Introduction

A common refrain among political scientists is that courts can only influence politics and policy if they are solicited in disputes. In this view, courts are inherently constrained as public institutions by their reactive nature: Unlike legislators or executives who can set their own agendas, judges “have no self-starting mechanisms” (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1977, 53) and must wait for other actors to litigate controversies before them to render decisions (Becker and Feeley Reference Becker and Feeley1973; Hall Reference Hall, Epstein and Lindquist2017; Keck and Strother Reference Keck and Strother2016).

We challenge this narrow understanding of judicial impact by investigating the surprising politics behind what we call the shadow effect of courts: policy makers preemptively altering practices or policies in anticipation of possible judicial review. We propose a comparative theory of shadow effects that distinguishes it from other “radiating effects of courts” (Galanter Reference Galanter, Boyum and Mather1983) and that significantly broadens the scope for inquiry on “the judicialization of politics” (Alter, Hafner-Burton, and Helfer Reference Alter, Hafner-Burton and Helfer2019; Ferejohn Reference Ferejohn2002; Hirschl Reference Hirschl2007; Shapiro and Stone Sweet Reference Shapiro and Sweet2002): If judicial review can influence policy making even where the dogs did not bark, then courts’ political influence may be more encompassing than is often presumed.

To date, the most compelling evidence of the shadow effects of courts has been confined to the context where we would most expect them: The litigious and judicialized United States. In the prototypical site for “adversarial legalism,” policy makers take interest-group litigation for granted and have largely adapted to a judicialized environment (Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2020; Farhang Reference Farhang2010; Kagan Reference Kagan2019). By adopting preemptive policy changes, American policy makers seldom seek to evade judicial review altogether, but rather to survive litigation and to harness the anticipation of adjudication as an instrument of reform (Epp Reference Epp2010; Melnick Reference Melnick1983). In comparative terms, the combination of vigorous litigation and policy makers who defer to or support judicial review renders the US a “most likely case” for shadow effects (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 108; Rohlfing Reference Rohlfing2014, 613). As a result, the existing literature yields insights that may not extend to other countries where litigation and judicial review are subject to greater political resistance, such as civil law and corporatist states (Kagan Reference Kagan1997; Merryman and Perez-Perdomo Reference Merryman and Perez-Perdomo2007; Pavone Reference Pavone2018). Shadow effects would seem even more unlikely for international courts, as most are seldom solicited by interest groups and plagued with frequent government backlashes to their authority (Alter Reference Alter2014; Conant Reference Conant2002; Martinsen et al. Reference Martinsen, Blauberger, Heindlmaier and Thierry2019; Voeten Reference Voeten2020).

Contrary to these expectations, we argue that courts can catalyze preemptive reforms even in more hostile political terrains where interest-group litigation is scant and resistance to judicial review is entrenched. However, both the political process triggering these effects and the consequences for judicial policy making require flipping the presumed link between shadow effects and judicialization on its head.

We argue that when policy makers neither support nor expect judicial interference, noncompliance with legal obligations can fester. In turn, providing judges with an opportunity to legitimate judicial oversight and expose noncompliance can become a powerful threat. Even where interest groups fail to mobilize this threat, an alternative trigger can arise when bureaucratic conflicts within the state push disaffected public officials to consider turning to the courts to gain institutional influence. Government leaders intent on starving courts of opportunities to exercise judicial review may then concede sufficient policy changes to placate disaffected officials and make judicial oversight appear unnecessary for detecting and reforming problematic policies. In other words, instead of shadow effects signaling deferential policy makers supportive of expansive judicial policy making, they signal recalcitrant policy makers’ desire to obstruct courts’ capacity to exercise judicial review. And instead of judges welcoming preemptive reforms in a context where they are otherwise swamped by lawsuits (Feeley and Rubin Reference Feeley and Rubin2000, 75, 101), they may be left lamenting being starved of the cases they need to build their authority (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2019, 327–40). Shadow effects are Janus-faced: They expand the spectrum of indirect judicial influence and can trigger major reforms, but they are hardly an unqualified good for courts.

To illustrate our argument, we trace the politics of resistance to an international court hitherto neglected by political scientists and embedded in a hostile context for judicial impact: The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) Court. At first glance, the EFTA Court would seem decidedly ill-positioned to cast any semblance of shadow effects: Not only is it far less active and powerful than higher-profile international courts (Alter Reference Alter2014), but the largest member state under its jurisdiction—Norway—shares a long-standing history of political opposition to judicial interference with other Nordic countries (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2011; Selle and Østerud Reference Selle and Østerud2006; Wind Reference Wind2010). For years, the relationship between Norway and the EFTA Court has been “troubled” (Fredriksen Reference Fredriksen, Howse, Ruiz-Fabri, Ulfstein and Zang2018, 180). Leveraging this hard case outside the scope of existing theories, we trace the surprising politics behind a major overhaul of a restrictive Norwegian welfare policy that had led to the wrongful jailing of dozens of individuals and the denial of social benefits to thousands more. We demonstrate that this sudden reform was catalyzed by a bureaucratic conflict within the Ministry of Labor and a fierce campaign by government officials to preclude it from enabling the EFTA Court to exercise oversight and build its case law. These findings suggest that the politics of resistance to judicial review that comparative and international relations scholars have hitherto tied to reactive backlash (Abebe and Ginsburg Reference Abebe and Ginsburg2019; Blauberger and Martinsen Reference Blauberger and Martinsen2020; Madsen, Cebulak, and Weibusch Reference Madsen, Cebulak and Weibusch2018; Voeten Reference Voeten2020) or noncompliance campaigns (Conant Reference Conant2002; Martinsen Reference Martinsen2015; Martinsen et al. Reference Martinsen, Blauberger, Heindlmaier and Thierry2019; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008) can also trigger policy reforms without judges ever being solicited—a type of judicial impact as prone to being overlooked as it may be undesired by judges.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows. We begin by defining the shadow effect of courts and distinguishing our argument from existing research. We then justify our case selection of Norway and the EFTA Court, outline a process-tracing methodology to test our theoretical claims, and deploy it in an intensive case study drawing on primary sources. We conclude by highlighting how our findings advance our comparative understanding of judicial impact, resistance to domestic and international courts, and bureaucratic politics. Our conclusion is that even when policy makers successfully weaponize preemptive reforms to forestall judicialization, the shadow effect of courts can still bolster the capacity of reform advocates to hold their governments accountable, incentivize judges to facilitate access to justice, and provoke profound institutional changes within national bureaucracies.

Theorizing the Shadow Effect of Courts

Political scientists have tended to adopt a rather restrictive conception of judicial impact as “policy-related consequences of a decision” (Becker and Feeley Reference Becker and Feeley1973, 213), “impacts that judicial decisions have on politics or policy” (Keck and Strother Reference Keck and Strother2016, 3), “the causal effect of judicial rulings on others’ behavior” (Hall Reference Hall, Epstein and Lindquist2017, 460), and “the effects of judicial decisions” (Volcansek Reference Volcansek2019, 154). Even impact studies illustrating this definition’s narrowness in practice still sometimes embrace it as a theoretical claim (Erkulwater Reference Erkulwater2006, 143; Melnick Reference Melnick1983, 15; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008, 17). In truth, the concept of judicial impact also includes how politics and policy are conditioned by the anticipation of adjudication, irrespective of whether a court is solicited and renders a decision.

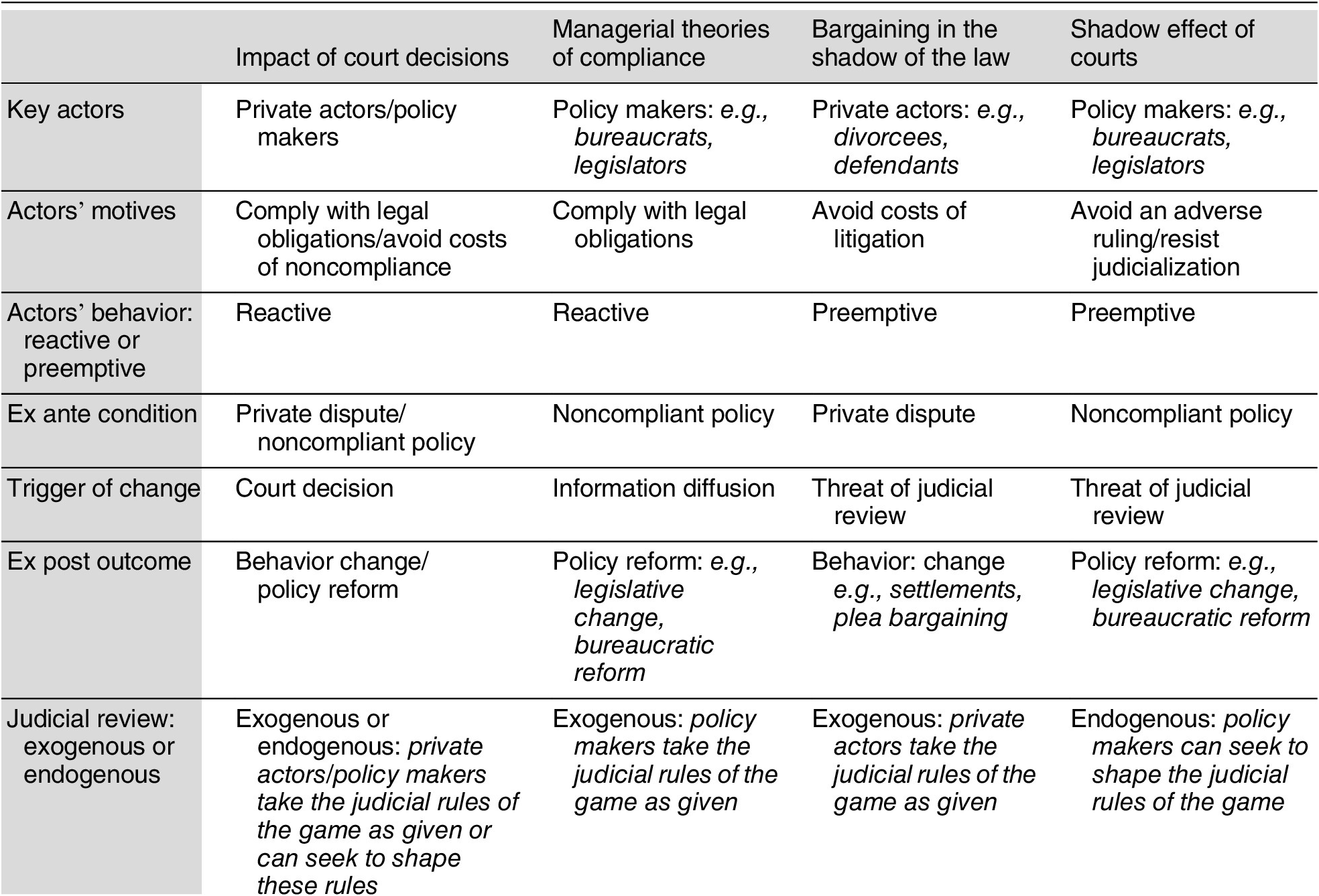

When policy makers such as executives, legislators, and bureaucrats adopt costly changes in practices or policies because of the mere threat of judicial review, we call this the shadow effect of courts. This definition requires further articulation, as it bears similarities to other indirect forms of judicial impact that have also been variously described using the “shadow” metaphor or as “radiating,” “general,” or “feedback” effects (Barnes Reference Barnes2019; Galanter Reference Galanter, Boyum and Mather1983). To this end, Table 1 distinguishes what we mean by “the shadow effect of courts” from related sociolegal concepts.

Table 1. The Shadow Effect of Courts versus Related Types of Radiating Effects

First, unlike the direct and indirect ripple effects of rendered judicial decisions central to implementation studies (Barnes Reference Barnes2019, 150–52; Blauberger and Schmidt Reference Blauberger and Schmidt2017; Erkulwater Reference Erkulwater2006; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2018), we focus on anticipatory actions preceding rulings that may never be rendered. The trigger of change thus shifts from litigation and judicial review to the mere prospect of adjudication. Second, in contrast to how litigation endows private parties with bargaining leverage to negotiate pretrial settlements—often described as “bargaining in the shadow of the law” (Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2020, 481; Mnookin and Kornhauser Reference Mnookin and Kornhauser1979; Stevenson and Wolfers Reference Stevenson and Wolfers2006)—our focus is on policy reforms adopted by political actors that can trigger significant institutional changes. Whereas private parties usually take laws and judicial review as given and adjust their behavior to avoid litigation costs, policy makers are in a position to preemptively shape the judicial rules of the game and the trajectories of lawmaking, as we will see. Finally, in contrast to managerial theories of compliance probing remedial actions by policy makers who become aware that they are violating the law (Chayes and Chayes Reference Chayes and Chayes1993), our focus is not on reactions to information acquired independent of judicial review but on preemptive reforms to circumvent adjudication. As we will show, recalcitrant policy makers may attempt to pass off reforms designed to evade or undermine judicial review as these more benign responses to novel information concerning uncontested legal obligations.

To date, the most compelling evidence for the shadow effect of courts has been confined to the US. This is unsurprising, given the pervasiveness in the US of adversarial legalism—“policy making, policy implementation, and dispute settlement by means of party-and-lawyer dominated means of legal contestation” (Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2020; Kagan Reference Kagan2019, 3). As a “litigation explosion” and “flood of [judicial] decisions” followed in the wake of the civil-rights movement (Frymer Reference Frymer2008; Galanter Reference Galanter1986; Melnick Reference Melnick1983, 4), an “explosion in the fear of liability” diffused across levels of government (Epp Reference Epp2010, 3). Policy makers grew accustomed to “prospectively trying to anticipate” judicial rulings based on past precedents (Silverstein Reference Silverstein2009, 65), a finding confirmed by case studies of major policy reforms (Melnick Reference Melnick1983; Reference Melnick1994) and econometric studies of bureaucratic and legislative behavior (Canes-Wrone Reference Canes-Wrone2003; Langer and Brace Reference Langer and Brace2005). While movement activists and interest groups were the primary catalysts of the threat of judicial review (Epp Reference Epp1998; Reference Epp2010; Frymer Reference Frymer2008; Kagan Reference Kagan2019), they exploited favorable political opportunities. Bureaucrats and public managers often “enthusiastically joined with external activists in using the threat of liability as a lever of reform” (Epp Reference Epp2010, 3; Feeley and Rubin Reference Feeley and Rubin2000). In turn, legislative and executive actors made “extensive use of litigation to pursue policy” and overcome the constraints of a fragmented policy-making system (Barnes Reference Barnes2019, 148). Congress incentivized interest-group litigation and private enforcement to side step the executive branch (Farhang Reference Farhang2010). And party leaders and presidents supported courts intervening in controversies to shift blame or evade legislative obstructions to their agenda (Graber Reference Graber1993; Whittington Reference Whittington2005).

In short, existing scholarship views shadow effects through the prism of judicialization. American policy makers may situationally find themselves opposed to judicial review, but they have largely adapted to a judicialized environment and harnessed the shadow effect of courts for their policy-making advantage. To the extent that policy makers embrace preemptive reforms, it is to survive an almost inevitable tide of litigation and to influence judicial decisions rather than to undermine judicial review. The conjunction of interest-group litigation and political deference to (or outright support for) judicial policy making makes for “permissive conditions” (Soifer Reference Soifer2012, 1574) highly favorable for shadow effects. However, the resulting insights may not travel to many other polities where some or all attributes of adversarial legalism are lacking (Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2020, 478). For instance, international courts oftentimes struggle to build their case law (Alter Reference Alter2014, 108) and are regularly plagued by government efforts to resist their authority or contain their rulings (Conant Reference Conant2002; Martinsen et al. Reference Martinsen, Blauberger, Heindlmaier and Thierry2019; Voeten Reference Voeten2020). Moreover, in civil law and corporatist states bureaucratic modes of interest intermediation and political opposition to adversarial legalism can significantly constrain litigation and judicial review (Hofmann and Naurin Reference Hofmann and Naurin2021; Kagan Reference Kagan1997; Kelemen Reference Kelemen2011; Merryman and Perez-Perdomo Reference Merryman and Perez-Perdomo2007; Pavone Reference Pavone2018).

Does the absence of sustained litigation and political support for judicial policy making constitute a scope condition for the shadow effect of courts? What of courts struggling with limited opportunities to establish precedents and political elites ready to resist judicial policy making? Contrary to existing expectations, we argue that courts can prompt preemptive reforms even in these more hostile political contexts. Yet, to theorize this possibility we cannot view shadow effects through the prism of judicialization. Instead, we must view shadow effects as the outcome of a politics of resistance to judicial authority,Footnote 1 with profoundly different implications for the fate of judicial policy making.

To wit, in countries where political elites neither support nor regularly expect judicial interference, public policies may significantly eschew legal obligations and deviate from how judges would interpret the law. So long as noncompliance is not detected, policy makers can adopt favored policies without procuring courts with an opportunity to exercise oversight. Simultaneously, inviting a court to exercise judicial review and expose noncompliance can become a powerful latent threat. What if interest groups fail to mobilize this threat? Contrary to studies suggesting that the prospect of adjudication would evaporate (Blauberger Reference Blauberger2014; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008, 304), we argue that it is hardly eliminated: Bureaucratic conflicts that are potentially justiciable by courts provide an alternative trigger. While bureaucrats feature in existing impact studies (Epp Reference Epp2010; Feeley and Rubin Reference Feeley and Rubin2000; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008), the presumption remains that they act under pressure from (or in coordination with) outside litigants. Yet internal conflicts can push disaffected officials to turn to the courts without any outside litigation pressure. While bureaucratic conflicts may be more likely in federal polities (Bednar Reference Bednar2011, 281–2), even unitary states seldom behave as a “single, centrally motivated actor” (Migdal Reference Migdal2001, 22). Rather, they usually resemble a “heap of loosely connected parts or fragments” (Migdal Reference Migdal2001, 22) wherein “desires to maintain the status quo co-exist within the same persons with desires for change” (Berger Reference Berger2009, 397). Bureaucratic conflicts may thus emerge vertically between low-level officials and their superiors or horizontally between public agencies or political appointees and career professionals (Christensen Reference Christensen1991; Rosenthal, Hart, and Kousmin Reference Rosenthal, Hart and Kousmin1991). When these tensions arise, disaffected officials may threaten to solicit a court and expose noncompliance to bolster their institutional standing and policy-making discretion. In turn, policy makers previously opposed to reform may placate these officials to avert the outcome they most want to avoid: Providing courts with opportunities to exercise oversight, build their case law, and legitimate judicial review.

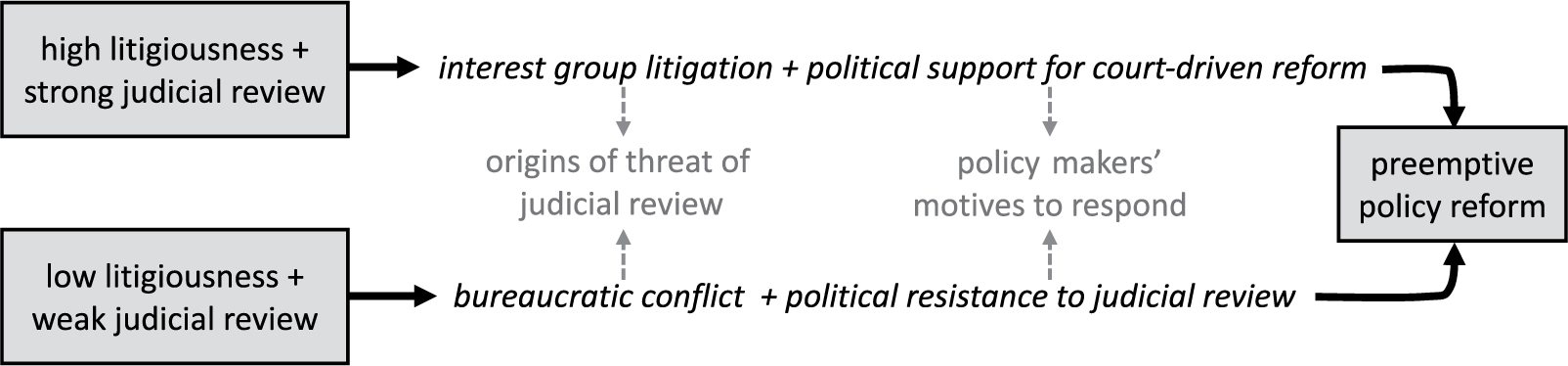

This alternative pathway breaks from existing research in two primary ways. First, with respect to process our theory does not rely on the comparatively exigent permissive conditions suggested by US judicial politics research. Even courts lacking a steady case load and political support for judicial review can prompt preemptive reforms if bureaucratic actors can substitute for interest-group litigants and policy makers are determined to obstruct judicial oversight. Neither do public officials have to be normatively invested in reform campaigns (Epp Reference Epp2010, 3; Feeley and Rubin Reference Feeley and Rubin2000, 61) to wield the threat of judicial review. While these motives may play a role, it suffices that they be sufficiently dissatisfied with the bureaucratic status quo that threatening to solicit a court becomes an expedient means to gain institutional and policy-making leverage. Finally, politicians who concede preemptive reforms need not do so out of deference or because they believe that judicial review advances their policy interests (Farhang Reference Farhang2010; Whittington Reference Whittington2005). They can also be driven by the opposite goal: to resist the institution of judicial review and quash opportunities for a judicialized mode of governance to take root. Figure 1 contrasts this alternative pathway with existing accounts. We detail both pathways in the next section.

Figure 1. Alternative Pathways for the Shadow Effect of Courts

Second, the consequences for judicial policy making differ markedly between the two pathways. In litigious settings where courts are swamped by lawsuits, judges may welcome and invite anticipatory reforms (Feeley and Rubin Reference Feeley and Rubin2000, 75, 101)—shadow effects complement judicial review. Conversely, in contexts where courts struggle to build their case law, preemptive reforms can starve judges of the opportunities needed to establish their policy making authority (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2019, 327–40)—shadow effects substitute for judicial review. In polities characterized by adversarial legalism, policy makers adopting preemptive reforms accept or embrace judicial review as a policy-making tool (Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2020; Epp Reference Epp2010; Melnick Reference Melnick1983)—shadow effects become part of judicialized governance. In less judicialized settings, policy makers can weaponize preemptive reforms to undermine judicial review and contain litigation—shadow effects become part of political resistances to adversarial legalism (Kagan Reference Kagan1997).

This insight illuminates how the shadow effect of courts can result from the same defiant politics that comparativists and international relations scholars have hitherto tied to backlash against courts (Madsen, Cebulak, and Weibusch Reference Madsen, Cebulak and Weibusch2018; Voeten Reference Voeten2020) and efforts to restrict compliance with their judgments (Conant Reference Conant2002; Martinsen et al. Reference Martinsen, Blauberger, Heindlmaier and Thierry2019). Recalcitrant policy makers may find conceding preemptive reforms a reasonable price to avoid the undesired consequences of backlash and noncompliance. As Blauberger (Reference Blauberger2014, 460) argues, noncompliance with courts is “vulnerable to follow-up challenges and, thus, invite[s] ever more judicial interference in domestic affairs.” Adverse rulings, even if contested, enable judges to set precedents that can inspire more litigation (Blauberger and Schmidt Reference Blauberger and Schmidt2017; Cichowski Reference Cichowski2007; Kagan Reference Kagan2019, 171; Silverstein Reference Silverstein2009), and they can also cultivate the public perception that policy makers require judicial oversight, a “worst case scenario” (Blauberger Reference Blauberger2014, 461–2) for public officials unaccustomed to being constrained by courts. Even if preemptive reforms risk exposing past noncompliance, they enable policy makers to cultivate the perception that they can detect and reform problematic policies on their own. They can also mitigate unwanted foreign scrutiny for states embedded in international organizations capable of monitoring, shaming, and sanctioning noncompliance or backlash to courts (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002).

In short, while courts can bear preemptive policy influence even in nonligitious and judicialized settings, it may hardly be the influence that judges want or need. For in placating disaffected officials via anticipatory reforms, policy makers can starve courts of the cases necessary to build their authority in a way that is difficult to detect.

Tracing Shadow Effects: Case Selection and Methods

To empirically assess our theory of the shadow effect of courts, we deploy process-tracing methods in a carefully selected and contextualized case study.

Our case selection strategy is to identify a case for “theory-testing process tracing” (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2018; Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 97, 160) in which both the threat of judicial review (the theorized cause) and a preemptive policy reform (the outcome of interest) are observed where we would not expect shadow effects given existing research. Because we wish to assess whether an alternative mechanism (bureaucratic conflict and political resistance to judicial review) can trigger these effects, we draw from a population of cases with a divergent set of contextual conditions (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 144): cases where interest-group litigation is rare and political elites oppose judicial policy making. In these more hostile political settings for courts, it is less likely that policy reforms triggered by the anticipation of adjudication would emerge from the same sequence of events and activities as in judicialized settings, given that the mechanisms underlying causal processes are context-bound (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2018; Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 322; Falleti and Lynch Reference Falleti and Lynch2009). By demonstrating a politics of preemptive reform in a hard case beyond the scope of existing theories, we show that shadow effects may be more ubiquitous than is presumed, albeit with profoundly different implications for judicial policy making and comparative research on judicial impact.

To this end, we probe what Hirschl (Reference Hirschl2011, 449) calls a “largely unexplored paradise” for the study of judicial politics: The Nordic states. While the Nordic countries top crossnational rule of law and judicial independence indices (Linzer and Staton Reference Linzer and Staton2015), they are also prototypical polities that have resisted the spread of adversarial legalism and “American-style high-voltage constitutionalism” (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2011, 450; Kagan Reference Kagan1997). First, the Nordic countries lack a tradition of strong judicial review (Lijphart Reference Lijphart1999, 225–8; Wind Reference Wind2010, 1039) and the constitutional courts that tend to serve as motors of judicial policy making outside of the US (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2004; Stone Sweet Reference Stone Sweet2000; Reference Stone Sweet2002). Second, compared with other European democracies, the Nordic states are more hostile to the authority of international courts and the constraints stemming from international law (Wind Reference Wind2010) in the view that they would “erod[e] representative democracy” (Selle and Østerud Reference Selle and Østerud2006). Third, the Nordic countries are exemplary unitary corporatist states that adopt a “consensus-seeking approach” of interest-group intermediation that “frequently resolve[s] conflicts without the use of the courts” (Sverdrup Reference Sverdrup2004, 21–8). Finally, the Nordic countries are characterized by a comparatively high levels of public trust in the state, affording wide scope for “active and interventionist” policy making with minimal judicial oversight (Selle and Østerud Reference Selle and Østerud2006, 551). Indeed, critics malign that “in the Scandinavian countries, there is too much trust in, and too much dependence upon, state bureaucracy, while, at the same time, too few checks and balances limiting the scope of state power” (Selle and Østerud Reference Selle and Østerud2006, 551–2).

Within this population of comparatively nonlitigious and nonjudicialized cases, we focus on a particularly improbable politics of judicial impact centered on a little-known international court—the EFTA Court—unfolding within Norway, the largest state under the Court’s jurisdiction. Compared with other European courts, the EFTA Court has been wholly neglected by political scientists, and for seemingly good reasons: The Court appears not only contextually ill-positioned but also institutionally ill-equipped to have much policy-making influence—let alone without being solicited! The EFTA Court is relatively new and has a limited case load, renders mostly advisory rather than binding rulings,Footnote 2 lacks direct access for private litigants, and in a ranking of 24 international courts’ formal independence it occupies the middling 14th spot (Alter Reference Alter2014; Squatrito Reference Squatrito2020). The EFTA Court thus better approximates the limited power of most international courts than its more-studied European counterparts (Staton and Moore Reference Staton and Moore2011). Furthermore, Norway has a long-standing history of political resistance to the EFTA Court and its capacity to interpret European law (Fredriksen Reference Fredriksen, Howse, Ruiz-Fabri, Ulfstein and Zang2018). According to the EFTA Court’s recently retired President, “Oslo bureaucrats … got into the habit of systematically denigrating the EEA [European Economic Area] agreement and … in particular, the EFTA Court [which was] seen as a threat to Norwegian sovereignty and to the traditional social model.” Thus government officials would routinely “close ranks” when “defending the ‘Norwegian model,’ even against clear international law obligations” (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2019, 329–32).

The tendency to close ranks was placed in sharp relief as the Norwegian Labor and Welfare Administration (NAV)—an agency within the Ministry of Labor—denied thousands individuals their free movement and social-benefit rights under European law—including by prosecuting dozens for welfare fraud. Then after more than a decade of noncompliance, in 2019 the Norwegian government suddenly announced that this restrictive welfare policy would be immediately reformed, that prosecutions would cease, and that victims would be compensated. This announcement was followed by an internal NAV audit, a government-appointed inquiry, and the release of a large corpus of archival documents. By scouting this rich paper trail, we reconstruct how Norway’s welfare reforms arose in a campaign by top government officials to preclude a bureaucratic conflict within the Ministry of Labor from providing the EFTA Court with an opportunity to build its case law and legitimate judicial oversight.

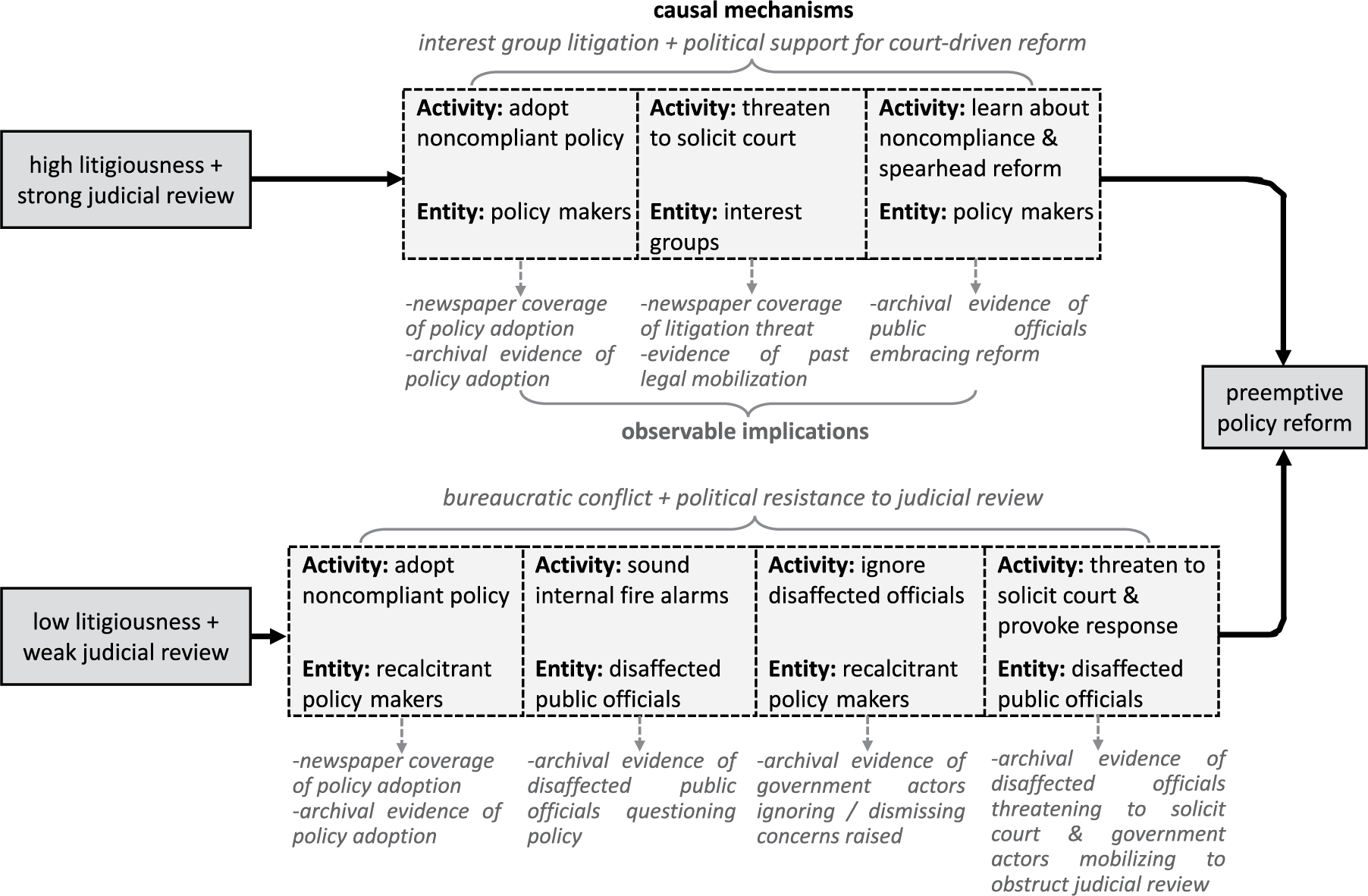

In particular, we adopt a mechanistic approach to process-tracing that crystallizes an “emerging understanding of [causal] mechanisms” as a “system that produces an outcome through the interaction of a series of parts of the mechanism” (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 39; Bennett, Fairfield, and Soifer Reference Bennett, Fairfield and Soifer2019, 11).Footnote 3 We follow Beach and Pedersen (Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 99–100) who conceive mechanisms as entities engaging in activities that generate observable traces in the empirical record concerning the chronology of events (sequence evidence) and the existence and content of hypothesized activities (trace and account evidence). To this end, Figure 2 sorts the alternative mechanisms summarized in Figure 1 into more detailed sequences of entities engaging in activities. First, we make explicit the common mechanism and chronology of events that tend to underlie existing studies focused on a litigious and judicialized setting like the US (the upper pathway). We then proceed likewise for our theory of how bureaucratic conflict and political resistance to judicial review can trigger preemptive reforms in less judicialized contexts (the lower pathway).

Figure 2. Sorting Shadow Effects into Entities, Activities, and Observable Implications

Figure 2 includes examples of the types of evidence that can corroborate each part of the pathway(s).Footnote 4 A primary advantage of the archival materials available to us is that they include unusually detailed chronologies of correspondence from public officials with discretion to change government policy who did not expect their communications to be made public, which bolsters the evidence’s credibility and increases our capacity to evaluate precise predictions (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 104–6). Specifically, we adopt a Bayesian inferential logic wherein we assess whether the archival evidence increases confidence in one mechanism being at work relative to its alternative(s) (Fairfield and Charman Reference Fairfield and Charman2019, 158). The probative value of evidence grows the more it helps us evaluate “certain predictions” about evidence that must be observed for a mechanism to be present and “unique predictions” concerning empirics tied to only one theorized mechanism (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2019, 96–102; Bennett, Fairfield, and Soifer Reference Bennett, Fairfield and Soifer2019, 3; Van Evera Reference Van Evera1997). For example, uncovering a letter by an advocacy group threatening to sue the NAV would increase confidence in existing theories, whereas government correspondence evidencing disaffected public officials threatening to trigger judicial review in the absence of litigation pressure would increase confidence in our alternative account. Finally, to evaluate whether reforms attenuating noncompliance denote the shadow effects of courts rather than reactive responses to new legal information (as in managerial accounts of compliance; see Table 1), we focus on sequence evidence impinging on the Norwegian government’s public claims that it speedily changed policy as soon as policy makers became aware of noncompliance.

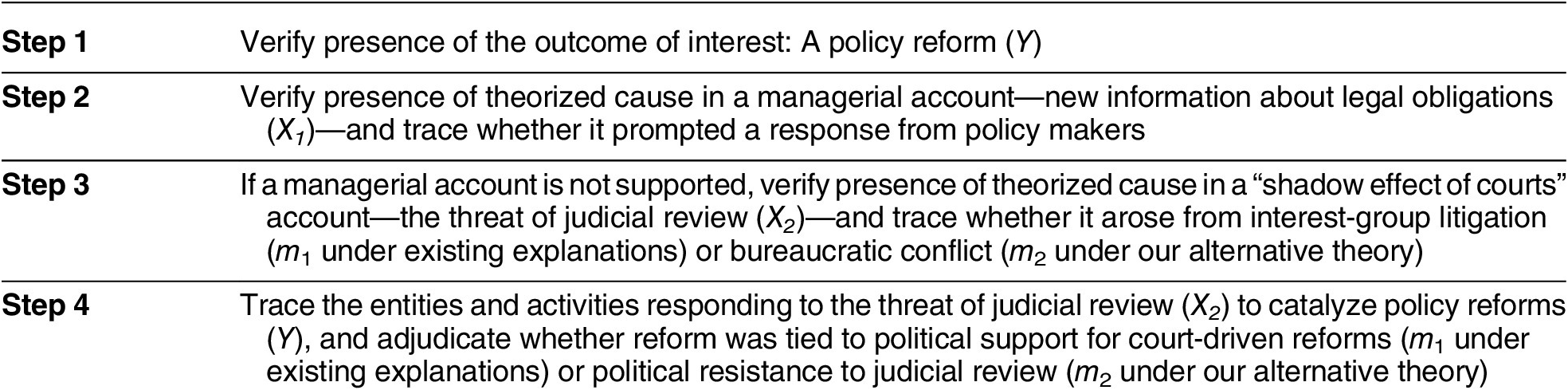

Our procedure for process tracing follows the four steps that are summarized in Table 2. As in most case-based research, we begin with the outcome of interest Y (Norway’s welfare-policy reform), work our way backward to corroborate the presence of the theorized cause X, and then trace the mechanism m—the relevant entities and activities—that linked the cause to the observed outcome. Because these inferences constitute contestable evidentiary claims, we follow Moravcsik (Reference Moravcsik2014) and compile our sources in a transparency appendix (TRAX) that can be consulted to assess our analysis (Pavone and Stiansen Reference Pavone and Stiansen2021).

Table 2. Procedure for Tracing the Shadow Effect of Courts

Preemptive Reform in the Shadow of the EFTA Court

The Outcome: A Sudden Reform after Years of Noncompliance

Our theory-testing case study begins with a 2019 welfare-policy reform in Norway following more than a decade of noncompliance with European law. The reform shook Norway’s political landscape, yet at first glance it hardly appeared to be a preemptive act that was sparked by the threat of judicial review.

Although Norway is not a member of the European Union (EU), it is nonetheless bound by European law. As an EFTA member state, Norway, as well as Iceland and Lichtenstein, has ratified the 1994 European Economic Area (EEA) Agreement that renders it part of the European common market and binds it to EU rules protecting the free movement of persons, goods, services, and capital. EU regulations are continuously incorporated into the EEA agreement and are supposed to be speedily transposed into domestic law. Where conflicts between EEA rules and domestic law arise, EEA rules and the EFTA Court’s interpretation of these rules prevail—at least on paper.

Yet, as is often the case in legal orders lacking strong enforcement mechanisms, “rules that exist on paper [may be] widely circumvented and ignored” (Helmke and Levitsky Reference Helmke and Levitsky2004, 727). This political dynamic is particularly evident when it comes to EEA rules protecting the so-called exports of social benefits. Norway’s ability to restrict social-benefit exports has been progressively constrained by EU rules—specifically by EU Regulation No. 1408/71 (pre-2012) and then by EU Regulation No. 883/2004 (post-2012), seeking to coordinate social-security systems within the European common market. Crucially, these regulations prohibit discrimination in allocating social benefits based on beneficiaries’ country of residence or their choice to travel or relocate to another EEA country, thus tying beneficiaries’ welfare rights to their free-movement rights (Arnesen et al. Reference Arnesen, Fløistad, Strandbakken, Jendal, Midthjell, Sanderud and Wærnes2020).

Despite these international obligations, the Norwegian government enacted and enforced policies severely curtailing social benefits to individuals traveling abroad. For instance, in 2006 legislation was amended to explicitly state that “[i]t is a condition of entitlement to sick pay that the beneficiary resides in Norway” (TRAX, A.1). A subsequent circulaire to NAV bureaucrats—the civil servants charged with implementing the law and processing social-benefits cases—specified that they should use their discretion to identify whether EEA rules should prevail over established practice. Even upon EU Regulation No. 883/2004’s incorporation into the EEA agreement in 2012, the Norwegian government communicated both to Parliament (TRAX, A.2) and to the relevant bureaucracies (TRAX, A.3) that it did not believe that important changes to Norwegian law or practices were required. In fact, when in 2013 Ministry of Labor bureaucrats proposed relaxing the requirement that beneficiaries secure NAV approval before traveling, the Ministry’s political leadership blocked cabinet-level consideration of the proposal (TRAX, A.35).

These restrictive policies crystallized an increasingly salient objective across successive governments coinciding with growing antimigration sentiment across Europe, mobilized with particular zeal in Norway by the ascendant right-wing Progress Party. Calls to prevent the exploitation of Norway’s generous welfare state became frequent. For instance, a government white paper stated that

with the rise in labour immigration to Norway and the increased mobility of people between Norway and other EEA countries, the proportion of benefits that are exported is growing. The possibility that benefits will be exported is assessed when the various schemes are developed. The Government is monitoring the situation closely to ensure that benefit schemes are not abused. (TRAX, A.31)

In seeking to stem these supposed “abuses,” Norwegian policy makers acknowledged that their discretion was formally limited by EEA rules. Another white paper cited how the new 2012 EU Regulation “restrict[s] the scope for action to regulate immigrants’ and emigrants’ access to, and opportunities to bring social-security benefits to other countries”(TRAX, A.4). In turn, EEA free-movement rules became a growing target of political criticism. In 2012, Siv Jensen, the leader of the Progress Party, told journalists that “[w]e are for work immigration, but against welfare refugees. Therefore, we have to set restrictions. If we encounter obstacles in the EEA system, we will have to challenge them” (TRAX, A.5). When the Progress Party became part of the governing coalition the following year, the government announced that it would “[c]onsider measures that will limit and bring to a halt the export of social-security benefits” (TRAX, A.32).

As travel restrictions for welfare beneficiaries continued to be applied by NAV bureaucrats and law enforcement into 2019, even short-term and necessary travels without prior authorization became prohibited. As a result, at least 2,400 individual cases were wrongly assessed in violation of EEA rules, resulting in the loss of cash benefits, at least 78 individuals who undertook long or repeated stays abroad were convicted for social-security fraud, and 48 individuals were wrongfully jailed (TRAX, A.33). One resident of Norway since 1982 who was slapped with a two-month jail sentence and deportation notice for visiting his ailing mother in Greece would later tell the press that “this case has ruined my life”(TRAX, A.34).

Then suddenly, after at least a decade—and possibly up to 25 years—of noncompliance with EEA obligations (TRAX, A.33), the Norwegian government abruptly balked. On October 28, 2019, the Minister of Labor, Anniken Hauglie, requested to be summoned to Parliament to account for the application of EU Regulation No. 883/2004 (TRAX, A.30). Flanked by the NAV Director and the Director of Public Prosecutions, Hauglie then held a press conference admitting that Norway had for years violated its EEA obligations by barring social-benefit recipients from traveling abroad (TRAX, A.33). The NAV had thus reformed its practice and individuals who had been unlawfully prosecuted, imprisoned, or denied their cash benefits would have their cases reopened and be compensated accordingly.

The October 28 press conference triggered a political firestorm. Norwegian newspapers described the government’s admission as an “unprecedented scandal” and “the biggest welfare scandal of all time,” running front-page stories featuring victim interviews and headlines like “I was viewed as a criminal” (TRAX A.34). To counter public criticism, government officials repeatedly invoked a benign account of noncompliance consistent with managerial theories of compliance. Claiming that “Norway is generally far ahead in terms of loyal adherence to EU/EEA law,” Norway’s Attorney General tied noncompliance to a “lack of awareness and investigation” (TRAX, A.29). The NAV Director echoed this sentiment, claiming that noncompliance was due to “a collective misinterpretation” of EEA law (TRAX A.34), as did the Director of Public Prosecutions, who lamented that “if we’d been notified earlier” about relevant EEA provisions, “we would have investigated thoroughly”(TRAX A.34). In this account, insufficient knowledge was the root of noncompliance, yet the government demonstrated its capacity to reform problematic policies and its willingness to bolster awareness of EEA law.

Rather tellingly, public officials’ damage-control efforts did not elaborate on the sudden timing of reforms. Thankfully, a trove of archival evidence released to the public allows us to identify when policy makers became aware of noncompliance, how they failed to act upon this knowledge, and how they reacted differently to an event conspicuously absent from the government’s press statements: a mounting conflict between the NAV and an administrative appeals board within the Ministry of Labor that threatened to trigger adjudication by the EFTA Court.

The (Non)Cause: How Evidence of Noncompliance Was Ignored

To identify what triggered Norway’s policy reforms, we first assess the explanatory purchase of existing managerial theories of compliance favored by the Norwegian government itself: were government officials unaware of their EEA obligations, and did they speedily enact reforms once they received evidence of noncompliance (the theorized cause, X 1, in managerial accounts; see Table 2)? To this end, we gather evidence that sequentially captures how policy makers responded to a series of events where they were alerted to the conflict between Norwegian and European law. By tracing not just what happened but when it happened (Pierson Reference Pierson2000), we cast significant doubt on managerial explanations and demonstrate that policy makers’ behavior belied both awareness of noncompliance and recalcitrant policy preferences.

We have already noted that by 2013, government-coalition leaders expressed a desire to “challenge” any EEA rules (TRAX, A.5) that constrained their capacity to “halt the export of social-security benefits” (TRAX, A.32). Even when policy was eventually reformed in 2019, the Minister of Labor expressed concerns that they would lead to increased social-security exports and called for other mitigating measures to be implemented (TRAX, A.24). In light of these policy preferences, it is unsurprising that mounting evidence of noncompliant practices was repeatedly ignored, dismissed, and even suppressed within the Ministry of Labor. As early as 2009, the NAV’s own audit revealed that the agency’s Directorate expressed doubts about whether restrictions on welfare “exports” conflicted with beneficiaries’ EEA free-movement rights. Nevertheless, the Ministry of Labor reiterated that “as a general rule, there should be a condition for the right to [cash benefits] that the person resides in Norway” (TRAX, A.6). Then in 2014 and 2015, NAV street-level bureaucrats voiced concerns that the agency’s application of domestic law violated EEA rules on an internal online discussion board (TRAX, A.10). On two occasions these concerns were not addressed by their superiors, and in a third they were rebutted by recapitulating existing policy (TRAX, A.10).

Simultaneously in 2015, an individual lodged a complaint to the EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) after the NAV denied his request to relocate to Sweden while continuing to receive Norwegian social benefits. In response, the ESA requested that the Norwegian government provide information and discuss its allegedly restrictive policy, underscoring that under EU Regulation No. 883/2004 “neither the acquisition, nor the retention of the benefit may be denied on the sole ground that the person concerned resides in another Member State” (TRAX A.23). The NAV and the Ministry of Labor corresponded in preparation for these meetings in 2016 and 2017, yet Norwegian officials presented inaccurate information about domestic practice to the ESA. The NAV’s audit concluded that NAV representatives in these meetings were aware of the inaccuracies but did not believe that it was their responsibility to correct the record (TRAX, A.11). After being supplied incorrect information, the ESA chose not to pursue the matter further.

By 2017, the Ministry of Labor was hardly the only government agency that had received clear internal signals that its restrictive welfare policy contravened European law. In the same year, Norway intervened as a third party in a European Court of Justice case concerning validity of UK legislation very similar to the NAV’s restrictive social-benefits policy. UK law required residency in Great Britain for individuals to receive disability living allowances, and rather tellingly, lawyers from Norway’s Attorney General’s office intervened “largely [in] support [of] the British authorities” (TRAX, A.33). These efforts proved unsuccessful, as the European Court unequivocally rebutted in its Tolley ruling that EU law

must be interpreted as preventing legislation of the competent State from making entitlement to an allowance such as that at issue in the main proceedings subject to a condition as to residence and presence on the territory of that Member State.Footnote 5

The Norwegian government was immediately notified of the ECJ’s adverse judgment. Although the legal advice that the Attorney General’s office subsequently supplied the government has not been made public, it is very unlikely that the Attorney General and other high-level officials did not recognize that the Tolley judgment impinged directly on the legality of NAV’s restrictive benefits policy.

The foregoing evidence is not exhaustive. In the following sections we will highlight additional materials corroborating the inference that growing awareness of noncompliance failed to persuade Norwegian officials to change course. Thus even if Norway’s initial noncompliance could be partially attributed to insufficient legal knowledge consistent with managerial theories, this explanation cannot account for why reforms were not enacted well before 2019 once information became abundant.

The Cause: A Bureaucratic Conflict, a Threat of Judicial Review

The lone citizen complaint lodged with the ESA in 2015 puts in sharp relief how Norwegian advocacy associations had failed to organize prospective litigants and serve as “fire alarms” of noncompliance (McCubbins and Schwartz Reference McCubbins and Schwartz1984). We uncovered no archival evidence that Ministry of Labor officials worried or were aware of a coordinated litigation campaign targeting the restrictive social-benefits policy, nor did we identify media reports suggesting the existence of such efforts. Yet despite the absence of interest-group litigation (m 1 in Table 2), the NAV did suddenly face a threat of judicial review (the cause, X 2, in “shadow effect of courts” accounts; see Table 2) arising via an alternative mechanism: the escalating tensions between the agency and the Ministry of Labor’s quasi-judicial appeals body—the National Insurance Court (NIC; m 2 in Table 2).

The NIC is an appeals body for disputes concerning the NAV’s allocation of social-security and pension benefits. Although the NIC operates under the auspices of the Ministry of Labor, is not part of Norway’s ordinary court system, and does not formally have a “case law,” it describes itself as an independent administrative body with “court-like” functions that “cannot be instructed by any political or other organisation.”Footnote 6 It was in great part the NIC’s liminal institutional status that became the source of bureaucratic conflict: Beginning in 2017, the NIC issued a series of ever-clearer decisions against the NAV citing EEA law, and it interpreted these decisions to be binding rulings by an independent authority. Conversely, the NAV ignored these decisions and treated the NIC as a dependent advisory body within the executive branch, causing the NIC’s frustrated members to seek new ways of gaining leverage over their recalcitrant interlocutors.

In the summer of 2017, two lawyers with expertise in EEA law became members of the NIC—one of whom had previously served in the ESA legal affairs department (TRAX, A.33). The NIC thus grew increasingly skeptical that national restrictions on social-benefit exports complied with beneficiaries’ free-movement rights under EEA law. Initially, the NIC signaled this skepticism by prodding the NAV to take beneficiaries’ EEA rights more seriously. The first of these decisions were delivered on June 12th and 16th, 2017, wherein the NIC held that because the NAV had not “assessed the case complex in accordance with the EEA agreement” (TRAX A.25) nor

made any assessment of article 21 [of EU Regulation No. 883/2004] … the court finds it appropriate to revoke the appealed decision so that [the beneficiary’s] claim for sickness benefit can be assessed against article 21. The court would note that Article 21, in its wording, applies not only in cases where the member lives in a Member State other than the competent State, but also in cases where the member temporarily resides in another Member State. (TRAX, A.7)

In the subsequent months, the NIC rendered at least nine similar rulings (Internrevisjonen 2019, 41–2). In addition to citing the relevant EEA rules, several of these decisions cited the ECJ’s Tolley judgment and explicitly held that the NAV was failing to take EEA law into account. Yet the NAV chose to “si[t] on this information” (TRAX, A.33) and continue to deny travel requests by social-benefit recipients and file criminal charges against some beneficiaries. The NAV’s internal audit confirms that the NIC’s decisions were debated, but practices were not changed, at least in part, because some officials disagreed with the rulings (TRAX, A.8). In response, the NIC issued even more pointed decisions admonishing the NAV. In August 2018, the NIC held that not only had the NAV failed to take EEA law into account but that its entire policy restricting social-benefit “exports” directly conflicted with EEA law. Strikingly, the NAV again refused to alter its disposition even in the case that had triggered the NIC’s latest rebuke (TRAX, A.9). As a result, frustration within the NIC intensified. The NIC’s President later testified before the Norwegian Parliament that the NIC’s “legal understanding must have been known before these cases were sent to us. So in the fall of 2018, it was clear to us that the NAV did not [intend to] comply with the NIC’s interpretation of the law” (TRAX, A.9).

Beyond the NAV’s defiant stance, the testimony of the NIC’s President suggests that two factors aggravated the conflict with the NAV. First, the NAV’s litigation strategy was leaving judges (and the public) in the dark. The NAV did not appeal any of the NIC’s adverse decisions within Norway’s ordinary court system, which would have been the normal procedure if the NAV believed that the NIC misinterpreted the law (TRAX, A.9). By ignoring rather than appealing the NIC’s rulings, the NAV ensured that awareness of its dispute with the NIC was contained within the Ministry of Labor. Indeed, even experts on the NIC and Norwegian social policy acknowledged that they were unaware of cases challenging the legality of domestic restrictions on social-benefit “exports” (Lundevall Reference Lundevall2017, 161).

Second, the NAV’s defiance belied a deeper disagreement within the Norwegian state concerning the institutional autonomy of the NIC. The NAV’s behavior was ensconced in a view of the NIC as an advisory and subservient agency in the executive chain of command. Conversely, the NIC’s adverse decisions conveyed its members’ self-conception as quasi-judicial actors with independent authority. These conflicting views were placed in sharp relief during the NIC President’s parliamentary testimony:

Member of Parliament [MP] 1: “Did the NIC at any time contact the Ministry [of Labor] about these issues?”

NIC President: “The NIC issues individual rulings and we hand them to the parties … it is NAV that has the contact with the Ministry about what will happen next. We do not notify the Ministry or the [NAV] Directorate.”

MP 2: “Did you then consider that this fact was a matter that you should inform upward about?”

NIC President: “No. I did not do that… . It is not going to happen. That is, the Ministry is informed by the Directorate.”

MP 3: “You said that you did not inform the Ministry. You are an underlying agency in relation to the Ministry, as I perceive it.”

NIC President: “We are an underlying agency, but we are independent. And we issue rulings and rulings in line with a court. And it is not in the system that we have to notify the Ministry.” (TRAX A.26)

Internal correspondence between the NAV’s Directorate and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirms that the NAV shared Parliamentarians’ view of the NIC as a dependent administrative agency, in contrast to the NIC President’s characterization of her institution as a court-like body (TRAX A.16). We specify this evidence further in the next section.

Faced with an increasingly intractable bureaucratic conflict and the evident failure of a managerial logic of compliance, the NIC decided to change tact. On November 19, 2018, the NIC threatened to trigger judicial review. Although under Norwegian law only the NAV could trigger review by a domestic court via a motion for appeal, under the EEA Agreement the NIC could directly solicit the EFTA Court by requesting a preliminary ruling over the domestic application of EEA law. The NIC thus sent the NAV a letter making it clear that it was seriously considering to ask the EFTA Court to pass judgment over the validity of Norway’s social-benefits policy. The letter stated that “in a number of decisions” the NIC held that beneficiaries’ EEA free-movement rights prevailed over domestic rules requiring Norwegian residency, yet “neither the NAV nor the NAV Appeals Authority appear to have adopted this practice.” Thus the NIC

is considering to refer the question of whether EEA Regulation 883/2004 also includes short-term stays in EEA countries to the EFTA Court. In this case, an advisory opinion will be requested from the Court … [so] that this question is clarified.” (TRAX, A.12)

The NAV’s immediate reaction to this threat of judicial review proved in sharp contrast to its habit of ignoring the NIC’s attempts to remind the agency of its EEA obligations.

The Mechanism: Preemptive Reform as a Politics of Resistance

For 10 years, the NAV disregarded mounting evidence of noncompliance. Yet in the span of just a couple of weeks, the NIC’s letter prompted a sudden interagency frenzy to thwart judicial review by the EFTA Court consistent with our theorized mechanism, m 2, undergirding the “shadow effect of courts” in less judicialized contexts (see Table 2). The letter was forwarded to the NAV’s Directorate on November 27th, which immediately notified the Ministry of Labor (TRAX, A.13). A few days later on December 7th, the NAV received yet another letter from the NIC conveying that it was considering referring a second case to the EFTA Court. The NAV alerted the Ministry of Labor concerning the second letter on December 11th and urgently reminded the Ministry that it needed an opinion on the matter (TRAX, A.14). In the meantime, the NAV secured a deferred deadline of January 31, 2019, for submitting observations to the NIC.

This rush of internal deliberations corresponded with an abrupt suspension of the enforcement of social-benefits restrictions. On December 18th, the NAV ceased processing all complaints concerning social-benefits “exports” to EEA countries (TRAX, A.15). Two days later it sent yet another letter to the Ministry of Labor stressing the growing likelihood of referrals to the EFTA Court and underscoring that complying with the NIC’s interpretations of EEA law implied a “significant change in policy.” The NAV concluded the letter by asking to be summoned for an interagency meeting to coordinate an appropriate response “well in advance of the deadline of January 31” (TRAX, A.14). To date, we lack direct evidence concerning discussions of these letters among Ministry of Labor officials. The Ministry took the NAV’s calls seriously and arranged a meeting on January 18, 2019, but in a deviation from standard procedures no minutes exist from the meeting (Internrevisjonen 2019, 48).

Simultaneously, the NAV scouted for any feasible way to block the NIC from soliciting the EFTA Court. In an e-mail the NAV sent the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on January 16, 2019, the NAV queried whether it could argue that the NIC lacked jurisdiction to refer a case to the EFTA Court, as it is “an administrative body” rather than an ordinary court (TRAX, A.16). This view channeled the NAV’s habit of not treating the NIC’s decisions as court-like precedents, as well as a broader government strategy of restricting the set of actors capable of soliciting the EFTA Court. According to the EFTA Court’s ex-president, it was long apparent that Norway’s “goal once again was to keep cases out of the Court,” so he and his colleagues adopted a “functional approach” to safeguard “broad access,” as they “did not want to lose a case” and be denied the ability to “further [the] development of the Court’s case law” (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2019, 100–1). The “Norwegian government [had since] made a big fuss” (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2019, 100) over the EFTA Court’s “broad and liberal” standing requirements (Butler Reference Butler2020, 324), and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs acknowledged as much in its reply to the NAV: The EFTA Court “had set the bar low” despite Norway arguing “against such an interpretation,” and it was all but certain to accept the NIC’s referral (TRAX, A.16). As a result, the NAV did not pursue a direct blocking strategy further.

What the NAV ultimately did propose was sufficient policy changes to appease the NIC and cajole it from soliciting the EFTA Court. In a letter to the Ministry of Labor on January 24th, the NAV recommended that “practice should be changed so that, to a greater extent than what has been the case so far, it is in accordance with the NIC’s view.” In arguing for preemptive reforms, the agency elaborated its motives and desire to avoid adjudication:

The NAV has no real opportunity to influence a possible decision by the NIC to submit the case to the EFTA Court. However, it is assumed that a change that brings the NAV’s practice closer to the NIC’s view will reduce the likelihood that the court will request an opinion from the EFTA Court. The Directorate therefore wishes to adapt future practice … instead of obtaining a decision from the EFTA Court. We consider that, by changing practices, the Norwegian authorities will have a greater opportunity to decide for themselves the importance of temporary stay abroad for the right to the benefits in question than if we receive a decision from the EFTA Court. (TRAX, A.17)

The significance of this letter is evident in light of Norway’s historical opposition to US-style judicial review (Hirschl Reference Hirschl2011; Selle and Østerud Reference Selle and Østerud2006) and its oftentimes recalcitrant relationship vis-a-vis the EFTA Court (Fredriksen Reference Fredriksen, Howse, Ruiz-Fabri, Ulfstein and Zang2018). Norwegian politicians had long accused the EFTA Court of acting “more Catholic than the Pope” in restricting Norway’s policy-making discretion under the EEA Agreement (Magnússon Reference Magnússon2011, 517), and their efforts to discipline the EFTA Courts’ judges by blocking their reappointments had prompted charges of Norway “meddling with judicial independence” (Fredriksen Reference Fredriksen, Howse, Ruiz-Fabri, Ulfstein and Zang2018, 143; Hirst Reference Hirst2017). The NAV’s belief that it would be preferable to adopt preemptively reforms over submitting to international adjudication tapped a well-known strategy of securing the government’s “room for maneuver” and “safeguar[d] national interests” by resisting the EFTA Court’s efforts to build a “very far reaching interpretation of the EEA agreement” (TRAX. A.29). The strategy so frustrated the EFTA Court’s ex-president that he penned a number of increasingly combative editorials in the Norwegian press and two books lambasting the “room for maneuver” policy (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2019; Reference Baudenbacher2021; TRAX, A.28).

Indeed, in advocating for preemptive reforms, the NAV proposed the minimal changes needed to placate the NIC while maintaining discretion to restrict social benefits. Unlike the progressive reformers that often drive preemptive policy making in the shadow of American courts (Epp Reference Epp2010; Feeley and Rubin Reference Feeley and Rubin2000), NAV officials advocating policy changes were hardly persuaded about the substantive merits of reform. Not only did their proposal fail to categorically renounce restrictions on social-benefit “exports;” it embraced reforms that would only affect future cases and avoid compensating individuals who had been unlawfully imprisoned or lost benefits. The letter limited the scope of reform to individuals undertaking short stays abroad, and officials did not deem it necessary to terminate criminal prosecutions already underway (Internrevisjonen 2019, 52–3). The desire to contain the reform’s scope was broadly shared. When the Ministry of Labor approved the NAV’s proposal via e-mail on February 22nd and in an official letter on March 5th, it stressed that the NAV should only reform its handling of future cases and continue to seek ways of limiting payments to beneficiaries living abroad (TRAX, A.18).

Shortly after receiving informal approval by the Ministry of Labor, the NAV responded to the NIC. In a letter to the NIC on February 26th, the NAV briefly stated that it would change those practices that the NIC had found objectionable (TRAX, A.19). Apparently satisfied, the NIC retracted its threat of soliciting the EFTA Court. To be sure, the NIC could have still referred the cases and enabled the EFTA Court to oversee the government’s reform efforts. Its choice to not do so suggests that the NIC’s objective was ultimately more pragmatic and institutional (to bolster its autonomy and influence vis-a-vis the NAV) than it was progressive and policy driven (to enable the EFTA Court to exercise oversight and interpret European law) (TRAX, A.27).

Yet, even after the NIC abandoned its threat of judicial review, policy makers soon recognized that their efforts to “contain justice” (Conant Reference Conant2002) and avoid public scrutiny were unsustainable. Initially, the NAV remained committed to minimal changes in practice (TRAX, A.21) and criminal prosecutions continued to be lodged through the summer of 2019, in part to avoid attracting media attention (Internrevisjonen 2019, 59). By August 2019, however, some NAV bureaucrats started questioning the feasibility of this approach. In an August 30th e-mail to the Ministry of Labor, NAV officials expressed concerns that in their experience “changes in practice [in future cases] lead to calls for reopening old cases” (TRAX, A.22). Eventually, government officials implemented reforms encompassing all stays in the EEA area, committing to reopening old cases and compensating victims. The archival evidence does not enable us to conclusively identify what motivated ramping up the reforms shortly before publicizing them, as the Attorney General’s advisory opinion that allegedly guided this decision remains confidential (TRAX, A.29).

What is clear is that publicizing a more comprehensive set of reforms was not without political benefits: Policy makers could more credibly claim to have detected and reformed a problematic policy without it becoming apparent that a court’s shadow had forced their hand. The NAV Director emphasized that her agency was “taking the initiative,” had “made thorough legal assessments” in response to the NIC’s decisions, and “changed the practice” (TRAX, A.20)—even though the NAV had defied the NIC for nearly two years. The Attorney General lauded the government’s efforts to “clarify EEA law in this field” (TRAX, A.29) because in conducting “lawsuits on various aspects of social security and the EEA, both before Norwegian and international courts” it had never become apparent “that there was an EEA breach” (TRAX, A.29)—even though his office’s lawyers intervened in the 2017 Tolley case concerning the illegitimacy of residency restrictions on benefits. And the Minister of Labor promised to spearhead an investigation to “get to the bottom of what has happened, and learn from it for the future” (TRAX A.34)—even though in 2017 the Ministry had persuaded the ESA to drop its investigation on the matter. No high-level government official admitted that what spurred them to begrudgingly act was the sudden threat of judicial review by the EFTA Court.

It is equally clear that the preemptive influence that the Norwegian government conceded the EFTA Court was hardly welcome from the Court’s perspective. “The EFTA Court has deliberately been prevented from exercising judicial oversight and giving guidelines for similar cases,” lambasted the Court’s retired President, who interpreted the NAV reforms as the latest exemplar of a “fierce endeavou[r] to keep cases out of the EFTA Court” (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2021, 55). Shadow effects may broaden the scope of indirect judicial influence and spur important policy reforms, but in more hostile contexts for judicial review they can also limit courts to a “shadow existence” (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2021, 125), forestalling the direct exercises of oversight through which courts establish themselves as authoritative policy makers.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that judges need not adjudicate cases to influence policy making, even in contexts where political resistance to judicial review is rife. The finding that seemingly dormant courts can still have a profound effect on politics and policy significantly broadens the scope of comparative research on judicial impact. Temporally, we should focus more efforts on understanding how the presence of courts influences the decisions of forward-looking policy makers even when litigation does not materialize. Geographically, we should pay greater attention to the oftentimes-fierce political struggles that preempt judicial impact, particularly in settings where courts’ political role may only appear marginal at first glance.

Our main conclusion is that the study of comparative politics and law is greatly enriched by grappling with the Janus-faced nature of the shadow effect of courts. Shadow effects can complement judicial review and bolster judicialization (Epp Reference Epp2010; Farhang Reference Farhang2010; Melnick Reference Melnick1983; Silverstein Reference Silverstein2009), but we have shown that preemptive reforms can also be weaponized to obstruct judicial review and forestall judicialization. By conceding some preemptive judicial influence in exchange for starving courts of politically salient cases, recalcitrant policy makers need not undermine formal judicial independence or wage the backlash and noncompliance campaigns that attract most scholarly attention (Abebe and Ginsburg Reference Abebe and Ginsburg2019; Madsen, Cebulak, and Weibusch Reference Madsen, Cebulak and Weibusch2018; Voeten Reference Voeten2020). Instead, they can cultivate the perception that judicial oversight is unnecessary, thereby evading the legalized accountability that is so central to judicialized governance (Barnes and Burke Reference Barnes and Burke2020; Epp Reference Epp2010; Kagan Reference Kagan2019). The appearance that courts do not matter in such contexts is thus less a reflection of reality and more a deliberate outcome of a politics of preemptive reform—a politics whose existence belies that courts can actually matter a great deal.

Indeed, even when shadow effects do not open the floodgates to judicialization, they remain a potential catalyst of policy and institutional change. First, where policy makers adopt preemptive reforms to preclude courts from exercising direct oversight, judges face growing incentives to compensate by expanding access to justice and maximizing their preemptive influence. For instance, the EFTA Court is one of 12 international courts that can only be solicited by bureaucratic actors if they exercise court-like functions (Alter Reference Alter2014). In response to the Norwegian government’s obstinance, the EFTA Court adopted a very encompassing interpretation of what constitutes a “court or tribunal” to cajole as many public agencies and bureaucrats as possible into wielding the threat of adjudication (Baudenbacher Reference Baudenbacher2019, 100). Legal scholars may lament these acrobatics (Butler Reference Butler2020) and they may not deliver the results that judges desire. But creating a more permissive “legal opportunity structure” (De Fazio Reference De Fazio2012; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2012) can convert policy makers’ hostility to judicial review into a productive force for policy change. For even in the absence of litigation, facilitating access to justice expands the shadow effect of courts and bolsters the capacity of reform advocates to hold policy makers accountable to their legal obligations.

Finally, even when preemptive reforms succeed in curbing judicial empowerment and styming interest group litigation, they may not succeed in precluding the shadow effect of courts from provoking important institutional changes within national bureaucracies. We have shown that when bureaucratic conflicts spur disaffected public officials to challenge the institutional status-quo by threatening to turn to the courts, they can coax government leaders into granting them greater institutional influence and autonomy. Just as national judges can wield the threat of soliciting an international court to bolster their standing within state judiciaries (Alter Reference Alter2014; Pavone and Kelemen Reference Pavone and Kelemen2019), so too can bureaucrats and public agencies leverage the threat of adjudication to empower themselves and challenge the executive chain of command. Judges may not directly benefit from these “big and slow-moving … and invisible” institutional changes (Pierson Reference Pierson, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003), but they are a profound testament to how the presence of courts can reshape politics and policy even where we would not expect it.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000873.

Data Availability Statement

The transparency appendix for this article can be found at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GSO5FP.

Acknowledgments

We thank the APSR editors, three anonymous reviewers, Daniel Naurin, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Tore Wig, Freya Baetens, Neil Ketchley, Geir Ulfstein, Andreas Føllesdal, Mikael Holmgren, Silje Hermansen, Tarald Berge, Vegard Tørstad, Mads Andenæs, Carl Baudenbacher, Chad Westerland, Paul Gardner, Paul Frymer, and Chuck Epp for very helpful comments and suggestions on previous drafts.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was supported by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, project number 223274 (PluriCourts).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.