Article contents

Sei Fujii v. State of California

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial Decisions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1952

References

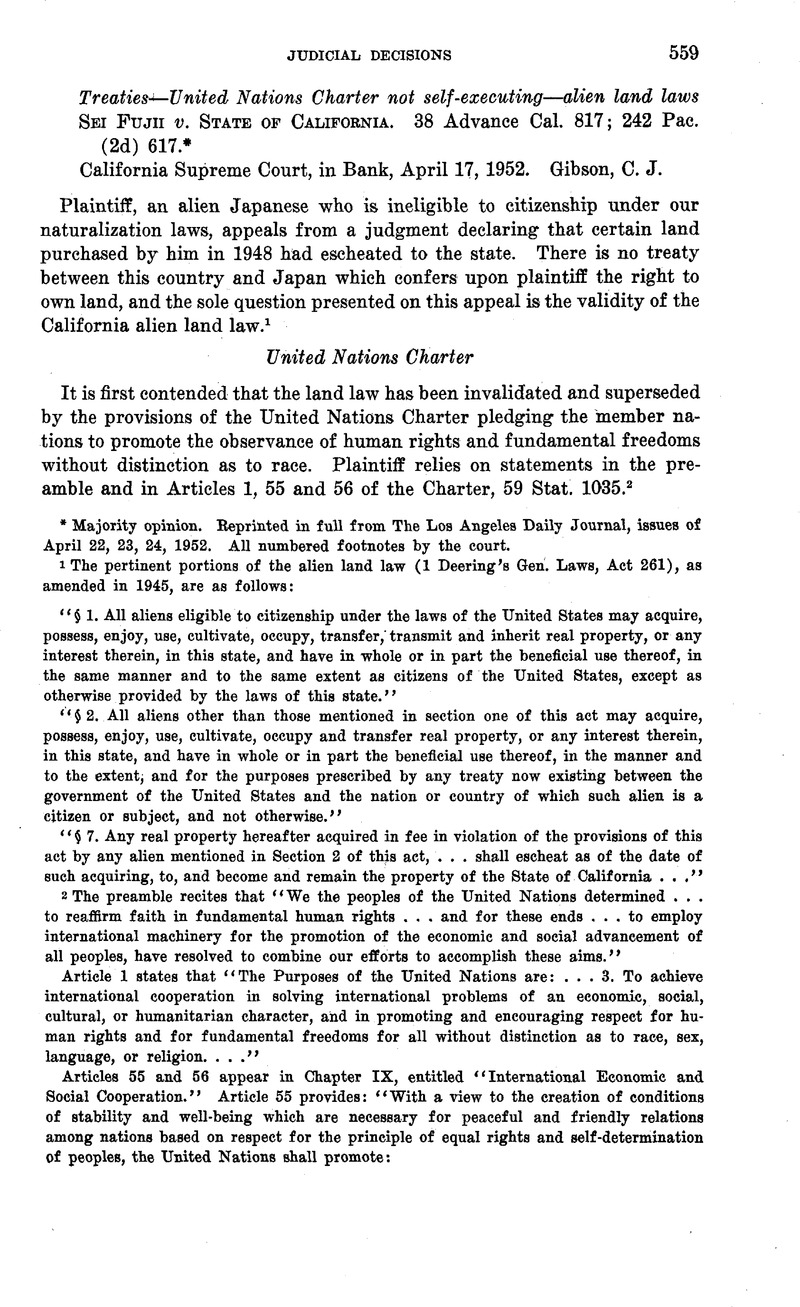

* Majority opinion. Reprinted in full from The Los Angeles Daily Journal, issues of April 22, 23, 24, 1952. All numbered footnotes by the court.

1 The pertinent portions of the alien land law (1 Deering’s Gen. Laws, Act 261), as amended in 1945, are as follows:

“§ 1. All aliens eligible to citizenship under the laws of the United States may acquire, possess, enjoy, use, cultivate, occupy, transfer, transmit and inherit real property, or any interest therein, in this state, and have in whole or in part the beneficial use thereof, in the same manner and to the same extent as citizens of the United States, except as otherwise provided by the laws of this state.”

“§2. All aliens other than those mentioned in section one of this act may acquire, possess, enjoy, use, cultivate, occupy and transfer real property, or any interest therein, in this state, and have in whole or in part the beneficial use thereof, in the manner and to the extent, and for the purposes prescribed by any treaty now existing between the government of the United States and the nation or country of which such alien is a citizen or subject, and not otherwise.”

“§ 7. Any real property hereafter acquired in fee in violation of the provisions of this act by any alien mentioned in Section 2 of thjs act, … shall escheat as of the date of such acquiring, to, and become and remain the property of the State of California …”

2 The preamble recites that “We the peoples of the United Nations determined … to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights … and for these ends … to employ international machinery for the promotion of the economic and social advancement of all peoples, have resolved to combine our efforts to accomplish these aims.”

Article 1 states that “The Purposes of the United Nations are: … 3. To achieve international cooperation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.…”

Articles 55 and 56 appear in Chapter IX, entitled “International Economic and Social Cooperation.” Article 55 provides: “With a view to the creation of conditions of stability and well-being which are necessary for peaceful and friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, the United Nations shall promote:

a. higher standards of living, full employment, and conditions of economic and social progress and development;

b. solutions of international economic, social, health, and related problems; and international cultural and educational cooperation; and

c. universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion.”

Article 56 provides: “All Members pledge themselves to take joint and separate action in cooperation with the Organization for the achievement of the purposes set forth in Article 55.”

3 In Foster v. Neilson, certain treaty provisions were held not to be self-executing on the basis of construction of the English version of the document. Subsequently upon consideration of the Spanish version, the provisions in question were held to be self-executing. (United States v. Percheman, 7 Pet. 51.) Chief Justice Marshall’s language in the Foster case, however, has been quoted with approval in later cases. (United States v. Rauscher, 119 U. S. 407, 417–418, 7 S. Ct. 234, 239–240; Valentine v. United States, 299 U. S. 5, 10, 57 S. Ct. 100, 103.)

4 It should be noted, however, that the treaty involved in the Bacardi case also contained a specific provision, not discussed by the court, that its terms “shall have the force of law in those States in which international treaties possess that character, as soon as they are ratified by their constitutional organs.” (311 U. S. 150, 159, 61 S. Ct. 219, 224.)

5 See, for example, Porterfield v. Webb [1924], 195 Cal. 71; Mott v. Cline [1927], 200 Cal. 434; Dudley v. Lowell [1927], 201 Cal. 376; People v. Osaki [1930], 209 Cal. 169; People v. Morrison [1932], 125 Cal. App. 282 [hearing denied]; Alfafara v. Fross [1945], 26 Cal. 2d 358; People v. Oyama [1946], 29 Cal. 2d 164; cf. Takahashi v. Fish & Game Com. [1947], 30 Cal. 2d 719 [involving legislation prohibiting issuance of commercial fishing licenses to aliens ineligible to citizenship].

6 This section provides for a prima facie presumption of intent to evade escheat upon proof that the consideration for a conveyance of realty was paid or agreed to be paid by an ineligible alien and that title was taken in the name of a citizen or eligible alien.

7 For all practical purposes, immigration of ineligible aliens was halted by the Exclusion Act of 1924. (8 U. S. C. A. § 213c.)

8 Compare legislative devices to deprive Negroes of franchise without express mention of race. See Guinn v. U. S., 238 U. S. 347, 35 S. Ct. 926; Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 59 S. Ct. 872; Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, 64 S. Ct. 757.

9 See McGovney, Anti-Japanese Land Laws [1947], 35 Cal. L. Rev. 7, 18–20, 39–41.

At early common law an alien could acquire real property by gift, purchase or devise, but his rights in the property were subject to forfeiture by the crown. The historical basis for this disability has been traced to fear that the safety of the English crown was threatened by the large number of Normans and Frenchmen owning English land in the thirteenth century. (See Pollack and Maitland, History of English Law [2d ed., 1898] 463; 9 Holdsworth, History of English Law [1926] 92–93.) Early commentators offered such explanations for the rule as the fact that aliens, owing a foreign allegiance, were regarded as incapable of performing military service for the king, one of the most important incidents of the feudal tenure system. (See 2 Blackstone Comm. 250; State v. B.C. & M. R.R. Co., 25 Vt. 433, 438.) Further, in time of war aliens “might fortify themselves in the heart of the realm” and, in time of peace, so much of the freehold land might be held by aliens that there would not be enough English freeholders to man the juries and hence “there should follow a failure of justice.” (Calvin’s Case [1609] 77 Eng. Rep. 377.) France and England abolished discrimination against aliens with regard to property rights in 1819 and 1870, respectively.

10 When the alien land law was enacted a treaty permitted alien Japanese to lease commercial and residential property. This treaty was subsequently abrogated, but the statute was construed as having incorporated the treaty provisions and as permitting such leases. (Palermo v. Stockton Theatres, Inc., 32 Cal. 2d 53.)

* Carter, J., also concurred in the result, but wrote a separate opinion not discussing the treaty point. Schauer, Shenk and Spence, J.J., dissented on the constitutional question in an opinion by the first, in which it was stated: “I agree that the United Nations Charter, as presently constituted and accepted was not intended to, and does not, supersede existing domestic legislation of the United States or of the several states and territories.” The three dissenting judges thought that the California court should follow the United States Supreme Court decisions upholding constitutionality of the statute until that Court had reversed itself on the point.

- 2

- Cited by