Book contents

6 - The Rushdie Affair and Michael Dummett

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

Summary

I learned that very often the most intolerant and narrow-minded people are the ones who congratulate themselves on their tolerance and open-mindedness.

Christopher HitchensThe idea that we have to reach out to what was called “the Muslim community”, and that we could do this by empowering the most aggressive and fundamentalist figures and currents within that community, was widespread among Western progressivist and multiculturalist writers of the past decades. They propounded the idea that some sort of “balance” had to be found. This idea that somehow you have to deal with the fanatics, find some kind of compromise, was common and also found its way into monographs on the Rushdie Affair. Here I will discuss two of those books, viz. Paul Weller's A Mirror for our Times: “The Rushdie Affair” and the Future of Multiculturalism (2009) and Richard Webster's A History of Blasphemy: Liberalism, Censorship and “The Satanic Verses” (1990).

Weller's book is prefaced with an “acknowledgment of the loss of many years of personal liberty for Salman Rushdie”. He also speaks of a “loss of life and injury experienced by a number of people of various backgrounds throughout the world who became caught up in the violent events that occurred around the controversy”. But then he speaks of an equal part of the “passion and pain of many ordinary offended Muslims who felt their concerns had been misunderstood by the general non-Muslim public of the ‘Western world’, and who also felt betrayed by the liberal intelligentsia”. And there we have the notion of betrayal again.

What Weller fails to do, however, is assessing the reasonableness of the “feelings” (of betrayal) he describes. He takes those feelings at face value (as Taylor did, as cited earlier). As something you cannot judge. But how reasonable are my feelings when I tell you I feel “betrayed” if you have a different opinion of my sacred values than I do? Do I have the right to feel “betrayed” when you do not, as I do, consider Schopenhauer (1788-1860) the greatest philosopher of all times? You did not promise me in advance you would go along with my feelings, did you?

This whole idea of betrayal, an idea we also find with Taylor, and more extremely with Michael Dummett whose ideas I will discuss in a moment, is strange.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

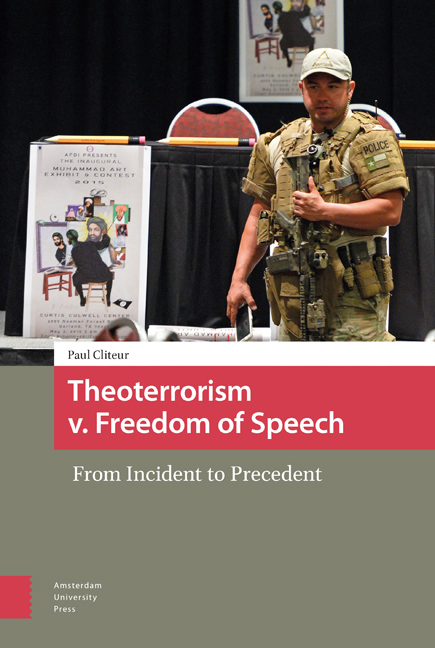

- Theoterrorism v. Freedom of SpeechFrom Incident to Precedent, pp. 159 - 198Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019