Introduction

Sustainability is a trending issue in both the accounting and supply chain (SC) research streams. A growing number of studies have confirmed that sustainable innovation and reporting are positively correlated with firms' competitiveness in terms of value creation and cost reduction and nonfinancial assets (Assalzoo, 2021; Caiado, de Freitas Dias, Mattos, Quelhas, & Leal Filho, Reference Caiado, de Freitas Dias, Mattos, Quelhas and Leal Filho2017; Greig, Searcy, & Neumann, Reference Greig, Searcy and Neumann2021; Hermundsdottir & Aspelund, Reference Hermundsdottir and Aspelund2021; Nigri, Del Baldo, & Agulini, Reference Nigri, Del Baldo and Agulini2020).

Previous studies have suggested that the inclusion of sustainability dimensions in firms across different sectors and SCs, especially those related to technology innovation (Pigini & Conti, Reference Pigini and Conti2017; Stewart & Niero, Reference Stewart and Niero2018) and the consequent reconfiguration of processes (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2004a, Reference Jenkins2004b; Kamble, Gunasekaran, & Gawankar, Reference Kamble, Gunasekaran and Gawankar2018; Kasten, Reference Kasten2020), is diffuse. The inclusion and progressive introduction of the dimensions of sustainability, however, are also relevant in SCs that are more mature (Kamble, Gunasekaran, & Gawankar, Reference Kamble, Gunasekaran and Gawankar2018) and characterised by the extensive presence of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (Isensee, Teuteberg, Griese, & Topi, Reference Isensee, Teuteberg, Griese and Topi2020). Distinguishing between manufacturing industries thus offers the opportunity to consider the food industry significantly relevant in this context (Almerico, Reference Almerico2014; Crenna, Sinkko, & Sala, Reference Crenna, Sinkko and Sala2019; Westerholz & Höhler, Reference Westerholz and Höhler2022). Several research perspectives suggest the crucial importance of pursuing a transition to more sustainable food production (Adams, Donovan, & Topple, Reference Adams, Donovan and Topple2021; Jawaad, Hasan, Amir, & Imam, Reference Jawaad, Hasan, Amir and Imam2022).

Considering the environmental pillar, some scholars (Egilmez, Kucukvar, & Tatari, Reference Egilmez, Kucukvar and Tatari2013; Xue et al., Reference Xue, Prass, Gollnow, Davis, Scherhaufer, Östergren and Liu2019) have pointed out that when assessing manufacturing sector reporting practices, the food and beverage (F&B) sector is particularly significant for greenhouse gases, energy use and water management. Weber and Saunders-Hogberg (Reference Weber and Saunders-Hogberg2018) have indicated the relevance of water management and corporate social reporting performance for the whole F&B category and its relation to water risk management.

Regarding the social pillar, prior studies have contributed to the understanding of local communities, firms' social performance improvement and the evaluation of institutional factors for sustainability promotion (Han & Ito, Reference Han and Ito2023; Kelling, Sauer, Gold, & Seuring, Reference Kelling, Sauer, Gold and Seuring2021), which foster hunger eradication and food accessibility (Capone, Bilali, Debs, Cardone, & Driouech, Reference Capone, Bilali, Debs, Cardone and Driouech2014; Qaim, Reference Qaim2020). Limited social performance at one step of the SC has been associated with a decrease in overall performance, especially in upstream stages of SCs and in contexts with limited enforcement effects of norms and standards (Farooq, Zaman, & Nadeem, Reference Farooq, Zaman and Nadeem2021; Ogilvy & Vail, Reference Ogilvy and Vail2018).

From a managerial point of view, in the field of accounting for sustainability reporting, there are few studies concerning the F&B sector. Stranieri, Orsi, Banterle, and Ricci (Reference Stranieri, Orsi, Banterle and Ricci2019) qualitatively analyse European sustainability reports (SRs) from 53 F&B firms with mainly broad dimensions. Iazzi, Ligorio, Vrontis, and Trio's (Reference Iazzi, Ligorio, Vrontis and Trio2022) analysis of the progressive adoption of the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards highlights how presence on a listed market is a driver of corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication. Similarly, content analysis of SRs has also been conducted among Italian F&B listed companies, showing a jeopardised commitment to sustainability (Fiandrino, Busso, & Vrontis, Reference Fiandrino, Busso and Vrontis2019). Therefore, in this productive context, a gap has emerged in the analyses of SMEs' sustainability reporting propensity.

Although the focus on sustainable development criteria cannot be ascribed solely to the aspects mentioned above, the focus on (environmental) impacts has been mainly on certain categories of F&B products (Beall & Brocklesby, Reference Beall and Brocklesby2017). One of the most scrutinised branches of the F&B sector throughout the European Union is the meat and cured meat sector (Gracia, de Magistris, & Albisu, Reference Gracia, de Magistris and Albisu2011; Van der Merwe, Kirsten, & Trienekens, Reference Van der Merwe, Kirsten and Trienekens2019). On the list of the most relevant implications, in terms of sustainability impacts, are water use, animal welfare and land consumption (Amicarelli, Rana, Lombardi, & Bux, Reference Amicarelli, Rana, Lombardi and Bux2021; Forero-Cantor, Ribal, & Sanjuán, Reference Forero-Cantor, Ribal and Sanjuán2020). Another distinguishing feature of this F&B product category is the overwhelming prevalence of SMEs in the processing system (Fiandrino, Busso, & Vrontis, Reference Fiandrino, Busso and Vrontis2019; Golini, Moretto, Caniato, Caridi, & Kalchschmidt, Reference Golini, Moretto, Caniato, Caridi and Kalchschmidt2017). Nevertheless, despite the lack of attention to the sustainability reporting drivers in SMEs, their role in the promotion of ecological transition is crucial (Adams, Donovan, & Topple, Reference Adams, Donovan and Topple2021). In particular, insufficient attention has been given to both the internal and external drivers that lead SMEs to report on sustainability practices (Dienes, Sassen, & Fischer, Reference Dienes, Sassen and Fischer2016).

The contribution of this paper, then, aligns with the recent increase in the attention given to sustainability disclosure, civil society and the consequences and impact of meat and cured meat production and consumption on both the environmental and social spheres (Golini et al., Reference Golini, Moretto, Caniato, Caridi and Kalchschmidt2017; Leitch, Reference Leitch2003). The Italian context was chosen because it has one of the highest concentrations of protected designation of origin (PDO) or protected geographical indication (PGI) within the European context (ex-Regulation CE 510/2006) amid moderate consumption (OECD, 2022; OECD/FAO, 2021; Statista, 2021). In fact, according to the Ismea-Qualivita report (2022), the meat product sector of the 43 PDO and PGI products accounted for 25% of the entire category and 14% of Italian agribusiness exports in 2021, while the consumer value reached €4.85 billion. On the other hand, on the marketing side, consumers expect improvements in product quality, traceability and process transparency with regard to both the meat and cured meat product categories (León-Bravo, Moretto, Cagliano, & Caniato, Reference León-Bravo, Moretto, Cagliano and Caniato2019; Wognum, Bremmers, Trienekens, Van Der Vorst, & Bloemhof, Reference Wognum, Bremmers, Trienekens, Van Der Vorst and Bloemhof2011).

In light of the above considerations, this work aims to cover the observed research gap by considering the meat and cured meat industry and the specific link within this industry between sustainability actions and sustainability reporting. The main and original contribution of this paper is, then, an analysis of the possible determinants of nonfinancial reporting in the context of SMEs, in particular, the relationship between substantive practices aimed at a sustainable transition and sustainability communication. It is this relationship that has been insufficiently analysed in the literature focused only on reporting or sustainability performance. That is, the focus on their relationship and the potential formative role of communication in action in a sector with a high socio-environmental impact is highly significant, meriting further analysis.

This paper is structured as follows: First, the research framework is defined. Second, the methodology is elaborated, and a discussion of the results is provided. Finally, conclusions are drawn, and proposals for further studies are suggested.

Research framework

Conceptual foundation

The role of SMEs in achieving sustainability goals and pursuing a future business idea more anchored to the urgent needs of the present (e.g., respecting planetary boundaries) is generally accepted and recognised, although the scientific world disagrees on some specific elements (Dalton, Reference Dalton2020; Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino, & Venturelli, Reference Pizzi, Caputo, Corvino and Venturelli2020, Reference Pizzi, Rosati and Venturelli2021). Despite the limitations clearly attributable to smaller firms, such as a scarcity of resources, difficulty finding specialised skills, a lack of formalisation of long-term strategies and a low propensity to internationalisation, SMEs represent the foundational economic fabric of the European Union and, in particular, of Italy, historically recognised as a nation of small family businesses. Within the basket of for-profit companies, then, there is a need to explore the mechanisms underlying the choice to engage in sustainability strategies and actions, as well as the willingness to make them public and thus known to the outside world (Walsh and Sulkowski, Reference Walsh and Sulkowski2010).

While the quantitative approaches adopted in the past have provided an initial set of answers and insights on the topic, these have generated some misconceptions and scientific disagreements regarding the real commitment of SMEs to sustainability and its communication (Conca, Manta, Morrone, & Toma, Reference Conca, Manta, Morrone and Toma2021; Ogilvy & Vail, Reference Ogilvy and Vail2018). Given the lack of generalizability of the extant characteristics and phenomena attributed to SMEs, especially in a context strongly linked to national and regional traditions, e.g., Italy, and characterised by wide sectoral differences (Oduro, Maccario, & De Nisco, Reference Oduro, Maccario and De Nisco2021), it seems necessary to study the role of SMEs using qualitative methods of inquiry that can reveal the peculiarities of the focal subjects. It is through this interpretivist approach that the present study aims to investigate the relationship between SMEs and sustainability practices, specifically, between their approach to sustainability and external socioenvironmental communication.

Previous studies have focused on the drivers of better performance among SMEs (Gangi, Meles, Monferrà, & Mustilli, Reference Gangi, Meles, Monferrà and Mustilli2020; Longo, Mura, & Bonoli, Reference Longo, Mura and Bonoli2005) rather than the drivers related to wider and better communication and transparency. Thus, in light of this research gap and Jenkins's (Reference Jenkins2004a) point that in SMEs, there is a lack of formalisation of socioenvironmental responsible practices (an element capable of acting as a barrier to even socioenvironmental reporting), this research adopts the conceptual framework of Schoeneborn, Morsing, and Crane (Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020) to evaluate SMEs operating in the controversial meat (and cured meat) sector in the Italian context.

According to Schoeneborn, Morsing, and Crane (Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020), there are two possible macrocategories of linkage between sustainability communication and active sustainability practices: a representational linkage where reporting describes and illustrates what the goals and results (as well as the practices in place) are in terms of corporate sustainability and a formative linkage, which in turn entails three subcategories. In the first category, formative link (walking to talk), socioenvironmental reporting represents the last step in a process capable, however, of complementing and giving full meaning to the practices concretely in place by providing a narrative of them, ensuring access to information and data. A second possible formative link (talking to walk) involves considering sustainability reporting the first step in a broader and more complex process, capable of acting as a promoter and guide for future concrete actions. In the third link (t(w)alking), substantive sustainability actions and their reporting proceed in a parallel, coordinated and indivisible path. These categories therefore provide a starting point for analysing the practices in the focal SMEs; the peculiarities in this category of companies could allow the detection of a novel link between sustainability practices compared to those in the literature and proposed in the framework of Schoeneborn, Morsing, and Crane (Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020).

In light of this, the main objective of the present research is to uncover and shed light on the key elements in the complex and currently little-understood relationship among (1) sustainability practices, (2) sustainability reporting and (3) SMEs (Álvarez Jaramillo, Zartha Sossa, & Orozco Mendoza, Reference Álvarez Jaramillo, Zartha Sossa and Orozco Mendoza2019; Bos-Brouwers, Reference Bos-Brouwers2010; Cassells & Lewis, Reference Cassells and Lewis2011).

Sustainability factors

Based on the conceptual foundations and the objective outlined above, we have explored prior studies to obtain the main factors, at the institutional and firm level, which may have an effect on corporate sustainability practices, especially on their external communication. These factors provide a solid starting point for our analysis, which aims to build a bridge between existing scholars' works on large companies and SMEs amid the full awareness that the known relationships and reciprocal effects are not automatically generalisable to small and medium-sized companies (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2004a; Russo & Tencati, Reference Russo and Tencati2009). Hence, the factors explored and presented below are usually described as elements capable of acting as the drivers or determinants of sustainability reporting practices. However, given the specificity of this research's focus and the lack of previous studies applying these factors to SMEs, the following empirical analysis is carried out without bias, with an awareness SMEs could also play a possible role, as barriers and deterrents, between sustainability actions and sustainability reporting.

Institutional factors

Sustainability reporting determinants can vary due to several causes, such as the economic development of institutional context or the normative approach (Aureli, Del Baldo, Lombardi, & Nappo, Reference Aureli, Del Baldo, Lombardi and Nappo2020; Belal, Reference Belal2000). Alshbili, Elamer, and Moustafa (Reference Alshbili, Elamer and Moustafa2021) have considered institutional factors to determine those that are the most impactful in developing countries, namely, insufficient awareness and knowledge, the absence of legal requirements, the lack of governmental motivation and the fear of change. Such factors are expected to be more mitigated in the Italian context due to the influence of European (Directive 2014/95/UE) and national (Legislative Decree 254/2016) regulations that oblige certain firms or groups to implement nonfinancial reports. In this analysis, we have identified four main factors, namely, normative context, coordination, the basket of hard and soft competences and stakeholder expectations and needs (see Table 1).

Table 1. Factors and their main references

The literature on company reporting initiatives has explored the issue of sustainable reporting, highlighting different instruments at the country level and in terms of their span of analysis. In particular, Jensen and Berg (Reference Jensen and Berg2012) show that companies producing an integrated report are different from traditional sustainability reporting companies with regards to several country-level determinants. Various legal systems and corporate governance structures have been shown to impact sustainability reporting engagement by Miniaoui, Chibani, and Hussainey (Reference Miniaoui, Chibani and Hussainey2019). In particular, a substitutive effect on reporting, between country-level governance and the regulatory environment, has been demonstrated (Ernstberger & Grüning, Reference Ernstberger and Grüning2013). This assumption may be enforced by the vital role that institutional networks, forums, standards and nongovernmental organisations play in developing countries and emerging markets (Ali & Frynas, Reference Ali and Frynas2018; Neumayer & Perkins, Reference Neumayer and Perkins2004). In developing countries, regulation fragmentation, a limited sustainability culture and the need for a legitimated actor that supports the institutionalisation of normative models are considered the leading drivers of nonfinancial reporting (Negash & Lemma, Reference Negash and Lemma2020). Vollero, Conte, Siano, and Covucci (Reference Vollero, Conte, Siano and Covucci2019) have also underscored the relevance of the industry involved in an analysis, highlighting differences, in particular, with regards to controversial industries, while Dhar, Sarkar, and Ayittey (Reference Dhar, Sarkar and Ayittey2022) have noted the positive correlation between sustainability reporting and the sustainable development path of relevant companies.

Mathobela's (Reference Mathobela2010) interpretative research has indicated five challenges that may affect the coordination of sustainability reporting mechanisms: (i) stakeholder engagement, part of ‘stakeholder symbiosis’ and ‘dialogue[s] with each community of interest’; (ii) culture creation, which according to Schein (Reference Schein1993) promotes the acknowledgement and understanding of shared values; (iii) organisational learning; (iv) holistic thinking, entailing an awareness that complexity, integration and connectivity hinder leaders from applying simple top-down strategic models; and (v) measurement and reporting, involving the increasing number of standard and monitoring systems that should fit the particular culture of a firm (Latif, Cukier, Gagnon, & Chraibi, Reference Latif, Cukier, Gagnon and Chraibi2018). Moreover, accordingly with Kamble, Gunasekaran, and Gawankar (Reference Kamble, Gunasekaran and Gawankar2018), the effectiveness of industry 4.0 technologies in the promotion of efficiency and better organization of resources at SC level has been pointed out; therefore leading to a better coordination of activities overall also at firm level. Within the F&B sector, the coordination factor can also be influenced by sourcing standards, stakeholders' involvement in environmental impacts and the costs related to their engagement (Stranieri et al., Reference Stranieri, Orsi, Banterle and Ricci2019).

D'Souza, McCormack, Taghian, Chu, Sullivan-Mort, and Ahmed (Reference D'Souza, McCormack, Taghian, Chu, Sullivan-Mort and Ahmed2019) focus on sustainability's hard and soft competencies, outlining how they should be part of the education and organisational system. According to their qualitative literature analyses, these are as follows: (i) system thinking (Garrett & Roberson, Reference Garrett and Roberson2008); (ii) anticipatory competence; (iii) normative competence (Wiek, Withycombe, & Redman, Reference Wiek, Withycombe and Redman2011); (iv) strategic competence (Bryant & Jaworski, Reference Bryant and Jaworski2012; Loorbach, Reference Loorbach2007); (v) interpersonal competence (Wiek, Withycombe, & Redman, Reference Wiek, Withycombe and Redman2011); (vi) long-term, far-sighted reasoning and strategising (Pepper & Wildy, Reference Pepper and Wildy2008); (vii) stakeholder engagement and group collaboration (Segalàs, Ferrer-Balas, & Mulder, Reference Segalàs, Ferrer-Balas and Mulder2010); and (viii) action orientation and change agent skills (Wiek, Withycombe, & Redman, Reference Wiek, Withycombe and Redman2011). Bryant and Jaworski (Reference Bryant and Jaworski2012) have also identified gaps in certain skills and skill shortages specific to the F&B sector, highlighting the narrow segmentation of salient competences. For small workforce organisations such as SMEs, this problem might have even more impactful effects.

In addition, there is a vast literature supporting the role of stakeholder engagement in sustainability reporting; it has been validated as a valuable mechanism for effectively implementing standards (Braun, Visentin, da Silva Trentin, & Thomé, Reference Braun, Visentin, da Silva Trentin and Thomé2021) and enhancing organisational knowledge (Li, Zhu, & Darbandi, Reference Li, Zhu and Darbandi2022; Salvador, Barros, do Prado, Pagani, Piekarski, & de Francisco, Reference Salvador, Barros, do Prado, Pagani, Piekarski and de Francisco2021). Stakeholder voices, expectations and needs have a crucial role in defining the sustainability actions and communication process of a company, in achieving a sustainable competitive advantage (Waheed & Zhang, Reference Waheed and Zhang2020) and higher performance (Waheed & Yang, Reference Waheed and Yang2019). In particular, for SMEs, stakeholder expectations increase the pressure on corporate sustainability performance and demonstrate that social proximity is a motivation driver (Ernst, Gerken, Hack, & Hülsbeck, Reference Ernst, Gerken, Hack and Hülsbeck2022). In addition, D'Adamo (Reference D’adamo2022) further highlighted how stakeholder engagement in the Italian F&B context has further fostered: the impact on communities, innovation and product development, the commitment to the environmental dimension and local SC.

Internal and external corporate factors

Several authors have defined the relevant factors of sustainability reporting at the company level: the relevant determinants (Dienes, Sassen, & Fischer, Reference Dienes, Sassen and Fischer2016; Hahn & Kühnen, Reference Hahn and Kühnen2013), the relation between external and internal motives (Pérez-López, Moreno-Romero, & Barkemeyer, Reference Pérez-López, Moreno-Romero and Barkemeyer2015), the implementation of sustainability strategies (Crous, Battisti, & Leonidou, Reference Crous, Battisti and Leonidou2021) and the role of a progressive inclusion of sustainability principles in firms' strategic orientations and reporting practices (Melissen, Mzembe, Idemudia, & Novakovic, Reference Melissen, Mzembe, Idemudia and Novakovic2018).

Hahn and Kühnen (Reference Hahn and Kühnen2013) list corporate size and financial performance as the most frequently examined internal determinants of sustainability reporting and media exposure as the most frequently examined external determinants thereof. Since public reputation has been correlated with internal voluntary engagement and the avoidance of undesired behaviour (Lin-Hi & Blumberg, Reference Lin-Hi and Blumberg2018), it is one of the elements included in the overall evaluation of the evolution of sustainability orientation (see Table 1 for other references). Following Vitolla, Raimo, and Rubino (Reference Vitolla, Raimo and Rubino2019), this study therefore explores the relationship between integrated reporting and integrated thinking in the specific context of SMEs' black boxes, fostering an understanding of stakeholders' expectations of sustainability performance.

Pérez-López, Moreno-Romero, and Barkemeyer (Reference Pérez-López, Moreno-Romero and Barkemeyer2015) focus on the internal and external motives in corporate approaches to sustainability reporting. Such external motives include demonstrating compliance with local regulations and public norms, providing transparency to a range of stakeholders, garnering reputational benefits and credibility, ensuring the ability to communicate efforts, possessing the licence to operate and campaign. These motives reinforce the factors deemed relevant from the institutional perspective. On the other hand, the internal motives comprise environmental scanning, the improvement of risk management and the identification of strategic opportunities to enforce strategy formulation, evaluation and implementation. Other internal areas are, reasonably, operational performance-enhancing processes and cross-functional collaborations, the greater awareness of sustainability throughout an organisation, the enhanced ability to track progress towards specific targets and the innovation and learning process. According to Matten and Moon (Reference Matten and Moon2008), the planning of long-term sustainability initiatives seems predominantly associated with large firms in the European context due to the barriers that smaller firms face.

Risk (management) mitigation factors have been investigated mainly with a focus on the environmental dimension, e.g., by Kouloukoui et al. (Reference Kouloukoui, Sant'Anna, da Silva Gomes, de Oliveira Marinho, de Jong, Kiperstok and Torres2019) in relation to climate change. However, this challenge may not be perceived as sufficiently relevant, as an internal driver for polluting firms to implement more sustainable practices. In this context, especially in developing countries, institutional regulation has been suggested as an effective solution that anticipates social pressure, improves reputation and maintains legitimacy (Bridge, Reference Bridge2016). Firms' involvement with the environmental dimension is also associated with the adequacy and reliability of the measures and metrics they adopt (Helfaya & Whittington, Reference Helfaya and Whittington2019). For SMEs with more limited financial and human resources, then, this implementation is arguably more difficult, e.g., in the F&B sector.

However, a reliable performance measurement system is also a precondition for the development of effective strategy formulation at the firm level from the (talking to walk) and t(w)alking perspective of Schoeneborn, Morsing, and Crane (Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020). Similarly, other scholars have offered both empirical and theoretical evidence for the relevance of strategy formulation for the effective implementation of sustainability practices and communication (Manninen & Huiskonen, Reference Manninen and Huiskonen2022; Pizzi, Rosati, & Venturelli, Reference Pizzi, Rosati and Venturelli2021). Hence, among F&B SMEs, this process should foster a more reliable allocation of (limited) resources, disclosure of sustainability performance and higher motivation to transition to more sustainable managerial practices.

Methodology

This research adopts a qualitative interpretivist approach, which is particularly useful when the goal is to examine contemporary events and sets of relationships (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007; Landrum & Ohsowski, Reference Landrum and Ohsowski2018). This study is based on both primary and secondary data sources, consisting of semistructured interviews with CSR/sustainability managers/specialists, websites and companies' SRs, to allow the triangulation of data (Robertson & Samy, Reference Robertson and Samy2015).

The focal companies were selected from those in the statistical classification of economic activities (NACE rev. 2) in the manufacturing section (C), division of the ‘manufacture of food products’ (division 10), among the group involved in the ‘processing and preserving of meat and production of meat products’ (group 10.1). In the Italian context, 3632 companies were found in the AIDA – Bureau van Dijk database. Second, within this group, those with an active legal status were filtered (2315). Once the list was obtained, research on SRs was conducted using the ASSICA, the Italian association of meat and meat-based transformation products. Eight companies were identified as those that had implemented an SR, and four of them agreed to participate in the interviews (response rate 50%). To create an antagonist group that had not implemented formalised communication activities (SRs) but still had performed substantial sustainability-related actions, we filtered these companies by size, revenue, geographic area and business portfolio, whereby we identified six companies similar to the four companies we had already interviewed. Four of these six agreed to participate (75%). The total number of interviews (8–4 with sustainability actions and reporting practices, 4 with only sustainability actions and no reporting) was thus limited by the number of companies in the industry that produce SRs and the response rate we obtained, although it was very high (see Table 2 for company details).

Table 2. Sample characteristics

ISF, International Food Standard; BRC, British Retail Consortium; EMAS, Eco-Management and Audit Scheme; GMO, Genetically Modified Organisms.

The collected and analysed data came primarily from semistructured interviews (Farooq, Zaman, & Nadeem, Reference Farooq, Zaman and Nadeem2021; Kumar, Connell, & Bhattacharyya, Reference Kumar, Connell and Bhattacharyya2020; Roy, Al-Abdin, & Quazi, Reference Roy, Al-Abdin and Quazi2020) and secondarily, to supplement and deepen these, from the SRs of the companies producing them, their websites and other formal documents pertaining to sustainability. These secondary data were all discussed and used to offer important insights during the interviews and for complete and clear triangulation. The choice of the interview method was based on the fact that it is widely recognised as an appropriate and correct research method in studies concerning complex situations that cannot be analysed through quantitative methods, where direct contact and dialogue with the people involved in strategic choices are considered significant and relevant (Yin, Reference Yin2017). The choice, in particular, of the semistructured interview method was based on the desire to allow the opportunity, albeit controlled and limited, for the interviewees to add details or deviate from the questions asked when the interview protocol did not provide for any in-depth explanation of the concepts, facts and events deemed significant by the interviewees. This aspect is of particular importance in research on SMEs because of the differences, even substantial ones, which distinguish them from other types of businesses. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to leave room for respondents' further reflections. The methodological and operational guide for the preparation and execution of the interviews followed the interview protocol, created using previous research and carefully adapted to the focal industry. It was constructed to analyse the different institutional and firm-level factors that could play a role (of any kind) in the relationship between sustainability actions and sustainability reporting. Supplementary Table I thus illustrates how the interview protocol was structured and the questions that were proposed in the interviews. To confirm the validity, clarity and effectiveness of the protocol, it was successfully tested on a company outside the sample but within the same industry sector.

All the interviews were conducted through online video conference platforms from February 2022 to September 2022, and two members of the research team were involved in all of them, which ranged from 45 min to 1.5 h. All audio that was recorded (with the consent of the participants) was transcribed and analysed by the whole research team with the help of NVivo software.

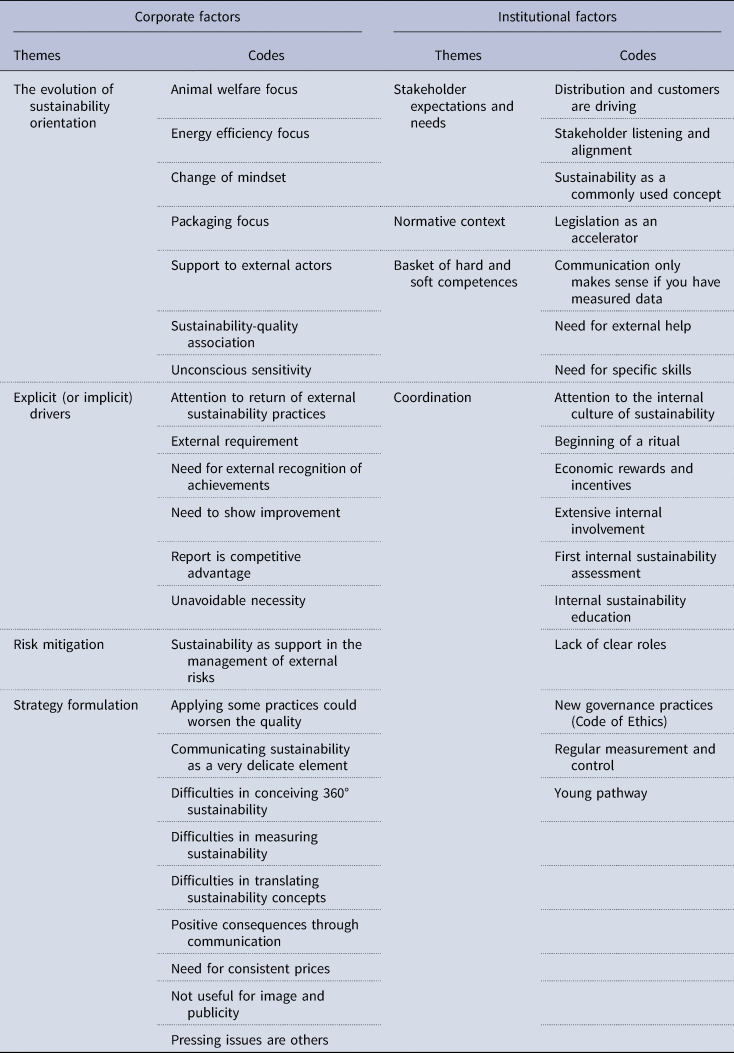

We conducted thematic analysis to deepen the patterns within the data collected through the interviews (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). This is a useful and validated qualitative method for identifying, analysing, organising, describing and reporting the themes found in a variety of data (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, Reference Nowell, Norris, White and Moules2017). In particular, it allows researchers to highlight similarities and differences and to generate novel insights or summarise key issues. The first step in thematic analysis is data familiarisation across the research team that has interpreted the main, emerging issues from data coding (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, Reference Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill2016). In the second step, the data were coded by the three authors to highlight all the relevant content. All the codes were then reviewed by the entire research team. Each term, sentence or paragraph relevant to the research, according to the adopted theoretical-conceptual framework and the objectives of the analysis, was coded by categorising it according to an underlying significant element (a total of 40 codes were created). In this step, the significant content collected through the interviews was organised and structured to ensure a comprehensive analysis, capable of showing the elements of distinctiveness among the focal companies. The third step was the organisation and subdivision of the codes obtained from the analysis of the interviews into different main themes. This step in the empirical analysis was carried out through careful textual analysis by the entire research team, which made it possible to group all the significant codes into the eight identified themes (see Table 3). The specific meaning of the codes assigned to each theme suggests how the latter is present within the researched sample, delineating the role of the selected factors in constructing the relationship between actions and sustainability reporting and allowing a deeper exploration and understanding of the peculiarities of SMEs, as described in the following section.

Table 3. Themes and codes

Discussion of findings

The coding activity that resulted from the application of the factors proposed in the literature in this study made it possible to highlight the significant trends among the focal SMEs and to shed light on important differences between companies that adopt substantial sustainability practices without any socioenvironmental reporting and companies that engage in both substantial action and reporting processes (see Table 4 for the results overview). Accordingly, our analysis and presentation of the predominant factors, their role in sustainability action and reporting, and the differences between the two groups of focal SMEs have allowed us to deepen the understanding of the singular and distinct processes among SMEs and to significantly extend the explanation of the mechanisms linking sustainability action and communication processes.

Table 4. Results overview

The evolution of sustainability orientation

The sustainability orientation of the focal companies, especially in light of the particular industrial sector where they operate (meat and cured meats) and the country in which they are based (Italy), represents the first relevant factor to be analysed, given, moreover, their increasingly consistent push towards sustainability practices (and their communication) by regulators and different groups of stakeholders. For both groups of companies, reporting companies (RCs) and silent companies (SCs), the sensitivity to the macrotheme of sustainability is always present (100% of the companies surveyed). This consideration of the topic is, however, something unconscious and not formalised or according to a specific historical moment in or evolutionary step of a company. It is, therefore, a topic that according to the interviewees has always been present in the sensitivity of company managers or owners. For example, as one interviewee claimed, ‘What I can say confidently is that the approach to sustainability has always been there’ (SC3). Another one stated that ‘…even if unconsciously, there was a particular attention, even from our president who was the 100 percent owner of the company before the end of 2019…’ (RC1). This presence, although not formalised, has inevitably led this company to adopt certain sustainability practices, to set its socioenvironmental improvement objectives and, in some cases, to create forms for reporting and communicating the results achieved (see RCs).

In the projections towards more sustainable processes and strategies, however, among 50% of the focal SMEs (half RCs and half SCs), there is an ambiguous conceptual relationship between the very concept of sustainability and that of quality (of the end product). The sustainability–quality relationship is seen by half the sample as something natural and inseparable, as if the attention to sustainability practices automatically leads to an increase in the quality of the end product and vice versa. This relationship is seen as fundamental and necessary; hence, ‘We pursue a path of sustainability that must respect the quality of our product; otherwise, we would betray our consumers. It has to be a fair mediation, that is, pursuing a sustainable path while maintaining the cornerstones of our product’ (RC2).

Despite the clear focus on and consideration of sustainability among both groups of SMEs, there is a substantial difference between the RCs and SCs: the change in mindset underlying the adoption of substantial sustainability practices. As RC4 highlighted, this is a new approach to producing and doing business, namely, ‘…an approach that is not the mere focus on how much the product costs; you start from certainly more important and higher values’. This is a change in the managerial vision specific to RCs (75% of RCs and 0% of SCs) and characterised, primarily, by ‘a new openness, also mentally’ (RC1). The openness mentioned in this RC has probably led to a felt need and a strong desire to be open to the outside world, rendered explicit, operationally, through the measurement of its socio-environmental performance and its subsequent reporting. In other cases (SCs), the lack of sustainability reporting is linked to a lack of any change in approach to business management. The RCs that mentioned this new approach emphasised that the practice of reporting, to corporate stakeholders, one's sustainability practices and goals is a final step in the change process. It is a tool for communicating what has been done and what will be done, the so-called walking to talk formative view analysed and proposed by Schoeneborn, Morsing, and Crane (Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020). This approach is also in line with Dhar, Sarkar, and Ayittey (Reference Dhar, Sarkar and Ayittey2022), who highlight an important connection between sustainability communication/reporting and the path of a company towards more sustainable management and impact. These represent two sides of the same coin that are difficult to separate, and for which it is difficult to establish a logical-temporal sequence, as they are often interconnected and self-feeding processes.

Specifically, the general evolution towards more sustainable approaches has led both groups of SMEs, with very few differences, to focus their attention on a particular group of sensitive issues in their sector (in decreasing order of importance): energy efficiency (88% of the total), animal welfare (63% of the total), support for external stakeholders (50% of the total) and packaging (25% of the total). These are the issues that have not only been felt and addressed by most of the focal SMEs (as far as energy efficiency and animal welfare are concerned) but are also due to recent crises that have enabled a strong push towards maximum energy efficiency and the use of renewable energy sources. For example, ‘we have a considerable area of photovoltaic panels and have already planned a major implementation…We are also trying in every way to implement biogas’ (SC3). In addition, the demands of the market and key stakeholders (in this case, the distribution tier of the SC) have provided a further element for acceleration, especially towards enhanced animal welfare and animal rights, as clearly recalled by SC3: ‘there's really a discussion of the animal welfare approach as far as the whole supply chain is concerned…it's something that's in our DNA’.

Explicit (or implicit) drivers

Seventy-five per cent of the focal SMEs clearly stated that attention to sustainability (regardless of the focus on communication or substantive action) has become an inescapable necessity and a strong external requirement. ‘Today, moving towards a path of sustainability is a necessity’, stated SC1, something taken up and reinforced by RC3: ‘We do it, yes, for an ethical reason, but now, it is no longer just an ethical reason. Here is the world that is changing and going in this direction.’ In short, this is an issue that cannot be avoided, even for these SMEs in a sector that is inextricably rooted in national and local traditions and culture. Indeed, the theme of this unavoidable need is the concept most repeated and expressed throughout the research, especially by the group of RCs (100 vs. 50% of SCs). The understanding of this necessity is closely linked to the demand and needs of their stakeholders and the society with which these SMEs relate, as stated by RC4: ‘I have tried to be forward-looking, and I have realised that this is a forced path.’

Despite this broad recognition, some drivers play a key role only in the RC group, entailing an absence from SCs and a 75% presence among RCs. These drivers are the need for external recognition of achievements (in sustainability), the need to show improvement (in sustainability) and the use of sustainability reporting as a source of competitive advantage. These are three elements inherent to the openness of one's practices and behaviour to the outside world, a strong link to the concept of transparency. Although RCs maintain active, positive sustainability processes and practices, they do not contemplate the need to communicate these achievements and commitments externally, as they do not see this as a possible source of competitive advantage. In this logic, RCs see the potential of this transparency and the potential consequent benefits and feel the need to ‘…to improve and close the gaps more and more by then providing objective data and showing this continuous improvement, and more and more we are going to communicate it accordingly’ (RC1). This is clearly a formative t(w)alking perspective (Schoeneborn, Morsing, & Crane, Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020) where sustainability actions go hand in hand with sustainability reporting in a mutually supportive and self-sustaining process (Dhar, Sarkar, & Ayittey, Reference Dhar, Sarkar and Ayittey2022). The reporting process for these RCs, then, is only one step in a broader process of measurement and improvement; in fact, ‘the main purpose is to measure goal achievement. To measure what I did, whether I did it and how I did it, and to give myself additional goals. So, here, then, is the evolution: to determine how you see yourself in future years and decide what action to take’ (RC4). The approach driving SCs, on the other hand, is totally different, almost antipodal. It is a process that entails the adoption of sustainability practices with a strong component based on the search for economic return (an element present in 100% of CSs vs. 0% of RCs) but that avoids reporting practices via a perspective clearly aligned with ‘greenhushing’, i.e., the deliberate choice to omit or only partially provide information on one's effective sustainability practices to avoid creating problems for one's own sector, collaborating companies or clients (Font, Elgammal, & Lamond, Reference Font, Elgammal and Lamond2017).

Risk mitigation

A third theme considered relevant by the focal sample, albeit only RCs (50% of them vs. 0% of SCs), is the consideration and adoption of substantial sustainability practices, as well as communication for risk management and mitigation. Indeed, the data analysis indicated that it is fundamental to consider ‘the risk that we can have overnight for our economic activities. These risks are linked to sustainability because, for example, intensive and hyperintensive livestock farms are at a very high risk for the spread of various diseases, and so we understand that it is all linked and that these are clearly risks that should not be underestimated’ (RC1). The RCs also evaluated this link between sustainability actions and the better management of business or contingent risks. This constitutes a further awareness of the potential benefits of adopting a sustainable approach and its links with other areas of business management, as well as with additional internal and external strategic elements.

Strategy formulation

Concerning sustainability actions and their reporting, several critical and weak elements emerged strongly and significantly from the data analysis and were widespread among the various focal SMEs. These elements are indifferently present among both RCs and SCs. The first aspect concerns the negative potential of the application of certain sustainability actions (especially the most impacting and complex ones) on the quality of a product and thus on the company's ability to continue to maintain the production processes and quality of raw materials thereof, as clearly explained by RC2: ‘today, the company would not be ready to apply these practices, mostly because the quality of our product would be affected’. This goes hand in hand with reinforcing a feeling of uncertainty amid action towards sustainability with the knowledge, or at least the perception, that the current pressing issues to be addressed are others, such as those ‘related to the energy market and the availability of raw materials’ (RC1). This limiting force is added to the concrete and operational difficulties that SMEs in the Italian meat and charcuterie sector face today with regards to sustainability, namely, (1) the complexities when translating concepts linked to the socioenvironmental sphere into concrete actions and projects (50% of total SMEs) and (2) the strategic and operational difficulty in measuring progress in the field of sustainability (also 50% of total SMEs). These two problems in the narratives and the words of the interviewees are thus strongly connected and linked to strategic, operational and management difficulties. That is, these practices are mostly new and have not yet been appropriately and stably embedded within corporate systems: ‘We have not yet started a real measurement path. A new preliminary activity has been done, but only the real assessment activity will lead us to understand what our real needs are…at present I honestly don't know because we don't have experience in this regard…I don't know whether it will be sufficient to have a coordinating person to collect the various information from the different functions or whether it will also be necessary, from a future perspective, to structure properly’ (SC2). A further difficulty concerns only SCs: contemplating sustainability at 360°, i.e., applying it in all areas of one's own business life and all ongoing processes. This limitation has been perceived, above all, in relation to any potential consequences, including for the product and market levels, e.g., ‘if you want to do a broad sustainability project starting from farming to the last stages, it means making a product that is probably for a niche market’ (SC4). When the strategic aspect is shifted to the issue of communication and reporting (already current – RCs – or potential in the future – SCs), the focal elements show that there is a strong and positive perception (75% of RCs) of communication/reporting, which is seen by RCs as a tool for obtaining further advantages and positive consequences (in terms of the market, relations, images, regulations), and not only as the last step towards sustainable action. These positive aspects, however, are seen by RCs as connected to a still unresolved factor, namely, the lack of recognition by consumers of a more sustainable product or one produced by a more sustainable company (100% RCs), e.g., ‘in Italy, so many people talk about it (sustainability), but when you are confronted with the different costs of a sustainable company's products, then you immediately stop. We feel sadness because everyone talks about it, everyone wants sustainable products, but then no one pays for them. In contrast, abroad, the sensibility is different’ (RC3). On the other hand, aspects that are coordinated between the two groups of SMEs and of extreme importance concern low usefulness, for image purposes in the focal sector, of sustainability communication compared to other strategic tools (63% of all SMEs) and the sensitivity of communicating sustainability aspects to the public and the market (63% of all SMEs): ‘Sustainability reporting in our industry has been used discreetly, carefully and accurately, but little, from a publicity standpoint, because that was not the goal’ (SC2). Disclosing one's brand, vision and products is not, for the majority of companies, considered an aspect directly connected with sustainability reporting to which other objectives are linked. Even the objective of the transparency and exchange of information with various stakeholders is not perpetuated by sustainability reporting, e.g., ‘many clients do not go to check our sustainability report but ask us for very specific information’ (RC3). There is also much resistance to the use and publication of sustainability reporting documents (e.g., SRs) because ‘the fact that we are increasing sustainability communication and emphasise certain issues related to sustainability is quite a delicate thing’ (RC1). This is also the case for those who are not currently reporting, the SCs, but are reflecting on the possibility of doing so, such as SC4, who claims that the first SR his or her firm is about to produce will be ‘for internal use; it will not yet be made public’. From the analysis on strategy formulation factors, it has thus emerged how the approach adopted by the focal SMEs for sustainability action and reporting is always of a formative nature. These actions lead to the construction of communication, which in turn plays a clear role in self-improvement (walking to talk) (Schoeneborn, Morsing, & Crane, Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020) that can be contaminated by a perspective linked to ‘greenhushing’, above all, for reasons driven by the fear of triggering negative processes on the market and exposing one's company to criticism or misunderstanding (Font, Elgammal, & Lamond, Reference Font, Elgammal and Lamond2017).

Stakeholder expectations and needs

With regards to attention to and openness towards stakeholders internal and external, there is a clear difference between SCs and RCs (0% for SCs vs. 50% for RCs). The latter have a stronger propensity to listen to stakeholders and align with their requests and wishes. RC3 effectively defined this process in relation to the definition of sustainability goals: ‘We did, with all our stakeholders, an assessment in which we interviewed customers, suppliers, associations, [and] banks, asking what they consider important values to carry forward in our sustainable development. We then cross-referenced our strategic sustainability plan with the same assessment in such a way that we redefined a strategic sustainability plan, influenced by our stakeholders, and [then,] based on that, we defined the activities that we are going to do in the medium term.’ In this virtuous process, the RCs themselves have noted that a supportive element in addressing different stakeholder groups is that sustainability today ‘represents a common language’ (RC1). Additionally, in this case, a clear dynamic has emerged that can be attributed to the category of t(w)alking. The process of communicating, or even just the willingness to communicate, pushes a company to work harder to achieve results regarding the sustainability of its processes and impacts. In this case, listening to and considering stakeholders is enhanced when a company is committed to communicating its sustainability practices and achievements (Schoeneborn, Morsing, & Crane, Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020).

A common characteristic among the RCs and SCs is the identification of distribution customers and consumers as the key stakeholders, capable of drawing the line to be followed and of influencing important strategic decisions and the future (present for 88% of the total focal SMEs). These two stakeholder groups in the focal sector are steadily increasing their level of attention to and interest in sustainability issues, thereby driving companies towards increasingly sustainable practices: ‘Consumers, at least according to what they say, are increasingly aware of sustainability issues, but so are our customers (distribution)’ (SC4).

Normative context

In 63% of the cases, with no relevant differences between SCs and RCs, national and international legislation and regulation is seen as a tool for accelerating sustainability actions and sustainability reporting. A large proportion of the focal SMEs also recognise the existence of a potential risk in failing to proactively adapt to sustainability legislation, for example, ‘the real problem is that in two/three years the carbon footprint will probably be mandatory and will have to be included in the sustainability reporting … if we don't do it this year, probably, in two or three years it will be mandatory, so you need to be able to be one step ahead of the others’ (RC3). This path is also seen as positive due to another aspect, namely, its potential cascading effects on the entire SC, which today cannot yet be measured to report and disseminate meaningful and complete data on these nonfinancial impacts. In fact, for SC4, ‘pushing even the smallest companies to have simple tools for monitoring sustainability performance would allow access to information and its visibility in our supply chain because if we go, today, and ask our SMEs to tell us some sustainability performance data that is environmental and social, it is likely that they will have nothing to tell us’. In this case, then, legislation, if focused on supporting/encouraging/obliging sustainability communication (as is the case in Europe today), can play a role in creating the formative relationship between actions and communication. Moreover, a company pushed or obliged to report its sustainability practices will inevitably, and with distinct timing and motivations, be pushed to adopt certain sustainable practices.

Basket of hard and soft competences

In the field of skills, there is substantial agreement among the RCs and the SCs: the awareness of the importance of measuring data prior to their communication. However, there is also a need to find the specific skills for carrying out these processes; sometimes, these skills can only be found by relying on external help and professionalism. Among 75% of the focal SMEs (100% for RCs and 50% for SCs), the precise and structured measurement of socioenvironmental data/performances is considered fundamental for communicating results and progress externally, which is more in line with a representative vision of the relationship between sustainability actions and sustainability reporting (walking to talk according to Schoeneborn, Morsing, and Crane, Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020). The systematised process of collecting data and analysing and interpreting them is thus a fundamental basis for all subsequent processes of utilisation in operational strategies and concrete practices, as well as in communicative actions, as advocated by RC1: ‘if you have measured sustainability issues, then you are clearly in a precise position, and you can communicate them, otherwise it becomes, like, overgeneralised and overblown communication, related to sustainability’. Here, the representative approach is demonstrated by extending the competence factor, highlighting how transversal skills regarding sustainable transition are of vital importance and have a joint effect, first, on effective change and, second, as a direct consequence for communication skills. RC4 emphasised this as follows: ‘sustainability must become truly tangible and not just stop at words’. Accordingly, communication practices that are not based on concrete and correctly measured data, such as greenwashing, are recognised as incorrect and inappropriate. Among 75% of the focal SMEs, there is a clear perception of the need for external professional support, both for substantive practices and for the communication aspect, e.g., the practice of ‘using outside consultants to prepare the sustainability report’ (RC3). Even when these skills are not sought externally (in 88% of SMEs), it is necessary to have specialised skills and ‘someone with a more open mind who can enable us to derive the sustainability data and analyse them’ (RC3).

Coordination

Finally, with regards to coordination within the focal SMEs for sustainability actions and communication, there is a strong focus on internal culture concerning sustainability issues (63% of the total), on education in these issues (75% of the total) and on the creation, in some cases, of new and sustainable governance tools, such as a code of ethics (38% of the total). On the other hand, in 63% of the cases, sustainability practices represent, with all the problems of each case, a new path for these companies, whereby 50% of these cases lack clearly identified roles within their corporate governance. The aspect internal culture is also strongly felt; hence, it was defined by SC2 as ‘a substrate of culture that needs to be brought into the company and that needs to be across the board. If this is not there, it becomes very difficult, then, to move projects forward. The risk is to create situations that are understood only in one office and are not then shared by the whole company’. This optimal condition becomes attainable if one invests and believes in the specific education of the people who make up and work in one's company. Accordingly, in most of the focal SMEs, actions and strategies are planned to ensure the ‘continuous training of employees’ (RC3). Regardless of the focal group (RCs or SCs), however, in more than half the cases, these paths and choices were adopted a few years ago, especially from 2019 onwards. The newness of this change has thus inevitably entailed the difficulty of insufficient organisation and preparation, made even more evident in the context of the SCs. In fact, as specified by RC1, these have often been situations in which ‘each one doesn't have a very specific function; we do a lot of different things. So, anyway it was a quite invasive process’. This path, exclusively for RCs, has in 50% of these cases marked the beginning of a veritably new operational and procedural ritual; for all the RCs, this has meant the broad involvement of several corporate areas. This ritual specifically refers to the inclusion, in the succession of activities, actions related to strategic planning, measurement, reporting and monitoring in terms of sustainability: ‘a ritual where at least once in a year, in the sustainability report, you have to be measured and take stock of and look at improvements from all angles’ (RC1) with the goal of ‘monitoring the state of the art with respect to the different priority areas on sustainability, just for the sustainability report that we are now building’ (RC2). It is clear, then, how this consideration of measuring and monitoring social-environmental performance leads to the formative talking to walk vision, where the willingness to communicate to the best of one's ability provides input and impetus to substantive sustainability practices (Schoeneborn, Morsing, & Crane, Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020). The SR therefore becomes a ‘tool for keeping the bar straight. Each year, within the sustainability report, we take a snapshot of how we are positioned on the various areas and set goals for the following years’ (RC3). To support and enhance this tool and its potential positive effects across their entire company, 75% of the RCs have adopted economic incentive systems based on sustainability targets, which entail ‘tying sustainability goals to corporate rewards, and, as a result, those involved in this system always want to know the degree of the achievement of the goals and the current performance because, in addition to being involved from a moral point of view, they are also involved from an economic point of view’ (RC2).

Conclusions, implications and future research directions

Analysing the link between sustainability actions and sustainability reporting is of particular relevance, especially in the field of SMEs, given their peculiarities compared to large companies, the typical subjects of SR studies. Taking the different approaches to sustainability reporting outlined by Schoeneborn, Morsing, and Crane (Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020) as the conceptual foundations and focusing on a framework of sustainability factors derived from the literature (referring to institutional and corporate factors), the substantive and communicative practices of four communicating and four noncommunicating SMEs in the Italian meat and cured meat industry have been analysed. A qualitative interpretative approach with a mixed deductive-inductive method has enabled, through a semistructured interview protocol and analysis of other secondary data, adapting and contextualising extant results concerning SMEs, which to date remain rather underinvestigated (Álvarez Jaramillo, Zartha Sossa, & Orozco Mendoza, Reference Álvarez Jaramillo, Zartha Sossa and Orozco Mendoza2019; Bos-Brouwers, Reference Bos-Brouwers2010; Cassells & Lewis, Reference Cassells and Lewis2011; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2004a). Through a thematic analysis of the collected data, the concepts that have emerged from the focal SCs and RCs and the factors that could create differences between these two groups have been disclosed. Focus was placed on sustainability communication practices, substantive sustainability practices and their relationships.

The first finding therefore advances knowledge regarding the factors that may limit or accelerate substantive and/or communication practices with regards to sustainability. In the previous section, it was noted that the various topics explored have different effects on the practices of the focal SMEs. In sum, with regards to the institutional factor of corporate evolution towards sustainability, the progress of the focal companies towards a greater consideration of sustainability in their practices has created a strong conviction for a concrete commitment to and creation of sustainability actions, which can subsequently be reported and narrated in specific communication (SR). This is the formative walking to talk perspective (Schoeneborn, Morsing, & Crane, Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020), where the reporting process also plays a role in operational practices: it is not just a recounting of the past but a steppingstone from which to start again and, thus, both a spur to do better and a direction for the future. This view is also reinforced by a company-level factor, the skills needed. These skills play a key role in ensuring that the link between actions and sustainability reporting is not just representative but formative, i.e., based on real and properly measured data. The factor represented by implicit and explicit drivers (Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2008; Pérez-López, Moreno-Romero, & Barkemeyer, Reference Pérez-López, Moreno-Romero and Barkemeyer2015; see Table 1) also leads to a greater integration of sustainability actions and sustainability reporting, whereby we can consider their link as t(w)alking, i.e., a formative vision in which reporting and action go hand in hand, feeding off each other and continuously reinforcing each other. Additionally, regarding the strategic factor, the validity for the focal SMEs of this perspective and this link has been highlighted (Manninen & Huiskonen, Reference Manninen and Huiskonen2022; Pizzi, Reference Pizzi2018; see Table 1). In this case, however, the communication carried out is deliberately limited or even absent due to a clear and precise will of company management (so-called greenhushing) (see Font, Elgammal, & Lamond, Reference Font, Elgammal and Lamond2017). In the focal industry, in fact, there are particular dynamics worthy of further investigation, for which the communication of positive sustainability practices could paradoxically create negative effects with repercussions for a company and its relations with other market players. This represents a possible limiting and blocking factor, together with the rather widespread lack of specialised expertise and the difficulty of putting sustainability concepts into practice, especially in regards to systematic measurement practices. Some elements, however, can function as potential resolvers, such as relevant legislation, the demands of key stakeholders and the changing mentalities in the market and within companies.

The second contribution has a theoretical-conceptual nature. This study has applied the framework of Schoeneborn, Morsing, and Crane (Reference Schoeneborn, Morsing and Crane2020) to the sphere of SMEs and verified its validity and practical applicability. Hence, there is a strong and evident need to identify the theoretical-conceptual bases that are also valid for the business fabric of SMEs, thus far insufficiently considered or analysed with unsuitable theoretical frameworks or conceptual bases.

The third contribution concerns the disclosure of the effective practices in the focal field, carried out by SMEs, and of some weaknesses yet to be resolved. Thus, this study has relevant managerial implications for SMEs in different sectors engaged in sustainability communication actions and/or practices. The results highlighted above provide a broad view of the possible choices for the communication of sustainability performance and the relationship between substantive actions and formal communication. Despite the peculiarities of the focal sector, which have inevitably influenced the behaviour of the focal companies, the delicacy of communicative action, especially towards certain categories of stakeholders, is evident. Communication, then, is often seen only as a tool for improving economic and market performance, but it could also negatively influence relations with other actors in the SC without creating positive cascading effects. On the other hand, the results presented above clearly illustrate an overall picture, whereby companies approaching sustainability communication are more strongly pushed and urged to pay more attention to the substantive aspects as well, the so-called formative role of communication. This role should not be underestimated by companies that today do not communicate or do so without conviction; it is capable of triggering a virtuous circle from which the various aspects linked to economic returns, market competitiveness, relations with stakeholders and proactive actions towards changes and unforeseen events can certainly benefit. Consequently, the fourth contribution impacts the policies concerning the behaviour of companies in the field of sustainability and its communication. European regulations are shaping sustainability communication by periodically setting increasingly specific and challenging targets for companies through nonfinancial reporting directives. With the new Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD – 2022/2464/EU), an extremely impactful and relevant process is about to start, which will see listed SMEs obliged to produce a document able of reporting on aspects and impacts inherent to the social, environmental and governance spheres of companies from 1 January 2016 (with an impact on published reports from 2017). To support this change, companies (not only SMEs) will also have at their disposal a new set of reference standards valid throughout the European Union for nonfinancial reporting: European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) created by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG). This push by the European bodies will affect not only the number of companies (including SMEs) obliged to sustainability reporting (almost 50,000) but also their substantive practices and their relationship with related communication and transparency. In light of the above results, then, the formative and accelerating effect that the incentivisation or even compulsory nature of nonfinancial reporting can have on economic actors is evident, especially in sectors such as the one investigated, where social and/or environmental issues and impacts are relevant.

Nevertheless, this research, like all scientific research, has certain limitations. These are (1) the focus on a single industry (meat and cured meat) in a single country (Italy), (2) the lack of possibility for the generalisation of the results (qualitative study based on interviews) and (3) the limited number of companies included in the sample (due to the limited number, 8, of the companies in the panorama of contacted companies producing SRs).

Future research could thus verify the applicability of this study's theoretical framework, in particular, the validity of the two focal approaches (walking to talk and t(w)alking, as well as the practice of ‘greenhushing’) for SMEs in other industrial sectors. Studies could thereby expand the focal subject and employ different methods, such as those belonging to quantitative methodologies, to broaden the possibility of generalising the above results.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2023.40

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Doctoral School on the Agro-Food System (Agrisystem) of the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Italy).

Financial support

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore contributed to the funding of this research project and its publication (D.3.2. 2020 – R2104500099 – VIS – Valore Impresa Sostenibile).

Competing interests

None.

Davide Galli is an associate professor of Business Administration at the Faculty of Economics and Law, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Piacenza (Italy). He is a member of the Technical Commission for Performance, an advisory body of the Department of Public Administration whose task is to define the technical-methodological guidelines necessary for the development of performance measurement and assessment activities in public administrations. Over the years, he gained professional experience ranging from university research to management training, from management consulting to professional activities. Since 2011 at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Piacenza campus, he has been dealing with issues related to sustainability, corporate social responsibility and corporate performance analysis.

Riccardo Torelli is a research fellow in Business Sustainability and Ethics at the Faculty of Economics and Law (Department of Economic and Social Sciences) of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore (Piacenza – Italy). He is also an adjunct professor of Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Business Strategy. His research focuses on corporate sustainability and SDGs, CSR and business ethics, nonfinancial reporting and greenwashing. He is a member of Centre for Social and Environmental Accounting Research (CSEAR), European Business Ethics Network (EBEN) and Associate Editor of Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management and of Journal of Public Affairs. He has published several international contributions, in particular in Journal of Business Ethics, Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal, Business Strategy and the Environment, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Journal of Cleaner Production, Social Responsibility Journal and in some Springer edited books. He is a member of several interdisciplinary projects on business sustainability. He is also the co-founder and secretary of the Research Centre for Responsibility, Ethics and Sustainability in Management – RES.m HUB.

Andrea Caccialanza is a PhD candidate at Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Piacenza (Italy). His research covers topics such as sustainability reporting determinants in agrifood systems, food production systems and supply chains, SDGs and gender equality, sustainability and social impact in megaprojects. He is a member of the Center for Social and Environmental Accounting Research (CSEAR), the Italian Association for Management and Marketing studies (SIMA-SIM), the Italian society of accounting and business administration (SIDREA) and the European Business Ethics Network (EBEN). He is holding a position of exercises tutor of Integrated Reporting and Sustainable Value . He is a member of two interfaculty projects: the first focuses on sustainability performances of companies in the meat and cured meat industry, and the second on how climate change impacts several emerging risks in the agrifood chain. He is co-editor and co-author of a Springer edited book focused on meat and cured meat sustainable supply chain. He is also co-author of a review article on meat production sustainable supply chain practices published in the British Food Journal.