Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Indians in Malaysia: The Social and Ethnic Context

- 2 Tamil Traditions and South Indian Hinduism

- 3 Colonialism, Colonial Knowledge and Hindu Reform Movements

- 4 Hinduism in Malaysia: An Overview

- 5 Murugan: A Tamil Deity

- 6 The Phenomenology of Thaipusam at Batu Caves

- 7 Other Thaipusams

- 8 Thaipusam Considered: The Divine Crossing

- Conclusions

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Indians in Malaysia: The Social and Ethnic Context

- 2 Tamil Traditions and South Indian Hinduism

- 3 Colonialism, Colonial Knowledge and Hindu Reform Movements

- 4 Hinduism in Malaysia: An Overview

- 5 Murugan: A Tamil Deity

- 6 The Phenomenology of Thaipusam at Batu Caves

- 7 Other Thaipusams

- 8 Thaipusam Considered: The Divine Crossing

- Conclusions

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

Summary

In the Beginning

My first experience of Thaipusam occurred on 24 January 1978. Encouraged by Indian contacts who suggested that the festival might be of some general interest, I rose at 4 a.m., and accompanied by my wife, Wendy, four visitors from Australia, and a young Tamil man who had agreed to act as our guide, we made our way to Batu Caves, about thirteen kilometres north of Kuala Lumpur. Despite the early hour the area around the caves was already crowded and we had to park some distance from the main site. (Press reports calculated the 1978 attendance at 500,000 and I was later to find that many people had spent the night at the caves.) We threaded our way through the concourse to the very foot of the steps leading to the main cave (known as the Temple Cave), which would, we hoped, provide us with a privileged view of the festival and its participants.

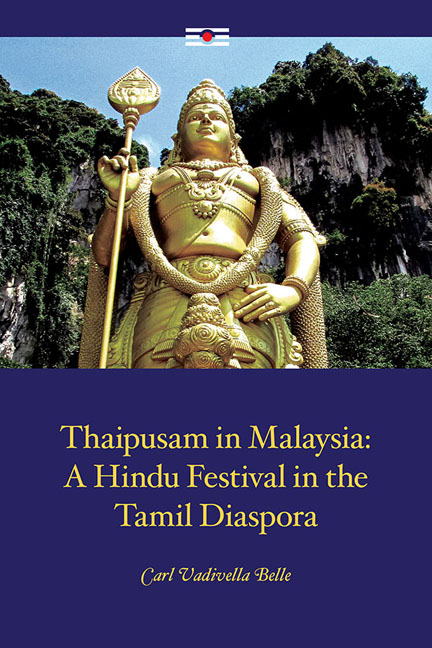

Since our arrival in Malaysia we had been fed a diet of highly dramatic (some might say sensationalist) stories of the Thaipusam festival. We had heard accounts of the numerous kavadi (ritual burden) bearers, their bodies pierced with skewers and hooks, carrying their loads up the sharp incline of the stairway leading to the main shrine within the Temple Cave; of the immense crowds; of the auditory overload, consisting of the chants and shouts of devotees, the constant drumming, the loudspeakers relaying amplified religious music as well as the droning speeches of visiting political dignitaries. And this festival was dedicated to the deity Murugan, a South Indian god so seemingly obscure and generally unknown that he earned but a brief paragraph in one of the putatively authoritative texts which had provided my background reading into Hinduism, and no entries at all in the remainder. Most of what we had heard about Thaipusam had comprised the impressions of the few expatriates who had visited the festival, and who tended to view it as a curiosity, a form of local colour, an incidental divertissement which provided a suitable touch of the “mysterious East” to round out their stay in “oriental” Malaysia.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Thaipusam in MalaysiaA Hindu Festival in the Tamil Diaspora, pp. xi - xxxiiPublisher: ISEAS–Yusof Ishak InstitutePrint publication year: 2017