Gossip is a strange kind of indulgence, the satisfying effect of which consists in the realization that other people do wrong. It gives us pleasure to point out the existence of evil in others. To give vent to that pleasure is gossip. In gossip we are pleased to discuss other people’s faults, seldom their merits. We thus seem to enjoy evil for evil’s sake. For we are pleased by faults and errors. We are content to see them endure and grow. We are eager to augment their number and to exaggerate their importance. And, mark you, we derive no profit or personal advantage from doing so. If we do, we no longer call it gossip but either libel or slander; gossip is idle and aimless […] gossip is not merely a ludicrous weakness … but a social force, an intricate mechanism through which the organized forces of evil gain access to various departments of human life. In the language of theology, … gossip may properly be called one of Satan’s chief weapons in his design to rule over the world. The Devil has been repeatedly conceived as archgossiper. “How did the Devil fall?” asks Jerome. “Was it after a theft, a murder, an adultery? In truth, these things are sins, but it was not through any of them that the Devil fell. He fell because of his tongue.

1 The Puzzle of Sustainable Cooperation

Gossiping and the reputation effects it produces are widely viewed as the most powerful mechanism to sustain cooperation without the intervention of formal authorities. According to the underlying standard rational choice account, gossiping is an almost costless activity and therefore the ideal instrument to facilitate monitoring and sanctioning of those violating norms (Reference ColemanColeman, 1990). This sanction threat, in turn, increases the likelihood that rational, forward-looking individuals stick to the rules in order to avoid the negative consequences that a bad reputation will bring. The result is a self-reinforcing gossip-reputation-cooperation triangle.

The present Element examines this influential claim in more detail. We argue that this seemingly straightforward narrative and its underlying reasoning is incomplete at best, and in some cases actually leads to wrong predictions. Building on evolutionary research’s recent insights into social rationality and the importance of so-called goal frames (Reference Lindenberg and StegLindenberg & Steg, 2007), we develop an alternative explanatory framework. This framework acknowledges that evolution equipped humans with a highly flexible and strongly situation-dependent set of three overarching mindsets (or overarching goal frames) that compete for being in our cognitive foreground. These mindsets structure our thinking and strongly influence our motives. The gain goal frame – the core assumption of standard rational choice models in economics – is but one of these mindsets. It makes us sensitive to opportunities for improving our resources. The normative goal frame – which informs the Homo socialis model of most other social science approaches – is another one. It instigates us “do the right thing.” Finally, the so-called hedonic goal frame triggers us to do what feels good right now. The hedonic goal frame to this point has largely remained under the radar of the science of cooperation in general, and of gossip and reputation scholars in particular. As we will show, this is a major oversight. It is the hedonic mindset that tends to trump gain and normative concerns, unless these receive extra backing from our social environment. This means that most gossip will be driven by hedonic motives, and therefore, we argue, be unlikely to have strong reputation effects. In sum, our goal framing approach yields a variety of new predictions, some of which are at odds with the standard account, but better aligned with the available empirical evidence. It bridges many of the current knowledge gaps and resolves contradictions in the field because it is one of the very few theories of action that is able to reconcile the competing claims about human nature. As a cognitive-behavioral approach anchored in evolutionary research, goal framing theory provides a more refined and more accurate psychological microfoundation for the gossip-reputation-cooperation triangle.

Section 1 first outlines the assumptions and propositions behind the “standard” model. This is followed by a description of the fragmented, incomplete, and inconsistent state of the art in the research field. Section 2 gives a summary of current evolutionary approaches to gossip, reputation, and cooperation. It uses Tinbergen’s “four questions” to structure the summary. Section 3 introduces the goal framing approach and its core assumptions. Section 4, on gossip and reputation in contemporary society, applies goal framing theory to review current explanations and evidence linking culture, structure, situations, dispositions, and technology to how gossip and reputation may influence cooperation. Section 5 concludes with an exploration of open questions and the contours of a research agenda.

1.1 Gossip and Reputation: Golden Key to Cooperation?

Controversy about gossip, its alleged motives and consequences, and how to deal with them, seem to be a feature of many societies. For some scholars, such as Henry Lanz, the author of the opening quote writing about religion in Western societies, gossip is “Satan’s chief weapon,” an indulgence that satisfies our lowest desires – such that we derive our satisfaction not from some personal benefit that may come with gossiping, but from the mere pleasure we experience from harming others (Reference LanzLanz, 1936). Indeed, most cultures have very strong norms against gossiping, especially against women gossiping (Reference Emler, Goodman and Ben-Ze’evEmler, 1994). Islam considers backbiting as the 41st Greater Sin, and also the Bible explicitly condemns gossipers. For example, Psalm 101:5 reads: “Whoever slanders his neighbor secretly I will destroy.”

In contrast, there are societies that engage in a far more pragmatic approach when it comes to gossip. In Rome in the first century AD there were enslaved men, such as Aristarchus, who served as nomenclator – a “caller of names,” or better, a “social secretary.” We know about Aristarchus because his patron took the effort to dedicate an epigraph to his nomenclator as an indication of how important Aristarchus’ services must have been for him (Reference WilsonWilson, 1910). Nomenclatores played an important role for members of the Roman elite, who often also aspired to make it into powerful political positions. In order to succeed, they needed to solicit support and potential votes from their clients and other influential members. Whenever patrons participated in public gatherings or strolled in public places, their nomenclatores would walk closely behind them. Every time their patron approached someone of importance, the nomenclator would not only remind his patron about the person’s name, but also provide relevant evaluative information about their business and current situation, their kinship and social relations, what the patron had done for the client in the past and vice versa. With patrons’ networks of clients and supporters going into the hundreds, avoiding the embarrassment of not recalling a client’s name was an essential part of keeping one’s support relationships going. The role of a nomenclator reflects one of the most institutionalized forms of how a society may regulate and normalize some of the reputation management that is achieved through gossiping.

Gossip as evil, as a sin, or as a powerful political tool nicely capture the multi-faceted phenomenon that gossip is, and these quite diverse descriptions also to some degree symbolize the wide gaps that characterize current scholarly endeavors to come to grips with it. These gaps range from assumptions about the motives behind engaging in gossip to its alleged benefits for the individual or the group. But both gossip as sin and gossip as a political tool also share a common message, and this is that we should be aware of the tremendous societal impact that gossip may have. While this insight may be an open door for many, social scientists’ awareness of gossip’s potentially crucial role is of relatively recent date. For a long time, gossip had not been considered as a topic for serious scientific study, remaining confined to the realm of specialized anthropological case studies (Reference Emler, Goodman and Ben-Ze’evEmler, 1994; Reference GluckmanGluckman, 1968). This changed with the 1996 publication of Robin Dunbar’s influential book Grooming, Gossip and the Evolution of Language. Dunbar’s thesis was that gossip evolved as a means that helped human groups to build and cement social bonds without having to directly interact with every other member of their group. This “social grooming” not only played an essential role in the evolution of language – which allows us to share information about third parties – but also to create social order and to sustain cooperation in groups. Dunbar’s account provided innovative answers to important questions related to the evolution of gossip (see Section 2 for a detailed discussion). What is gossip’s function or adaptive value for humans? How did it evolve in the human species? What are the neurocognitive processes and mechanisms behind it? With Dunbar’s contribution, a practice that up until then many had considered as being merely a trivial epiphenomenon of social group processes suddenly had become one of the key levers enabling the evolution of cooperation in human societies.

1.1.1 Cooperation Sustainability Is Key for Society

Cooperation, or the joint realization of mutual benefits, is fundamental for all social species to thrive, and human societies are no exception. It can take many forms. Whether it is about contributing one’s fair share to a team effort, about helping your neighbors renovate their kitchen, about paying your taxes, or about volunteering for a nongovernmental organization: it is through cooperation that we can realize outcomes that individual effort alone would never be able to achieve.

Cooperation’s importance for society has long been acknowledged, and much scholarship has been devoted to study how to get cooperation going. More recently, the question how to sustain cooperation in the longer run has entered center stage.

1.1.2 Current Research Suggests That Gossip and Reputation Solve the Problem of Cooperation Sustainability

Current scholarship considers the opportunity to develop and act upon reputations as the single most important mechanism enabling and sustaining cooperation, including among selfish individuals. The focus on reputation as a major mechanism to enhance cooperation has both theoretical and empirical reasons.

For one, the disciplining effects of reputation can emerge endogenously as the result of the interactions among autonomous individuals. The related processes are self-reinforcing; individuals can freely contribute information to build or break reputations, and no formal centralized sanctioning institutions are required for it to work.

Another reason for the success of reputation is the extensive adoption of online rankings and reputation systems (see Section 5 for a discussion of their relationship with gossip). However, in the offline world, gossip is the way in which reputations are built and destroyed because of its alleged efficiency and effectiveness: gossiping may be almost costless for the gossiper, but it can have a strong impact in reinforcing social norms (Reference ColemanColeman, 1990, pp. 284–285). Without going into definitional issues, it is worth mentioning that there is a remarkable number of different definitions of gossip, as highlighted by a recent systematic meta-review reporting 324 articles from which it is possible to extract a definition of gossip (Reference Dores Cruz, Thielmann and ColumbusDores Cruz et al., 2021). From this plethora, we select two that are especially relevant for our argument. Gossip is “gossip is the exchange of personal information (positive or negative) in an evaluative way (positive or negative) about absent third parties” -and put “evaluative way” (Foster, 2004, emphasis ours), and a more elaborate account would define gossip as: “sharing evaluative information about an absent third-party that the sender would not have shared if the third-party were present, and which, according to the sender, is valuable because it adds to the current knowledge of the receiver” (Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a, p. 2). Both definitions show that gossip is more than knowledge sharing, because what is reported is valuable and it could have been difficult to find out, were the gossip not shared.

However, research on gossip and reputation has mostly focused on gossip as information transmission, developing what we define as “the standard model of reputation-based cooperation.” Although very useful in some settings, the standard model does not explain under which conditions gossip does or does not happen, and why it does not work in sustaining value creation. The standard model and its argumentation are simple. In social settings where the transmission or exchange of information about third parties is possible, sharing information about the characteristics of one’s interaction partners – such as their reliability or trustworthiness – results in the formation of individual reputations, or shared beliefs about an individual’s characteristics (Reference Nowak and SigmundNowak & Sigmund, 1998, Reference Nowak and Sigmund2005). Such beliefs contribute to a self-reinforcing system of sustained cooperation. The opportunity to select cooperative partners in a “market for cooperators” (Reference Noë and HammersteinNoë & Hammerstein, 1995) and avoid defectors deters potential norm violators because their noncompliance may ruin their reputation, which in turn may deprive them of beneficial exchanges in the future. Reputations therefore work both as an ex ante and an ex post device. The simple possibility or threat that someone might spread negative gossip about our misdeeds would keep us from engaging in them (Reference Piazza and BeringPiazza & Bering, 2008), and if we do, we will be disciplined by others turning their back on us. The resulting triangle linking reputation and gossip to cooperation sustainability currently constitutes one of the most fruitful theoretical developments in the field of cooperation science (Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a; Reference Giardini, Balliet, Power, Számadó and TakácsGiardini et al., 2022).

It is important to also highlight four additional assumptions behind this standard model that often remain implicit. First, gossip affects reputations because it transmits accurate (i.e., honest and reliable) information. Gossip veracity is essential for the gossip-reputation-cooperation mechanism to function (Reference Fonseca and PetersFonseca & Peters, 2018; Reference Nieper, Beersma, Dijkstra and van KleefNieper et al., 2022; but see Reference Laidre, Lamb, Shultz and OlsenLaidre et al., 2013, who argue based on findings from an agent-based model that verifying information with multiple sources can alleviate problems of “noise” in gossip networks). Second, there is a common evaluative reference point that makes it easy to judge when behavior is noncooperative or cooperative. That is, there is a social norm that prescribes or proscribes which behaviors are appropriate or not (Reference Lindenberg, Wittek, Giardini, Buskens, Corten and SnijdersLindenberg et al., 2020). Third, the available evaluations of third parties enforce cooperation because people act upon these reputations, for example by further spreading the information, but most importantly by sanctioning the norm violator (Reference ColemanColeman, 1990). Gossip thereby has the potential to resolve what is known as the second-order free-rider dilemma, according to which sanctioning is costly, and individuals therefore prefer others to do the sanctioning if they benefit from it, as is the case in collective-good situations. Fourth, sharing evaluative information does not have negative consequences for the gossiper (Reference GiardiniGiardini, 2012; Reference Hauser, Nowak and RandHauser et al., 2014). Where such antisocial punishment is possible and frequent, for example because the norm violator takes revenge, cooperation declines.

Researchers have accumulated considerable evidence, most of it based on controlled lab experiments, demonstrating that social settings that allow for gathering and sharing information about individual reputations fare much better in sustaining high levels of contributions to collective goods compared to settings in which this information cannot be shared (Reference Milinski, Giardini and WittekMilinski, 2019). This standard model of reputation-based cooperation, though, fails in answering two key questions. First, why do people gossip? Even if spreading information about an absent third party can have no immediate costs, still the gossiper can be punished by the target or by the whole group if the intention behind gossip is perceived to be malevolent. Second, the standard model assumes that people have either a selfish motive to spread gossip (to punish the target, to ruin their reputation or their social standing), or an altruistic one, that is, providing norm-abiding behavior and punishing defectors. We will argue in this Element that the whole picture is more complex than this, and that understanding gossip as a goal-driven behavior can shed light on the conditions under which gossip and reputation can sustain cooperation. Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual model behind our argument.

Figure 1 Conceptual model

1.2 The Gossip Landscape: Fragmented, Incomplete, and Inconsistent

The gossip-reputation-cooperation triangle underlying the current “standard model” of cooperation assumes a three-step sequence, with each step representing a causal mechanism (see Figure 1):

(1) Cooperative or noncooperative behavior by one party (A) toward another (B) triggers the latter to share positive or negative gossip about A’s behavior with third parties (C).

(2) Gossip, in turn, affects the first party’s (A) reputation as a cooperator or noncooperator, and it is the threat of being gossiped about that keeps (A) from defecting. That is, it is the threat of being gossiped about that keeps people in line.

(3) Third parties (C), in turn, base their decision whether or not to cooperate with (A) based on this reputational information.

Hence, each of the three mechanisms needs to work if cooperation is to be sustained. The link between reputation and cooperation (step 3) constitutes the core of the triangle. If reputational information is available and correct, and the rules of the game allow selecting and abandoning exchange partners, cooperation can in principle be sustained. But as this section will show, the interrelations between them are less straightforward than they appear at first glance. First, reputations may be biased, incomplete, or wrong (Reference Fehr and SutterFehr & Sutter, 2019; Reference Fonseca and PetersFonseca & Peters, 2018; Reference Sommerfeld, Krambeck and MilinskiSommerfeld et al., 2008), which may severely undermine the alleged corrective effect of reputation on selecting the “right” exchange partners, as postulated in arrow 3 of Figure 1.

Second, experienced (non-)cooperation may not always lead to gossiping, as implied in arrow 1 of Figure 1. In fact, there are many good reasons why individuals may even deliberately refrain from sharing this information with others (Reference Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019b). Conversely, gossip may be triggered by many other motives than the desire to share information about somebody’s (non-)cooperative behavior. Third, gossiping may not always have reputational effects, as stipulated in arrow 2 of Figure 1. For example, as one study has demonstrated, much gossiping anticipates the potential approval by the receivers, thus mainly echoing the receiver’s evaluation of the third party (Reference Burt, Rauch and CasellaBurt, 2001).

1.2.1 The Available Scientific Record on Gossip, Reputation, and Cooperation Reveals Major Empirical Inconsistencies

Empirically, a key puzzle in cooperation research is the consistently replicated finding that contributions to public-good experiments start at high to moderate levels, but then show a steady decline over time due to the proportion of “free riders” increasing. Or, as one scholar recently has succinctly summarized it: “The ability to cooperate is a central condition for human prosperity, yet a trend of declining cooperation is one of the most robust observations in behavioral economics” (Reference FosgaardFosgaard, 2018, p. 1). This pattern has been documented by two influential reviews, published almost two decades apart (Reference ChaudhuriChaudhuri, 2011; Reference Ledyard, Kagel and RothLedyard, 1995). More recent studies show similar outcomes (Reference Andreozzi, Ploner and SaralAndreozzi et al., 2020; Reference Burton-Chellew, Nax and WestBurton-Chellew et al., 2015; Reference Duca and NaxDuca & Nax, 2018; Reference FosgaardFosgaard, 2018). These patterns constitute a major challenge for the dominant narrative that considers reputation processes as the golden key to sustainable cooperation. Even more important, there are no empirical or field studies to date about how reputation sustains cooperation over time, and the available knowledge on the topic comes mostly from computational models.

Early attempts to explain this consistent decline of cooperation point, among others, to decision errors or argue that the players need some time until they have learned to play the dominant strategy (which is not to cooperate). More recent accounts seek the explanation for cooperation decay in the heterogeneity of player types or stable dispositions, distinguishing between conditional cooperators and free riders. Whereas conditional cooperators are optimistic concerning the contributions of others and therefore contribute, they discover through time that others free-ride, which in turns leads them to reduce their contributions. Hence the decay in cooperation. The conclusion from many experimental studies is that people who are conditional cooperators act like this independently of the situation they find themselves in. But, as other researchers have pointed out, the assumption of stable preferences, also for conditional cooperation, is quite a strong one. It cannot be ruled out that conditional cooperation, rather than being the result of a person’s “type,” may be the plain consequence of this person being responsive to group pressure, as Reference ChaudhuriChaudhuri (2011) remarks in a footnote, referring to empirical findings from Reference Bardsley and SausgruberBardsley and Sausgruber (2005) and Reference CarpenterCarpenter (2004). Conditional cooperation therefore may reflect adjustment to the social context – in this case conforming to the expectations of others (Reference Dana, Weber and KuangDana et al., 2007; Reference Heintz, Celse, Giardini and MaxHeintz et al., 2015), rather than being the consequence of a stable preference for conditional cooperation.

Another puzzling insight related to the alleged stability of individual dispositions is that gossip may be motivated by what has been called the “dark triad,” that is, “a constellation of personality traits, characterized by callousness and the tendency to manipulate others to one’s own benefit”: psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism (Reference Kniffin and WilsonKniffin & Wilson, 2005). If gossip is mainly spread by individuals with this kind of psychopathological trait, then questions arise about the viability of reputation as a reliable mechanism governing cooperation.

The internal structure of groups – such as the web of social and functional relationships linking its members – can be another potential factor leading to reputation mechanisms failing to sustain cooperation, because gossip does not work as predicted. Reference Kniffin and WilsonKniffin and Wilson (2005) stress that the incidence of gossiping is likely to be higher in settings with stronger interdependence and shared goals, as is frequently the case in work contexts. But there are also reasons to be cautious about this kind of claim. Regardless of the fact that most cultures have strong norms prohibiting gossip, and that most gossip research implicitly assumes that these norms are violated on a large scale, there are many situations in which it may not be in the best interest of a potential gossiper to share sensitive third-party information with others. This is illustrated by an interview study with 251 physicists and biologists in three different countries. Exploring the role of gossip as a means of social control related to scientific misconduct, the authors concluded that whereas gossip can be punitive, it is usually not corrective and therefore often not effective (Reference Vaidyanathan, Khalsa and EcklundVaidyanathan et al., 2016). As the accounts from victims of scientific misconduct vividly describe, all of them think twice before bad mouthing another scientist, be it a colleague, a superior, and in particular high-status seniors. Too strong is the fear of potential repercussions for one’s own career or reputation. The study also adds to earlier observations concerning the detrimental effects gossip may have on trust and morale (Reference Akande and OdewaleAkande & Odewale, 1994; Reference Baker and JonesBaker & Jones, 1996; Reference Van Iterson and CleggVan Iterson & Clegg, 2008), and to field research that has put the purported ubiquity of gossip into perspective. For example, a study by Reference Dunbar, Marriott and DuncanDunbar, Duncan, and Marriott (1997), based on systematic eavesdropping in trains, reports that “only about 3–4% of conversation time centers around ‘malicious’ (or negative) gossip in the colloquial sense” (p. 242). Unfortunately, there is hardly any systematic empirical research about the conditions under which potential gossip is quite likely not to be shared (Reference Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019b).

Furthermore, also the characteristics of the “moment” or the situation may significantly impact the proper functioning of gossip-based reputation mechanisms. For example, whereas a straightforward approach to explain reactions to norm violations would suggest a linear correlation between the severity of the infraction (e.g., in terms of the negative effects for others) and the strength of the reaction, this is not always the case. According to this view, people would leave it at gossiping when faced with minor infractions, and resort to more direct confrontations for major ones (Reference EllicksonEllickson, 1991). But the limited evidence that is available is not entirely consistent with this proportionality proposition. It suggests that gossip as a reaction to norm violations occupies a separate cognitive category, rather than being part of a single ladder of escalation. Instead, its use strongly depends on the characteristics of the situation, such as whether the offense represents a mishap or is part of a pattern that signals lack of normative commitment by the norm violator (Reference Wittek, Nooteboom and SixWittek, 2013). But this is further complicated by the fact that there seem to be cultural differences with regard to how appropriate gossiping is considered to be as a reaction to norm violations. For example, Reference Eriksson, Strimling and GelfandEriksson et al. (2021) found that gossip is more likely to be seen as an appropriate reaction to norm violations in individualist rather than collectivist societies with higher power distance, whereas other studies claim exactly the opposite (Reference GreifGreif, 1994). In sum, the cognitive mechanisms related to situational and cultural variations introduce yet another set of sources of potential gossip failure.

1.2.2 The Theoretical Foundation of Gossip Research Is Incomplete and Fragmented

Research on the triangle of reputation, gossip, and cooperation also faces at least two theoretical challenges. The first challenge refers to its incompleteness and fragmentation. It has three aspects. First, one issue relates to the large variety of conditions that were identified as causally relevant at multiple levels of analysis. As outlined in the previous section, researchers have linked gossip, reputation, and cooperation to intercultural and institutional variations at the level of nations, geographical regions, small groups, and organizations; to differences in an individual’s social position and personal social networks; to (new) means of communication, such as social media; to differences in personality traits and other individual-level dispositions; and to variations in specific social situations. Whereas empirical evidence leaves no doubt about the fact that each of these context conditions affects reputation, gossip, and cooperation, so far little effort has been made to analyze their interplay and relative impact.

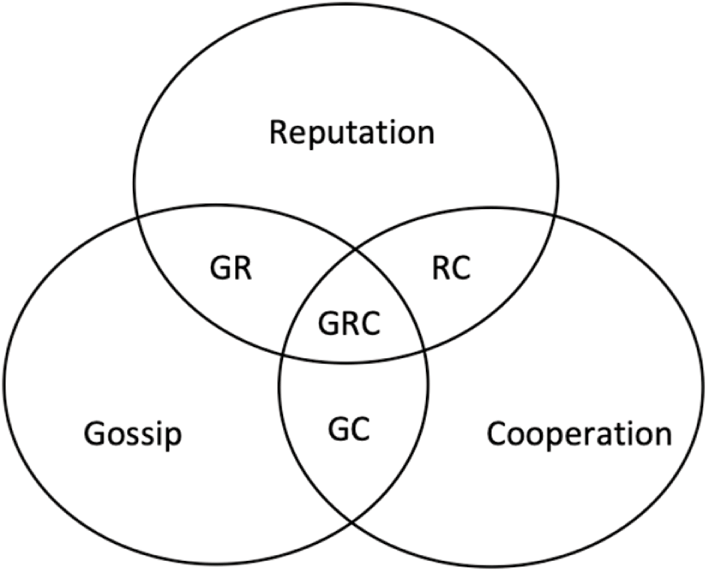

Second, much theorizing covers only part of the triangle, and sometimes does not disentangle different elements. There are three different literatures involving cooperation in combination with either reputation, gossip, or both (see Figure 2). Only a relatively small fraction simultaneously addresses the overlap of all three (GRC in Figure 2). The bulk of the literature consists of research on the antecedents of gossip and its eventual consequences, but this is not necessarily related to cooperation. This is followed by models focusing either on reputation or on gossip as antecedents of cooperation. This incompleteness is further aggravated by the fact that studies on gossip, reputation, and cooperation usually address only parts of the “gossip triad” (Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a), leaving many assumptions implicit. As our recent review has shown (Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a), even the four major explanatory mechanisms (reciprocity, punishment, coalition, and control) each rely on different assumptions and focus on different actors. For example, indirect reciprocity explanations focus on reputation effects for gossip targets and senders to explain changes in cooperation sustainability involving the target and the sender, whereas coalition models stress the importance of reputation effects for all three actors in the triad and link them to changes in cooperation sustainability among them. But a convincing model needs to be able to provide a consistent explanation not only for what might instigate a potential gossip sender to share third-party information. The same principles that are used to model cognitions, motivations, and behavior of potential gossip senders should also be able to capture the cognitions, motives, and behavior of the other actors in the gossip triad. So far, current theorizing seems to be far from such an integrated perspective, instead recurring on a large variety of disconnected “psychological effects” (Reference Manrique, Zeidler and RobertsManrique et al., 2021). For example, Reference Martinescu, Janssen, Nijstad, Giardini and WittekMartinescu et al. (2019) stress the importance of emotions as an antecedent and consequence of gossip for senders, receivers, and targets, whereas other researchers stress the social comparison motive for sender and receiver (Reference SulsSuls, 1977; Reference Wert and SaloveyWert & Salovey, 2004), and still others point to aggression or prosociality as important motives to share gossip (Reference Feinberg, Willer, Stellar and KeltnerFeinberg et al., 2012; Reference Jeuken, Beersma, ten Velden and DijkstraJeuken et al., 2015; Reference Testori, Hemelrijk and BeersmaTestori et al., 2022).

Figure 2 Venn diagram of research domains

Competing assumptions about human nature pose a different theoretical problem. These range from game theoretical models explicitly building on assumptions of full strategic rationality and selfish gain seeking on the one hand, to explanations invoking a wide variety of “nonrational” motivations and cognitions related to humans’ extraordinary capacity to cooperate (Reference Bowles and GintisBowles & Gintis, 2011; Reference Nowak and HighfieldNowak & Highfield, 2011) and the alleged innate prosociality of our species (Reference Burton-Chellew and WestBurton-Chellew & West, 2013; Reference Burton-Chellew, Nax and WestBurton-Chellew et al., 2015). The latter acknowledges that there may be systematic “deviations” from this model, which are also referred to as “cognitive biases” or “anomalies” (Reference Camerer and ThalerCamerer & Thaler, 1995; Reference Kahneman, Knetsch and ThalerKahneman et al., 1991). Accordingly, individuals’ motives to gossip have been attributed both to selfish and to group-serving intentions (Reference Bertolotti and MagnaniBertolotti & Magnani, 2014). But the question is not whether humans are either inherently prosocial or selfish, or which proportion of a group is of the “conditional cooperator” type, but rather under which conditions and why individuals keep acting cooperatively. The fact that different studies use different and often incompatible behavioral microfoundations makes theoretical integration difficult, if not impossible. Research meanwhile acknowledges the need for an integrated alternative microfoundation that is able to accommodate the seeming inconsistencies of earlier research (Reference Haselton, Nettle, Murray and BussHaselton et al., 2015). We argue that goal framing theory, an evolutionary theory of behavioral microfoundations, offers the necessary tools for building an integrated theory of the relationship between gossip, reputation, and cooperation.

2 The Evolutionary Origins of Gossip, Reputation, and Cooperation

The evolution of human cooperation has been framed as a puzzle to solve (Reference Boyd, Richerson, Levinson and JaissonBoyd & Richerson, 2006), as a challenge (Reference Apicella and SilkApicella & Silk, 2019), and as a paradox (Reference Németh and TakácsNemeth & Takacs, 2010). In the last twenty years, a significant number of review papers in many different disciplines, from biology to statistical physics and from developmental psychology to anthropology (a query on Google Scholar for review papers on “evolution human cooperation” published between 2002 and 2022 reported 88,100 results), have tried to take stock of existing research and to provide a convincing answer to the question: “How did cooperative behavior evolve in self-interested humans?” Indirect reciprocity (Reference AlexanderAlexander, 1987; Reference Santos, Pacheco and SantosSantos et al., 2021) and partner choice (Reference RobertsRoberts, 1998; Reference Roberts, Raihani and BsharyRoberts et al., 2021) are regarded as the most convincing explanations of the evolution of cooperation among nonkin. The possibility of gaining a reputation for being cooperative is a common feature of these two theories, which imply that reputations result from the past behaviors of actors and that the evaluation of these actions has consequences that can promote and sustain cooperation. Indirect reciprocity has perhaps been the most influential model of reputation-based cooperation (Reference AlexanderAlexander, 1987; Reference Nowak and SigmundNowak & Sigmund, 1998; Reference Panchanathan and BoydPanchanathan & Boyd, 2004). In this framework, individuals decide to cooperate (or not) with another, and this is reflected in the “image score” of the individuals, which will affect whether third parties cooperate with them (or not) in a future encounter (Reference Leimar and HammersteinLeimar & Hammerstein, 2001; Reference Nowak and SigmundNowak & Sigmund, 1998). Even if costly in the short run, reputational benefits gained through cooperation largely repay the initial investment. The benefits of a positive reputation are even larger according to the theory of competitive altruism, in which cooperation is a strategy to stand out and be selected for profitable partnerships (Reference BarclayBarclay, 2016; Reference Barclay and BarkerBarclay & Barker, 2020; Reference Roberts, Raihani and BsharyRoberts et al., 2021). In such a “biological market” (Reference Noë and HammersteinNoë & Hammerstein, 1995) positive reputations can be even more valuable than in a setting based on indirect reciprocity where partners are randomly drawn from the population (Reference Nowak and SigmundNowak & Sigmund, 1998). Before the formulation of the theory of indirect reciprocity (Reference AlexanderAlexander, 1987; Reference Nowak and SigmundNowak & Sigmund, 1998, Reference Nowak and Sigmund2005) reputation and gossip were on the research agenda of anthropologists (Reference GluckmanGluckman, 1968; Reference PainePaine, 1968) and social scientists (Reference Ben-Ze’ev and GoodmanBen Ze’ev & Goodman, 1994; Reference Emler, Goodman and Ben-Ze’evEmler, 1994; Reference GoffmanGoffman, 1949). The work of anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists complements biological theories by providing an overview of the functions served by gossip that are presumably rooted in our ancestral past (Reference Boehm, Giardini and WittekBoehm, 2019; Reference DunbarDunbar, 1996; Reference McAndrew, Giardini and WittekMcAndrew, 2019).

The explanations offered by the theories of indirect reciprocity and competitive altruism are both extremely influential and compelling, but they also rest on a set of simplifying assumptions. Evidence collected in highly controlled laboratory settings and theoretical insights from analytical and computational models provide support for indirect reciprocity theory and partner choice. However, there is an increasing awareness that in human groups gossip can be used to circulate false or inaccurate information, thus resulting in reputations that, being inaccurate, can hardly support cooperative behaviors and their evolutions (Reference Giardini, Vilone, Sánchez and AntonioniGiardini et al., 2022).

The link between evolution, gossip, and cooperation has been thoroughly explored in recent years, based on the assumption that knowing other people’s deeds before interacting with them can be a powerful tool to establish and support cooperation. In a complementary way, the consequences of being regarded as a defector in any kind of social interactions has such an array of negative consequences, that the “threat of gossip” is sufficient to enforce cooperation in multiple settings (for a review, see Reference Giardini, Vilone, Sánchez and AntonioniGiardini et al., 2021). Reputation is a belief or a meta-belief about what others think about someone (Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a), and it can be the end result of different kinds of behaviors (observation of someone’s actions, gossip, direct information from the target of reputation) performed by a multiplicity of actors. In what follows we will focus only on gossip intended as the action of spreading valuable information about an absent third party (Reference Emler, Goodman and Ben-Ze’evEmler, 1994; Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a). Gossip involves three specific relational acts: an act of attribution of some qualities, positive or negative, to someone else; an act of sharing, that is, communicating this attribution; and, finally, an act of perception by the receiver. Although the term “gossip” usually refers to what the sender does, the behavior is triadic in nature because there are three actors involved: the gossiper (or sender), the receiver, and the target (or object). When deciding whether, how, and to whom to gossip, these triadic relations enter the decision of the gossiper. The strength of the connections, together with the embeddedness of the gossip triad in a larger social network, all influence the occurrence and content of gossip, with possible effects on the reputation of the three actors, and on their cooperation (Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a). The question is: what is the evolutionary basis of such a complex decision in humans?

2.1 Tinbergen’s Four Questions

Theoretical biology has greatly contributed to our understanding of cooperation among unrelated individuals since the work of Charles Darwin, specifying the mechanisms and processes that have shaped the behaviors we observe today. In a similar manner, evolutionary psychology has devoted special attention to the evolution of gossip and reputation, with several studies suggesting that the evolution of gossip was tightly related with the enlargement of human groups and the appearance of several features of human sociality (Reference Barkow, Barkow, Cosmides and ToobyBarkow, 1992; Reference DunbarDunbar, 1996; Reference McAndrew, Giardini and WittekMcAndrew, 2019).

In this section, we refer to the four questions designed by Niko Reference TinbergenTinbergen (1963) to explain the evolutionary roots of animal behavior, and we use them as an analytical tool to structure our discussion about the evolution of gossip. Despite Tinbergen’s emphasis on the need for answering all questions, all four questions have been addressed only with regard to few phenomena, and gossip, as a complex behavior, is no exception. The four questions are not limited to explaining animal behavior, but they apply broadly to any characteristic in living (and even some nonliving) systems (Reference Bateson and LalandBateson & Laland, 2013).

Tinbergen pointed out that there are four fundamentally different types of questions that need to be answered in order to fully comprehend a behavior. These four questions can be asked about any feature of an organism: (1) What is it for (its adaptive function)? (2) How did it develop during the lifetime of the individual (its ontogeny)? (3) How did it evolve over the history of the species (its phylogeny)? and (4) How does it work (what are the proximate mechanisms)? (Reference Bateson and LalandBateson & Laland, 2013). Each question helps define the key features of a certain behavior or trait, and their combination is expected to provide a full account of their evolutionary roots. These four levels of analysis are complementary, not mutually exclusive: all behaviors require an explanation at each of these four levels of analysis to be fully understood.

Function (or adaptive significance – Reference NesseNesse, 2019 – or current utility – Reference Bateson and LalandBateson & Laland, 2013) refers to the evolutionary goal of a trait, defined by its effect on genetic fitness. Traits and behaviors are adaptive when their functions improve the fitness of an organism, thus making it more likely to survive and reproduce. Ontogeny refers to the process of development that makes it possible for an organism to have that trait, and phylogeny (or evolution) refers to the historical sequence whereby the trait was acquired within a biological lineage. Finally, mechanisms identify explanations at the cognitive, behavioral, or anatomical levels that make it possible for an organism to achieve this functional goal (Reference DunbarDunbar, 2009). These four levels of explanation are grouped according to the ultimate-proximate distinction (Reference MayrMayr, 1963). Ultimate explanations refer to the fitness consequences of a trait or behavior and whether it is (or is not) selected. This class of explanations addresses evolutionary function (the “why” question), whereas proximate explanations relate to the way in which that functionality is achieved, that is, the “how” question (Reference Scott-Phillips, Dickins and WestScott-Phillips et al., 2011).

Gossiping, and the resulting reputations, allows humans to adapt and adjust to the complex social environments they inhabit (Reference Emler, Giardini and WittekEmler, 2019). Different disciplines have contributed various perspectives on its evolutionary and developmental roots, functions, antecedents, consequences. The importance of gossip for the evolution of human sociality (Reference DunbarDunbar, 1996; Reference Dunbar1996) and cooperation has received considerable attention (Reference Barkow, Barkow, Cosmides and ToobyBarkow, 1992; Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a; Reference Milinski, Giardini and WittekMilinski, 2019; Reference Sommerfeld, Krambeck, Semmann and MilinskiSommerfeld et al., 2007), and several theories have been put forward to explain how gossip evolved and how it might have contributed to the evolution of cooperation in our species. Here, we use Tinbergen’s questions to understand how and why gossip might have evolved.

2.2 Tinbergen’s Four Questions Applied to Gossip

2.2.1 What Is It For?

“What is it for?” has been asked time and again about gossip. Several functions have been attributed to gossip, but it is not always possible to distinguish between functions that are mostly beneficial for the individual and functions that are also beneficial for the group. Gossip evolved because it provided some direct or indirect fitness benefits in the form of information sharing, punishment, group cohesion, and bonding: acquiring info about defectors, punishing them without being retaliated against, and creating bonds with cooperators provide fitness advantages. The first function, information acquisition, is definitely crucial for the survival of the actor who gains the information, but the spreading of the same information can also benefit the group. “Cultural learning” (e.g., Reference Baumeister, Zhang and VohsBaumeister et al., 2004) and “social learning” refer to learning ingroup norms or one’s place in a group (e.g., Reference EckertEckert, 1990; Reference Fine and RosnowFine & Rosnow, 1978; Reference Gottman, Mettetal, Gottman and ParkerGottman & Mettetal, 1986), thus reinforcing hierarchies and status differences. Knowing who is higher in status can be crucial for survival, because those higher in status are also more powerful; that is, they can mobilize resources to support or attack other group members. Reference McAndrew, Bell and GarciaMcAndrew, Bell, and Garcia (2007) argue that gossip functions as a status-enhancing mechanism, and they propose a multilevel selection perspective, meaning that a given trait, in this case the ability to gossip, evolved to fulfill both genetic and social group purposes.

Gossip allows one to acquire new and important knowledge about threats and opportunities (e.g., Reference Watkins and DanziWatkins & Danzi, 1995) by promoting strategy learning (Reference De BackerDe Backer, 2005), which is a way to learn what can be dangerous and what can be rewarding or useful in a given environment. Knowing about others is crucial for social comparison (e.g., Reference Wert and SaloveyWert & Salovey, 2004), which permits one to acquire in a relatively inexpensive way useful knowledge about whether someone is doing better or worse in the group, and behave accordingly. This form of social comparison is emotionally safer than being publicly compared to other people, and it is less impactful on one’s social standing in case the comparison is negative for the actor. Assuming an intra-group competition perspective, gossip can be regarded as an evolved strategy to compete for valuable and scarce resources by spreading either positive information about oneself, or negative information about others. Using a variety of experimental methods, Reference Hess and HagenHess and Hagen (2021) found that gossip content is specific to the context of the competition, and that allies deter negative gossip and increase expectations of reputational harm to an adversary. Their results also point out that more valuable and scarce resources cause gossip, particularly negative gossip, to intensify, a finding in accordance with previous research about strategic information spreading as a way to deflect the negative consequences of lying (Reference Giardini, Fitneva and TammGiardini et al., 2019). Not only has gossip been linked to within-group competition (Reference Hess, Hagen, Giardini and WittekHess & Hagen, 2019), but it has been considered a specific competitive tool for intra-sexual competition (Reference Davis, Vaillancourt, Arnocky, Doyel, Giardini and WittekDavis et al., 2019). Reference CampbellCampbell (2004) argued that women primarily compete through advertising (by enhancing their appearance) and through competitor derogation by using gossip (Reference VaillancourtVaillancourt, 2013) to tarnish other women’s reputations.

The second function of gossip, documented across many different kinds of groups and settings, is sanctioning, social control, or “policing” (e.g., Reference Wilson, Wilczynski, Wells, Weiser, Huber and HeyesWilson et al., 2000). Gossip is usually regarded as a low-cost form of punishment (Giardini & Conte, 2012; Reference Villatoro, Giardini and ConteVillatoro et al., 2011) that is less dangerous than physical confrontation and more effective than institutional sanctions. In contexts in which the sanctions are gradual, going from gossip to ostracism and to legal sanction (Ellickson, 2009; Reference GreifGreif, 1989), gossip represents the simplest and more frequent form of punishment that, through the threat to someone’s reputation, can police norm violations. Not only in small, close-knit communities (Reference Boehm, Giardini and WittekBoehm, 2019; Reference BrenneisBrenneis, 1984) but also in larger groups and organizations (Reference Ellwardt, Steglich and WittekEllwardt et al., 2012; Reference Wittek and WielersWittek & Wielers, 1998; Reference Yoeli, Hoffman, Rand and NowakYoeli et al., 2013), gossip functions to promote norm-abiding behavior and discourage deviance. Similarly, in groups facing forced integration, such as the Makah Indians, gossip’s function was to maintain the unity, morals, and values of the groups by exposing those who violated group norms (e.g., Reference GluckmanGluckman, 1963).

Third, gossip creates bonds among individuals. Reference DunbarDunbar (1996, Reference Dunbar2004) proposed that gossip (and language more generally) evolved to facilitate social bonding and social cohesion in the remarkably large groups that characterize human primates. “Exploitation of more predator-risky habitats requires an increase in group size; to make this possible, it is necessary both to evolve the cognitive machinery to underpin the management of the social relationships involved (essentially a larger neocortex) and to invest more time in the necessary bonding processes” (Reference DunbarDunbar, 1996, p. 103).

2.2.2 How Does Gossip Develop during the Lifetime of the Individual?

The developmental trajectory of gossip (how did it develop during the lifetime of the individual?) has received less attention, with a few notable exceptions (Reference Ingram, Giardini and WittekIngram, 2019). Gossip is a complex behavior that entails a set of different skills that develop at different times, depending on both brain- and motor-systems maturation and on exposure to social contacts. Reference Ingram, Giardini and WittekIngram (2019) proposed a sequence of developmental stages for gossip, going from a very early sensorimotor stage (0–2 years), through intuitive and operational stages, until the display of full-fledged gossip behavior around fourteen years. The ontogeny of gossip is very much related to the development of language skills that tend to be fully in place between two and four years of age, together with the ability to report the behavior of other people (Reference Den Bak and Rossden Bak & Ross, 1996). Before that, children already possess a theory of mind that allows them to interpret others’ actions as goal-directed and to report violations to third parties (Reference Tomasello and VaishTomasello & Vaish, 2013). Other elements that are required for developing this behavior are norm internalization (Reference KochanskaKochanska, 2002) and the ability to represent how one’s behavior can be evaluated by others (Reference Piazza, Bering and IngramPiazza et al., 2011). Five-year-old children are consistently more generous when they know they are being observed (Reference Shaw, Montinari and PiovesanShaw et al., 2014), and this sensitivity to the presence of observers has been linked to heightened cooperation in several studies with adult participants (Reference Manesi, Van Lange and PolletManesi et al., 2016). Two recent studies have found that five-year-old children will provide prosocial gossip by informing on a selfish peer (Reference Engelmann, Herrmann and TomaselloEngelmann et al., 2016) and that by age seven, children believe that firsthand experience is more valuable than third-party gossip (Reference Haux, Engelmann, Herrmann and TomaselloHaux et al., 2017).

2.2.3 How Did Gossip Evolve over the History of the Species?

Asking “how did gossip evolve over the history of the species?” can be tentatively answered by looking into what gossip evolved out of, and how. Tinbergen framed this as understanding how natural selection had operated in the past, providing the genetic basis for what an individual inherits (Reference Bateson and LalandBateson & Laland, 2013). Theory of mind (Reference Tomasello, Melis, Tennie, Wyman and HerrmannTomasello et al., 2012) was certainly a key player in making gossip possible, together with language abilities that coevolved with relative brain size (Reference DunbarDunbar, 1996). Attributing thoughts and goals to others, the ability cognitive scientists call “theory of mind” (Reference Premack and WoodruffPremack & Woodruff, 1978), is central to our social life. Thanks to theory of mind, humans are able to attribute thoughts, intentions, and desires to others, and use these attributions to predict, adjust to, or justify others’ behaviors. A theory of mind is crucial to attribute intentions to the target’s actions, but also to formulate expectations about the reactions of one or more receivers to what is reported. The same action, for instance failing to meet a deadline for a team project, can be interpreted as an intentional attempt to sabotage the group, as a lack of time management skills, or as an innocent mistake due to personal circumstances. The interpretation of this action and the projected consequences of gossip, however, can make it more or less worthy of transmitting. The benefits brought about by gossip in terms of social bonding can also be related to the changing circumstances in the history of the human species, such as, for instance, the enlargement of human groups. As Reference DunbarDunbar (2004, p. 103) explained:

Humans represent the most extreme point in this sequence within the primates because hominid evolution has been characterized by the exploitation of increasingly open terrestrial habitats, both of these features being associated with increased predation risk. … Language became part of this story because, at some point in hominid evolutionary history, the group size required exceeded that which could be bonded through social grooming alone; the constraint in this context was the fact that the time investment required by grooming is ultimately limited by the demands of foraging. Language enabled hominids to break through that particular glass ceiling because it allows time to be used more effectively than is possible with grooming: Speech allows us both to interact with a number of individuals simultaneously (grooming is a strictly one-on-one activity) and to exchange information about the state of our social network (lacking language, monkeys and apes are limited in their knowledge of their network by what they themselves see).

2.2.4 What Are the Proximate Causes of Gossiping?

The last question refers to the proximate mechanisms underlying the behavior. Which triggers evoke gossiping? At the neurocognitive level, gossip is supported by three neural systems, and other systems can be activated for the recognition of stimuli and the implementation of decisions (Reference IzumaIzuma, 2012; Reference Tomasello, Carpenter, Call, Behne and MollTomasello et al., 2005). The three main networks are the reward system, the mentalizing network, and the self-control system (Reference Boero, Giardini and WittekBoero, 2019). The ability to attribute intentions to others is crucial for forming evaluations, and this is complemented by the cognitive mechanisms for reward and self-control. Taken together, these mechanisms could provide evidence for the existence of specialized reputation-management abilities in humans. In order to be effective, these abilities need to be flexible and responsive to changing conditions and environments, thus requiring the involvement of several brain areas (Reference IzumaIzuma, 2012; Reference Knoch, Schneider, Schunk, Hohmann and FehrKnoch et al., 2009). Gossip has also been linked to the endocrine system, and a recent study shows that gossip increases oxytocin levels compared to emotional non-gossip conversation (Reference Brondino, Fusar-Poli and PolitiBrondino et al., 2017).

Another key cognitive mechanism involved in gossip is epistemic vigilance (Reference Mascaro and SperberMascaro & Sperber, 2009), which is the automatic tendency to care about and assess the validity of information obtained from other people. Emotions and affective states can also be considered among the proximate mechanisms of gossip behavior, given that it is fundamentally related to the well-being and adaptive success of all the individuals who are involved in gossip. Emotions play a crucial role in helping people navigate and interact with the physical, social, and cultural world (Reference Keltner and HaidtKeltner & Haidt, 1999), and negative (shame, guilt, contempt, anger) and positive (joy, enjoyment) emotions can equally contribute to explain how gossip works. In the next section we will introduce goal framing theory as a framework of the proximate mechanisms behind gossip and reputation.

3 A Goal Framing Perspective on Gossip, Reputation, and Cooperation

This section comes in three parts. We first sketch the diverging perspectives on human nature, disentangling their different views on psychological microfoundations. The second part provides a succinct summary of goal framing theory. This theory is rooted in earlier attempts to develop more accurate behavioral microfoundations (Reference Kahneman, Tversky, MacLean and ZiembaKahnemann & Tversky, 2013; Reference LindenbergLindenberg, 1981, Reference Lindenberg1985). It is best known for its application to problems of norm compliance (Reference Keizer, Lindenberg and StegKeizer et al., 2008) and now increasingly used in a variety of research domains, such as organization science (Reference PuranamPuranam, 2018), legal studies (Reference EtienneEtienne, 2011), and research on environmental behavior. For a recent review of research using the approach see Reference Do Canto, Grunert and Dutra de Barcellosdo Canto et al., 2023. Finally, we elaborate the link between goal framing theories microfoundational assumptions and the motives behind gossiping.

3.1 Coevolution of Rationality and Sociality

How gossip and reputation may affect the sustainability of cooperation crucially depends on the kind of assumptions one makes about human nature. Previous scholarship differs considerably with regard to these so-called microfoundations. Two general classes of microfoundations can be distinguished, depending on whether or not they incorporate the coevolution of rationality and sociality (Reference Lindenberg and ZafirovskiLindenberg, 2023).

Models building on assumptions of strategic rationality constitute the first class. They have in common that they assume that self-interested maximizing behavior is basic and can be used to explain how human sociality emerged (Reference CowdenCowden, 2012). Thus, basically rational choice and game theory (not rooted in evolutionary theory) are used to explain evolutionary processes (Reference Leinfellner, Leinfellner and KöhlerLeinfellner, 1998).

The second class of microfoundations is based on social rationality. Here it is assumed that human rationality and sociality coevolved. The most prominent approaches in this class come in three different versions, all focusing on a different aspect of evolutionary adaptation (Reference Lindenberg and ZafirovskiLindenberg, 2023). One emphasizes the importance of fast and frugal heuristics as a means to cope with complexity and uncertainty in the social and nonsocial environment (Reference Gigerenzer and GaissmaierGigerenzer & Gaissmaier, 2011; Reference Goldstein and GigerenzerGoldstein & Gigerenzer, 2002). Adaptation consisted not in improving the ability to carry out complex calculations based on expected probabilities, as in the theoretical axioms of strategic rationality, but in being able to react quickly in different circumstances. This can be achieved by developing and following rules of thumb, such as imitating the successful, or cooperating if the partner cooperates. A second version of social rationality focuses on preferences. It argues that in addition to self-centered preferences, human rationality adapted to the need for cooperation with nonkin, which resulted in the development of social rationality that interprets the public social sphere as an arena in which participants play games with social preferences (Homo ludens, Reference GintisGintis 2016). The foundation of the third version of social rationality is what has been called the “third speed of change” (Reference LindenbergLindenberg, 2015): humans’ situational adaptive capacity consisting in the flexible activation of mental constructs, such as goals, preferences, and heuristics (Reference Lindenberg and ZafirovskiLindenberg, 2023). This version of social rationality emphasizes flexible activation: mental constructs, goals, and motivations can change quickly, depending on the situation and the related differences and changes in the social and nonsocial environment. The changeability of the social environment requires the ability to flexibly (de)activate goals, depending on the situation. Lindenberg locates the roots of humans’ sensitivity to situationally shifting saliences in the need for dyadic co-regulation. The latter is crucial for a wide range of situations, from sharing to mutual perspective taking, joint intentionality, and collaborative learning. In the course of evolution, the adaptive advantage of dyadic co-regulation and the related capacities to put ourselves into the shoes of others facilitated the ability to co-regulate with the group as a whole and with our future self. These capacities form the basis for experiencing group membership and the related normative goal frame, as well as concern for our resources in the future and the related gain goals.

Though the three approaches to social rationality emphasize different aspects of the coevolution of sociality and rationality, they are interrelated, in that mental concepts, and thus also the use of heuristics and social preferences, need to be activated in order to become relevant as motives and cognitions guiding behavior. Integrating the three versions of social rationality approaches, goal framing theory (GFT) provides the necessary analytical tools for explaining how gossip promotes cooperation.

3.2 Goal Framing Theory

Goal framing theory can be summarized by six interrelated key assumptions (Reference Keizer, Lindenberg and StegKeizer et al., 2008; Reference Lindenberg and StegLindenberg & Steg, 2007). First, at any point in time, human cognition is dominated by a single overarching mindset. “Dominant” means that the related mindset is salient. It is in the cognitive foreground and therefore “sets the mind” by structuring the related lower-level cognitions and motivations. Overarching mindsets are also called “goal frames.” They have far-reaching consequences for what individuals pay attention to, what they value or find important, the kind of knowledge they draw on, and how they interpret a situation (Reference LindenbergLindenberg, 2015, p. 150; Reference Lindenberg and FossLindenberg & Foss, 2011).

Second, as triggers for human behavior, three types of overarching mindsets are most important: the hedonic, the gain, and the normative goal frame. The hedonic goal frame focuses on immediate satisfaction of basic needs, on feeling good right now. It is about seeking pleasure, excitement, self-esteem, and avoiding unpleasant feelings, thoughts, or events. Individuals in a hedonic goal frame focus on the present and in this sense are “myopic.” They also pay less attention to the context, such as meeting the expectations of others or acting according to some norm.

In the gain goal frame humans focus on improving or guarding their resources. The gain goal frame is about anticipating one’s future condition and therefore also implies a longer-term orientation and planning. It comes with investments and strategic behavior. When in a gain goal frame, individuals are more sensitive to changes in their resources than about how a situation feels or which kinds of behaviors would be approved or disapproved.

In the normative goal frame, the overarching mindset is “doing the right thing.” This refers to acting appropriately with regard to the specific norms of a collectivity in a given situation. The normative goal frame defines a group-oriented overarching mindset, and it is the basis for the production of collective goods. Individuals will be attentive to what they think others expect them to do. A salient normative goal frame makes individuals less sensitive to changes in personal resources or how one feels right now.

Third, as a result of the development of co-regulation during human evolution, the a priori strengths of these three goal frames differ, with the hedonic goal frame being the strongest, followed by the gain goal frame and the normative goal frame.

Fourth, the three goal frames influence each other: whenever one of them is in the cognitive foreground, the others are in the cognitive background. Individuals’ actions rarely are entirely guided by hedonic, gain, or normative concerns. When background goals are aligned with the content of the foreground goal, they may reinforce its salience. For example, as research on organizational cultures shows, work settings may be designed such that realizing profit for one’s company is strongly connected to a strong professional work ethos, a sense of commitment to one’s team, and the pleasures coming from a supportive corporate environment (Reference MichelMichel, 2011). When the background goals are in conflict with the foreground goal, they will temper the latter’s salience. For example, normative concerns may keep the temptation to realize opportunistic gain seeking at bay even in business situations where this would be possible (Reference UzziUzzi, 1996). When (one of) the background goals become so strong that it displaces the foreground goal, a frame switch is the result, with the previous foreground goal becoming a background goal itself.

Fifth, the combination of the a priori hierarchy in the strength of goal frames on the one hand, and the fact that background goals keep influencing the salience of the goal frame either by reinforcing or by tempering it has far-reaching implications. The normative goal frame, which is pivotal for sustaining cooperation, is constantly challenged by gain and hedonic background goals, making the normative goal frame inherently more brittle than the other two goal frames. It is important to realize that though inherently stronger than the normative goal frame, the gain goal frame is also subject to be sidelined by the hedonic goal frame. Hence, unless otherwise supported and constantly reinforced either by the other two goal frames, or by the social and nonsocial environments, both the gain goal and the normative goal frame will eventually decay and fade, giving way to the hedonic goal frame.

Finally, the social and nonsocial situational context – such as cultural practices, institutional arrangements, or social influence – has a strong impact on which goal frame is made salient, and which ones are relegated to or remain in the cognitive background. Goal framing theory assumes that such situational factors can overrule the influence of values (Reference Steg, Lindenberg and KeizerSteg et al., 2016) and personality (Reference Chatman and BarsadeChatman & Barsade, 1995).

In sum, GFT provides an evolutionarily grounded microfoundation that integrates the three different perspectives on social rationality that were developed as an alternative and correction to the shortcomings of models of strategic rationality. GFT not only reconciles the different claims about human nature (Homo economicus vs. Homo socialis), but also is among the very few frameworks that puts the fragility of cooperation center stage. These qualities make it particularly suitable for re-assessing the complex links between reputation, gossip, and cooperation.

3.3 A Goal Framing Perspective on Gossip

Much has been written about the causes and processes of gossip and reputation and its consequences for the sustainability of cooperation (Reference Beersma and Van KleefBeersma & Van Kleef, 2012; Reference Garfield, Schacht and PostGarfield et al., 2021; Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a; Reference Giardini, Balliet, Power, Számadó and TakácsGiardini et al., 2022; Reference Manrique, Zeidler and RobertsManrique et al., 2021; Reference Michelson and MoulyMichelson & Mouly, 2004). This research has linked gossiping to a variety of individual motives, ranging from prosocial to antisocial, as well as to all kinds of different group outcomes, ranging from cohesion enhancing to the undermining of collective efforts. The present section uses GFT to reassess this research and to develop an integrative model of the interplay between gossip, reputation, and cooperation (Reference Giardini, Wittek, Giardini and WittekGiardini & Wittek, 2019a, Reference Giardini and Wittek2019b).

Building on GFT’s assumption about the a priori hierarchy of goal frame saliences (hedonic > gain > normative), we argue that gossip is most likely performed in a hedonic goal frame. Gossip in a gain goal frame is less likely, and gossip in a normative goal frame is even less likely. It takes special conditions to evoke gossip in a gain goal frame, and more so when a normative goal frame is salient. For example, normatively motivated gossip may be a move of last resort, which will be used only if one has reason to doubt the norm violators’ sustained commitment to comply with the group’s professional and informal normative expectations.

The remainder of this section therefore explores the conditions under which gossip is hedonically motivated. This will be followed by a discussion of the special conditions under which gossip is not motivated by a salient hedonic goal frame, but by a gain or a normative goal frame.

3.3.1 The Hedonic Roots of Gossiping

Despite the surge of academic interest in gossip, systematic research into which motives trigger individual gossip behavior and “whether people gossip for different reasons in different situations” (Reference Beersma and Van KleefBeersma & Van Kleef, 2012, p. 2643) is still scarce. Reference Beersma and Van KleefBeersma and Van Kleef’s (2012) comprehensive empirical study on gossip motives distinguishes four types of motives: to enjoy, to inform/validate, to influence others negatively, and to maintain group norms. These four motives clearly relate to the three overarching goal frames. First, enjoyment triggers stimulation and therefore contributes to the realization of a hedonic goal frame. Gathering information, according to Beersma and Van Kleef, is mainly related to validating one’s own view. Being validated in what you think about others (in evaluative terms) feels good because it satisfies a fundamental need. Thus, both the enjoyment and the information motive are rooted in a salient hedonic goal frame. Third, Reference Beersma and Van KleefBeersma and Van Kleef (2012) identify negative influence as self-serving, which corresponds to a salient gain goal frame. But note that the desire to exert negative influence could also be driven by a hedonic goal frame, as saying negative things about a third party may enhance one’s feeling of superiority. Finally, the fourth motive they identify, group protection, is a normative goal.

Based on a study among 221 undergraduates at the University of Amsterdam who filled in the 22-item Motives to Gossip Questionnaire, Reference Beersma and Van KleefBeersma and Van Kleef (2012) found that the four gossip motives differed significantly in terms of their perceived importance. The most important motives were validation and information gathering, followed by enjoyment. No significant difference was found between group protection and (self-serving) negative influence. These findings suggest that hedonic goals may indeed be a more important driver of gossip than gain or normative motives, as suggested by GFT. To assess to what degree the strength of the motives varies across situations, the same sample of 221 students was randomly divided into four groups, with each group being asked to read a different scenario. The scenarios differed along two dimensions: (a) whether a colleague’s behavior violated or did not violate a workgroup helping norm, and (b) whether the receiver of the gossip was a colleague or a friend who didn’t work at the organization. Validation/information gathering was the only motive that, for all four scenarios, significantly correlated with the self-reported tendency to instigate gossip. In the condition where the receiver is a colleague, and the behavior of the other colleague was a norm violation, negative influence and group protection showed significant, though much weaker, correlations with the tendency to gossip. This suggests that the salient hedonic motive behind gossip about norm violations by other ingroup members is flanked by weaker gain and normative concerns in the cognitive background. Taken together, the patterns revealed by Beersma and Van Kleef’s study provide some circumstantial evidence for hedonic motives being one of the main proximate causes of gossiping, at least in the contemporary setting of a class of University undergraduates. Using Reference Beersma and Van KleefBeersma and Van Kleef’s (2012) scale, Reference Hartung, Krohn and PirschtatHartung et al. (2019) also found evidence for the importance of validation and information gathering. They reported that “gossiping just for fun” is as important as a motive as relationship building and protecting others from harm. They also found that social enjoyment as a self-declared motive was more important in private than in work-related situations.

The next question then becomes: what are the evolutionary roots of the link between hedonic motives and gossip? Probably the most influential argument in this context was proposed by Reference DunbarDunbar (1997), who claimed that gossip in humans is what grooming is to nonhuman primates: it builds and sustains bonds with other group members (see Section 2). These alliances may turn out to be useful as potential future sources for support or resources, but also to prevent or mitigate future threats from others. The extensive dedication to grooming – research suggests that it depends on group size and species, and can take up to 17 percent of nonhuman primates’ time – is sustained by the fact that grooming is “extremely effective at releasing endorphins. The flood of opiates triggered by being groomed (and perhaps even by the act of grooming itself) generates a sense of relaxation (grooming lowers the heart rate, reduces signs of nervousness such as scratching)” (Reference DunbarDunbar, 2004, p. 101). The evidence on human gossiping reveals many similarities, suggesting that humans experience participation in gossip episodes as a sender or receiver as an intrinsically gratifying activity that satisfies many individual needs. This includes stimulation, self-confidence, and personal bonding (Reference FosterFoster, 2004). Gossip is “fun,” triggers a “warm glow” in the participants (Reference StirlingStirling, 1956), contributes to immediate satisfaction of needs for confirmation, bonding, belonging, and is closely tied to a wide range of emotions (Reference Martinescu, Janssen, Nijstad, Giardini and WittekMartinescu et al., 2019; Reference Waddington and FletcherWaddington & Fletcher, 2005).

Unfortunately, empirical evidence on the psychoneuroendocrinological correlates of gossiping is still scarce. However, a recent study on the hormonal responses of receiving gossip showed an increase in oxytocin – which, together with the neurotransmitters endorphin, dopamine, and serotonin, is one of the triggers of feelings of happiness. This increase was unrelated to psychological characteristics of the receiver, such as empathy, autistic traits, perceived stress, or envy (Reference Brondino, Fusar-Poli and PolitiBrondino et al., 2017). In a complementary way, a series of experimental studies found that observing antisocial acts triggers negative affect, that sharing this information with others can reduce this negative affect, and that the reduction of negative affect is strongest for individuals with a prosocial orientation (Reference Feinberg, Willer, Stellar and KeltnerFeinberg et al., 2012).