Article contents

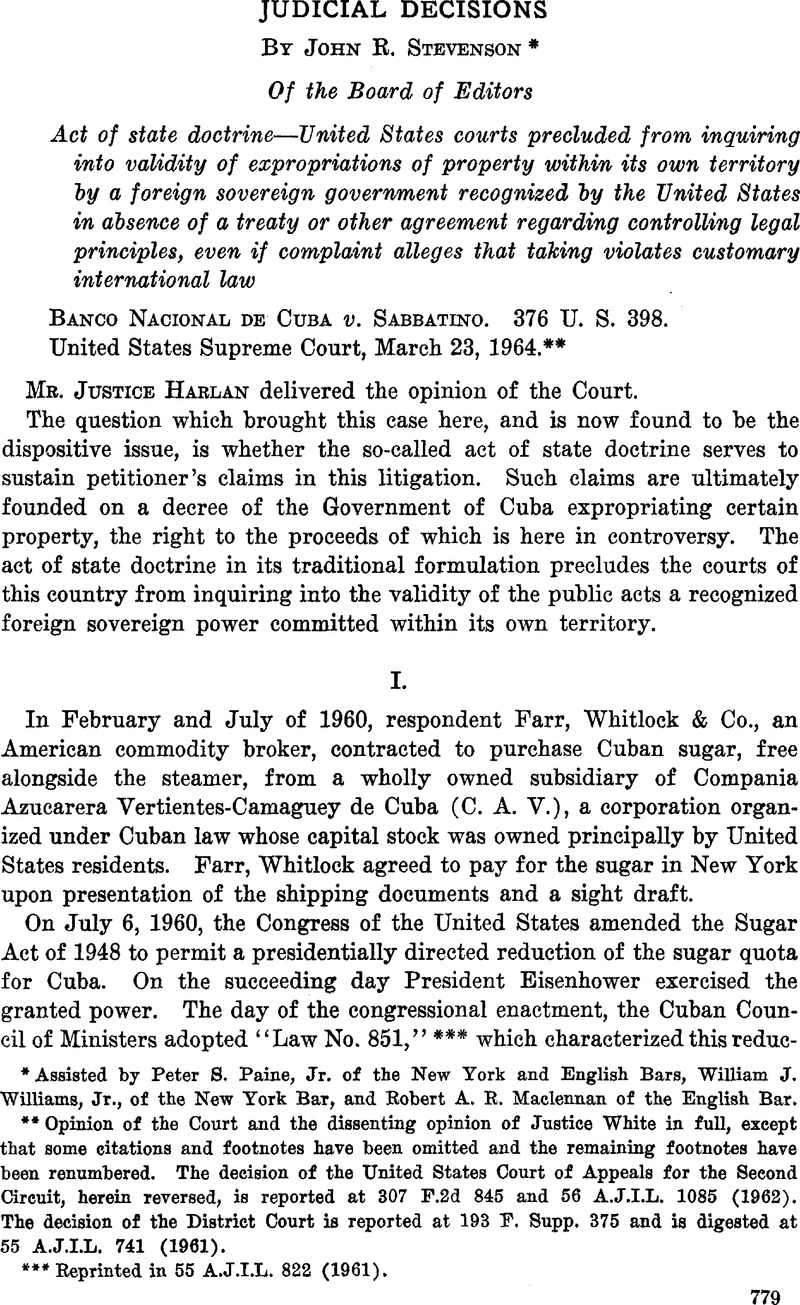

Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Sabbatino. 376 U. S. 398

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial Decisions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1964 by The American Society of International Law

References

1 The parties have treated the interest of the wholly owned subsidiary as if it were identical with that of C. A. V.; hence no distinction between the two companies will be drawn in the remainder of this opinion.

2 The doctrine that nonrecognition precludes suit by the foreign government in every circumstance has been the subject of discussion and criticism… . In this litigation we need intimate no view on the possibility of access by an unrecognized government to United States courts, except to point out that even the most inhospitable attitude on the matter does not dictate denial of standing here.

3 Respondents suggest that suit may be brought, if at all, only by an authorized agent of the Cuban Government. Decisions establishing that privilege based on sovereign prerogatives may be evoked only by such agents … are not apposite to cases in which a state merely sues in our Courts without claiming any right uniquely appertaining to sovereigns.

4 The courts below properly declined to determine if issuance of the expropriation decree complied with the formal requisites of Cuban law. In dictum in Hudson v. Guestier, 4 Cranch 293, 294, Chief Justice Marshall declared that one nation must recognize the act of the sovereign power of another, so long as it has jurisdiction under international law, even if it is improper according to the internal law of the latter state. This principle has been followed in a number of cases… . An inquiry by United States courts into the validity of an act of an official of a foreign state under the law of that state would not only be exceedingly difficult but, if wrongly made, would be likely to be highly offensive to the state in question. Of course, such review can take place between States in our federal system, but in that instance there is similarity of legal structure and an impartial arbiter, this Court, applying the full faith and credit provision of the Federal Constitution. Another ground supports the resolution of this problem in the courts below. Were any test to be applied it would have to be what effect the decree would have if challenged in Cuba. If no institution of legal authority would refuse to effectuate the decree, its “formal” status—here its argued invalidity if not properly published in the Official Gazette in Cuba—is irrelevant. It has not been seriously contended that the judicial institutions of Cuba would declare the decree invalid.

5 The letter stated: “ 1 . This government has consistently opposed the forcible acts of dispossession of a discriminatory and confiscatory nature practiced by the Germans on the countries or peoples subject to their controls. ‘ ‘ 3. The policy of the Executive, with respect to claims asserted in the United States for the restitution of identifiable property (or compensation in lieu thereof) lost through force, coercion, or duress as a result of Nazi persecution in Germany, is to relieve American courts from any restraint upon the exercise of their jurisdiction to pass upon the validity of the acts of Nazi officials.” State Department Press Eelease, April 27, 1949, 20 Dept. State Bull. 592.

6 Abram Chayes, the Legal Adviser to the State Department, wrote on October 18, 1961, in answer to an inquiry regarding the position of the Department by Mr. John Laylin, attorney for amid: “ The Department of State has not, in the Bahia de Nipe case or elsewhere, done anything inconsistent with the position taken on the Cuban nationalizations by Secretary Herter. Whether or not these nationalizations will in the future be given effect in the United States is, of course, for the courts to determine. Since the Sabbatino case and other similar cases are at present before the courts, any comments on this question by the Department of State would be out of place at this time. As you yourself point out, statements by the executive branch are highly susceptible of misconstruction.'’ A letter dated November 14, 1961, from George Ball, Under Secretary for Economic Affairs, responded to a similar inquiry by the same attorney: ‘ ‘ I have carefully considered your letter and have discussed it with the Legal Adviser. Our conclusion, in which the Secretary concurs, is that the Department should not comment on matters pending before the courts.“

7 At least this is true when the Court limits the scope of judicial inquiry. We need not now consider whether a state court might, in certain circumstances, adhere to a more restrictive view concerning the scope of examination of foreign acts than that required by this Court.

8 The Doctrine of Erie Eailroad v. Tompkins Applied to International Law, 33 Am. J. I n t ‘ l L. 740 (1939).

9 Various constitutional and statutory provisions indirectly support this determination, see U. S. Const., Art. I, §8, els. 3, 10; Art. II, §§2, 3; Art. I l l , §2; 28 TJ. S. C. §§1251 (a)(2), (b)(1), (b)(3), 1332 (a)(2), 1333, 1350-1351, by reflecting a concern for uniformity in this country's dealings with foreign nations and indicating a desire to give matters of international significance to the jurisdiction of federal institutions… .

10 … We do not, of course, mean to say that there is no international standard in this area; we conclude only that the matter is not meet for adjudication by domestic tribunals.

11 There are, of course, areas of international law in which consensus as to standards is greater and which do not represent a battleground for conflicting ideologies. This decision in no way intimates that the courts of this country are broadly foreclosed from considering questions of international law.

12 It is, of course, true that such determinations might influence others not to bring expropriated property into the country … so their indirect impact might extend beyond the actual invalidations of title.

13 Of course, to assist respondents in this suit such a determination would have to include a decision that for the purpose of judging this expropriation under international law C. A. V. is not to be regarded as Cuban and an acceptance of the principle that international law provides other remedies for breaches of international standards of expropriation than suits for damages before international tribunals… .

14 This possibility is consistent with the view that the deterrent effect of court invalidations would not ordinarily be great. If the expropriating country could find other buyers for its products at roughly the same price, the deterrent effect might be minimal although patterns of trade would be significantly changed.

15 Were respondents’ position adopted, the courts might be engaged in the difficult tasks of ascertaining the origin of fungible goods, of considering the effect of improvements made in a third country on expropriated raw materials, and of determining the title to commodities subsequently grown on expropriated land or produced with expropriated machinery. By discouraging import to this country by traders certain or apprehensive of nonrecognition of ownership, judicial findings of invalidity of title might limit competition among sellers; did the excluded goods constitute a significant portion of the market, prices for United States purchasers might rise with a consequent economic burden on United States consumers. Balancing the undesirability of such a result against the likelihood of furthering other national concerns is plainly a function best left in the hands of the political branches.

- 1

- Cited by