Introduction

There is an established association between fire-setting and mental disorder. However, the specific nature of this relationship has been complex and difficult to characterise, particularly for those within forensic and custodial settings. Compared to other areas of challenging behaviour, offending and mental health, there is very little research, despite many decades of evidence intimating a relationship. Following a rapid expansion of forensic psychiatric services in the United Kingdom during the 1980s to early 2000s, the non-forensic clinician may have not had as great an exposure to individuals in whom fire-setting is a prominent feature of presentation or history. However, as the expansion of the secure estate has plateaued, it is increasingly common for the non-forensic clinician to encounter fire-setting behaviour in patients either in their risk history or as part of the presentation leading to admission, or while an inpatient in non-secure services. Furthermore, this behaviour may or may not be a manifestation of an active mental disorder and may lead to legal proceedings through the criminal justice system coinciding with periods of assessment and treatment. It is therefore important that the needs of this group of patients, which may traditionally be more familiar to forensic clinicians, are borne in mind by all mental health professionals.

In this chapter, we define the terminological differences between the terms ‘fire-setting’, ‘arson’ and ‘pyromania’, including their place in current diagnostic manuals. We present an epidemiological perspective on fire-setting in those with mental disorder and describe classification systems and theories of fire-setting with prevailing conceptual models of fire-setting and mental disorder. We also discuss current approaches in the risk assessment of fire-setting and consider psychological and pharmacological interventions in fire-setting. Finally, we suggest a care pathway to guide clinical and risk assessment of the patient with fire-setting as a feature of their behaviour or history.

Fire-Setting, Arson and Pyromania: Crime, Behaviour and Mental Disorder

Many professionals may understandably use the terms ‘fire-setting’, ‘arson’, and ‘pyromania’ interchangeably. However, these terms can have differing diagnostic, aetiological and legal implications (see Box 10.1, adapted from Reference Dickens, Sugarman, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonDickens and Sugarman, 2011). Fire-setting is an act or a behaviour without inference of intent (indeed, fire-setting can be accidental), arson is a criminal offence and pyromania is a mental disorder. Since 1994, the UK Fire Rescue Service has classified fires at a high level into categories of primary, secondary, deliberate and accidental (see Box 10.2).

Box 10.1 Definitions

1. The Crime – Arson: The crime of arson is defined within Section 1 of the Criminal Damage Act 1971 c. 48. It relates to:

(1) A person who without lawful excuse destroys or damages any property belonging to another intending to destroy or damage any such property or being reckless as to whether any such property would be destroyed or damaged shall be guilty of an offence.

(2) A person who without lawful excuse destroys or damages any property, whether belonging to himself or another:

(a) intending to destroy or damage any property or being reckless as to whether any property would be destroyed or damaged; and

(b) intending by the destruction or damage to endanger the life of another or being reckless as to whether the life of another would be thereby endangered; shall be guilty of an offence.

(3) An offence committed under this section by destroying or damaging property by fire shall be charged as arson.

Thus ‘arson’ is the specific criminal act of destruction, comprising the specific criminal act of intention; an ‘arsonist’ has been convicted of the crime of arson.

2. The Behavioural Phenotype – Fire-Setting: A broad definition of fire-setting encompasses the behavioural phenotype consisting of deliberate setting of fires, which may or may not have been prosecuted for several reasons:

Insufficiently severe to cause damage

Fire not detected as deliberate

Not possible to identify who has set the fire

Insufficient evidence to secure a conviction

Young age of the fire setter

3. Pyromania: According to the ICD11, pyromania (C670) is categorised as an impulse control disorder, also known as ‘pathological fire-setting’.

Pyromania is characterised by a recurrent failure to control strong impulses to set fires, resulting in multiple acts of, or attempts at, setting fire to property or other objects, in the absence of an apparent motive (e.g. monetary gain, revenge, sabotage, political statement, attracting attention or recognition).

There is an increasing sense of tension or affective arousal prior to instances of fire setting, persistent fascination or preoccupation with fire and related stimuli (e.g. watching fires, building fires, fascination with firefighting equipment), and a sense of pleasure, excitement, relief or gratification during, and immediately after the act of setting the fire, witnessing its effects, or participating in its aftermath.

The behaviour is not better explained by intellectual impairment, another mental and behavioural disorder, or substance intoxication.

Primary fires are reportable fires in specific locations, including all fires in buildings, vehicles and outdoor structures, any fire involving casualties or rescues, or fires attended by five or more firefighting appliances. They are reported in detail.

Secondary fires are reportable fires constituting most outdoor fires not occurring in primary fire locations or meeting the criteria for primary fires; they are reported in less detail.

Accidental fires include those fires for which the cause is not known or is unspecified.

Deliberate fires include those fires for which deliberate ignition is merely suspected.

Within this chapter, we restrict our terminology as a default to ‘fire-setting’ and reserve the term ‘arson’ for a distinct sub-group of fire-setting that has attracted a conviction, or as is referred to in cited texts. The term pyromania was first coined by Marc in 1833 (Reference RixRix, 1994; Reference Burton, Mcniel and BinderBurton et al., 2012) and defined by Kraeplin as a type of impulsive insanity (Reference Geller, Erlen and PinkusGeller et al., 1986). Its classification as a diagnosis has varied over recent decades, with an arguable trend toward de-medicalisation and one of questionable relevance. It began as an obsessive-compulsive reaction in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) before eventually being classified as an impulsive control disorder in the third edition (Reference Johnson and NethertonJohnson and Netherton, 2016). Today, pyromania continues to be defined as an impulse control disorder in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Edition (ICD11) (World Health Organization, 2022) criteria. However, this does not fully align with the DSM-5, whereby pyromania has been reclassified from being a standalone disorder to being grouped as part of the ‘impulse control disorders not otherwise specified’ (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Reference Ritchie and HuffRitchie and Huff (1999) found that only 0.1% of a sample of 283 individuals convicted of arson satisfied the diagnostic criteria for pyromania. This is a marked reduction from Reference Lewish and YarnellLewis and Yarnell’s (1951) seminal findings of 60% prevalence of pyromania among those convicted of arson. A 1967 study of 239 people convicted of arson found 23% to have underlying pyromania (Reference Robbins and RobbinsRobbins and Robbins, 1967). Several other studies in the 1980s and 1990s found a prevalence of pyromania of less than 3.3% in those convicted of arson (Reference Prins, Tennent and TrickPrins et al., 1985; Reference Geller, Erlen and PinkusGeller et al., 1986; Reference SoltysSoltys, 1992; Reference Lindberg, Holi, Tani and VirkkunenLindberg et al., 2005). This highlights that the act of fire-setting can have different motivations and aetiological factors and should not be viewed as pathognomonic of an underlying mental disorder such as pyromania. While mental disorders more broadly are over-represented in those who have set fires, including those convicted of arson, the prevalence of pyromania is unknown and thus should be considered a rare disorder.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of fire-setting in the United Kingdom is difficult to estimate accurately. Triangulation of data from various sources, including fire service responses, criminal justice services and self-report research surveys and clinical studies provides a helpful proxy.

According to the Office for National Statistics (2023), the total number of fires attended by the Fire and Rescue Service in England decreased for about a decade from its peak in March 2004 (474,000 fires) to March 2013 (154,000 fires). Since then, the total number of fires has varied between approximately 150,000 to 183,000 up until March 2022. Furthermore, the number of fire-related fatalities in England has declined since the 1980s and the number of non-fatal causalities from fire setting has trended downward since the mid-1990s. The number of deliberate fires attended was more than 66,000 in the year ending September 2022, which has continued a downward trend since the peak of more than 320,000 deliberate fires attending in 2003–4. The total number of deliberate fires in healthcare settings fell in absolute numbers between 2001–2 and 2011–12, though the data since then remains unclear. These data may reasonably be expected to reflect, in part, patients whom we encounter in mental health services.

Fire-Setting in the General Population

The most comprehensive study of fire-setting outside of a forensic population can be found in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Correlates (NESARC) from the United States (Reference Blanco, Alegría, Petry, Grant, Simpson and LiuBlanco et al., 2010). More than 43,000 adults aged 18 years or older living in households were interviewed face-to-face by US Census workers between 2001 and 2002. Sociodemographic factors were collated as well as DSM-IV diagnoses using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-DSM IV Version (AUDADIS-IV), a valid and reliable fully structured diagnostic interview designed for use by professional interviewers who are not clinicians. Diagnoses included in the AUDADIS-IV can be separated into three groups: substance use disorders (including any alcohol abuse/dependence, any drug abuse/dependence and any nicotine dependence); mood disorders (including major depressive disorder, dysthymia and bipolar disorder); and anxiety disorders (including panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobia and generalised anxiety disorder).

According to their results, the prevalence of lifetime fire-setting in the US population was 1.13 (95% CI [1.0, 1.3]). Fire-setting was strongly associated with deficits in impulse control, such as antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) (OR = 21.8; 95% CI [16.6, 28.5]), drug dependence (OR = 7.6; 95% CI [5.2, 10.9]), bipolar disorder (OR = 5.6; 95% CI [4.0, 7.9]) and pathological gambling (OR = 4.8; 95% CI [2.4, 9.5]). Associations between fire-setting and all antisocial behaviours were positive and significant. A lifetime history of fire-setting, even in the absence of ASPD diagnosis, was strongly associated with substantial rates of mental illness, history of antisocial behaviour, family history of other antisocial behaviours, decreased functioning and higher rates of treatment seeking. The researchers concluded that fire-setting may be best understood as a broader impulse control syndrome and part of the externalising spectrum of disorders.

In summary, NESARC demonstrated that a third of fire-setters had a diagnosable mental disorder and more than half were diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder and had a psychological motive during the time of reporting. Although there may be cultural and societal differences in translating this research to the UK population, the study by Reference Blanco, Alegría, Petry, Grant, Simpson and LiuBlanco et al. (2010) is useful at providing an evidence base for the prevalence of fire-setting behaviour and its association with mental disorders in the general population outside of forensic and custodial settings.

Data on Criminal Justice System and Mentally Disordered Offenders

Most epidemiological data relating to mental disorders and fire-setting have traditionally been sourced from forensic populations, including those convicted of arson who are then referred for psychiatric assessment or populations within secure mental health settings.

It is less common for charges to lead to a successful conviction in cases of arson compared to other types of offending. Arson convictions are estimated to be between 7% and 28%. In comparison, 44% of convictions are for offences against the person, 86% are for homicides and 94% for drug offences (Reference Averill, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonAverill, 2011). There have been several reasons postulated for this attrition, including an absence of witnesses and the deliberate classification made by the Fire and Rescue Service which prompts a criminal investigation that can be based on suspicion alone. It is therefore possible that the official statistics about the prevalence and impact of arson to individuals and society is an underestimation based on the manner in which the offence is dealt with by the criminal justice system (see Reference Kelly, Lovett and ReganKelly et al., 2005 for more information).

There are several points in legal proceedings where an individual may require assessment and treatment for a mental disorder when arrested on suspicion of arson. Individuals may be diverted to non-secure services upon arrest but before being charged. They may require assessment and treatment in hospital either as unsentenced or sentenced prisoners. They may also be evaluated by independent expert witnesses for consideration of a hospital disposal. According to Reference Tyler and GannonTyler and Gannon (2012), 42 of the 1,407 adult arson offenders (3%) brought before the courts in England and Wales in 2009 received combined hospital orders and custodial sentence. The role of the psychiatric expert witness in arson proceedings has been well described elsewhere (Reference Averill, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonAverill, 2011; Reference Burton, Mcniel and BinderBurton et al., 2012).

While there is a body of evidence to suggest that mental disorders are over-represented in those who have set fires, there does not appear to be any evidence to suggest that major mental illness directly causes fire-setting. Nonetheless, it is estimated that approximately one in 10 patients admitted to forensic psychiatry services has a history of fire setting (Reference Repo, Virkkunen, Rawlings and LinnoilaRepo et al., 1997; Reference Coid, Kahatan, Gault, Cook and JarmanCoid et al., 2001; Reference Fazel and GrannFazel and Grann, 2002; Reference Hollin, Davies, Duggan, Huband, McCarthy and ClarkeHollin et al., 2013).

In relation to quantifying the increased risk of mental disorder within a forensic psychiatric population convicted of arson, Reference Anwar, Långström, Grann and FazelAnwar et al. (2011) carried out a case–control study using data from Swedish national registers for convictions and hospital discharge diagnoses. They calculated odds ratios for men and women with arson convictions having a schizophrenia diagnosis as 22.6 and 38.7, respectively, and for any other psychosis as 17.4 and 30.8, respectively, noting that this association is much higher than for most other types of violent offending. Arguably, given the prominence of psychotic illness in the inpatient environment, this study (in conjunction with Reference Blanco, Alegría, Petry, Grant, Simpson and LiuBlanco et al., 2010) may provide one of the most helpful indicators of the attention that should be given to fire-setting screening, risk assessment and management in this group. Reference Ritchie and HuffRitchie and Huff (1999) also found in a sample of 283 cases of arsonists in the United States, that 90% had recorded mental health histories, 36% satisfied diagnostic criteria for major mental illness such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and 64% were abusing drugs or alcohol at the time of the index offence.

Reference Rice and HarrisRice and Harris (1991) examined the characteristics of 243 males convicted of arson within a maximum-security psychiatric facility in Canada. While only one subject had a diagnosis of pyromania, approximately half had a personality disorder and one-third had schizophrenia. Substance use disorders are also more common in both men and women convicted of arson (Reference Enayati, Grann, Lubbe and FazelEnayati et al., 2008).

The prevalence of mental disorders in those convicted of arson has been shown to be greater than those convicted of homicide (Reference Räsänen, Hakko and VäisänenRäsänen et al., 1995a, Reference Räsänen, Hakko and VäisänenRäsänen et al., 1995b). There are also more frequent histories of suicide attempts (Reference Burton, Mcniel and BinderBurton et al., 2012). Reference Yesavage, Benezech, Ceccaldi, Bourgeois and AddadYesavage (1983) found that 54% of those convicted of arson had a diagnosable mental illness, and that those who were also mentally ill set a greater number of total fires than those without a mental illness. Furthermore, it has been estimated that the prevalence of schizophrenia is anywhere from 4- to 20-fold greater in those convicted of arson compared to the general population (Reference Yesavage, Benezech, Ceccaldi, Bourgeois and AddadYesavage et al., 1983, Reference Räsänen, Hakko and VäisänenRäsänen et al., 1995b; Reference Anwar, Långström, Grann and FazelAnwar et al., 2011).

Children and Fire-Setting

Although beyond the scope of this chapter, which focuses primarily on adult fire-setting behaviour, there is a significant body of research that investigates juvenile fire-setting, which may be encountered in the history of an adult admitted to the psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU). Counter-intuitively, epidemiological surveys among children and adolescents across different countries have consistently suggested that ‘fire-interest’ is common and may be the norm, but that this may decline with age (MacKay et al., 2009). However, Reference 137Chen, Arria and AnthonyChen et al. (2003) identified several associations in adolescents which may suggest risk of a more deviant pattern of behaviour. These are detailed in Box 10.3.

Box 10.3 Associated Factors Indicating Risk of Persistent Fire-Setting Behaviour in Teenagers

Male

Young age

Dysfunctional family background

Stressful life events

Low socio-economic status

Academic or vocational difficulties

Fire-setting in children is commonly found in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder as well as the phenomenon of curiosity fire setting (Reference Johnson and NethertonJohnson and Netherton, 2016). While there are case reports of those diagnosed with pyromania (Reference Ceylan, Durukan, Türkbay, Akca and KaraCeylan et al., 2011), the evidence base for this diagnosis in children and young people is extremely limited.

Classification and Explanatory Theories of Fire-Setting

Motive-Based Classifications

Reference Lewish and YarnellLewis and Yarnell (1951) provided one of the earliest classification systems for fire-setters, including those who had set fires unintentionally through delusions, for erotic pleasure and to acquire revenge. While distinguishing between these groups lacked validity and reliability, the researchers did provide a foundation for further study of motive-based classifications, which, in turn, aims to better understand why people intentionally start fires. There have been many such theories in the decades since. However, some have been criticised for conflating motive with individual characteristics, particularly among those with a possible mental disorder. Furthermore, many of the identified motives may not be mutually exclusive and may overlap with one another, which, combined with their subjectivity, can create inconsistencies and confusion in these classification systems (Reference GellerGeller, 1992; Reference Gannon and PinaGannon and Pina, 2010; Reference Tyler and GannonTyler and Gannon, 2021). Without clear and discrete categories, the explanatory value in these typologies has also been brought into question.

Reference Canter and FritzonCanter and Fritzon (1998) developed a model that was notable for its theoretically informed development and incorporation of integrated action systems theory (Reference Tyler and GannonTyler and Gannon, 2021), which satisfies multiple criteria for evaluation of competing theories, including empirical adequacy, external consistency, unifying power, fertility and explanatory depth (Reference Fritzon, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonFritzon, 2011). Through their study of 175 arson cases dealt with by the courts, Reference Canter and FritzonCanter and Fritzon (1998) identified two underlying axes upon which the motivation of fire-setting behaviour could be understood. The first axis related to the target, either people or objects, and the second related to the purpose, either instrumental (e.g. associated with theft or concealment of crime) or expressive in itself. Their classification subsequently proposed four typologies, as shown in Box 10.4.

Box 10.4 Two-Axis Theory

| Object | |||

| Person | Object | ||

| Purpose | Instrumental |

|

|

| Expressive |

|

| |

Reference Harris and RiceHarris and Rice (1996) developed the first statistically derived typology by investigating a population of 243 male mentally disordered offenders with fire-setting history admitted to a high-security psychiatric setting. They recorded several variables as well as subsequent recidivism for fire-setting or other offences. Their analysis suggested four subtypes of offender, as shown in Box 10.5. Despite this nomenclature offering an alluring invitation to classify the motivation in simplistic terms, Reference Gannon and PinaGannon and Pina (2010) convincingly argued that this provides a two-dimensional picture and does not incorporate other elements, including, for example, personality factors and characteristics of the fires set, to provide unifying explanatory power.

Box 10.5 Harris and Rice Classification

Psychotics: 33% with few previous incidents of fire setting

Unassertives: 28% with little history of aggression and offending but considered to have revenge motivations

Multi-fire-setters: 23% with disturbed childhoods who are younger with criminal versatility and high recidivism risk

Criminals: 16% with disturbed backgrounds, likely to have personality disorder diagnosis, who are assertive and have a high risk of recidivism, including for new offences

A full history of typological classifications of fire-setting is provided by Reference Dickens, Sugarman, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonDickens and Sugarman (2011) and Reference Tyler and GannonTyler and Gannon (2021) for the interested reader.

Explanatory Models

Dynamic Pathways

Dynamic pathway models are data-driven models to generate theory based on qualitative research focused on descriptive accounts of context, thoughts and feelings leading up to the behaviour (Reference Tyler and GannonTyler and Gannon, 2021). In turn, common subtypes or pathways to offending can be identified based on overlapping features. The first such pathway was developed by Reference Tyler, Gannon, Lockerbie, King, Dickens and De BurcaTyler et al. (2013) who identified three common pathways to offending based on fire-related factors in childhood: the onset of a mental disorder, the level of planning of the fire and whether the individual stayed to watch the fire. These pathways have subsequently been validating in a prison cohort of people with a diagnosed mental disorder (Reference Tyler and GannonTyler and Gannon, 2017). While dynamic pathways provide detailed descriptions of how fire-setting may occur, they are limited to single incidents and tend to be based on small sample sizes (Reference Tyler and GannonTyler and Gannon, 2021).

Functional Analysis: The Only Viable Option Theory

In this model, the ‘Antecedent, Behaviour, Consequence’ (ABC) analysis is applied to recidivistic arson. When antecedents and consequences of arson are such that certain criteria are met, then the behaviour will manifest as ‘the only viable option’ to resolve the situation, viewing it as an adaptive mechanism. Further, Reference Jackson, Glass and HopeJackson et al. (1987) described criteria describing a situation where arson has become pathological. Box 10.6 details the antecedents and consequences identified as well as the factors suggesting pathological fire-setting. Reference Gannon and PinaGannon and Pina (2010) again noted that although the theory is based in social learning theory, there is little empirical evidence to support it, and it lacks explanatory depth.

Box 10.6 Jackson’s Functional Analysis

1. Antecedents

Psychosocial disadvantage (mental illness, intellectual disability, social inadequacy)

Dissatisfaction with life and the self (low self-esteem, depression)

Social ineffectiveness (isolation, poor problem solving)

Specific stimuli (such as previous expose to fire)

Triggers (over which individual may be powerless)

2. Behaviour – Fire-setting behaviour

3. Consequences

Positive reinforcers (attention on the arsonist, financial or political gain)

Negative reinforcers (protection from stressors)

4. Factors indicating pathological fire-setting

Recidivism

Fire setting to property rather than person

Acting alone or repeatedly with an identified accomplice

Evidence of personality, psychiatric or emotional problems

Absence of financial or political gain

Dynamic Behaviour Theory

Reference FinemanFineman’s (1995) model develops Reference Jackson, Glass and HopeJackson et al.’s (1987) model of behavioural analysis to include a number of environmental contingencies, including characteristics of the fire, cognitive factors such as cognitive distortions and feelings before, during and after the fire, as well as triggering events. The model describes a sequence of events leading to the fire with its consequences in several domains.

The Action Systems Model

Reference Fritzon, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonFritzon (2011) applied systems theory to arson and created the ‘Action Systems Model’, which differentiates behaviour according to its origin (i.e. internal or external) and its desired locus of effect (internal or external). This model describes and develops the application of the four modes of functioning (expressive, conservative, integrative and adaptive) based on research in multiple studies (Reference Almond, Duggan, Shine and CanterAlmond et al., 2005). Box 10.7 describes these modes of functioning.

Box 10.7 Action System Model as Applied to Fire-Setting and Arson

| Source of Action | Effect of Action | Mode | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal | Internal | Integrative | e.g. internal distress resulting in fire-setting, self-directed, within own home with suicidal features; often remains at scene |

| Internal | External | Expressive | e.g. exercising power on the external environment, potentially associated with emotional acting out, vicarious attention, remains at scene, often serial offender |

| External | Internal | Conservative | e.g. acts that may arise from external events provoking desire for revenge, remove cause of internal distress, to redress emotional well-being, gain emotional relief, may have witness who may be the main source of distress |

| External | External | Adaptive | e.g. responding to external events and making adjustments to the environment, probably opportunistic, aim to gain or vandalise, cover up another crime |

Reference Miller and FritzonMiller and Fritzon (2007) also demonstrated concordance between the mode of functioning in relation to fire-setting behaviour and self-harming behaviour. Comparison has also been made with the more established and evidenced model for sexual offending (Reference Fritzon, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonFritzon, 2011). Overall, the Action Systems Model is evolving and gradually developing an evidence base to support a unifying explanatory theory for fire-setting behaviour that has the potential to incorporate findings from other models and typologies. In so doing, it also forms a basis on which to begin to assess risk and to identify and direct potential treatment modalities. We would encourage any clinician who encounters fire-setting behaviour and wishes to gain a greater understanding of the individual motivation to familiarise themselves with this model.

Multi-Trajectory Theory of Adult Fire-Setting (M-TTAF)

This theory by Gannon et al. extended the work of Fineman into a unified, two-tiered, multifactor theory (Reference Gannon, Ó Ciardha, Doley and AlleyneGannon et al., 2012). This included an aetiological framework that considered how developmental factors can lead to psychological vulnerabilities that predispose an individual to fire-setting. It also considers the triggers and moderating factors and how these interact with psychological vulnerabilities to become critical risk factors that ultimately increase the risk of fire-setting. The M-TTAF then goes on to describe five subtypes or trajectories towards fire-setting based on the aforementioned characteristics: antisocial, grievance, fire interest, emotionally expressive/need for recognition and multifaceted. We direct readers to the work of Reference Gannon, Ó Ciardha, Doley and AlleyneGannon et al. (2012) and Reference Tyler and GannonTyler and Gannon (2021) for further reading on this theory.

Clinical and Risk Assessment of Fire-Setting

The clinical and risk assessment of fire-setters is not straightforward due to a variety of reasons, not least of which is a lack of research and the absence of a structured, validated arson-specific risk assessment tool.

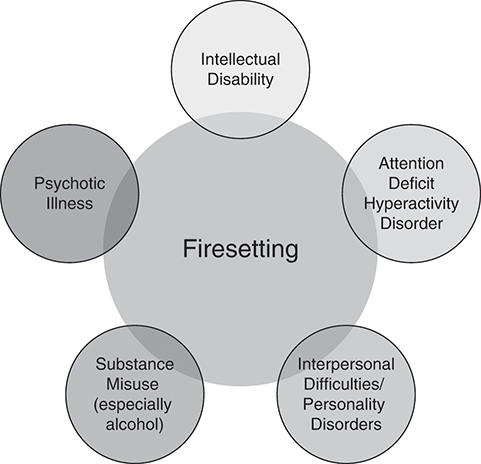

Diagnostic Considerations

As detailed earlier in this chapter, there is an emerging picture of fire-setting behaviour being associated with poor impulse control. Many mental disorders are associated with poor impulse control as a core feature of their psychopathology and behavioural disturbance. Psychosis, intellectual disability, autistic spectrum disorders, substance misuse disorder (especially alcohol) and personality disorders have been noted as having a stronger association with fire-setting within forensic populations (Figure 10.1). Specialist assessment of intellectual functioning or screening for autistic spectrum disorder may be less common in the general inpatient setting but should be borne in mind along the assessment pathway in those with fire-setting behaviours. There has been some association identified between fire-setting and ADHD in childhood (Reference Johnson and NethertonJohnson and Netherton, 2016). Although there is no data currently available for adults, given the association with impulsivity that is emerging in other avenues of fire-setting research, it may reasonably be speculated that adult ADHD may be similarly associated with this type of offending, as is becoming clear in other types of offending behaviour (Reference Young and ThomeYoung and Thome, 2011).

Figure 10.1 Mental health diagnoses associated with fire-setting behaviour

Substance Misuse

Any individual who demonstrates fire-setting behaviour or risk factors should be carefully assessed for concomitant substance misuse problems. In particular, alcohol misuse has been found to have a high prevalence in several studies (Reference Lindberg, Holi, Tani and VirkkunenLindberg et al., 2005, Reference Blanco, Alegría, Petry, Grant, Simpson and LiuBlanco et al., 2010) as well as in female fire-setters (Reference LinakerLinaker, 2000). Consideration should be given to referring to a dual-diagnosis service or substance misuse liaison where available.

Personality Assessment

Concomitant assessment of personality using a semi-structured tool such as the International Personality Disorder Examination (IPDE) (Reference Loranger, Sartorius, Andreoli, Berger, Buchheim and ChannabasavannaLoranger et al., 1994) may provide helpful information, allowing further insight into the relational aspects of fire-setting behaviour in an individual in the context of their personality structure; for example, anti-social personality traits or disorder are known to be associated with increased risk of fire-setting (Reference Blanco, Alegría, Petry, Grant, Simpson and LiuBlanco et al., 2010), and characteristics of self-harm behaviour in women with personality disorder may indicate the action systems type which may be manifest in a potential fire-setter. The importance of interpersonal inadequacy in the fire-setting population is well established (Reference Lewish and YarnellLewis and Yarnell, 1951, Reference RixRix, 1994), and there has been considerable discussion of the role of individuals who are unable to effect change through socially acceptable means, using fire as a vehicle for this (Reference StewartStewart, 1993).

Other Areas

Impulsivity, anger, psychopathy and cognitive distortions are areas which are considered by expert consensus to be relevant in the risk assessment of fire-setting, although as yet there remains little robust evidence (Reference Doley, Watt, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonDoley and Watt, 2011). Impulsivity plays a role in various theories of antisocial behaviour but has not been specifically characterised in relation to fire-setting. In contrast, anger has been identified as a precursor to fire-setting, potentially as a disinhibiting factor as in its association with violence. Cognitive distortions describing offender relationships with antisocial attitudes and justifications for offending behaviour are well characterised in a diverse range of offending, particularly sexual offending, and have been postulated to impact on the employment of empathy. Psychopathy, however, reflecting amongst other things a stable combination of persistent irresponsible behaviour, lack of empathy and deceitful behaviour, has not shown significant differences between arsonists and non-arsonists in a high-secure population (Reference Labree, Nijman, Van Marle and RassinLabree et al., 2010) nor have psychopathic traits been associated with fire-setting recidivism (Reference Thomson, Tiihonen, Miettunen, Sailas, Virkkunen and LindbergThomson et al., 2015).

Assessment of Risk of Fire-Setting in Mental Disorder

It may not be immediately obvious, or even known, if there is a history of fire-setting behaviour. It is clearly important in such patients to establish the presence or absence of a history from the outset. In this case, an initial approach may simply involve asking one or two questions to make an assessment. Questions investigating whether they have or have ever had any thoughts or history of using fire to harm themselves or others, or whether they have ever engaged in any fire-play as a teenager or adult, may be a starting point. Positive answers to questioning of this nature should prompt more in-depth inquiry as to the specific circumstances, motivations, emotions, number of incidents, consequences, criminal justice involvement and other factors previously described in obtaining a clear picture of the behaviour. If concerns are raised, these should be further investigated, as we discuss later in the chapter.

Some patients may present with an already known history of fire-setting behaviour or arson convictions. Such patients should immediately prompt a detailed past and recent history and mental state examination characterising the fire-setting behaviour. Similarly, any known history of fire interest in the past, either in the community or during previous admissions, threats or behaviour forming part of the circumstances of the current admission, nursing staff noting some concerning behaviour relating to lighters or threats to burn others whilst on the ward indicates detailed investigation. Collateral sources of information should be obtained where possible, including from the police and criminal justice system where relevant, and in accordance with appropriate information sharing arrangements. History of fire interest from a developmental and adult perspective should be obtained, identifying any deviant or pathological patterns of concern.

In assessing the risk of fire-setting in the inpatient setting (and indeed other forms of violence), validated structured assessment tools should be used. At present, there is no specific tool to assess risk of fire-setting in the mentally disordered population. In the absence of such a tool, the inpatient clinician is directed to the HCR-20 (Reference Guy, Wilson, Douglas, Hart, Webster and BelfrageGuy et al., 2013), which is validated as a structured risk assessment tool in mentally disordered populations. The main clinical utility of this tool is to assist in forming an overall impression of risk in the criteria of ‘low’, ‘moderate’ and ‘high’ based on characterising static and dynamic risk factors (scored as absent, unknown, partially/possibly present or definitely present), allowing scenario planning to anticipate situations where risk may be increased and to identify strategies to reduce the risk. Clinicians should consider applying the concepts described in Box 10.7 when populating the risk assessment to allow identification and formulation of the patient’s fire-setting behaviour in the context of the action systems framework. It is recommended that such an assessment be carried out in a multidisciplinary fashion by staff who have received appropriate training. There may be benefit in also obtaining a forensic psychiatric opinion for a variety of reasons, including to support the risk assessment, to provide a specialist opinion regarding care pathway and to advise on any outstanding medicolegal issues, for example.

There are several useful tools that may be employed for characterising a variety of factors relating to fire interests and fire attitudes in a patient. These are the Fire Interest Rating Scale (FIRS) and the Firesetting Assessment Schedule (FAS). The FIRS provides 14 descriptions of fire-related situations and the subject self-rates on a seven-point Likert scale how the scenario makes them feel, ranging from ‘most upsetting’ to ‘very exciting’. The FAS provides 32 statements, 16 that relate to cognitions and feelings prior to a fire and 16 that relate to feelings post fire, that the person rates as ‘never’, ‘sometimes’, or ‘usually’. These have also been used for individuals with an intellectual disability (Reference Murphy and ClareMurphy and Clare, 1996). The Fire Attitude Scale is a 20-item task that examines the respondent’s attitudes to fire in different contexts to provide an overall attitude score, whereby higher scores indicate more problematic attitudes towards fire-setting (Reference MuckleyMuckley, 1997).

Reference Ó Ciardha, Barnoux, Alleyne, Tyler, Mozova and GannonÓ Ciardha et al. (2015a, Reference Ó Ciardha, Tyler and Gannon2015b) have since developed the Four Factor Fire Scales focusing on the concepts of identification with fire, serious fire interest, poor fire safety and fire-setting as normal. These scales have proven to be more effective than the aforementioned scoring systems in adequately discriminating between fire-setting and non-fire-setting individuals.

It also remains unclear as to what proportion of individuals will reoffend through fire-setting. A recent meta-analysis investigating this found that 57%–66% of fire-setters would reoffend in some way, with 20% engaging in deliberate fire-setting. The odds of future fire-setting were fivefold greater for those with a known history of fire-setting compared with other offenders (Reference Sambrooks, Olver, Pag and GannonSambrooks et al., 2021). However, there was significant variability and heterogeneity between samples, follow-up periods and definitions of reoffending, indicative of the urgent need for more research in this area.

Reporting of Threats or Fires

From a practical perspective, it is the authors’ view that any incidents such as threats made by a patient to harm an individual or organisation through the use of fire or actual setting of fires on a ward should be taken extremely seriously and prompt a report to the police, who can take forward any criminal investigation as appropriate. As described earlier, the setting of fires in hospitals is not unknown, and attendance at psychiatric hospitals by the Fire Service as compared to general hospitals (one in three callouts to hospital) is disproportionately represented in terms of the number of beds (20% of all National Health Service [NHS] beds). There have also been a number of major fires in recent years at NHS and private hospitals which could have resulted in (although fortunately did not) loss of life (Reference Grice, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonGrice, 2011).

Risk Management Strategies in Inpatient Settings

The risk management of those who set fires when presenting to an inpatient setting will, in many respects, be guided by the risk assessment and the types of concurrent risk behaviours with which the individual is presenting. Active mental disorder and associated behavioural disturbance should be managed on a case-by-case basis using established inpatient risk management and treatment modalities. Without providing an exhaustive list, these will include pharmacological treatment of any active mental disorder and behavioural disturbance, supportive nursing care, with consideration of low-stimulus environment, or extra-care areas (ECAs) where available. If behavioural disturbance is not responsive to de-escalation, then consideration should be given to the need for additional tranquilisation, including intramuscular medication and supervised confinement. However, the important principle to bear in mind is that the risk of fire-setting is elevated in such individuals, particularly in the context where impulsivity may be enhanced, such as following an argument with staff or another patient, in the context of active psychosis or threats of self-harm. Specific risk management strategies can be used to reduce the risk of a fire occurring; many of these are common sense, and we outline some suggestions in Box 10.8.

Box 10.8 Suggested Practical Risk Management Strategies Specific to Fire-Setting

Ensure that there are clear procedures and rules regarding fire-setting threats and behaviours, and that boundaries are known to patients and are adhered to.

Ensure fire detection and safety equipment and fire safety procedures are known to staff.

Take any threats to make a fire seriously and consider this an opportunity to engage with a patient to obtain further information to inform the risk assessment.

Pay close attention to the circulation of lighters or matches on the ward (count required), particularly at smoking times. Consider enhanced staff presence at these times.

Be aware of accelerants being obtained or secreted (e.g. wax crayons, soap bars, tissue paper) and whether these are present on the ward.

Consider whether 1:1 observations are appropriate if risk is escalating.

Consider whether the physical, procedural and relational security of the ward is sufficient to manage the risk.

The Treatment of Fire-Setters

At a fundamental level, given that fire-setting is not associated with a specific disorder, assessment and treatment of any underlying disorder should be the main thrust for patients presenting in an inpatient setting. Clearly, this will be dependent on the nature of the diagnosis reached in the first instance and the concomitant gathering of information obtained throughout the admission, including behaviour related to observed fire-setting. However, in terms of specific specialised fire-setting therapy, there is very little evidence-based intervention to offer beyond an educational approach.

Education

In the inpatient setting, there may be an opportunity to provide basic education concerning fire risk and enable the acquisition of fire safety skills. Although this may not be immediately feasible in the inpatient setting, it should be flagged and signposted along the care pathway for further development. Even a brief home visit by a firefighter may be of benefit. Evidence for the efficacy of this has come from juvenile populations (Reference Hollin, Dickens, Sugarman and GannonHollin, 2011).

Group Work

There have been several statistically low-powered studies which have attempted to evaluate specific group therapy with mentally disordered offenders who set fires with evaluation using the FAS and FIRS. There is very little robust data to demonstrate efficacy, although the targets for development through this work include developing coping skills and self-esteem, increasing understanding of risks and developing personalised relapse prevention plans along a cognitive behavioural model.

Reference Gannon, Alleyne, Butler, Danby, Kapoor and LovellGannon et al. (2015) conducted a non-randomised trial of 54 male prisoners who had deliberately set fires and were enrolled in a standardised cognitive behavioural therapy group to specifically target this behaviour. This was shown to improve measures of problematic fire interest and associations with fire at three-month follow-up as measured through the Fire Factor Scale (Reference Ó Ciardha, Barnoux, Alleyne, Tyler, Mozova and GannonÓ Ciardha et al., 2015a). While robust long-term outcome data remains to be seen, such specialist treatments may be of benefit to those with the most serious fire-setting behaviour.

Pharmacotherapy

The use of pharmacotherapy in treating fire-setting behaviour is extremely poorly understood. To our knowledge, there have been no clinical trials or other studies to evaluate the benefit (or harm) of specific pharmacological agents. Reference Parks, Green, Girgis, Hunter, Woodruff and SpenceParks et al. (2005) reported a case study of pyromania in a homeless person responding to treatment with olanzapine; and given the emerging picture of impulse control being an important factor, medications that are known to have this effect in other forms of behaviour may be of benefit (Reference Pallanti, Quercioli, Sood and HollanderPallanti et al., 2002). Further research is urgently needed in this area.

Care Pathway Considerations

The care pathway for fire-setters in the inpatient (non-forensic) setting will depend upon several factors including, for example, the presence of active mental disorder, response to treatment with medication of underlying mental disorder, comorbidity of mental disorder or active substance misuse and severity of behavioural disturbance. The care pathway should be additionally informed from the structured risk assessment and assessment of personality.

Figure 10.2 shows a proposed process to guide the assessment of individuals admitted to hospital with an identified or known risk of fire-setting or arson. Owing to the absence of a clinically validated tool to assess arson risk, this is subject to individual clinical experience with working with this patient group and using clinical judgement incorporating the information obtained through assessment. Specialist support and assessment from a forensic psychiatrist should be considered at an early stage, and ongoing liaison maintained throughout the assessment and treatment, particularly where there are changes or escalation in presentation with relation to fire-setting behaviour. This may include threats made, actual fires set or the bringing of criminal charges.

Figure 10.2 Suggested process for assessment and care pathways for fire-setting in inpatient units

Consideration of whether the level of security is appropriate should remain under constant review. The availability of appropriate treatment from a psychological perspective may not be available in the non-forensic setting, and this should be incorporated into care pathway decisions, again in consultation with forensic psychiatric services where such treatment is available. The involvement of the patient with criminal justice or probation services may also be relevant, and this may be a care pathway through which access to treatment may be achieved, whether in a hospital, custodial or community setting, again informed by the risk assessment and broader clinical presentation.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we provided an overview of some of the core knowledge and clinical aspects which we consider to be of importance in the clinical and risk assessment of patients who present with fire-setting behaviour or histories. Key points for the busy clinician to use should they encounter fire-setting behaviour in their patient group include:

Fire-setting behaviour in mental health populations is more common than in the general population, although a robust evidence base to quantify specific associations is not yet developed. It is likely that the inpatient clinician will encounter patients with fire-setting behaviour with some frequency.

There is emerging evidence to suggest that poor impulse control may be associated with fire-setting behaviour in relation to mental disorder and mental illness. In forensic populations, there are associations between fire-setting and psychosis, autistic spectrum disorder, intellectual disability, substance misuse and interpersonal inadequacy.

An emerging explanatory theory uses systems theory as applied to fire-setting to describe the source and effect of the behaviour.

The risk of fire-setting should be taken seriously by any clinician. It is important to screen and, if identified, investigate in detail where evidence of historic or recent fire-setting behaviour or arson are found.

Since there are no structured risk assessment tools currently available specifically for fire-setting, the use of the HCR-20 is recommended, with forensic input if considered appropriate. Even when fire-setting behaviour is not identified, this should be kept under review owing to the associations with mental disorder.

Clinicians encountering fire-setting behaviour in patients should combine careful clinical diagnosis, response to treatment and risk assessment in the identification of an appropriate care pathway, and liaison with forensic services should occur where more specialised treatment may be available. This may include greater therapeutic physical, procedural and relational security. We propose a care pathway to guide clinicians through this process.

There is limited information on the effectiveness of psychological treatment interventions, which include cognitive behavioural therapy and educational individual and group work.

The ground is fertile for clinicians to contribute to the evidence of fire-setting in the context of mental health in terms of epidemiology, diagnostic associations, response to pharmacological treatments and formulation of care pathways.

*This chapter originally appeared as a paper in the Journal of Psychiatric Intensive Care (Reference Hillier, Cherukuru and SethiHillier et al., 2015). It has been updated and adapted for publication in this book.