Introduction

An increasing proportion of children worldwide live with only one parent, typically their mother (Institute for Family Studies & Wheatley Institution, 2019; Liu, Esteve, & Treviño, Reference Liu, Esteve and Treviño2017). In most countries, a significant proportion of lone-mother families experience poverty (Maldonado & Nieuwenhuis, Reference Maldonado and Nieuwenhuis2015). One policy that has the potential to improve the economic well-being of these families is child support, a monetary transfer from a non-resident parent to a resident parent (the lone parent) to assist with the cost of raising children following union dissolution. Child support could significantly address the poverty of children in lone-parent families around the world, yet in many countries, we know relatively little about the types of child support policies in place and even less about their effectiveness.

The limited research that does exist has examined child support policy in high-income countries (for a recent review, see Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cuesta, Haapanen and Meyer2022). Very little is known about how middle- and low-income countries approach whether non-resident parents should provide child support, nor how much is expected, nor whether this is actually paid. We contribute to addressing this research gap by conducting the first cross-national comparison of child support policy in 37 middle- and low-income countries. We aim to answer three research questions: (1) How do these countries approach child support policy in terms of institutional arrangements, and procedures for determining child support amounts and enforcing obligations? (2) How much child support is received in these countries? and (3) What are the key dilemmas these countries face in their approach to child support policy?

To answer the first question, we use data obtained from a systematic review of literature written in English since 2010 to report on policies in all 35 middle- and low-income countries for which we found data. For the second question, we use the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database, the premier data source that has information on the income of individuals in many countries. We provide results on child support receipt in the nine middle- and low-income countries that have data on child support. In both the systematic review and the quantitative analysis, we compare our results to those of high-income countries when it is available. Our results along with published data on socioeconomic indicators and family trends inform our discussion about policy dilemmas faced by middle- and low-income countries in their approach to child support policy.

We use the 2021–2022 World Bank country classifications to identify low- and middle-income countries.Footnote 1 We include 37 countries for which we found information; these include countries in Africa (ie. Botswana, Egypt, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kingdom of Eswatini, Lesotho, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Tunisia, Zambia and Zimbabwe), Asia-Pacific (ie. Cambodia, China, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Russian Federation and Vietnam), Central and South America (eg. Brazil, Colombia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay and Peru), and Eastern Europe (ie. Georgia, Romania, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine). Among the 37 countries, we have data on policies in 35 countries and individual child support receipt in nine countries (in seven countries we have data on both). These 37 countries provide the first broad analysis of child support policy in middle- and low-income countries in the research literature.

Country contexts

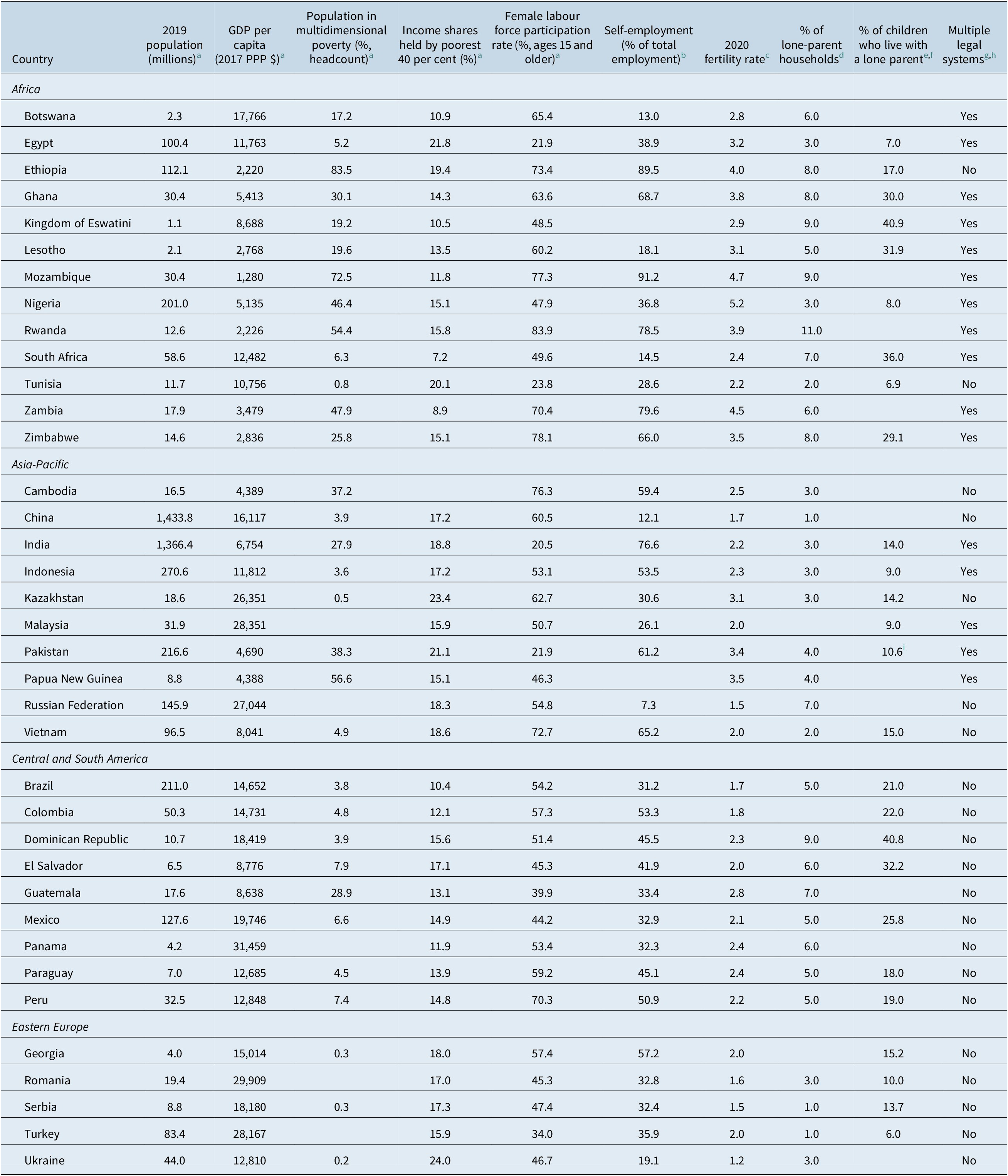

Child support policy may be influenced by a country’s economic resources; for example, if a substantial number of lone parents live below poverty, it may be especially important for children to receive this income source, but it may simultaneously be difficult for non-resident parents to pay. Another important factor could be the extent to which mothers are working, as mothers without other sources of income might be particularly dependent on the other parent to provide resources. Other economic, cultural, historical and demographic factors may also be important, including a country’s administrative capacity or the extent to which a country experienced colonization. Contextual information on the 37 countries is presented in Table 1. (Note that on some indicators we do not have information from all countries.) The countries vary substantially. Total population ranges from 1 million in the Kingdom of Eswatini to over 1 billion in China and India (United Nations Development Programme, 2022). Even though we have selected countries on the level of income, because we include both middle- and low-income countries, there is substantial variation in GDP per capita, with several countries over $25,000 PPP US$ (mostly in Europe and Asia), and some under $5,000 (mostly in Africa). Using a measure of multidimensional poverty, poverty rates also vary dramatically, from less than 1 per cent in Tunisia, Kazakhstan, Georgia, Serbia and Ukraine to over 70 per cent in Ethiopia and Mozambique (United Nations Development Programme, 2022). Income inequality is relatively high in most countries. In 32 of the 36 countries with data, the poorest 40 per cent holds less than 20 per cent of the national income, with the poorest 40 per cent in South Africa and Zambia holding less than 10 per cent (United Nations Development Programme, 2022). Labour participation of women aged 15 and older varies substantially, from 20.5 per cent in India to 83.9 per cent in Rwanda (United Nations Development Programme, 2022). Self-employment is common in most countries: in 27 of the 35 countries with data, more than 30 per cent of the employed population is self-employed (Elgin et al., Reference Elgin, Kose, Ohnsorge and Yu2021), and in some countries it is particularly high: in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Rwanda, Zambia and India at least 75 per cent of employment is self-generated. Fertility rates range from below replacement (which is about 2.1 children/woman) in 12 countries to 4.7 in Mozambique and 5.2 in Nigeria (World Bank, 2022a). The percentage of lone-parent households ranges from 1 per cent in China, Serbia and Turkey to 9 per cent or more in the Kingdom of Eswatini, Mozambique, Rwanda and the Dominican Republic (Pew Research Center, 2019). Among the 26 countries with available data, more than 30 per cent of children live with a lone parent in four (the Kingdom of Eswatini, Lesotho, South Africa and the Dominican Republic; Institute for Family Studies & Wheatley Institution, 2019; UNICEF, 2021). Finally, 16 of the 37 countries recognise multiple legal systems (CIA, 2021; Hauser Global Law School & New York University School of Law, 2021). These data show not only substantial differences across countries, but also some general differences from high-income countries, which will have implications for policy, discussed below.

Table 1. Contextual data of countries.

a United Nations Development Programme (2022).

b Elgin et al. (Reference Elgin, Kose, Ohnsorge and Yu2021).

c World Bank (2022a).

d Pew Research Center (2019).

e Institute for Family Studies & Wheatley Institution (2019).

f UNICEF (2021).

g CIA (2021).

h Hauser Global Law School & New York University School of Law (2021).

i Punjab region only.

Previous literature and current study

Previous comparative studies of child support policy in high-income countries show that these countries have fairly well-developed child support policies, and in several countries these policies reflect a principle that children should not be financially disadvantaged by their parents not living together (Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cuesta, Haapanen and Meyer2022). Moreover, responsibility for the economic well-being of the child of separated parents rests within the nuclear family (or is shared between the nuclear family and the state). As a result, one parent typically owes the other parent a stated amount of money, and countries then typically monitor and enforce this obligation. A focus on children’s rights in these countries means that children born within or outside a marriage are generally treated equally, as are boys and girls.

Countries differ in the parties involved in the determination of child support (Corden, Reference Corden1999; Skinner, Bradshaw, & Davidson, Reference Skinner, Bradshaw and Davidson2007). Based on a recent review of 19 high-income countries (Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cuesta, Haapanen and Meyer2022), the most common scheme, found in nine countries, uses courts. Five countries mainly use an agency, and another five can be described as hybrid systems in which both the courts and another agency/institution are involved. Countries use different methods to calculate the amount of child support due, but important factors across countries are the economic resources of both parents, children’s needs and age, parental obligations to other children and child’s care time. Some countries use rigid formulas to determine the amount; some encourage parents to come to their own arrangement (which sometimes must be institutionally ratified to be enforced); and some have guidelines which are used as references but are not necessarily determinative. A few countries allow decision-makers substantial discretion. These procedures can lead to substantially different amounts due across countries, with the US generally expecting high levels of support, and Scandinavian countries expecting relatively little. Approaches to dealing with non-payment in high-income countries include focusing on enforcement, threats, and potentially punishments and/or trying to provide services that enable parents to pay (and trying to ensure that obligations are not set so high that they cannot be paid). In some high-income countries, the government guarantees a certain amount of support if the liable parent does not pay (Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cuesta, Haapanen and Meyer2022). Whether the policies in middle- and low-income countries can be described in the same way is not yet known.

A small research literature on child support receipt across high-income countries exists (Chung & Kim, Reference Chung and Kim2019; Hakovirta, Reference Hakovirta2011; Hakovirta & Mesiäislehto, Reference Hakovirta and Mesiäislehto2022; Maldonado, Reference Maldonado2017). We are aware of only one study that compares child support receipt across middle- and low-income countries in Latin AmericaFootnote 2 (Cuesta et al., Reference Cuesta, Jokela, Hakovirta and Malerba2019) and one study that compares a high-income country with a middle-income country (Cuesta & Meyer, Reference Cuesta and Meyer2012). An important finding of this literature is that low rates of child support receipt is a core issue across a wide range of countries. In 2013, approximately one-third of single-parent families were receiving child support in Colombia, Panama and Peru while less than 15 per cent of these families did so in Guatemala and Paraguay (Cuesta, Hakovirta, & Jokela, Reference Cuesta, Hakovirta and Jokela2018). Child support rates are relatively higher in Europe: a recent study finds that at least 50 per cent of lone mothers received child support in 16 of the 21 European countries included in the study (Hakovirta & Mesiäislehto, Reference Hakovirta and Mesiäislehto2022). Nevertheless, in the UK, France, Ireland and Luxembourg child support receipt rates were below 30 per cent (Hakovirta & Mesiäislehto, Reference Hakovirta and Mesiäislehto2022), similar to the rates observed in some Latin American countries. The amount of child support received also varies substantially between countries. Hakovirta and Mesiäislehto (Reference Hakovirta and Mesiäislehto2022) find that in European countries, lone mothers in the lowest income quintiles are more likely to receive child support than those who are better off; this pattern would follow from an approach in which child support was seen as primarily for those who need it the most. Receipt rates and amounts could be lower in middle- and low-income countries because on average non-resident parents will have lower incomes, but this has not yet been fully explored.

Methods

Systematic review

To be able to answer the first question of the study, between March and April of 2022, we conducted a systematic review of publications on child support policy in middle- and low-income countries. Our goal was to gather all relevant publications on child support policy from as many middle- and low-income countries as possible. The publications could include articles, books or book chapters and reports. The key words used in the search were the synonyms “child support” and “child maintenance.” The search was refined with additional search words related to parental separation or divorce and child support policy.Footnote 3 The publications were to be written in English and published from 2010 to 2021. Searches were conducted in SocINDEX, Heinonline and Google Scholar databases. We also included 17 publications outside of the systematic review that provided unique information on countries that would not have otherwise been included.

We selected the publications to be included in our review in two stages. In the first stage, we identified publications that met the broad search criteria, reviewed them briefly, and then selected any publication that was relevant based on title and abstract. In the second stage, the publications that made the first cut were carefully reviewed. Publications not fitting the criteria relevant to answer our research questions were excluded. This second stage yielded a total of 84 publications that were used to describe child support policy in 35 middle- and low-income countries in terms of institutional arrangements, procedures for determining child support amounts, and enforcement actions.Footnote 4 To ensure rigor, three of the authors and a research assistant participated in reading the 84 publications included in the review, with at least two individuals reading each publication. Where there was disagreement about how to present the information, at least one of the authors and the research assistant came to consensus on the presentation.

Child support receipt outcomes

Data

For our analysis of the proportion of separated parents who receive child support and the amount received, we used the LIS Database. LIS is an ideal source for cross-national comparative research because it provides data on individuals (microdata) and the information has been “harmonised” across approximately 50 countries in Europe, North America, Latin America, Africa, Asia and Australasia. The process of harmonisation takes individual data elements from a country’s own survey and makes them comparable to the data elements from other countries. Currently, LIS has information on child support receipt for eight middle- and low-income countries: Dominican Republic, Egypt, Guatemala, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Russian Federation and Serbia. We also created equivalent variables for Colombia using the 2016 Quality of Life Survey (QLS). Finally, to set the context of our findings for middle- and low-income countries, we also created equivalent variables for high-income countries included in LIS that have data on child support receipt: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Spain, UK, US and Uruguay. Information is from 2016 or the nearest year.

Sample

In each country, we first limit our analysis to families with children (up to age 17). We show the proportion of families with children that are lone-mother families and lone-father families. Note that some separated parents re-partner/remarry; although these families are potentially eligible for child support if the other parent is still living, we cannot identify them in this data source, so instead we focus on lone-parent families. We further limit the sample to lone parents who are not widows/widowers, since child support is not relevant if the other parent is not alive. Finally, because much of the policy discussion is about lone mothers (rather than lone fathers), our base results include only lone mothers; results for lone fathers are available in the Supplementary Material. The total number of observations of lone-mother samples varies from 466 in Egypt to 7,213 in the Russian Federation.

Measures

We use LIS harmonised variables and the Colombian QLS to create a country-specific poverty measure, defined as 50 per cent of median family income (as adjusted by family size). We show the simple head count (the proportion of families below this threshold). In the countries we examine, LIS includes a variable for the whether child support is received, and its amount.Footnote 4 We translate amounts from each country’s currency into 2016 U.S. dollars using Purchasing Power Parities (PPPs), a method for standardising amounts between different currencies. To explore how child support varies across the income distribution, we divide lone mothers into income quintiles, using the measure of income typical in the country, and subtracting child support.Footnote 5

Approach

We use weighted descriptive statistics. We show the proportion of lone-parent families among families with children and the proportion below the poverty threshold to provide context for our study. Our main analysis compares the proportion with any child support, and average amounts for lone-mother families within each country, overall and separately by income quintile. We do not show statistics when they are based on fewer than 30 observations.

Results

How do middle- and low-income countries approach child support policy?

This section provides a brief overview of what is known about institutional arrangements in 35 middle- and low-income countries, procedures for determining financial obligation, and policies for enforcing payments (detailed table provided in the Supplementary Material). Our description of child support policies is based on statutory law as found in the systematic literature review, unless otherwise noted. For countries with multiple legal systems, we present results according to the system that the source describes. In the table provided in the Supplementary Material, cells are blank if information was not available in the systematic review.

Compared to high-income countries, child support policies in middle- and low-income countries have some unique features. First, as noted before, several middle- and low-income countries recognise more than one legal system, each with its own rules about divorce, separation, and child support. Thus, in some countries religious and civil law and perhaps even customary law may co-exist, and the existence of multiple legal systems can cause distortions in the implementation of the rights and duties of parents in some countries (Eisenberg, Reference Eisenberg2011; Ramadan, Reference Ramadan2020). Another difference from high-income countries is that in some middle- and low-income countries children are still considered property of the father (Adelakun-Odewale, Reference Adelakun-Odewale, Beaumont, Hess, Walker and Spancken2014; Ntoimo & Ntoimo, Reference Ntoimo and Ntoimo2021). For instance, in rural areas of Africa where customary marriages dominate, the most common form of divorce is a simple repudiation of the marriage, and women have no rights to child support (or alimony) (Bouchama et al., Reference Bouchama, Ferrant, Fuiret, Meneses and Thim2018). Not seeing child support as the child’s right can also be seen in that in some countries children born outside marriage have either different rights or no right to child support from their non-resident parents (Eisenberg, Reference Eisenberg2011). In Nigeria, Indonesia, Malaysia and Russian Federation children born outside the context of legal marriage are not considered eligible for child support. A final difference from high-income countries is that in Pakistan, there are different rules for child support for boys and girls; this gender distinction does not exist in high-income countries.

Institutional arrangements

To describe the parties involved in child support determinations, we use the court/agency/hybrid categorisation that has been used for high-income countries, providing the first extension to middle- and low-income countries. In most countries it is possible for parents to make their own agreements that will have some standing. However, in some of these countries private arrangements must be either ratified in court (Ethiopia, Tunisia, Papua New Guinea and Turkey) or certified by a notary, public prosecutor, or a public attorney (Kazakhstan, Russian Federation, Brazil and Georgia) to be binding. Parents can also request assistance from a government or non-governmental agency to assist with their private negotiations.

We also examine whether agreements are made primarily by courts or by an agency. In all countries, the court is involved for formal determinations of child support. However, there is diversity in how they accomplish this. Courts in many cases are automatically involved in the determination of child support obligations in the case of divorcing parents and can also act to ratify the private agreements of cohabiting parents who are dissolving their union. Courts also often become involved when parents cannot agree. Very few of these countries rely only on agencies. Countries which have an administrative body or agency responsible for either some or all of the assessment, collection and transference of child support obligations include Ghana and El Salvador. In Peru, there is an agency that provides mediation or that supports and advise parents as they make their own arrangements, but this agency does not have responsibility for determining amounts. In Colombia, both courts and agencies are involved. In summary, in most countries, the court has a major role in determining child support amounts. In most of these countries there is no agency that has a major role in the setting of orders, and in some countries even when there is an agency, its actions need to be ratified by a court.

Procedures for determining how much child support is due

The factors considered in the formal determination of child support in middle- and low-income countries are very similar to those taken into account in high-income countries (Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cuesta, Haapanen and Meyer2022): the resources of the non-resident parent and/or resident parent, children’s needs and age, and obligations to other children and child’s care time. We consider whether there are rules for the determination of child support payments and whose incomes are assessed in this process. In most countries, the resources of both parents are incorporated within the rules generally used. In seven countries (Tunisia, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Vietnam, Dominican Republic and Mexico), only the non-resident parents’ incomes are explicitly considered.

As in high-income countries, there are no universal calculation methods for child support; obligations can be set in various ways, and child support determination can range from full discretion to rigid formulas. In most countries in our sample those authorised to determine child support amounts have full discretion. In countries in which there are some rules within a general framework of discretion, there is variation in the type of rule considered. For instance, in Ukraine (and within regions, in Vietnam) a minimum amount must be ordered while in Botswana, Zambia, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Panama, Peru and Romania the amount ordered is capped. Few countries have formal guidelines that suggest (but do not require) a particular amount. Only the Russian Federation uses a rigid formula, setting orders based on percentage of non-resident parent income.

Procedures for enforcing child support obligations

A child support obligation does not automatically mean that the amount will be paid. All high-income countries face challenges related to non-payment, and countries have developed different institutions and mechanisms to enforce compliance with child support obligations (Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cuesta, Haapanen and Meyer2022). In the middle- and low-income countries for which we found information, almost all have some procedures for dealing with default. The institution(s) responsible for enforcement varies. Most often courts retain responsibility for enforcing child support payments. This is the case in Latin American and African countries. In some countries, like Ghana, Nigeria, Kazakhstan, Vietnam and El Salvador there are governmental departments or agencies that are responsible for enforcing support. In our systematic review, only Indonesia does not have sanctions for non-payment.

In addition to the institution responsible for enforcement, tools for enforcement can differ. In most countries, typical enforcement actions include attachment of income and property and wage garnishment. Other enforcement tools available in several countries include fines, reporting to credit bureaus, prohibition of international travel (either retaining passports or providing identification of non-compliers to airport authorities), and driver’s license suspension. In Mexico and Peru failure to pay child support may lead to the non-resident parent’s inclusion in a child support debtor registry. Almost all countries also include jail time and imprisonment among the enforcement actions. In Papua New Guinea, child support debtors can be sentenced to imprisonment with hard labour. In our systematic literature search, we found no published research on how often various enforcement actions are taken or their effectiveness.

As noted above, many European countries have approached non-payment by providing a public guarantee of a minimum amount of child support (Hakovirta et al., Reference Hakovirta, Cuesta, Haapanen and Meyer2022). We could not find middle- and low-income countries that had a guaranteed child support scheme except for Georgia. There, when there is a formal order but child support is not paid, the child can receive support from the Child Support Fund (Japaridze, Reference Japaridze2013).

How many lone mothers are there, how many receive child support, and how much is received in these countries?

We now turn to analyses of nine countries with data on individuals. Figure 1 shows information on the prevalence of lone-parent families among all families with children. Rates vary considerably, from 6.7 per cent to 31.8 per cent. The three countries in the Eastern hemisphere have the same or lower rates than the six countries in the Western hemisphere. Egypt’s rate is particularly low in this context, and Colombia’s is particularly high. All countries except Serbia have many fewer lone-father families than lone-mother families, contributing to our focus on lone-mother families. The figure suggests that child support policy is potentially important to many families in these countries.

Figure 1. Proportion of lone-parent families among families with children.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on LIS and QLS.

Figure 2 displays poverty rates for the family types. In all countries except Peru, the poverty rate for lone-mother families is higher than for two-parent families (which includes some families in which a child lives with a parent and stepparent). The rate for lone-mother families is particularly high, with more than one in four poor in Egypt, the Russian Federation, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Panama and Paraguay. Lone-mother families have higher poverty rates than lone-father families in all countries except Serbia, typically by at least five percentage-points. The figure demonstrates the economic vulnerability of lone-mother families, highlighting the potential of child support to be important to well-being.

Figure 2. Poverty rate by type of family.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on LIS and QLS.

Table 2 provides our central results for child support receipts. In the Dominican Republic and Peru, 45 per cent of lone mothers receive some support; and support is nearly as common in Panama and the Russian Federation, where 36–43 per cent of lone mothers receive some child support. Support is less common in Colombia, Paraguay and Serbia, where 18–26 per cent receive, and it is infrequent in Egypt (6 per cent) and Guatemala (15 per cent). The amount received among recipients also varies, with recipient lone mothers in Panama and Serbia receiving an average of more than $4,000/year, and recipients in Colombia and Guatemala receiving less than $3,000, with the other countries in between. Median amounts received are somewhat lower in every country, reflecting that a relatively small number of lone mothers receive substantial amounts of support, bringing up the average.

Table 2. Child support outcomes among lone-mother families.

a Estimate is not available because cell size is lower than 30 observations.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on LIS and QLS.

Do these data reveal the policy logic that countries follow? One potential approach to child support policy is to expect relatively small amounts of support, but to expect it from almost all parents. Another approach would be to expect support only of the non-resident parents with the most resources, who would then be expected to pay more substantial amounts. If these two alternative approaches do describe the main choices, we should see some countries with a high proportion of lone parents receiving support, but those that do receive, receive relatively low amounts; we would also see other countries with a low proportion receiving, but receiving higher amounts. Figure 3 shows that these patterns do not describe our countries. The country with the highest amount received per recipient, Panama, does not have the lowest proportion receiving. Nor do the countries with the lowest amounts among recipients, Colombia and Guatemala, have high proportions receiving. Other factors are apparently operating.

Figure 3. Child support receipt: proportion receiving and average amounts.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on LIS and QLS.

Examining child support within income quintiles may provide more insight to the policy logic that countries follow. One potential conceptual approach is to attempt to have child support be directed at those with the least income. Under this approach, those in the lowest income quintile should be most likely to receive. An alternative approach is to attempt to have non-resident parents pay what they can. Because individuals are likely to partner with those of similar socioeconomic circumstances, this would result in the lone parents in the highest quintile being most likely to receive and to receive the most, since they will likely have been partnered with the highest-income liable parents.

Returning to Table 2, some countries fit these patterns. For example, in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Paraguay and Peru, the highest receipt rates are among the poorest lone mothers, the result that would follow if those in the most need are most likely to be helped. In contrast, in the Russian Federation, the highest receipt rates are in the richest quintile, and amounts generally increase as one moves into higher quintiles, the result that would follow if the ability to pay were paramount.

However, the results are not necessarily consistent. In Colombia, Paraguay and Peru, three countries in which the poorest parents are most likely to receive, amounts are relatively similar across income quintiles (the difference between the highest amount and the lowest amount is less than half of the lowest amount), which would not necessarily follow from a needs-based approach. In Panama, the proportion receiving is relatively stable across quintiles, but average amounts generally increase as one moves into higher quintiles (the amount in the top quintile is more than twice that of the lowest quintile), so it is not clear if this is an ability to pay approach. Overall, we cannot infer a consistent logic across countries, but difficulties with implementation may impede our ability to infer the policy logic.

Discussion

Even though the number of children in lone-parent families is large and increasing in many countries, and even though they face economic vulnerability, we know relatively little about the variety of policies directed towards their economic well-being in middle- and low-income countries. A research base exists on the kinds of government benefits available to lone-parent families in various countries around the world, but very little is known about how countries regulate economic transfers from a non-resident parent to a lone-parent family, nor about their effects. This study, which takes a two-pronged approach to describe child support policy (based on a systematic literature review) and to present recent information on its outcomes in terms of child support receipts for all middle- and low-income countries in LIS is the first step towards filling this gap.

We discuss our findings in the context of potential differences between high-income countries and the countries we study. One difference in some of our countries is that the nuclear family is not necessarily seen as the key unit of society. In higher-income countries, child support policy can be seen as flowing from an assumption that the nuclear family is paramount, so if parents do not live together, the government can regulate how financial resources flow from one parent to the other. But in a society in which the extended family, or the clan, is the primary unit, the governmental role when a couple separates is less clear. The child could be economically absorbed into the larger kin-based network, and there need not be a formal system for assessing amounts to be transferred from an individual non-resident parent. Alternatively, an amount could be expected, but it would be expected not necessarily from an individual non-resident parent but perhaps from the kin network of the non-resident parent. While these types of arrangements may in fact occur in practice, there is little written in the research literature documenting these types of arrangements. Instead, we find that these countries have policies in place to assign an expected amount from a non-resident parent (not his or her kin), and nearly all countries have procedures that can be followed in the event of non-payment, with penalties being assessed to the non-resident parent (not his or her kin).

A second area in which there may be differences is in the extent of the formal and informal economy. In high-income countries, there is generally an expectation that a non-resident parent can obtain employment (or can receive government benefits if not able to obtain employment), so this income can be identified and assessed. Moreover, asking employers to withhold amounts of child support, either pro-actively (to prevent problems) or in response to delinquency, is an option for many families. In contrast, in countries with informal sectors as large as those shown in Table 1, the identification of economic resources (income) is typically less precise, making the determination of an appropriate amount to be transferred challenging. Moreover, if the proportion of individuals self-employed, as independent contractors, as casual workers, or in illegal sectors is large, collection methods that are widely effective (like withholding from wages) are also challenging to identify.

A third area of difference is the unitary legal scheme in high-income countries, and the possibility of multiple legal systems in some middle- and low-income countries. This means describing policy for separated families in some countries included in this study can be quite complex, and there is even less data than in high-income countries on which to determine how the various systems are working.

A fourth area of difference is that in some of these countries there are differences in the rights available to children born inside versus outside of a marriage. Because divorce is a legal event, there is an arena (the judicial setting) in which countries can regulate financial transfers between parents to care for the children after divorce, and countries can review these policies in light of children’s right to receive child support (United Nations, 1989). In other countries, including some in this analysis, an important path to living with a lone parent is the dissolution of parental cohabitation. The children of cohabitors often have fewer rights than children of marriage (Miho & Thévenon, Reference Miho and Thévenon2020). If cohabitation dissolution is not a legal event, then countries need to examine whether there are easily accessible ways for parents to ensure that the child’s economic needs are considered post-separation, so that parental marital status does not determine the level of rights available to children.

Finally, the way that gender intersects with child support policy may also differ across countries. We have noted the historical pattern for children to be the property of fathers in many societies, and that this continues in some of the countries we study. This may lead to children being placed with the father upon separation, who will also generally have more economic resources than the mother in these countries. If the dominant pattern is that lone fathers have more economic resources than the non-resident mothers, and a country is primarily concerned about economic well-being, this would make child support a less salient issue. At the same time, if children do live with the mother in a patriarchal country, the father’s relative power may mean that he is not required to provide economic support, leading to economic hardship for his children.

These contrasts between high-income and middle-/low-income countries may mean that child support is less likely, and lower, in these countries. Using comparable data from high-income countries, we found that indeed fewer lone mothers receive child support in middle- and low-income countries, averaging 40 per cent across high-income countries and 28.7 per cent across our middle- and low-income countries. Moreover, when something is received, it is less in our countries, averaging $3,626 across middle- and low-income countries, compared to $5,260 in high-income countries. However, we would not characterise these differences as particularly large: both the proportion receiving support and the average amounts received are about 40 per cent higher in high-income countries. This may suggest that some of the difficulties revealed in the research on higher-income countries (eg. difficulties determining amounts from low-income liable parents, difficulties assessing appropriate amounts when parents have had multiple families, difficulties collecting from economically precarious liable parents) may also be relevant for middle- and low-income countries.

These differences between high and middle or low-income countries mean that policy lessons from high-income countries are not easily translatable to other contexts. Indeed, we think the policy implications that can be identified thus far are general, that countries need to consider their policies that provide support to lone parents, both the policy intents and the actual implementation. Moreover, the balance between expectations of resources from the non-resident parent versus government benefits needs careful review. Finally, countries need to consider the extent to which marital and non-marital children are treated equally and to pay special attention to the way that gender interacts with child custody and child support policy.

The lack of detailed policy implications is in part due to a lack of research. This analysis provides the current extent of knowledge on child support policy in 37 middle- and low-income countries, but our analysis is based on 84 publications. Additional research covering more countries (or more types of literature) could add to this effort. For example, while this research has described how child support obligations are calculated in some countries, we do not know anything about the level of support expected across countries. Research using vignettes to identify child support expectations for some typical families could be very useful and further understanding of whether a country has a low level of child support primarily because only a low amount was expected or because more was expected but it was not paid.

In addition to the limited extant research that provides descriptions of policy, there is even less published research on the outcomes of policies. We have used the main source of data on individuals across countries, LIS, but additional data sources, including using a country’s own surveys, could be useful. Addressing these issues will enable further assessment of which policies work, and in what context they work. This assessment has the potential to improve the well-being of economically vulnerable children in lone-parent families.

Acknowledgement

We thank Rebecca Jensen Compton and Eija Lindroos for providing excellent research assistant.

Ethics approval

According to U.S. federal regulations 45 CFR 46.102, this research does not encompass human subjects research since there was no intervention or interaction with the individuals, the data were not collected for the specific purpose of this research, and the data analysed is de-identified with the investigators/authors denied access to the code. The investigators/authors confirmed the status of the research as not including human subjects via the Rutgers University Non-Human Research Self-Certification Tool. Thus, the data used for this research is in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland Flagship Programme (decision number 320172) and the Academy of Finland project funding (decision number 338282).

Notes on Contributors

Laura Cuesta is an Assistant Professor of Social Work at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. Mia Hakovirta is a Senior Research Fellow at the INVEST Research Flagship Center, University of Turku, Finland. Mari Haapanen is a Doctoral Student at the INVEST Research Flagship Center, University of Turku. Daniel R. Meyer is an Emeritus Professor of Social Work at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. All authors conduct cross-national research on family and child support policy with a focus on separated families and their economic well-being. Their work has been published in leading academic journals on social policies and family change.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/ics.2023.4.