Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- 1 Memories of Dan Dare

- 2 Science Fiction and Selective Tradition

- 3 Science Fiction and the Cultural Field

- 4 Radio Science Fiction and the Theory of Genre

- 5 Science Fiction, Utopia and Fantasy

- 6 Science Fiction and Dystopia

- 7 When Was Science Fiction?

- 8 Where Was Science Fiction?

- 9 The Uses of Science Fiction

- Works Cited

- Index

2 - Science Fiction and Selective Tradition

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Figures

- 1 Memories of Dan Dare

- 2 Science Fiction and Selective Tradition

- 3 Science Fiction and the Cultural Field

- 4 Radio Science Fiction and the Theory of Genre

- 5 Science Fiction, Utopia and Fantasy

- 6 Science Fiction and Dystopia

- 7 When Was Science Fiction?

- 8 Where Was Science Fiction?

- 9 The Uses of Science Fiction

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

To summarise the tentative conclusions of the previous chapter, I have argued that the category of SF applies meaningfully across a whole range of cultural forms, from the novel and short story to film and television, a generic continuity repeatedly signalled by way of intertextuality; that SF cannot be located exclusively on either side of any high Literature/popular culture binary, but should be seen as straddling and thereby, in effect, deconstructing them; that SF tends to be resistant to modernist aesthetics insofar as it privileges content, that is, ideas, over form; and that SF narratives are typically tales of resonance and wonder, in which quasi-ideological resonance functions primarily so as to add plausibility to the tale's wondrous core. Thus far, I have treated as SF whatever calls itself thus, but the question of definition can be postponed no further. If Le Guin is right that everybody is writing SF now, even Winterson, then it is time we attempt to describe what exactly it is they are writing. But Winterson is by no means alone in refusing the generic label ‘science fiction’ – here, it becomes necessary to spell the term out in full – nor with paying for that refusal at the price of Le Guin's heartfelt condemnation. Two years later, Margaret Atwood's insistence that her novels Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood were ‘speculative fiction’, but not thereby ‘science fiction’, prompted a very similar reaction (Le Guin, 2009). Atwood held her peace at the time, but eventually replied at length.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

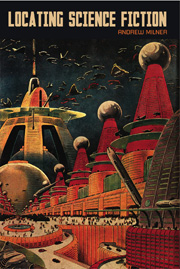

- Locating Science Fiction , pp. 22 - 40Publisher: Liverpool University PressPrint publication year: 2012