1 Introduction

Access to civil-law institutions has been a traditionally important area of socio-legal research, whereas access to administrative justice still constitutes an underresearched field. While there is a multi-faceted body of literature on the access to civil justice, access to administrative justice seems to be uncharted territory within the different approaches to access to justice (Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008) and more generally the literature on legal mobilisation (Albiston et al., Reference Albiston, Edelman and Milligan2014; McCann, Reference McCann, Caldeira, Kelemem and Whittington2008). Few attempts have been made to carry insights from the literature on access to civil justice over to access to administrative justice (Adler, Reference Adler2003; Halliday and Scott, Reference Halliday, Scott, Cane and Kritzer2010). Overall, we know little about the extent to which our knowledge in the field of access to civil justice may help us to understand legal mobilisation processes that occur when individuals or social groups face the state. We therefore also know relatively little about who does or does not engage in contact or litigation with administrative bodies and for what reasons; inequalities in access to administrative justice and its determinants are in particular a blind spot.

While the concept of access to justice has several dimensions, it generally revolves around the idea of ensuring equal and effective access to independent dispute-resolution mechanisms for individuals who have experienced some kind of damage, regardless of the socio-economic status, gender or ethnic background attributed to them. In the field of administrative law, public-sector ombuds institutions are an alternative pathway to resolve disputes without appealing to a court. Traditionally, one of their aims is to offer low-threshold access to administrative justice. Public-sector ombuds institutions have existed in most countries since the 1950s, but they have become increasingly popular over recent decades (Carl, Reference Carl, Hertogh and Kirkham2018; Koo and Ramirez, Reference Koo and Ramirez2009). This is in part due to the popularity of the alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms that the ombuds is often associated with (Creutzfeld, Reference Creutzfeld2018; Remac, Reference Remac, Dragos and Neamtu2014). Today, the ombuds is an important and permanent feature of legal systems in most parts of the worldFootnote 1 and many countries have both public-sector and private-sector ombuds.

The public-sector ombuds, which we will focus on in this paper, is an interesting hybrid in the justice system. It is a body that provides ADR outside of the national court system and thus represents an additional path to accessing justice (Creutzfeldt and Bradford, Reference Creutzfeldt and Bradford2016). Public-sector ombuds can (1) inform claimants on the legal aspects of their situation; (2) receive, investigate and examine complaints; (3) advise, assist and support victims of discrimination; and (4) provide conciliation, mediation or negotiation between the parties (Carboni, Reference Carboni2014). They control the work of public administrations and can take positions in favour of citizens or report incidents to the parliament in order to provide remedies for bureaucratic abuses of power or restore citizens’ trust in government. We therefore believe that ombuds institutions are of crucial interest to the field of access-to-justice research. Nonetheless, there is still a lack of empirical research on the characteristics of ombuds users and on the institutional mechanisms impacting the profiles of these users.

If in theory the public-sector ombuds can offer easy and equal access to its services from an access-to-justice perspective, whether this is the case in practice remains to be ascertained. In studying who appeals to ombuds institutions, do we find the same inequalities in terms of class, race and gender that the access-to-civil-justice literature has observed? Socio-legal scholars who have tackled this question show that ombuds complainants typically constitute a specific population of highly educated, middle-aged, white-collared, politically interested men. Disadvantaged or vulnerable persons usually will not find such ADR bodies and procedures easily accessible or user-friendly (Creutzfeld, Reference Creutzfeld2018; for an overview, see Hubeau, Reference Hubeau, Hertogh and Kirkham2018). The consistency with which scholars reveal inequality in the access to ombuds institutions is striking but, as Creutzfeldt (Reference Creutzfeld2018) points out, at the same time, our empirical knowledge about the value of ADR approaches in relation to access to justice remains very thin. We still lack data on the users, but also on the non-users and on what can be done about non-use.

The paper follows a twofold aim: building on survey data among users of our case-study, we first study the Austrian Ombudsman Board (AOB) users’ demographic characteristics to evaluate whether the threshold for accessing the ombuds institution can effectively be said to be low, as the institution itself claims. By exploring who accesses the ombuds and who does not, we will reach conclusions on the extent to which the AOB provides equal access to administrative justice for all. In a second step, we focus on the role of ‘institutional design’ (Albiston and Sandefur, Reference Albiston and Sandefur2013) or ‘redress design’ (Le Sueur, Reference Le2012) for the access to ombuds services. Connecting to previous research, we depart from the assumption that the design of (civil) dispute-resolution institutions has a significant impact on who gets access to justice.Footnote 2 Our aim is to understand whether specific features of the institutional design of the AOB impact the sociodemographic characteristics of the population of complainants. We investigate the effects of institutional design through two outreach measures that represent key pillars of the AOB: first, regularly organised consultation days, held in all Austrian provinces, where people can file a complaint in person to an ombudsperson, and, second, a weekly TV broadcast in which current cases are discussed in the presence of an ombudsperson and the concerned complainant. The objective is to find out whether these two outreach measures effectively change the profiles of the citizens who address the national ombuds institution in such a manner as to correct the inequality in access to justice that scholars have observed for a long time. Our results show that this is the case and therefore underline the importance of design for the study of how access to administrative justice is produced.

2 The case: the AOB

The AOB (Volksanwaltschaft) was established in July 1977 as one of the supreme bodies of the republic. It monitors all authorities, administrative bodies and departments of the state, the provinces and the local government authorities across the entire federal territory.Footnote 3 The AOB consists of three members elected for a six-year term by the Austrian parliament (National Council). They are each in charge of one area of responsibility.

The AOB's activities are divided into an ex post investigative strand and a preventive strand (ex officio as well as human rights (OPCAT) investigations).Footnote 4 The AOB's key task has always been to investigate complaints from citizens and assess whether the administration is acting within the law and complies with general principles of what today would be called ‘good administration’. In this capacity, the AOB assists citizens who consider themselves to be treated unfairly by an Austrian authority. Complaints may pertain to the inactivity of the authority, a legal opinion that does not comply with the relevant laws or an act of gross negligence. Currently, the AOB has around ninety-five employees; around half of them are legal experts who handle the cases (Volksanwaltschaft, 2019). In 2018, the AOB received more than 16,000 complaints (ibid.).

The AOB has implemented two outreach measures that are key pillars of the institutional design: consultation days and a TV broadcast. Regularly held consultation days seem to be a relatively common – though not entirely widespread – feature among public ombuds institutions; however, we lack recent data on the subject. In the early 1980s, Hill (Reference Hill and Caiden1983) found that under one in three Western ombuds institutions had set up outreach measures. One decade later, Kempf and Mille (Reference Kempf and Mille1992) showed that 68 per cent of forty-eight ombuds institutions surveyed worldwide hold a consultation day. More recently, Kucsko-Stadlmayer's (Reference Kucsko-Stadlmayer2008, p. 488) formal comparison reported that in 40 per cent of all European ombuds institutions, citizens are obliged to submit their complaint in written form, which limits the institution's accessibility for individuals who struggle with administrative literacy.

In the Austrian case, the three ombudspersons hold regular consultation days in different district authorities in all the Austrian provinces (on average 230 consultation days per year – author's calculation based on analysis of annual reports). The consultation day allows citizens both to meet the ombudsperson in person and to file a complaint orally. Since, in theory, the complainant does not have to be able to read and write, the consultation day is conceived of both as a symbol and a practical measure for ensuring easy access to the institution. This ambition has been restated in almost every AOB annual report since 1977: easy, unbureaucratic, informal access to the institution is a major concern. Whereas the consultation day itself has no legal foundation, the measure has become a staple of the AOB's organisational culture.

The second specific feature is the AOB's weekly broadcast on public TV (Bürgeranwalt) in which recent cases are discussed in the presence of an ombudsperson, a claimant and sometimes representatives of the relevant authority. Ombudspersons appear in this show as staunch defenders of citizens and their rights; they present themselves as a body that finds solutions to individual problems with the bureaucracy but also deals with broader issues. The broadcast, which was introduced in 1979 (there was a hiatus between 1991 and 2002), is highly popular, attracting an average of 324,000 viewers in 2017 (a 23 per cent market share at that time slot).Footnote 5 Between 2007 and 2018, around 1,000 cases were discussed on the programme (Hadler, Reference Hadler2018). To our knowledge, the existence of this weekly TV show is unique in the field of ombuds institutions.

In this paper, we will explore how these two outreach measures – consultation days and the weekly broadcast – affect the composition of the population of complainants.

3 Methodology

This case-study is based on a mixed-methods research design consisting of a variety of qualitative methods and a survey among users of the AOB.Footnote 6 This approach yields a complex picture of the work of the AOB and its effects. In this paper, we will focus on the results of our survey. Preliminary results of the qualitative research were used for constructing the questionnaire for the user survey.Footnote 7 Also, several questions were borrowed from Naomi Creutzfeld, who kindly shared the questionnaire that she had developed for her own research. We pretested the questionnaire with four complainants (varying age, gender, social status and type of complaint) with whom we also conducted qualitative interviews.

The survey was carried out in May and June 2018. In sum, 8,274 users of the AOB were contacted: 6,258 users were sent an e-mail with a link to an online survey (all persons who filed a complaint in the year 2017 and who had provided an e-mail address) and 2,016 users were sent a hard-copy questionnaire by post survey (all persons with a complaint between February and April 2018). This – more challenging and resource-intensive – double strategy allowed us to reach also hard-to-reach groups such as persons not comfortable with digital technologies or even prisoners, as our analysis shows. In sum, we received 1,914 replies, which corresponds to an overall response rate of 23 per cent. Participation in the survey was anonymous; the research team did not receive any personal data of users since the dispatch was carried out by the AOB based on its own database of complaints.

The results discussed in this paper are based on frequencies and correlations with regard to the users’ sociodemographic profiles. Other topics covered in the survey, such as users’ expectations and experiences regarding the AOB's work, cannot be discussed within the scope of this paper.

4 Complementary approaches in the study of access to (administrative) justice

In this paper, we build on existing research on inequalities in access to justice and on the institutional measures aimed at counteracting such inequalities. From the beginning of the access-to-justice movement in the 1960s and 1970s, researchers have been interested in the role of social structures in hampering equal access to legal remedies. In the late 1970s, as part of the US-American Civil Litigation Research Project, Miller and Sarat (Reference Miller and Sarat1980) investigated how social inequality, power and subjective perceptions affect individuals’ understandings of so-called ‘justiciable events’ and their willingness to mobilise law in order to remedy these problems. At the same time, research on access to justice was conducted in many European countries and legal-aid offices opened in different national contexts (Blankenburg and Kaupen, Reference Blankenburg and Kaupen1978; Garth and Cappelletti, Reference Garth and Cappelletti1978; Lascoumes, Reference Lascoumes1978). However, in these works, access to justice tends to be used as a synonym of access to civil justice. Implicitly, researchers consider access to civil courts and lawyers as the main entry point for getting justice. Consequently, the empirical domain of conflicts that involve individuals and the state rather than only individual parties are rare and research on access to administrative justice has been particularly scarce (Halliday and Scott, Reference Halliday, Scott, Cane and Kritzer2010). When studying access to administrative justice, as we do in this paper by considering the case of an ombuds institution, we have to carry insights from the access-to-civil-justice literature over to the domain under study.

In this paper, we follow Albiston and Sandefur's (Reference Albiston and Sandefur2013) call to integrate bottom-up and top-down approaches – namely the demand and the supply sides – to access to justice, applying it to the specific area of administrative justice. We thus first discuss key findings of the literature on individuals’ claiming behaviour in relation to their socio-economic characteristics. In a second step, we focus on institutional design and outreach measures, in particular face-to-face legal consultation and legal disputes in TV shows, as these are relevant to our case-study.

4.1 Bottom-up approaches: social characteristics of complainants

Reviewing more than fifty years of research on access-to-civil-justice literature, Sandefur (Reference Sandefur2008) distinguishes between top-down and bottom-up approaches to access to justice. Bottom-up scholars analyse people's experiences of conflicts and focus on their social and legal histories and socio-economic characteristics. Scholars have shown that gender, socio-economic status and race play important roles in explaining how people respond to justiciable events (Genn, Reference Genn1999; Sandefur, Reference Sandefur and Pleasence2007; Reference Sandefur2008). Other factors influencing claiming behaviour include differences in people's perceptions (Lind et al., Reference Lind2000; Vidmar and Schuller, Reference Vidmar and Schuller1987) or social interactions and relationships as well as symbolic and structural factors (Bumiller, Reference Bumiller1992; Erlanger et al., Reference Erlanger, Edelman and Lande1993; Morrill and Rudes, Reference Morrill and Rudes2010; Quinn, Reference Quinn2000).

Existing studies on the users of ombuds institutions suggest that the socially disadvantaged are less likely to appeal to the institution (de Asper y Valdés, Reference de Asper y Valdés and Reif1999; Roosbroek and de Walle, Reference Roosbroek and de Walle2008). As Sandefur explains with regard to access to justice in general:

‘in capitalist contexts, problem occurrences increase with household income and/or education, in part because people of higher socioeconomic status engage in more consumer and investment activity’. It is also known that ‘once people confront problems, class is predictive of how they will respond, but the patterns are complex.’ (Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008, p. 346)

People with a higher socio-economic status are more likely both to take action in response to a problem and to resort to the law in doing so than are people with a lower status (Michelson, Reference Michelson2007; Miller and Sarat, Reference Miller and Sarat1980; Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008). However, there is also evidence that middle-income groups are most active about their problems, the lowest- and highest-income groups being less likely to turn to law or seek out other advice (Genn and Paterson, Reference Genn and Paterson2001; Silberman, Reference Silberman1985). The most common explanation for socio-economic differences in recourse to law is found in a calculation that balances the costs and resources, implications and expected returns of certain actions (e.g. Michelson, Reference Michelson2008). Other scholars have shown, however, that these reasons do not fully explain class-stratified patterns. Factors associated with social status, such as feelings of powerlessness or entitlement, but also differences in previous experiences with legal problems can play a key role in patterns of class differences concerning action and inaction (Gilliom, Reference Gilliom2001; Pleasance et al., Reference Pleasance2003; Pleasence, Reference Pleasence2006; Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008). Thus, legal literacy and (lack of) administrative knowledge – both potentially related to education and professional activity – can also have important effects on people's behaviour.

Several researchers have investigated gender-related issues in access to justice. According to Sandefur (Reference Sandefur2008), forces limiting the mobilisation of law by women exist at different levels. With regard to harassment, for instance, women often report believing that they should have been able to control the situation themselves or that their situation cannot be addressed by the law (Bumiller, Reference Bumiller1992; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2004). At a more general level, Hatıpoğlu-Aydın and Aydın (Reference Hatıpoğlu-Aydın and Aydın2016) point out that the ostensibly neutral formulation or even overtly male-oriented formulation of legal regulations may eventually end up working against women due to the different life experiences of men and women. According to Mossman (Reference Mossman1994), the gender-neutral language of law tends to conceal sexist preferences. Also, the feminisation of poverty and the public/private dilemma – women are more often confronted with problems that are considered ‘private’ matters – may play a role in reduced access to civil justice for women. Hatıpoğlu-Aydın and Aydın (Reference Hatıpoğlu-Aydın and Aydın2016) contend that male police officers, judges and prosecutors also contribute to hampering women's access to justice. However, these studies mainly concern access to civil justice. So far, we lack explanations for the gender difference in the access to administrative justice. At the same time, it has been suggested that legal consciousness and legal mobilisation can vary between different social contexts and areas of law (Ewick and Silbey, Reference Ewick and Silbey1998). It is therefore uncertain whether we can translate these findings into the area of administrative justice.

4.2 Top-down approaches: institutional and redress design

In contrast to the above-cited research, top-down research explores how certain aspects of legal systems or institutions influence people's likelihood of appealing to the law and their experiences thereof (Albiston, Reference Albiston2005; Anderson, Reference Anderson2003; Mayhew, Reference Mayhew1975; Sterett, Reference Sterett, Sarat and Scheingold1998):

‘Contemporary top-down studies explore aspects of the organization of civil justice institutions that may affect who is able to turn to law, through what avenues, for what purposes and with what results, such as the complexity of legal procedures … and the provision of legal services.’ (Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008, p. 343)

This stream of research also includes studies on the effects of different legal procedures on people's abilities to use law to solve their problems, particularly in the field of ADR.

With the concept of ‘redress design’, Le Sueur (Reference Le2012) focuses on changes within processes and institutions in the context of public administrations and public law systems; this includes ‘activities which involve devising and reforming the ways in which people's grievances against public bodies are dealt with across the whole administrative justice landscape’, among others, ombuds institutions (ibid., p. 18). Le Sueur (Reference Le2012, p. 19) points out that ombuds institutions participate in redress design in different ways, such as by issuing statements on good practice for administrators, by proactively engaging in the public debate or by using leeway in interpreting the statutory framework within which they work. The author shows that the overall redress design produces different degrees of change (from small-scale to paradigm shifts), that a wide range of actors are involved in these processes and that there are a number of different drivers for designing. He argues that the redress design needs to be recognised as a distinct activity by the professionally involved actors since ‘heightened awareness may also enable designs to be more consistently informed by basic principles of constitutional propriety and administrative justice’ (ibid., p. 19).

In a similar fashion, Albiston and Sandefur (Reference Albiston and Sandefur2013) have argued that what they call ‘institutional design’ has an impact on ‘sustainability, independence, effectiveness, and inequality in access to representation’. For example, delivery systems that rely on the private bar to provide representation will neither reach all groups of society nor be a good way to address systemic issues related to inequality. In addition, such delivery models, understood as ‘emergency room representation’, due to limited resources often apply income eligibility criteria, which hampers access for many individuals. Another important factor is that the sources of financial support influence the effectiveness of a service; for instance, state-funded services are typically vulnerable to political attacks that may lead to cuts in funding or restrictions on activities.

In her analysis of legal and non-legal institutions of remedy, Sandefur (Reference Sandefur2009, pp. 976–977) thus argues that institutional design is ‘the fulcrum point in equalizing access to justice’. She compares UK and US institutions of remedy – formal legal (e.g. courts) and non-legal institutions (e.g. ombuds) as well as auxiliaries (e.g. advice agencies) – with regard to their powers and services. Sandefur distinguishes relatively inclusive and relatively exclusive institutions. On the one hand, there are those that ‘draw in a greater share of the population, so everyone is likely to do something to try to resolve their justice problems’ (ibid., p. 975); they include, for instance, expansive legal aid through formal institutions and well-established national advice providers as well as many offers by non-lawyers. On the other hand, there are institutions that ‘discourage action both in general and on the part of certain groups – the poor in particular’ (ibid., p. 976), characterised, for instance, by limited legal aid through formal institutions and a strong lawyer monopoly on legal advice. According to the author:

‘institutions of remedy shape – or, more aptly, create – inequality in access to substantive justice. By shaping how people handle their justice problems, institutions shape both inequality in access to different routes to solving justice problems and inequality in whether or how those problems are resolved.’ (ibid., p. 976)

Following Albiston and Sandefur (Reference Albiston and Sandefur2013), outreach measures can be considered as a key element of ‘institutional design’ and as an important lever for equal access to justice. The concept of ‘outreach’ lacks a clear definition, but several key elements have been pointed out. Often, ‘outreach refers to services that are made available in locations where they would not usually be accessible’, in geographical proximity to the target group (Buck, Reference Buck, Buck, Pleasence and Balmer2009, p. 73). Client engagement and relationship building are other relevant components of outreach, which is often aimed at vulnerable, disadvantaged or hard-to-reach groups. As Greiner (Reference Greiner2016) puts it, outreach contributes to generating clients for providers of civil legal services providers.

Following this line of reasoning, in our case-study, two elements of the AOB's institutional design can be considered as outreach measures: consultation days and the TV broadcast. To what extent do these two measures impact the institution's accessibility? Before we tackle this question through empirical investigation, we have to examine whether a potential impact can be expected both from direct interaction with an ombudsperson at a consultation day and from the experience of the ombuds’ engagement towards citizens through a weekly TV broadcast. We therefore situate these two outreach measures in two different strands of research: while the consultation dayFootnote 8 can be explored from the perspective of face-to-face encounters in bureaucratic and legal-advice settings, the weekly TV broadcast is best understood through research on legal disputes in television shows.

4.3 Outreach measures I: face-to-face encounters and legal consultation

There is a long tradition of research on bureaucratic face-to-face encounters (Bartels, Reference Bartels2015; Dubois, Reference Dubois2016; Goodsell, Reference Goodsell1981; Lipsky, Reference Lipsky2010; Prottas, Reference Prottas1979). Public encounters are often studied from the perspective of ‘street-level bureaucracy’ – a term coined by Lipsky in 1969: ‘Street-level bureaucrats … are those men and women who, in their face-to-face encounters with citizens ‘represent’ government to the people’ (Lipsky, Reference Lipsky1969, p. 1). Typically based on ethnographic data, scholars have researched, for instance, how citizens or applicants and public professionals negotiate the meaning of law and thus influence street-level decision-making in individual cases (Johannessen, Reference Johannessen2019; Dahlvik, Reference Dahlvik2018).

In the field of access to justice, and when it comes to legal advice and ombuds activities, however, face-to-face interaction is rarely studied.Footnote 9 Some scholars have compared the effects of telephone or online services to personal encounters in the context of legal-advice centres (Balmer et al., Reference Balmer2012; Harris, Reference Harris2020; Smith and Paterson, Reference Smith and Paterson2014). Their findings suggest that the shift away from face-to-face consultation bears some dangers. As Balmer et al. (Reference Balmer2012) point out, persons aged under eighteen and persons with an illness or disability more often use face-to-face legal-aid services than other groups. They find that not only the individuals’ demographic characteristics, but also the types of problems addressed in telephone consultations are significantly different. Focusing on homeless people and advice on welfare benefits, Harris (Reference Harris2020, p. 143) finds that ‘the current shift to digitization fails to recognize the variation and complexity surrounding homeless people's use of technology’. Instead of putting people in homogenising categories, advice centres need to have a nuanced understanding of people's uses of technology, she argues. In their study on face-to-face legal services and their alternatives, Smith and Paterson (Reference Smith and Paterson2014) reach the conclusion that digital delivery cannot replace face-to-face services: ‘Put starkly, clients will be lost if consulting rooms are closed and people are expected to use the phone or the internet’ (ibid., p. 83). With this paper, we aim to contribute to the underresearched field of face-to-face interaction in access to justice and its concrete effects in the case of the ombuds institution.

4.4 Outreach measures II: legal disputes in TV shows

The interaction between the legal system and the media is a well-established field of research (Hans, Reference Hans1990; Machura, Reference Machura2017; Sarat, Reference Sarat2011). Rapping (Reference Rapping2003) shows that the relationship between the law and the media is characterised by ‘a shared storytelling function’: while the legal system provides camera-ready stories, the media provide the corresponding narrative frames. Beside legal dramas, legal comedies and legal procedurals, Robson (Reference Robson2006) has recently drawn attention to a rather rare but for our purpose interesting genre: legal reality shows. These shows either take place in settings and with participants that are actually part of the justice system in order to educate or encourage the general public (Robson, Reference Robson2006, p. 342) or, as in the case of the AOB TV show, ‘participants are appearing in a dispute adapted for the television format’ (ibid., p. 342). Scholars have highlighted that such adaptions typically go hand in hand with the privatisation of television channels and an increased focus on entertainment (Oulette, Reference Oulette and Sarat2011; Robson, Reference Robson2006); in the case of the AOB, however, the weekly show is hosted by the public broadcasting company.

Which effects does the appearance of legal matters in TV shows have on viewers? Previous research has shown effects mainly in the fields of medicine and crime, and based on fiction. For instance, in the context of criminal trials, studies have shown that legal professionals increasingly believe that jurors have unrealistic expectations for forensic evidence to be included although it is in reality often unavailable (Cole and Dioso-Villa, Reference Cole and Dioso-Villa2009; Mancini, Reference Mancini2011). This phenomenon, called the ‘CSI effect’, seems to stem from the fact that jurors typically gain their information about scientific evidence through crime television shows, such as Crime Scene Investigation (Tyler, Reference Tyler2006). As Wood (Reference Wood2018) argues, legal TV shows establish specific forms of ‘televisual legal consciousness’. She includes the form and genre of such shows in her analysis to study the relationship between television, law and everyday life. According to Wood (Reference Wood2018, p. 593), legal TV shows ‘enable real-world intensities to break through and even upturn legal frames via their televisual frames – whether that's through humour, emotion or anger’. Such shows, in which the dynamics of reason and emotion are ‘performed and played out together’, can thus influence citizens’ legal consciousness.

In short, these research findings suggest that TV shows do affect people's perceptions and understandings of law and legal procedures, and also influence how people act within the law. However, this interaction between the media and the law has not yet been studied with regard to matters of administrative justice (cf. Eberle, Reference Eberle1996, for the German context). Also, the question of whether TV shows that feature legal content can function as an outreach measure to lower the threshold and diminish inequalities in access to legal institutions has not been investigated. The case of the AOB is interesting in that its weekly TV broadcast is a non-fiction show, where the ombudspersons present actual, carefully selected cases, which should ‘give insight into the work of the AOB, pique the curiosity of the viewers and provoke their empathy, inform and entertain’ (Kastner, Reference Kastner2018, p. 62). In other words, the AOB explicitly conceives of the TV show as a means to make the institution more accessible. Thus, by studying the effects of this show, we can address two shortcomings of the above-mentioned literature: we analyse whether the TV show affects viewers’ actions towards law within the so-far neglected field of administrative justice and whether they can help to reduce inequalities in access to justice.

5 Results of the study

In the following, we explore to what degree the population of AOB users reflects the characteristics of the Austrian society at large, regarding variables that have been identified as relevant in previous research on access to justice. As we will see, statistically significant differences on characteristics such as gender or socio-economic status indicate inequalities in the access to the ombuds service, and thus to administrative justice. We will examine possible explanations for these differences. In a second step, we investigate the impact of the AOB's two unique outreach measures to understand how they affect the composition of the complainant population.

5.1 The social structure of the complainant population

In order to understand who actually addresses the AOB, we first analyse whether there are differences between the group of AOB users and the general Austrian population with regard to age, gender, citizenship, education, family status, form of subsistence and (former) professional position.Footnote 10 We find significant differences: individuals with certain characteristics are overrepresented and access to the institution is thus unequal. In the following, we examine possible explanations based on the literature, partly supported by our qualitative research findings.

5.1.1 Gender

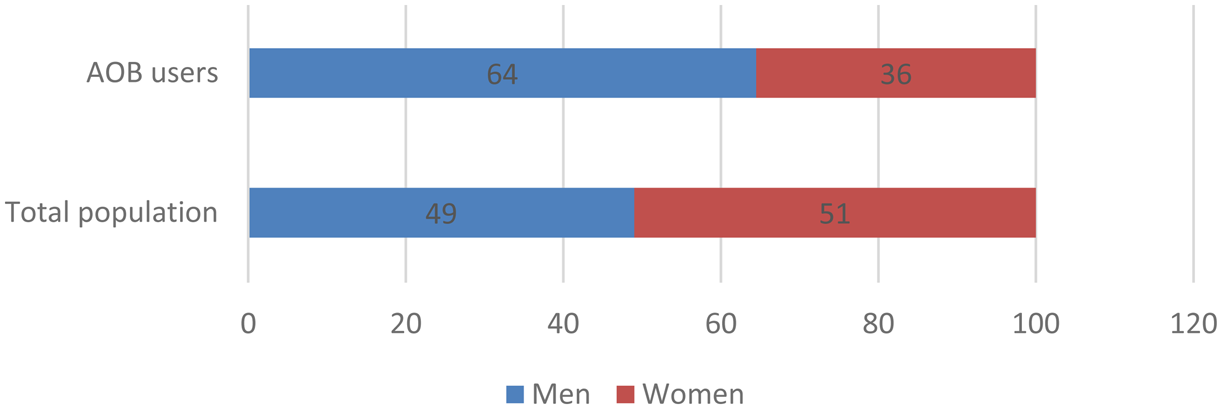

Our data show significant differences between the sociodemographic characteristics of the AOB users and the total Austrian population concerning gender. Figure 1 shows that female users are clearly underrepresented and male users are overrepresented compared to the total Austrian population: only 36 per cent of AOB users are women (vs. 51 per cent of the population). These findings confirm those of studies on the users of ombuds institutions in other national contexts, where women have been shown to be significantly underrepresented, with some notable exceptions (Hubeau, Reference Hubeau, Hertogh and Kirkham2018). They also confirm existing studies on access to administrative courts: in France, for instance, around two-thirds of complainants are men (Spire and Weidenfeld, Reference Spire and Weidenfeld2011; Weidenfeld, Reference Weidenfeld and Spire2008).

Figure 1. Comparison of gender as percentages. Source: Own calculations based on data from Statistik Austria, Central Register (2017b) and own survey (N = 1,628).

These findings speak well to the existing literature on gender-related issues in access to justice. Several authors have highlighted that forces limiting the mobilisation of law by women exist at different levels (Bumiller, Reference Bumiller1992; Nielsen, Reference Nielsen2004). As Hatıpoğlu-Aydın and Aydın (Reference Hatıpoğlu-Aydın and Aydın2016) explain, male officers may also play a role in hampering women's access to justice. This could also be a factor in the case of the AOB, where all three ombudspersons are currently men.Footnote 11

An explanation for the underrepresentation of women could also lie in the division of labour regarding ‘paperwork’ within opposite-sex-couple households. Time-budget studies on the Austrian context show that the use of time and participation in household activities, including paperwork, is highly gendered. Typically, more women do paperwork then men, but overall men spend more time on this kind of workFootnote 12 (Ghassemi and Kronsteiner-Mann, Reference Ghassemi and Kronsteiner-Mann2009). At the same time, in an ethnographic study set in the French context, Siblot (Reference Siblot2006) shows that women often perform the repetitive, invisible and less valued tasks, such as submitting documents to the authorities, whereas men take care of tasks such as dealing with tax administrations and writing letters to institutions, which are often perceived as more demanding. This gendered division of labour suggests that men could be more inclined to write a complaint letter or to complain in person. Additionally, in the context of the French tax administration, Spire (Reference Spire2018) has recently shown that gender interacts with social class: whereas in the working classes, women more often take care of paperwork, men tend to take over these activities in the middle classes and especially in higher classes. This is relevant to our study since an important number of ombuds users pertain to the middle and upper classes.

This kind of division of labour might also be an explanation for our own findings: our data show a significant difference in the frequency of contact with authorities between women and men (no figure). Women have slightly higher response rates in the ‘several times a month’ category (16 vs. 14 per cent), while men selected the ‘several times a year’ category more often (66 vs. 56 per cent). Women also more often report that they never have contacts with administrations (17 vs. 11 per cent), which might be one of the reasons why they are also underrepresented at the ombuds institution.

On a more general level, significant gender differences regarding experience with the law in different areas (no figure) may also explain the gender gap. Men have statistically significantly higher response rates in the following categories: appealed against an administrative decision, been party to a legal proceeding, contacted an arbitration body and filed a complaint. In other words, they have more experience with litigation in general. These results seem to match the existing literature on gender inequalities regarding access to civil justice. Only a small part (13 per cent) of the overall complainant population is constituted by people who state that they have no experience with law, such as they have never filed a complaint or been involved in litigation. These people hesitate to appeal to the formal legal system and yet they reach out to the ombuds institution, probably because they conceive of it as an alternative path to administrative justice.Footnote 13

5.1.2 Age

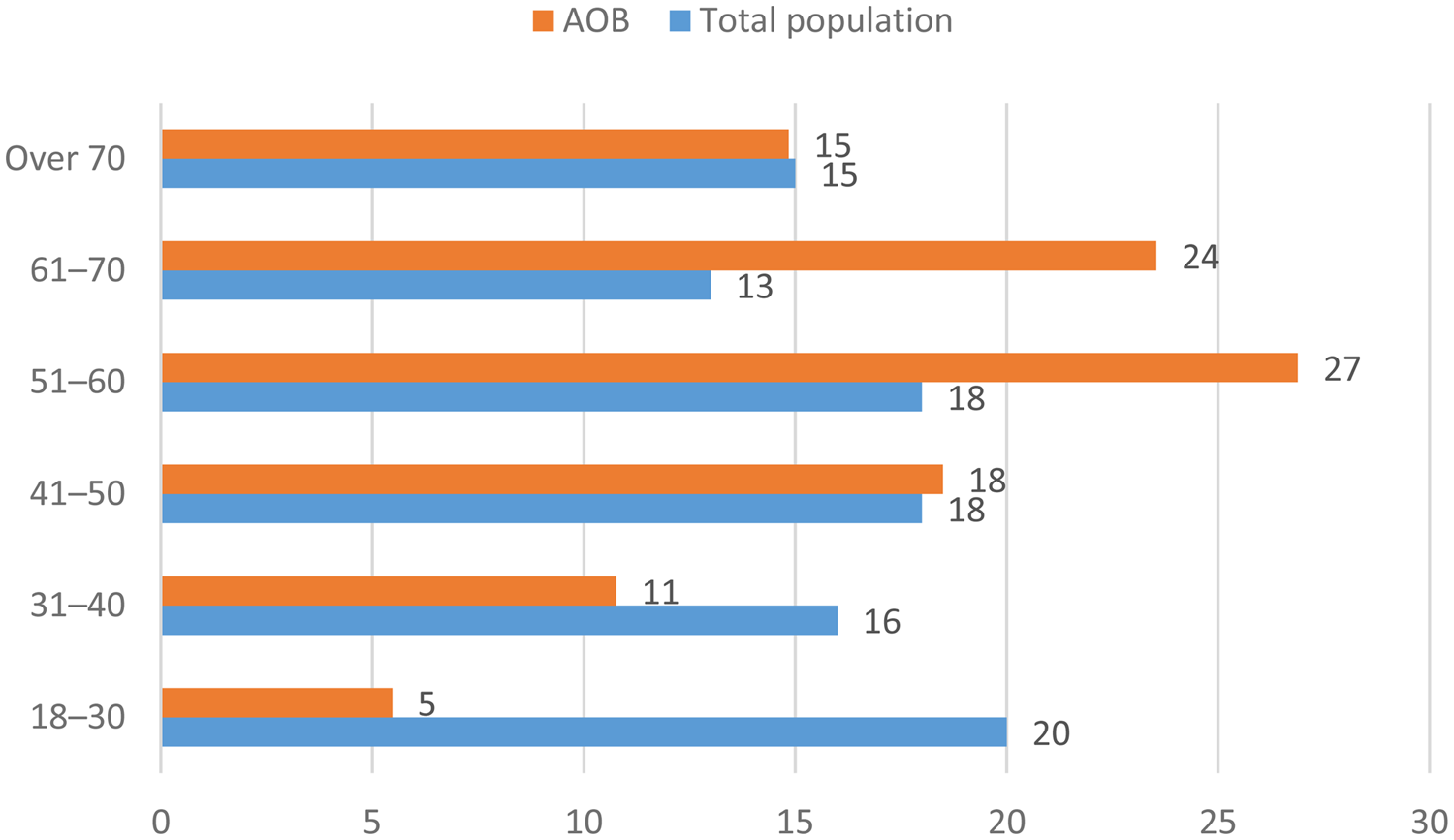

In our survey, we found significant differences between our sample and the overall population regarding age. While persons aged under thirty are strongly underrepresented compared to the overall population (20 vs. 5 per cent), those aged between forty-one and seventy are highly overrepresented (Figure 2). This seems to be typical of users of ombuds institutions, as other scholars have reported similar findings (Creutzfeldt, Reference Creutzfeldt2016; Hertogh, Reference Hertogh2013).

Figure 2. Comparative user age as percentages. Source: Own calculations based on data from Statistik Austria, Central Register (2017b) and own survey (N = 1,644).

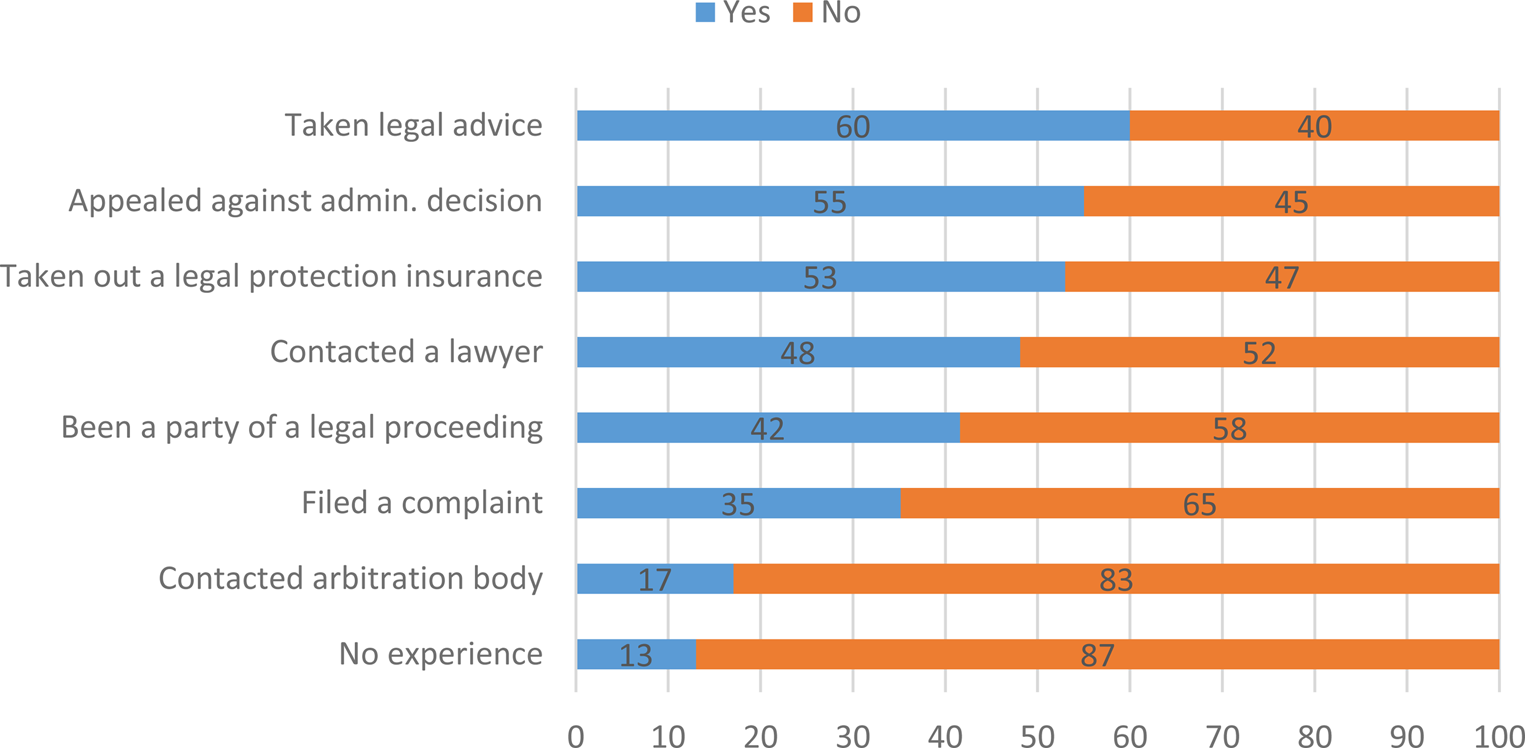

One reason for this might be that younger individuals have less experience with the law in general; many might develop a stronger legal consciousness later in life. The literature – again, mostly regarding civil-law matters – has shown that past experiences with law can have a strong effect on the type of legal consciousness that individuals will mainly draw upon when deciding whether or not to engage in litigious activity (Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008; Vigour and Dumoulin, Reference Vigour and Dumoulin2017). In our data, we see a clear trend wherein people who address the AOB already have a great amount of experience with the law (Figure 3). The majority of users have already taken legal advice (60 per cent), taken out a legal-protection insurance policy (53 per cent) and appealed an administrative decision (55 per cent). Only a small fraction of AOB users (13 per cent) indicate that they have no experience with the law. However, compared to the other age groups, those aged under thirty have the highest response rate in the ‘no experience with the law’ category (no figure).Footnote 14

Figure 3. Experience with the law as percentages. Source: Calculations based on own survey (N = 1,399).

A second possible explanation is that younger people have less knowledge about the ombuds institution. In 2015, a representative survey commissioned by the AOB showed that only half of the population under the age of thirty-four had heard of the AOB whereas three-quarters of those aged sixty years and older were familiar with it. Patterns of media consumption certainly go some way towards explaining this. When asked how they had heard about the AOB, most citizens reported having watched the weekly ombuds TV show. This show is thus a prominent channel of communication with the population, but we see a statistically significant association between age and frequency of TV broadcast watching. In our survey, we see that whereas 47 per cent of individuals aged sixty-one and older watched the show weekly or several times a month, 43 per cent of those aged forty and below never or no longer watched it; 36 per cent watched it only a few times a year (no figure). This finding might also reflect the fact that the younger generations watch less TV than elderly citizens.Footnote 15 In addition, the fact that ombudspersons’ average age at entry to the AOB is fifty-five might impact the appeal of the institution for younger people.

5.1.3 Socio-economic status

Concerning socio-economic status, interviewed AOB staff tend to highlight the institution's low threshold of access and typically believe that there is a good mix of users. They often find that the AOB reaches all layers of society, thanks to the possibility of filing a complaint in person or via e-mail.

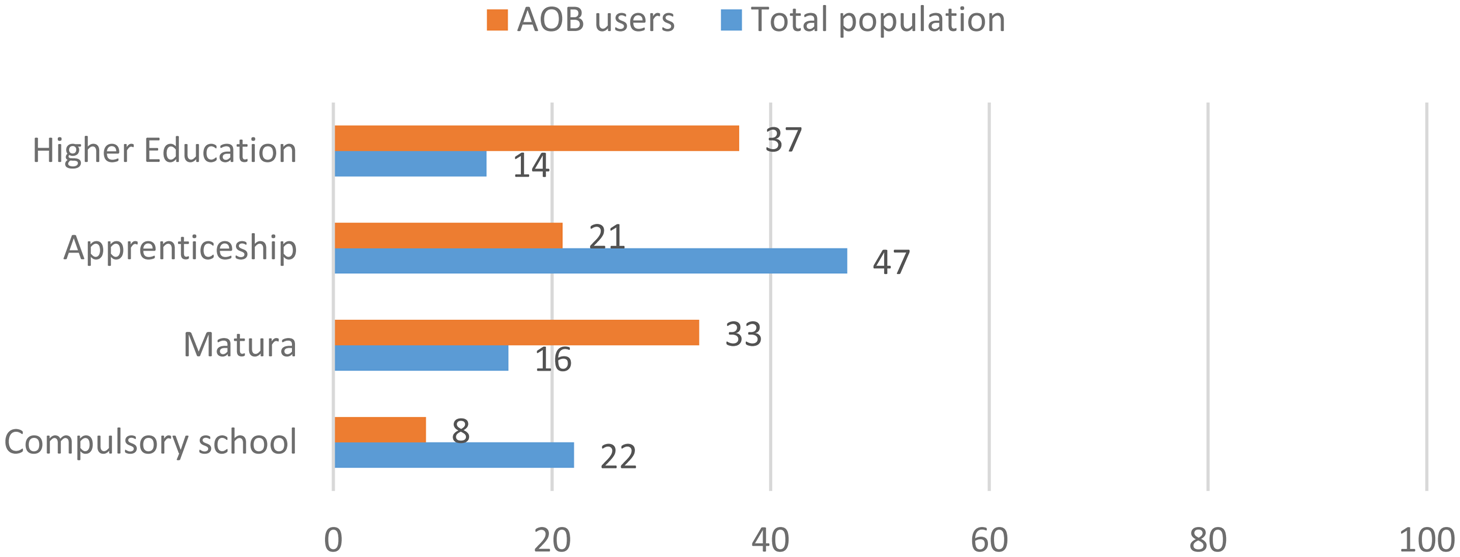

Our survey data, however, provide counter-evidence for this, in line with previous research findings on the accessibility or user population of other ombuds institutions (Figure 4). Individuals who attended higher education are strongly overrepresented (37 vs. 14 per cent), whereas those with a high-school level are clearly underrepresented (8 vs. 22 per cent) compared with the total population. Similarly, people who pursued apprenticeships or vocational training are underrepresented in the group of AOB users (47 vs. 21 per cent). These differences regarding education are statistically highly significant.

Figure 4. Comparison of highest education as percentages. Note: ‘Matura’ is the general qualification for university entrance. Source: Own calculations based on data from Statistik Austria, Labour Force Survey (2017a) and own survey (N = 1,593; p = 0.000).

We also found a significant difference in the frequency of dealings with authorities between persons with lowerFootnote 16 and higherFootnote 17 education levels. Compared to the respective other group, those with lower education levels are more represented in the ‘never’ categories (17 vs. 10 per cent), while those with higher education levels are more represented in the ‘weekly’ category (12 vs. 6 per cent, no figure).

In line with the existing literature, we also find significant differences in experience with the law with respect to education. Whereas 18 per cent of individuals with high-school level or vocational training state that they have ‘no experience with the law’, this is the case of only 9 per cent of those who graduated high school or attended higher education (no figure).

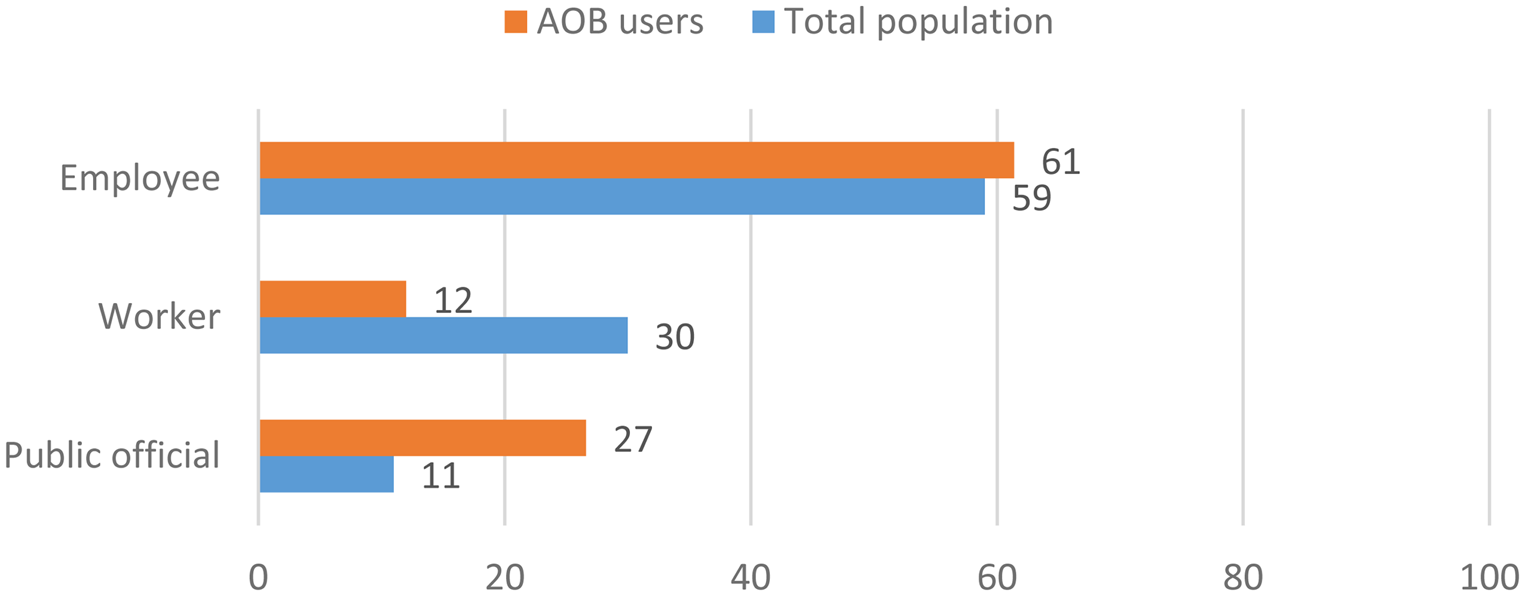

Also, current and former public officials are clearly overrepresented in the group of AOB users – almost double the percentage of the total population – while workers are underrepresented by around half (Figure 5). This goes hand in hand with our findings on differences in terms of socio-economic status. Additionally, when considering taking out a legal-protection insurance policy as an indicator for legal consciousness, we found significant differences with regard to these individuals’ professional positions, with proportions of policy subscribers varying between workers (40 per cent), employees (57 per cent) and public officials (62 per cent) (no figure). The legal-protection-insurance variable also correlates with the type of professional activity: while the lowest rates are found with persons with an ancillary activity (35 per cent), the rates increase with middle activity (e.g. ‘regular’ employee; 56 per cent) and higher activity (e.g. management level; 58 per cent). Differences concerning legal-protection insurance can also be observed between foreign and Austrian citizens: 56 per cent of those with Austrian citizenship have taken out such an insurance compared with only 27 per cent of foreign citizens (no figure).

Figure 5. (Former) professional position as percentages. Source: Own calculations based on data from Statistik Austria, Labour Force Survey (2017a) and own survey. The available data from Statistik Austria of the Labour Force Survey relate to people in employment for between fifteen and sixty-four years, and allows therefore only a superficial comparison to our own survey (N = 1,067; p = 0.000).

Last but not least, there is also a statistically significant difference between Austrian and non-Austrian citizens in recourse to the ombuds. Whereas 15 per cent of the population do not have Austrian citizenship, only 8 per cent of the AOB complainants are foreign citizens (no figure). This underrepresentation might also be related to the lower socio-economic status of migrants,Footnote 18 who in that sense belong to a group that is already underrepresented at the AOB.Footnote 19

Taken together, these findings seem to confirm the socio-economic inequalities in access to justice that are discussed in the literature. Research suggests that the socially disadvantaged are less likely to use legal institutions, including the ombuds (Roosbroek and de Walle, Reference Roosbroek and de Walle2008; Michelson, Reference Michelson2007; Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008). Among the factors related to social class that might affect people's behaviour are differences in previous experiences with legal problems, feelings of powerlessness or lacking a sense of entitlement as well as a lack of legal literacy and administrative knowledge (Gilliom, Reference Gilliom2001; Pleasence, Reference Pleasence2006; Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008).

While worthwhile efforts have been made towards building a solid empirical basis on the unequal access to justice from the perspective of users, we still know little about the institutional side of legal proceedings. As Sandefur asks:

‘to what extent do these patterns result from the enacted class biases and prejudices of legal professionals or public service officials, or from constraints created by how people have decided to organize legal work environments, or from facially class-neutral procedures that favour some groups over others.’ (Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008, p. 349)

There is still research to be done in these fields; in the following, we make a contribution to these open questions by exploring the effects of institutional design on access to administrative justice, focusing on two outreach measures.

5.2 Effects of the AOB's outreach measures

This section is dedicated to the question of whether the AOB's outreach measures, namely the consultation day and the TV broadcast, influence the sociodemographic profile of those who appeal to the ombuds institution. To what degree do they increase equality in the access to administrative justice?

5.2.1 The consultation day

What does the survey tell us about the uses and effects of the consultation day?Footnote 20 One of the primary motivations for going to the consultation day seems to be the opportunity to explain the problem to the ombudsperson personally rather than to a staff member: 73 per cent answered ‘I strongly agree’ and 15 per cent ‘I agree’ to the item ‘It was important for me to speak to the ombudsperson personally’. This finding confirms the assumption of several interviewees. One of the reasons might be that the ombudspersons are known especially from the TV broadcast, but also as former politicians, whom complainants might remember favourably from previous media appearances. It is thus possible that some complainants wish to put their case to one ombudsperson in particular more than to the ombuds institution as such. For them, the consultation day is a means to get in contact with that person and to secure their personal commitment, instead of having their case handled by a staff member through the ‘anonymous’ written procedure.

In order to test the hypothesis that the consultation day is a good means for lowering the threshold of access the institution and reaching people from all layers of society, as is often claimed by staff, we sought to identify variations in certain sociodemographic characteristics between consultation-day attendees and the other users. The correlation analysis reveals statistically significant differences with regard to education and type of employment (employed or self-employed). Differences pertaining to other sociodemographic variables such as gender, citizenship and family status also exist but are not statistically significant.

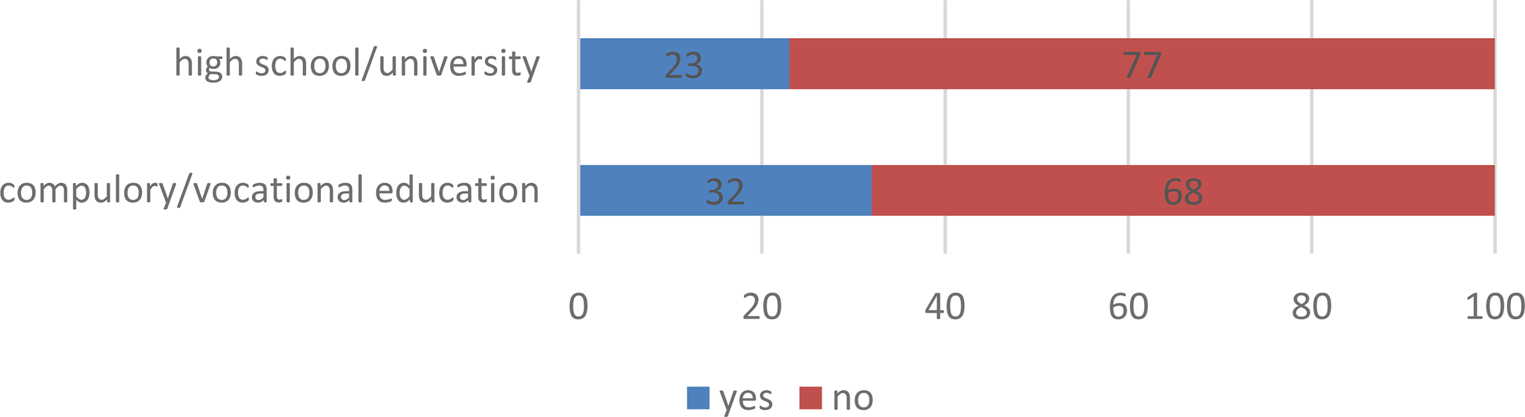

We found that less-educated complainants are more likely to attend the consultation day than those with higher levels of education. Whereas 32 per cent of high-school-level or vocational-education-level complainants submitted their problem at the consultation day, only 23 per cent of the higher educated (high-school and university graduates) did so (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Use of the consultation day as percentages. Source: Calculations based on own survey (N = 1,371; p = 0.000).

This finding could be cautiously interpreted as a confirmation of the assumption that the consultation day is conducive to improving access to administrative justice for people with lower education levels – in particular with regard to the aforementioned finding concerning the frequency of contact with authorities: those with lower education levels are more represented in the ‘never’ category, while those with higher education levels are more represented in the ‘weekly’ category. A possible interpretation is that the former regard the consultation day as an interaction that falls outside the scope of everyday bureaucracy. This matches the previous studies which have found that those with a lower socio-economic status are more likely to use front-line services because they may find it difficult to put their problem in writing and as a result to the belief that a personal appointment will increase their chance of being heardFootnote 21 (Dubois, Reference Dubois1998; Kerrouche, Reference Kerrouche2009; Pohn-Weidinger, Reference Pohn-Weidinger2014; Siblot, Reference Siblot2006).

Statistically significant differences between consultation-day attendees and other users can also pertain to type of employment, with self-employed individuals better represented in consultation days than salaried workers. A possible explanation is that the self-employed generally have more experience in negotiating and interacting with authorities (to secure permits, etc.) than employees, which might reduce barriers to making an appointment with the ombudsperson on the occasion of a consultation day (Spire and Weidenfeld, Reference Spire and Weidenfeld2011). They might also have more often observed that ‘talking to people’ is more effective than writing.

These findings highlight the importance of the consultation day as a key element of the AOB's institutional design. They suggest that potential complainants will be lost if face-to-face consultations are replaced by telephone or Internet services, as Smith and Paterson (Reference Smith and Paterson2014) have argued. In addition, we believe that, in a broader sense, the consultation day also needs to be understood in the context of an inclusive and participatory state, whereas the public encounter is traditionally a place where the asymmetric relation between citizens and the state can be observed. Some scholars, however, argue that this asymmetry is currently being reduced since the democratic demands on state institutions have intensified (Thomas, Reference Thomas2013). Previously little more than suppliants and the objects of regulatory state activity, citizens now rather tend to be understood as rights-holders, but also as shareholders of the public sector (Coats and Passmore, Reference Coats and Passmore2008). These developments seem to be conducive to the expansion of opportunities of addressing state institutions, including in face-to-face encounters.

5.2.2 The TV broadcast

Who watches the weekly AOB TV show and what implications does this have regarding access to administrative justice? A 2015 survey found that 69 per cent of the Austrian population who were familiar with the AOB were also familiar with the TV show.Footnote 22 In our own survey, 88 per cent of respondents to our survey reported being familiar with the TV show. This indicates that viewers of the show are more likely to address the ombudsperson than those who are unfamiliar with it. Complainants seem to be able to relate to the cases of maladministration that are presented on TV and take the resolute, convincing appearance of the ombudspersons as a motivation to file a complaint themselves.

Overall, elderly citizens are more likely to be attracted by the TV broadcast. Data from 2018 show that in Austria, only 47 per cent of individuals aged eighteen to twenty-four watch TV, while 77 per cent of those aged fifty-five and older do;Footnote 23 this is reflected in the viewership of the AOB's weekly broadcast (no figure). In our survey, we found that 39 per cent of people aged up to forty and under never or no longer watch the show compared with only 14 per cent of those aged sixty-one and above. Only 22 per cent of those aged under forty watch the show weekly or a few times a month compared with 44 per cent of those aged sixty-one and above. Unsurprisingly, pensioners are about twice as likely to watch the show weekly or a few times a month as working people (43 vs. 24 per cent). No significant differences in watching frequency were found with regard to professional status (position) or gender.

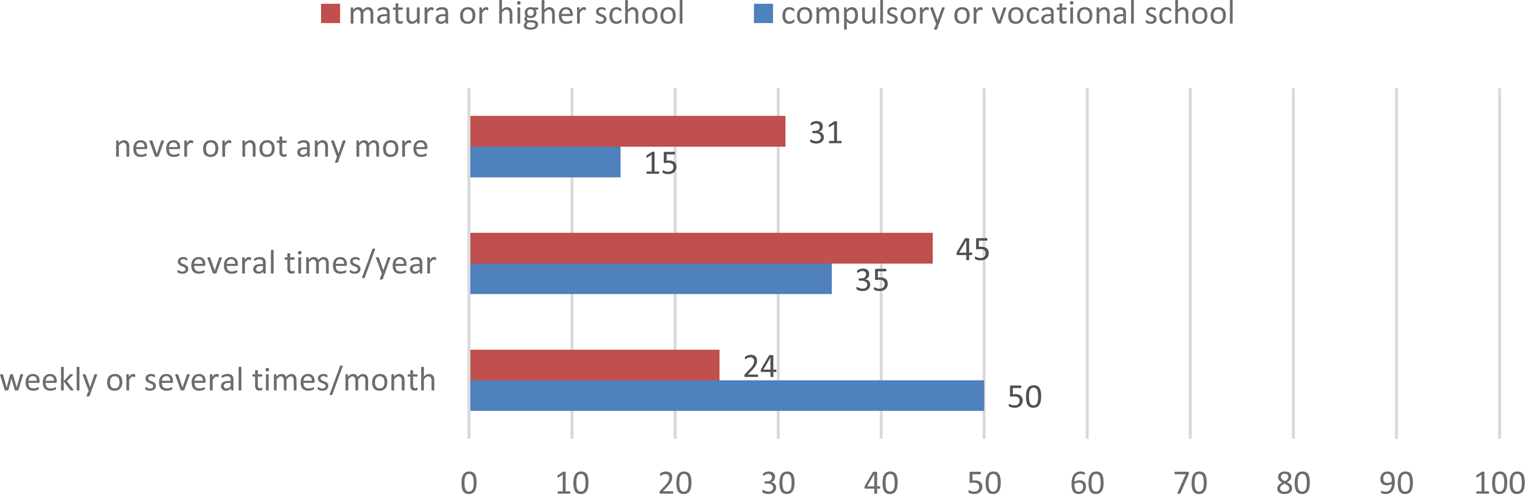

However, the education variable has a significant impact on watching frequency (Figure 7). Whereas 48 per cent of high-school or vocational-school respondents reported watching the show weekly or a few times a month, 47 per cent of those with higher education levels did only a few times a year and 30 per cent never or no longer did. This result suggests that the TV show can play a role in the decision of less-educated individuals to bring a complaint to the ombuds institution that they would otherwise have refrained from. It thus seems plausible that the AOB's TV broadcast contributes to citizens’ legal consciousness, as Wood (Reference Wood2018) has already argued in the context of legal TV shows.

Figure 7. Frequency of watching the TV broadcast and education (recoded) as percentages. Source: Calculations based on own survey (N = 1,211; p = 0.000).

The presentation of the ombudsperson as the ‘citizens’ lawyer’, who fights for the rights of the underprivileged and excluded, and the staging of case-handling as a personal meeting between the ombudsperson, the complainant and the concerned administrative authority are likely to attract a socially less privileged public, who may be more inclined as a result to come to the local consultation day or submit a written complaint. This ties in with existing research suggesting that TV shows affect individuals’ perceptions and understandings of law and legal procedures and how they act within the law (Cole and Dioso-Villa, Reference Cole and Dioso-Villa2009; Mancini, Reference Mancini2011; Tyler, Reference Tyler2006).

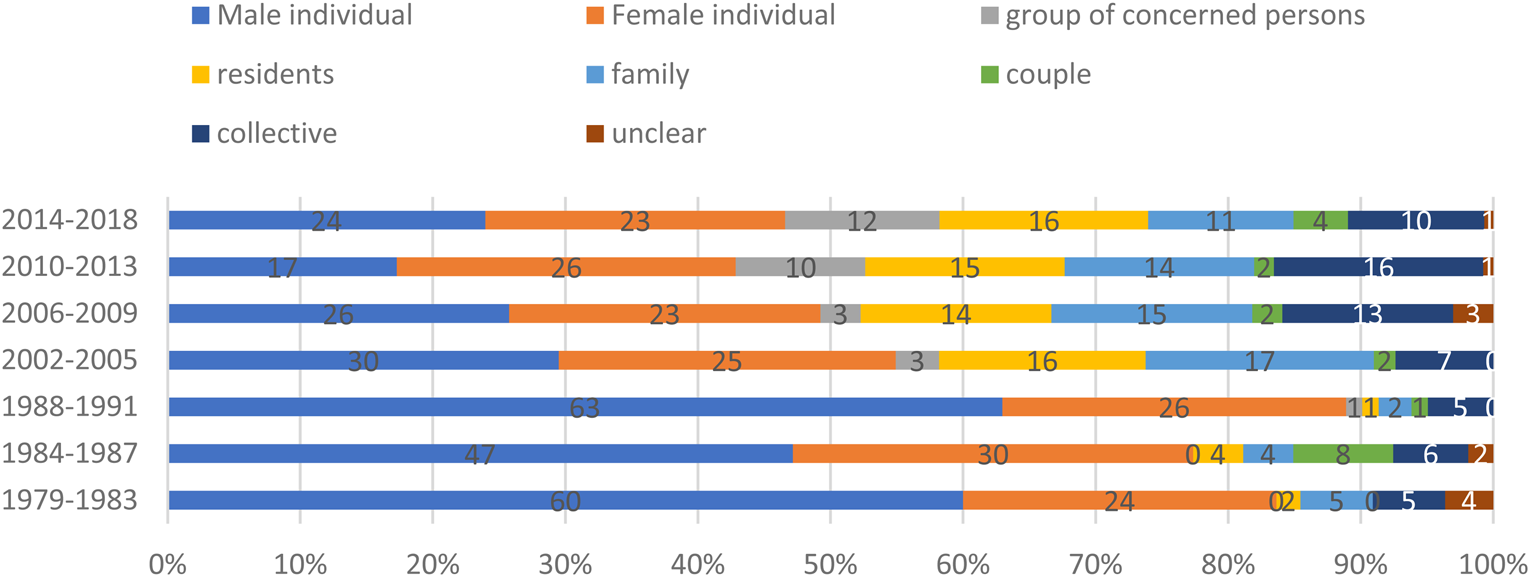

Another important question related to the effects of the TV show is: Who is actually represented in this weekly broadcast? This question might be relevant with regard to who feels addressed by the show and who can identify with the people and problems presented there. Our meta-analysis of all broadcasts from 1979 to 2018 (based on short summaries) shows major changes throughout the time. After an initial domination of individual male complainants, the proportions of other groups of users selected for the show steadily increased (Figure 8). This variety reflected the increasing use of the ombuds institution by different individuals and groups for a growing variety of problems. The share of individual female complainants has remained fairly stable over time (ranging between 23 and 30 per cent); since the relaunch of the show in 2002 after an eleven-year hiatus, proportions of both women and men in the show have varied little. Overall, the diversity currently observed in the show seems to form a good basis for addressing a broad range of social groups.Footnote 24 However, the equal distribution of men and woman since the 2000s does not seem to have had a direct effect on the structure of the complainant population, which remains predominantly male.

Figure 8. Distribution of complainants in the TV show over time as percentages. Source: Calculations based on a representative sample of the data provided by the public broadcasting company (ORF) (N = 722).

Taken together, these findings suggest that even if access to the AOB in general reproduces the social inequalities observed by the literature on the access to civil justice (Sandefur, Reference Sandefur2008) and to ombuds institutions, the TV show, as an integral part of the institutional design, can represent a means for reaching a less-educated population and inform these groups on the AOB's activities and competences. However, two significant biases remain. The first concerns citizenship: 51 per cent of foreign citizens never or no longer watch the show, as opposed to only 22 per cent of Austrian citizens (no figure). As mentioned above, the AOB generally struggles to reach non-Austrian citizens; obviously, the TV show cannot make up for that deficit. Second, the TV show does not seem to make a difference in terms of gender. Today, women and men are represented equally in the show and there are no differences in watching behaviour, but the structure of the complainant population remains predominantly male.

6 Conclusion

The aim of the paper was to explore to what extent the well-documented inequalities in access to civil justice can also be found within the field of administrative justice, and in public ombuds institutions specifically. We first investigated the sociodemographic composition of ombuds users and subsequently explored whether institutional design has a similar impact on who accesses administrative justice as in the case of civil justice. More specifically, we tested the impact of the institution's two unique outreach measures designed to curb inequalities in access to the ombuds: regularly scheduled local consultation days and a weekly broadcast on public television.

The results of our survey among users of the AOB confirm the inequalities in access to the ombuds – and thereby to administrative justice – found in other national contexts: whereas men, academics and Austrian nationals are overrepresented, women, salaried workers, people with lower education levels and foreign nationals are underrepresented. There are, however, reasons to believe that the inequalities would be even more dramatic if special outreach measures such as the consultation day and the TV show did not exist, as we find that individuals with lower levels of education are better represented in the populations of consultation-day attendees and TV-show viewers than in the overall population of users.

Returning to Sandefur's (Reference Sandefur2009) distinction between relatively inclusive and exclusive institutions, we find that in the AOB's case, both outreach measures are conceived of as creating a more inclusive institutional design. They facilitate access to administrative justice first by providing an opportunity for complainants to talk to an ombudsperson in person and second by publicly demonstrating that other people have similar problems and that someone – the ombuds – is available to address them. Both the consultation days and the TV shows seem to have at least a slight effect in improving access for people with lower education levels. Still, women appeal to the institution less than men, and non-Austrian citizens even less than Austrians, meaning that the impact of these measures is nevertheless limited and could be strengthened.

Research has shown that the reduction of inequalities in access to justice has not been tremendously successful in the past decades; a review of the literature suggests that the same social groups continue to be disadvantaged in different legal contexts in most countries. Therefore, we believe that more research is needed in particular with regard to institutional design and the effectiveness of specific measures aimed at reducing these inequalities. Studying outreach measures of ombuds institutions and their effects, also in international comparison, may prove useful for finding new approaches to improving access to administrative justice for all.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Jubiläumsfonds of the Austrian National Bank (Project Nr. 17691). The authors would like to thank the Austrian Ombudsman Board, who kindly supported the empirical research that this paper draws upon. This paper was supported by the Maison Interuniversitaire des Sciences de l'Homme d'Alsace (MISHA) and the University of Strasbourg's Initiative of Excellence.