Introduction

The transition from hunter-gatherer to farming lifestyles involved changes in all aspects of human lifeways: how food was acquired; technology, mobility, settlement and architecture; demography and social relations; ideas of ownership, property and ideology. With such all-encompassing change, farming probably emerged gradually rather than as a Neolithic revolution within each centre of origin. Similarly, the transition is likely to have been a spatially diffuse process, with plant cultivation, animal herding and sedentism developing independently in different localities. New ideas, tools, crops and other items would have flowed through spatially extensive social networks, coalescing in favourable environmental and cultural circumstances to create a diversity of farming lifestyles. Here, we provide further evidence for the social networks that underpinned the emergence of farming in Southwest Asia by outlining a series of previously unrecognised material and symbolic connections between sites in the Northern and Southern Levant.

Göbekli Tepe and WF16 as nodes within a social network

Steps towards farming in Southwest Asia involved the exploitation of wild cereals by Late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers (Weiss et al. Reference Weiss, Wetterstrom, Nadel and Bar-Yosef2004; Snir et al. Reference Snir2015), their cultivation during the tenth to ninth millennium BC by Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) communities in the Middle Euphrates and Southern Levant (e.g. Wilcox & Stordeur Reference Willcox and Stordeur2012; Colledge et al. Reference Colledge, Conolly, Finlayson and Kuijt2018; Weide et al. Reference Weide, Green and Hodgson2022) and the exploitation of legumes, fruits and nuts in eastern regions—today's Iran and Iraq (Asouti & Fuller Reference Asouti and Fuller2013). The first steps towards the domestication of goats are known from the Zagros Mountains in the ninth millennium BC (Zeder & Hesse Reference Zeder and Hesse2000), but, as with cereals and legumes, there were likely multiple loci and different pathways towards such domestication (Stiner et al. Reference Stiner2022). These and other constitutive elements merged to create sedentary communities that were increasingly reliant on domesticated plants and animals: the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B ‘farming villages’, first appearing in the Euphrates Valley c. 9200 BC, rapidly spreading throughout Southwest Asia (Edwards Reference Edwards2016). How plant cultivation and animal herding articulated with changes in climate, population, sedentism, social relations, ideology, notions of property, and cognition have been long debated (e.g. Childe Reference Childe1928; Cohen Reference Cohen1977; Bender Reference Bender1978; Bar-Yosef & Belfer-Cohen Reference Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen1989; Cauvin Reference Cauvin1994, Reference Cauvin2000; Bar-Yosef & Meadow Reference Bar-Yosef, Meadow, Price and Gebauer1995; Hayden Reference Hayden, Price and Gebauer1995; Mithen Reference Mithen1997; Powers & Lehmann Reference Powers and Lehmann2014; Feynman & Ruzmaikin Reference Feynman, Ruzmaikin and Hussain2018; Bowles & Choi Reference Bowles and Choi2019).

The 1994 discovery and excavation of Göbekli Tepe in Upper Mesopotamia (southern Turkey) has influenced this debate in two key ways. With its impressive PPNA art and architecture, dated to between c. 9800 and 8300 BC (Dietrich et al. Reference Dietrich, Köksal-Schmidt, Notroff and Schmidt2013), it places emphasis on ideological change occurring within hunter-gatherer communities (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2012), supporting Cauvin's (Reference Cauvin1994, Reference Cauvin2000) view that developments in cognition and symbolism had priority over economic change during the transition to farming. Second, Göbekli Tepe shifts attention away from the Southern to the Northern Levant, the north also having the wild ancestors of wheat and barley; this has been termed ‘the cradle of agriculture’ (Lev-Yadun et al. Reference Lev-Yadun, Gopher and Abbo2000). Ideology and domestication may have been related: Mithen (Reference Mithen2003: 167) has suggested that the intensive harvesting of wild cereals to feed large gatherings at Göbekli Tepe may have led to domesticated strains as “an accidental by-product of the ideology that drove hunter-gatherers to carve and erect massive pillars of stone”, a view now supported by the evidence for feasting (Dietrich et al. Reference Dietrich2012) and a “massive presence of cereals” at the site (L. Dietrich et al. Reference Dietrich2019: 1).

Göbekli Tepe was likely a gathering place for hunter-gatherers from dispersed residential groups. Seasonal aggregations are a core element of the hierarchal social networks that characterise hunter-gatherers: individuals, families, residential groups, seasonal and periodic gatherings, and regional populations (Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton2007; Bird et al. Reference Bird, Bird, Codding and Zeanah2019). Such networks serve multiple functions: to maintain food security (Whallon Reference Whallon2006; Belfer-Cohen & Goring Morris Reference Belfer-Cohen and Goring-Morris2010); to resolve social tensions and mitigate conflict (Johnson Reference Johnson, Renfrew, Rowlands and Seagraves1982; Clare et al. Reference Clare and Hodder2019); to facilitate cooperation (Apicella et al. Reference Apicella, Marlowe, Fowler and Christakis2012); to achieve reproductive success (Page et al. Reference Page2017); and to maintain population viability (Wobst Reference Wobst1974). The flows of ideas, material culture and people enable dispersed communities to follow similar trajectories of change while maintaining local identities.

Ethnographic accounts for the spatial scale of such social networks (e.g. Bird et al. Reference Bird, Bird, Codding and Zeanah2019) suggest that those of the Late Epipalaeolithic (c. 13 000–10 000 BC) and PPNA (c. 10 000–8200 BC) would have connected people throughout Southwest Asia, approximately 1200km from north to south and 800km east to west. In addition to Göbekli Tepe, gathering places—nodes within the social networks—are likely to be represented by sites with particularly large structures, such as Karahan Tepe, Hallan Çemi and Jerf el Ahmar in the north, and Wadi Hammeh 27, Mallaha and Jericho in the south (Kenyon & Holland Reference Kenyon and Holland1981; Rosenberg & Redding Reference Rosenberg, Redding and Kuijt2002; Stordeur & Abbès Reference Stordeur and Abbès2002; Çelik Reference Çelik2011; Edwards Reference Edwards2013; Finlayson & Makarewicz Reference Finlayson and Makarewicz2018; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. WF16, Göbekli Tepe, Early Neolithic and selected Epipalaeolithic sites of the eleventh to ninth millennia BC (figure © E. Jamieson & authors).

With its large amphitheatre-like building (Structure O75), the site of WF16 is yet another candidate for a seasonal or periodic gathering place in the Southern Levant (Figure 2). WF16 is located at the head of the Wadi Faynan in southern Jordan. Excavated between 2008 and 2010, the site dates to c. 9800–8200 BC, with a focus of activity between 9400 and 9100 BC (Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2018). The bird bones recovered from the site are dominated by raptors (White et al. Reference White2021). Zooarchaeological analysis suggests that the capture of buzzards, predominantly Buteo buteo, during the spring and/or autumn provided an occasion for seasonal gatherings. Performance, ceremony and ritual likely took place within the amphitheatre-like structure, using costume and body decoration made from bird skins, feathers and talons (Mithen Reference Mithen2022; Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2022).

Figure 2. WF16, southern Jordan: a) view west along Wadi Faynan towards Wadi Araba; b) site plan; c) excavation, April 2010; d) Structure O75, looking north-east, underlying a later, free-standing circular structure, O100; e) Structure O75 under excavation, showing decorated face of bench (Figure 5) (figure © S. Mithen and B. Finlayson).

The flow of technology and materials

El-Khiam lithic points—the type-artefact of the PPNA—provide the most striking evidence for the flow of material culture and/or cultural ideas through the Southwest Asian social network. These are found from Jebel Qattar in the far south to Göbekli Tepe in the north, and Hatoula in the west to M'lefaat in the east (Kozlowski & Aurenche Reference Kozlowski and Aurenche2005; Crassard et al. Reference Crassard2013). Geographical variation in the techniques used to make typologically similar points (Crassard et al. Reference Crassard2013) indicates the local expression of a generic idea. Similarly, while the production of large, regular blades becomes widespread during the final PPNA, the naviform knapping methods developed in the Middle Euphrates are distinct from simpler opposed platform techniques of the Southern Levant (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Finlayson, Mithen, Astruc, McCartney, Briois and Kassianidou2019). New finds constantly disrupt understanding of chronology and the direction of movement; for example, the Helwan point had been identified as a marker of north to south flows (Edwards Reference Edwards2016), but has now been found as early in the south as the north (Fujii et al. Reference Fujii, Adachi, Nagaya, Astruc, McCartney, Briois and Kassianidou2019).

The distribution of obsidian also indicates north to south connections during the Epipalaeolithic and PPNA. With major sources in Anatolia, obsidian has been found as cores, flakes and blades at the Natufian site of Mallaha (Khalaily & Valla Reference Khalaily, Valla, Bar-Yosef and Valla2013) and several PPNA sites in the Southern Levant, including Jericho, Netiv Hagdud and Iraq-el Dubb (Ibáñez et al. Reference Ibáñez2016). The low number of obsidian artefacts compared with later periods, and the fact that it was knapped like flint, suggests that the formal exchange networks of the PPNB had yet to be established. Prior to these, obsidian likely passed through the existing social networks of material, technological and information exchange.

WF16 has been proposed as a hub for the exchange of obsidian, malachite, bitumen and marine shell (Goring-Morris & Belfer-Cohen Reference Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen2011). Although the evidence for obsidian is scarce, worked copper ore and other greenstone at WF16 suggests that it was likely a raw material source and an exchange hub for the greenstone beads found at numerous Neolithic sites in the Southern Levant (Kuijt & Goring-Morris Reference Kuijt and Goring-Morris2002). Near-identical double-holed greenstone pendants have been found at WF16 and late Natufian sites in the Jordan Valley (Grosman et al. Reference Grosman2016: fig. 15.6; Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2018: fig. 35.16g). Likewise, more than 400 marine shell beads have been recovered from WF16, comprising a mixture of species from both the Red Sea and Mediterranean (Cerón-Carrasco Reference Cerón-Carrasco, Finlayson and Mithen2007; Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2018). Similar transfers of marine shells from multiple distant sources are evident from Epipalaeolithic sites in the Azraq Basin (Richter et al. Reference Richter, Garrard, Allcock and Maher2011) and central Anatolia (Baysal Reference Baysal2019).

The flow of symbolism and ideology

Compared with the exchange of objects and technology, the flow of symbolism and ideology has appeared more constrained. While Epipalaeolithic and PPNA north–south connections are evident from mortuary practices, notably skull removal (Baird et al. Reference Baird2013; Bocquentin et al. Reference Bocquentin, Kodas and Ortiz2016), visual symbolism has seemed quite different. Based on similarities in zoomorphic art and monumental architecture, Benz & Bauer (Reference Benz and Bauer2015: 13) have suggested there were “common ideological concepts … across northern Mesopotamia in the earliest Holocene”, epitomised by those expressed at Göbekli Tepe, but they were unable to identify that ideology in the Southern Levant. PPNA art works are relatively scarce in the south, with zoomorphic imagery being absent, or at best ambiguous. New finds from WF16 change this situation. Although limited in number, they provide evidence for aspects of shared symbolism between south and north, even if this does not necessarily translate into a shared ideology.

Benches, geometric designs and a monolith

The amphitheatre-like structure at WF16 (Figure 2d) has internal benches, as found within the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe and in communal building EA53 at Jerf el Ahmar, the latter dated to a PPNA/PPNB transition phase of 9000–8495 BC (Stordeur & Abbès Reference Stordeur and Abbès2002). There is a striking similarity between the geometric designs on bench faces at WF16 and EA53. The wet mud plaster at WF16 features a zigzag design, comparable to that at Jerf el Ahmar (Figure 3a). The same design also appears on decorated slabs at Tell ‘Abr 3, forming the front of a bench in Building B2 (c. 9300–8800 BC; Yartah Reference Yartah2004, Reference Yartah2013: figs 9 & 10).

Figure 3. a) Decoration on benches: Jerf el Ahmar (© D. Stordeur. Mission El Kowm-Mureybet. Ministère Affaires Etrangères, France; WF16 © S. Mithen and B. Finlayson); b) WF16 monolith set vertically within a niche formed by the intersection of stone walls within Trench 3, looking west; September 1999 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson).

Shaham & Grosman (Reference Shaham, Grosman, Astruc, McCartney, Briois and Kassianidou2019) have previously noted similarities in the geometric designs incised on stone from Late Epipalaeolithic Nahal Ein Gev II (c. 10 700–10 000 BC; Grosman et al. Reference Grosman2016) and WF16 in the south, and from Tell ‘Abr 3 in the north. We are cautious about drawing conclusions in the absence of a formal statistical study but note that WF16 has a greater abundance of cross-hatched, wavy, zigzag and parallel lines than found elsewhere in the Natufian and PPNA of the Southern Levant, such as at Netiv Hagdud, ZAD2 and Nahal Ein Gev (Bar-Yosef & Gopher Reference Bar-Yosef and Gopher1997; Edwards Reference Edwards2007; Grosman et al. Reference Grosman2016). Such designs are ubiquitous in the north, with those from Tell Qaramel, Tell ‘Abr 3, Göbekli Tepe, Hallan Çemi (Mazurowski Reference Mazurowski2003; Yartah Reference Yartah2004; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg, Özdoğan, Başgelen and Kuniholm2011a; Dietrich Reference Dietrich2021) and others, having similarities to those found on decorated stone vessels, stone plaques and shaft straighteners from WF16 (Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2018: fig. 35.19; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Examples of incised stone vessels: a) Hallan Çemi (redrawn from Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg, Özdoğan, Başgelen and Kuniholm2011a); b) Tell ’Abr 3 (redrawn from Yartah Reference Yartah2004); c) Tell Qaramel (redrawn from Mazurowski Reference Mazurowski2003); d) WF16 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson).

As a further architectural parallel, we note a stone monolith at WF16 (Figure 3b). Although small compared with those at Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe, it sits within a niche of a stone-walled building and is the only PPNA example in the Southern Levant of which we are aware (Finlayson & Mithen Reference Finlayson and Mithen2007).

Snakes and raptors

Snakes are a pervasive theme in the imagery from the Northern Levant and Upper Tigris (Peters & Schmidt Reference Peters and Schmidt2004; Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann2019). They are depicted on stone plaques, shaft-straighteners, monoliths and stone vessels, and are incised, carved in bas-relief and occasionally sculpted in the round, with varying degrees of realism or abstraction (e.g. Figure 5a–d). While open to numerous interpretations, including links to phallocentrism (Hodder & Meskell Reference Hodder and Meskell2011: 239), shamanism (Benz & Bauer Reference Benz and Bauer2015) and evolved phobias (Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann2019), snakes are recognised as central to Early Neolithic ideology from north-western Syria to south-eastern Anatolia.

Figure 5. Snake imagery: a) Nevalı Çori (Hauptmann Reference Hauptmann, Özdögan and Başgelen1999, reproduced with permission of the Euphrates Archive, German Archaeological Institute (L. Clare)/Heidelberg University (J. Maran)); b) Göbekli Tepe D-DAI-IST-GT2002-IW-0001 (© Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Göbekli Tepe Project); c) Göbekli Tepe D-DAI-IST-GT2002-IW-P22_1944 (© Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Göbekli Tepe Project); d) Tell Qaramel (redrawn from Mazurowski Reference Mazurowski2003); e) WF16, SF2078 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson); f) WF16, SF1298 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson).

Figure 5f illustrates a cylindrical stone from WF16, with bas-relief carvings interpreted as snakes. Four tapering wavy lines, one with a forked ending, are spaced evenly around the stone (Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2018: fig. 35.30). It is more heavily worn than other ground stone artefacts from WF16, suggesting either greater antiquity or heavier handling. If the latter, this might indicate a history of exchange through the network and/or extensive ritual use.

The interest in raptors at WF16 is also echoed in the north, with depictions at Göbekli Tepe, Jerf el Ahmar and Tell ‘Abr 3 (Stordeur & Abbès Reference Stordeur and Abbès2002; Yartah Reference Yartah2004; Peters et al. Reference Peters, Von Den Driesch, Pollath and Schmidt2005). These birds have been proposed as symbols of death and as part of a shamanistic ideology (Hodder & Meskell Reference Hodder and Meskell2011; Benz & Bauer Reference Benz and Bauer2015). Raptor bones at Zawi Chemi Shanidar, Jerf el Ahmar and Hallan Çemi suggest that wings, feathers and talons were used in costumes during ritual and performance (Solecki Reference Solecki1977; Gourichon Reference Gourichon, Buitenhuis, Choyke, Mashkour and Al-Shiyab2002; Zeder & Spitzer Reference Zeder and Spitzer2016), as also inferred at WF16 (Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2022).

‘Half-skeletonised’ animals

‘Halb skelettierten’ is the term used by Schmidt (Reference Schmidt, Feldmann and Uthmeier2013) to describe a group of animal and human sculptures from Göbekli Tepe that have prominent ribs (Figure 6a). Precisely what types of animals these depict and whether they represent de-fleshed, excarnated or emaciated creatures is unknown. They may imply death, a theme also expressed by the imagery of wild and dangerous animals in the Northern Levant (Schmidt Reference Schmidt1999; Hodder & Meskell Reference Hodder and Meskell2011). Figure 6b illustrates a carved stone from WF16, also zoomorphic and with incised vertical lines suggesting exposed ribs. Although significantly smaller than the examples from Göbekli Tepe, the similarity is striking. Another zoomorphic comparison is between the finely rendered head of a probable gazelle from Abu Hureyra in the Middle Euphrates Valley and that from WF16 (Figure 6c–d).

Figure 6. Half-skeletonised animals: a) Göbekli Tepe D-DAI-IST-GT1996-DJ-A14 0051 and D-DAI-IST-GT2008-DJ-A61 0004 (© Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Göbekli Tepe Project); b) WF16. SF1365 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson); c) gazelle (?) from Abu Hureyra (redrawn from Moore et al. Reference Moore, Hillman and Legge2000); d) WF16, SF115 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson).

Stone faces

A small face carved in stone from WF16 has greater similarity to that from the contemporaneous site of Jerf el Ahmar in the Middle Euphrates of the Northern Levant than a face from the spatially closer but earlier Epipalaeolithic (Natufian) site of Nahal Ein Gev II (Figure 7). Does this indicate a shared cultural tradition of making small stone faces by PPNA communities living more than 800km apart in Southwest Asia? If so, would the small faces have been used in a similar manner and carried the same symbolic meaning? We note the differences: the Jerf el Ahmar face and others from the Northern Levant have concave backs (Dietrich et al. Reference Dietrich, Notroff and Dietrich2018), while that from WF16 has a face on both sides (Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2018: fig. 35.22). This may represent a further example of the local expression of a generic idea.

Figure 7. Small stone faces: a) WF16, SF238 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson); b) Jerf el Ahmar (Stordeur & Abbès Reference Stordeur and Abbès2002) (© D. Stordeur, Mission El Kowm-Mureybet. Ministère Affaires Etrangères, France); c) Nahal Ein Gev II (Grosman et al. Reference Grosman2017), with kind permission of L. Grosman (© G. Laron).

Phalli

Maleness and ‘phallocentric’ art have been proposed as key themes in the symbolism of the Northern Levant (Cauvin Reference Cauvin2000; Hodder & Meskell Reference Hodder and Meskell2011). Where gender is evident at Göbekli Tepe, male animal and human figures are the most frequent, some having a prominent phallus (Figure 8a). Three ‘stand-alone’ phalli are known from Göbekli Tepe, one of which is 0.8m in length (O. Dietrich et al. Reference Dietrich, Dietrich, Notroff, Becker, Beuger and Müller-Neuhof2019; O. Dietrich pers. comm.). Pillars within an enclosure at Karahan Tepe have been interpreted as representing a ‘penis chamber’ (Thomas Reference Thomas2022)—although this has yet to be academically assessed and published. WF16 has the only conclusive depictions of phalli from the PPNA in the Southern Levant, with several realistic and schematic carvings, one of which is covered in red ochre (Figure 8b). Mithen and colleagues (Reference Mithen, Finlayson and Shaffrey2005) have proposed that the process and equipment of food preparation—mortars and pestles—were embedded in a metaphor of sexual symbolism.

Figure 8. Phalli: a) Göbekli Tepe D-DAI-IST-GT1995-MMA02 (left) and D-DAI-IST-GT1998-KS-AO7 (right) (© Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Göbekli Tepe Project); b) WF16, from left to right: SF2389, SF339, SF1005 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson).

Batons

Figure 9a illustrates a highly polished, long and pointed stone artefact found on the floor of a semi-subterranean structure at WF16. It is made from a fine-grained, pale grey and white stone—the source of which is yet to be determined—and worked to form a fine point. Flake removals at its base suggest that it had been inserted into a haft. As far as we know, there are no comparable artefacts from the Southern Levant. It does, however, have similarities to an artefact from Mureybet in northern Syria, and to a so-called ‘baton’ from Gusir Höyük, located in the Upper Tigris Basin of south-east Turkey, which has two parallel incised lines (Figure 9b–c). Fragments of such batons are described from Hallan Çemi, these being made from soft stone, notched and cigar-shaped (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg, Özdoğan, Başgelen and Kuniholm2011a).

Figure 9. Batons: a) WF16, SF531 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson); b) Mureybet (redrawn from Cauvin Reference Cauvin2000); c) Gusir Höyük (Karul Reference Karul, Özdoğan, Başgelen and Kuniholm2011) (© N. Karul).

The treatment of human bodies

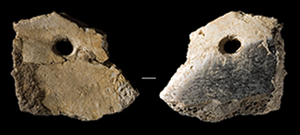

Gresky and colleagues (Reference Gresky, Haelm and Clare2017: 1) describe modified skull fragments from Göbekli Tepe that “could indicate a new, previously undocumented variation of skull cult in the Early Neolithic of Anatolia and the Levant”. The fragments, from three individuals, have deep incisions along their sagittal crests (Figure 10a). In one case, there is a drilled perforation on the left parietal. A fragment of human skull with a drilled perforation has also been recovered from WF16 (Figure 10b). Scattered cranial and mandible fragments from Structure O45 at WF16 suggest that a skull had been displayed, before being smashed when the roof of this structure collapsed (Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2018: 168–70, fig. 14.27).

Figure 10. Drilled human crania: a) Göbekli Tepe (© J. Gresky DAI); b) WF16, SF558 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson). Skulls marked with lines of pigment: (c) WF16, Burial O38 (© S. Mithen and B. Finlayson); d) Hasankeyf Höyük (© Y. Miyake).

The ‘painting’ of human bones was practised at sites in the Upper Tigris Basin. This is prominent at Körtik Tepe, with 58 per cent of 407 skeletons having either red and/or black colouring forming diagonal bands, fine parallel lines, or dotted lines in a plaid pattern (Erdal Reference Erdal2015). Red and black bands were also found on human bones from Demirköy and Hasankeyf Höyük (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg, Özdoğan, Başgelen and Kuniholm2011b; Miyake et al. Reference Miyake2012). Erdal (Reference Erdal2015) suggests that the paint was transferred onto the bones from mats used to wrap the bodies.

Skeletal remains from both primary and secondary burials at WF16 have traces of black pigment, in one case forming parallel black bands on the rear of a skull, as also seen at Hasankeyf Höyük on the Upper Tigris (Figure 10c–d). The WF16 bones often have residual or thick patches of gypsum plaster with impressions of textiles, suggesting that they had been wrapped (Mithen et al. Reference Mithen2018: figs 21.19–20). This use of plaster resonates with practices at Körtik Tepe, also on the Upper Tigris, where entire or partial skeletons were covered with thin layers of gypsum plaster. In some cases, plaster was applied in multiple layers interspersed with paint, suggesting that burials were repeatedly exposed for re-plastering and painting (Erdal Reference Erdal2015)—an interpretation that appears appropriate for WF16. At El-Hemmeh, approximately 50km north of WF16, a seated PPNA burial within a cist had most of the legs, arms and torso covered with white lime or gypsum plaster (Makarewicz & Rose Reference Makarewicz and Rose2011), directly comparable to the practice at Körtik Tepe.

Precedents for the use of both pigment and plaster on human bones come from Late Epipalaeolithic sites in the Southern Levant (c. 10 000 BC). Lime plaster was used to cover burials at Nahal Ein Gev II (Friesem et al. Reference Friesem, Abadi, Shaham and Grosman2019), while pigment, likely from painted wrappings, has been found on skeletal remains from Azraq 18 and Shubayqa 1 (Bocquentin & Garrard Reference Bocquentin and Garrard2016; Richter et al. Reference Richter2019).

Conclusion

The extent to which the small stone face from WF16 is comparable to that from Jerf el Ahmar remains in the eye of the beholder (Figure 7). The same applies to the snakes, half-skeletonised animal, phalli, decorated bench, batons, perforated cranium and treatment of the dead. Are the similarities between these phenomena and those known from the Northern Levant, together with an interest in raptors, coincidental? We suspect not—their range and comparability suggest that cultural convergence is unlikely. Although the same symbols do not necessarily reflect the same ideology, the combination of raptors, snakes, a half-skeletonised animal, and phalli, all represented at a location of social gathering, suggests an ideology at WF16 resonant with that in the north—potentially a specific expression of shamanism (Benz & Bauer Reference Benz and Bauer2015; Mithen Reference Mithen2022). This indicates a more substantive flow of ideas between the south and the north than previously recognised.

The direction of flow, however, remains unclear. With the absence of an Epipalaeolithic record in the vicinity of Göbekli Tepe, and no evident precedent within the known Epipalaeolithic of the Upper Tigris (Benz et al. Reference Benz2015; Kodas et al. Reference Kodas2018), it is unclear from where its art and architecture originated. A local origin may be discovered as new fieldwork reveals the Epipalaeolithic of that region. Alternatively, a Natufian/early PPNA origin in the Southern Levant might be possible, with the ideology materially expressed at Nahal Ein Gev II and WF16 spreading to the north. The abundant wild cereals in that region would have enabled larger and more frequent social gatherings than in the south, providing a context for the ideology to flourish with a more elaborate and monumental expression. Current dating is insufficient to demonstrate that this is the case, although we note the decorated bench at WF16 is earlier than the PPNA/PPNB transition phase at Jerf El Ahmar on the Upper Euphrates, which features a bench embellished with a similar design.

Wherever and whenever the ideas originated, the finds from WF16 indicate that symbols and ideology were flowing along social networks that extended between the far south and the far north of Southwest Asia during the formative millennia, prior to the emergence of farming.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Oliver Dietrich, Julia Gresky, Jens Notroff and Frederick Nitschke for information and images regarding Göbekli Tepe. Similarly, to Leore Grosman regarding Nahal Ein Gev II, Daniel Stordeur for Jerf el Ahmar, Necmi Karul for Gusir Höyük and Yukate Miyake for Hasankeyf Höyük. We are also grateful to the anonymous referees for their helpful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Funding statement

Excavations at WF16 between 2008 and 2010 were funded by the UK Arts & Humanities Research Council (AH/E006205/1).