in the Morsweg. Ironically, the more effective media strategy of the squatters resulted in ever more aggressive counter measures by their opponents, in this instance the alderman.

Even so, the squatters did not manage to sustain their protest because of the changing composition of the group and a resulting change in mentality. In December 1992, the composition of the squatter group at the Parmentiercomplex had changed and a new group of squatters told Leidsch Dagblad: ‘We are not ideological or anarchist squatters. We are much too old for that. We only want a roof above our head.’Footnote 63 De Peueraar subsequently reported that conflicts had broken out between different groups of squatters, and that the in-house squatter bar had moved to another location because of it.Footnote 64 From this point onwards, the complex acquired a reputation for hosting large house parties and lost its connections with the neighbourhood. Eventually, alderman Van Rij filed a lawsuit against the squatters, after which a judge decided that the squatters had to leave before 1 April 1993. The police evicted the complex on 1 April, after which the building caught fire and burned down on 4 April. In the case of the Parmentiercomplex, squatters and neighbourhood activists had managed for some time to successfully counter negative news framing by the local authorities. Still, it was not the media or public opinion that ultimately decided the fate of the complex, but the court. By that time, however, the squatter group was no longer part of local protests against urban renewal and a disco. The group had changed in part because, as seasonal labourers, foreign youths came and went, because their preference for specific squats in the city changed and finally because of tensions among the squatters. Under such conditions, it was very hard to keep up a consistent campaign against urban renewal projects as well as an accompanying media strategy.

In all three cases, British and Irish squatters lived in houses and properties that were in a very poor condition. Often, these were places that Leiden squatters did not even consider squatting. Sometimes, they were driven by other motivations than local squatters. As seasonal labourers, they viewed squatted places as temporary dwellings, whereas long-term preservation and legalization of the buildings required tenacity, strong organization and a long-term vision. In this context, it is ironic that the instant measures that these squatters took to improve the neighbourhood's quality of living, such as buying waste containers, were seen by the local residents as signs of urban decay.

To conclude, the British and Irish squatters were seldom successful in presenting themselves successfully as combaters of urban decay and in gaining general acceptance of their vision on urban issues. They got opportunities to talk to the local newspaper Leidsch Dagblad, but their narratives were often over-ruled by those of neighbours, owners and local authorities. The municipality responded differently to their actions. At times, they would ignore the squatters altogether (Morsweg), while at other times they would try to mediate between squatters and neighbours (PTT squat), or paint them in a negative light (Parmentiercomplex). Either way, the squatters’ demands were never seriously considered or met by the municipality, which in part explains why the British and Irish have been largely forgotten as part of the Leiden squatting population and as part of the city's population as a whole. None of their attempts to maintain or preserve properties were successful. Political relations and legal opportunities explain this to a large extent, and it remains unclear how much the squatters could have achieved had they possessed a strong organization and effective media strategy. Nonetheless, even from Leiden there are known cases, such as Haagweg 4, where changing public opinion could cause favourable political decision making. The squatters and their allies did try to influence news framing, by giving interviews, writing letters, taking action and working together with neighbours. In the end, however, these media interventions were too unstructured and haphazard to be effective. Ineffective media strategies were among other issues a consequence of the squatter population's unstable composition and their isolation from Leiden squatters and the city population in general – which was in part caused by language issues.

An invisible network

The aforementioned squatter actions can be viewed as attempts both to acquire alternative housing and to defend the interests of the neighbourhood. In most cases of British and Irish youths squatting houses, however, acquiring spaces to facilitate alternative forms of life was the main goal. Among them was a small group of politically active squatters, but also a large group of alternative youths, who soon formed a lively rave scene in Leiden. This group had little interest in the media, but this did not prevent the media from writing about them. Various cases show that news reporting and framing would develop a dynamic of its own when squatters refrained from countering bad press.

Raves and house parties raised concerns among authorities and local residents, first of all about noise disturbance, but also about groups of uncontrollable youths roaming the city. A turning point in the image of alternative raving youths was the Castlemorton festival in Britain in May 1992. That month, 40,000 youths came together ‘out of nowhere’, with vans and RVs, for a week-long house festival. According to filmmaker Brian Welsh, the festival shocked British authorities to their core: ‘The fact that tens of thousands of young people found each other, without the police sensing any danger – and that in a time before the internet, before mobile phones – that was experienced as an immense loss of control.’Footnote 65 Conservative British media responded by publishing spectacular stories about the festival, while the government took a series of measures to curtail the scene's freedom of movement; most notably the 1994 Criminal Justice Act which provided police ‘the power to shut down events featuring music that's “characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”’.Footnote 66

In a study of West German squatters during the 1980s, Jake Smith used the term ‘network sublime’ to describe the concept of ‘awe-inspiring social networks running beneath the surface of everyday life’. Above all, the term refers to the fascination and fear that is evoked among outsiders when groups come together ‘out of the blue’, transgress social norms, violate rules and challenge authorities.Footnote 67 British and Irish ravers during the 1990s evoked similar fears; initially in the UK and the Irish Republic, but later also, albeit on a smaller scale, in Leiden. Such fears were fuelled by radical thinkers such as Hakim Bey, who embraced the youths’ new ways of mobilizing as a means to undermine the capitalist order. In his pamphlet, Temporary Autonomous Zone, Bey proposed: ‘Let us study invisibility, webworking, psychic nomadism – and who knows what we might attain?’Footnote 68 Indeed, news reports in Leiden's local media usually focused on the uncontrollability and invisible networks of the ravers.

English-speaking squatters and local likeminded youths soon managed to appropriate a number of stable and more fleeting spaces to organize raves and house parties. According to Margit, a local squatter in the 1990s, these parties were characterized by an exuberant atmosphere: ‘It was fantastic. Of course, we also caused some nuisance or noise complaints now and again. One time, Spiral Tribe, a British sound system, came to the PTT squat and gave an impromptu techno party that not all the residents were happy with.’ A house party at the squatted Groencomplex at the Pieterskerk-Choorsteeg lasted for 48 hours, according to Margit. On Sunday morning, the police came by the door to ask if the volume could be lowered, so as not to disturb the neighbouring church service.

According to the police and Leidsch Dagblad, hundreds of people would attend these parties.Footnote 69 After British and Irish youths had squatted the NEM hangar in Leiden in June 1996, neighbours complained to the police about the noise. Arriving at the scene, the police were alarmed to see that ‘there were six hundred people present’.Footnote 70 Next to attracting large crowds, large house parties in dilapidated buildings could lead to fire hazards. In the case of the Groencomplex, which had been squatted in January 1992, local residents, the fire brigade and members of the city council expressed concerns about the safety of visitors of house parties at the complex.Footnote 71 The sense of loss of control was further increased by the fact that the police were unable to intervene. In the case of the Groencomplex, the squatters had a legal right to residence until the owner received an eviction permit from a judge. Until that moment, a police spokesman told Leidsch Dagblad, ‘it is a private party. We cannot forbid it.’Footnote 72 In other cases, immediate police intervention was simply not an option. During the abovementioned house party at the NEM hangar, the police felt incapable of controlling or dispersing the crowd of six hundred: ‘We were afraid that the situation would escalate if we confiscated their installation.’ After deliberating with the organizers, the party could be continued but the volume had to be lowered.Footnote 73

The police repeatedly expressed concerns about a ‘secret network’, which was behind the weekly raves and which the police could not identify. An officer told Leidsch Dagblad: ‘The organization is very professional. I think these people do it every week, but in a different place each time. And they do it so silently that nobody knows anything about it. But within squatters’ circles it is apparently passed on well.’Footnote 74 The notion of such a secret network was further reinforced by the fact that foreign squatters had little contact with the press and did nothing to dispel such ideas. It placed the police, local residents and the fire brigade in a position where they could paint a negative picture of the supposed ‘network sublime’, without being countered in any way. Possible positive aspects of the network, or of the actions of these squatters, cannot be found in the Leidsch Dagblad. It is striking that squatters rarely contradicted criticisms or were given space to refute accusations made at their address.

Only in one instance did a conflict between raver squatters and the property's owner develop, leading to conflicts over the squatters’ image. Two groups had taken up residence in the squatted Groencomplex, one consisting mainly of Dutch- and another consisting mainly of English-speaking squatters. Once the owner had received an eviction permit, both groups agreed to leave the property, but asked for time to find replacement housing.Footnote 75 The owner then offered both groups 9,000 guilders each in exchange for a quick evacuation of the building. Initially, both groups agreed.Footnote 76 On the day of the eviction, however, the second group of squatters demanded a higher sum. According to the owner, the group asked for 10,000 guilders per squatter. Initially, the owner told Leidsch Dagblad: ‘We cannot give in to such demands. Those Englishmen are blackmailing us. Their demands are disproportionate.’Footnote 77 The following day, however, it turned out that the owner had given the English-speaking squatters 18,000 guilders on top of the original 9,000 guilders they were promised.Footnote 78

The squatters informed Leidsch Dagblad that they would not comment on the incident. The owner, however, did respond and said he felt ‘extorted’. ‘Feeling embarrassed’ and ‘whilst shaking his head’, he told the newspaper: ‘This has set a serious precedent. Squatting can now become a very lucrative business.’ He believed that the foreign squatters had behaved ‘outrageously’.Footnote 79 Leidsch Dagblad published over a dozen articles about the conflict and gave ample space to the owner, local residents and authorities, who each expressed their indignation at the course of events. A police spokesman responded ‘with amazement’, and warned, ‘paying squatters can attract new groups’.Footnote 80 The squatters did not engage in the conversation, leaving the accusations uncontested.

Contrary to Leidsch Dagblad, De Peueraar did not distinguish between Dutch and non-Dutch squatters, but spoke about the Langebrug and Pieterskerk-Choorsteeg squatters, since one group lived in the part of the complex that looked out on the Langebrug street while the second lived in the part that looked out on the Pieterskerk-Choorsteeg street. Still, it also bothered the editors of the activist monthly that the squatters had accepted the money: ‘The squatting editor [of De Peueraar] rejects accepting such “get lost bonuses” by squatters…With all that money in your pocket, you still won't have a roof over your head.’ The editor stated the following about the English-speaking squatters: ‘Unfortunately, they weren't able to enjoy their money for long, because one of them took off and left with most of the money…He is probably in Thailand by now.’Footnote 81 De Peueraar, however, was especially critical of Leidsch Dagblad: ‘Apart from what the squatting editor thinks of such a commutation for ideals, the smear campaign that Leidsch Dagblad has conducted is downright ridiculous.’Footnote 82 The editor was bothered that the acceptance of money was linked to the squatters’ foreignness, and believed the news reporting carried a xenophobic undertone.

The eviction of the squatters of the Groencomplex and its aftermath was one of the few times that outright xenophobic comments were published in Leidsch Dagblad. Locals who were asked about the payout to the squatters were disgruntled and angry in response. An elderly couple dubbed the incident a ‘great scandal’. The couple insisted that they had ‘no bad feelings towards the English’, but nonetheless wondered what they were doing in Leiden and expressed their wish that ‘they would return home, quickly’. Another local told the newspaper that it would have been ‘cheaper’ to hire a group of thugs to evict the property forcefully and so ‘get rid of the squatters’.Footnote 83 While xenophobic comments like these can be found in some Leidsch Dagblad news reports, they were not the norm and seem to have been an exception rather than a rule.Footnote 84 Even in the face of these kinds of comments, the squatters refrained from responding via the media.

The fascination for the ‘network sublime’ and the squatters’ attitude resulted in a situation where Leidsch Dagblad paid quite a bit of attention to the squatters, even though they were not at all interested in courting the media. Unlike the more politically driven squatters, this group withdrew from the public debate and focused on its own subculture. As a result, British and Irish squatters were mainly spoken of in news articles rather than speaking for themselves, and their presence in Leiden was framed solely by other actors such as neighbours and landlords. This led to the squatters being portrayed generally negatively in the local press. Still, although there were obvious differences between the political and subcultural squatters, as well as moments when both groups clashed, the boundaries between both groups were rather fluid, and there were many who easily moved between both scenes.

Conclusion

British and Irish squatters formed a very visible group in Leiden during the 1990s. Due to their position as (temporary) migrant workers, they occupied a special place within the city's population, which was further strengthened by their alternative way of life. Although they resided legally in the Netherlands, they had little to no access to the regular housing market. Squatting offered a way to acquire temporary shelter for as long as they stayed in the Netherlands. As a result, however, they got involved in several conflicts over urban development projects. The squatters responded to negative news framing and presented the press with their own story. However, they were rarely successful in becoming a significant voice in such conflicts.

In research on the relations between migration, squatting and media framing, these squatters occupy a position of their own. Like many other migrants, they performed temporary and unskilled labour, had a low income and had to fend for themselves on the housing market. At the same time, however, they legally resided in the Netherlands and had a western European background. Their position differs fundamentally from that of squatting sans papiers in today's Amsterdam, Calais or Paris. English-speaking squatters were singled out in local media outlets and described with some suspicion, but outright xenophobia played only a minor role in the reporting on and discussions about their presence in Leiden. As a result, the case of the British and Irish squatters in Leiden not only highlights the diversity of Leiden's squatter population in the 1990s, but also the different reactions of the city to different migrant groups.

News media have long been an important source of research into squatting and social movements more generally. Initially, newspaper reports were used as a source of objective information that could be used for quantitative analyses. Researchers from Charles Tilly to Sidney Tarrow and Hanspeter Kriesi were able to map protest waves using these sources.Footnote 85 The objectivity of newspaper reports has always been contested, but for some time now it has been debated to what extent, and under what conditions, newspapers can be used for quantitative research. As interest in protest actions declines, they also receive less attention in newspapers, which can have a significant impact on the reliability of large datasets.Footnote 86 This is even more true of movements that organize locally; Leiden squatter actions have rarely received attention in national newspapers, in contrast to squatting in Amsterdam. Waves of protest observed by researchers may at times reflect the attention of the media more than they reflect the efforts of protesters. Since the 1980s, newspaper reports have mainly been used as a means to investigate media images, especially through framing analyses. In the case of squatting, however, this approach brings with it specific challenges.

Local squatter movements usually form scenes in which radical politics and underground subculture intertwine. This certainly applied to British and Irish squatters. But while activists actively seek out media, subcultural actors tend to shy away from the media. And while activists reach out to authorities and local residents, often via the media, subcultures usually remain quiet and are talked about. This duality also informed newspaper reporting in the 1990s, which makes it difficult to define British and Irish squats as pure political actions and to analyse them through the conceptual framework of social movement studies. A framing analysis, for example does not map the actual experiences of the squatters, nor the battle for their image, but rather the commitment of some of them to influence their image. However, while newspaper reports provide central but incomplete data on the number of squats and the experiences of squatters in Leiden, they reveal in detail how important urban actors such journalists, authorities and neighbours viewed them and interpreted their actions. By doing so, they turned the newspaper into an arena where differing frames, i.e. interpretations, of squatter conflicts were presented, counterposed and interacted with each other.

Our research shows that British and Irish squatters were often written about in the local press, and that they regularly responded to the ways in which they were described and viewed. It further shows that the squatting youths did not always have the intention or ability to develop a consistent and effective media strategy. This had a direct impact on their bargaining power as squatters. Obviously, news reporting, image making and decision making are not the same, but they are closely linked. When activists want to influence political decision making, they usually do so by directly addressing authorities through mediagenic actions. If they appear to gain broad support as a result, this will put pressure on the authorities. Squatters are usually aware of this and have developed an extensive repertoire of media interventions since the 1960s. While none of the British and Irish squats were legalized, the group of Leiden artists who squatted Haagweg 4 managed to turn the plea in their favour. Among other causes, the positive media image that the artists managed to create played a role in their success.

Acknowledgements

An early version of this article was presented at the 2019 Urban History Group Conference ‘Voices of the City’ in Belfast. Parts of the research were published in Dutch in Tijdschrift voor Sociaal-Economische Geschiedenis, 17 (2020). The authors thank Tim Verlaan, Jasper van der Steen and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism on an earlier version of the text.