Book contents

- The Cambridge Companion to Petrarch

- The Cambridge Companion to Petrarch

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Book part

- Chronology

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Part I Lives of Petrarch

- Part II Petrarch's works: Italian

- Part III Petrarch's works: Latin

- Part IV Petrarch's interlocutors

- Part V Petrarch's afterlife

- Part VI Conclusion

- Guide to further reading

- Index

- Cambridge Companions to…

- References

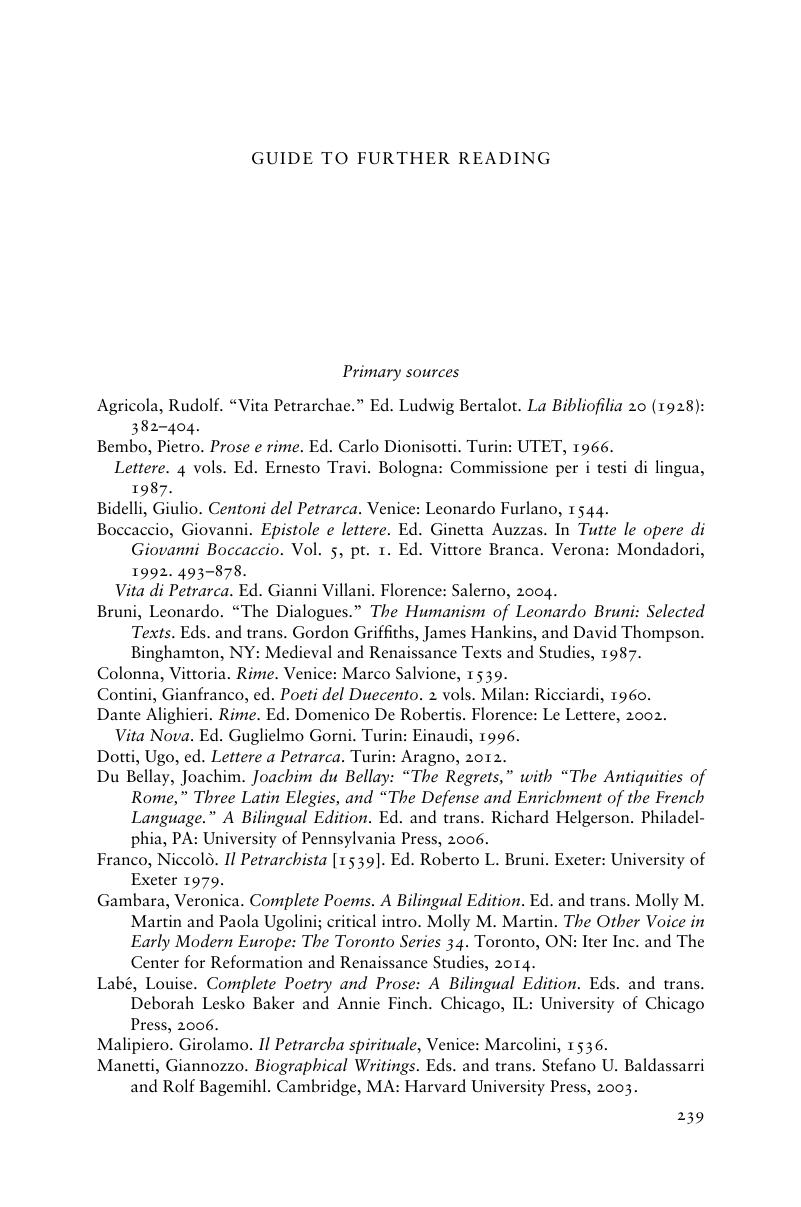

Guide to further reading

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 November 2015

- The Cambridge Companion to Petrarch

- The Cambridge Companion to Petrarch

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Book part

- Chronology

- Glossary

- Introduction

- Part I Lives of Petrarch

- Part II Petrarch's works: Italian

- Part III Petrarch's works: Latin

- Part IV Petrarch's interlocutors

- Part V Petrarch's afterlife

- Part VI Conclusion

- Guide to further reading

- Index

- Cambridge Companions to…

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Companion to Petrarch , pp. 239 - 251Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015