Article contents

Greek Sling Bullets in Oxford

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 October 2012

Abstract

- Type

- Brief Report

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Authors, the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies and the British School at Athens 1974

References

Notes

1 My sincere thanks to Mr Michael Vickers of the Ashmolean Museum, who generously showed me the collection and gave permission and encouragement to publish it; and to Professors Ernst Badian and Sterling Dow for their helpful advice and comments. This material (some of which is already published and much of which has been accessible for some time) is presented here in the conviction that it deserves to be brought to the attention of a wider public and assumes more importance when considered as a group.

2 For the Minoan bullet, see Evans, A. J., The Palace of Minos (London 1928) ii 344–5.Google Scholar

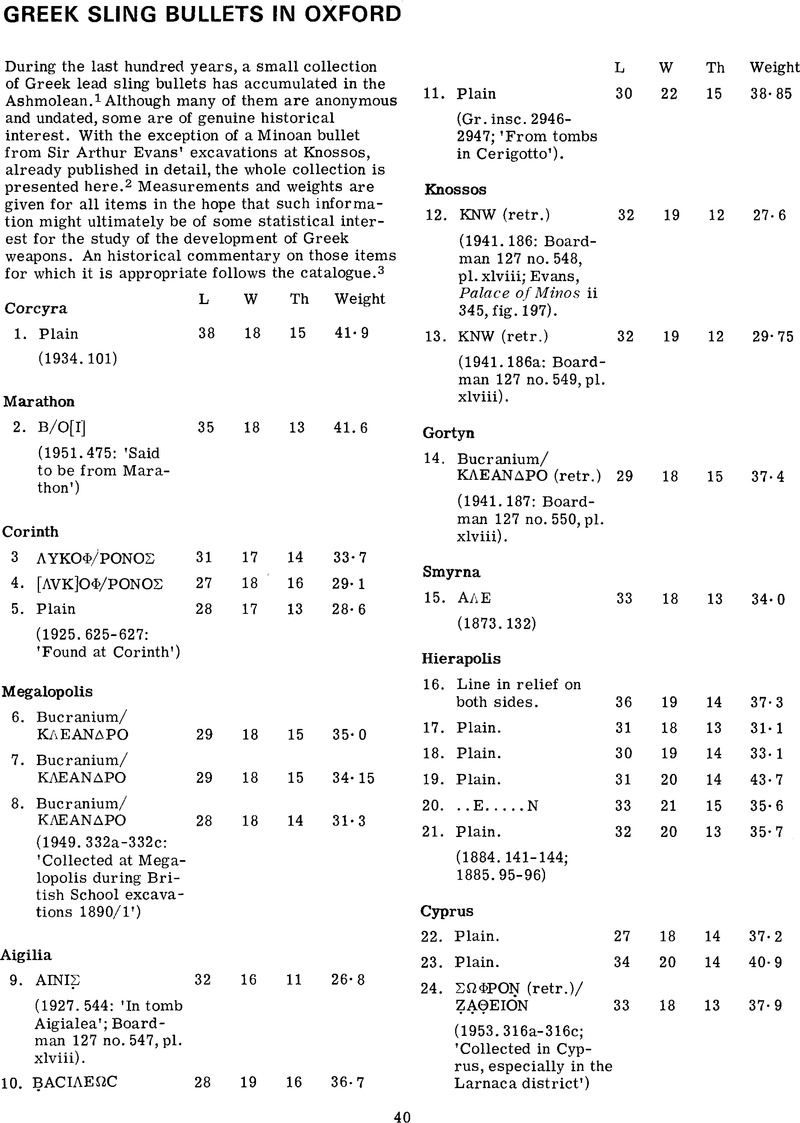

3 In the list which follows, L(ength) W(idth) Th(ickness) are given in millimetres, Weight in grams. Each entry is followed by its accession number in the Ashmolean, together with whatever indication of provenance was to be found. Reference to ‘Boardman’ is to Boardman, J., The Cretan Collection in Oxford (Oxford 1961).Google Scholar

4 For the inscriptions, see Guarducci, M., Epigrafia Greca (Rome 1969) ii 516–524.Google Scholar

5 Vischer, W., ‘Antike Schleudergeschosse’ in Kleine Schriften ii (Leipzig 1878) 260Google Scholar no. 25; cf. 256 no. 23 inscribed with a beta only, both found in Boeotia and at the time in the collection of Major G. Finlay.

6 Head, B.V., Historia Nummorum (Oxford 1911) 348, 352.Google Scholar

7 G. Fougères, ‘glans’ in Daremberg-Saglio 1609. In fact, there is no certain evidence that lead sling bullets were used in the classical Greek world as early as Marathon; for a sketch of the history of these missiles, see Foss, C., ‘A Bullet of Tissaphernes’, JHS xcv (1975) 25–30.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

8 Corinth xii 201. 1525-1527.

9 Thuc. iv 43-44, on which see Stroud, R., ‘Thucydides and the Battle of Solygeia’, Calif. Studies in Class. Antiq.iv (1971) 227–247,Google Scholar a topographical study which shows the accuracy of Thucydides' account.

10 I. Cret. I. 79, nos. 46, 47 (Knossos); Vischer, op. cit. (note 5) 253 no. 14 (from Athens), 272 (in the Heidelberg Museum), 274 no. 272 (in the Basel museum, from Vischer); and H. Heydemann in Hermes xiv (1879) 317 No. 2b (in the Halle museum); no provenance indicated for the last three bullets. The provenance of the Athenian bullet is uncertain, since Athens was then the market for antiquities at which objects from various parts of Greece might have been purchased.

11 For illustrations of the coins, see BMC Central Greece pl. III.

12 Phocians at Megalopolis: Diodorus xvi 39; later career of Phalaecus and his mercenaries: ibid. 61-63. For the importance of the expedition for Cretan history—the first time the island was drawn into the affairs of the mainland—see Kirsten, E., Das dorische Kreta (Würzburg 1942) 60–62.Google Scholar

13 An alternative suggestion would be that Cleander was a commander of Cretan mercenaries in the service of one of the Spartan kings who is known to have used such a force and to have fought at Megalopolis: Areus, Agis III, or Cleomenes. The form of the genitive on the bullets, however, discourages a late dating, and the absence of the name Cleander from Cretan inscriptions (it occurs only on these bullets, and is therefore apparently not a Cretan name) would tend to reinforce the proposed attribution; it occurs with some frequency at Delphi.

14 See the note of Rousopoulos, A. in AE i (1862) 314 f;Google Scholar (p. 315 n. 401). The bullet is illustrated on plate MB’ no. 10. Another bullet with the same inscription was recorded, but not illustrated, by R. Weil in ‘Cythera’,AMv (1880) 243 n.3.

15 Boardman 127 no. 547; for such exclamations, see Guarducci, op. cit. (note 4) 522.

16 See, for example, the long discussion in the Thesaurus of Stephanus, with the references there cited. Note also that the few bullets of Macedonian or Hellenistic kings which have been published bear merely the name of the sovereign, without any title: Philip of Macedon (note 22 below), Alexander the Great (no. 15 in the present collection), and Demetrius Poliorcetes (Vischer 262 no. 32).

17 Rousopoulos, op. cit. (note 14) 315, nos. 398, 402; pl. MB’ 8,12 (latter from same mould as Ashmolean example).

18 Plut. Cleomenes xxxi.

19 Rousopoulos nos. 397-402 and Weil, op, cit. (note 14) 243 n.3 (3 examples).

20 As noted by Weil 243; for the geography of the island, see Philippson, A., Die griechische Landschaften iii 2 (Frankfurt 1959) 518 f.Google Scholar

21 Xenophon, Hell, iv 8. 7–8.Google Scholar

22 Vischer, op. cit. (note 5) 273 no. 64, published one bullet which may possibly be restored to read AΛEΞANΔPOY; for the bullets of Philip, see Olynthus x 431–3.Google Scholar

23 For slingers in Alexander's army, see Berve, H., Das Alexanderreich (Munich 1926) 131Google Scholar (with reference) and 139 for speculation about their origins. The commentary on this bullet owes much to Professor Badian.

24 I. Michaelidou-Nicolaou, ‘Ghiande missili di Cipro’, ASAA xlvii/xlviii (1969/70) 363 no. M265 (illustrated).

25 Ibid. 367 no. 5.

26 Ibid. 368.

27 Ibid. 369.

- 1

- Cited by