Book contents

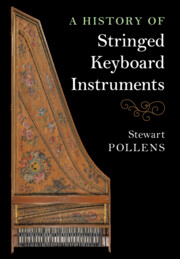

- A History of Stringed Keyboard Instruments

- A History of Stringed Keyboard Instruments

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Pitch Notation Conventions

- One Keyboard Origins

- Two Principles of Design and Construction

- Three The Henri Arnaut Manuscript

- Four The Renaissance

- Five The Baroque Period

- Six The Invention of the Piano

- Seven The Classical Period

- Eight The Romantic Era

- Nine Stagnation and Revival

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

- A History of Stringed Keyboard Instruments

- A History of Stringed Keyboard Instruments

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Pitch Notation Conventions

- One Keyboard Origins

- Two Principles of Design and Construction

- Three The Henri Arnaut Manuscript

- Four The Renaissance

- Five The Baroque Period

- Six The Invention of the Piano

- Seven The Classical Period

- Eight The Romantic Era

- Nine Stagnation and Revival

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A History of Stringed Keyboard Instruments , pp. 529 - 550Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022