‘What do walking, weaving, observing, singing, storytelling, drawing and writing have in common? The answer is that they all proceed along lines of one kind or another.’ (Ingold, Reference Ingold2016, p. 1)

This Special Issue is a philosophical mapping of environmental education. It was conceived of and actualised through two moving colloquia in Koojah (Coogee) Sydney (NSW) and Bilinba (Bilinga) Gold Coast (QLD) from 2018 to 2019. These colloquia symbolised a meeting of bodies, minds and places.

A philosophical mapping has not previously been attempted in environmental education research. In theorising this project, we drew upon Ingold’s (Reference Ingold2015, Reference Ingold2016) concepts of lines, knots and knotting acknowledging that any mapping exercise is retrospective and prospective. Ingold (Reference Ingold2015, p. 14) argues that ‘knots and knotting have largely been sidelined’, rather researchers persist in trying to understand culture (including theory) through conventional and psychological lines of thoughts. Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles (Reference Rousell, Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Malone and Barratt Hacking2020) emphasise the importance on drawing out the ‘relational intensities’ of subjects’ uncommon worlds in environmental education philosophy. In this sense, and akin to de Freitas (Reference de Freitas2014, p. 285), our philosophical pivot point was ‘like a mesh-work of lines … a knot of entangled lines’.

Any philosophical mapping compels a return to questions of what constitutes philosophy. For Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1994), ‘philosophy is the art of forming, inventing, and fabricating concepts’ (p. 2), and ‘concepts are the archipelago or skeletal frame, a spinal column rather than a skull’ (p. 36). To form, invent and fabricate concepts, we leaned heavily into O’Rourke’s (Reference O’Rourke2016) ‘Walking and Mapping’ utilising charcoal, paper and/or a device as we walked-with philosophy. Delineating the philosophical territories of environmental education research was a limiting proposition; thus, we expanded our mapping to embrace environment, the Anthropocene and education.

Walking is certainly not new to environmental education philosophy. Walking for 18th and early-mid 19th century ecological philosophers (Leopold, Reference Leopold1949; Marsh Wolfe, Reference Marsh Wolfe1938; Muir, Reference Muir1901; Thoreau, Reference Thoreau1851–Reference Thoreau1860, Reference Thoreau1854/Reference Thoreau2014) was a steadfast practice in philosophy-making. While journaling remains central to philosophy-making in environmental education (Nazir, Reference Nazir2016), Arts-based research methods are less common. It has only been in very recent times that environmental educators have turned to the Arts in forming, inventing and fabricating concepts (Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles et al., Reference Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Lasczik, Wilks, Logan, Turner and Boyd2020; Lasczik Cutcher & Irwin, Reference Lasczik Cutcher and Irwin2018; Rousell & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Reference Rousell, Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Malone and Barratt Hacking2020; Springgay & Truman, Reference Springgay and Truman2017). Engaging walking inquiry and environmental education through Arts-based modalities is an emergent practice, with its traditions stemming variously from Fine Arts and Indigenous ways of knowing (Lasczik, Rousell, & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Reference Lasczik, Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-KnowlesIn press). Philosophy, in this sense, becomes an art of thinking.

Koojah (Coogee) Colloquia

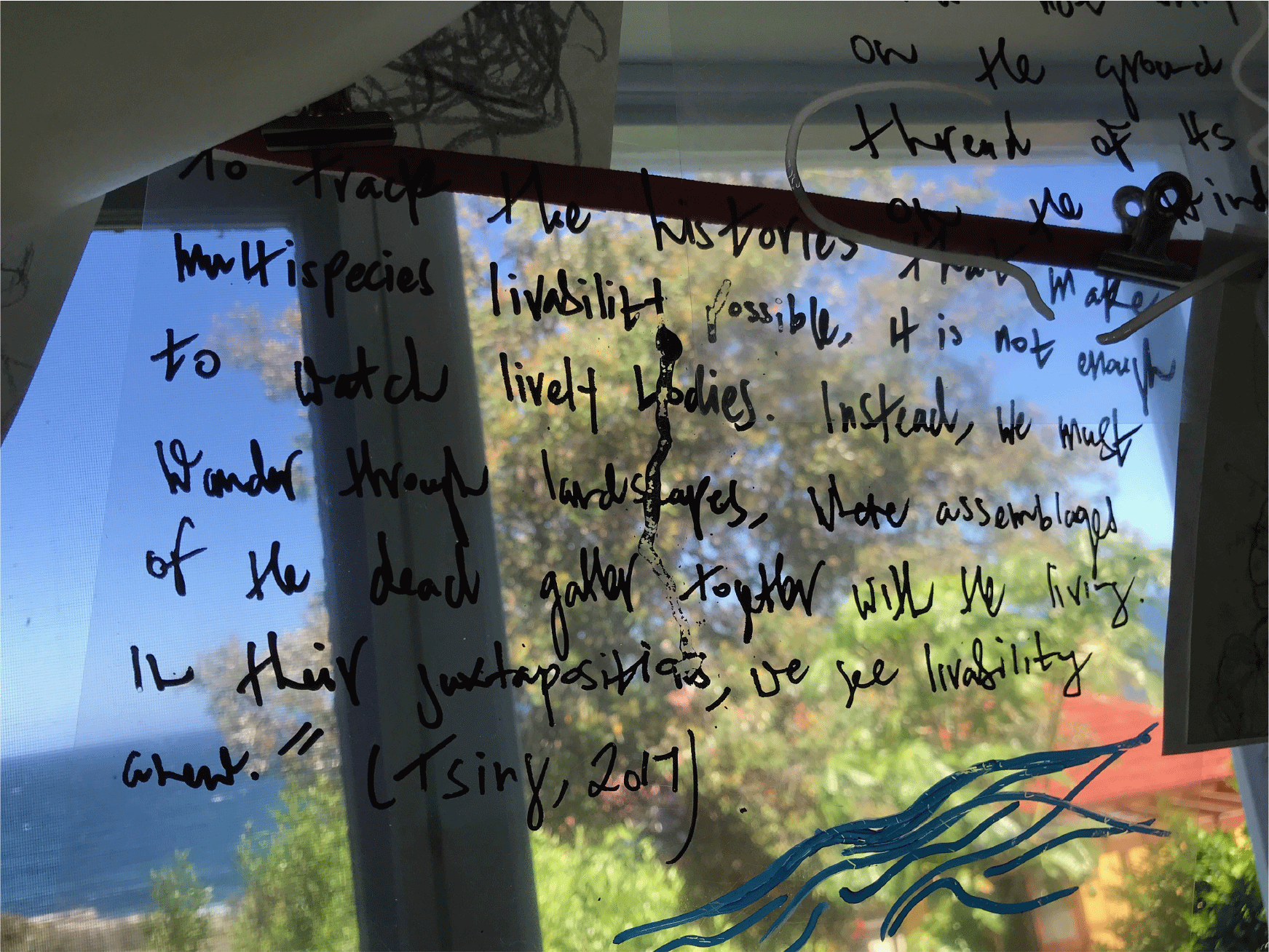

The initial colloquia saw the coming together of 24 philosophers. We commenced with an acknowledgment of the Gadigal and Bidjigal peoples who traditionally occupied the Sydney coast. The colloquia organisers suspended a series of propositions and excerpts from the ceiling and across windows of the colloquia site with the intent to provoke thought (see Figure 1). We presented a protocol to the delegates to walk the propositions, documenting these walks using charcoal on paper over a period of 2 hours. We walked along the rocky cliffs, boardwalks and dwellings of Koojah with propositions in mind and body conceding that ‘mapping is rooted in wayfinding’ (O’Rourke, Reference O’Rourke2016, p. 101). At front of mind was also the acknowledgment that ‘[Philosophers] must no longer accept concepts as a gift, nor merely purify and polish them, but first make and create them, present them and make them convincing’ (Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1994, p. 35). In this context, the purpose of this project became as much about making philosophy as it was about mapping the philosophical lineages in environmental education.

Figure 1. Walking propositions.

When we returned to the colloquia site, we begun the process of weaving initial lines, knots and knottings across/in/through our subjective and uncommon experiences with philosophy in environment, the Anthropocene and education (see Figure 2). We did this by overhanging our charcoal line drawings alongside/across the propositions as further line/knot/knotting makings. It was through these processes that four philosophical concepts or knots began to emerge and were named as traces, shimmer, watery and resonance. We gathered around these concepts and there it begun, a philosophical mapping and making process. We put the concepts to work poetically in the first instance through Hemingway’s six-word story, which we asserted as an enabling constraint (Manning & Massumi, Reference Manning and Massumi2014) and fabulation (see Vignette 1). We did this as a way to begin the knottings. The four concepts knotted us (as four concept groups) for the next 3 months — the time between the first and second colloquia.

Figure 2. Initial lines, knots and knotting in mapping and making philosophical concepts.

Vignette 1. Putting concepts to work poetically.

Bilinba (Bilinga) Gold Coast Colloquia

The site of the second colloquia was Bilinba, Gold Coast, Queensland. The place where we gathered, Southern Cross University, is on Yugambeh Country, a traditional meeting place for Aboriginal clans. We commenced the day with a collaborative foot painting, putting the concepts of traces, shimmer, watery and resonance back to work (see Figure 3). This process was a literal and Arts-based performance of grounding the work to come, consciously, collectively and subjectively shifting and focusing thought through the action and movement of painting with our feet. This experience oriented us in our knottings of theory on that second day. Applying the same protocol as at the first colloquia, we then re-walked the concepts in and through the surrounding landscape as knotted groups taking note of diffractions, collisions and synergies. We documented this next process through mark-marking, photographs, video and soundscape recordings. The process that then followed was the act of writing the four papers that constitute this Special Issue.

Figure 3. Collaborative foot painting.

Traces

The opening paper of this Special Issue, authored by Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Brown, Osborn, Blom, Brown, and Wijesinghe, introduces staying-with the traces of inter/intra-subjective experience, with and within place, in mapping the diverse onto-epistemologies of posthuman and indigenist ways of knowing. This paper commences with Southern Cross University’s (2020) Acknowledgement of Country, extending “awareness of and respect for the living cultures and spiritual connections to Country held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples” (np) and places where this paper was conceived of and written with. Akin with the sentiments of Bawaka Country et al. (Reference Bawaka, Suchet-Pearson, Wright, Lloyd, Tofa, Sweeney and Maymuru2019), this paper is a collaboration between philosophers and Country.

The authors offer a different storying of environmental education philosophy, one that has taken place over thousands of years. They apply staying-with as a method to enacting embodied relational practice, or what Haraway (Reference Haraway2016) describes ‘as mortal critters entwined in myriad unfinished configurations of places, times, matters, meanings’ (p. 1). Five traces were formed — bird, meeting, tree, concrete and watery. Such traces led the authors to the question ‘How are indigenist ways of knowing and Western minority ways meeting, or refusing to meet?’ The authors acknowledge that their paper is a partial response, staying-with their unknowing, holding it open to possibilities of meeting, offering their willingness to ask, to be wrong, to stay-with the messiness and discomfort of now interdependent cultures and they stay-with the traces of connection and mutual becoming.

Shimmer

Malone, Logan, Siegel, Regalado and Wade-Leeuwen walk-with Deborah Bird Rose and her conceptual framing of shimmer. They explore shimmering as incorporating a sensorial richness, as beauty and grandeur, as constantly in flux, moving between past, future and back again. They illuminate the shimmer of past intellectual fervour to demonstrate the time and effort of the ecological struggle, a human failing to heed the warnings that are becoming more apparent as we move through the Anthropocene. Shimmering has potentiality in a posthuman context in its encompassing of spiritual and ancestral energies and illumination of the human (settler) story of exceptionalism. By theorising shimmer with this posthuman lens, they acknowledge and honour the eco-ethico consciousness raised by Australian ecophilosophers and ecofeminists such as Deborah Bird Rose and Val Plumwood, and the social ecologists who have continued to walk with them. A posthumanist perspective takes seriously the need to stop the anthropological machine and contests the production of absolute dividing lines between humans and other worldly matter (Malone, Reference Malone, Malone, Truong and Gray2017). Like Deborah Bird Rose, they support the view ‘an encounter with shimmer may help us better to notice and care for those around us who are in peril’ (Reference Rose, Tsing, Swanson, Gan and Bubandt2017, p. G52) and that includes the Earth itself. In order to disrupt anthropocentricism and present a moral wake-up call that glows from dull to brilliance in these precarious times, they explore environmental education theories from our past and present to find those that will challenge, trouble and disrupt, and help us move into a rapidly changing and uncertain future. Realising the shimmer between new and old theories provides space to return to old ways of knowing and for redefining one’s sense of attachment and connection to a shared world — or to enhance an alternative way for knowing and enlivening multiple ecologies of belonging. This paper attunes and brings attention to the shimmering sensorial beauty of the Earth and the interconnection of all things.

Watery

Lasczik, Rousell, Ofosu-Asare, Foley, Hotko, Khatun and Paquette assemble the conceptual knot of water/watery/watering as a lively, Arts-based cartography of how water may be accounted for when theorising with and through environmental education research. In this paper, the authors challenge the universalising claims of Western technoscience and the colonial logic of extraction, developing an alternative theoretical mapping of environmental education through engagements with Ingold’s (Reference Ingold2015, Reference Ingold2016) concepts of lines, knots and knotting. The concepts of such knottings are defined as an assemblage of haecceities, lived events that are looped, tethered and entangled as material and conceptual agencies that inhere within situated encounters. Thus, this paper grapples with the need to account for water differently in contemporary posthuman ecologies (Braidotti & Bignall, Reference Braidotti and Bignall2019). To overcome anthropocentric and mastery-oriented approaches, various other ways to account for water in science or environmental education will continue to come to the surface, bubbling and rushing like a waterfall as they do in this work. Some of these flows will include thinking with water, which will be central to a theoretical mapping of water that seeks to linger with and embrace sticky knots. This paper contributes to transdisciplinary, posthumanist research on the agency of water within the many contexts and positionings of environmental education, underpinned by artful encounters.

Resonance

Widdop Quinton, Ward, Ahearn and Carapeto take the focusing concept of resonance for an a/r/tographic ‘walk’ to think, be and do differently as a way of challenging humancentric dominances. They attend to knots of resonance interactions in the world, mapping ecological reverberations and diffractions that echo through bodies, through nature encounters, through deep time and through modern spaces. Through art-full, thought-full scholartistic inquiry, resonance is applied as an environmental education conceptual tool for tuning into and harmonising with the entanglements of body-mind-space-time-matter. Drawing on Barad’s (Reference Barad2007) notion of seeking more ethico-onto-epistemological ways, tuning into resonances opens up vibrations and echoes of past–present–future, remembered–experienced–imagined resonances that connect bodies and minds, systems and matter. Common world coherences emerge through attending to all actors and actions that ripple and echo in our ecologies, and for finding resonances between all life and materials in spatial, perceptual and temporal relations. This tuning in is storied in this paper, enabling the reader to walk alongside the authors in their embodied, sensory, affective, textual and Arts-based tuning into the sometimes uncomfortable meshwork of the socioecological collective. Resonance tuning in drew attention to more ethico-onto-epistemological pattern recognition, harmonious relating and encounters with subtle resonances of the ecological collective. The authors present this exploration of resonance as the start of an environmental education knotty theory conversation for shifting into ‘common world’ knowing, being and doing.

Knotting the Knots

In drawing ‘the threads of the argument together’ (p. 172), there are ‘plenty of loose ends for others to follow’ (Ingold, Reference Ingold2016, p. 174). It is neither the end of the line nor the final walk. The philosophical concepts or knots of traces, shimmer, watery and resonance are not independent. Each knot throws out a mobile bridge to the other and beyond. They are the beginning of philosophy, yet always in the middle or ‘milieu’, where the folding and unfolding (or knotting and unknotting) of concepts constitute the ‘absolute ground of philosophy, its earth or deterritorialization, the foundation on which it creates its concepts’ (Deleuze & Guattari, Reference Deleuze and Guattari1994, p. 41). Indeed, ‘drawn threads invariably leave trailing ends that will, in their turn, be drawn into other knots with other threads’ (Ingold, Reference Ingold2016, p. 172).

Acknowledgement

The project was funded by the Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE). The funding was provided to AARE’s Environmental and Sustainability Education (ESE) Special Interest Group (SIG). The SIG co-convenors are Professor Amy Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, Professor Karen Malone and Dr Helen Widdop Quinton.

Conflicts of Interest

None.