Article contents

II. Inscriptions1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 November 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Roman Britain in 1993

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © M.W.C. Hassall and R.S.O. Tomlin 1994. Exclusive Licence to Publish: The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

References

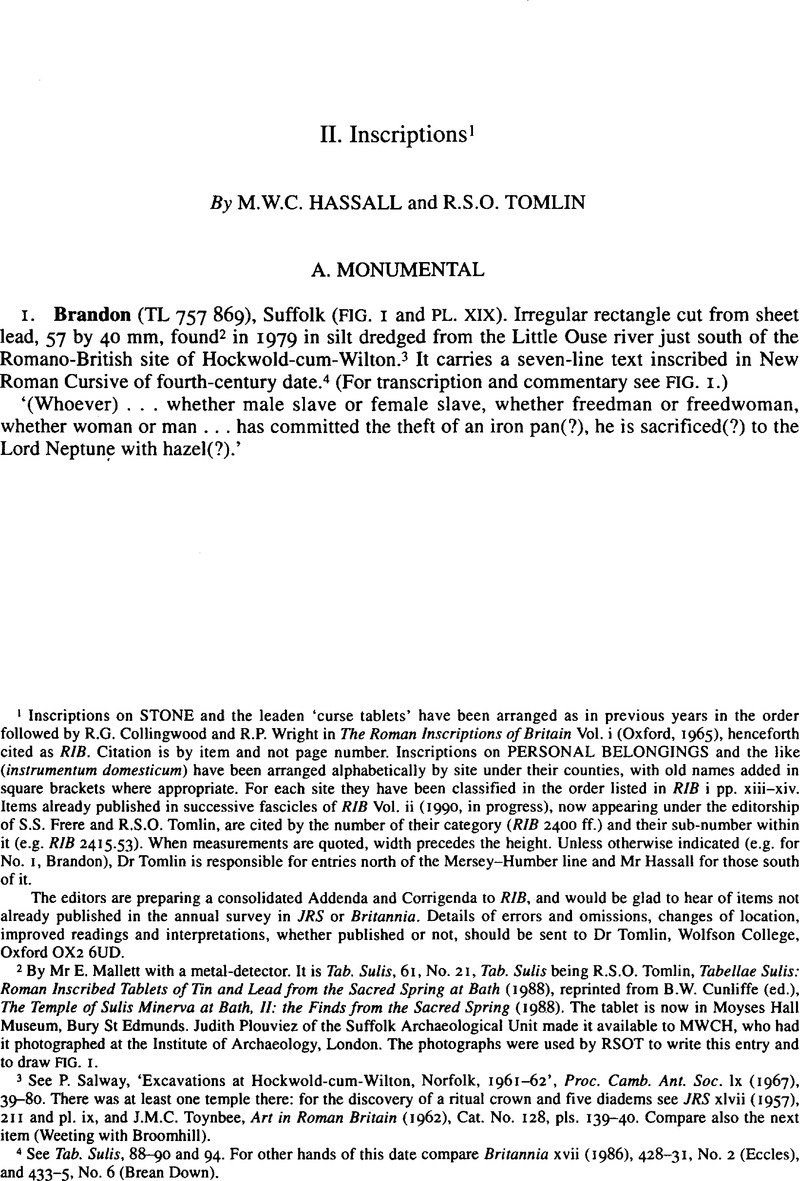

2 By Mr E. Mallett with a metal-detector. It is Tab. Sulis, 61, No. 21, Tab. Sulis being R.S.O. Tomlin, Tabellae Sulis: Roman Inscribed Tablets of Tin and Lead from the Sacred Spring at Bath (1988), reprinted from B.W. Cunliffe (ed.), The Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath, II: the Finds from the Sacred Spring (1988). The tablet is now in Moyses Hall Museum, Bury St Edmunds. Judith Plouviez of the Suffolk Archaeological Unit made it available to MWCH, who had it photographed at the Institute of Archaeology, London. The photographs were used by RSOT to write this entry and to draw FIG. 1.

3 See Salway, P., ‘Excavations at Hockwold-cum-Wilton, Norfolk, 1961-62’, Proc. Camb. Ant. Soc. lx (1967), 39–80Google Scholar. There was at least one temple there: for the discovery of a ritual crown and five diadems see JRS xlvii (1957), 211 and pl. ix, and J.M.C. Toynbee, Art in Roman Britain (1962), Cat. No. 128, pls. 139-40. Compare also the next item (Weeting with Broomhill).Google Scholar

4 See Tab. Sulis, 88-90 and 94. For other hands of this date compare Britannia xvii (1986), 428–31, No. 2 (Eccles), and 433-5, No. 6 (Brean Down).Google Scholar

5 This is a literal transcription: the letters are transcribed as they appear to be, regardless of the scribe's likely confusions (e.g. between V and LI) and his Vulgar spellings. For these see the next note. The one illegible letter (in 3) is represented by a dot.

6 Words have now been separated; modern punctuation, a hyphen, and critical brackets have been added. The square brackets mark the one illegible letter; letters which are legible but remain unexplained are in capitals. Round brackets mark letters either (i) wrongly transcribed by the scribe, or (ii) omitted in error by him, or (iii) which are needed to bring words into conformity with the Classical norm. For these points in detail, see the following Commentary.

1. The reading seems to be clear, but it makes no sense. One might have expected the petitioner's name and a statement of loss (e.g. Tab. Sulis No. 5, Docimedis perdidit manicilia dud), for which there is not really room, or another formula like those in 2-4, e.g. si puer si puella. In view of the scribe's other transcription errors, there may be some here. There is an easy anagram of adversarius, but the residue cannot be resolved.

2-4. For these formulas, which are mutually exclusive alternatives with quasi-legal and religious overtones intended to isolate the thief, see Tab. Sulis, 67-8. Si servus si liber is the most common of them all. The variant si ancilla is found only once (in Tab. Sulis No. 52, line 7, where si servus not si libera should now be restored), but as TLL notes (s.v. ancilla), servus and ancilla are often conjoined.

2. s(i) ser(v)us si anc(i)l(l)a. Si must obviously be restored, but the scribe either wrote V for I (compare the first V in furtum, where again there is no horizontal stroke) or he possibly wrote I twice. The spelling ser(v)us is a frequent Vulgarism (see Tab. Sulis, 75), but ancilla is spelt correctly in Tab. Sulis No. 52. In writing ancela here the scribe was confusing unstressed i and e, and failing to geminate I but the forms ancella (thus in modem Italian) and ancila (thus already in CIL xii. 1412) are both found in post-Roman Latin: see O. Prinz with J. Schneider, Mittellateinisches Wörterbuch, s.v. ancilla.Google Scholar

2-3. si lifbertus si) liberta. Perhaps the scribe began to write liberta in 2, but since this formulation almost always consists of contrasted pairs (the only exception being Tab. Sulis No. 31, si servus si liber si libertinus), it is more likely that his eye slipped. The contrast of ‘freedman’ with ‘freedwoman’ is unparalleled (Tab. Sulis No. 31 comes closest), but it suits the logic of this tablet where the pairings are differentiated not by status but by sex.

3-4. si m(u)lie[r] si baro. For other instances of this pairing see Tab. Sulis, 67; and for baro (‘man’) ibid., 165, and Adams, in Britannia xxiii (1992), 15–17. The scribe wrote MLIER, not a Vulgarism but a visual confusion due to the similarity of V and LI in this hand (in particular compare the V of Neptuno): for another instance of this confusion see Tab. Sulis 97, line 4 (with note), liminibus for luminibus.Google Scholar

4. popia(m) feiire)a(m). For reasons of space the final A was written over R, but otherwise the reading is clear and POPIA at least is inescapable. However, the interpretation is uncertain. The only instance of a word popia seems to be in Goetz, G. (ed.), Corpus Glossariorum Latinorum (1892), iii 366, 30, where it is glossed as ζωμηρυδις(; (‘soup-ladle’, Liddell and Scott), itself glossed as trulla (W. Hilgers, Lateinische Gefässnamen (1969), 293, who notes panna but not popia among its other synonyms). This could then be seen as the object stolen, popia(m) fer(re)a(m) perhaps, ‘an iron pan’: compare Tab. Sulis No. 66, 2 (with note), pannumferri. See further, below.Google Scholar

5. EAENEC. The first two letters EA are certain, and perhaps should be taken as the end of ferrea(m). The other letters are ambiguous, but HOC (i.e. hoc furtum) or MEA (i.e. popia(m) mea(m)) cannot be read.

5-6. The scribe actually wrote FECERE, a Vulgarism due to his confusion again between unstressed 1 and e (made easier still by the two preceding syllables in e) and to the typical omission of the final -t (see Tab. Sulis, 5 for two examples), furtum fecer[it] is a variant of the usual involaverit; compare A. Audollent, Defixionum Tabellae (1904), No. 122 = J. Vives (ed.), Inscripciones Latinas de la España Romana (1971), No. 736, quot mini furti factum est. There is a similar phrase in a fourth-century text from Uley (A. Woodward and P. Leach, The Uley Shrines (1993), 129, No. 68). If popia(m) fer(re)a(m) is indeed the reading in 4, and thus the object of theft, the scribe must have treated furtum fecer(it) as if it were a single word just like involaverit, in other words, he must have compounded it like malefacere. Verbs in -ficare proliferate in Late Latin (V. Väänanen, Introduction au Latin Vulgaire (1981), 93), but furtificare is not attested; yet the adjective furtificus from furtum facere (compare maleficus) is already found in Plautus.

6. domino Neptuno. The water god Neptune is addressed as domine in an unpublished tablet from the Hamble estuary (Tab. Sulis, 61, No. 6). Compare also the tablet from the Thames at London Bridge (Britannia xviii (1987), 360, No. 1)Google Scholar, which is addressed to Metunus, i.e. Neptune. These three tablets were all deposited in rivers. A fourth tablet, from Caistor St Edmund, (Britannia xiii (1982), 408, No. 9), was found on a river bank and is apparently also addressed to Neptune. There is no instance in Audollent, Defixionum Tabellae, of a tablet addressed to Neptune, but most curse tablets were either buried in the ground or dropped into water, and Neptune, like Sulis at Bath and other divinities of springs, was an obvious addressee.Google Scholar

7. cor[u]lo pare(n)tat[u]r. The first letter is now incomplete, but the traces suit C. LI and V are so similar in this hand (see note to m(u)lier above) that it is easy to read CORVLO (‘hazel’, from corulus or corylus) instead of the meaningless CORLILO with its implausible sequence of letters. The elongated final letter (R) marks the end of the text, where a verb may be expected as usual in curse tablets. R then implies the verb-ending -tur; ‘O’ here is almost indistinguishable from V, and the T must be an uncrossed T. The resulting paretatur for parentatur can be explained as due to the indistinct sound of a nasal before a dental in Vulgar Latin: B. Lofstedt, Studien u'ber die Sprache der langobardischen Gesetze (1961), 122, cites examples including CIL xii. 1626, pare(n)tib[us]; and for Britain compare Cove(n)tina (RIB 1531, 1532).

This is the first instance in a British curse tablet of the victim being ‘sacrificed’ to the deity, but the idea is perfectly acceptable: thieves are often ‘devoted’ or ‘given’ to the deity (Tab. Sulis, 63-4), or told to die ‘in the temple’ (Tab. Sulis Nos 5 and 31). Corulo (‘with hazel’), if correct, presents more of a problem. A hypothesis, a guess in fact, is that it alludes to ritual execution: whether by means of a hazel withy round the neck like the Windeby man (P.V. Glob, The Bog People (1969), 166) or by drowning under a hazelwood hurdle (compare Tacitus, Germania XII. 1, etc). Birchwood or willow would be more likely for hurdles, but note the man buried in Undelev Fen with three hazel rods (Glob, op. cit., 68).

7 By Mr C. Marshall with a metal detector. In 1979 he showed it to Tony Gregory of the Norfolk Archaeological Unit, who quickly made the tracing reproduced here. The tablet is noted as Tab. Sulis, 61, No. 20. Mr Marshall swapped it with an unidentified sodalis in the local treasure-hunting fraternity, and its whereabouts are now unknown. We have therefore not seen the original, but Tony Gregory sent the tracing to MWCH, who has discussed it with RSOT, the author of this entry.

8 This is the next parish to the west, the parish boundary in fact dividing the site. See note 3 above, and compare also the previous item (No. I, Brandon).

9 Reading the mirror-image letters from right to left. Defective letters are treated in three ways: (i) if they can be identified with certainty (e.g. S by its loop), they are not marked; (ii) if they consist of a vertical stroke (and thus might be B, D, E, F, H, I, L, N, P, R, or T), they are written as I; (iii) if they are entirely illegible they are marked by a dot. Detailed commentary will be found in the next note.

10 Words have now been separated, hyphens and critical brackets added. The square brackets mark letters either lost or defective (see previous note); round brackets mark letters either (i) wrongly formed or (ii) omitted in error, or (iii) which are needed to bring words into conformity with the Classical norm. For these points in detail, see the following Commentary.

ai. The scribe omitted I, and wrote B for R, because his eye slipped from the first S to the second, and because he retained a memory of B. After liber there is trace of another letter and space for a second; the trace suits Q, and to read [qu]i explains the otherwise redundant T at the beginning of a2 and improves the syntax.

a2. The verbal ending -AVIT looks certain, and the other traces fit furavit. This is a rare synonym for involavit, the Vulgar Latin verb for ‘steal’ usual in British curse tablets. It occurs elsewhere (as furaverit) only in Tab. Sulis No. 98, 6, once again in the Vulgar active form for the Classical deponent (which would be furatus est).

su[st]ulit. Both the syntax, such as it is, and the surviving traces suggest that the same verb occurs here and in b5- Tulit I tulerit is used in the Caerleon curse tablet (RIB 323) and in Tab. Sulis No. 47 in the sense of ‘has stolen’: compare Virgil, Eel. v. 34, postquam te fata tulerunt (‘after the fates snatched you away’, a metaphor of premature death if not assassination). In late Latin tuli comes to be used as the perfect of tollo in this sense of ‘has stolen’: see Adams, in Britannia xxiii (1992), 2–3. Here it is simply a redundant synonym of furavit. Before TVLIT the reading SV[.] is inescapable, which excludes qui or a reference to the object stolen (e.g. res), and one would expect the compounded form sustulit, as in the Veldidena curse tablet (AE 1961, 181). However, the second S cannot be read in a2, and only with difficulty in b5. It is necessary therefore to conjecture that the scribe actually wrote suntulit, as the traces in a2 suggest, whether it was in fact a solecism by him (thinking of contulitf) or a genuine Vulgar form. As quite often happens, the object stolen is not actually stated.Google Scholar

3. [ne ei]. The second vertical of N has been lost, and the diagonal between E and E is casual or part of E. This is the first instance in a British curse tablet of a negative order rendered by ne and the first form of the imperative, instead of the preferred non (nee) and the present subjunctive. It is a colloquialism: see E.C. Woodcock, A New Latin Syntax (1959),, 97.

[ne ei] dimitte. Compare Tab. Sulis No. loo, bi, as modified in ZPE 100 (1994), 104, non Mi dimitta[t]ur; and for the sense of 'forgive' or ‘let go’, see ibid., 106, and Adams, in Britannia xxiii (1992), 18. The construction is that of the pre-Vulgate text of the Lord's Prayer: dimitte nobis debita nostra.Google Scholar

a4. [male]fic(i)um. FICVM is certain, and there is sufficient trace of the first four letters. The scribe may have written I after C., but the letter-spacing suggests not. It is more likely that he confused maleficum (adjectival, ‘something evil’) with maleficium (‘evil-doing’). This confusion was made easier because 1 in hiatus tended to become a semivowel pronounced like y. This is the word's first appearance in British curse-tablet texts, but an unpublished text from Uley (A. Woodward and P. Leach, The Uley Shrines (1993), 130, No. 76) complains of malicious persons qui mihi male cogitant et male faciunt.

d(u)m. The reading DM is inescapable, and the scribe seems to have omitted V by haplography with M. This is the first instance of dum in a British curse tablet; its usage here is similar to that of nisi (see Tab. Sulis, 65) but not quite the same. The use of the indicative vindicas is another colloquialism: see Woodcock, op. cit., 181; and J.N. Adams, The Vulgar Latin of the Letters of Claudius Terentianus (1977), 55.

a5-b2. tu vindi[c]a[s] ante dies nov[e](m). Compare Britannia xviii (1987), 360, No. 1 (London Bridge) (conflating the various versions), ut (t)u me vendicas ante q(u)od ven(iant) die(s) novem. For the formulaic use of vindicare see Tab. Sulis, 68; and for the time-formula compare Tab. Sulis No. 62, ante dies novem, and AE 1929, 228 (Carnuntum), infra dies nove(m). As in the latter text, the final -m has been omitted here because of the tendency not to pronounce it; there are many examples in RIB.Google Scholar

b2-4. si pa[g]a[n]us si mil[e]s. G seems to have been written rather square, with a detached second stroke; like the L in b4, it is somewhat cursive. Otherwise this restoration presents no problems. The formula is unique in curse-tablet texts, but is obviously a new instance of those mutually exclusive alternatives like si servus si liber (ai) intended to isolate the thief: see Tab. Sulis, 67-8. Paganus is the technical and legal term for 'civilian' and is often contrasted with miles, e.g. Vegetius II. 23, si doctrina cesset armorum, nihil paganus distat a milite (‘weapon training is all that distinguishes soldier from civilian’). See further J.F. Gilliam, 'PAGANUS in B.G.U., 696', AJP lxxiii (1952), 75–8Google Scholar = Mavors II. (1986), 65–8; and TLL s.v. paganus, I 2B, 1.Google Scholar

b4-5- [qui] su[s]tu[l]it. Repeated from ai-3; see notes ad loc. The long horizontal stroke of the final T is intended to mark the end of the text. There is just enough space before the apparent ‘T’ for LI, but otherwise this ‘T’ could be read as I and the horizontal stroke attached to a vertical now lost.

11 By Mr J.F. Ridge during the demolition of a cottage in Church Street. It is now in Ribchester Museum. Ben Edwards, the Lancashire County Archaeologist, sent a drawing, photographs and other details.

12 The letters are badly worn, but the only real difficulty is the dedicator's name. We follow Mr Edwards in reading Maru[lla]. Initial MARV seems fairly certain, but then the surface has flaked off (1-2 letters); after that there is a vertical stroke and possibly the corner of L, followed by space for only one letter, which precludes a masculine name in -us.

13 This may be the second dedication to the Matres from Ribchester: see RIB 586. Neither Manilla nor Insequens is particularly distinctive, but it may be noted that of the 18 instances of Insequens in Kajanto (Cognomina, 358), 11 come from Noricum (Mócsy, Nomenclator with CIL iii). The vexillation of ‘Noricans’ attested at Manchester (RIB 576) may thus have been active at Ribchester (compare RIB 591, where the restoration of [No]/ric[orum] must be considered). The relationship of Manilla to Insequens is ambiguous: ellipse is possible either of filia (e.g. RIB 1620) or of uxor (e.g. RIB 1271).

14 By Alan Whitworth, who sent a photograph and full details.

15 For a similar stone see Britannia xix (1988), 495, No. 19Google Scholar. Simple crosses (X) made by two intersecting diagonals are more common: ibid., Nos 14-22; xxii (1991), 297, No. 8, and xxiii (1992), 315, Nos 13-15. For vertical crosses (+) and numerals cut on Wall facing stones, see the notes to these items, and Britannia xxiii (1992), 315, No. 16. They are all thought to mark quarry-batches.Google Scholar

16 With the next item during excavation directed for Cumbria County Council by Wilmott, Tony: see Britannia xxi (1990), 316Google Scholar. For other graffiti found then, see Britannia xxiii (1992), 318–19, and below, Addenda et Corrigenda (c). Rob Perrin of the Central Archaeology Service made them available.Google Scholar

17 The letters are not fully differentiated. The first could be P, and the third A.

18 The first letter and the third are both looped, so the possibilities for each are B, D, P or R. The combination suggested seems the most likely.

19 During excavation for the Chelmsford Excavation Committee directed by Paul Drury. Information on this and the next nine items came from Nick Wickenden who, with R.J. Isserlin, will be publishing the site as a C.B.A. monograph, The Frontage and Other Sites in the Northern Sector of Caesaromagus. This will include work undertaken at a number of other sites in the same area, of which the following produced graffiti: the Orchard Site, behind 21 Moulsham Street, 1969, directed by Rosalind Dunnett (Mrs Niblett, ) (Britannia i (1970), 290); 191–2 Moulsham Street, 1970Google Scholar, directed by Drury, Paul(Britannia ii (1971), 271); Cables Yard, 1972Google Scholar, directed by Drury, Paul(Britannia iv (1973), 301)Google Scholar; Cables Yard, 1973 (no report in Britannia); 23-7 Moulsham Street and Cables Yard, 1975, directed by Drury, Paul(Britannia vii (1976), 342–3). In addition to the graffiti from these excavations published here, the final report will include graffiti from these and other sites in the area, which are neither alphabetic nor numeric. They comprise three groups: (1) Five examples of slashed lines cut before firing on the shoulders of ledge-rimmed jars in local(?) shell-tempered fabric; (2) Seven examples of the symbol ‘X’ cut after firing on sherds from coarse-ware vessels of various forms and fabric. These are unlikely to represent the numeral ‘10’ since other Roman numerals are not in general found as graffiti on the coarse-ware vessels from Chelmsford (contrast the situation with graffiti on samian), and are presumably mostly, if not all, marks of ownership; (3) Ten examples of other symbols (including five ‘lattices’) mostly cut after firing on a variety of coarse-ware vessels.Google Scholar

20 Like all the next nine items except the mortarium (No. 13).

21 The first letter looks as if it were originally cut as R, then re-cut as B, but it seems impossible to take this as BR ligatured, to give the rare cognomen Britta, literally ‘a female inhabitant of Britain’ (Kajanto, Cognomina, 201). Instead it is probably cognate with the Celtic nomen Bittius (see Holder, s.v.) as the feminine form of Bitto (CIL v. 6853).

22 Part of lunius, lunianus, or Junior. But for the other possible reading, compare the next item.

23 The first letter consists of a short but definite vertical stroke connecting at the top with the first stroke of the V, so it is not possible to decide between the alternative readings. Since there is no praenomen beginning with the letters V or N, this cannot be an abbreviated tria nomina; nor is there any common name beginning with the letters VIV (although the nomen Vibius is relatively common) or NIV. An exhortation viv(as) or the word vin(um), retrograde, seem unlikely in this position, underneath the base, and a numeral is more likely: perhaps V I V for VIM, ‘nine’, or n(umero) IV, ‘number 4’. For the third possible reading, IVI V, compare the previous item.

24 Two possible expansions are XX m(anu feci or fecit), ‘I (or he) made twenty’; or XX m(ortaria), ‘Twenty mortaria’.

25 The nomen Iulitius is not attested, but it may be implied by the rare cognomen lulittianus (AE 1947, 1, Samothrace). Kajanto (Cognomina, 171) by implication derives this cognomen from Iulit(t)a, but the two derivations are not mutually exclusive, since the sequence would be lulit(t)a > Iulit(t)ius > Iulit(t)ianus. The alternative, to take lulitio as a mistake for lulitto, seems unlikely since only the feminine form, lulitta, is attested in common with almost all other cognomina ending in the -itta, -itto suffix. (The cognomen Salvitto is a rare exception; ibid., (29.)

26 The first letter could be A or R, and the last letter A or M.

27 During excavation by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust directed by Martin, and Hicks, Alison: see Arch. Cant. ex (1992), 365. The brooch is published by D.F. Mackreth, ibid., 401-3, whom we follow here. Information and a drawing were also provided by Jane Elder.Google Scholar

28 M and E are ligatured; the first letter might also be O, the final letter C. The brooch is Type 20c in M. Feugere, Les Fibules en Gaule méridionale de la conquéte a la fin du V Siécle après J-C (1985), 293-6, but this maker is not attested there, nor in RIB 2421 nor in G. Behrens, 'Römische Fibeln mit Inschrift', Reinecke Festschrift (1950), 1-12.

29 During excavation by the Leicestershire Archaeological Unit directed by Neil Finn. Details and rubbings of this and the next item were provided by Patrick Marsden, Finds Supervisor, Bonner's Lane Post-Excavation Project.

30 Perhaps the initial letters of the owner's tria nomina, for instance G(aius) I(ulius) M(…). The first letter might also be L, for L(ucius), but this seems less likely.

31 This cannot be the capacity in modii if Patrick Marsden is correct in his tentative identification of the amphora, since the Pélichet 47 is said to hold only three or four modii: see the note in RIB ii fasc. 6, p. 33, and compare RIB 2492. 7.

32 During excavation by the Leicestershire Archaeological Unit directed by Aileen Connor. Details and rubbings of this and the next twelve items were provided by Richard Clark, who also made the sherds available.

33 Like all the next twelve items except the mortarium (No. 26).

34 A second diagonal scored line, running from top right to bottom left, parallel to the second stroke of ‘X’, perhaps represents a blundered first attempt, abandoned as being cut too near the rim.

35 During excavation by Mr K. Scott, who made the sherd available to RSOT.

36 The graffito is complete and is an abbreviated personal name. Names beginning with Sen- which incorporate a Celtic name-element are frequent in Britain and Gaul, e.g. Seneca, Senecio, Senîlis, Senecîanus, etc.

37 During rescue excavation by the Museum of London, where Helen Ganiaris made it available to RSOT. For the site see Britannia xviii (1987), 336, and P. Hunting, The Garden House (1987)Google Scholar. For the tablet see Ganiaris, H., ‘Examination and treatment of a wooden writing tablet from London’, The Conservator 14 (1990), 3–9CrossRefGoogle Scholar. There are preliminary reports by RSOT in Antiq. Journ. lxviii (1988), 306, and RIB 2443.19. For his final report see ‘A five-acre wood in Roman Kent’, in J. Bird, M. Hassall, H. Sheldon (eds), Interpreting Roman London: a Collection of Essays in Memory of Hugh Chapman, forthcoming, which is cited here as Hugh Chapman.Google Scholar

38 The drawing excludes traces of a previous text, which can be seen by comparing FIG. 4 with PL. XX. The reading is discussed in detail in Hugh Chapman (see note 37 above), but note that -bus of heredibus (7) has been added below the line, and that half a line has been inserted between 7 and 8. The latter is apparently the name of a neighbouring proprietor now represented by his ‘heirs’, which was added by the scribe after he had accidentally omitted it. In 11 and 13 the cognomen Betucus was read originally (see note 37 above), but Bellicus is the correct reading.

39 There is a fuller commentary in Hugh Chapman (see note 37 above), but note in particular: 3. Cum ventum esset in rem praesentem is a well-attested technical legal phrase (see TLL s.v. praesens i.3) used when the boundaries of land or its ownership were in dispute, and refers to the arrival of the judge and parties concerned at the property in question. For other legal terminology see 5 ff. below, and Hugh Chapman. 4. Verlucionium is a variant of the British place-name Verlucio, for which see Rivet and Smith, PNRB s.v. Leuca and Verlucio. The word is of Celtic etymology, containing the intensive prefix *ver and the adjective leuco, ‘bright, shining, white’, cognate with Latin lux (‘light’) and lucus (a small wood, especially in the sense of a ‘sacred grove’). See Hugh Chapman for the suggestion that it may have been a pre-Roman sacred grove which had fallen into private hands. According to the ancient commentator Agennius Urbicus in C. Thulin (ed.). Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum, 48, sacred places were legally the property of the Roman People, and governors of imperial provinces were expressly told by the Emperor to see that they remained so. But in Italy and the provinces sacred groves (lucos sacros) often passed illicitly into private hands, and ownership was disputed between the State and individuals.

5. arepennia: see TLL and Holder, Alt-celtischer Sprachschatz, s.v. arepennis. There are minor variations in spelling, but a neuter form (whether in -e or -ium) is otherwise unattested. The word is of Celtic etymology and was current in Gaul and Spain as a unit of area-measurement, but it was nonetheless a Roman unit, since it was one actus (120 Roman feet) square, that is half of one iugerum. One arepennis is thus equivalent to 1,495 square yards, and fifteen to 4.6 acres. The use of this technical term and that of via vicinalis (see below) may imply that the civitas Cantiacorum had been professionally surveyed; this would be required for the Census in any case.

5ff. The wood is located in the proper legal form, by the names of the civitas and pagus in which it lies, and the names of two neighbouring proprietors (adfines): compare Digest L.15.4, and the Italian alimentary tables (e.g. ILS 6675).

6. in civitate Cantiacorum: Rivet and Smith, PNRB s.v. Cantiaci, have already argued that this is the correct form. The present text proves them right. Note also that CANT'm RIB 192 should be resolved as Cant(iacus), not Cant(ius).

pago Dibussu[ ]: the pagus was a geographical sub-division of a civitas, the term ‘parish’ being the nearest modern equivalent, but of course an anachronism. This is the first British pagus to be named explicitly, but unfortunately the reading is uncertain. There does not seem to be any convincing analogy or etymology for the name (though note Rivet and Smith, PNRB s.v. Dubabissum).

8-9. via vicinale: a ‘vicinal’ road is defined by Siculus Flaccus in C. Thulin (ed.), Corpus Agrimensorum Romanorum, 109, as a minor road relative to a major road (via publica), whose upkeep was the responsibility of local landowners under the supervision of the ‘parish’ authorities (magistri pagi). It led from a major road into the hinterland, and often served as a land boundary, being mentioned in conveyances (in emptionibus agrorum). Vicinale is a solecism for the proper ablative vicinali.

8-11. Caesennius Vitalis, lulius Bellicus, Valerius Silvinus: Roman citizens but otherwise unknown. The name Caesennius suggests an Italian, perhaps Etruscan, origin; a connection with Caesennius Silvanus, military tribune in Britain in c. 103 (Pliny, ep. III. 8), is possible, but seems unlikely. Julius and Valerius suggest provincial origins, particularly Cisalpine or Transalpine Gaul, or Spain, the descendants of provincials enfranchised in the late Republic; both nomina are very common among legionaries. The cognomen Bellicus is of Celtic etymology and is well attested in Gaul and Britain. None of these landowners, to judge by his name, was of British origin.

11. Roman land-prices are discussed by R. Duncan-Jones, The Economy of the Roman Empire (1982), 48-52, and since Egypt is ‘the one part of the Empire where numbers of actual land prices are known’, this would seem to be the first explicit land-price from elsewhere. See Hugh Chapman for an attempt to place it in context.

40 During excavation by the Museum of London's Department of Greater London Archaeology directed by Robin Densem. Angela Wardle provided details and the drawing reproduced here, and made the object available. For the site see ‘Excavations at the Courage Brewery and Park Street 1984-90’, London Archaeologist 6 No. 10 (Spring 1991), 255–62, and especially 257, fig. 3, area 2. The object will be No. 4L01 in the forthcoming corpus of Roman military equipment from London by M.C. Bishop and others.Google Scholar

41 R is of cursive form, L is made with a second short diagonal stroke. Centuria is indicated, exceptionally, by C unreversed.

42 By Mr Rod Halsey with a metal detector, and by him presented to the Castle Museum, Norwich. David Gumey of Norfolk Landscape Archaeology (Norfolk Museums Service) provided details, the drawing reproduced here, and a photograph.

43 The sealing is thus later than the Severan division of the province (for the date see A.R. Birley, The Fasti of Roman Britain (1981), 168-72). It is the second such sealing to have been found, but the other (RIB 2411.37) abbreviates the legend to four letters (P R B S) and depicts the stag couchant. Three sealings of the complementary northern province, Britannia Inferior, are also known: RIB 2411.34, 35 and 36.

44 Like the next two items, by M r D. Fox with a metal detector, in whose possession they remain. David Gurney (see note 42 above) provided details and photographs. For the site see Britannia xix (1988), 456.Google Scholar

45 The tails of both Rs have been crossed. The second stroke of V at the end of line I is very worn, and S after it may have been lost entirely; but it looks more as if the inscription was confined to the flattened face of the ring, and that S in line 2 completed Matribus. It is uncertain whether the remaining letters are the abbreviated name of the dedicator or an abbreviated epithet of the Matres. The latter seems more likely, especially if ‘I’ were taken to be T (compare the T in line I ) and the medial point to be repeated in error; TR could then be understood as tr(ansmarinis). There are six instances of Tra(ns)marinae as an epithet of the Matres in Britain (RIB Index, 74). For rings dedicated to the Matres see RIB 2422.9 and 28, and an unpublished silver ring from Vindolanda.

46 This is the sixth ring from Britain inscribed TOT; for the others see RIB 2422.36-40. The Celtic god Toutatis, identified with Mars, is attested in Britain by two dedications (RIB 219 and 1017) and a graffito on a pot (Britannia ix (1978), 478, No. 41).Google Scholar

47 For other silver rings from Britain inscribed Mer(curio) or Deo Mer(curio) see RIB 2422.20, 29 and 30. The gold ring given(?) to Mercury at Uley (A. Woodward and P. Leach, The Uley Shrines (1993), 123) is not really comparable, since it was presumably stolen property. That Mercury was worshipped at the Great Walsingham / Wighton temple site is shown by the discovery there of three bronze statuettes of the god: see Britannia xix (1988), 456 and pi. XXVI.Google Scholar

48 During excavation directed b y D.S. Neal on behalf of English Heritage. For the site see Neal, D.S., ‘The Stanwick villa, Northants: an interim report on the excavations of 1984-88’, Britannia xx (1989), 149–68. Rob Perin of the Central Archaeology Service made the jar available and provided details.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

49 S in particular is uncertain. What survives resembles G, that is a curved stroke like C and a short second stroke interpreted doubtfully as the unfinished tail of S. The graffito is presumably the potter's signature, but the name Cravirius is otherwise unattested.

50 By Mr Eric Lawes with a metal-detector; and thanks to his admirable self-restraint it was properly excavated by the Suffolk Archaeological Unit directed by Judith Plouviez.

51 See above, pp. 165-73.

52 Compiled by RSO T from R. Bland and C. Johns, The Hoxne Treasure: an Illustrated Introduction (1993) and other information provided by Catherine Johns.

53 Illustrated in Bland and Johns, op. cit. (in note 52), 22-3. The ‘capitals’ retain the form of the brush-strokes which must have preceded them: note the curving down-stroke of R, that the cross-bar of F begins well to the left of the upright like ‘I’ (the second stroke has been omitted, presumably by mistake), that the second stroke of L is a diagonal which begins mid-way down the upright, the peculiar D consists of a small loop mid-way down the upright stroke, O is flattened, the strokes of M are diagonal, both As are open and the first is ‘cursive’ (the first diagonal meets the second mid-way), and the second stroke of N is narrow.

54 tuliane for luliana, the masculine vocative form by mistake for the even less familiar feminine. (Compare the confusion over the termination of Datiane, item No. 73.) The gender is guaranteed by domina.

55 Ursicinus is quite a common late-Roman name (for examples see PLRE, Vol. i, and Diehl, ILCV, s.v.), but this man is unlikely to have been one of the known office-holders, wh o would have called themselves Flavius Ursicinus.

56 Inscriptions within the bowls of Roman spoons usually read from left to right if held in the right hand; that this was intentional is implied by one of the two Peregrinus vivat spoons which the craftsman began by engraving left-handed, realised his mistake, and started again right-handed. (See further, note 59 below.) This spoon (No. 73), however, would have to be held in the left hand to be read.

57 The lettering is irregular, unlike the careful capitals of the other spoons. The first letter is apparently a D formed like that in the domina luliane text (No. 62, see note 53 above). The first three As are open. Both Is are heavily serifed top and bottom. By reading the peculiar D as P, the name could be seen as a blundered PATAVINE, from Patavinus, but this rare north-Italian cognomen is most unlikely here; it is much easier to understand a vocative in -ae (a Vulgar hyper-correction of the unfamiliar vocative in -e) and the name as a blundered Datianus. (The scribe simply inserted I before the wrong A; a similar mistake occurs in the blundered Perseveranti vivas of a spoon in the Thetford Treasure (RIB 2420. 35).) Datianus, developed from the cognomen Datus, is the name of an African martyr (ILCV 2068) and the consul of 358, among others, and is recognizably late-Roman.

58 The name Euherius is not attested as such, and there are two possible restorations, both names of Greek etymology. Unfortunately the usual wa y in which Greek Chi [kh] and Greek Theta [th] were taken into Latin is n o help towards deciding which to choose here: Greek [kh] in Vulgar Latin followed the pronunciation to become [k] (thus Eucerius) and [th] to become [t] (thus Euterius). On the other hand, Euharia for Eucharia is actually found, in ILCV 1423 (Boppard). This provides an analogy for Eu(c)herius, but since Eutherius occurs as a Greek graffito on two plates in the Mildenhall Treasure (RIB 2414. 5 and 6) it is also an attractive possibility. For the moment the question must remain open.

59 G is of cursive form indistinguishable from capital S. A n inverted text underlies VIVAT on one bowl, notably G under V, E under I, and R under V; there also seems to be trace of E under A, and I under S of Peregrinus. The craftsman evidently began to engrave PEREGRINVS left-handed, realised his mistake and, inverting the bowl, began again.

60 Peregrinus is a common cognomen, but it became popular with Christians (see Kajanto, Cognomina, 313) in its developed sense of ‘stranger’ (in this world) or ‘pilgrim’. It occurs in a fourth-century text from Bath (Tab. Sulis No. 98, 14).

61 If this is also an abbreviated name, the most likely candidates are Publicius and Pudens (and its cognates), but there are other possibilities; in particular note Publianus on a bowl in the Water Newton (Chesterton) Treasure (RIB2414. 2).

62 The text is legible by X-ray photograph. The three inscriptions are of identical form; in particular the Q is ‘cursive’ with a small circle and long tail, and the two Ss are oddly close together. The transmitted reading Quis sunt vivat or even Qui<s> sunt vivat makes no sense, and indeed is ungrammatical; instead, this is a text of Peregrinus vivat form, in which the name has been blundered. This in fact is presumably why the text was erased. The craftsman may have simply committed an anagram error (compare No. 73, DATANIAE for Datian<a>e), but if he were semi-literate and the original text had been written in New Roman Cursive (for a tabulation of letter-forms see Tab. Sulis, p. 94), it would have been quite easy for him to read QVINTVS as QVISSVNT: he only had to read NTVS as SSVNT. N and the second (cross-bar) stroke of T would look rather like SS: compare the NT of dederit nee (reversed) of Tab. Sulis No. 98, 8, with SS in Pisso (reversed), ibid., 10. In an angular New Roman Cursive hand, N can be indistinguishable from V: for examples see Tab. Sulis No. 100, where the reading is determined by the context. If T was ligatured to V (see ut reversed in Tab. Sulis No. 98, 2, for an example), and the downstroke of T was looped at the bottom, the result could be quite like VN: compare Latinus reversed, ibid., 15. Finally S, if the upstroke were incomplete (compare those in Tab. Sulis No. 100, 1), could be mistaken for T. Hence the nonsensical QVISSVNT. The praenomen Quintus is very common as a cognomen (Kajanto, Cognomina, 174) and there are seven or eight instances in ILCV of its being used by itself in the late-Roman period.

63 AN is ligatured, but the possible reading SAVC can be rejected; likewise an alternative expansion of SANC, sanc(tum) (‘holy’), which seems rather fanciful. The cognomen Sanctus and its cognates were popular in Gaul, probably because they contained a Celtic name-element; compare Britannia xviii (1987), 360, No. 1, 07 and 10, Santinus and Santus. For a Bishop Sanctinus in sub-Roman Wales see Nash-Williams, ECMW, No. 83.Google Scholar

64 For this arch language compare RIB 2420. 48 (Canterbury), viri boni s(u)m, ‘I am (the property) of a good man’. For the name see next note.

65 Compare RIB 2420. 40 and 41 (Thetford), Silviola vivas, almost the identical inscription ‘on spoons of closely similar form’ [Catherine Johns]. In view of this similarity, and the closeness in date and place of the Thetford and Hoxne Treasures, it is likely that Silvicola was intended at Thetford. (The omission of C before O would have been an easy visual slip.) Neither name is common, but the feminine Silviola, although an acceptable diminutive of Silvia, is only once attested (ILCV 3727 B, Rome), whereas the masculine Silvicola is a Latin adjective (‘woodland-dweller’) analogous with Agricola (‘field-dweller’ i.e. ‘farmer’) and is already attested in Britain (Britannia xviii (1987), 360, No. 1, b3~4) as well as once in Gaul (CIL xiii. 2016). Silvicola, which may in fact have been a formal epithet of the god Faunus (compare Virgil, Aen. x. 551), would be a particularly appropriate personal name in the context of the Thetford Treasure with its wealth of Faunus epithets.Google Scholar

66 Compare RIB 2420.47 (Thetford), where vir bone is taken to be a general invocation, not the vocative of a personal name Virbonus.

67 During excavation for HBMC and Suffolk County Council (see Britannia xvii (1986), 404) directed by Judith Plouviez, who sent the drawing reproduced here and other details to RSOT.Google Scholar

68 The genius was the essential character, the guardian spirit of a person, an institution, a place; thus dedications to genius loci (‘the spirit of the place’) are frequent. What B(…) meant is now lost, but it was self-evident to the writer; most likely the place of manufacture.

69 By metal detector. The ring is now in Sheffield City Museum. Dr M.J. Dearne sent information and a copy of a drawing by Julian Parsons to MWCH.

70 Presumably the owner's initial, though that o f a deity is also possible. Compare items Nos 37- 9 above, and others in RIB 2422, for example RIB 2422.21, an octagonal silver ring from York inscribed Deo Sucelo.

71 During excavation in advance of the new Al motorway directed by Dr M.C. Bishop, who sent the drawing reproduced here and other details. He writes: ‘All three phases o f Roman military occupation seem to be Flavian, falling within a likely date range o f A.D. 71-85.’

72 Trenus and Catus are both Celtic personal names already attested in Britain. For Trenus see CIL xvi. 49, Lucconi Treni fiilio) Dobunn(o); and for Catus RIB 154 as defined in Tab. Sulis No. 4, 7; compare JRS xlvi (1956), 150, No. 28Google Scholar, Cata; JRS lvi (1966), 223, No. 37, Catti.Google Scholar

73 During excavation by the Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust directed by Dr E.M. Evans, who provided details: see also Britannia xvi (1985), 259; xvii (1986), 366; and xviii (1987). 307. The fragment is now in the Roman Legionary Museum, Caerleon, where David Zienkiewicz made it available to RSOT and provided the drawing reproduced here and photographs.Google Scholar

74 See C. Heron and A.M. Pollard, ‘The analysis of natural resinous materials from Roman amphoras’, in E.A. Slater and J.O. Tate (eds), Science and Archaeology, Glasgow 1987 (1988), 429-47.

75 Thus D.P.S. Peacock and D.F. Williams, Amphorae and the Roman Economy (1986), 102, who also observe (ibid., 15) that six different fabrics of ‘Rhodian’ amphoras have been identified, perhaps two of them from Rhodes itself. Note CIL iv. 9327 = A. Maiuri, La Casa del Menandro (1933), 485, No. 33 (with a photograph), a ‘Rhodian’ amphora from Pompeii which contained Rhodian raisin wine; a dipinto reads PASS " RHOD I P. · COELI · GALLI, pass(um) Rhod(ium) P(ubli) Coeli Galli. Compare also CIL iv. 9323, an amphora of the same type, which bears the dipinto PA I DEF, probably pa(ssum) deflrutum), ‘concentrated raisin wine’. David Zienkiewicz informs us that David Williams and Stephanie Martin-Kilcher both attribute the Caerleon amphora almost certainly to Crete. Some ‘Rhodian’ amphoras at Pompeii explicitly come from Crete: note Cret(icum) exc(ellens) (CIL iv. 5526) and ‘Gortynian’ (from Gortyn, the capital of Crete) (CIL iv. 6326-8). There is also good literary evidence. The best raisin wine came from Crete according to Pliny, NH XIV. 81; passum Creticum is specified in prescriptions by the Claudian doctor Scribonius Largus (Conpositiones, 30, 63, 65, 74); Martial (epig. XIII. 106) calls it the poor man's mulsum (honey-sweetened wine); compare Athenaeus, Deipn. XIV. 645, a Cretan cake made of grape syrup. When Juvenal wants an image of a high-profit, high-risk occupation, he cites the merchant who ships Cretan passum in Cretan amphoras out into the Atlantic (Sat. XIV., 267 ff., esp. 270-1). Peacock and Williams, op. cit., 103, note that some ‘Rhodian’ amphoras contained figs. The other possibility is honey, which is specified in an unpublished Greek dipinto on a ‘Rhodian’ amphora from London, now in the Museum of London.

76 G is indistinguishable from C. We expand the legend conventionally in the genitive case, but the dative would also be possible: Leg(ioni) II Aug(ustae), ‘For the Second Legion Augusta’.

77 The reading and interpretation must remain uncertain until a parallel is found; it resembles CIL iv. 9479, an undeciphered dipinto from Pompeii. Line 1: three sinuous down-strokes which look like a numeral; compare RIB 2492.13 (London), probably a ‘Rhodian’ amphora, where line 1 of the horizontal dipinto certainly reads: HI, ‘three’. Line 2: the first two letters might also be M or RR, but less likely, judging by their forms in line 3. Lines I and 2 may be a note of capacity, or perhaps a control-mark of some kind. Line 3: PER looks certain, and may be either the preposition per or the first three letters of a proper name (note that the initial P is enlarged); the next three letters are best taken as PRI (the I with a rightward serif); then the last three letters are increasingly faint, but look like N(or M)VM. PERPRIMVM might be expected to identify the contents, vinum (‘wine’) or rather passum understood. We offer the first of two possible interpretations, primum with the intensive prefix per-, i.e. perprimum, ‘the very first’. This adjective perprimus is not attested, but per is often thus used to intensify adjectives, even superlatives (permaximus and perminimus). ‘First’ is an appropriate grading for export-quality raisin wine (see above, note 75): after the raisins had been pressed, water was added to the skins to make ‘second-grade’ wine, secundarium passum (Pliny, AW XIV. 81-2). Alternatively PER is an abbreviated place-name adjective of a wine qualified as primum. Per(…) would have been a note intelligible to the writer; one possibility is Per(gamenum) from Pergamum in Crete. This was a Cretan port (Pliny NH IV. 59), though an obscure one; it is the only Cretan city whose name began with PER (see the exhaustive lists by Faure, P. in Kretica Chronica xiii (1959), 171 ff. and xvii (1963), 16 ff.).Google Scholar

78 By Mr R.J. Hilliard with a metal-detector, and by him submitted to Norwich Castle Museum for identification. Barbara Green and John Davies, successive Keepers of Archaeology there, made it available to RSOT.

79 The site is Roman (B.C. Burnham and J. Wacher, The ‘Small Towns’ of Roman Britain (1990), 203-8), but some medieval material is said to have been found there. Although this object resembles a Roman ownership-tag, and is inscribed in Latin, the letter-forms are not Roman. There is a damaged three-line text on the reverse, of which the first two lines seem to be identical with those of the obverse.

80 Information from David Sherlock, Inspector of Ancient Monuments.

81 Information from David Sherlock.

82 It was seen in the undercroft by RSOT in 1977, but was missing by 1981.

83 Johns, C. and Painter, K., ‘The Risley Park Lanx “rediscovered”’, Minerva ii 6 (Nov/Dec 1991), 6–13. We are grateful to the authors for allowing RSOT to summarise their interim report here.Google Scholar

84 G of BOGIENSI is damaged, only the upper loop surviving, but Stukeley's reading should be preferred to the other possibilities (S or V ligatured to I). The place-name is unidentified: for the formation compare CIL xv. 4807, de fundo Buogensi; and for a preliminary discussion see Johns and Painter, op. cit., 12-13. The association of the piece with Bayeux (thus RIB) is unfounded.

85 By Paul Bidwell, who sent a rubbing and the drawing reproduced here.

86 This measure of capacity is frequent on a Dressel 20, e.g. RIB 2494.41-4. The drawing for RIB 2494.174 is incomplete, and Richmond's inverted reading SITA[…], understood as the Thracian name Sita, should now be rejected; the apparent cross-bar of A is either the tail of S in graffito (a) or ‘could be modern’ (Bidwell).

87 Paterclus ii 10a: thus identified and dated by Brenda Dickinson. She notes in her report that Paterclus ii's output at Les Martres-de-Veyre seems to have been entirely Trajanic.

88 The name Martinus is frequent among soldiers, and dec(urionis) was added for extra identification; compare another samian graffito, from Carzield: JRS xlvi (1956), 150, No. 32, [?Fl]avi sesq(uiplicari). Since the decurion commanded a troop of cavalry (turma), one of the four in a quingenary cohors equitata or sixteen in an ala, this graffito suggests that the Hadrianic garrison of Birdoswald contained cavalry, indeed that it was an ala. The size of the fort and its relationship to the Turf Wall have already suggested that it was built for an ala (E. Birley, Research on Hadrian's Wall (1961), 201), but these criteria are rejected by D.J. Breeze and B. Dobson, Hadrian's Wall (1987), 52, who, like J. Collingwood Bruce, Handbook to the Roman Wall, ed. C. Daniels (1978), 199, take Birdoswald to have been built for a milliary cohort.Google Scholar

- 2

- Cited by