Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Introduction

- Leisure and Associational Culture

- Leisure Spaces

- 3 Muscles and Morals: Children's Playground Culture in Ireland, 1836–1918

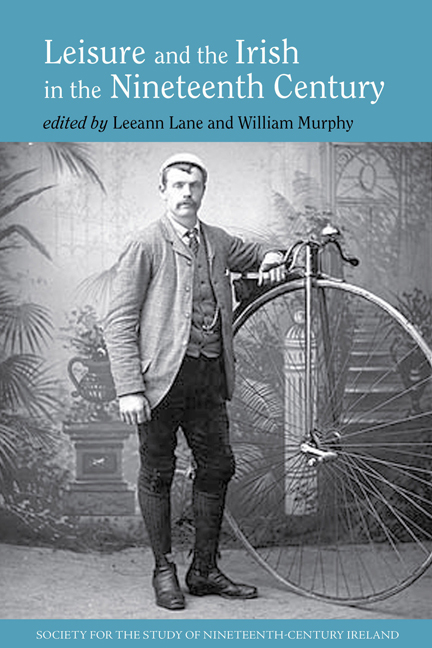

- 4 Photography and Leisure: The Rise of the Photographic Studio in Mid- to Late-Nineteenth-Century Dublin

- 5 The Establishment and Evolution of Limerick City Municipal Library, 1889–1938

- Leisure in Literature

- Leisure, Tourism and Travel

- Leisure and Female Élites

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

3 - Muscles and Morals: Children's Playground Culture in Ireland, 1836–1918

from Leisure Spaces

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Introduction

- Leisure and Associational Culture

- Leisure Spaces

- 3 Muscles and Morals: Children's Playground Culture in Ireland, 1836–1918

- 4 Photography and Leisure: The Rise of the Photographic Studio in Mid- to Late-Nineteenth-Century Dublin

- 5 The Establishment and Evolution of Limerick City Municipal Library, 1889–1938

- Leisure in Literature

- Leisure, Tourism and Travel

- Leisure and Female Élites

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Summary

The usefulness of these institutions [playgrounds] cannot be doubted by anyone who has once seen such grounds crowded with children thoroughly enjoying themselves, and unconsciously strengthening their limbs and constitutions by games and gymnastic exercises performed under the canopy of heaven.

On an autumn day in October 1911, the gates to a new children's playground opened at Cook Street, located in the medieval core of Dublin's south side amidst significant clusters of decaying poor housing, poor sanitary accommodation and general deprivation. This new urban play space immediately appealed to local children who played with skipping ropes and balls and participated in the game ‘oranges and lemons’. The demarcation of specialised public playgrounds that invented an ideological encoding of recreation for Irish urban children was developed extensively as the long nineteenth century drew to a close.

The Women's National Health Association of Ireland (WNHAI) commenced work on a second garden site for Dublin children in December 1911 on the newly created St Augustine Street. The name given to this garden site was St Monica's Garden Playground and it finally opened on 2 April 1912. The gate opened onto a flat space for games and there was a high wall at the back for handball. The elevated southern portion of this playground was used as a garden. This consisted of a lawn, borders against the walls for flowering shrubs, plants and some garden seats. The northern end consisted of a pit for sand that was disinfected every day and changed at intervals, and there younger children made sandcastles. There were six cradles made from banana crates in an adjoining shed for young children to sleep in the fresh air. The collection of toys included skipping ropes, balls, carpenters’ tools and garden implements. These were stored in a cupboard at one end of the tool shed and distributed to the children. A female nurse was employed to care for pre-school children who attended before one o'clock. Between 140 and 180 children attended on summer afternoons from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m., when a ‘lady supervisor’ replaced the nurse. As these sites testify, children's recreation and playground culture in Ireland emerged as a central site and process of identity construction, contestation and negotiation.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Leisure and the Irish in the Nineteenth Century , pp. 61 - 79Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2016