Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Troubling Images: An Introduction

- 1 The Trajectory and Dynamics of Afrikaner Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: An Overview

- One Assent and Dissent Through Fine Art and Architecture

- Two Sculptures on University Campuses

- Three Photography, Identity and Nationhood

- Four Deploying Mass Media and Popular Visual Culture

- Contributor Biographies

- Index

4 - Afrikaner Identity in Contemporary Visual Art: A Study in Hauntology

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 March 2020

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Troubling Images: An Introduction

- 1 The Trajectory and Dynamics of Afrikaner Nationalism in the Twentieth Century: An Overview

- One Assent and Dissent Through Fine Art and Architecture

- Two Sculptures on University Campuses

- Three Photography, Identity and Nationhood

- Four Deploying Mass Media and Popular Visual Culture

- Contributor Biographies

- Index

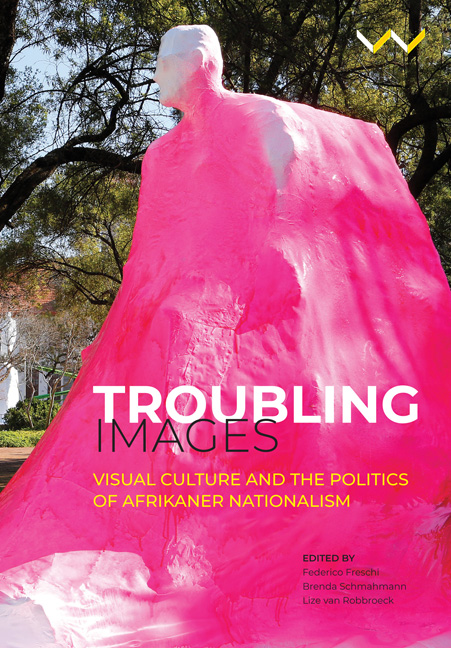

Summary

Considering the persistence of the many structural inequalities and racial taxonomies forged during colonisation and institutionalised under apartheid, South Africa altogether figures as a haunted nation. Jacques Derrida's concept of hauntology, which suggests that our personal and political ways of being resemble the phenomenon of being haunted (2006, 10), offers a compelling framework for reflecting on the relationship between spectral powers, post-apartheid Afrikaner identities, and contemporary visual art in particular. Derrida's Specters of Marx (2006) is frequently cited as the major catalyst for the continuing interest in haunting as a theoretical approach in cultural studies and other disciplines. Indeed, fragments of lost time are constantly reanimated by historiography and memory, and implicate us in various moral and social dilemmas in the present. Thus, at the core of Derrida's thesis resides an ethics: instead of begrudging our status as heirs to the past, we are compelled to welcome and negotiate with spectres in order to realise social justice.

The ghost or spectre is therefore liberally employed in contemporary critical theory as a conceptual metaphor befitting, for example, revisionist readings of history, perspectives on the itinerant status of the disenfranchised (such as political refugees), and the politics of trauma, remembrance and commemoration. Spectral readings of the South African landscape are, for example, adept at addressing the erasure (and lingering traces) of communities physically and psychologically displaced by apartheid (Buys and Farber 2011; Jonker and Till 2009; Shear 2006). I apply such spectral reading vis-à-vis existing research on Afrikaner ethnicity to selected works by a number of contemporary South African artists who participated in three consecutive exhibitions, Ik Ben Een Afrikander [I am an Afrikaner/African] I, II and III (2011–2012), which culminated in a travelling exhibition, Ik Ben Een Afrikander: The Unequal Conversation (2015–2016).

The exhibitions, curated by Teresa Lizamore and shown at various locations across South Africa, included numerous works of painting, photography, sculpture, site-specific installation and video, created by nearly 30 individual South African artists. The curatorial intent of the exhibitions is an attempt to locate and critically examine the position of contemporary Afrikaners (that is, white Afrikaans-speakers) in relation to their controversial past, which to some degree complicates (and almost invalidates) their legitimacy in the present (Lizamore 2012).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Troubling ImagesVisual Culture and the Politics of Afrikaner Nationalism, pp. 92 - 116Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2020