Introduction: What Was Arianism?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 June 2021

Summary

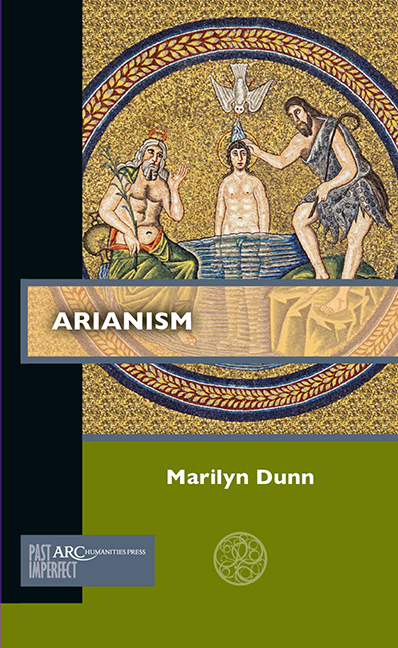

What was Arianism? Most people will only ever hear the word if they visit Ravenna in northeastern Italy and go into two of its stunning UNESCO world heritage sites: the church of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, originally the palace church of Theoderic the Great, the Ostrogothic leader who was de facto ruler of Italy from 493 to 526; and its contemporary, the Arian Bap-tistry. Thanks to the internet, you can now visit them from the comfort of your armchair and marvel at the beauty of their mosaics. On the Baptistry ceiling, a youthful and naked Christ stands in the River Jordan, flanked by John the Baptist on one side and on the other by a figure personifying the river; a dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit pours light from its beak on to his head. Here are two persons of the Christian Trinity, Son and Holy Ghost: by implication the third, God the Father, is also present, as a voice declaring that Jesus is his beloved son in whom he is well pleased (Matt. 3:13–17; Mark 1:9–11; Luke 3:21–23). Guides, guidebooks, and websites all note that Theoderic and the Goths were Arian heretics: Arius, the heresy's founder, had denied the divine nature of Christ and thus the equality of God the Son with God the Father.

Arianism is commonly summed up in two or three phrases: “Arius denied the divinity of Christ” (or “the unity of the Trinity”); “Arianism was subordinationist: it made the Son a lesser God than the Father.” But anyone attempting to dig deeper will swiftly become aware of the subject's complexity and breadth.

Modern approaches fall into three broad areas. The first covers Arianism's origins and emergence. This hinges on a basic narrative in which Arius, a priest of Alexandria in Egypt in the early fourth century, proposed a radical theology in which the Son was “not part of God and could never have been ‘within’ the life of God” but was “dependent and subordinate” (Williams, Arius, 177). He was condemned at the Council of Nicæa, called by the Emperor Constantine in 325, where the Nicene Creed, which said that Father and Son were “of the same substance,” was proclaimed as the universal creed of the Empire. However, Arius's condemnation was swiftly followed by the removal of many of his opponents, in a conspiracy masterminded by his supporter, Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Arianism , pp. 1 - 8Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2021