Book contents

- Captive Anzacs

- Australian Army History Series

- Captive Anzacs

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Note on terminology

- Glossary

- Maps

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Becoming prisoners of war

- Chapter 2 The circumstances of confinement

- Chapter 3 Shaping camp life

- Chapter 4 Outside connections

- Chapter 5 Reactions at home

- Chapter 6 After the Armistice

- Chapter 7 ‘Repat’ and remembrance

- Conclusion

- Book part

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

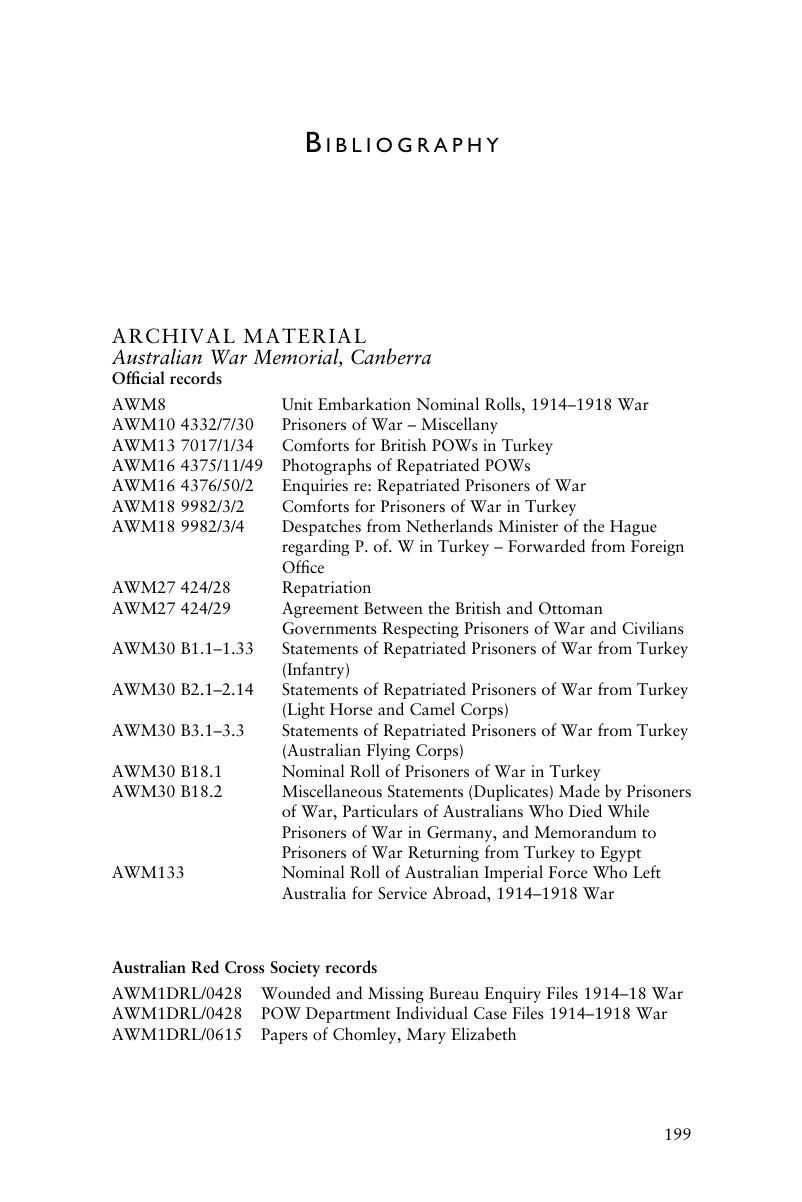

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 June 2018

- Captive Anzacs

- Australian Army History Series

- Captive Anzacs

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Note on terminology

- Glossary

- Maps

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Becoming prisoners of war

- Chapter 2 The circumstances of confinement

- Chapter 3 Shaping camp life

- Chapter 4 Outside connections

- Chapter 5 Reactions at home

- Chapter 6 After the Armistice

- Chapter 7 ‘Repat’ and remembrance

- Conclusion

- Book part

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Captive AnzacsAustralian POWs of the Ottomans during the First World War, pp. 199 - 215Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2018