Book contents

- Rome, China, and the Barbarians

- Rome, China, and the Barbarians

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Maps

- Acknowledgments

- A Note to the Reader

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Ethnography in the Classical Age

- Chapter 2 The Barbarian and Barbarian Antitheses

- Chapter 3 Ethnography in a Post-Classical Age

- Chapter 4 New Emperors and Ethnographic Clothes

- Chapter 5 The Confluence of Ethnographic Discourse and Political Legitimacy

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

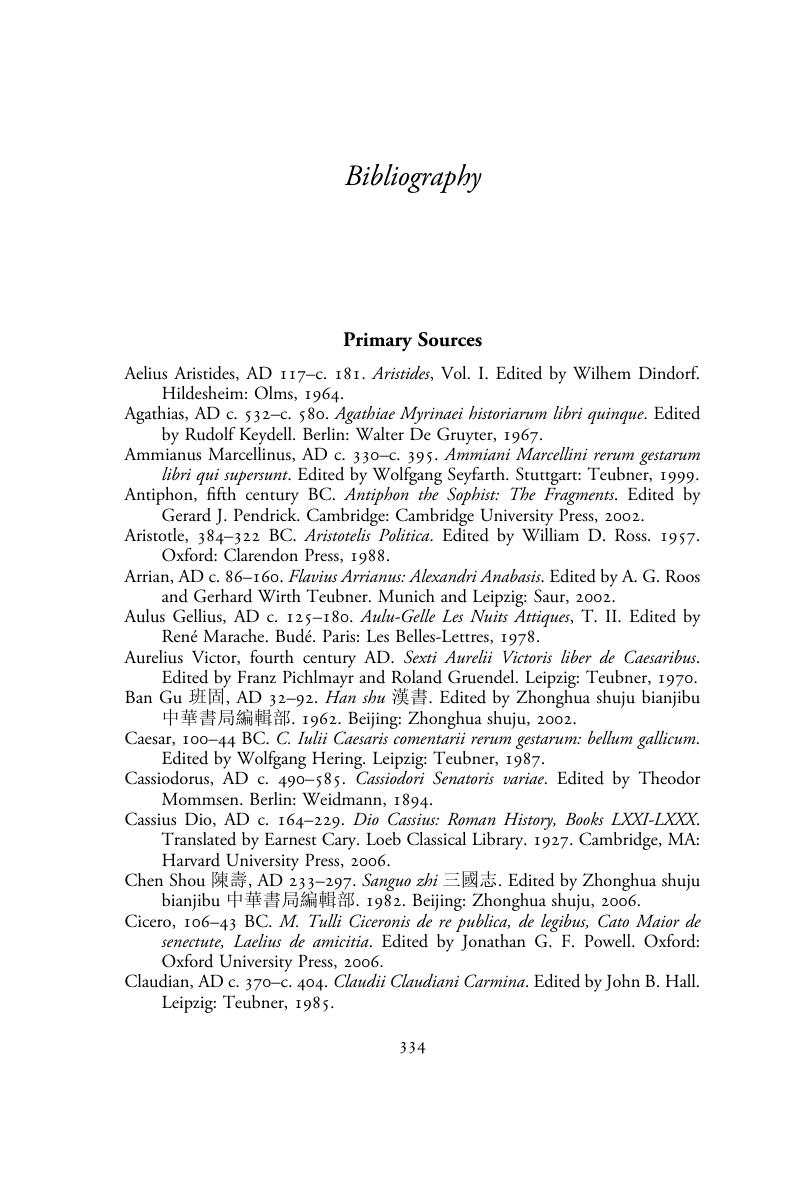

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 April 2020

- Rome, China, and the Barbarians

- Rome, China, and the Barbarians

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Maps

- Acknowledgments

- A Note to the Reader

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Ethnography in the Classical Age

- Chapter 2 The Barbarian and Barbarian Antitheses

- Chapter 3 Ethnography in a Post-Classical Age

- Chapter 4 New Emperors and Ethnographic Clothes

- Chapter 5 The Confluence of Ethnographic Discourse and Political Legitimacy

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Rome, China, and the BarbariansEthnographic Traditions and the Transformation of Empires, pp. 334 - 358Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020