The most famous speech in American jurisprudence strode into the lecture hall without title or name. Prominent members of the profession had gathered on an overcast Friday afternoon to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Boston University School of Law. The clock soon struck half past two. Slated to deliver the keynote address, the tall, handsomely attired man with the imposing soldier’s mustache silently sat back, expressionless perhaps, and waited his turn at the podium as encomia and pieties plied the thick air.Footnote 1

The School’s honored former professors, oblivious to the passing minutes, quietly contemplated the ceremony from portraits hung on freshly painted, cream-colored walls.Footnote 2

The celebration featured a dedication for a new hall, Isaac Rich Hall, where the event took place. The hall occupied the top floor of a building recently bought and renovated; Bostonians had for fifty years called it the Mt. Vernon Church. The renovators kept the grand classical Greek façade and redid most everything else. The revamped upstairs space now filled with law students, faculty, and distinguished guests, including the presidents of Harvard and Tufts and the dean of the Harvard Law School.Footnote 3

According to the Boston Evening Transcript, attendees took careful note of Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Associate Justice Holmes’s address. Holmes himself later remarked that he had sleepy eyes pretty much wide-awake after he began.Footnote 4 He probably had good reason to be self-congratulatory since before he stood and addressed the audience the second of three scheduled speakers, a prominent alumnus, William V. Kellen, former Reporter for the Supreme Judicial Court, recounted in lengthy detail the history of the School of Law and its teaching methods.Footnote 5

Mr. Kellen’s programmatic discourse on the evils of an impoverished legal education – which included his lauding the merits of a sequenced curriculum “tied to no [pedagogical] system” that required the passing of “due test examination” before the pupil could advance to a degree – managed to adroitly sidestep acknowledging the School’s debt to Christopher Columbus Langdell, Harvard Law School’s renowned former dean.Footnote 6 At the same time it nicely continued the School of Law’s heritage of protest – of using for instruction “every known method, device, and appliance” – against Langdell’s ignominious single-minded “case method,”Footnote 7 even if the passing of years and the making of casebooks had subdued the protest’s once impassioned resolve.

Dean Langdell, who began teaching at Harvard Law School in 1870, pioneered both the “case method” and the new graduation requirements for those Kellen called “embryo lawyers,” the future “advisers to clients” and “assistants to juries and judges.” They had to study for longer terms and pursue a sequenced program of courses. A student also had to pass examinations in each year’s courses before advancing to the succeeding year or obtaining a degree. But Boston’s, not Harvard’s, had been the first law school in the country to extend formally the term of study to three years, a fact the speaker did not shy away from pointing out in 1897.Footnote 8

The case method of instruction Langdell first wrought upon Harvard’s law students eventually found literary notoriety in a fine and funny novel, The Paper Chase, published 100 years after the start of Langdell’s tenure.Footnote 9 The Paper Chase also inspired an equally well-regarded movie and television series of the same name. The schooling of lawyers had by then become the country’s most infamous rite of passage into an established profession.

The revolt against Langdell began from the beginning. His lampooned case method added incentive for Boston University to open its School of Law in 1872. It welcomed into its inaugural class disgruntled law students who sought refuge from what a later historian dubbed “Harvard’s insanity.”Footnote 10 Former Reporter Kellen graduated in 1876.Footnote 11

The Transcript correspondent for the January 8, 1897 event made no mention of these hidden skirmishes. He dutifully devoted a few column inches to Kellen’s solemn recital of the School of Law’s accumulated glories before providing a remarkably accurate summary of the featured address. Holmes’s address, the reporter once again prefaced, was “followed with the closest attention by the distinguished assemblage.”Footnote 12

The study of the law is the study of the means of predicting cases in which the public force will be brought to bear upon the person concerned. The general propositions of the law, the so-called legal rights and duties, are only prophecies as to such cases. It is well to look at the subject from the point of view of the bad man who cares only for the practical consequences of his conduct. In this way we avoid one of the great fallacies which beset the subject – the confusion between law and morals – or between law and what we think ought to be the law. This confusion is felt in the common reasoning as to the rights of man, and as to the nature of duty in the legal sense.

Thus reads the opening paragraph of one newspaper’s report to the Boston community of what Holmes said. In hindsight this paragraph, especially its first sentence, captured the gist of the opening sections of Holmes’s address better than many subsequent full-length articles. The reasons for the disparities in comprehension are as curious as they are opaque.

Certainly Holmes must bear some of the fault himself. He sent his address into the world without a title.Footnote 13 Upon publication, both in this country and abroad, the nameless discourse assumed various guises. Boston University first published it as a pamphlet with the not very eye-catching title, “Address Delivered at the Dedication of the New Hall of the Boston University School of Law, January 8, 1897.”Footnote 14 Students at the School of Law published the address the following February in the Boston Law School Magazine. They anointed it, “The Path of the Law.”Footnote 15 The Harvard Law Review used the same name when it published the piece in March 1897.Footnote 16

Scotland’s prestigious Juridical Review also published it in 1897, but anonymously and under a different title: “Law and the Study of Law.” It advised its readers in a footnote that “[t]his discourse was pronounced at the dedication of the New Hall of the Boston University School of Law on 8th January, 1897. The author has kindly consented to its publication in the Juridical Review.”Footnote 17

When preparing the address, Holmes had variously referred to it as a discourse on “Legal Education,” “The Principles of Legal Study,” or “The Theory of Legal Study.”Footnote 18 Given how Holmes described the address, one would expect to find among the reams of articles devoted to interpreting, critiquing, praising, or damning “The Path of the Law” – especially its infamous homunculus, the bad man – or among those simply using the piece as a foil for the scholar’s analytical virtuosity or philosophical commitments, at least a significant subset devoted to the more mundane task of explicating the theory of legal study expressed within it. But no, that expectation would be disappointed.

“The Path of the Law” may be esoteric but cryptic it is not. The address itself did not hide Holmes’s intent. One prominent commentator, considering an interpretation that cut across conventional lines, weighed the possibility that the “speech delivered to law students, is not about how to practice law, but how to study law.” He further noted: “The first four words are ‘When we study law,’ and Holmes reminds us of his topic no fewer than ten times.”Footnote 19 Despite this auspicious start, the commentator declined to pursue this line of inquiry.Footnote 20

Of the numerous articles by contemporary legal scholars that have discussed or dissected “The Path of the Law,” only William Twining in a pair of pieces separated by almost twenty-five years has persisted in the contention that “The Path of the Law” is not a “contribution to general jurisprudence, it was intended first and foremost as a discussion of legal education.”Footnote 21

Part of the purpose of this book is to continue along the course that Twining first took. I also recognize Hessel Yntema as a forerunner. Yntema in his 1931 “Mr. Justice Holmes’ View of Legal Science” expressly identified “The Path of the Law” as containing “canons of dogmatic study,” that directly connected to Holmes’s theory of legal history and his scientific ideal.Footnote 22 Regrettably, Twining does not attempt to connect Yntema’s insights with his own. Yet Yntema took an intriguing tack, and in like manner I will also try to bring the different sections of “The Path of the Law” – which Twining described as diffuse and rambling, filled with aperçus and obiter dictaFootnote 23 – into a tolerable working relationship. I do not contest Twining’s observation that “Holmes never worked out in detail the implications of his pronouncements on legal education.”Footnote 24 And only demur from Twining’s contention that Holmes’s “prescriptions were scattered and vague, and he dropped only a few very general hints about his view on educational priorities.”Footnote 25

Twining also suggested that Holmes in “The Path of the Law” put forth an “alternative philosophy of legal education to that which was prevailing at the time[.]”Footnote 26 Twining believes this alternative philosophy to be proto-realist and that Holmes probably did not realize the tremendous difficulties involved in implementing his suggested approach. Again, while I believe Twining to be on the right track I go in a different direction. My objective in this book, though, is not merely to point out how Twining got it wrong, or less than right, or how others missed the boat entirely, but to tackle some fundamental questions about “The Path of the Law.” If Holmes’s most famous discourse contained, at least in his mind, the rudiments of a theory of legal education then it seems to me worthwhile to inquire deeply into the subject.

In 1973 Twining made an interesting comment:

Although the main focus of “The Path of the Law” is on legal education, it does not follow that the significance of the piece is limited to that relatively parochial topic. Worthwhile discussions of legal education often lead directly to the questioning of accepted theoretical assumptions, and Holmes’s address is not a unique example of provocative jurisprudential statements stimulated by educational concerns. There has been, especially in America, a close connection, both historical and analytical, between legal theory and legal education.Footnote 27

I happen to think legal education a less parochial topic than Twining did when he wrote this paragraph. The ways aspiring lawyers are brought into the profession in the United States has clearly discernible consequences for the practice of law, the quality of the legal system, and for the social bonds that underwrite both the practice and the system. How to understand those social bonds is a question of the utmost importance. But, as Holmes often liked to say, let’s not get the cart before the horse.

This book seeks to make a contribution to both American legal history and legal theory. It seeks to build on Twining’s comment that in the United States there is a close connection, both historical and analytical, between legal theory and legal education. My basic argument, in one respect following Yntema, is that Holmes in “The Path of the Law” articulates a theory of legal study that depends upon, in ways not immediately obvious, his previous body of work. And that he further extends his most important insights in an essay that came two years later, “Law in Science and Science in Law.”

Thus, on one level, this book is a work of intellectual history that describes and explicates certain of Holmes’s ideas. But standpoint matters a great deal. My standpoint is that of a practicing lawyer. I think this matters because standpoint orients a discourse. I have also become convinced, after a prolonged immersion in Holmes’s writings, that he shared a similar standpoint, that much of what he wrote he did for the purpose of improving the profession.

Think back for a moment to the Boston University School of Law event. The challenge implicit in a seasoned lawyer and judge addressing a group of budding professionals, the law students in the audience, arises from a disparity in experience. On one side of the podium stands a person well versed in the subject matter and practiced in its employment. On the other side sit novices. How does one convey to these students important lessons of professional experience in a manner pithy and memorable? How does one describe the professional path they ought to take?

Holmes rose to the challenge by crystallizing his convictions – he had, as of 1897, spent over thirty years in the profession, as student, practitioner, scholar, professor, and judge – and by conveying them in a style best described as the opposite of cant. “The Path of the Law” is not an exercise in plain speaking. It is too compressed for that description to work. Yet neither is it overly formal and sententious, in the style one might expect of a typical nineteenth-century vocational address. It conjoins the realism of hardened expectation with a hint of revelatory exclamation; it exhibits a distinctive habit of mind, a novel way of taking and talking about legal issues. My interpretation of “The Path of the Law” is premised on the belief that its rhythm, cadence, and movements match the vibrancy of a life lived in law as law existed in Boston (and probably beyond Boston) in the final quarter of the nineteenth century. It is also premised on the conviction that Holmes sought to rise a bit above that life, his here-and-now, not to repudiate it, but to give philosophical expression and extension to the vibrancy.

The most important sentence in “The Path of the Law” is the first: “When we study law we are not studying a mystery but a well known profession.”Footnote 28 Throughout the address it stays visible, often a wavering watery image hovering in the distance to be sure, but no matter where in the text the reader is this sentence makes its presence felt. “When we study law we are not studying a mystery but a well known profession.” The sentence seems latched; it’s not. It begs a series of questions: why do we study “law” and not “the law”? To whom would it occur to say law is a mystery? And this profession the law student studies when he or she studies law – for what is it well known? Are we talking about members of America’s so-called aristocratic class – as Tocqueville referred to the legal profession in the nineteenth century – or a collection of “pettifoggers and vipers,” a long-lived description of legal practitioners in Anglo-American history? Or both? The questions the first sentence elicits are ranging but the point in focus is not. The center of attention, as the address reveals, is the what, how, and why of legal study.

Holmes also sought to encourage his established colleagues in the audience (the practicing lawyers and law professors) to employ a more refined, disciplined intelligence in resolving society’s disputes and assisting in its ordering than that employed by those who had not taken the path of the law. If students of law aspired to be more than practitioners of a trade or members of an occupation – if law itself were to mature into a productive discipline – it demanded the development of certain skills. These included the twin abilities to understand the ends law had served in the past, and to use that nuanced awareness of past ends to formulate the necessary inquiries to ground future law.

As a judge, Holmes preferred to view current legal issues in a manner that respected the present course of the law. Yet he also wanted other members of the profession to share his interest in visualizing alternative directions, maybe even comparing new wants to past ends long forgotten. He also encouraged, as many people have pointed out, a more realistic or scientific approach to society and its problems. Holmes valued what his predecessors in the profession had accomplished – as befitting a jurist who authored a classic text on the common law – but he shied away from giving them too much credit. Though he never said it, he seems to have drawn a lesson from the unstated fact that law, unlike other inspired intellectual and artistic endeavors in the ancient world, had no recognized muse.Footnote 29 It drew its inspiration from sources less divine.

This study, then, as a work of intellectual history, will take the liberty of bringing into the twenty-first century a message intended for the twentieth. It takes its stand on my belief that Holmes intended “The Path of the Law” to be a primer on legal education. For that supposition to work successfully one must re-envision “The Path of the Law” against the backdrop of Holmes’s pre-1897 jurisprudential and extra-jurisprudential writings. One must look carefully at The Common Law and the articles that came before and after it. One must ponder the collection of addresses contained in his Speeches. The majority of the forthcoming pages will focus on bringing to the fore and clarifying the cardinal ideas that ultimately find articulation in “The Path of the Law” and Holmes’s later article “Law in Science and Science in Law.” Though we will comment on these pieces along the way, they will not receive their fullest exposition until the last part of the book, Part V. In true Holmesian fashion we will seek to discern the pathways of thought from which “The Path of the Law” itself emerged and the direction toward which it tends.

The effort to discern and articulate the direction of Holmes’s jurisprudential thinking that goes beyond “The Path of the Law” serves as the second aim of this book. In this respect the book moves from intellectual history toward legal theory. It seeks to build on Holmes’s work, to articulate a theoretical foundation for legal education. One that ties teaching and learning to practice, practice to scholarship, and scales each of these endeavors according to their avowed purpose. That avowed purpose I take to be perfecting professional judgment.

Holmes had a unified sense of life that enabled him to grasp law as a purposive social activity.Footnote 30 The activity of law – its self-conceptualizations, its procedures and doctrines, its self-understood aims and justifications – has its own history within the broader culture. This study proposes that Holmes looked ahead toward a time when law would undergo a paradigm shift. I do not see that paradigm shift as the supersession of law.Footnote 31 Instead, I see it as dissolution of law’s traditional conceptual architectures. That will fully happen when sufficient legal professionals in this country recognize the importance of law’s three-dimensionality. Once they become adept at viewing law in this manner they may be able to construct, from that standpoint, a usable metric of the law. This task of constructing a metric is not easy to describe. It is not simply a matter of selecting one feature of experience – utility, for example – and using it to measure or gauge all other aspects. For now, let me just say that construction depends on a three-dimensional perspective. It will require legal professionals to determine the best means to coordinate various dimensions of American experience (such as sequence and context), and map certain features (such as specific iterations of liberty or equality) that once found, or continue to find, expression in and through law.

Viewing American law in three dimensions is such a counterintuitive notion I should try to explain what I mean. Especially since much of the following exposition is an extended effort to both clarify (the intellectual history part) and extend (the legal theory part) Holmes’s work by showcasing this one idea. And, as I will shortly discuss, the book’s structure also contributes to the development of this idea by laying the analytical and historical framework necessary to bring “The Path of the Law” into 3D. We go from initial static delineations in the early parts to subsequent depictions that have increased dynamism and directionality.

For the purposes of legal pedagogy, teaching a student to view law in three dimensions means that the student must enter into what Holmes called “the purely legal point of view.” The spatial imagery is important to our purposes because knowing one’s way around law proper – as one tacitly knows one’s way around one’s hometown or neighborhood – leads to better-informed, on-point decision-making. To say it another way, professional knowledge and personal knowledge must be deliberately tied into each other so professional judgment may grow and mature.

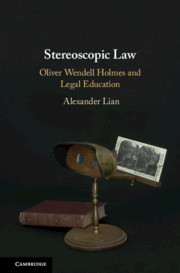

Most of us, unassisted, cannot view law in three dimensions. We need to enhance our natural and acquired capabilities with artificial aids. To emphasize the point I have chosen to put on the cover of this book a photograph of a hand-held stereoscope that Holmes’s father, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr., invented, but did not patent, in 1859. The replica I was able to find on eBay sits on a small stand. The plate on the stand’s base identifies the viewer as “THE HOLMES STEREOSCOPE.”Footnote 32

A stereoscope is a device that mechanically reproduces what the human eyes do naturally. It takes two individual images, both similar but not identical, and merges them together to create a three-dimensional image. It artificially creates depth within a visual field. The resulting image is a tertium quid, a third something, that brings together into harmony two distinct photographic images. Two Holmes sentences first alerted me how I, as a practicing attorney, saw law – as I had been taught to see it – was shockingly superficial, flat.

When I began it was not so easy as it is now to see that law, looked at through the stereoscope of history, is the story of our growth. It was not easy to put to oneself even the vaguer proposition that as the facts of the law are facts of the universe they are worthy of their share of the only intellectual interest there is, – the interest of being seen in their universal relations.Footnote 33

These two sentences do much to bring Holmes’s intellectual life into focus. They are from an unpublished and provisional farewell address he gave at the Boston Tavern Club after being nominated to the United States Supreme Court but before confirmation. In this after-dinner speech he eloquently, insightfully, but circumspectly commented on the life education he had received from over sixty years of living in Boston. Though barely two pages, it stands as a counterpoint to a much, much larger and more famous work, The Education of Henry Adams. From this speech we also learn, incidentally, that what Holmes considered to be the greatest moral experience of his life was not what many scholars have thought. It was not the Civil War, that he called the second greatest moral experience of his life. It was entering the legal profession.Footnote 34

This revelation changed how I saw Holmes and how I understood his relationship to the legal profession. In my effort to understand what he meant by the “stereoscope of history” I stumbled upon the happy fact that his father had invented the wildly popular and economical hand-held viewer. It contributed to a boom in stereographs, the cards upon which the paired images were placed; all of a sudden, Victorian America’s drawing rooms burst with photos of exotic peoples and locales. It was not lost upon me, though, that Holmes does not gush about the wonders of the stereoscope but almost off-handedly uses the device to suggest how historical study has the power to bring law to life.

But more than historical study is needed to make law three-dimensional. The stereoscope provided depth to images that were otherwise flat; that is, they already had height and width. That height and width corresponds to law existing in the unreflective present. The stereoscope becomes useful when joined with the analytical power to clarify issues, understand consequences, and make ever-finer discriminations from a specific standpoint. The legal mind that studies the law’s past for the sake of applying law to the present and providing guidance to the future must be both perceptive and analytical. The more sophisticated and informed its discriminations the better because the better it will be able to communicate, in narrative or propositional form, the values that law either sought to protect, seeks to protect or, more fundamentally, uses to structure and energize itself.

Dimensionality in the way I am using it requires temporal perspective. Temporal perspective, in turn, unbolts the trapdoor of the present, the here-and-now; it gives one a greater feel and sense for the different actualities embedded in our lives. It works mainly through positioning and contrast. It may also on occasion lead one to question, or push against, the felt necessities of the present. These terms are admittedly vague. I hope that in the course of this book their meanings will become clearer. I also hope it will become evident why Holmes believed American law had to turn in on itself; it had to become self-reflexive. He also believed that the most truthful, intelligent, and most carefully proportioned story of law’s growth would fortify a young and expanding democracy. Such a story might protect the country against the pressing social and cultural crosscurrents that threatened to wreck it.

Three-dimensionality forces into position and into relief what otherwise is free-floating, undefined, gray, amorphous, and concealed in seemingly definite, meaningful, and robust-sounding abstract words or general propositions. Three-dimensionality also makes it possible to coordinate what Holmes called “intellectual interest” and “the facts of the law.” It also has the potential to lead to a needed legal positioning or navigational system (what I have also called a metric), one that would, in turn, permit a finer and richer canvassing of disputed cultural values than currently possible. At the very least, it can become an effective heuristic for developing professional judgment.

I take Holmes’s pedagogical program as stated in “The Path of the Law” to be an outline for developing professional judgment. It begins with the basics and leads, progressively, to more difficult challenges. The law student must learn the rudiments of professional judgment, the working lawyer must develop and perfect it, the judge must enact it, the law professor must enhance it. That professional judgment, though, is not a series of disconnected “its” but a complex of thought and behavior seen from different angles. Once the body of working legal professionals in this country has assimilated this way of thinking about professional judgment then perhaps a philosopher of genius would come along and validate the whole endeavor. Holmes thought that philosopher might turn out to be him; he suffered, though, from more than his share of doubt.

Let me now explain how the book is structured and how it is meant to progress, both as a work of intellectual history and as a contribution to legal theory. A more detailed synopsis to each part follows that part’s title page. The overview here has less detail but provides a wider scope.

Though this book is a study of Holmes, I do not begin Part I, “Law and the Legal Profession,” with his work. I begin with a brief look at a book closer to my chronological present, A. W. Brian Simpson’s Invitation to Law. I use Simpson’s book, published in 1988, as a portal into the nineteenth century. The reason I begin with Simpson is because I believe Holmes would agree wholeheartedly with a maxim that Simpson brilliantly formulated or wisely repeated (I am not sure which): Law is for lawyers.

The idea that “law is for lawyers” leads me to an era in American history, not the only one to be sure, during which that very assertion was hotly disputed. From the beginning of his legal career in the 1860s Holmes justified the profession in professional terms. It took deep learning and much practice to fully understand law; it was not intuitive. That learning began for lawyers with a single, intertwined question: “What is (the) law?”

The effort to understand this intertwined question, which I liken to a DNA double helix, led me to analyze the strands separately – “What is the law?” and “What is law?” – and then as a single entity. On the one hand, the analysis required canvassing how practitioners, and those who wrote materials to guide them, thought law ought to connect to various factual situations. “What is the law?” always began as an empirical question, but Holmes, for one, did not believe it should end there. He saw much virtue in fully exploring the other part of the problem, “What is law?” That dual approach led him to develop a sophisticated conception of how the common law established jurisprudential boundaries, or what John Austin called the “province of jurisprudence.” That section of Part I is akin to storyboarding a script. Part I also features detailed examinations of both the legal relationship we call “duty” and the consequence we call “penalty,” without which the common law would not exist as we know it.

On the other hand, Holmes recognized, as do I, that jurisprudential boundaries changed over time, as did the manner in which judicial authorities punished or did not punish, or otherwise encouraged or discouraged, the behavior brought to their attention. Duties had seen and unseen histories. One must become aware of these histories; integrated correctly they created a more expansive horizon and furthered nascent positioning capacities within the law. Holmes used a distinctive mode of argumentation – emphasizing apperception and triangulation – to explore these and related topics in The Common Law. He believed this mode best fit the distinctive characteristics of the cultural power we call law. Bringing out that distinctiveness is the goal of Part II, entitled “The Inner Path of the Common Law.”

For the sake of exposition it is often easier, for both writer and reader, to separate a complex, intertwined question, such as “What is (the) law?” into its static and dynamic aspects. I attempt to do that in Parts I and II. The harder endeavor is then bringing them back together. In that effort I am much indebted to James Willard Hurst’s singular book, Justice Holmes on Legal History. I have adopted Hurst’s terminology of sequence and context and have thought long and hard on what he has written. Meditating on Hurst has led me to pinpoint where he and I diverge in either our understanding of Holmes or in how each has chosen to envision and extend Holmes’s project. Like Justice Holmes on Legal History, this book works both with and against Holmes’s thought: “against” in the sense of grappling or wrestling with what Holmes meant on this or that issue or what he thought best for the future of law in this country; “with” in the sense of learning to think in sync with those Holmesian formulations too powerful to contest successfully (e.g., “The life of the law has not been logic: it has been experience.”).

Hurst made my own struggle both easier and harder. Easier because I could, and did, learn a lot from him. I could also draw some useful conclusions why academic lawyers have not devoted much attention to his study on Holmes and history. Harder because I had to take care not to supplant Holmes with Hurst. The whole matter became more manageable when I realized that Hurst had not been as deeply affected as I was by the notion, which Holmes first articulated in The Common Law, of a “purely legal point of view.”Footnote 35 Perhaps that was because Hurst did not practice law for a living and I do. Regardless, the purely legal point of view as Holmes describes it in The Common Law I take to be the first iteration of the point of view of the bad man made infamous in “The Path of the Law.”

Part III draws on Justice Holmes on Legal History to establish the necessary perimeters for the purely legal point of view. Holmes used the position of the legal professional to center that viewpoint, but, apparently, was not satisfied merely to have discerned by that means the liminal point where past and present meet. He wanted to entrench that point of view, to make it self-determinative; to give it increased height, width, and depth. Philosophical or theoretical justifications provide invaluable assistance in such endeavors; they structure insights and bind aperçus. Though Holmes never completed the task to the extent he probably wished, he did leave us with “Law in Science and Science in Law.” That 1899 article contained the pithiest statement of his fundamental theorem of the law: “as to any possible conduct it is either lawful or unlawful.”Footnote 36

One main thesis of this study is that Holmes’s theorem of law restates in formal terms the insight he first had in The Common Law. The purely legal point of view makes increased intraprofessional awareness – another description for three-dimensionality – possible. That, in turn, provides the needed conditions for establishing a metric of the law. This metric, in my use, is a single mode of differentiation and integration. It provides the necessary means to increase law’s (that is, the work that legal professionals do) intelligence and intelligibility, or, in equivalent terms, perspicuity and transparency. It enables law to become more knowable. Part III ends by exploring this paradoxical claim that through our own dedicated purposiveness, formalized and implemented through the idea of a metric, we can increase the capacity of the law to be known.

The very long Part IV is the hardest to explain. In a sense, it forms its own distinct unit, as do Parts I–III, on the one side, and Part V on the other. Entitled, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Bad Man,” it reviews and analyzes selected interpretations of the bad man and “The Path of the Law” from the turn of the twentieth century to the present time. Yet its progression is not exactly chronological. My best defense – beyond any historical interest or value it may possess – is that it is an effort to show how one brings dimensionality, vividness, proportion, and depth into the scholarly study of law. I have tried to demonstrate how one begins to create a three-dimensional perspective by bringing to the fore, and setting into relief and juxtaposition, the manner in which many different legal scholars have conceived the identity of the bad man and Holmes’s point for introducing him in “The Path of the Law.”

In the limited exploration of this one issue, what stands out are not the many divergences of interpretation, or the more-or-less extreme one-sidedness, or the repeat instances of self-induced ignorance, but a widespread, practically institutionalized incapacity – the inability of one legal scholar to care about the thought of another. Indifference is endemic. I do not mean “care” in the sense of footnote acknowledgment or surface critique; I mean good faith study; hard thinking, probing, interaction, and reflection. Critical to the creation of a three-dimensional view of law, as well as to a viable jurisprudence, is the de-flattening of the concerns, opinions, beliefs, and rationales that have no immediate, innate hold on our own. In our new era of limits we cannot continue blithely to disregard our co-thinkers or predecessors; to do so is wasteful and unproductive. We must learn to think through them, and they through us, not to achieve the same effect as a bullet, but to measure our thoughts against each other. Part IV in this respect attempts to add the placements of people and the directionalities of thought needed for depth and movement to the relatively static study of law contained in Part I, and to those elements of increased length (sequence) and width (context) and their interaction found in Part II.

The final part, which is even longer than Part IV, attempts to bring together the various topics addressed, and a few others, for the ultimate goal, not of synthesis, but of positioning Holmes’s theory of legal study within his own vision of American law as I have come to understand it. That vision recognizes American law as an actual, ongoing, dynamic enterprise, one that attempts to control the different rates of movement that affect the different scales at which the law operates.

Bringing those scales into congruence may have been a long-cherished hope of Holmes. Politics and legality form in his eyes their own magnetic polarity. One had to measure movement, draw lines, and slowly, through patient, collective endeavor, turn law into a self-realized dimension of existence. In a way, this proposed endeavor provides a mode for natural evolutionary processes to become self-conscious. One had to understand the constitutive role of legal procedure. One had to become more sensible to the legal profession’s synchronic and diachronic dimensions. One had to become more clear-eyed about the surreptitiousness of the past. One had to understand the fundamental role of professional judgments, how they worked off each other to build and inform a working profession.

A three-dimensional view of law helps to advance all those goals. It also becomes a way to extend perception and build-out knowledge of those legal acts Holmes believed dispositive, those that led to the temporal harm law sought to prevent or redress. That building-out may not be doable in the way Holmes imagined, systematically, but one could do it through topographical representations. Regardless of how one sought to depict the knowledge had or perception gained, Holmes believed uniquely American law began with practicality and he thought legal education should begin there as well. But it should not stay there. To bring into unison the different dimensions of American law required a new and different type of perspective, one purely legal. That perspective recognized law as a distinctive form of knowledge, a unique discipline – especially in the American context – of power.