No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

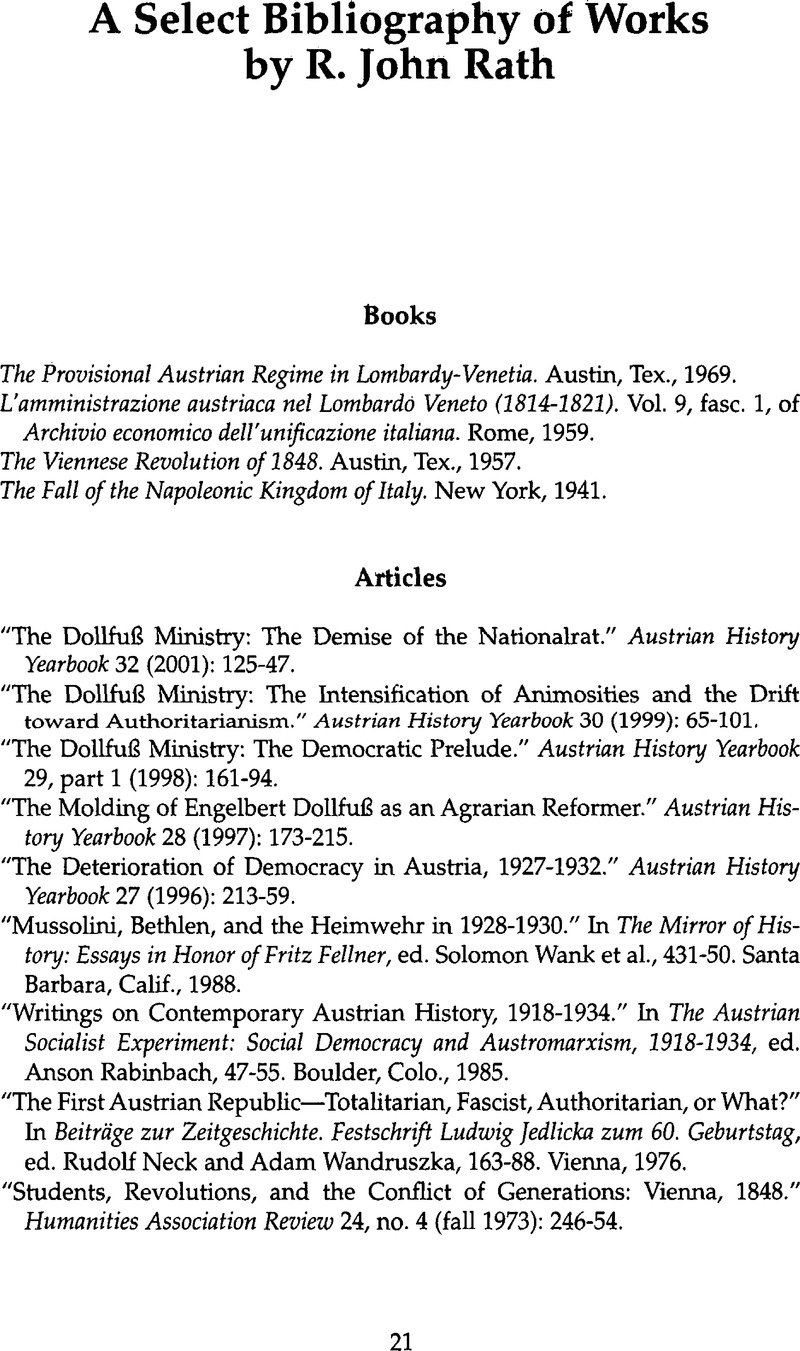

A Select Bibliography of Works

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 February 2009

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- In Tribute to R. John Rath

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota 2001

References

Books

L'amministrazione austriaca nel Lombardo Veneto (1814–1821). Vol. 9, fasc. 1, of Archivio economico delĺunificazione italiana. Rome, 1959.Google Scholar

Articles

“The Dollfufi Ministry: The Demise of the Nationalrat.” Austrian History Yearbook 32 (2001): 125–47.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

“The Dollfufi Ministry: The Intensification of Animosities and the Drift toward Authoritarianism.” Austrian History Yearbook 30 (1999): 65–101.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

“The Dollfufi Ministry: The Democratic Prelude.” Austrian History Yearbook 29, part 1 (1998): 161–94.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

“The Molding of Engelbert Dollfufi as an Agrarian Reformer.” Austrian History Yearbook 28 (1997): 173–215.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

“The Deterioration of Democracy in Austria, 1927–1932.” Austrian History Yearbook 27 (1996): 213–59.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

"Mussolini, Bethlen, and the Heimwehr in 1928–1930.” In The Mirror of History: Essays in Honorof Fritz Fellner, ed. Solomon, Wank et al. , 431–50. Santa Barbara, Calif., 1988.Google Scholar

"Writings on Contemporary Austrian History, 1918–1934.” In The Austrian Socialist Experiment: Social Democracy and Austromarxism, 1918–1934, ed. Anson, Rabinbach, 47–55. Boulder, Colo., 1985.Google Scholar

“The First Austrian Republic—Totalitarian, Fascist, Authoritarian, or What?” In Beitráge zur Zeitgeschichte. Festschrift Ludwig Jedlicka zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. Rudolf, Neck and Adam, Wandruszka, 163–88. Vienna, 1976.Google Scholar

“Students, Revolutions, and the Conflict of Generations: Vienna, 1848.” Humanities Association Review 24, no. 4 (fall 1973): 246–54.Google Scholar

“History, a Science or a Science of Propaganda? An Austrian Example.” Rice University Studies 58, no. 8 (1972): 109–21.Google Scholar

“Authoritarian Austria.” In Native Fascism in the Successor States, 1918–1945, ed. Peter, F. Sugar, 24–43. Santa Barbara, Calif., 1971.Google Scholar

“Das amerikanische Schrifttum über den Untergang der Monarchie.” In Die Auflösung des Habsburgerreiches. Zusammenbruch and Neuorientierung im Donauraum, ed. Plaschka, Richard Georg and Karlheinz, Mack, 236–48.Vienna, 1970.Google Scholar

“The Carbonari: Their Origins, Initiation Rites, and Aims.” American Historical Review 69, no. 2 (01 1964): 353–70.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

“Economic Conditions in Lombardy and Venetia, 1813–1815, and Their Effects on Public Opinion.” Journal of Central European Affairs 23, no. 3 (10 1963): 267–81.Google Scholar

“La costituzione guelfa e i servizi segreti austriaci.” Rassegna Storica del Risorgimento 50, no. 3 (07–09 1963): 343–76.Google Scholar

“Austria, 1955–1961.” In East Central Europe and the World: Developments in the Post–Stalin Era, ed. Kertesz, Stephen D., 338–53. Notre Dame, Ind., 1962.Google Scholar

“Publications and Research Projects of United States Historians in Austrian History.” Der Donauraum 4, no. 2 (1959): 108, 122–32.Google Scholar

“Instructional Problems and Possibilities.” In European History in the South: Opportunities and Problems in Graduate Study, ed. Snell, John L., 7–15. New Orleans, La., 1959.Google Scholar

“Austria.” In The Fate of East Central Europe: Hopes and Failures of American Foreign Policy, ed. Kertesz, Stephen D., 338–57. Notre Dame, Ind., 1956.Google Scholar

“The Viennese Liberals of 1848 and the Nationality Problem.” Journal of Central European Affairs 15, no. 3 (10 1955): 227–39.Google Scholar

“The Failure of an Ideal: The Viennese Revolution of 1848.” Southwestern Social Science Quarterly 34, no. 2 (09 1953): 3–20.Google Scholar

“Early Nineteenth Century Bavarian Religious Laws.” Social Education 14, no. 6 (10 1950): 263–66.Google Scholar

“The Habsburgs and Public Opinion in Lombardy–Venetia, 1814–1815.” In Nationalism and Internationalism: Essays Inscribed to Carlton J. H. Hayes, ed. Edward, Mead Earle, 303–35. New York, 1950.Google Scholar

“History and Citizenship Training in National Socialist Germany.” Social Education 13, no. 7 (11 1949): 309–14.Google Scholar

“History and Citizenship Training: An Austrian Example.” Journal of Modern History 21, no. 3 (09 1949): 227–38.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

“Public Opinion during the Viennese Revolution of 1848.” Journal of Central European Affairs 8, no. 2 (07 1948): 160–80.Google Scholar

“The War and the Austrian Archives.” Journal of Central European Affairs 6, no. 4 (01 1947): 392–96.Google Scholar

“Training for Citizenship in the Austrian Elementary Schools during the Reign of Francis 1.” Journal of Central European Affairs 4, no. 2 (07 1944): 147–64.Google Scholar

“Training for Citizenship, ‘Authoritarian’ Austrian Style.” Journal of Central European Affairs 3, no. 2 (07 1943): 121–46.Google Scholar

“The Austrian Provisional Government in Lombardy–Venetia, 1814–1815.” Journal of Central European Affairs 2, no. 3 (10 1942): 249–66.Google Scholar

“The Habsburgs and the Great Depression in Lombardy–Venetia, 1814–18.” Journal of Modern History 13, no. 3 (09 1941): 305–20.CrossRefGoogle Scholar