Background

This scoping review focuses on the lived experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans plus (LGBT+) people as it relates to dementia, with the ‘+’ symbol indicating the broad range of additional gender and sexuality identities and experiences associated with this diverse set of communities. Specifically, this paper aims to understand what is revealed about the lived experiences of LGBT+/gender and sexuality diverse people with dementia and their care partners.

Dementia is a global public health priority, with recent estimates suggesting the number of people living with dementia at around 50 million, and projecting increases to 138 million by 2050 (World Health Organization, 2020). Dementia is a collection of disorders that affect the brain significantly enough to impair a person's ‘thinking, behaviour, and ability to perform everyday tasks’ (Dementia Australia, 2020a). Although Alzheimer's Disease is the most common form of dementia and thus the most widely known, there are a range of types, including Lewy Body dementia, vascular dementia and Parkinson's disease dementia (Alzheimer's Association, 2021). The disorders that fall under the dementia umbrella are linked through progressive changes in cognitive, behavioural, practical and emotional functioning (Alzheimer's Association, 2021), but each condition affects people differently, meaning that every person's experience of dementia is unique (World Health Organization, 2020).

While any person can develop dementia, there are some groups and communities for which the risks are heightened. For instance, dementia is particularly prevalent among older people aged 65 years and older (Dementia Australia, 2020a) with young onset dementia (onset <65 years) accounting for only 9 per cent of cases worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020). Dementia is also linked with a range of risk factors that disproportionately affect marginalised groups (Flatt et al., Reference Flatt, Johnson, Karpiak, Seidel, Larson and Brennan-Ing2018; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Reference Fredriksen-Goldsen, Jen, Bryan and Goldsen2018), including the LGBT+ community.

LGBT+ people, ageing and dementia

LGBT+ people have been found to have higher rates of cognitive impairment compared to heterosexual or cisgender people due overlapping forms of social disadvantage and the intersection of various risk factors for cognitive impairment that stem from this (Witten, Reference Witten, Westwood and Price2016; Flatt et al., Reference Flatt, Johnson, Karpiak, Seidel, Larson and Brennan-Ing2018; Scharaga et al., Reference Scharaga, Chang and Kulas2021). Such risk factors include depression and mental distress (Flatt et al., Reference Flatt, Johnson, Karpiak, Seidel, Larson and Brennan-Ing2018; Hsieh et al., Reference Hsieh, Liu and Lai2021), limited social or cognitive engagement, and stigma that creates barriers for routine health-care access, both in terms of physical services (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Reference Fredriksen-Goldsen, Jen, Bryan and Goldsen2018) and digital health platforms (Newman et al., Reference Newman, MacGibbon, Smith, Broady, Lupton, Davis, Bear, Bath, Comensoli, Cook, Duck-Chong, Ellard, Kim, Rule and Holt2020). In addition, because particular sub-populations within the LGBT+ community (particularly gay men) have been more likely to be diagnosed with HIV in many settings (Feeney, Reference Feeney2020), they also experience a heightened risk of being diagnosed with HIV-Associated Neurological Disorder (thought to affect more than 20% of people living with HIV) and HIV-Associated Dementia (which affects about 7% of people who do not take anti-HIV medication, and who are past the early stages of the disease) (Cummins et al., Reference Cummins, Waters, Aggar, Crawford, Fethney and O'Connor2018; Dementia Australia, 2020b).

The significance of life-long experiences of personal, social and systemic discrimination among LGBT+ older people with dementia, and their care partners, should also not be underestimated (Westwood, Reference Westwood2019). Having lived through decades in which their sexuality and/or gender identities were viewed as unnatural, deviant or criminal, LGBT+ people with dementia may avoid seeking out health and social care when they need it (McPhail and Fulop, Reference McPhail and Fulop2016). When they do use health services, some LGBT+ people may choose to hide their sexuality and/or gender identity to protect themselves (Birch, Reference Birch2009; Peel and McDaid, Reference Peel and McDaid2015; Harper, Reference Harper2019). They may also experience deep-seated concern about whether they will accidentally disclose their LGBT+ identity as their cognitive ability declines (Birch, Reference Birch2009; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne and Latham2015a, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b; Cousins et al., Reference Cousins, de Vries and Dening2020). In residential aged care settings, staff may presume that LGBT+ older people are cisgender or heterosexual, or may view them as no longer having a gender or sexuality identity at all, which can be anticipated and experienced as distressing (Peel et al., Reference Peel, Taylor and Harding2016).

Overall, the literature on LGBT+ experiences of dementia is scarce. Nevertheless, research on LGBT+ ageing helps to further build an understanding of some of the challenges they face in terms of health and social care. The United Kingdom-focused scoping review by Kneale et al. (Reference Kneale, Henley, Thomas and French2021), for example, found that older LGBT+ people are deeply affected by the hostility and discrimination to which they were subjected during their earlier years, which resulted in significant physical and mental health inequalities. Kneale et al. (Reference Kneale, Henley, Thomas and French2021: 493) describe social care environments as the ‘focal point for inequalities’ and characterise formal care services – broadly, those in which individuals receive care services from paid workers, such as in a residential aged care facility – as spaces that ‘severely [compromise] the identity and relationships that older [LGBT+] people [have] developed’. The scoping review by Kneale et al. (Reference Kneale, Henley, Thomas and French2021) also affirmed the importance of the social groups with which some older LGBT+ people have surrounded themselves, framing these as a protective factor against the social isolation associated with discrimination.

The findings were similar in another recent scoping review on LGBT+ older people's experiences of health care, which focused on end-of-life care and gathered literature from studies published around the world. Stinchcombe et al. (Reference Stinchcombe, Smallbone, Wilson and Kortes-Miller2017) found fear of, and actual experience of, mistreatment and discrimination to be a pressing concern for ageing LGBT+ people. Concerns around lack of equality and inclusivity were echoed in the scoping review by Lecompte et al. (Reference Lecompte, Ducharme, Beauchamp and Couture2021) on LGBT+ older adults' experiences with health and social care services, in Canada or countries with similar legislation. The authors argue that system-level change is required for equality and inclusion to become a reality in health and social care settings (Lecompte et al., Reference Lecompte, Ducharme, Beauchamp and Couture2021).

Other complexities raised in the literature include transgender people in formal care settings ‘forgetting’ that they have transitioned, or starting to associate with gender identity in a different way (Marshall et al., Reference Marshall, Cooper and Rudnick2015; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne and Latham2015a, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b; Baril and Silverman, Reference Baril and Silverman2022). There are considerable differences in the way this is conceptually framed in the literature. Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Cooper and Rudnick2015: 112), for example, position this as a sign of ‘gender confusion’. In the case study they present, Marshall et al. (Reference Marshall, Cooper and Rudnick2015: 112) discussed an older trans person who began to display gender-fluid preferences while in a residential aged care facility, writing that this person was ‘no longer able to express a consistent gender preference due to moderate dementia’. This perspective has been strongly critiqued in Baril and Silverman (Reference Baril and Silverman2022), who argue that expressions of gender fluidity among trans people with dementia should be supported, not pathologised. Baril and Silverman (Reference Baril and Silverman2022) go on to suggest that using terms like ‘gender confusion’ are ageist and ableist. Indeed, trans individuals have long had to endure harmful assumptions that they are simply ‘confused about their identity’ (Totton and Rios, Reference Totton and Rios2021: 511) and are not who they say they are. Withall (Reference Withall2014) notes that trans people with dementia may be particularly vulnerable to cisgenderist pressure within formal care services if they are socially isolated, perhaps having lost or ended contact with those family and friends who did not affirm their gender identity. Withall (Reference Withall2014) argues that this adds to the importance of setting up advanced health-care directives. As a result of cumulative stigma and disadvantage, there is a sense of anticipatory dread among many LGBT+ people, with some having described a dementia diagnosis as their ‘worst fear’ (Price, Reference Price2012: 521).

Whilst the experience of dementia is more common in the older population, it remains unclear how the lived experience of dementia affects experiences of ageing and vice versa. This scoping review seeks to understand what the literature reveals about the lived experience of LGBT+ people, and/or their partners, after receiving a dementia diagnosis. We also consider the methods and research partnerships that have been used to investigate these lived experiences. This is because we are interested not just in what is known about this subject matter, but how it is known, in terms of the methods used.

Method

Scoping review framework

This scoping review was conducted in consultation with ACON, an organisation based in New South Wales (NSW), committed to promoting the health of gender and sexuality diverse communities, and Positive Life, a peer-run representative body for people living with HIV (also in NSW). Scoping reviews identify the breadth of existing literature and summarise what is already known about the topic (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005). This approach differs from systematic reviews in several ways: it is smaller in scale and thus can be conducted more quickly; it does not usually comment on the quality of the studies being synthesised; and is often a preliminary investigation seeking to understand whether and how a certain issue has been addressed in the literature. Since our intention was to conduct an initial exploration of what had been published on LGBT+ experiences of dementia, a scoping review was deemed ideal.

We used Arksey and O'Malley's (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) five stages, including: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) selection of relevant studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarising and reporting the results. As per stage 1 in this framework, our research question was refined over several weeks of discussion between members of the research team. Initially, we planned to investigate what is known from the literature about the lived experiences of LGBT+/gender and sexuality diverse people with dementia and their care partners. We already suspected, based on a preliminary scan of the literature, that studies which foregrounded the voices of LGBT+ people would be scarce. Upon further deliberation, however, it became clear that we also wanted to investigate how gender and sexuality diverse people with dementia and their care partners were being approached and engaged by researchers. We wanted to know how inclusive these methods were, including whether the researchers had partnered or consulted with LGBT+ organisations to ensure the relevance, appropriateness and sensitivity of their methods. This was in part motivated by other scholarship showing the importance of innovative research methods for engaging in meaningful ways with participants who have dementia (Phillipson and Hammond, Reference Phillipson and Hammond2018).

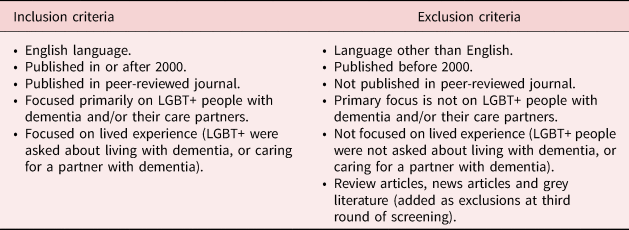

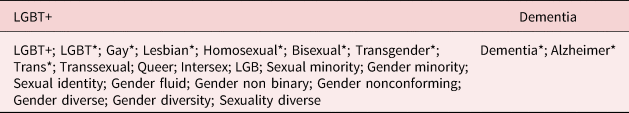

In stage 2, consultation with the research team including key partner organisations and observations of other sociological scoping reviews (Botfield et al., Reference Botfield, Newman and Zwi2016; Bell et al., Reference Bell, Aggleton, Ward and Maher2017; Phillipson and Hammond, Reference Phillipson and Hammond2018; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Strnadová, Watfern, Pebdani, Bateson, Loblinzk, Guy and Newmanin press) helped us to decide how to identify relevant studies. Searches were first conducted on electronic academic databases: Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE (including records published in PubMed), PsycINFO, ProQuest and CINAHL. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this search, as well as the key search terms, are provided in Tables 1 and 2. The initial search imported 1,355 records. A total of 852 records remained after removing duplicates, first by using the automatic EndNote function, and then by removing the remaining copies manually.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 2. Search terms

Given our interest in reviewing contemporary research on our topic, we limited our review to papers published from 2000 to 2021. This approach has been used elsewhere to ensure recency and relevance of results (Phillipson and Hammond, Reference Phillipson and Hammond2018).

Stage 3 of the review involved multiple rounds of screening. A simplified version of this process is shown in Figure 1, and was based on the PRISMA protocol for systematic reviews (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). The first round of screening, conducted by IC, removed irrelevant records based on title, leaving 203 records. These records were then screened based on title and abstract, after which 65 records remained. The third round of screening involved LS and IC independently selecting which articles they felt were relevant and irrelevant based on a closer analysis of titles and abstracts. Thirty-five of the remaining articles were eliminated because their focus was too broad or because the experiences of LGBT+ people with dementia and/or their care partners was not the focus of the article.

Figure 1. PRISMA chart of the research process (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

IC then sourced the full-text PDFs of the remaining 30 records in order to search reference lists for other potential inclusions. Six new records were identified from this reference list search, bringing the total of remaining records back up to 36. IC accessed the full text of these records so that the fourth and final round of screening could commence. At this point, the decision was made by the authors to screen out grey literature and review articles, meaning that several records could be removed immediately. We made this decision because we wanted our review to highlight where researchers had directed their attention and resources, and what had been published in peer-reviewed journals as a result. We have included relevant grey literature in the Background section of this paper to contextualise what has been written outside the context of higher education research.

LS and IC then carefully read the remaining full-text articles (N = 14). Through further discussion, another inclusion criterion was added: only sources that allowed LGBT+ people to directly share their experience relating to dementia were to be considered. The articles did not need to follow a qualitative methodology necessarily, but participants needed to have been given an opportunity to provide their own feedback on how dementia was experienced in their lives. Seven records were deemed eligible.

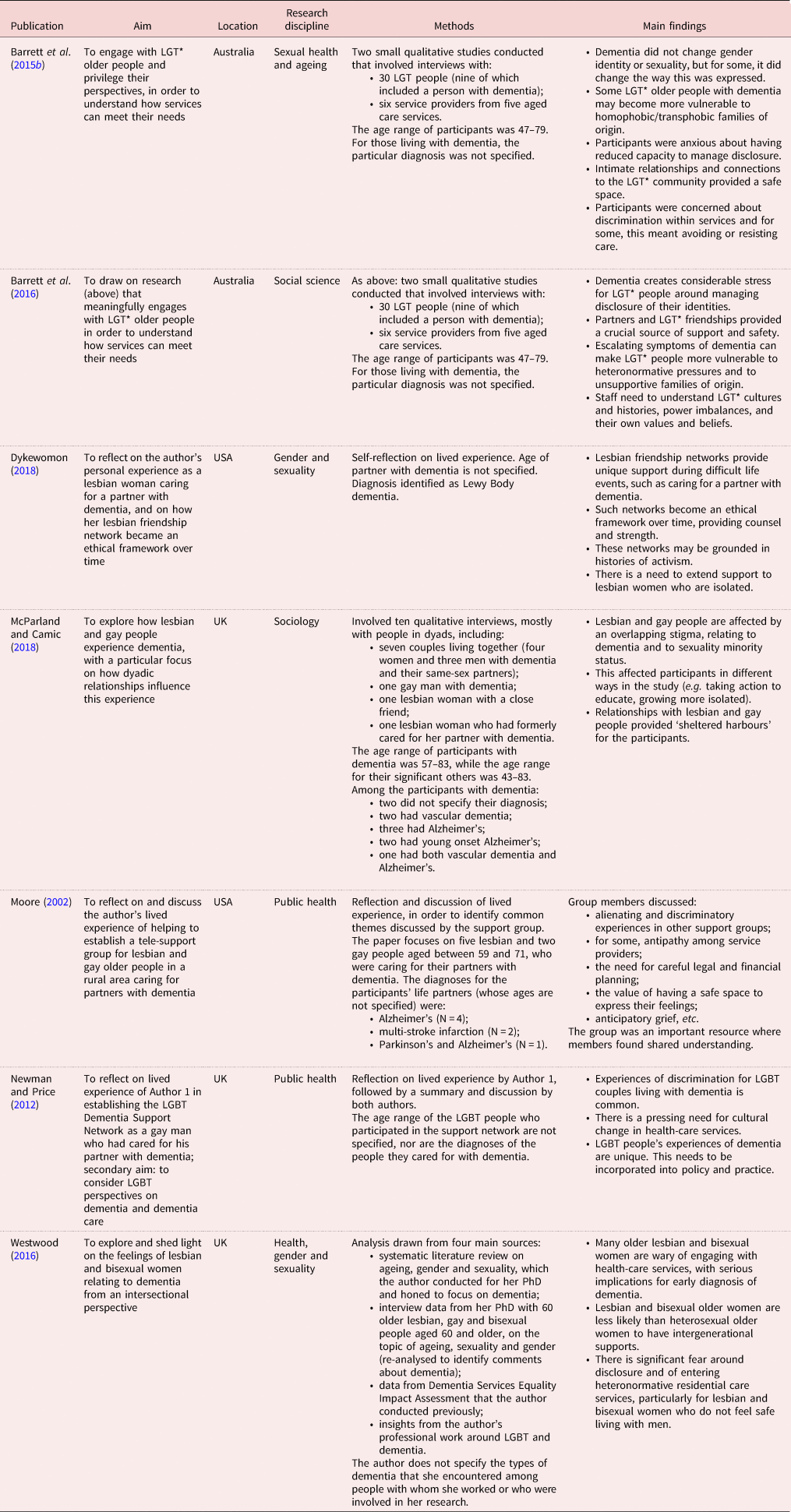

IC was responsible for charting the final records (stage 4). A simplified version of the final chart has been included in Table 3. The tabulation was reviewed by LS, and then by the wider research team (including representatives from ACON), who were also sent the full text of the included papers. Each person was invited to: (a) provide their thoughts around the results, including key themes; and (b) offer any additional papers or reports they felt would help to frame the Background and Discussion sections of the paper.

Table 3. Simplified tabulation of results

Notes: UK: United Kingdom. USA: United States of America.

Stage 5 of Arksey and O'Malley's (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) scoping review framework, which yielded the results of this study, will now be outlined.

Collating, summarising and reporting the results

Our analysis of the results was based on the primary research question of this scoping review – what is known from the literature about the lived experiences of LGBT+/gender and sexuality diverse people with dementia? – as well as our related, secondary research question, which focused on methods. To address the overarching research question, LS and IC applied Braun and Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2021a, Reference Braun and Clarke2021b) framework for reflexive thematic analysis (TA). According to Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), TA should be guided by the following process: (a) familiarising oneself with the data; (b) generating initial codes; (c) looking for themes; (d) reviewing and refining those themes; (e) defining and naming the final themes; and (f) producing the report (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Reflexive TA is an iterative process in which the researcher is constantly returning to, reflecting on and making meaning from the data. As a result, the researcher is able to develop nuanced themes that each tell a story about the dataset (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021a, Reference Braun and Clarke2021b).

For our review, familiarising oneself with the data meant reading, re-reading, reflecting and revisiting the final papers to ensure a thorough familiarity with them. LS and IC then moved to the coding phase of analysis. Although having two or more coders is not necessary in reflexive TA – as researcher subjectivity is viewed by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021a, Reference Braun and Clarke2021b) as a tool for making meaning, rather than a problem to avoid – we found it useful for our review. In essence, this approach meant that LS and IC could compare, discuss and support one another's reflexivity about the data, which proved pivotal for building our themes.

LS and IC read each of the seven papers separately to identify what they felt were the main ideas across the dataset, which became our codes. Then, again independently, LS and IC grouped these ideas under initial themes. During this phase, they realised none of the papers included the perspectives of people who identified as intersex or queer. As such, these acronyms were dropped from LGBT+ to avoid misrepresenting the findings (Westwood, Reference Westwood2020). The next phase of analysis involved LS and IC coming together to discuss what they had found. Over several meetings, they created a consolidated, revised list of initial themes: Resisting services; Fear related to disclosure; Discrimination; Grief and loss; Framing of dementia; and Love and connection.

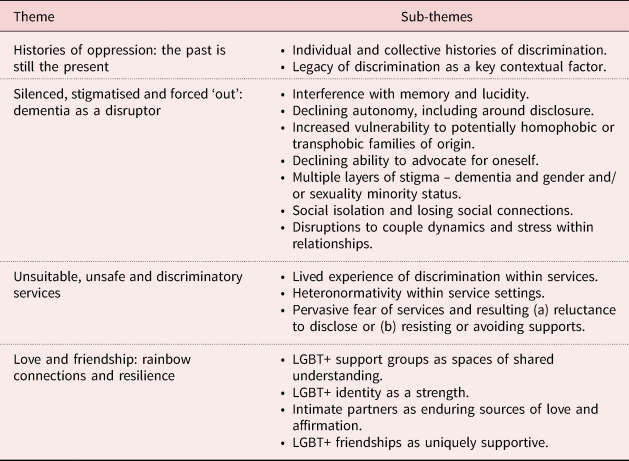

The fourth stage of reflexive TA involves immersing oneself in the data once more. Tentative themes are interrogated, refined and strengthened until they become ‘like multi-faceted crystals [… that] capture multiple observations or facets’ (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021a, Reference Braun and Clarke2021b: 340). Using NVivo 12 software, LS and IC went through the papers and coded them deductively based on the initial themes they had developed. Throughout this process, those initial themes were expanded upon, collapsed and altered based on analysis and reflection. The authors then came together to discuss their analyses and, after consultation with the wider research team, they decided upon four final themes (summarised in Table 4 and presented in the Findings).

Table 4. Themes and sub-themes in the literature

During the consultation with the wider research team, FD stressed that the Findings section should also include a summary of recommendations in the literature on how LGBT+ people with dementia (or their partners) could be better supported. He argued that this would be of practical use for LGBT+ community organisations like the one for which he works. Therefore, in the Findings, we include a brief overview of recommendations synthesised from the seven papers. We argue that this inclusion in our paper is not only appropriate, but serves to illustrate our commitment to collaboration with partners outside the university context and to inter-disciplinary approaches.

Analysing the methods used across the seven papers was a comparatively simpler process. IC tabulated details relating to the methods in each paper, such as when and where studies took place, the demographics of participants, how LGBT+ individuals were asked to share their lived experience relating to dementia and whether the authors described any partnerships with LGBT+ community organisations.

Findings

Histories of oppression: the past is still present

The literature makes clear that LGBT+ experience of dementia cannot be understood without first understanding the lifetimes of oppression that older gender and sexuality diverse people have carried with them. For decades, members of this community were ‘treated as mentally ill’, lost or were denied jobs, were ‘forced to undergo psychiatric “cures” including electric shock treatment’ (Westwood, Reference Westwood2016: 1498). They were also rejected by their families who ‘did not value who they were’ (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b: 35), and for many, learned to hide their identities to ensure survival (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). Fear around and memories of discrimination, stigma and violence have shaped the way many older LGBT+ people interact with and view the world around them (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b).

These lifetimes of oppression have resulted in LGBT+ older people reporting more social isolation than their heterosexual, cisgender peers (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016). Although many LGBT+ older people will have built strong families of choice, they are at the same time more likely to be single, less likely to have adult children who can care for them (Westwood, Reference Westwood2016) and less likely to report positive relationships with families of origin (Westwood, Reference Westwood2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). This tapestry of disadvantage creates a complex backdrop for what it is like for LGBT+ people to also experience living with dementia.

Silenced, stigmatised and forced ‘out’: dementia as a disruptor

Dementia symptoms such as memory loss (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018) and disorientation (Moore, Reference Moore2002) were discussed in the literature as potent sources of anxiety, because of the way they could jeopardise and undermine control and autonomy (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). In some cases, this meant people had increasingly less control over whether and how they disclosed their sexuality and/or gender diverse identity, which created immense stress (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). This appeared to be felt by LGBT+ people with dementia and their partners alike, some of whom found themselves ‘outed’ by the person they love (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016). As well, for older trans people with dementia, the very act of being in care and having their bodies witnessed by strangers could eliminate their ability to control which parts of their identity are shared (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b). The literature does not go into detail about how different types of dementia might interrupt and upend people's lives in distinct ways. Dykewomon (Reference Dykewomon2018) is an exception, whose partner anticipated the ‘Parkinson's-like symptoms’ of her Lewy Body dementia with a profound sense of dread.

Another source of anxiety and distress revolved around what would (or did) happen to LGBT+ people with dementia as their decision-making capabilities diminished (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b). For some, a reduced ability to make their own decisions meant that biological family members could re-enter their lives, placing power in the hands of those with potentially heteronormative or cisgenderist views (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016). Although some LGBT+ people with dementia had partners and families of choice to support them, their importance was not always understood by relatives or by staff (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b). In Moore (Reference Moore2002: 31), one care partner recalled ‘puzzled looks, halting questions, and uncomfortable attitudes’ from hospital staff, and being repeatedly asked questions like ‘[are] there any family members we should be talking to?’ Single LGBT+ people with dementia (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018) and care partners with little or no networks of support (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Dykewomon, Reference Dykewomon2018) were highlighted as especially vulnerable. Reflecting on this point, Dykewomon (Reference Dykewomon2018: 100) wondered ‘what … people do without a close local network, without friends who have the commitment, time, and money to stay with them’.

Dementia could also interfere in the way LGBT+ people saw themselves or how they were perceived by others. Barrett et al. (Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b) and McParland and Camic (Reference McParland and Camic2018) described the overlapping stigma facing LGBT+ people with dementia and their care partners, one that relates both to cognitive impairment and to being a gender and/or sexuality minority. One participant in McParland and Camic's (Reference McParland and Camic2018: 463) study explained of her dementia diagnosis, ‘[before] I couldn't say the word because, because I was ashamed of it’. Several authors reported that participants grew increasingly isolated as their dementia, or the dementia of their partner, progressed (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). Others pointed out that for older LGBT+ people, friends of a similar age in their family of choice may be battling their own health concerns around ageing (Westwood, Reference Westwood2016), and thus may be less available to support the person with dementia or their care partner. Troublingly, relationships that affirm LGBT+ identity appear to become less available as dementia progresses (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). In Barrett et al. (Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b: 36), one participant said her friends ‘don't know what to do, so they stay away’. These authors noted that LGBT+ communities would benefit from being educated on the importance of continuing to reach out to their peers after a dementia diagnosis (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b).

Other forms of interference wrought by dementia were related to intimate partnerships, and how the dynamics between couples may become disrupted by cognitive impairment. In addition to the stress of partners having to fight for recognition and fair treatment (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Newman and Price, Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018), care partners acknowledged the difficulty of managing a rising ‘sea of needs’ and multiple roles – supporter, advocate and carer, as well as lover and life partner (Moore, Reference Moore2002; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018: 468). In Moore (Reference Moore2002: 35), partners described different ways that dementia had impacted their loved one's behaviour and thus their day-to-day lives: ‘sleeping, agitation, possible violent outbursts, repetitive behaviors or verbalizations, and dilemmas with personal care – dressing, eating, bathing, and incontinence’. Importantly, the difficulty wrought by these ‘re-calibrations’ (McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018: 468) was framed as coming from dementia itself, not the relationship that LGBT+ couples shared with one another (McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). Some partners had to wrestle with these changing dynamics while also being wrapped in anticipatory grief, a phenomenon that is also discussed in broader dementia literature (Garand et al., Reference Garand, Lingler, Deardorf, Dekosky, Schulz, Reynolds and Amanda2012; Kobiske et al., Reference Kobiske, Bekhet, Garnier-Villarreal and Frenn2019). In McParland and Camic (Reference McParland and Camic2018), participants spoke of increasing loneliness as they watched their partners' cognitive ability decline or imagined futures without them. In her personal essay, Dykewomon (Reference Dykewomon2018: 98) reflected on her partner's wishes to end her life after being diagnosed with Lewy Body dementia (her partner ultimately died of natural causes):

Susan and I talked about it. I asked her how she would know it was time, and she came up with, ‘when I can't unload the dishwasher anymore’. I said she would have to trust me to let her know … She said, ‘if you tell me it's the month, the week, the day, I will trust you’. We cried.

Unsuitable, unsafe and discriminatory services

For older LGBT+ people with dementia and their partners, systemic discrimination was not relegated to their past (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Newman and Price, Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016; Dykewomon, Reference Dykewomon2018; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). When interacting with health and social care services, LGBT+ people said their care needs, histories, families and relationships were still not well understood (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Newman and Price, Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). A participant in Barrett et al. (Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b: 36) recalled that services seemed to invent reasons not to accept his partner for care once their sexuality was made known. Elsewhere in the same paper, several trans interviewees said they ‘stopped revealing their trans status after being refused services’. Similarly in McParland and Camic (Reference McParland and Camic2018: 462), it was suggested to one participant that her partner's dementia could be ‘linked to her lesbianism’. In Newman and Price (Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012: 184), one of the care partners discussed his own experience as a carer: ‘I can honestly say… that no service provider related to me in a straightforward or empathic way.’ Even within the private homes of LGBT+ couples, the threat of discrimination could still be felt. When asked about care workers entering her home, a participant in McParland and Camic (Reference McParland and Camic2018: 469) said ‘they're not necessarily telling the truth [about not being homophobic], so how do we know that we're safe?’

Moore (Reference Moore2002: 26) warned against attributing instances such as these to individual attitudes, writing that ‘nearly all services for older adults have been created within a heterosexual framework’. In these environments, people who are gender and sexuality diverse were made to feel invisible, as their identities and their support needs went unseen (Moore, Reference Moore2002; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). Westwood (Reference Westwood2016) drew in an intersectional lens to argue that lesbian and bisexual women are especially vulnerable to being made invisible, especially if they are also women of colour.

These experiences often culminated in a persistent fear of health and social care services, meaning that some chose to hide their gender and sexuality diverse identity from staff and from providers (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). Others responded to anticipated discrimination or fears of sub-par care by delaying or resisting services Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018; Di Lorito et al., Reference Di Lorito, Bosco, Peel, Hinchliff, Dening, Calasanti, de Vries, Cutler, Fredriksen-Goldsen and Harwoodin press). As Westwood (Reference Westwood2016) notes, such delays could preclude LGBT+ people from receiving vital early intervention supports. In addition, the kinds of services that LGBT+ people with dementia and their partners want or need – gender and sexuality diverse support groups and facilities, for example – are not always available (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018) or are denied to those who seek them (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne and Latham2015a, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b).

Love and friendship: rainbow connections and resilience

Crucially, across all seven papers in this review, love and connection within the LGBT+ community and from intimate partners was framed as a significant protective factor. Partners acted as ‘sheltered harbours’ (McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018: 466) that could affirm identity and personhood (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018) and protect against loneliness (McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). In several of the studies, engaging with other members of the LGBT+ community – such as through gender and sexuality diverse support groups, or spending time with LGBT+ friends – was found to provide spaces where lived experience did not have to be justified, concealed or explained (Moore, Reference Moore2002; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018).

Having presented the four themes that our reflexive TA generated, we now offer a summary of recommendations synthesised from the findings across the seven papers, which centre on how LGBT+ people with dementia and/or their partners could be better supported.

Recommendations in the literature

Overall, authors advocated for greater inclusivity and understanding among service providers, as well as improved access to supports that were specifically targeted at gender and sexuality diverse communities. Barrett et al. (Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016), for example, identified the importance of health and social care staff advocating for LGBT+ clients with dementia. This was described as particularly necessary for those who do not have someone in their life who supports them, for whom homophobic, biphobic or transphobic family members may pose a threat. These individuals may also be at greater risk of experiencing elder abuse (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016) by virtue of their social isolation and complex support needs. Indeed, according to the final report from the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (2021: 140) in Australia (where the primary authors of this paper are based), elder abuse in the aged care sector is alarmingly common and a ‘source of national shame’.

Another key recommendation was for staff training to provide greater understanding of LGBT+ histories, contemporary experiences, needs, values and cultures (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016), although such education would, we argue, also need to account for diversity within and among the LGBT+ community as well. Other suggestions included: better access to social supports for LGBT+ people with dementia and their partners, particularly their links to the LGBT+ community (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; Dykewomon, Reference Dykewomon2018); increased access to gender and sexuality diverse support groups (Moore, Reference Moore2002); and encouraging LGBT+ people with dementia to create advanced care directives (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016). As well, McParland and Camic (Reference McParland and Camic2018) and Newman and Price (Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012) highlighted the need for services to actively signal safety by displaying LGBT+ symbols and other visible messages of inclusion. Many of these recommendations focused on the need to disrupt systemic heteronormativity and to build a culture of shared understanding, inclusion and support for gender and sexuality diverse people.

Furthermore, reminiscence activities were also suggested as useful ways to champion the lives and relationships of LGBT+ people with dementia (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). During these activities, a person with dementia is guided to reflect on their previous experiences, focusing on memories of people, places and things that matter to them. This is believed to maintain connections to personhood (Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Hunter, Murphy, Casey, Devane, Smyth, Dempsey, Murphy, Jordan and O'Shea2014), although reminiscence in a group context can also be exclusionary and in some cases heteronormative (Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie2009). For example, among some of the participants in McParland and Camic's (Reference McParland and Camic2018) study, reminiscence was found to connect people with dementia to aspects of their identity, which in turn was important for their partners. Yet, authors were careful to point out the complexity of reminiscence. According to Barrett et al. (Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016: 105), reminiscence groups and life-story work presumes ‘that people feel safe sharing their history and that their history is a positive one’. There is no small risk in delving into the histories of LGBT+ people, potentially bringing up traumatic memories (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016), or prompting them to ‘unintentionally “out” themselves in … unsafe environments’ (McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018: 472). These authors do not provide explicit instructions on a pathway forward. Rather, they write that creating inclusive service environments built on shared understanding is a crucial first step (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018).

Methods used in the literature

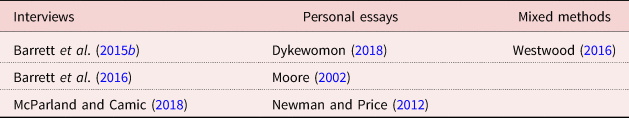

Our analysis of methods used in the literature suggests that very little research has worked collaboratively with LGBT+ people with dementia to support them to tell their own stories (see Table 5). Only three of the papers across two studies (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018) reported data drawn from qualitative interviews with LGBT+ people with dementia. Three other papers were personal essays of lived experience – two were written by LGBT+-identifying authors who had cared for partners with dementia (Newman and Price, Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012; Dykewomon, Reference Dykewomon2018), and one was written by a person who had facilitated a support group for lesbian and gay carers (Moore, Reference Moore2002). None of these personal essays was written by an LGBT+ person with dementia. As such, we can observe how scarcely the perspectives of LGBT+ people with dementia themselves are found in recent, English-language literature.

Table 5. Methods used

Only one study discussed in two of the papers (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016) described research partnerships with LGBT+ organisations. Part of the study involved collaborating with the Gender Centre NSW, Transgender Victoria and FTM Shed. Barrett et al. (Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016) do not, however, provide a detailed account of the extent to which these partnerships informed the research process. McParland and Camic (Reference McParland and Camic2018) also mentioned engagement with LGBT+ organisations, but this appeared to be for recruitment purposes. Partnerships were marked not applicable for the three personal essays (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Newman and Price, Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012; Dykewomon, Reference Dykewomon2018).

None of the studies used innovative methods for engaging LGBT+ people with dementia. By innovative, we mean methods that are engaging for people who find it difficult to communicate verbally or through writing, such as those that incorporate art-making (Smith and Phillipson, Reference Smith and Phillipson2021). The implications of this will be addressed in the Discussion section of this paper.

Discussion

In this paper, we set out to illuminate the lived experience of dementia as described by LGBT+ people with dementia and their care partners. In the seven papers reviewed, the concept of overlapping disadvantage facing LGBT+ people with dementia – relating to cognitive impairment and minority population status – was frequently referenced. Some of the challenges faced by LGBT+ people with dementia and their care partners are also discussed in the broader dementia literature, including: cognitive decline having a fundamental impact on autonomy (Wolfe et al., Reference Wolfe, Greenhill, Butchard and Day2021), stigma and resulting social isolation (Riley et al., Reference Riley, Burgener and Buckwalter2014), and disruption of couple dynamics through care-giver burden and anticipatory grief (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Ho, Cheung, Lam and Tse2018). However, what the papers in this review show is that for gender and sexuality diverse people, these issues are compounded by other challenges that are unique to LGBT+ older people. Not only do LGBT+ people with dementia have to contend with diminishing control over how they live their lives, they must also wrestle with having less control over whether or how they disclose their gender and/or sexuality identity. They also know that if they do, this disclosure potentially exposes them to discrimination, reminding them of histories of such discrimination. As well, not only are the partners of LGBT+ people with dementia having to grapple with care-giver burden and anticipatory grief – they are also often having to fight for their relationships to be recognised and valued at all.

The literature also emphatically asserts that diverse gender and sexuality identities are sources of strength, and that the vulnerability associated with being LGBT+ stems from the heteronormative and cisgenderist attitudes of others (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Newman and Price, Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). Dementia has the potential to amplify vulnerability by affecting the capacity of LGBT+ people to stay connected and to live autonomously (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; Westwood, Reference Westwood2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). There needs to be greater emphasis in the literature on how LGBT+ people living with dementia can continue to affirm their sexuality and/or gender identity, within themselves and through their relationships with others.

It should be noted that other aspects of intersectional identity were rarely discussed in the literature. For example, there was no discussion about the distinct experiences of LGBT+ people with dementia who were also First Nations people, from migrant or refugee backgrounds, or sustained socio-economic disadvantage. In addition, there was an absence of investigation into how dementia may be experienced differently for LGBT+ people with other stigmatised health conditions, like HIV/AIDS (or HIV-Associated Dementia).

Indeed, the gaps and silences across the literature in this review are among the most revealing of our findings. Firstly, we wish to note that across the papers in our study, the distribution of who was included was far from even, with most participants identifying as lesbian or as gay men (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Newman and Price, Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012; Dykewomon, Reference Dykewomon2018; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018). Only one study included people who were trans, although the exact number of trans interviewees in this study is not specified, and it is not clear whether any had been diagnosed with dementia (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016). None focused explicitly on people who were intersex, non-binary or queer, despite these being search terms we used. We have therefore struggled to capture the nuance and distinctions between the experiences of lesbians, gay men, bisexual and trans people with dementia in our review, because the papers we examined did not analyse these differences. We will return to this point in the Limitations section of this paper.

Another major issue was how the perspectives of LGBT+ people with dementia themselves seem almost entirely absent from literature about them. That only seven papers met our inclusion criteria for this review speaks volumes about how rarely LGBT+ people are sought out in scholarly dementia research to share their lived experience. Often too, when LGBT+ experiences of dementia are a focal point in peer-reviewed research, it is the care partner who is speaking (Newman and Price, Reference Newman, Price, Ward, Rivers and Sutherland2012; Dykewomon, Reference Dykewomon2018) or being spoken to (Moore, Reference Moore2002), not the person with dementia. While the lived experiences of both groups are important and interrelated, they are also distinct. It is imperative that future research supports LGBT+ people with dementia to share their stories, rather than having their stories told for them.

Even authors who engaged with LGBT+ people with dementia as part of their methodology, by including them in interviews (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018), relied almost exclusively on talk-based methods. There are significant limitations in using these research methods with people who have dementia, for whom verbal communication can be highly challenging (Phillipson and Hammond, Reference Phillipson and Hammond2018). More innovative, creative methods have been found useful for people with dementia (Phillipson and Hammond, Reference Phillipson and Hammond2018; Brennan-Horley et al., Reference Brennan-Horley, Phillipson, Smith, Frost, Ward, Clark and Phillipson2021; Smith and Phillipson, Reference Smith and Phillipson2021; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Phillipson and Knight2021) and other cognitive impairments (Mah et al., Reference Mah, Gladstone, King, Reed and Hartman2020). In a scoping review by Phillipson and Hammond (Reference Phillipson and Hammond2018), photovoice was found to be the most common innovative method for engaging people with dementia in research. The authors argue that innovative, creative methods such as photovoice, video recording and Talking Mats have been effective in supporting the inclusion of people with dementia and are strengths-based in their design, used in recognition that people with dementia can be ‘active, insightful, and meaningful contributors’ to research (Phillipson and Hammond, Reference Phillipson and Hammond2018: 10).

In addition, while several papers argued for greater understanding among service providers around LGBT+ experiences and needs (Moore, Reference Moore2002; Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016; McParland and Camic, Reference McParland and Camic2018), few mentioned whether they had collaborated with LGBT+ organisations as part of their research process (Barrett et al., Reference Barrett, Crameri, Lambourne, Latham and Whyte2015b, Reference Barrett, Crameri, Latham, Whyte, Lambourne, Westwood and Price2016). These organisations hold valuable expertise in the lived experiences of their own communities (Hafford-Letchfield et al., Reference Hafford-Letchfield, Simpson, Willis and Almack2018) and must be engaged through meaningful forms of collaboration and consultation, so as to ensure that research is conducted in culturally appropriate and relevant ways. ACON and Positive Life, for example, have produced comprehensive reports and guidelines on other issues that relate to LGBT+ health (ACON and NADA, 2019; Feeney, Reference Feeney2020). There is an urgent need for future studies that collaborate with LGBT+ organisations to understand what would support gender and sexuality diverse people with dementia and their partners. LGBT+ people may also be selective about who they share their stories with and are traditionally a ‘hard to reach’ population in terms of study participation (Lucassen et al., Reference Lucassen, Fleming and Merry2017; Price, Reference Price2010). As such, recruiting members of this community to talk about their experiences will likely hinge on building trust with respected LGBT+ community organisations first (Newman et al., Reference Newman, MacGibbon, Smith, Broady, Lupton, Davis, Bear, Bath, Comensoli, Cook, Duck-Chong, Ellard, Kim, Rule and Holt2020).

Limitations and recommendations for future research

According to Arksey and O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005), scoping reviews do not usually assess the quality of the studies they analyse. Given that Arksey and O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) was the methodological framework we followed for our own scoping review, we did not look for or notate the limitations of the studies in our final selection. Arguably, systematically documenting these limitations and including them in our results would have added further depth to our paper. Indeed, future studies that highlight limitations of existing research on LGBT+ people and their experiences related to dementia would be a welcome addition to the literature.

Another issue we wish to address is our use of TA to highlight common patterns across such a small number of papers, two of which were based on the same study. While we recognise that this may be perceived as a limitation, we also wish to underline the qualitative nature of this review, and how this is well-aligned with reflexive TA. In one of their recent methodology papers, Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021b) write that ‘determining a participant group/data set size for TA is not as simple as identifying the “correct number” of participants or data items’. The level of detail and insight in the dataset, the researcher's goals in conducting the analysis, and the breadth or narrowness of the research question, are among the factors that should guide scholars on appropriate sample size (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021b). Given the richness of our seven articles, the specificity of our research question and our motivation for conducting the research – which was concerned not with the quantity of papers we would yield, but with the depth of insights we could glean about people's lived experience – we believe reflexive TA was a suitable methodology for this review. It is also relevant to note that other qualitative scoping reviews have used TA to explore patterns across a small number of papers (Nicholas et al., Reference Nicholas, Newman, Botfield, Terry, Bateson and Aggleton2020; Lecompte et al., Reference Lecompte, Ducharme, Beauchamp and Couture2021). For instance, in the scoping review by Nicholas et al. (Reference Nicholas, Newman, Botfield, Terry, Bateson and Aggleton2020), about men's perspectives on vasectomy, TA was applied to ten studies that met their inclusion criteria.

Finally, as our scoping review progressed, we began to question our use of the term LGBT+. Our decision to use LGBT+ in our research question, and as a key search term, may help to explain why the articles we reviewed did not consider intersections beyond sexuality/gender diversity and dementia. In Westwood (Reference Westwood2020), the use of LGBT+ as an umbrella term was in fact found to obscure more nuanced discussions about other kinds of intersectionality, including the diversity that exists within the LGBT+ community. Like Westwood (Reference Westwood2020: 1), this review questions the usefulness of the LGBT+ umbrella term to capture ‘internal diversity’, despite its political and identity power. Including HIV-Associated Dementia as a search term may also have allowed us to capture papers with a greater intersectional focus.

This limitation has inspired us to advocate for future research that better captures the diversity among those who identify as LGBT+ whose lives are directly impacted by dementia. Researchers could also embrace a wider variety of theoretical frameworks, such as queer theory (King, Reference King, Westwood and Price2016), which was not explicitly used to guide the design of any of the studies in our scoping review. Exploring diverse theories may provide new understandings on the lived experience of LGBT+ people with dementia and their partners. In addition, we argue that there is significant scope to frame dementia differently. Rather than imposing a deficit-focused lens that emphasises what people lose through dementia (Shakespeare et al., Reference Shakespeare, Zeilig and Mittler2019), scholars might view dementia studies as an opportunity to improve, enhance and rally for the supports that LGBT+ people need. In turn, to understand what these supports might look like, scholars will need to engage gender and sexuality diverse people with dementia themselves, specifically through innovative research methods that do not require participants to tell their story in words alone. This research should be based on strong collaborations with LGBT+ organisations who support people with dementia and/or their care partners, to inform the way forward.

Author contribution

LS led the conceptualisation, design and writing of this review. LS developed partnerships and collaborations to make create meaningful questions. LS guided each step of the review, including reading and analysing the short-listed papers. LS drafted and edited substantial sections of the review. IC conducted the literature search, narrowing down the papers to the shortlist. IC analysed the literature and drafted and edited substantive sections of the review. KFG, RW, LP, CEN and FD provided substantial contribution to interpretation of data and critical revision of the intellectual content.

Financial support

This work was supported by the University of Wollongong Global Challenges Keystone Project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.