Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 A bronze drum

- 2 Boar Tusk's children

- 3 White collar Flowerland

- 4 True Love at home

- 5 Water child, land child

- 6 A simple man

- 7 Fighting mean, fighting clean

- 8 Great Lake and the Elephant Man

- 9 Bartholomew's boarders

- 10 The three seasons

- Interlude: from the Kok river

- 11 Last of the longhouses

- 12 A delicate bamboo tongue

- 13 True Love in love

- 14 Fermented monkey faeces

- 15 Perfect hosts

- 16 Old guard, young Turks

- 17 True Love and White Rock

- 18 Insurgents in a landscape

- 19 True Love and sudden death

- 20 Portraits

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

14 - Fermented monkey faeces

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 October 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1 A bronze drum

- 2 Boar Tusk's children

- 3 White collar Flowerland

- 4 True Love at home

- 5 Water child, land child

- 6 A simple man

- 7 Fighting mean, fighting clean

- 8 Great Lake and the Elephant Man

- 9 Bartholomew's boarders

- 10 The three seasons

- Interlude: from the Kok river

- 11 Last of the longhouses

- 12 A delicate bamboo tongue

- 13 True Love in love

- 14 Fermented monkey faeces

- 15 Perfect hosts

- 16 Old guard, young Turks

- 17 True Love and White Rock

- 18 Insurgents in a landscape

- 19 True Love and sudden death

- 20 Portraits

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

‘To the Buddhist Bishop of Toungoo we are indebted for a suggestion that “Karen” is derived from a Pali word meaning “dirty eaters”.’

Lt Col MacMahon (1876, p. 45).But the Bishop was surely wrong. However once well deserved the Karen reputation for filth, in one tiny respect they have always been fastidious – as Capitaine Lunet de Lajonquière discovered in 1904:

Personally I never saw them wash anything other than the very tips of the fingers of the right hand, with which they took the sticky rice from the communal pot to knead it into balls–though this hygiene was never extended to include the whole hand.

There is no doubt about their enthusiasm for rice. Sam, Bartholomew's son, would pack the soft white mass into his mouth with a frenzy that even the girls of Boarders found repulsive; they wouldn't sit next to him at meals. Sam could perhaps plead force majeure; even before the outbreak of war, the Karen would say to their children, ‘Eat fast, the Burmese are coming!’ Medical Officer Timothy had a capacity for rice that I hope never to see equalled. On our tours together he would sit himself down to supper in someone's thatched kitchen and devour five large platefuls in the time that I took over one and a half. Afterwards he would rise from the meats with a beatific smile – and then suddenly clutch his belly and start groaning, after which he'd have to lie down in pain for an hour. He claimed to have a hernia, and one could see why. Many Karen suffer agonies of indigestion; ‘wind pain’, True Love called it, swearing that it sometimes rendered them unconscious.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

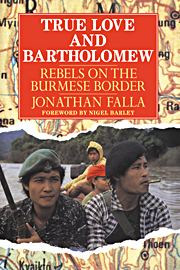

- True Love and BartholomewRebels on the Burmese Border, pp. 263 - 281Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 1991