Rebel groups often provide governance as a means of contesting formal state power (Arjona, Kasfir, and Mampilly Reference Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015), but criminal groups with narrower aims also govern people and spaces. Criminal governance can extend beyond organizations’ core members to entire illicit markets and the civilian communities where such markets operate. Canonically associated with mafias and protection rackets (e.g., Blok Reference Blok1974; Skaperdas and Syropoulos Reference Skaperdas, Syropoulos, Fiorentini and Peltzman1997; Tilly Reference Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985), criminal governance is increasingly being provided by drug-trafficking organizations (DTOs), quite often ones based within prison. Scholarship on US prison gangs has provided foundational insights (Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011), but generally lacks systematic data on the practices that sustain and constitute prison-based criminal governance, especially beyond the prison walls. Moreover, US cases do not cover the empirical range of prison-based governance: Brazilian prison gangs govern more intensely and extensively, ruling large urban populations and across enormous swaths of territory. This article explores the governance practices of São Paulo’s Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), likely the most powerful prison gang in the world and the leading case of prison-based criminal governance. We analyze a trove of the PCC’s own financial and disciplinary records, identifying a novel form of criminal governance and theorizing its underlying mechanisms.

Founded within a São Paulo prison in 1993 by a handful of inmates, the PCC has grown into Brazil’s foremost threat to state authority. With some 29,000 “baptized” members as of 2018 (Paes Manso and Dias Reference Paes Manso and Dias2018, 19), it is among the largest criminal organizations in the hemisphere. The PCC now controls over 135 prisons in São Paulo state alone and has established cells in all 27 Brazilian states and at least five neighboring countries. It leverages this control to project its power onto the streets, with countervailing effects. The PCC has repeatedly orchestrated debilitating terror attacks on state and civilian targets. Yet it also banned unauthorized killings throughout the informally urbanized peripheries where it wields influence, contributing to a drastic and sustained reduction in statewide homicide rates of about 75 percent.

We analyze systematic data on the PCC’s street-level drug business and internal disciplinary system, making empirical and theoretical contributions. Empirically, we find that drug retailing is consignment-based, punishments are mild and meticulously recorded, default rates are low, and the resulting profits fund welfare for member families. These features, we hypothesize, flow jointly from the PCC’s overarching approach to governance: not just imposing its rule, but establishing a form of legitimacy along Weberian, rational-bureaucratic lines. This approach induces voluntary compliance among members while minimizing internal violence, keeping a decentralized, credit-based drug business profitable in spite of endemic agency problems, and in the face of intense militarized policing.

The descriptive findings in this trove are varied. For example, the same organization that loans guns and rent money to recently released members getting a fresh start also spent USD 500 on children’s Easter eggs. We highlight four sets of substantively and theoretically puzzling findings.

First, the PCC’s trafficking operations in upstate São Paulo—the region covered by our data—run on a consignment basis. This contrasts with the hierarchical franchise structure and territorial control employed by Rio de Janeiro’s Comando Vermelho—an older prison-gang-cum-drug-cartel that the PCC initially emulated—and the Chicago gang analyzed by Levitt and Venkatesh (Reference Levitt and Venkatesh2000). In the five months that we observe, the PCC consigned 550 kg of crack and 90 kg of powder cocaine to a decentralized, competitive network of some 500 individual dealers across 89 municipalities, extending about USD 3.2 million in microcredit.Footnote 1 The nonpayment rate, we estimate, was lower than the 30.7 percent markup the PCC charges dealers.

Second, the resulting profits are not paid out to an “owner” or “shareholders” but rather used to provide collective goods. After paying off bulk drug purchases, revenues primarily financed an elaborate transportation network for members’ families to far-flung prisons on visitation days and other member welfare benefits, such as funeral costs.

Third, the PCC possesses a complex system of internal discipline characterized by clear rules, collectivist norms, and administrative procedures to ensure transparency and fairness. Critically, unpaid debts were punished exclusively with nonviolent sanctions such as suspension or expulsion from the organization, and physical punishment was exceedingly rare.

Fourth, the documents reveal a thoroughgoing embrace of bureaucracy: codified structures and procedures, reflected in meticulous recordkeeping. While attention to detail is unsurprising in financial documents, even greater care goes into maintaining the individual personnel files we dub “criminal criminal records,” which track members’ background and history of interactions with the organization, including previous infractions. The PCC, our trove reveals, is a prodigious producer and keeper of data.

We advance a theory of legitimate criminal governance to explain these findings. The PCC’s consignment model is subject to agency problems: It requires regular repayment by far-flung dealers with incentives to default. The procedurally fair and meticulously documented system of “criminal criminal justice” solves this problem, inducing widespread voluntary compliance through several complementary mechanisms. At the level of individual rationality, the PCC’s procedures yield accurate records and common knowledge of dealers’ past performance and infractions, so that even a mild punishment like a short suspension (by far the most common punishment observed) carries a powerful stigma, incentivizing timely debt repayment. At a more systemic level, the relative mildness of the PCC’s enforcement regime, its attention to fairness in business dealings (including negotiated solutions for debtors in dire straits), and its prioritization of public-goods and welfare provision all flow from a depersonalized bureaucracy oriented around a body of collectivist norms, rules, and practices. The result is a criminal form of legitimate, rational-bureaucratic authority (Weber Reference Weber1968) characterized by submission and loyalty not to individual charismatic leaders but to a fair, efficacious, and universal “law.”

How do mild punishments like suspension from the organization induce individual compliance? Ultimately, it is by providing information to other criminals. As Gambetta (Reference Gambetta2009) observes, for criminals to work together, they need to identify and reliably assess one another without revealing themselves to authorities. Gambetta focuses on symbolic codes as signals, but suggests that incarceration, ironically, can solve this adverse-selection problem since “just being a prisoner is a clear and simple sign that one is criminally inclined” (Reference Gambetta2009, 11). Moreover, the fairer the official criminal justice system, that is, the more accurately it distinguishes the guilty from the innocent, the more reliable the signal that incarceration sends.

An inverse logic applies to prison gangs’ internal disciplinary systems. A member in good standing, besides having been convicted by the state, carries the gang’s seal of approval; an expelled or punished member has been found wanting. What others can infer from gang punishment depends on that gang’s rules, norms, and disciplinary practices. If sanctions are meted out arbitrarily, they convey little information about punished members’ actual performance or “type.” Conversely, the fairer the “criminal criminal justice” system, the clearer the signal that punishment sends. A mild, nonviolent punishment, if fairly meted out and meticulously recorded, can carry a burdensome stigma.

The PCC’s elaborate, standardized procedures must be understood in this light. Its system of graded punishments for dealers with overdue consignment debts—including an escalating “three strikes” rule—is tempered by flexibility and patience when dealers face unpredictable setbacks (such as arrest) or make good faith efforts to repay. For more serious infractions, the PCC employs lengthy and potentially risky semi-public trials, often adjudicated by imprisoned “elders,” and designed to reduce false convictions and excessive punishment (e.g., Feltran Reference Feltran2010). The costs of operating this system, we argue, are offset by important dividends: The PCC’s reputation for not being hasty, arbitrary, or unfair increases the stigma of suspension or expulsion, because those convicted cannot credibly claim innocence.

The PCC’s meticulous recordkeeping amplifies this effect; who needs symbolic codes when you have detailed records of previous misconduct and punishment, including a cell phone number to call for case details? This use of recordkeeping to induce good behavior recalls several theorized mechanisms in the literature. Shapiro and Siegel (Reference Shapiro and Siegel2012) show how the institutional memory that recordkeeping facilitates allows terrorist leaders to better motivate operatives who may otherwise slack or skim.Footnote 2 Relevant too is Milgrom et al.’s model of the Law Merchant, in which accurate, centralized recordkeeping can produce cooperation “without the benefit of state enforcement of contracts” (Reference Milgrom, North and Weingast1990, 2). Such conditions prevail in the criminal underworld, especially in the far-flung regions covered by our trove, where the PCC’s ability to physically punish rulebreakers may be relatively weak.

However, the PCC also employs elaborate bureaucracy, codified procedures, normative appeals, and generally mild punishment in places where its punitive power is immense: within prison (Dias and Salla Reference Dias and Salla2013) and São Paulo’s urban periphery (e.g., Feltran Reference Feltran2010). Moreover, our data suggest that even when PCC leaders harshen discipline to address excessive non-compliance, they avoid draconian measures that might maximize short-term profits at the expense of fairness. Thus, we argue, the PCC deliberately eschews raw coercive power in order to maintain a form of legitimacy, along rational-bureaucratic lines.

It is an enduring irony that trustworthy, efficient, “Weberian” governance should arise among the targets of a state coercive apparatus guided by a brutal and corrupt “unrule of law” (Mendez, O’Donnell, and Pinheiro Reference Mendez, O’Donnell and Pinheiro1999), in a country long hamstrung by bureaucratic inefficiency and patrimonialism (Evans Reference Evans1995). More ironic still, PCC governance depends on the state’s own mass-incarceration policies, which swell the PCC’s ranks and—by raising the chances of eventual incarceration—give it leverage over criminals on the street (Lessing Reference Lessing2017). In São Paulo, these policies inadvertently, perversely helped create a criminal “pocket of efficiency” (Geddes Reference Geddes1990) capable of governing a sprawling prison system, a decentralized criminal network, and a vast, impoverished urban periphery. While not the first or only Brazilian prison gang to establish street-level governance, the PCC’s rational-bureaucratic structure contrasts with more charismatic, territorial, and violent approaches, constituting a novel and potentially transformative model for organizing crime from behind bars. The PCC’s ongoing expansion throughout the prisons and peripheries of Brazil and into neighboring countries is chilling evidence of this.

In the sections below, we conceptualize criminal governance, provide empirical background, describe our data and related ethical and methodological issues, present empirical findings, and discuss these findings in light of our theory of the PCC’s legitimacy-based approach to governance. We conclude with implications for literatures on state formation and insurgency.

VARIETIES OF CRIMINAL GOVERNANCEFootnote 3

Criminal governance is more varied than rebel governance in terms of who is governed. “Rebel governance” generally refers to rebel–civilian interactions, and criminal organizations may also impose rules on and/or provide public goods to noncriminal “civilian” populations (e.g., Leeds Reference Leeds1996; Ley, Mattiace, and Trejo Reference Ley, Mattiace and Trejo2018). However, “criminal governance” may also refer to groups’ internal governance (e.g., Leeson and Skarbek Reference Leeson and Skarbek2010), or their governance over wider populations of criminal actors, often within a specific illicit economy, ethnicity, or territory (e.g., Campana and Varese Reference Campana and Varese2018; Skarbek Reference Skarbek2011). This capacious understanding of “criminal governance” is worth maintaining, since governance mechanisms and institutions often operate across these levels (Lessing Reference Lessing2018).

Criminal governance also varies in terms of what is governed, and where. Both criminal and rebel governance tend to occur in places where the state is weak. Yet, criminal groups rarely pursue rebels’ overarching goal of “competitive state-building” (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006). Rather than challenging state power directly, criminal governance flourishes in its interstices. These power vacuums can result from state neglect or absence, as in the Sicilian hinterlands where the Mafia arose (Blok Reference Blok1974), but also through state prohibition of economic activities, producing illicit markets (Skaperdas and Syropoulos Reference Skaperdas, Syropoulos, Fiorentini and Peltzman1997). Criminal governance is often narrow, covering some criminal markets and informal economies but not others; when it extends over civilian life, it often does so unevenly. A gang might monopolize drug sales, prohibit property crime, and punish civilian contact with police, but leave realms such as informal transport and electoral politics unregulated. Consequently, the boundary between criminal and formal state governance is routinely jagged, shifting, and even porous (Arias Reference Arias2006).

Another source of variation is the type of organization that governs. Whereas traditional mafias, drug cartels, and street gangs tend to govern the areas and social strata where they are physically based (Campana and Varese Reference Campana and Varese2018; Levitt and Venkatesh Reference Levitt and Venkatesh2000), prison gangs have demonstrated a capacity to govern from a distance. This allows them to organize retail drug markets throughout cities and even states, something street gangs and mafias have rarely if ever accomplished (e.g., Hagedorn Reference Hagedorn1994). The ethnic, racial, and cultural bases of group membership are also important. US prison gangs are sharply divided by race and ethnicity, and generally only govern co-ethnic street gangs, limiting their geographic and demographic reach. In Brazil, a myth of “racial democracy” obscures both the racialized conditions of urban poverty, violent policing, and mass incarceration that foster prison gangs (Alves Reference Alves2015), and, ironically, produces racially integrated gangs capable of city- or statewide hegemony.

A critical dimension of variation, we argue, concerns the “how” of criminal governance. Conventional wisdom portrays criminal governance as highly coercive, personalistic, and arbitrary. Dons, capos, and gang bosses are often charismatic authority figures, cultivating fearful reputations, and deploying violence strategically to assert dominance and reward loyalty. The PCC, we argue, has developed a style of criminal governance closer to Weber’s (Reference Weber1968) notion of rational-bureaucratic legitimacy.

One of our contributions is to broaden the observed empirical range of these dimensions. We analyze a rare body of systematic data on the administrative and disciplinary practices that support the PCC’s prison-based governance over a vast street-level network of sworn members and autonomous affiliates and the retail drug markets they operate in. Additional sources suggest that it adopts similar governance practices both within prison and over noncriminal civilian populations. That makes PCC governance, relative to US cases, more universal, covering diverse populations across large urban peripheries; more extensive, covering all of São Paulo state and expanding rapidly throughout Brazil; and, we suspect, less violent.

THE PCC

The PCC is the largest and most sophisticated of Brazil’s facções criminosas, or “criminal factions”—gangs born and based in prison that come to control “slum” territories and illicit markets beyond prison. The PCC initially modeled itself on the Comando Vermelho (CV) faction, which formed in the prisons of Brazil’s military dictatorship in the 1970s and dominated Rio de Janeiro’s favelas in the 1980s. The CV then fractured, fighting brutally against rivals and police ever since. In contrast, the PCC maintains hegemony over São Paulo’s prison system since the 1990s and its urban periphery since the 2000s. It also developed into a more complex organization than the CV, with distinctive governance practices and a deliberate policy of expansion beyond São Paulo to other Brazilian states and even neighboring countries. Since 2000, the rest of Brazil has become increasingly “factionalized,” with local “copycat” factions emerging in the wake of the PCC’s (and to a lesser extent, the CV’s) arrival.

Recalling social movements in some ways, Brazil’s factions often frame their organizing purpose as a “struggle” (luta) against violence and abuse, particularly by the state. This intermingling of normative and criminal goals began with the CV. Its founders entered prison as common criminals, but gleaned collectivist techniques from Cold War leftists they were unwisely housed with by the military dictatorship. Whereas the middle-class, predominantly white leftists eventually won amnesty by distinguishing themselves from common criminals, one CV founder explains, “Our path could only be the opposite: integration with the prison masses and the fight for liberty using our own resources” (Lima Reference Lima1991, 43).Footnote 4

The PCC’s founding was also catalyzed by state repression: the 1992 Carandiru prison massacre, in which São Paulo Military Police killed 111 mostly defenseless prisoners who had rioted to protest guard abuse. A group of survivors, transferred to a harsh maximum-security prison under Carandiru’s former warden, formed the PCC in 1993. Its founding statute states: “We must remain united and organized to avoid a similar or worse massacre than [Carandiru], a massacre that will never be forgotten in the conscience of Brazilian society… because we, the Comando, will change current carceral practices, inhumane, full of injustice, oppression, torture, and massacres.” The statute declared an alliance with the CV and adopted its motto “Peace, Justice, and Liberty.” The statute has been updated several times and further distilled into a guiding mission: “Peace among thieves and war against the state” (Biondi Reference Biondi2016).

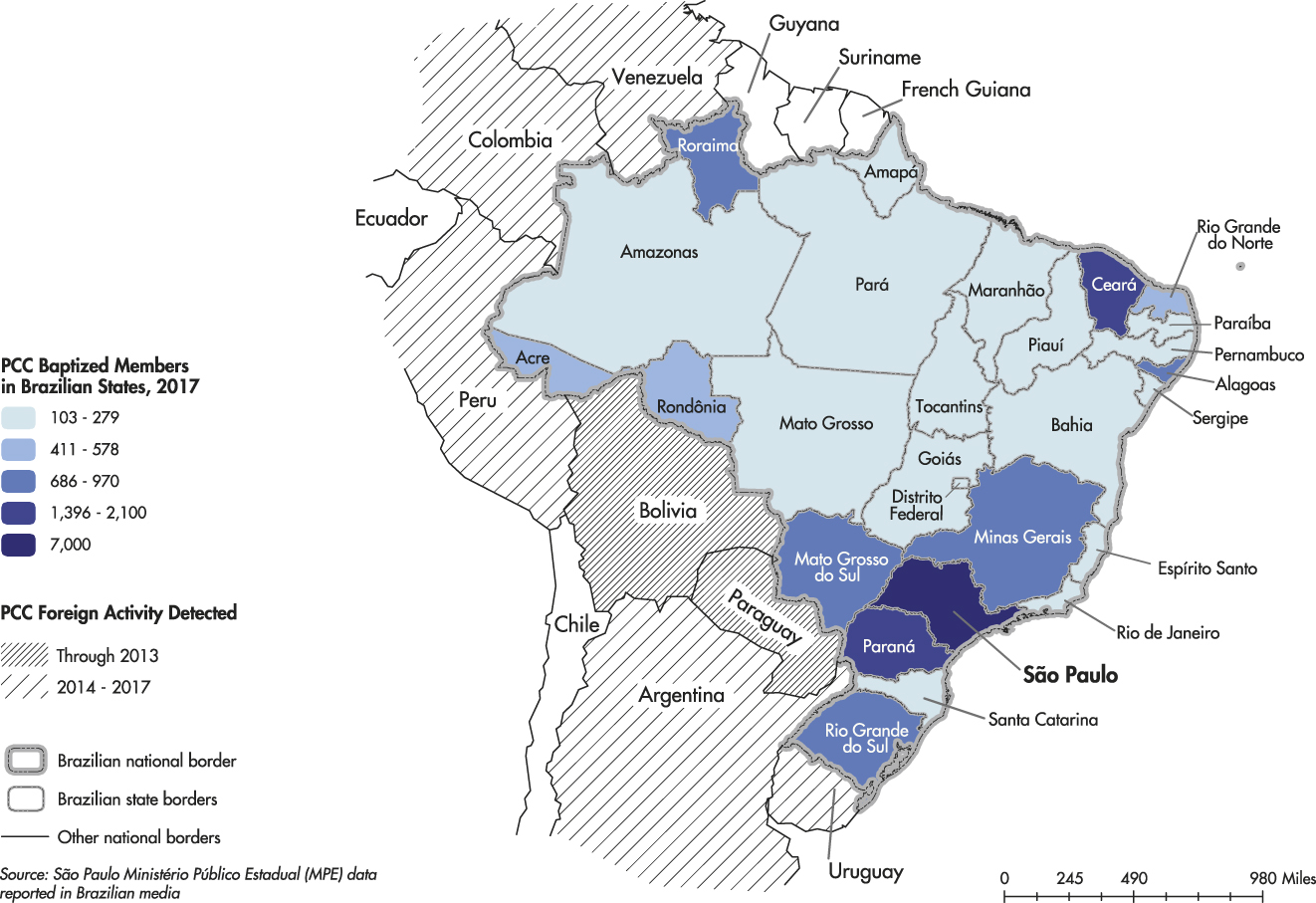

As the CV did in Rio, the PCC violently eliminated its rivals in São Paulo’s prisons, imposing a governance regime that won the allegiance of inmates. It prohibits theft, rape, crack cocaine use, and unauthorized violence; provides limited welfare (food, medicine, and hygiene products) for the poorest inmates; ensures the supply of drugs, cell phones, and other contraband; effectively administers daily prison life; and bargains collectively for improvements in prison conditions, especially around family and conjugal visits. A disastrous official policy of transferring PCC leaders to other prisons (in hopes of neutralizing them) helped them dominate São Paulo’s prison system and establish cells throughout Brazil (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Geography of PCC Expansion in South America

A 2002 internal coup led to a “democratizing” reform, symbolized by the addition of “Equality” to the “Peace, Liberty, and Justice” motto (Biondi Reference Biondi2016, 60). The new leader, alias “Marcola,” replaced the PCC’s personalistic, “pyramidal” structure with a flattened hierarchy of institutionalized posts called responsas (“responsibilities”), through which members rotate. Marcola deliberately minimized his own leadership role, and extended the PCC’s practice of open discussion to every level of decision-making, supported by norms against pulling rank (igualdade and humildade). In sworn testimony, one deposed PCC founder highlighted the radical nature of Marcola’s reform: “In our time there was no such circulating system of authority. We were the founders. We had the last word and everyone else… obeyed and did exactly what we ordered. There was nothing about consulting two, three, four, or twenty opinions” (in Marques Reference Marques2010, 325).

In the wake of the 2002 coup, and as the PCC established hegemony within prison, it moved away from brutal executions of rivals and noncompliers, adopting a system of gradated, mostly nonviolent punishments (Dias and Salla Reference Dias and Salla2013) similar to the one outside prison we document. It also institutionalized formal tribunals (debates) for serious violations in which juries of imprisoned leaders hear testimony from witnesses, victims, and even “counsel” (Biondi Reference Biondi2016; King and Valensia Reference King and Valensia2014), all anchored in a rich normative vocabulary emphasizing individual moral uprightness (proceder) and a collective “ethos of crime” (Marques Reference Marques2010).

From 2000 on, the PCC extended both its criminal activity and governance practices from prison to the urban periphery of São Paulo and beyond. Whereas the CV took militarized control over Rio’s peripheral communities, granting its semi-autonomous bosses local monopolies on drug sales (Grillo Reference Grillo2013), the PCC established its authority without hard territorial control, regulating criminal activity and supplying drugs to a wide network of members and affiliates.

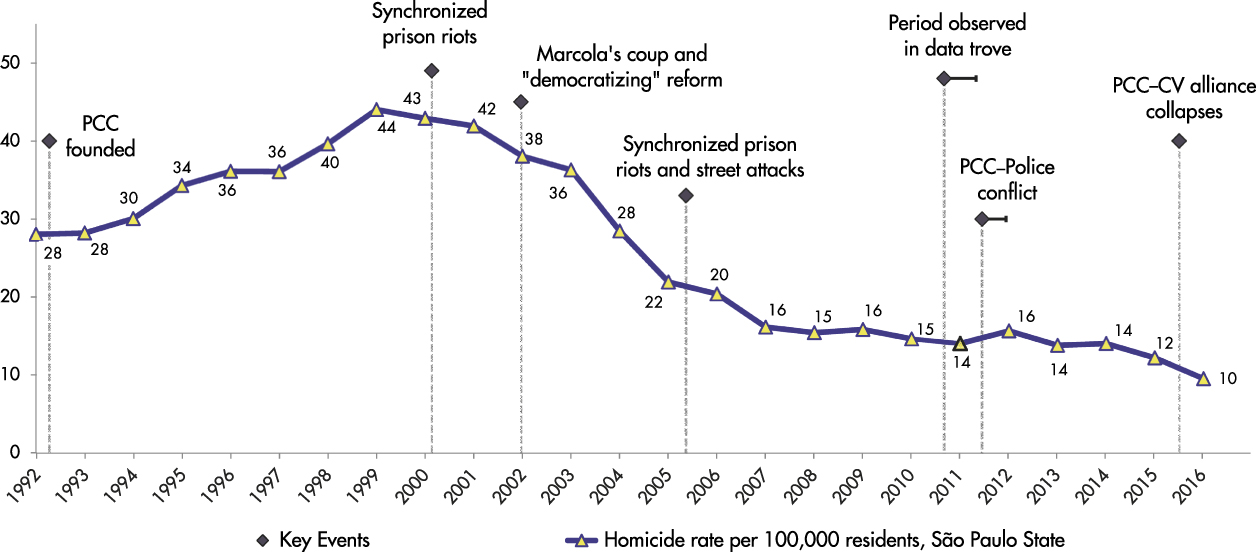

The PCC claimed a monopoly not on drug retailing but on the legitimate use of force, banning killings except those sanctioned by its prison-based tribunals (Feltran Reference Feltran2018). Ethnographies of low-income neighborhoods in the early 2000s document the imposition of this “criminal code of conduct” (lei do crime)—sometimes violently resisted by incumbent criminal groups but often peacefully acceded to—and the subsequent drop in killings that were “no longer allowed” (e.g., Alves Reference Alves2015; Feltran Reference Feltran2010; Hirata Reference Hirata2010). Biderman et al.’s (Reference Biderman, M.P. De Mello, S. De Lima and Schneider2018) difference-in-differences analysis confirms that PCC arrival in neighborhoods caused local reductions in homicides, contributing significantly to São Paulo’s massive crime drop since 2001 (Figure 2). The PCC’s tribunal system is now used throughout São Paulo’s periphery, including by noncriminals for everyday dispute resolution. It has a high bar for conviction and deters false accusations by sanctioning unsuccessful plaintiffs (Biondi Reference Biondi2016; Feltran Reference Feltran2010).

FIGURE 2. Timeline of the PCC

In 2006, the PCC used its power on the streets to launch a synchronized wave of attacks on São Paulo’s urban transportation, police, and banking infrastructure, while instigating simultaneous riots in over 90 prisons. The attacks brought São Paulo to a standstill for four days, ending only after officials met face-to-face with Marcola. Since 2006, São Paulo has seen relative calm, suggesting unspoken accords between authorities and the PCC; a brief outbreak of PCC–state conflict in 2012 was likely the result of a renegotiation of this tenuous “consensus” (Denyer Willis Reference Denyer Willis2015). Meanwhile, the PCC’s early, haphazard spread gave way to a deliberate strategy of expansion to every corner of Brazil and even neighboring countries (Figure 1). This colonizing project has brought it into conflict with CV-allied local factions, contributing to the 2016 collapse of the PCC-CV alliance and the subsequent outbreak of street-level turf wars and prison massacres throughout Brazil, leaving hundreds dead (Paes Manso and Dias Reference Paes Manso and Dias2018).

DATA

A trove of internal PCC documents, our primary source, was given unsolicited to Denyer Willis by a São Paulo state bureaucrat involved in investigations of the PCC, during ethnographic research. We describe these data, address ethical and methodological concerns, and discuss the additional sources we use to increase reliability and provide context.

The document trove consists of computer files and scans of a handwritten notebook seized by police during the 2012 arrests of two PCC members who held the posts of bookkeeper (livro) and disciplinarian (disciplina). Almost all the documents relate to and were created by the administrative unit known as the “Interior,” covering most of São Paulo state outside Greater São Paulo city, and its seven regional subdivisions (Regionais). The documents refer overwhelmingly to the period September 2011–October 2012.

The trove contains over 500 files, including duplicates and dozens of .mp3 music files apparently intended to deceive investigators if seized. We focus on a subset of unique documents:

• 23 ledgers (fechamentos, literally “closings”) (19 weekly, 1 bi-weekly, and three monthly).

• 15 “X-Ray” documents (raio X) detailing individual drug consignments to members and affiliates.

• 5 “bad-debt reports” (relatórios) listing debts thought to be uncollectable because of individuals’ expulsion, disappearance, imprisonment, or death.

• 66 scanned pages from the disciplinarian’s handwritten notebook (henceforth “DHN”), mostly detailing individual punishments.

• A set of 98 Word files, each recording an individual punishment, seized together with DHN (henceforth “DWF”).

• 10 assorted Word and Excel documents, including intra-organizational communiqués (salves).

Such data raise important ethical and methodological concerns. Critical to both, our trove is almost certainly part of a larger cache of internal PCC documents amassed by the São Paulo Office of the Public Prosecutor (Ministério Público do Estado, MPE) during a major investigation that produced over 150 indictments—though few convictions—in 2013. We sought, unsuccessfully, to obtain the complete MPE cache. However, detailed accounts of these documents and the MPE’s analysis of them appear in the State Record of Judicial Proceedings (Diário Oficial de Justícia de São Paulo, DJSP); sample documents and summary findings were also published by journalists who were given partial access (e.g., Barbieri Reference Barbieri2014; Godoy and Paes Manso Reference Godoy and Paes Manso2014). These sources’ descriptions of the documents’ formatting and structure match those in our trove. Moreover, it is unlikely that state officials possessed our trove yet withheld it from the MPE. Hence, our supposition that the MPE’s cache includes our trove, and our confidence that our documents are genuine.

Our data contain personally identifiable information (PII) about individuals’ criminal association and drug trafficking; none of these individuals gave informed consent, raising serious ethical concerns. We obtained waivers of consent from our respective IRB boardsFootnote 5 based on our anonymization of results; our data security regime; and the low risk of additional harm to subjects and families from inadvertent leaks, since the data were previously vetted by state prosecutors.

The data also raise questions of reliability and bias. How do we know these documents are genuine and that they provide a representative picture of the PCC? We follow Mafia scholars’ advice both to seek external validation using “all available contextual evidence”—including official files and interviews with key informants—and to carry out “internal validity control” by checking consistency across our documents and analyzing their metadata (Campana Reference Campana2016, 5).

Both external and internal evidence suggests our trove was not forged. The MPE’s description (DJSP 2015) of its cache of documents closely resembles ours, including the “smokescreen” .mp3 files. Our trove’s internal consistency also makes a forgery by officials implausible; for example, the ledgers’ closing dates match their respective “last-modified” dates in the file metadata. The PCC could have fabricated or falsified the data to mislead officials, but then why would it include so much evidence of criminal activity, linked to hundreds of individual names? That the documents were seized in raids along with drugs and weapons casts further doubt on this possibility. As an additional check, we located media reports and official records validating numerous individual arrests and the single execution recorded in our data.

A key concern for reliability is the incompleteness of our data on two fronts. First, as is often true of seized internal documents (Gutiérrez Sanín Reference Gutiérrez Sanín2008), the trove is a nonrandom sample; it covers less than a year in the life of one PCC administrative subunit, limiting our view geographically (only part of São Paulo state), structurally (only the street-level drug business, from the interior level downward), and temporally. This could lead to bias if the region, administrative practice, and/or period we observe are exceptional. We draw on secondary evidence suggesting that operations elsewhere are broadly similar. However, the PCC is a large and evolving organization. Without additional systematic data, we cannot be sure our findings apply beyond the time and places observed.

Second, some documents are clearly missing: at least one monthly ledger and several “X-Ray” documents. These gaps seem minor—there is enough redundancy across documents to fill in most missing information, or make educated guesses. However, we cannot be sure that an entire document type is missing. The most relevant possibility is that violent punishments were carried out but not documented together with the nonviolent punishments recorded by the disciplinarian. If true, our claim that the PCC relies almost exclusively on nonviolent punishment would be biased. However, the recording of a single execution—as well as many nonviolent punishments—in the bad-debt reports suggests that, had other executions occurred, we would have some record of them.

The trove’s incompleteness, and any resulting bias, is unlikely to be due to deliberate withholding of documents. First, Denyer Willis watched the bureaucrat copying the trove, and saw no effort to selectively include or exclude material. Second, following Robertson (Reference Robertson2007, 790–91), we can consider the likely motives of the officials who provided sensitive data. Similar data were provided to Brazilian media around this time; the resulting articles emphasized the PCC’s size and brazenness, suggesting that if officials leaked selectively, they did so to foster a fearful image of the gang. Yet, our trove lacks data on the PCC’s core drug markets (Greater São Paulo), and points to less sensational qualities than officials hypothetically sought to convey. Our informant might have sought to counteract prior leaks, but handing a carefully curated data trove to a then-graduate student seems like a suboptimal way to do so. In any case, the caveats above apply to any bias, whether accidental or deliberate.

A final reliability concern involves interpretation. Formatting, orthography, and accounting conventions are extremely erratic; nicknames, abbreviations, slang, and code words are ubiquitous and inconsistent. While both authors are fluent in Portuguese and familiar with gang tropes, the nature of the data called for thoughtful approaches to analysis and, at times, careful conjecture.

To “stay true” to the data, we conducted our analysis before turning to additional sources for triangulation and context. The MPE’s analysis and secondary sources largely corroborate our assessment of the PCC’s structure and interpretation of key terms. Two additional data sources come from the authors’ field research. The first is a smaller trove of seized PCC documents (henceforth S2) obtained by Denyer Willis via a different state source. Unlike our primary trove, S2 covers Greater São Paulo, but thinly; it covers a wider variety of PCC administrative subunits, including prison administration, but does not contain punishment records. Because of S2’s variegated but limited nature, we do not systematically analyze it. Rather, it corroborates some findings, and provides context about the PCC’s larger structure and division of labor. Second, we draw on Lessing’s ongoing study of the PCC’s expansion throughout Brazil, including interviews with incarcerated PCC members, state officials, and favela residents.Footnote 6 This study excludes São Paulo state to focus on PCC expansion, so it cannot directly corroborate our data. However, it includes places like Paraná state that resemble São Paulo’s Interior in terms of PCC penetration and distance from São Paulo city.

FINDINGS

Organizational Structure

The PCC has a sophisticated bureaucratic structure, made up of executive and managing committees (sintonias, literally “getting in tune”) for different functions, replicated across multiple administrative levels. Our data directly confirm the existence of at least three levels, Regionals, Interior, and at the very top, the Sintonia Geral e Final (which we call “Central Management”). Composed of the PCC’s ranking leaders, mostly housed together in a single prison, Central Management has final authority over the entire organization inside and outside prison. We observe this authority in the communiqué (salve geral) and “aid bank” documents discussed below.

Journalistic accounts and the MPE’s analysis (DJSP 2015) report that beneath Central Management lie four main branches, also coordinated by sintonias: the prison system (sistema), the “street” (rua), other states beyond São Paulo (estados), and a “support” branch (apoio) overseeing numerous specialized sintonias. Footnote 7 The “street” branch has eight geographic subdivisions: five for the capital city and one each for the São Paulo suburbs (ABC), the port city of Santos and coastal lowlands (Baixada Santista), and the remainder of the state (Interior).

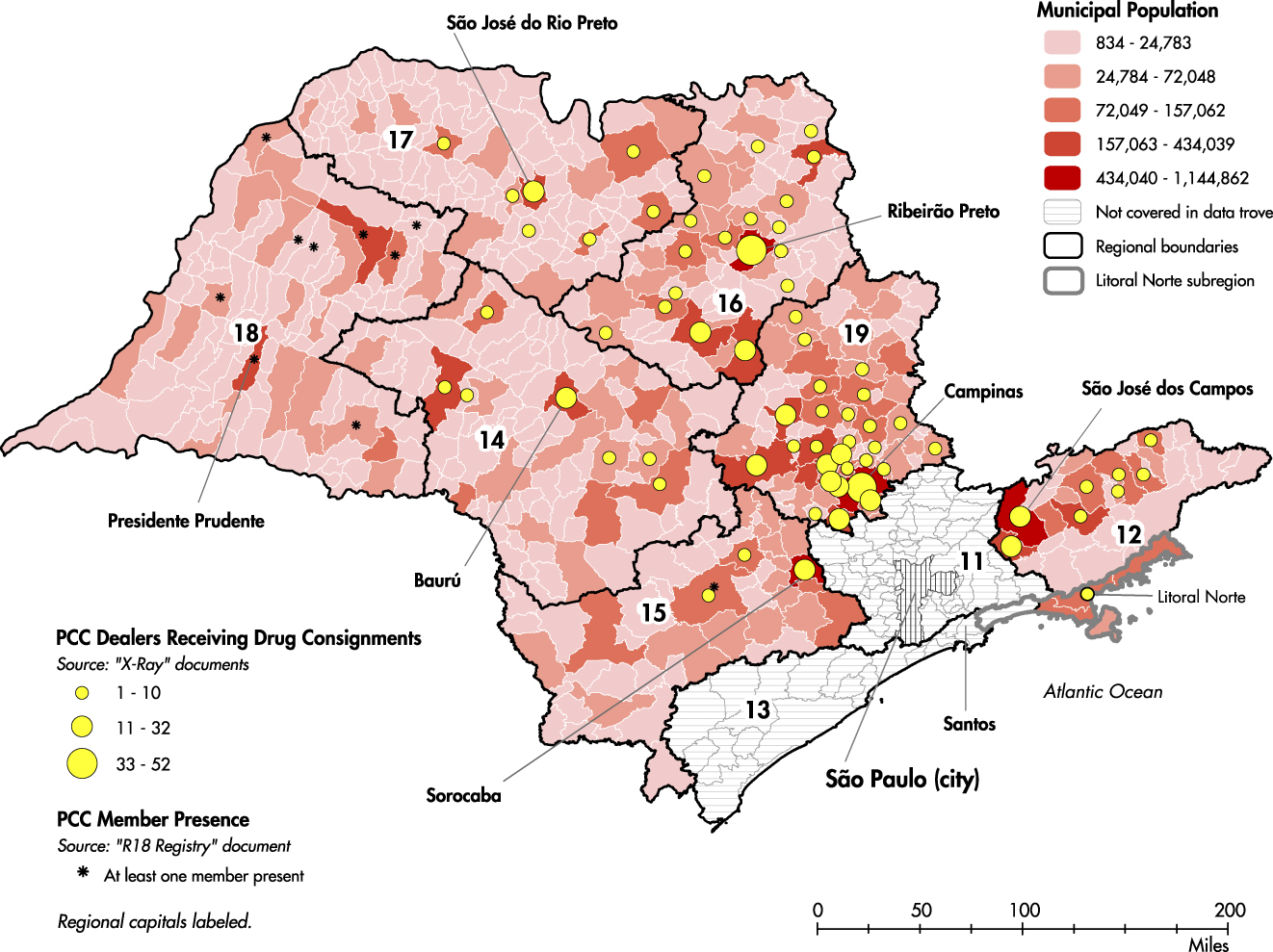

The PCC’s division of the Interior into Regional subunits follows São Paulo state’s official telephone area codes (Figure 3). Our documents refer to the Interior as comprising Regionals 12 and 14–19. Beyond references to “Capital” as an administrative unit, our documents shed no light on how Regionals 11 (Greater São Paulo) and 13 (Baixada Santista) are administered. In the Interior, our data show, Regional-level administrators interact directly with individual dealers in over one hundred quebradas (“locales,” mostly single municipalities in our data); the Regionals answer to the Interior which in turn answers to Central Management, as in the MPE’s analysis.

FIGURE 3. PCC Administrative Structure and Drug Trafficking in São Paulo’s Interior

“Regionals” are defined and numbered by telephone area codes; the Interior administrative unit covers Regionals 12 and 14–19. Circles represent the number of unique dealers (members and affiliates) per municipality who received consignments in our individual-level data. No consignments went to Regional 18 in the period observed, though outstanding debt indicates prior consignments were made. A separate “R18 Registry” lists members there, indicated with stars.

Replicated across this vertical structure is a horizontal division of labor into institutionalized job posts (responsas). At each level, there is a financial, disciplinary, and general manager or council, and other key posts such as bookkeeper (livro, “book”) and messenger (jato, “jet”). Posts are reportedly unpaid (Barbieri Reference Barbieri2014), and our documents contain no record of salaries. One-year bans on holding posts are common punishments, one reason why rotation is frequent.

Our data tell us little about how the PCC operates inside prison. It does confirm that the collection of members’ dues (a monthly fee plus obligatory participation in a raffle) is separate from the administration of the street-level drug trade. Our primary trove covers only the latter, whereas S2 includes files from the dues unit, confirming oversight by Central Management.

Drug Trafficking Operations

Consignment-Based Business Model

Roughly half the trove concerns the financial side of the PCC’s drug operation, detailing an elaborate consignment system for retailing crack, cocaine, and marijuana. Consignment differs from two more commonly observed models of drug retailing: “freelance” operations where individual dealers purchase their supplies up front from wholesalers, and “franchise-model” firms, whose owners pay dealers fixed salaries or commissions and claim residual profits (Johnson, Hamid, and Sanabria Reference Johnson, Hamid and Sanabria1991). Each model has strengths and weaknesses. Levitt and Venkatesh (Reference Levitt and Venkatesh2000) report that the takeover of a Chicago drug market from a gang employing a freelance model by a more sophisticated gang using a franchise model led to a tripling of profits; they attribute this to the severe credit constraints endemic to freelance systems. Hagedorn (Reference Hagedorn1994) also finds centralized, business-model retailing operations to be highly profitable, but more visible and hence vulnerable to law enforcement, and less adaptable to changing circumstances.

Similar dynamics prevailed in many Brazilian cities, including São Paulo prior to the PCC’s widespread involvement, where the concentration of retail drug markets varied as smaller firms expanded into freelancers’ territory while larger firms fell prey to repression and succession battles (Lessing Reference Lessing2008). For decades the key exception was Rio’s CV, which has always been organized on the franchise model, as a confederation of bosses running their own firms, with hierarchies, salaried or commission-based posts, and a local monopoly within his turf (Grillo Reference Grillo2013; Misse Reference Misse2011). While the CV has survived and at times proven quite lucrative, it has suffered both intense militarized state repression and predation by corrupt police, losing considerable ground since 2008.

The PCC’s consignment model constitutes a middle path, alleviating the credit constraints of freelance operations by extending microcredit to dealers, while avoiding the risks and costs of maintaining local monopolies over retail turf associated with hierarchical models.Footnote 8 The consignment model also provides money-making opportunities for members and affiliates while isolating these from the PCC’s collective (and collectivist) endeavors. On the other hand, it creates agency problems, requiring mechanisms to track dealers’ debts and induce timely repayment.

Profits Fund Collective Goods.

How profitable is the PCC’s drug business? The timing of drug consigning and repayment coupled with the relatively short period we observe complicates estimation. Nonetheless, the nonpayment rate on consignment debt appears to be less than the Interior’s markup, suggesting the business is basically profitable. In terms of cash flow, total revenues equal total outlays, with no profits explicitly reported. However, reported expenses include costs of a major transportation network for incarcerated members’ families and other welfare benefits. Overall, we conclude that the business made enough “profit” to finance this network and replenish its drug inventory. We turn to the details.

In our data, crack is by far the dominant economic activity (accounting for 92 percent of revenue), followed by powder cocaine, with marijuana a distant third. The Interior makes wholesale purchases of drugs (100–500 kg in our sample) from unspecified “suppliers.” Drugs are disbursed among the Regionals in lots of 5–103 kg and thence consigned (at a markup) to individual dealers. Dealers can be baptized PCC members (irmãos, “brothers”) or unbaptized “affiliates” (companheiros) and can obtain consignments of virtually any size, for which they incur debt at a fixed per-kilo rate of BRL 8,500 (USD 4,552) for crack and BRL 5,000 (USD 2,678) for cocaine.Footnote 9 No marijuana consignments occur in the period we observe, although small outstanding debts indicate that previous consignments occurred.

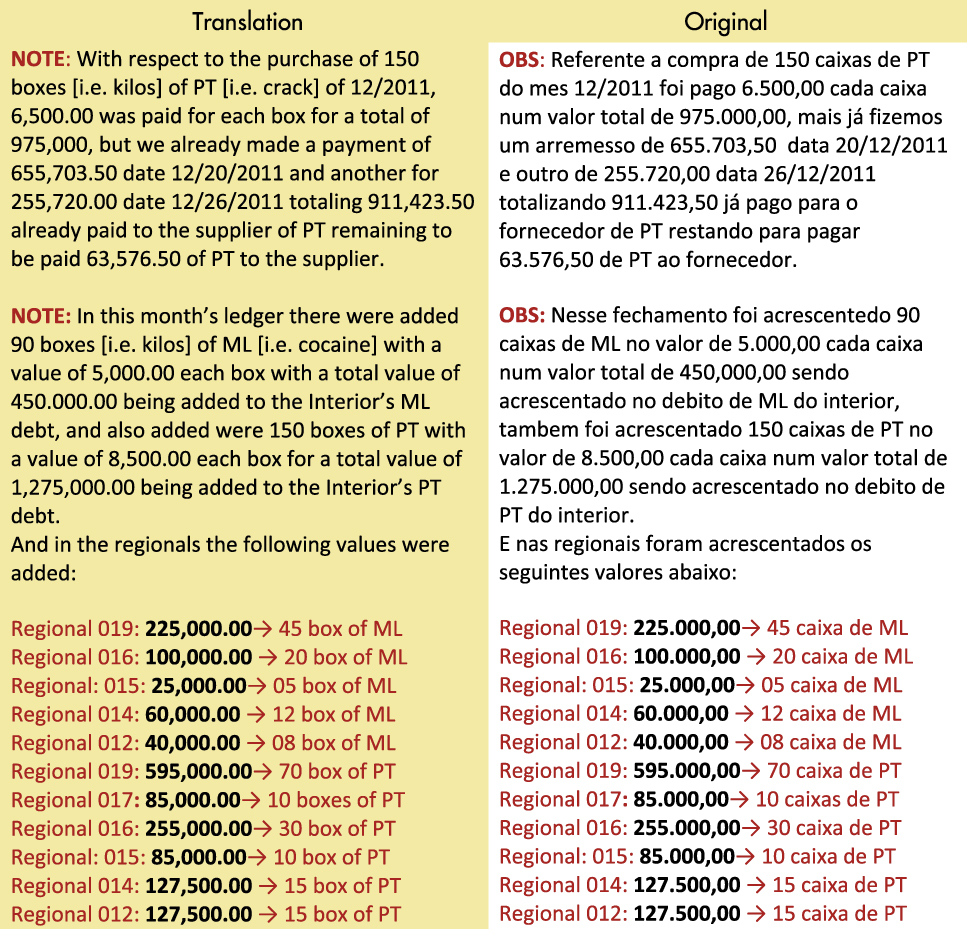

The Interior purchases crack from its supplier at a flat rate of BRL 6,500/kg, retaining a BRL 2,000/kg (30.7 percent) markup. Our data contain one wholesale marijuana purchase of 500 kg at BRL 700/kg but no consignments to dealers, and consignments of cocaine at BRL 5,000/kg but no wholesale purchases, so we cannot calculate either markup. Wholesale purchases are paid in installments; for example, a note in the December 2011 ledger (Figure 4) discusses the purchase of 150 kg of crack at BRL 6,500/kg (for a total of BRL 975,000), stating that two payments have already been made and that BRL 63,576.50 “remains to be paid to the supplier.” The same note details the disbursement of 150 kg of crack to the Regionals, along with their corresponding increases in the Interior’s outstanding debt at the BRL 8,500/kg rate (totaling BRL 1,275,000).

FIGURE 4. Typical Ledger Note Detailing Bulk Drug Purchase by Interior From Unidentified “Supplier” and Marked-Up Disbursements to Regionals

Note: Original formatting and orthography maintained.

The fact that the Interior makes bulk purchases (partially) on credit suggests that the “supplier” could be PCC Central Management, essentially consigning large shipments to the Interior. However, in contrast to Regionals’ debt to the Interior, the documents never mention an Interior debt to Central Management; rather, outstanding debts to suppliers are noted haphazardly in text boxes pasted into ledger spreadsheets, and installment payments are recorded as business expenses. Moreover, the marijuana wholesale purchase is described as “for the Capital” (hence, its disbursement does not appear in our data) while the 120 kg of powder cocaine the Interior had on hand in December was “being disbursed, with 30 to the Capital and 90 [kg] to the Interior.” The only other recorded financial interactions between the Interior and the rest of the organization are two business expenses totaling BRL 57,000 to Central Management for a “project” (progresso) in March.Footnote 10 Many potential financial and logistical arrangements between the Interior, the Capital, and Central Management are consistent with these limited observations.

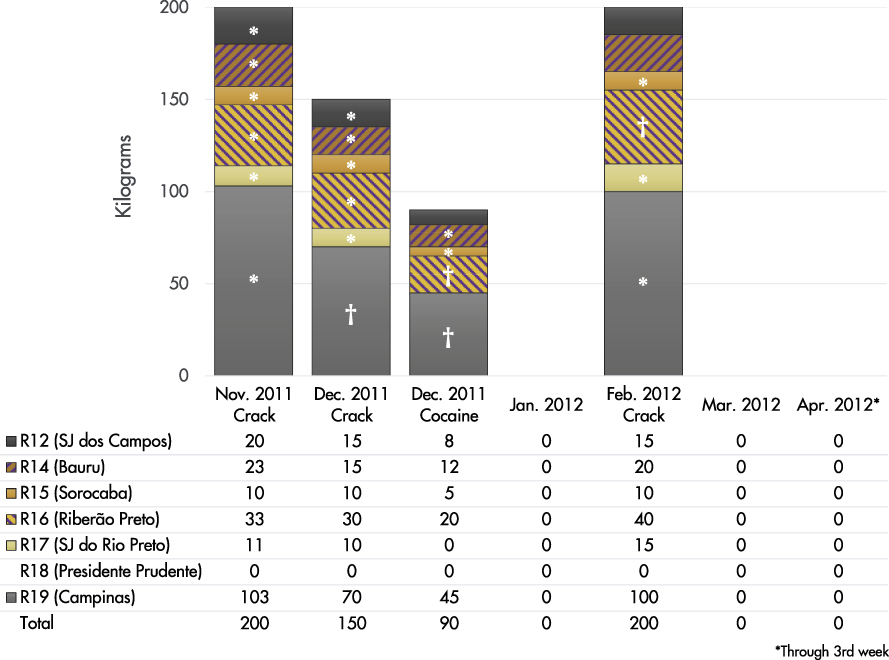

There is significant regional variation in trafficking volume. Regional 19, containing Campinas, the second largest city in the state, was responsible for 47 percent of incoming revenue, while the sparsely populated Regional 18 received no new consignments and made a single small debt repayment. There is also temporal variation, with the largest disbursements in late November 2011 and February 2012, and none in March or the first three weeks of April (Figure 5). Seasonal variation is a plausible explanation: The end of November marks the beginning of summer in Brazil, and the lead-up to Christmas vacation. Summer continues through Carnaval, which fell on February 17–21 in 2012, when drug consumption is probably very high. Work rhythms resume in March, and it is possible that retail drug markets contract accordingly.

FIGURE 5. Drug Disbursements by Regional

Symbols indicate disbursements for which the X-Ray documents provide complete (*) or partial (†) data on individual consignments.

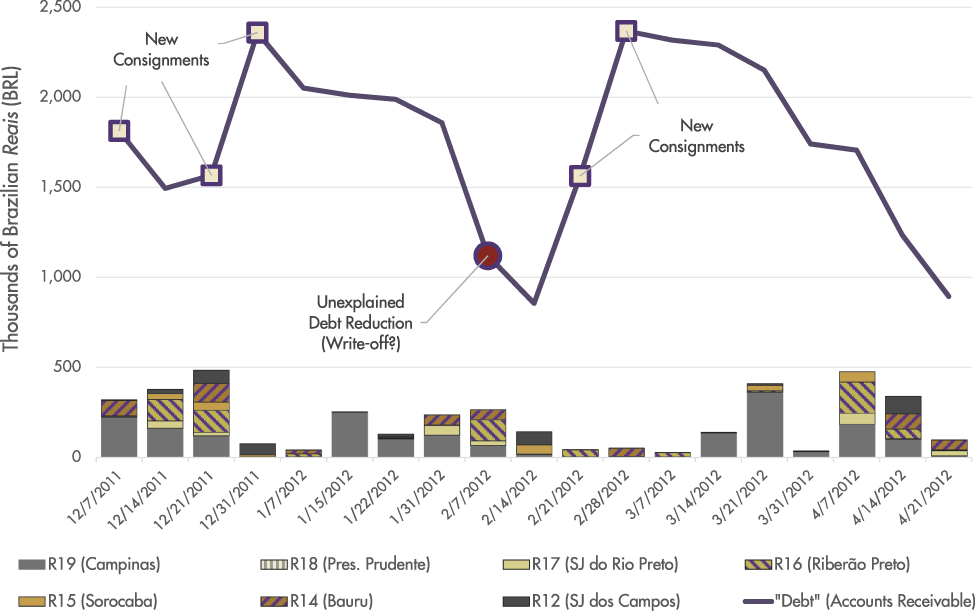

We do not observe dealers’ income from drug sales, nor the markup they charge consumers. We do, however, observe the repayment of consignments by the Regionals to the Interior, which is quite variable likely due to the vagaries of retail-level drug sales and the fates of individual dealers. Figure 6 shows the Interior’s outstanding debt (accounts receivable) and revenues from debt repayments over the period observed. Overall, the Interior took in BRL 3,938,605 and made BRL 3,425,000 in new consignments; an additional BRL 502,647.50 of debt disappears from the books, due, we conjecture, to a write-off of uncollectable debt.

FIGURE 6. Interior’s Total Outstanding Debt (Accounts Receivable) and Debt Repayments by Regional

A large debt reduction in excess of repayments occurs between the January 31 and February 7 weekly ledgers; the January monthly ledger that should explain it is missing, and no other such reduction occurs in the data. We conjecture it was a one-time write-off authorized by Central Management.

Is the PCC’s drug business profitable? The Interior stood to make BRL 2000/kg on the 550 kg it consigned; assuming the same markup (30.7 percent) for cocaine and that the 19 weeks we observe were representative, an upper-bound estimate for yearly profits would be BRL 3,297,895 (USD 1,766,319). However, consignment debts are not always repaid in a timely fashion, or at all.

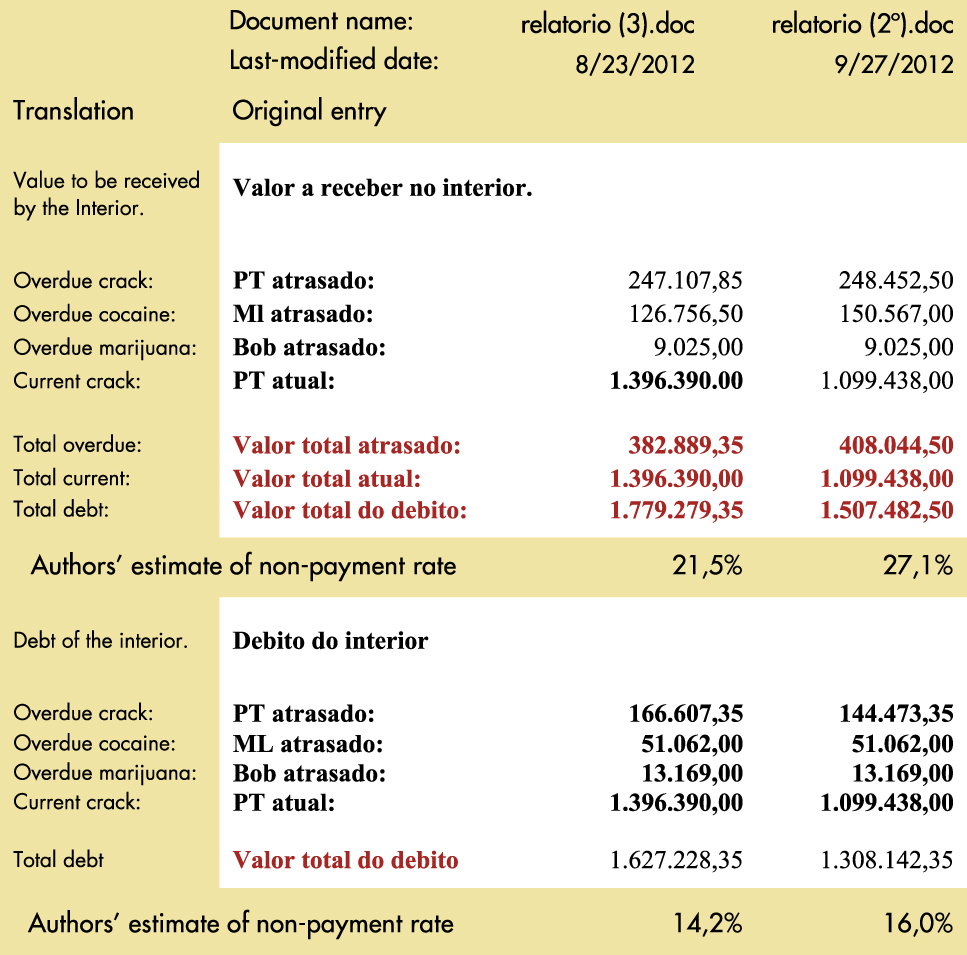

We estimate a nonrepayment rate of 14–27 percent based on an analysis of “relatório” (report) documents. These running tallies of overdue debts among dealers who have gone missing, died, or been arrested or expelled are not consistently organized or dated, and do not tell us the share of loans repaid on-time. However, two reports list “total overdue [debt],” “total current [debt]” (i.e., recently issued consignments) and “total debt” (the sum of overdue and current debt) for the Interior, allowing us to estimate the nonpayment rate as: total overdue/total debt. This estimate is biased, since changes in current debt (new accounts receivable) affect it independently of the repayment rate on prior debts. Moreover, these line items occur twice in each report, consecutively, under different headings, with different values for “overdue debt.” Figure 7 illustrates this, combining the two reports, maintaining the original terms and formatting, and adding translations and our nonpayment rate estimates. We suspect that the bottom entries (débito do Interior) exclude debts considered irrecoverable, but the debt for marijuana increases between the top and bottom entries (the Regional subtotals show similar increases for crack and cocaine). Regardless, most of the estimates fall below the 23.5 percent nonpayment rate at which the PCC would break even on its 30.7 percent markup on crack. Since many of these overdue debts had been on the books for over a year, this seems like a manageable level of nonpayment.

FIGURE 7. Estimated Non-payment Rates, Based on Bad-Debt Reports’ Totals for Overdue and Current Debt

Besides our estimates, labels, and translations (shaded), the original formatting is maintained.

The Interior appears not to owe its overdue debts as accounts payable to Central Management, but it is under pressure to balance its books from Central Management, which can cancel debts it deems uncollectible, as this note in the earliest bad-debt report indicates:

Report of debts among the expelled and of unknown whereabouts who have not settled their debts until today whose values are just bulking up the regional spreadsheets and making it difficult to balance our books, and we are forwarding these names to Central Management, to be analyzed case by case and together with us from the Interior begin to remove from our ledgers this backlog of values that we are not managing to collect.Footnote 11

Our trove also contains a salve geral (a communiqué from Central Management to all members) dated (and last modified) January 23, 2012:

Central Management hereby communicates, by means of this memo, to all those with outstanding debts with the drug trade and finance sector to take responsibility and pay off your debts.

From the date February 20, 2012, those who have not zeroed their overdue debts will be communicated within the central disciplinary sector (nossa disciplina). It will not be necessary for the regional disciplinarian to personally meet each one to let them know, since from now on [if one’s allotted time for repayment] has expired he is automatically suspended[.] Everyone knows their responsibility, and defaulting on debts sets back all of the family’s [i.e., PCC’s] activities.

Around the time of this salve, we observe a permanent and unexplained reduction in the Regionals’ debt to the Interior by BRL 502,647.50, about one-third of the total outstanding. We conjecture that this was a one-time write-off authorized by Central Management, in conjunction with the disciplinary reform described in the salve. We note, however, that no reduction occurred in the Interior’s accounts-payable debt to its wholesale “supplier” (which may or may not be Central Management), which received payment in full for the wholesale purchases we observe.

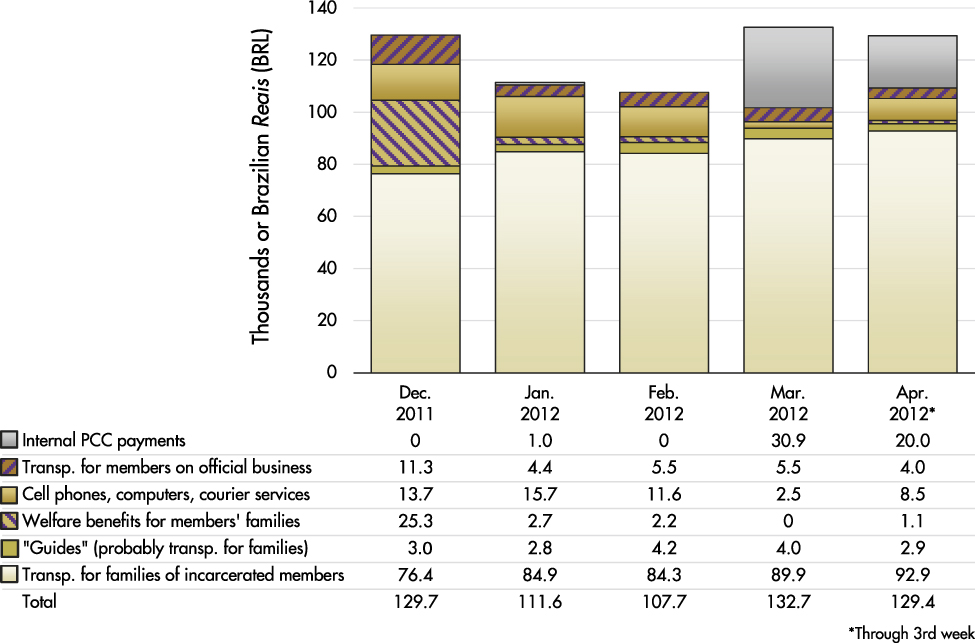

No “profits” appear in the Interior’s cash flows, recorded as revenues and expenses (entrada e saida de dinheiro), but significant expenditures on collective benefits for members’ families appear as “expenses.” In these ledger entries, revenue consists of dealers’ debt repayments, while expenses are divided into wholesale drug purchases—about 90 percent of outflows—and operating expenses that account for the rest. Critically, operating expenses are dominated by expenditures on an elaborate network of vans and busses for transporting families of incarcerated members to far-flung prisons for visitation (Figure 8). These expenditures total about BRL 85,000/month (USD 45,525), while traditional business expenses such as cell phones and courier services account for only about BRL 20,000. The remaining cash on hand, anywhere from BRL 500,000–1,000,000, goes toward bulk drug purchases, often paying down the Interior’s debt to its supplier for prior shipments.

FIGURE 8. “Operating Expenses” (Saida de Dinheiro) in Monthly Ledgers

This heading includes welfare benefits for members’ families, but excludes wholesale drug purchases.

Thus, although the Interior records no profits per se, it clearly directs revenue from its drug business toward collective benefits for members. This collectivist approach is echoed in another document proposing Regional “aid banks” that provide loans of guns and money to members recently released from prison, to help them “get on their feet.” Each bank should have on hand BRL 500,000 (USD 267,800) and a standing inventory of twenty automatic rifles, fifteen submachine guns, fifty pistols, thirty grenades, and twenty revolvers. Gun loans must meet a “principle of proportionality” in which “nobody requests a machine gun to rob a car.” In return, the PCC asks only for “increased commitment to assume existing responsibilities.” The proposal, directed at Central Management, exemplifies how collectivist norms infuse the PCC’s rhetoric and praxis: By establishing these banks, the proposers write, “The family puts the theory of equality into practice, with criminals aiding criminals, recovering the spirit of struggle surrounding our organization.” A note from Central Management approving the project suggests this appeal was successful.

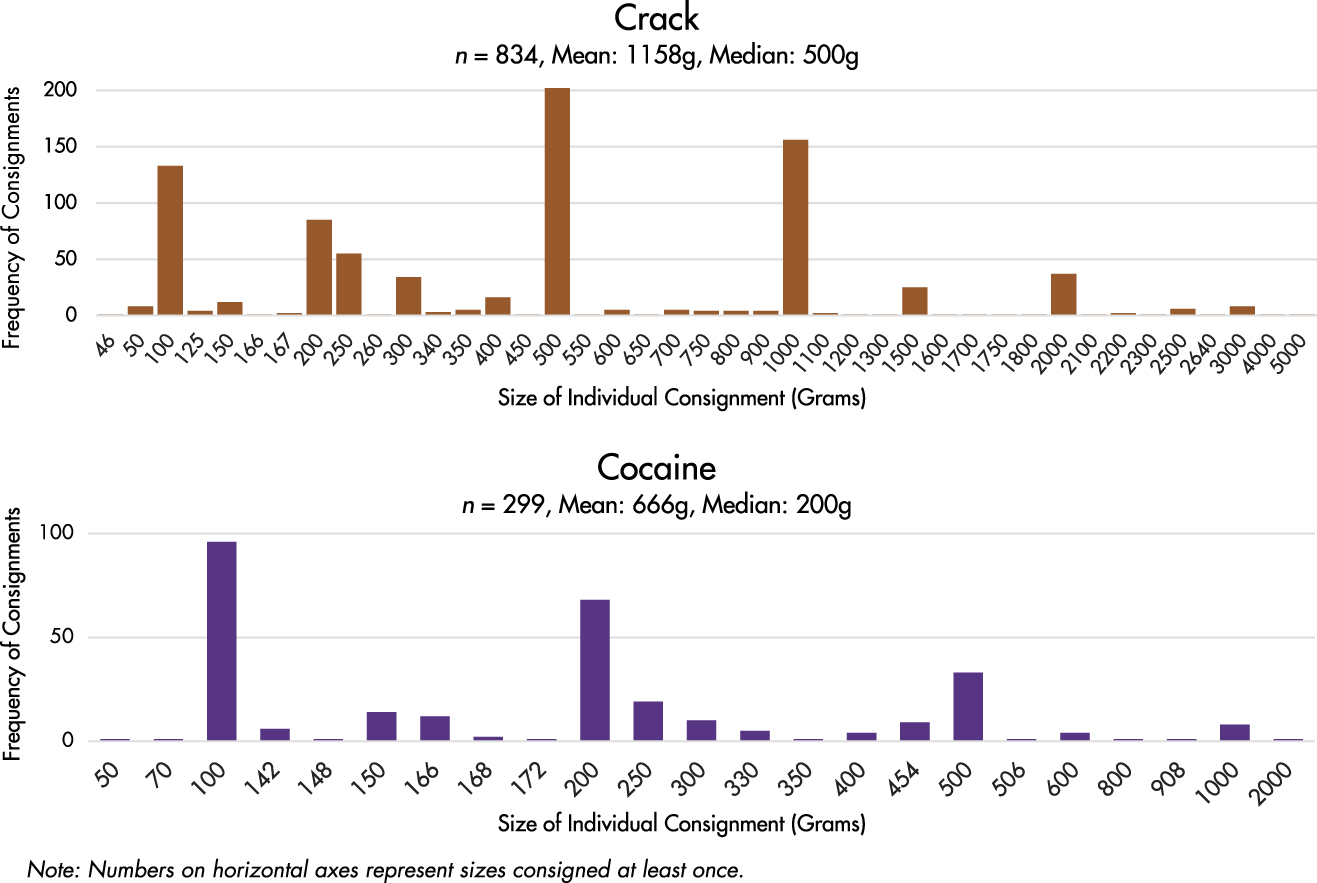

FIGURE 9. Histograms of Drug Consignments to Individual Dealers by Size

Competitive Retail Drug Markets.

The “X-Ray” documents shed light on the structure of drug markets in the Interior. Each records individual consignments to dealers, organized by municipality, for a single drug disbursement (crack or cocaine in our trove). These are compiled first by Regional bookkeepers, then merged into a master document for the Interior. We have the complete master document for the November 2011 crack disbursement; in the other four cases, we are missing X-Ray documents for some Regionals (Figure 5).

Pooling the available X-Ray documents, we observe 1,134 consignments to about 500 individual dealersFootnote 12 operating in 89 municipalities (Figure 3). These are conservative estimates, since there are likely active dealers in other municipalities who did not receive consignments in these specific disbursements. In particular, Regional 18 received no consignments but carried debts, indicating that it sometimes receives consignments. Including the municipalities mentioned in a Regional 18 membership registry (the only such registry in our trove) and the “bad-debt reports” yields 117 municipalities with PCC activity. As Figure 3 reveals, PCC activity is concentrated in the most populous municipalities, encompassing roughly 14 million people, or about 69 percent of the Interior’s population.

The median and modal consignments for crack were 500 g, with 100 g, 200 g, and 1 kg consignments also quite common. However, many odd-sized consignments (e.g., 46 g or 2640 g) occur, suggesting that dealers can request any size consignment they wish. Cocaine saw smaller consignments overall, though this could be due to the limited sample size (one disbursement). Figure 9 plots histograms; numbers on the horizontal axes represent sizes with at least one observation.

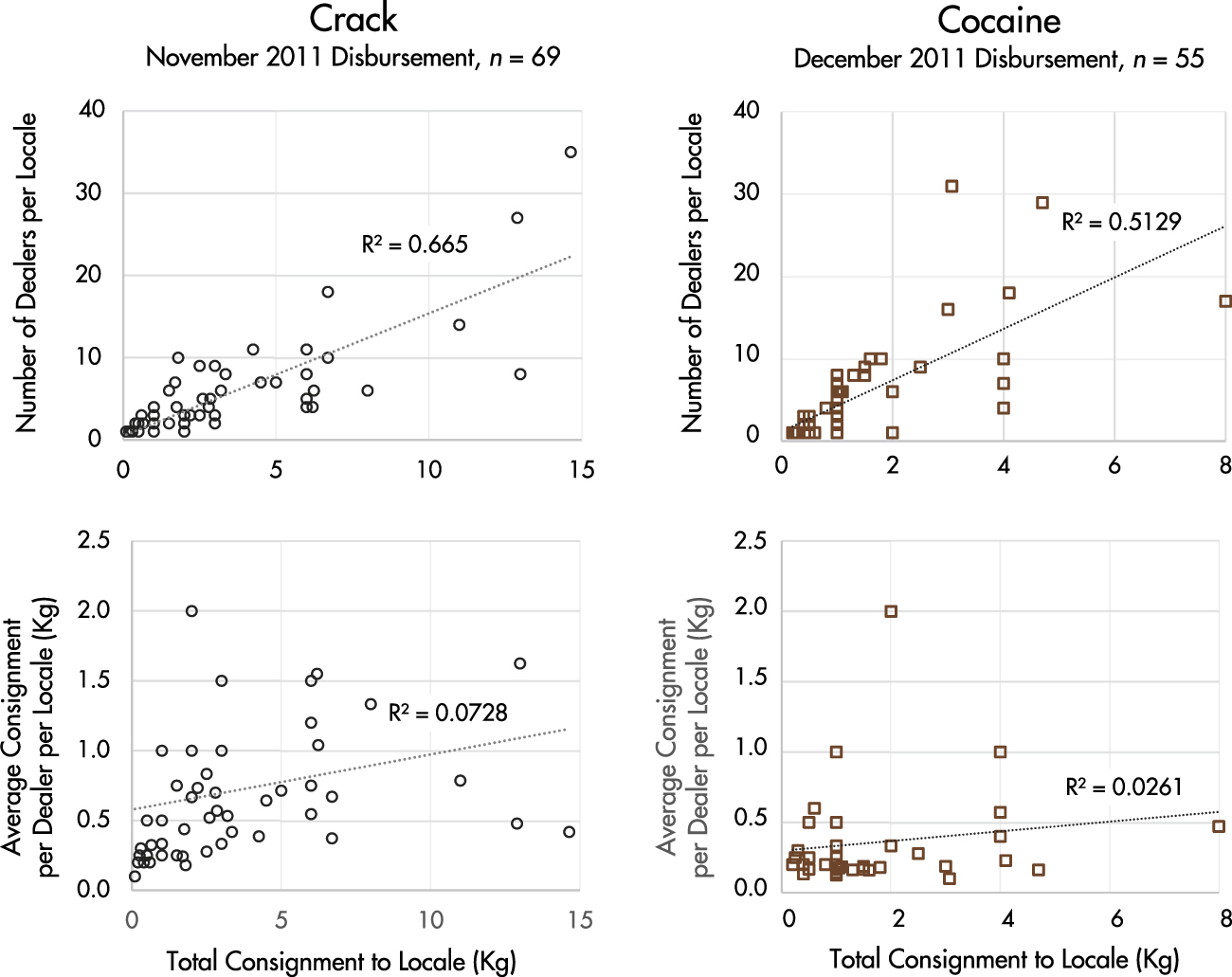

Retail drug markets appear to be relatively competitive. We analyze the crack disbursement for which we have complete consignment-level data (November 2011), as well as the single cocaine disbursement (December 2011). Figure 10 shows that for both drugs, the number of active dealers in each of municipality is correlated with the total amount consigned to that city so that larger markets have more dealers operating. Consequently, the degree of concentration (i.e., the mean consignment per dealer operating in each locale) is essentially uncorrelated with the total size of consignments to that locale. In fact, the “biggest fish” seem to operate in smaller ponds. These data corroborate Feltran’s (Reference Feltran2018) claim that the PCC does not attempt to monopolize retail trade.

FIGURE 10. Number and Average “Size” of Dealers per Municipality

Points represent locales (quebradas, in our sample almost all municipalities) that received drug consignments in the respective disbursements. The top panels show how many dealers received consignments in each municipality; the bottom panels show the average consignment per dealer in each municipality.

Discipline and Punishment

Internal discipline is a challenge for all organizations, but it is a critical one for the PCC’s drug operation because of dealers’ temptation to default. While we might imagine repayment, and gang rules in general, being enforced at gunpoint, there are reasons to avoid extreme punishment. Dealers face great uncertainty and risk, and outcomes are not perfectly correlated with effort. Under those circumstances, overly harsh punishments can encourage exit. More broadly, the PCC’s normative mission centers on proceder, or proper criminal comportment (Biondi Reference Biondi2016; Marques Reference Marques2010); its moral authority could be undercut if punishment were seen as arbitrary, disproportionate, or vindictive.

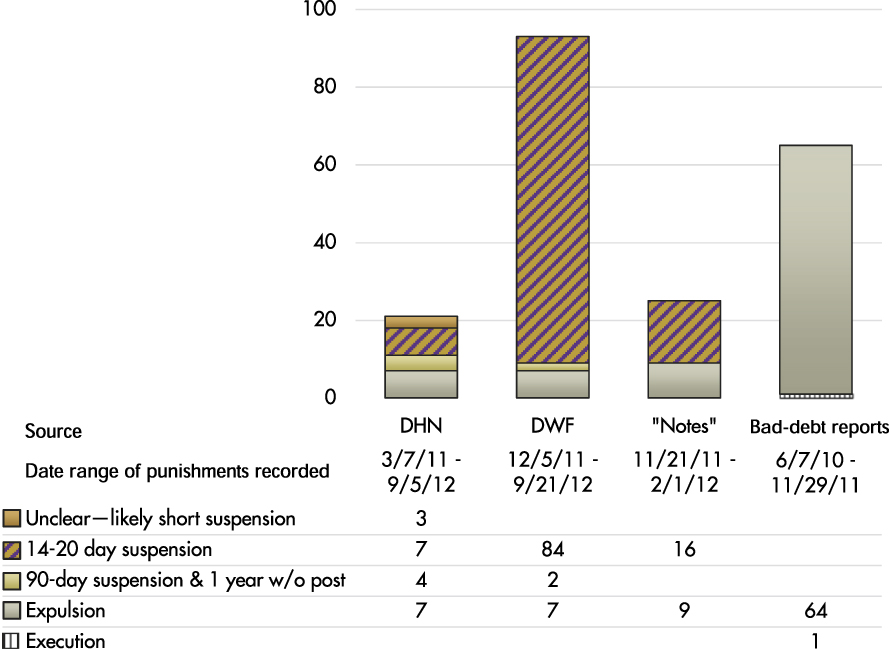

We present two main descriptive findings. First, the PCC, at least in the Interior during the period observed, relies overwhelmingly on suspensions and expulsions. Of the 203 individual punishments documented in our trove, only one—an execution—involved physical violence. Second, the PCC maintains a centralized, queryable system of “criminal criminal records” of members’ and affiliates’ history, including past infractions. Punishment is highly bureaucratized, involving significant, standardized paperwork and numerous mechanisms for administrative review. Though strict and meticulous, the PCC is also clearly concerned with fairness and “hearing out” suspects of wrongdoing. While we lack systematic data for other Brazilian factions, the contrast with Misse’s description of Rio’s CV is startling: “Non-repayment [of debts] is interpreted as fraud, theft, or error, and the debtor on the first repeat offense is killed in a public ritual of cruelty” (Reference Misse2011, 237).

Punishment is Mild

Punishment data come from several different sources within our documents. The most direct evidence comes from the disciplinarian’s handwritten notebook (DHN) and Word files (DWF). DHN contains 21 standardized punishment records, blank templates, and instructions for filling them in, as well as other notes and records. DWF contains 100 Word files: 95 unique, individual punishment records, three duplicate records, and 2 punishment-record templates. Because DWF does not duplicate any records from DHN, while both cover punishments that occurred from late 2011 through September 2012, we suspect the disciplinarian was still digitizing the records in DHN when he was arrested in early October. Another file, “Anotações do Caderno Parte 1,” henceforth “Notes,” contains 25 additional unique records from November 2011 through January 2012. These three sources provide the best measure of the relative proportions of different punishments meted out over time. Additionally, the bad-debt reports (relatórios) mention punishments in the context of overdue debts belonging to members who have been expelled or killed; as such, they capture only a subset of total expulsions and executions, and exclude suspensions entirely.

We coded the punishments recorded in these four sources by type (Figure 11). The overwhelming majority of punishments are 15–20 day suspensions, but a significant number of expulsions also occurred. This is particularly true of the period covered by the bad-debt reports.

FIGURE 11. Punishments Recorded in Disciplinarian’s Handwritten Notebook (DHN) and Word Files (DWF), “Notes” File, and Bad-Debt Reports

Date range of punishments recorded within each source as noted.

No executions appear among the DHN, DWF, and “Notes” files; we suspect that none occurred during the periods covered, but cannot rule out the possibility that executions occurred but were not recorded alongside other punishments. However, the bad-debt reports do document an execution, strongly suggesting that the PCC does not systematically hide violent punishments. Moreover, this likely represents all cases of executed debtors, because these reports detail uncollectable debts to be written off by Central Management, and, as the authors note, “we know that the debts of killed members are automatically written off.” Executions of members without debts would not be reported here, but we suspect such executions are rare, since theft from the organization is a prime motivation for execution. More broadly, the entire trove evinces the PCC’s fervor for recordkeeping, suggesting that, like many regimes, it keeps careful track of even its most repressive actions. In any case, only one out of 203 punishments in our data corresponded to an execution.

Most punishments were the result of the PCC’s automatic, graded punishment system for overdue drug debt, laid out in this template from DHN.

Members: first suspension is 15 days. If they pay, they’re back, if they don’t pay they’re out of the Comando.

Second suspension: 90 days automatically and 15 more days to pay up. If they don’t pay, they’re out.

Third suspension: Automatic Expulsion. And they enter an “affiliate’s twenty-day suspension.”

“Affiliates” are immediately subject to twenty-day suspensions when they do not pay.

The January 2012 salve quoted above suggests that this automatic-suspension policy was new, although numerous first suspensions occur in the months prior as well.

Expulsion usually comes as an automatic response to nonpayment of debts, but we also observe expulsions for being “out of touch” (falta de sintonia), and for lack of “vision,” “responsibility,” and “transparency.” Expulsion is considered a major punishment and bureaucratic safeguards are in place to ensure that it is not wrongfully applied, as a note in DHN explains:

All Expulsions must be sent through a disciplinarian or general manager. Never record an Expulsion reported by a member who does not hold a post (responsa) nor without the knowledge of Central Management or of the Regional. … We bookkeepers should never record an Expulsion without first having the Summary (Resumo) from Central Management.

Multiple references to the Resumo, in our trove and interviews, indicate that it is a mechanism by which Central Management both authorizes individual punishments and conveys the relevant information to branch officials, including bookkeepers. We now explore the PCC’s information-sharing mechanisms.

Centralized “Criminal Criminal Records” Support Voluntary Reporting

The very production and centralization of the punishment records in our trove constitutes an important empirical observation. All large organizations face the challenge of keeping track of members’ performance; for criminal organizations the challenge is exacerbated, since records can be seized by authorities and used as evidence. Many gangs maintain, at best, a membership roster, with reputation based on collective memory, word of mouth, and codes of learned behavior (Gambetta Reference Gambetta2009). This can become problematic in large, dispersed organizations.

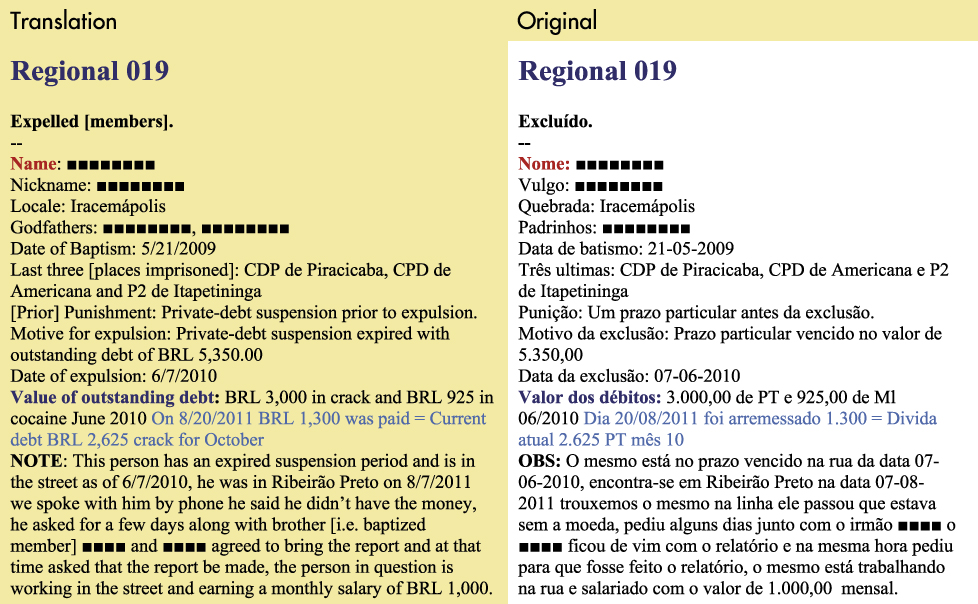

The PCC, in contrast, has developed a system of uniform personnel records consisting of standardized data fields covering individuals’ history with the organization; these (empty) fields compose the punishment-record templates in our trove (Figure 12). These same data fields appear in other PCC documents, particularly when a member or affiliate comes under scrutiny. Because these data “follow” individuals, and because they include previous punishments (punição anterior)Footnote 13 and the bureaucratic processes that accompanied them, we call them “criminal criminal records.”Footnote 14 While we lack similar data for other gangs, intelligence officials in seven Brazilian states believe that no other faction approaches this level of recordkeeping. One leader of a CV-allied faction admitted having difficulty maintaining even a basic roster, and being unable to incorporate “previous punishments” and other data fields.Footnote 15

FIGURE 12. “Criminal Criminal Records”: Data Fields in Punishment-Record Templates

Explicit instructions accompany the templates in DHN: “When registering a suspension, all personal data is required. Name, nickname [etc.]… if he’s received a punishment by the family [i.e., the PCC] and if so, its locale, motive, and date.” For expulsions, additional information is required: motive, locale, date, and acompanhamento (“oversight”), a list of PCC officials involved in judging the case, running from the Regional disciplinarian up through Central Management, whose authorization must be conveyed via the Summary (Resumo). The two digital templates in DWF appear to further standardize PCC recordkeeping: All subsequent punishment records (by last-modified date) follow these templates, while earlier ones present the same data in varied formats. The disciplinarian himself may have innovated, or simply adopted, a systemwide innovation.

These data reappear when individuals are mentioned in other documents. For example, the bad-debt reports contain 63 unique records of expulsions for overdue debt. Although these reports focus on tracking and recovering debts rather than punishment per se, they recapitulate key data from individuals’ “criminal criminal records.” Figure 13 provides an anonymized example, with data-field names and key entries translated, and the original formatting preserved.

FIGURE 13. Example of “Criminal Criminal Record” Data Reappearing in a Bad-Debt Report

This individual’s prior punishment for a private debt seems to have influenced his expulsion in June 2010. He was contacted 14 months later by the PCC and ended up paying back a third of his outstanding debt.

These cross-listings strongly suggest that “criminal criminal records” can be queried by members, at least those occupying posts. For example, the entry in Figure 13 was prepared sometime between July 2011 (the last date mentioned in the entry) and September 27, 2012 (the file’s last-modified date), but references an expulsion from July 2010. File metadata reveals that these reports’ authors are not the same as the punishment records’, and the former were unlikely to know the relevant facts offhand. Key elements of members’ “criminal criminal record” are similarly reproduced across PCC documents, suggesting that the underlying data are accessible, possibly by requesting a Summary from Central Management.

Lessing’s interviews with imprisoned PCC leaders in other states corroborate this view. One mentioned a queryable “center” (central) of personnel records in São Paulo.Footnote 16 The other explained that newly arrived inmates are expected to report the information in their “criminal criminal record” to local PCC representatives, including “previous punishments”:

BL: …I’m asking because I’m doing a study with [PCC] documents from São Paulo, … and they always note “previous punishments.”

I: “Previous punishment” is asked about. If someone shows up and doesn’t report it, “Ah, I have a punishment in São Paulo but I won’t report it here.” But management is centralized (Mas a geral é uma só).

BL: You would have a way to find that out?

I: Absolutely. […] We can find that out here. I’m just the representative for this wing, but there is a General Manager (geral do estado) for the whole state, he has our registry (cadastro) and it will go into the Summary (Resumo), the Summary records all of Brazil, it will be noted there in the registry, dates of baptism by his godfathers…

BL: Will “previous punishments” also be recorded?

I: “Previous punishments,” absolutely. Every act is recorded there.

BL: But you guys, being in other states [i.e., not São Paulo], do you have a way to consult it?

I: We do.

BL: Send a message, “Hey, can you look this guy up?”

I: We do, we do.Footnote 17

Intriguingly, this ability to query—combined with moral sanction for lack of transparency—seems to induce an equilibrium in which truthful provision of personal information is the dominant strategy, and querying is rarely necessary:

I: Every time a member or affiliate arrives here in our wing, he comes to us, and if he has something to tell us, if he has a debt with the Comando, he will pass along the information. Transparency speaks volumes in a situation like that. If you arrive here full of lies, and later we get confirmation that those situations were true that you failed to tell us about, that generates a different type of situation. […]

BL: You won’t trust the guy as much?

I: Right. […] All of us, whenever there is contact. If I were released today, I’ll find the Comando wherever I end up, I will seek out the representative of that city, that neighborhood, that disciplinarian, that prison unit, and I’ll pass along my record (cadastro). I will have to act with transparency, because a Comando member is like that, he is transparency, he cannot lie.Footnote 18

Our data support the idea of a voluntary-transparency equilibrium, documenting multiple expulsions for “lies” or “lack of transparency,” and a possible example of the equilibrium at work, from a note on an uncollected debt from an imposter:

…Upon incarceration he opened his heart… he told the truth that he wasn’t a member and had been using the name [of a member] while in the street.

With staggering irony, the PCC appears to have built what the state has conspicuously failed to: a true panopticon, in which the possibility of being observed at any time leads all inmates to act as though they were being observed always.

DISCUSSION

We argue that four central empirical findings—the PCC’s consignment-based drug trafficking business, its relatively mild and “sympathetic” punishment regime, and resource-intensive recordkeeping, and its use of profits for collective benefits—are causally interconnected. Analyzed together, they reveal a powerful approach to criminal governance that has probably facilitated the PCC’s unprecedented growth and resilience.

One advantage of the PCC’s consignment model is its potential for flexible, decentralized expansion. Yet, consignment only works if dealers regularly repay their debts in a timely fashion. Dealers have incentives to pay up and receive the next consignment, but in the rough-and-tumble world of drug dealing, there are countless frictions that can make delay or default tempting, hence the need, articulated in our documents, to “lean on” debtors. Yet, the very decentralization that consignment permits, particularly in “Frontier” areas such as São Paulo’s Interior, means that physically coercing individual street dealers could be costly or impractical.

The PCC has an elegant solution to this agency problem. First, it is inadvertently aided by the state, which—through its mass incarceration policies—directs significant resources to arresting dealers and bringing them to places where the PCC can easily punish them: the prison system. Crackdowns that drive up incarceration rates (and at 530 per 100,000 residents in 2016, São Paulo state’s is very high) raise dealers’ expected probability of being sent to a PCC-controlled prison and hence increase the downside risk of running afoul of its disciplinarians (Lessing Reference Lessing2017).Footnote 19

Even in prison, though, the PCC metes out little physical punishment. We observe dozens of individual records of dealers imprisoned while holding debt; among these, only suspensions and expulsions are noted. This corroborates Dias and Salla’s (Reference Dias and Salla2013) finding that graded punishments replaced more violent and arbitrary sanctions within prison. Here too, the PCC benefits from the actions of the state, which—despite extensive prison construction—maintains a burgeoning inmate population (over 237,000 as of 2016) in conditions of intense overcrowding, precarious infrastructure, and insufficient and/or abusive guards. Under such conditions, the prospect of losing PCC protection and welfare is a powerful incentive for repayment.

The PCC’s internal disciplinary system further amplifies the force of nonviolent punishments in two key ways. First, in combining automatic suspensions with a system of jury trials and appeals, the PCC guarantees procedural justice (Tyler Reference Tyler2003): Sentences are handed down in a consistent, transparent, and nonarbitrary way. Mechanisms to avoid false positives ensure that only the guilty are punished.

Second, the PCC’s “criminal criminal records” guarantee that infractions and resulting punishments become and remain common knowledge. PCC members, and potentially affiliates, can learn about someone’s past actions and make accurate inferences about their future reliability. Suspensions may carry only a minor direct cost in missed opportunities for profit, but, like low credit scores, they hurt members’ reputation in the eyes of potential future collaborators.

Do members and affiliates in fact stigmatize the punished? Within prison, Dias and Salla note that even brief suspensions involve “losing social status before the prison population.” (Reference Dias and Salla2013, 404). In the urban periphery, Feltran’s (Reference Feltran2010) account of a PCC-led trial of a non-member, accused of embezzling from a local non-PCC drug firm, is illustrative. The accused’s defense was strong and courageous, but a previous 30-day suspension counted against him, and he was sentenced to a beating. The true punishment, however, was the stigma attached to his conviction, as a relative explained: “He was completely demoralized in the world of crime, and there was no way he could return.” (Quoted in Feltran Reference Feltran2010, 65). Our data suggests that this example is not atypical: Of the 63 expulsions recorded in the “bad-debts” documents, 27 note that the expelled member fled his home municipality and could not be located.

Of course, meticulous recordkeeping alone does not guarantee fairness or induce compliance; after all, many authoritarian regimes have kept detailed records of genocide, mass killings, and torture.Footnote 20 Rather, recordkeeping works in conjunction with an efficacious and procedurally fair “criminal criminal justice” system to create the conditions for widespread voluntary compliance (Tyler Reference Tyler2003). The resulting system of governance, we argue, approximates Weber’s ideal type: “[legitimation of] domination by virtue of ‘legality,’ by virtue of the belief in the validity of legal statute and functional ‘competence’ based on rationally created rules.” (Reference Weber1946, 79).

Weber’s concepts are meant to be scientific and observable (Reference Weber1968, 215), but we rarely know whether subjects truly believe in the legitimacy of the authorities to which they submit (Wedeen Reference Wedeen2015, xiv). PCC specialists disagree about this very point: In Biondi’s (Reference Biondi2016) prison ethnography, PCC authority derives entirely from shared norms, whereas other scholars emphasize fear of punishment (Dias and Salla Reference Dias and Salla2013; King and Valensia Reference King and Valensia2014).

While our data cannot decide the question, our theory illuminates the potential complementarity between the PCC’s collectivist norms and its “criminal criminal justice” system. In our story, members know that suspensions and expulsions (1) reflect accurate assessments of behavior, (2) are carefully recorded and can be queried, and hence (3) are generally voluntarily reported to unfamiliar members, who will then (4) treat infractors accordingly. While such a system could plausibly be sustained on a purely materialistic, instrumental basis, norms can buttress each step: If the behavior in question is seen as unethical (and not merely prohibited), members are more likely to stigmatize transgressors. Punishment by an unreliable tyrant can be quite harsh, but it will carry little additional stigma if others perceive the accusation as potentially false or the violated rules as arbitrary. Punishment by a decentralized and deliberative network of dedicated volunteers committed to a clear set of rules can be mild precisely because its mere application is a trustworthy signal of rule-breaking to others. In the PCC’s case, those rules reflect shared norms of integrity and equanimity that, when collectively practiced, produce a better criminal underworld for everyone. Thus, their violation induces, in an organic way, a strong social stigma. Obsessive recordkeeping and a norm of transparency ensure this stigma will be long-lasting and far-reaching.

Supporting the idea that norms play a key role in sustaining criminal governance, new factions throughout Brazil, often formed in opposition to PCC expansion, nonetheless borrow and adapt its normative language and appeals. As one informant from a state only partially dominated by the PCC told Lessing, “The PCC may not have won the war of territory, but it won the war of ideas.”Footnote 21 The “aid bank” document discussed above, and at length in Denyer Willis (Reference Denyer Willis2014), exemplifies this: Its authors invoke the PCC’s moral precepts to advocate, apparently successfully, for implementing a criminal redistributive mechanism.

To clarify, our claim is not that legitimacy and a perception of fairness are necessary to generate compliance nor that they always induce more compliance than brute coercion, at least locally. Had the PCC adopted harsher punishments, it is quite possible that nonpayment rates would have been lower. Indeed, many expelled members simply flee rather than paying up; in one case, a member accused of unauthorized killing—an infraction punishable by death—is given a chance to collect evidence for his defense prior to PCC trial and takes the opportunity to flee. Such under-punishment likely motivated the January 2012 salve, which made punishment marginally harsher in response to excessive outstanding debts. Yet, this readjustment did not affect the overall mildness and procedurally transparent aspects of the PCC disciplinary regime. This suggests that Central Management takes a profit-satisficing approach, adjusting the harshness of its punishment practices to maintain basic profitability, but stopping short of draconian punishments that might undercut perceived legitimacy.

This hypothesized prioritization of legitimate governance and procedural justice over profits finds evidentiary support in the PCC’s bookkeeping practices. Punishment records are decidedly more detailed and meticulous than the purely financial documents; the bad-debt reports—containing both financial and personnel data—offer the clearest evidence. Whereas each individual’s “criminal criminal record” is dutifully reproduced, including negotiated repayment schedules, excuses given, rumored whereabouts, and PCC personnel involved in punishment decisions, the actual debt totals are inconsistent and frequently differ from the sum of individual outstanding debts. The individual consignment data contain clerical errors; the expense accounting in the ledgers is haphazard; and one major reduction in outstanding debt goes unaccounted for. However important bookkeeping is to the PCC’s successful scaling up of drug trafficking operations, financial efficiency does not seem to drive its embrace of bureaucracy.

All of this suggests that the PCC views drug profits less as an end than as a necessary means to strengthen and expand the organization, a view consistent with its use of those profits to fund collective goods such as transportation for members’ families. Indeed, the PCC seems to have deliberately designed flexible business-side rules in order to produce a perception of equanimity and fairness. The severest punishments are reserved for betrayals of core organizational values; if that means a somewhat higher (but manageable) level of non-payment on debts, so be it.

This view flows from the data in our trove, but is consistent with Marcola’s testimony concerning the “democratizing” reforms he implemented after his 2002 coup. These were meant to put an end to both the violence being meted out by the PCC’s founders and the extortionate “pyramid scheme” it supported:

“The leadership was drunk with its own success […] and ended up committing atrocities worse than those they had sought to restrain […] It was a huge abuse of power, 80 or 90 inmates assassinated per year. […] From the moment that I distributed it, that power was divided, the pyramid ended… from that moment on, my leadership also ended” (Marques Reference Marques2010, 322–4).