Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword: Bill Freund and the Making of His Autobiography

- Family Tree

- A Brief Introduction

- 1 The Austrian Past

- 2 The Aftermath of War: A Perilous Modernity

- 3 The Dark Years

- 4 A New Life in America

- 5 Adolescence: First Bridge to a Wider World

- 6 As a Student: Chicago and Yale

- 7 As a Student: Africa and England

- 8 The Tough Years Begin

- 9 An Intellectual and an African: Nigeria

- 10 An Intellectual and an African: Dar es Salaam and Harvard

- 11 South Africa, My Home

- Notes

- Select Bibliography of Bill Freund’s Publications

- List of Illustrations

- Author’s Acknowledgements

- Supplementary Acknowledgements

- Index

9 - An Intellectual and an African: Nigeria

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 June 2021

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword: Bill Freund and the Making of His Autobiography

- Family Tree

- A Brief Introduction

- 1 The Austrian Past

- 2 The Aftermath of War: A Perilous Modernity

- 3 The Dark Years

- 4 A New Life in America

- 5 Adolescence: First Bridge to a Wider World

- 6 As a Student: Chicago and Yale

- 7 As a Student: Africa and England

- 8 The Tough Years Begin

- 9 An Intellectual and an African: Nigeria

- 10 An Intellectual and an African: Dar es Salaam and Harvard

- 11 South Africa, My Home

- Notes

- Select Bibliography of Bill Freund’s Publications

- List of Illustrations

- Author’s Acknowledgements

- Supplementary Acknowledgements

- Index

Summary

In order to make sense of this part of my life, I need to say a bit about Northern Nigeria and the society in which I was about to live for four formative years. Centuries before, this relatively well-watered and populous part of the West African savanna evolved a hierarchical multitude of mudwalled towns in which rulers, cognisant of Islam through trade, gradually adopted this sophisticated religion as a legitimating device as well as continuing to patronise older beliefs. At the start of the nineteenth century, a Muslim teacher initiated a spectacular series of jihads that expanded the writ of a more orthodox Islam and diffused Islamic culture especially in the towns, which were now graced with palaces and mosques. Kano became a great trading centre with North and North-East Africa; North Africa was clearly the model of progress. The overrule of the jihad centre of Sokoto was mostly accepted by the towns, including my new home of Zaria, well to the south of both Sokoto and Kano. This was a part of Africa that experienced an important developmental thrust. The Hausa language started to be written extensively in Arabic script; commerce and even craft manufacture flourished; a kind of bureaucracy developed. The British conquest occurred only after 1900, so the entire colonial period lasted just sixty years, really just a person's lifetime, and the system of indirect rule, for which Northern Nigeria was a model in Africa, at least meant that ‘native’ rulers with their retinues were propped up – assuming good behaviour – and the British presence was actually very limited.

Much of the economy, which featured wealthy merchants, remained outside European hands entirely, although peanuts and to some extent cotton were cultivated for export. Slavery, which had been very prevalent, gradually faded away. For me, an enjoyable aspect of daily life and of bigger trips involved visiting markets and admiring handicrafts and cloth for sale as well as gauging something of how people lived and interacted.

Northern Nigeria consisted of more than the related series of Hausaspeaking emirates. Not only did the countryside bear signs of an older culture (though much less by my time) but there were many areas, notably on high ground, difficult to control with cavalries, that continued to be inhabited by small, varied language groups, many dozens in fact.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

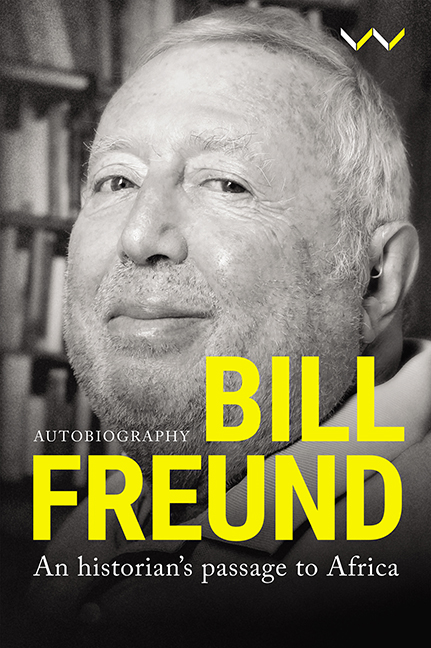

- Bill FreundAn Historian's Passage to Africa, pp. 119 - 140Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2021