Book contents

- Shell Shock, Memory, and the Novel in the Wake of World War I

- Shell Shock, Memory, and the Novel in the Wake of World War I

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Book part

- Introduction Shell Shock and the World War I Novel

- Part I Invisible Wounds and Narrative Returns

- Part II Fractured Identities and Forgotten Histories

- Part III Troubling Men and Memorial Fictions

- Notes

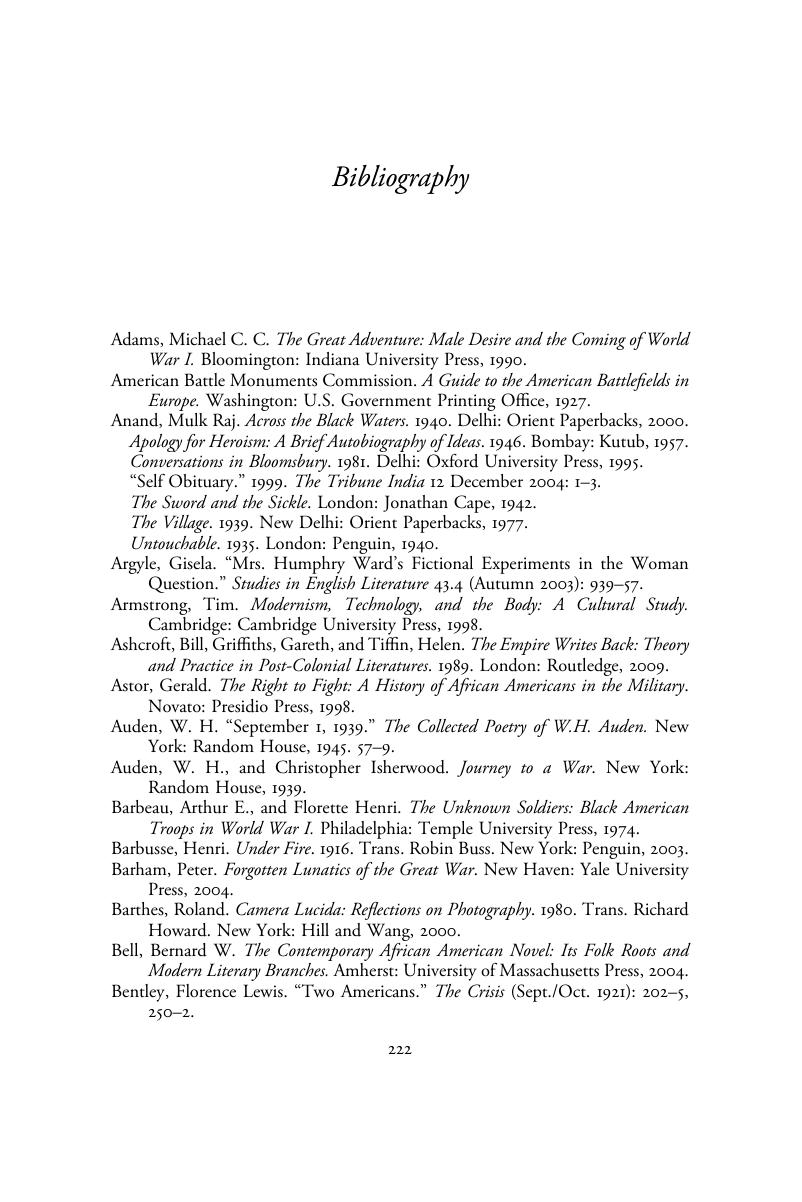

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2015

- Shell Shock, Memory, and the Novel in the Wake of World War I

- Shell Shock, Memory, and the Novel in the Wake of World War I

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Book part

- Introduction Shell Shock and the World War I Novel

- Part I Invisible Wounds and Narrative Returns

- Part II Fractured Identities and Forgotten Histories

- Part III Troubling Men and Memorial Fictions

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Shell Shock, Memory, and the Novel in the Wake of World War I , pp. 222 - 240Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2015