The Chairman (Mr J. Taylor, F.F.A.): The Rationale for Retirement Behaviour Working Party was established in 2014. Initially, they built a model to assess a series of retirement income decisions intended to help individuals to see the potential implications on their retirement.

The model was presented and tested with members via conferences on numerous occasions. The working group also met with a number of stakeholders, including The Pensions Advisory Service, the Financial Conduct Authority and Pensions Wise, to ascertain whether there was an interest in the development of this tool to aid financial education.

Owing to the support from both IFoA members and external organisations, the working party was granted funding to complete a consumer research phase in partnership with Ipsos MORI. Following the consumer research, the model has been completely re-developed with a user interface added to provide a tool which targets individuals who may not be able to afford financial advice and are therefore more likely to be relying on a free source of information.

The working group are now currently in negotiation with the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries (IFoA) and a key external partner to look to launch the tool online later this year.

This is a very relevant topic for people in the audience. It is only 2 years since the Freedom and Choice pension changes were implemented. Over 2 years ago drawdown was available only in a very regulated, controlled format with triennial reviews, Government Actuary's Department (GAD) minima, GAD maxima, and now we have hundreds of thousands of individuals accessing drawdown, making investment decisions, income decisions, with no advice at all. At retirement the choices for individuals are very important but can be challenging to understand.

What is the best way for actuaries and the profession to support these savers?

Our first presenter, Robert Dundas, represents the Rationale for the Retirement Behaviour Working Party. Robert’s day job is leading the development and management of the Royal London investment proposition for advised customers. He is also responsible for determining the strategic asset allocation for Royal London’s popular Governed Range which had £17 billion of assets under management and around 800,000 customers as at the end of March 2017.

Robert has spent most of his career in the life company sector. Prior to specialising in the investment area, he has had a variety of roles across Defined Contribution (DC) pensions, product design, product pricing, and financial reporting.

Our second speaker is Hugh Good. He is a research director at Ipsos MORI, specialising in qualitative financial services research. Most of his work is on behalf of United Kingdom and international financial institutions, which include banks, insurers, and investment houses. He tests propositions and ideas among consumers and small business audiences.

Hugh is a member of the Market Research Society and has recently spoken at their financial services conference.

Mr R. W. B. Dundas, F.F.A.: In terms of agenda, I am going to recap on our working party objectives to give you context as to where we started. Then I am going to go into our retirement journey and cover the two games that we developed. Hugh will talk about the consumer research which was done as part of the project. Then we are going to talk about some of the next steps that we are taking and move into the questions and answers to take your contributions.

In terms of objectives, this working party was set up in 2014. This was in the era where drawdown used to be a specialist area, typically an advised sale, where the regulator typically expected consumers to have maybe £100,000 or more. In contrast, we are now in the Freedom of Choice era where drawdown is open to all, and there have been a number of stark changes.

We were primarily concerned about consumers taking decisions perhaps unaided and then running out of money. Whilst there are lots of risks the key one for us was: the consumer running out of money prematurely, and what can we do to try to help them avoid that?

We wanted to focus on non-advised customers because we felt that these customers were most at risk in the market.

We were also keen to carry out consumer research, to get a wider perspective.

In terms of our retirement journey and research, we decided to develop a model to help us to understand the financial consequences of different retirement decisions that consumers may take. We then decided to develop this model into a game which help us to perform consumer research and help consumers start to understand the impact of different decisions.

Initially, we took our first game out to various actuarial conferences for some initial testing and to gain feedback about what we produced so far and our approach.

Then we moved into the consumer research stage with Ipsos MORI which helped us to refine our game and create a second version that was much more accessible for the consumers.

We are now in the stage of seeking to work with an external partner and the aim of launching this later this year.

In terms of our first game, we decided to develop a stochastic model to underpin the game. This was intentional to reflect our skillset, and to capture the variability that was inherent in the decisions that faced consumers.

Amongst the other key ingredients we wanted were some annuity rates. We were conscious that people were quite likely to have mixed pensions provision, so we wanted to allow for that. We wanted to allow for a range of consumer decisions, and build in assumptions for mortality rate, tax, and the state pension.

We hoped to create a relatively basic model, to help make it more accessible for consumers, whilst still attempting to keep it sufficiently comprehensive to support pension decisions. However, we were also conscious that our simplifications meant that we were missing out other savings products which consumers may use during their retirement journey such as ISAs, bank accounts, houses, and defined pension benefits.

Using this approach we were trying to strike the right balance between comprehensively catching everything and having the appropriate level of simplicity to make it accessible for the end consumer.

In terms of inputs, we consciously tried to minimise the number of questions that we asked people to try to maximise usage. We were conscious that if we asked too many questions there was a high chance that people would not be interested and would not be able to complete it and therefore would not benefit from the full experience. We envisaged developing sort of web tool or app longer term.

The first two inputs we had to have were: age and pension pot. This was DC pension pot. We then wanted to ascertain how much annuity they wanted to purchase. We kept that simplistic in the sense of either nominal and index linked. Then we wanted to ask how much income they might want to take in drawdown and finally what sort of investment choice they would want to make. We simplified investment choice to using five standard risk categories ranging from cautious to balanced and then through to adventurous.

We asked for anticipated customer decisions every 10 years. Whilst we were conscious that customers could be making decisions potentially annually in a drawdown environment for the purposes of trying to “test and build”, a 10-year period was chosen. With further development, the time period could be changed to whatever was required.

We first played this out at one of the profession’s pensions conferences. We presented it and we played the game live with the audience. We put the audience into six teams. We challenged our audience to see whether they could advise a notional customer, Jo, who, just to keep it simple, had a pot of £100,000 of DC and no dependants. We challenged them to see whether they could take decisions that would allow them to beat an annuity.

That was based on the premise that annuities were receiving a lot of bad press at the time so we were interested to see if a group of actuaries could outperform an annuity in drawdown.

We also wanted to look at the behavioural side so we had some prompts which we gave to four of the six teams. We had some prompts, giving some newspaper articles at particular points in the game, which included example headline messages such as “Annuities Are Bad” press. We wanted to see whether this might alter the decision making compared to the teams that did not receive any of those prompts. We played the game with four turns’ asking the teams for income and annuity decisions times every 10 years. So for our example customer aged 60, we asked for a set of decisions at age 60, then a set of decisions at 70, and then a set of decisions at 80, and so on.

They did not know how long Jo might live in an attempt to reflect real life. This meant that the teams had to decide whether they should be taking decisions to take more income now or save their customer’s pension pot for a bit later. Is it best to have more jam today or more jam tomorrow?

In this first version of the game, we played the game live with a team of people to get each team’s decisions, type them into two computers running three games each and then play the results back live during the presentation.

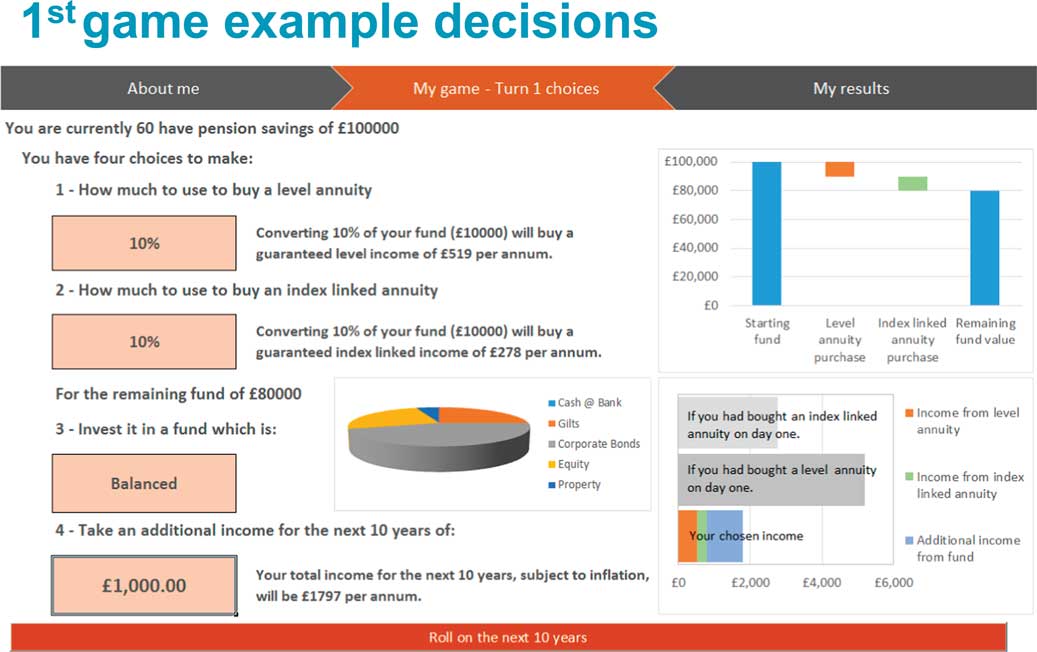

To help playback the results at each turn, we also provided some graphs to the teams to highlight how their decisions were playing out to help inform their next set of decisions (Figure 1).

Figure 1 First Retirement Game: example decisions

The chart illustrates the effect on the fund of purchasing level and index-linked annuities, the asset allocation and a comparison of the income obtained in different circumstances. In this circumstance taking 10% of the nominal annuity and 10% of an index linked annuity, then taking just £1,000 income.

In those circumstances, in the first 10 years they were taking less income than they would otherwise get if they fully purchased an annuity (Figure 2).

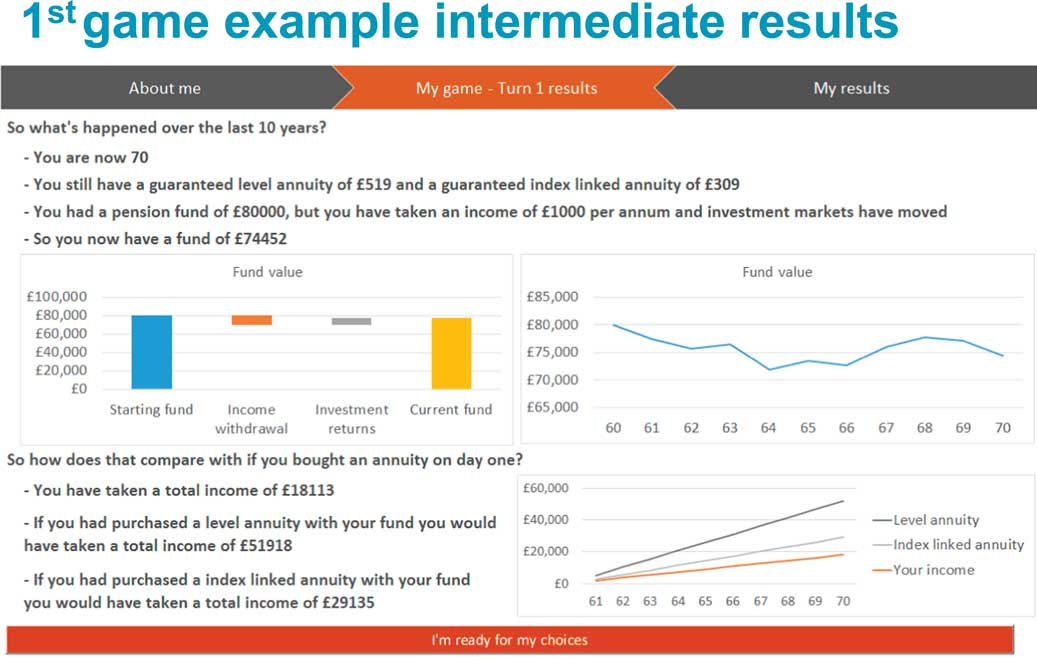

Figure 2 First Retirement Game: example intermediate results

We then had intermediate results which we handed out to all the teams. Here we were trying to illustrate how they spent the pot over the last 10 years and how their fund had performed over the years. On the bottom right you can see how the income compares to that they would have received if they had bought an annuity for comparison.

Part of the reason to reference back to the annuity was that if they could not beat an annuity, was it sensible for them to take that risk? This provided an easy initial understandable comparator on an income basis focus before considering other issues such as death benefits.

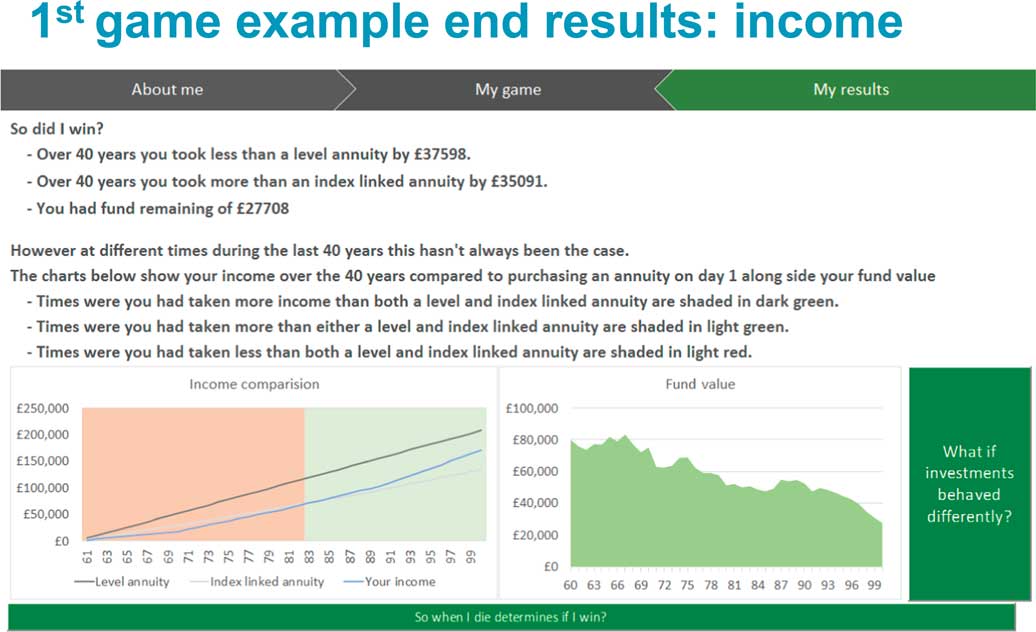

One of the other pieces we discussed was having taken all the decisions, how do you measure success for the customer? One lens that we applied was income. We played around with what were the best ways to represent this. We try to illustrate this with some colours and some charts how these choices fared across the annuity (Figure 3).

Figure 3 First Retirement Game: example end results: income

We also wanted to illustrate the death benefit lens, too. We were trying to illustrate a survival curve to illustrate that, as they get older, there is a chance that they can pass the fund value onto their family – but that the chances of that surviving reduces as they get older. That is where our first game ended (Figure 4).

Figure 4 First Retirement Game: end results: death benefits

One of the key themes of this is that we wanted people to keep playing, changing the investment or income choices and to try to increase their understanding of the potential impact of different decisions. It was hoped that consumers would be sufficiently interested to play it a number of times, to help them learn as much as possible.

We received lots of positive feedback, and were invited back to present at the regional CHIPs. However, everyone agreed that we needed to test this with consumers rather than just with actuaries.

The majority of views favoured some simplification. We were conscious of this trade-off between the desire for simplification to make it easier for consumers versus the natural desire for accuracy and detail to provide a comprehensive and complete picture. There was a conflict between the number of messages we were able reasonably to communicate to customers versus what was likely to the tipping point where we might go too far.

As John Taylor mentioned earlier, we sought funding from the IFoA and were successful. That allowed us to appoint Ipsos MORI to do some consumer research.

Mr H. Good: I will give you an overview of research, in particular qualitative and quantitative research. I am primarily a qualitative researcher, focussing on small groups of people, focus groups, and in-depth interviews.

When Robert Dundas and his team first came to us with the idea of the game, we discussed it and quite wisely, before showing the game to any consumers, we decided to gather some consumer opinion and ground ourselves in where consumers were in terms of pensions. There is a lot of research out there already, which was quite helpful.

We started off by doing some qualitative focus groups with six to eight consumers, talking to them about their baseline understanding of pensions. These were people between 55 and 65 years old and all DC pension holders. We also recruited them so that there were not any extremes. So we did not have people who knew a lot and would educate or shutdown others. They all had a low level of understanding around pensions, but that is quite typical of many consumers. We started off having some group sessions with them. Then we took those outputs and combined them with some of the publicly available research about pensions, and some of us indicated the research that Ipsos MORI does in the pension space. We took all of that and we looked at the game as it stood to see, based on that, how it might fare.

We also took some games streams into the group and gathered the people’s reaction to that. I will show you how the game iterated to give you some examples. It was fairly clear after that collision with reality to establish the level of people’s understanding and the barriers that they had around terminology, that we needed to simplify things for people to engage with us.

We took the refined game into some depth one to one interviews with consumers. We essentially took the game and walked through it with them, we walked through the screens and checked their understanding. We also checked to see what the benefits were that they were getting from the game. What were they learning? What would they take away? What was their understanding? We did that twice before we are where we are.

I will take you through some general findings from the first set of groups. Most people want to retire without worrying. They want low stressed plans and no surprises. Of all the people we spoke to, most assumed they would need to make concessions to do so: to downsize, to cut back, and they were not expecting a smooth ride in terms of pensions. Most people were underestimating how long they would live post-retirement.

People retiring today will typically live until their mid-80s. Most people either did not know or were undershooting, the consequence being that if you do not have a good sense of for how long you might live, you will under-cater financially for that.

They did have a good understanding of how the state pensions worked; typically, how much the amount is. They do not see it as the answer to all of their financial challenges. It was subsistence only; it was not holidaying and carefree lifestyles. They are genuinely aware that they need to provide for funds alongside the state pension.

Pensions are seen as a minefield and complicated. That leads to the rather aptly named ostrich effect. So when you are presented with something that is quite technical, challenging, or anxiety-inducing, you typically bury your head in the sand and do not want to think about that.

Again, from some of the wider syndicated research and the research that we did with small groups of consumers, this is the case. Also, and talking with Robert Dundas previously, banding around the “when you might die” concept maybe something which is quite common parlance among actuaries, but when you suggest or ask that question of non actuaries, it is quite confronting and challenging. It is not something they want to think about.

Also, having talked to them, they do not feel old. They do not want necessarily to accept that they are getting old. It is quite hard to engage them in some of these concepts or conversations.

They also tend to rely on the press and social circles for information in what could arguably be your second largest financial decision, aside from buying a house. People will rely on their mate who happens to know a little bit about money, or they know a friend of a friend who is a financial adviser.

Also, there is another bias at play, the salient bias; they tend to recall lots of negative things about pensions. I am generally thinking about the millions of people who retire every year in relative comfort or comfortably on pensions. Typically, the scandals and the issues they focus on because of this bias.

We did research last year when British Home Stores (BHS) had just fallen over. It was at the top of people’s minds. They were talking about the general lack of awareness, that there were provisions in place when things like that happened. Also in this audience of 55–65 that we were talking to, we were talking about the pension scandal with Robert Maxwell and the Mirror scandal. These large, scandalous events tend to be a focal point for people and they have a general mistrust in pensions and how things work.

There is also a fear of being ripped off. This audience are well aware that the sharks are circling in terms of pension freedoms, people having large amounts of money, and the risk of poor investment decision, having to be cognisant that you need to be careful about where you invest.

There is a general distrust of banks and advisory services. Although there is the term “independent” and “Independent Financial Adviser”, they genuinely do not believe it. Regardless of the fact that you have to pay for advice, they still do not believe that the adviser is not going to have some kind of scam going or some system where they can benefit from the investment decisions that they are suggesting.

Virtually no one is seen as independent in the private sector. It is a little bit better for certain consumer champion organisations like Which? or the Government comes out okay; but there is certainly a lot of mistrust.

Also, there is a desire to have pensions presented in plain English, so de-jargonising. Most people did not know what an annuity was. That is not to say that everyone did not, but a lot of people did not, or they really did not understand the difference between *****Defined Benefit (DB) and DC, and those sorts of things.

There is a challenge when talking about this to consumers to make sure that the language is as plain as possible.

The starting point, once we started the first game and the kind of key things that we were thinking about were how do you position this? Clearly there is a lot of mistrust out there so how are we going to present it and who it is provided on behalf of is going to be really important. It needs to be engaging because of the desire to bury one’s head in the sand and not think about these sorts of things. A game is a great idea to do this because it is arguably fun and interesting, and certainly designing it and using language that is accessible and is not going to alienate people and contribute to the challenge of engagement.

One of the streams of the game that we had a lot of challenges with in initial testing was one which was talking about the inheritance benefits if you died at various ages.

It is difficult sometimes to step outside of your own profession and think about what the general public might understand. A graph could be a challenge, as could the volume of information and the number of decisions that you might need to make.

After our first iteration, there was a lot of simplification, more white space, shorter sentences, a sliding bar, and interactivity throughout.

Mr Dundas: So this is your chance to get involved. I am going to give you a live demonstration of our second game.

Just to recap some of the key changes that we made was we generally simplified everything, taking account of the research that Hugh had done. There were things around making user experience much better; making it a bit more “gamified”; trying to layer our messages.

Another key decision we made was that we went from a stochastic tool to a deterministic tool. We took that decision with a relatively heavy heart. We debated this one a lot. We felt on balance we needed to keep it simpler to avoid losing the customer. Clearly, research suggests we were losing them straightaway (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Second Retirement Game: introduction

So let us now get involved. We developed this as an Excel spreadsheet. We purposely tried to design it to make it look as though it was a web tool. It was obviously intended as a prototype.

First of all, we have gone for a bright design to keep it simple. We have tried to avoid any branding. We had some buttons to illustrate. It was a prototype nature. Here we are trying to illustrate that this is independent. You are not being sold anything here. We tried to play to those values.

First of all, we have a customer. The name does not go anywhere. The first aspect was age. It turned out that using a drop-down was preferable to people typing in the date of birth. The date of birth was something which was a little personal. People did not necessarily want to reveal that. People are always uncertain about where that is going.

We can pick an age. We have the age at 65, but we can pick any age we like. We have a pot size restricted to £100,000. We will leave it there so that maybe you can do your sums a bit easier in your head.

The other key point was we wanted to introduce the area which was the progress bar. People are used to that when they are buying anything on the Internet. If you are buying something on Amazon, buying a flight or anything like that, you are used to see how far they are progressing. They do not want to start something and feel it is going to take for ever.

Mr Good: This section of the game was particularly about having people reflect on their own behaviour, and having some way of testing that out.

You can pick a persona how you think you are behaving financially and then at the end it will compare your choices and see what you are doing. People like these sorts of web-based or Facebook-based assessment tools which tell them something about themselves, like a horoscope or like personal feedback. You think you are like this, but your behaviour suggests otherwise.

Again, trying to make it more fun and more engaging rather than purely around numbers and figures.

Mr Dundas: We have these personas and used names; we are just trying to demonstrate the nature of the beast here.

The pictures had mixed feedback. Some people did not feel they were reflective or they did not like to be reminded.

Mr Dundas: Everyone likes to think that they are younger than they are. Just to clarify, we did not manage to parameterise values which impacted the retirement calculations using these pictures.

What we were trying to test here with consumers was did this feature resonate with consumers? This was playing back to the intention to encourage consumers to play the game, pick a choice, get to the end and see if their behaviour reflected what they thought, and then to try to play it again and keep playing it to understand more and more.

Moving on to the numbers, for this example we have a customer with £100,000. The first thing that we are trying to illustrate as a simple message was how much tax-free cash would they like to take, and if they were to access their pension, how much might go to the taxman.

What we discovered was that the notion of 25% tax-free cash, while it might be common knowledge to those working in the industry, was not common knowledge to the end consumer.

The first thing that we asked was how much cash would they like to take out in the form of tax-free cash.

Would anyone from the audience like to suggest and put forward a number that they think would be good for our customer? We can move the figure up and down.

£10,000.

By using a pile of coins, and by moving the scroller up and down, we wanted to use animation to help visually illustrate the customer choice.

Mr Good: It was quite an obvious thing; you pay tax on anything over 25%. Again, relatively general level of knowledge. However, this is quite a big educational point to many people having rarely seen it clearly illustrated to them.

Mr Dundas: We try to keep a similar format from one screen to the next. On the right of the screen we are trying to illustrate a kind of “Amazon shopping trolley” approach to remind them of the choices they have made.

So, the next question that we are asking here is how much annuity would they like to purchase?

You have £90,000 left in this example. Here we have the same question: what percentage of your pot remaining would you like to take?

Would anyone like to volunteer a response on what percentage of annuity they would like to purchase?

Audience: 50%.

Mr Dundas: So, we will then move onto the next screen. We are now at the point of the drawdown decision. Taking into account what they have left, how much income would they like to take? Bear in mind it is a variable income because it is in the drawdown environment.

Again, using a pile of coins, the intention here is to visually illustrate to ask the customer how much income they would like to take in drawdown.

Would anyone like to volunteer an amount?

We boiled the investment decisions down to three choices: cautious, balanced, or adventurous to keep matters simpler. We debated what it should be defaulting to. When a customer comes to it, should it be defaulted to “cautious”; should it be defaulted to “balanced”? What is the best way to approach that?

We then wanted to play back those choices. We are trying to minimise the time it took for the customer to go from an input to getting the results so that they might like to play the game again.

We used some suggested graphics to help illustrate to the consumer what sort of characteristics each choice had.

Here we illustrate the level of cash, state pension (assuming full state pension), the level of annuity taken and what drawdown income there was and how that might play out. We also provided some information boxes here so if customers clicked on them there were some basic messages. These principles could be worked up and improved in the final version.

Then we were charting what happens to the fund value to capture both the income impact and the value which might be passed on to the estate.

We then play back some of the key messages. For example, we highlight whether they paid income tax on their lump sum by taking more than 25% tax-free cash.

We wanted to encourage them to play the game again so we put in some extra buttons to jump back to an earlier screen if one of their choices was not quite what they wanted. They could then quickly change a decision and review their results again.

The other aspect we were keen to try to communicate to customers was how long they may live. As a starting point for this prototype, we used a web link to the Office for National Statistics tool shown here.

There are two inputs again: age and gender. You can then see a chart to illustrate life expectancy with some additional statistics such as the chance of reaching 100. Most customers were generally found to be unaware of this information.

Mr Good: Absolutely. It is not something that they typically would investigate or think about. Again, it is quite valuable to think about that when they are trying to plan for their retirement.

Mr Dundas: So to summarise, we wanted to customers to replay the games with different choices to help them understand some of the potential impacts of their choices. The combination of simple information and a game interface was intended to maximise the impact on the consumer.

Mr Good: I am going to focus on the final iteration and what people saw value in. People were saying that it is unique. Most people do not feel that they have seen something like this in the market previously. It does fill a gap versus documentation that is quite technical and quite dry. So, this was a valuable tool.

I am not going to read out quotes in particular but things like “it crystallises everything and puts it all in one place” are quite nice. The key educational points that people wanted to know such as “what is the tax penalty if I draw it all down?”, “How long is it going to last?”

As I have said, it addresses some of those key educational needs. Issues around tax, running out of money, and addressing some of the things that you otherwise might not think about such as “For how long might I live?” There was a lot of people thinking about these things and people facing up to these sorts of realities.

The fact that it is a game and not a dry template is really important. There is a sense that they might want to tinker with it, especially personas: “Am I this or am I that?” and replay it try to optimise their outcomes.

The fact that they are familiar with some of the user experience element, obviously it is a prototype, and it will evolve. People are used to interacting with an online environment with sliders and looking at things.

Even when reacting to the game, whom this is from is going to be important. A government body or an independent provider, or something like that will be important.

[Consumer Video Then Shown]

Mr Dundas: As part of our work we also considered what other tools were out in the market? So I will show pictures of some of the alternatives available – some of which have evolved since the pensions Freedoms and Choices came about.

Although we reviewed tools from across the market, our scope was to focus on what is available to the non-advised market, and in particular, what seems to be independent. So I am going to look at three examples available for three to consumers.

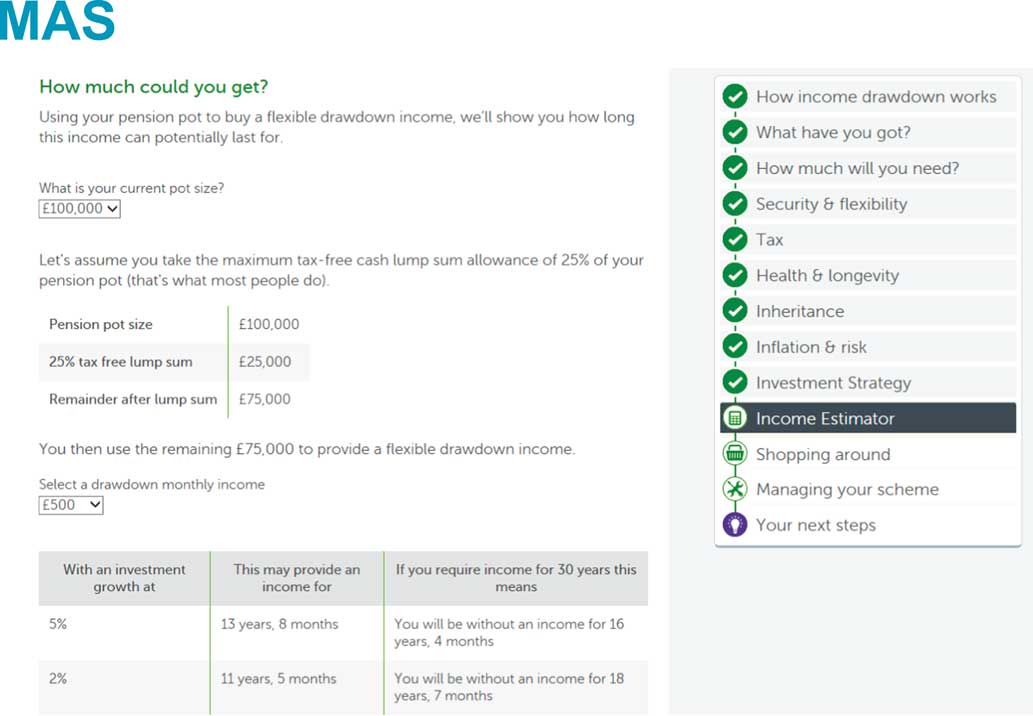

First of all, in terms of Money Advice Service, this is a screenshot of what they have on their website. There is a drop-down for what the pot size is. The customer cannot type in any number because there is a drop-down that moves in £10,000 increments (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Second Retirement Game: Money Advice Service

The first thing that they are trying to demonstrate is how much tax-free cash they can get. This is a key thing that these tools look to offer.

The next illustration is another drop-down for what monthly drawdown income they might like to take. They then provide a table underneath that to illustrate over a few different investment growth rates how long that may last.

They also provide a target of a 30-year window. In this example, the customer would spend more than half of their time without any income. Lastly, I would like to highlight the income estimate section – which is the 10th item that the customer would have reached. This means that the customer would have to go through quite a lot of information, which is useful and informative, but the customer would have to be prepared to use the tool for a relatively long time to get to this point.

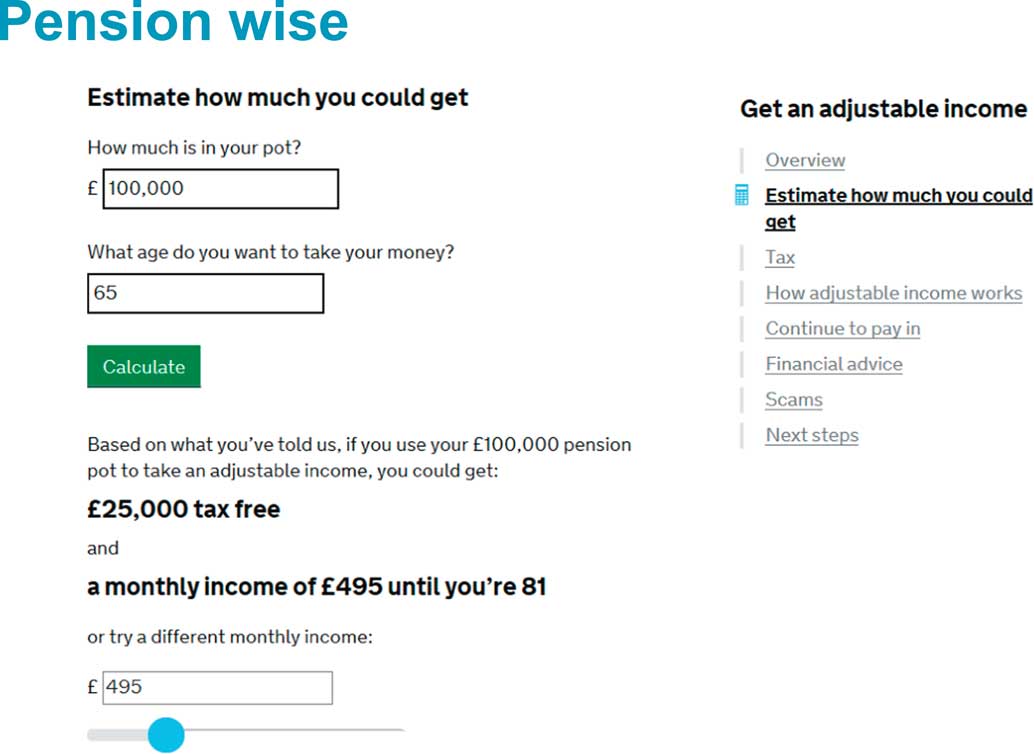

The second alternative tool was Pension Wise. This uses the same key inputs in terms of pot size and age and also illustrates how much tax-free cash they could get. There is a little bit more interactivity here because they have a slider going from left to right. You can also type a number into the monthly income (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Second Retirement Game: Pension Wise

Again, the key thing that they are trying to illustrate is for how long that might last based on a deterministic model.

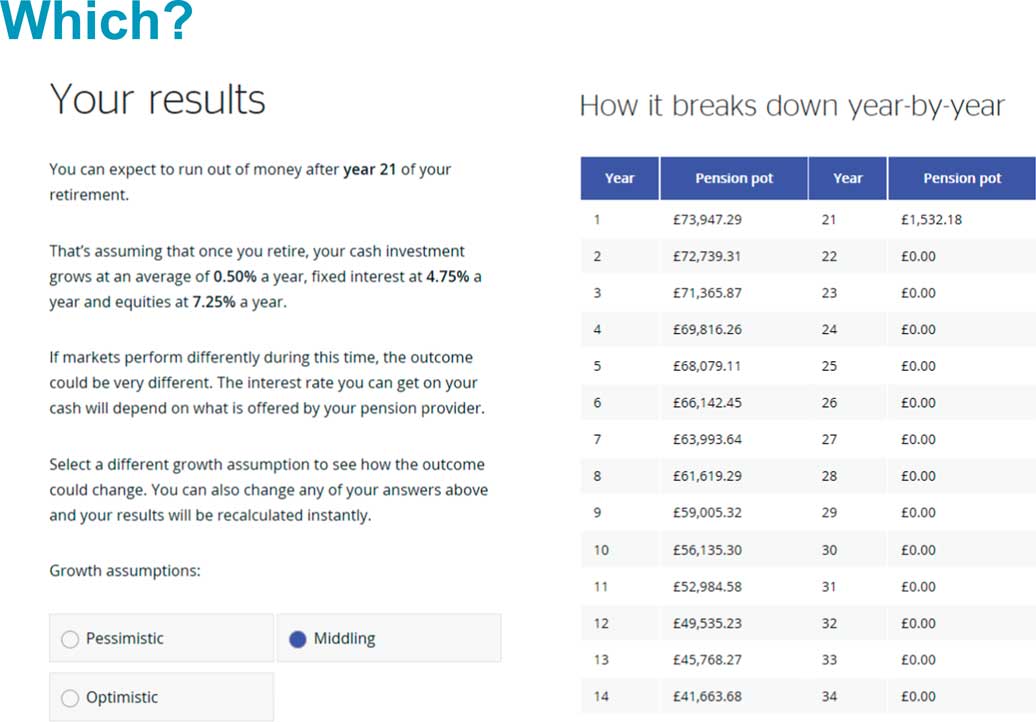

Lastly I show the tool from Which? Although it is not truly independent, a number of consumers felt it was independent in our research. The key thing that Which? offer is a table that shows annual fund values down to the penny of what their pot size might be (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Second Retirement Game: Which? Annual Fund Vales

Users can change the investment assumption and the growth rates on some of asset classes are quoted. Whilst this was interesting for us we wondered how consumers might use this information.

Over the course of our project, we have had many ideas around where we would like to develop our tool further. In general, what we are considering doing is to try to layer into our game more messages and information material, so that there is a greater depth available, but only to consumers who choose to look for more information.

We thought it would be helpful to have more consumer personas. The pictures we used in our test had limited value. It could be that a different approach using cartoons might be more appealing to customers and make it more fun which could be incorporated into the game. For example, should we have Captain Cautious, Balanced Bill, and Adventurous Andy to illustrate different personas and make it the more appealing?

We also were keen that when working with the external partner where we would try to agree that we could access anonymised consumer input data, so that over time we capture how people were using the tool. We could then use that to refine the tool and also do further research on typical choices taken.

Also, much more work could be done on the social media point of view. This can also help drive usage rates up a lot significantly too.

We have met with quite a number of partners and we are working with one in particular now to go through a due diligence process. We are looking at various approaches in terms of how to develop the game further, how we manage security, and how we do the maintenance aspects. We still need to obtain final IFoA approval. We are also keen to keep sharing research with the profession and the market.

One of the other things that is probably worth picking out is the advice risk. The profession can be quite cautious and apprehensive around people using the tool and potentially considering it as advice and potentially making ill-informed decisions or incorrect decisions. To help manage this risk, the particular partner we are working with at the moment is planning on actively managing that risk on our behalf.

Having said all that, we would like to open the session up to some questions and answers and welcome your responses.

The Chairman: Thank you, Robert and thank you Hugh. It is great to see such a very thoughtful and considered work in progress to help consumers with some of the most difficult financial challenges that they face at the moment.

While you are reflecting on questions, I will open the questions myself. If I look at the title you have used, I can reflect that a large part of the profession’s heritage has been in DB schemes where through that vehicle; we help people effectively save and manage retirement income.

Instead of DB, we have DC; instead of annuities, we now have much more in the way of drawdown. That transfer of risk is sometimes termed a democratisation of financial risk. I am not sure how people in receipt of that democracy always feel about it.

It occurs to me that, given the heritage of the profession, there is potentially an opportunity there to use the skills and the tools that we have used to help people save and decumulate their DB environment and apply them in a DC environment.

The challenge of course is whether actuaries have the skillset to communicate effectively to retail consumers. You have demonstrated a fair degree of self-awareness around that challenge earlier.

To what extent do we need to bring in expertise from behavioural economists, psychologists, and the like, to try to engage with consumers on their terms?

Second, thinking again about the actuarial skillset, could or should we be trying to invest a lot of time and effort in defaults? Instead of helping people navigate this terrible confusion of choice, give them a very sensible default that will work for most people most of the time. Is that a better or complementary way of helping people with that challenge?

Mr Dundas: In terms of other experts, I wholeheartedly agree with that point. The profession has an opportunity to work with other expertise. As a working party, we purposely did that to work with the likes of Ipsos MORI to bring in expertise that was not natural to us. That is only going to continue going forward.

In terms of the default, and potential of having some sort of industry drawdown default, for those who did not really know what to do but felt they wanted to use drawdown, that is obviously a very hot area of debate.

One of the things that we were conscious of was we were pitching this at non-advised consumers. Of the tools out there, they tended to look at matters in relative isolation. The tools tended to look at just the drawdown or just the annuity aspects rather than considering issues holistically. A key design choice of our tool, which appeared to be a relative gap in the market for the non-advised, was to bring these aspects of the cash annuity and drawdown into one place. Research showed that most consumers are going to have mixed pension provision of various sorts.

Typically, people have some element of state pension. There is going to be a reasonable chance to have some element of the final salary DB pensions but it is variable how much that is worth. Particularly in an automatic enrolment world, there is going to be a high chance that people have some element of DC.

They have a whole host of other savings. They may have a house, and ISAs and all the rest of it. We were trying to focus on particularly the DC pension aspects of cash annuity and drawdown to bring those together. We did not get as far as tackling a default solution.

Mr Good: I agree. We did have a behavioural science expert at the start of this. Their identification of what was going on, the biases, is very important. It is not rational, well-considered well-analysed choice by most people. We have lots of behavioural bias shaping from external very irrational decisions.

Looking at it through that lens, having that is part of our research in that sort of situation, the behaviour that is going on is really important.

Mr A. C. Martin, F.F.A.: May I observe that you appear to have dropped the subject of inflation between game one and two. I am not sure whether that is deliberate. It certainly would be a simplification. I would, however, be worried only illustrating flat pensions.

The solution is obviously another drop-down to take the life expectancy and ask half the population if the price of a pint of beer 30 years ago would still be sufficient today, or perhaps for another section of the population the price of milk or bread, or something.

Mr Dundas: I take that point on board and as a simplification for the second prototype tool we took out inflation for testing purposes. We agree that the final tool should also cope with inflation. We were trying to illustrate with this tool a prototype to demonstrate the benefits of what we can offer to work with another partner.

In order to develop a prototype we aimed to strike a balance between a finished product and having a sufficiently working prototype to interest other parties which then may be customised in due course.

The Chairman: Speaking to someone at the other end of the spectrum, if the tool started with “You are about to embark on retirement for 30–40 years. What do you think inflation will be in 30 years’ time?” That would probably be a bit off-putting.

Mr J. Hastings, F.F.A.: One of the things that you can do about the pension is pay more in. I wondered whether you thought this might be an instructive tool for someone in the 40–45-year range who may think that £100,000 will do them pretty well, and this might scare them into maybe thinking “It is £200,000 or more that I need to have”.

Mr Dundas: That is a good point. When we have presented this, it has been raised that we could use this to encourage people to save more. You can apply the same core engine that we have to the accumulation stage not just the decumulation stage. That fuels the debate about what age could you get people excited and interested to use this tool.

We ended up settling on let us focus for phase 1, as it were, on decumulation, then we can take it step-by-step and then move into accumulation in due course.

Perhaps it is also worth mentioning is that this is a relatively new area for the profession. We have been to quite a lot of committee meetings to get to this point as the profession is not really used to looking at this sort of thing but we are excited to help progress it. We want to take steps in a measured approach. It can make sense to try to make a success out of decumulation and then look to evolve it in the accumulation.

There is potential with working with schools, and other programs, which has been mentioned earlier in an accumulation or saving environment. It does not just have to be pensions. It could be for other things too.

Ms C. L. Kingston, F.F.A.: One of the biggest problems is looking at average life expectancy and encouraging people to think about the fact that it is not average life expectancy that they need to look at but they need to be targeting the 75% plus likelihood. That is a really difficult concept for people. Have you thought about how you might get that across?

Mr Dundas: We have experimented with the “curve of death” and we found that it was a difficult topic to manage with consumers. We tried to strike that balance between keeping consumers interested and involved and not switching them off.

I sympathise with the massive variability which is difficult to plan for given it is a kind of moving target. It is trying to communicate that if you want to go for this drawdown vehicle, then you are also essentially trying to manage towards an open goal with a massive range of variability.

This influenced us in the first game where we experimented with using an annuity comparator to drawdown. At the same time we were wary of biasing the results by pushing customers down a certain route. So it is a difficult topic to resolve.

Mr Good: I take the point on board about talking about life expectancy. It was most challenging or interesting for people when their pension might run out, that date and that age, and comparing that in their own mind. Your pension might run out here or last until here then having it alongside average life expectancy, not presenting it in isolation, might be quite useful.

Mr Dundas: The other key aspect is the nature of the customer. Does this customer have a spouse or a family? If so, there is the additional aspect of the spouse, for example, what is their combined pension? We here have just focused on the individual in this prototype and not captured what the spouse’s benefits may or may not be. So there is an opportunity to incorporate the husband and the wife’s benefits.

This is where we felt we needed to complete the work with the external partner because there were so many routes that we could resolve or explore. We felt that part of that would be influenced by the third party themselves. We were trying to demonstrate the potential and work with them to refine and launch the tool.

Mr A. H. Watson, F.F.A.: I had the fun of chairing CHIPs in Leeds where the model was demonstrated. The audience here are coming up with all the same questions that they all came up with in Leeds. We are all typical actuaries in saying: have you thought about this? Have you thought about that?

I genuinely encourage parsimony in this, as you have done. Try to avoid having so many options that people are struggling to come up with. We need simplicity. That is what the public are telling you. I genuinely encourage you to avoid listening to too many actuaries.

Mr H. R. D. Taylor, F.F.A.: I should like to congratulate the working party on doing something on the basis that doing something is always better than doing nothing.

First of all, innovation is a great thing, but it is always about testing and learning. It is good to see that you are at the early stages of the journey. I do not think that we are even halfway there. This is just the start, but there are many things to be learned from it. So that is a huge positive.

My second point is that it seems to me that institutionally, the UK financial services industry is very slow to respond to change. The wheels grind very slowly. Everyone is naturally very cautious, very risk averse, but sometimes by not taking action you can generate risks. Sometimes it is better to do things even if they are a bit risky, than create huge, systemic risks, so slow to respond can be dangerous. I am not quite sure what needs to be done to make that accelerate.

My third point is about systemic risk. We are sitting at the moment in the middle of a huge systemic risk in the switch from DB to DC, particularly with the increasing trend of assets to be transferred from people’s DB holdings into the DC environment even though there is some advice and DB analysis in place. There are unprecedented levels of transfer from DB schemes into SIPPs. There is the potential for the mass market in DB schemes to come a cropper with transfers into DC. No one really understands what is happening there. Systemic risk is a real and present danger.

My fourth point is about range of tools. We are looking at one tool here. There are other tools out there. The eventual answer that will emerge over the next few years will be a whole range of tools of different styles, and different consumers will latch on to different styles. I do not think that it will be a case of one size fits all.

Also, within the tools there needs to be better layering. One of the ways of creating simplification is by layering and by tailoring it according to what the area of focus is of the consumer using the tool. There is probably a lot to be learnt from not just behavioural researchers but the companies who specialise in all of this; Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and such like, around the world. Also, there is a potential role for Silicon Valley. The range of tools is something that needs to be encouraged and developed.

My final point is that we have had another prototype brought to the fore a few weeks ago. It is being rolled out for public view over the next few weeks. That is Pensions Dashboard, which is something that will attract a lot of attention. It seems to me that by piggybacking on that it will be interesting to see in what ways Pensions Dashboard, which will have a lot of money and promotion put behind it, could be linked into this initiative.

Again, Pensions Dashboard should be completely agnostic and independent. So, if this is positioning itself in the same way this is perhaps an opportunity.

Mr Dundas: Thank you for those points. In particular I would pick out your point around not taking any action has been raised before. In some venues that was described as a ticking time bomb.

If the profession does not stand up and do something in this area, then potentially there could be a scandal if things go wrong and the profession was found wanting. There are concerns, as you have mentioned, around DB transfers. How is that going to pan out? Is that going to be a good outcome for consumers or not?

In terms of the independence aspect, we have been really cognisant of that. We want to leverage the independence of the actuarial profession and not attach ourselves with any commercial operation. There is no fund bias or product bias within the tool. We are really keen to do that. Trying to piggyback into some government agencies or government initiatives, as you suggest, is possibly the best way to go to leverage that benefit.

Mr Good: I would say on the layering point there are always some consumers that want more things to play around with and make it more accurate or to fiddle around with inflation or tax, or things like that. The layering point, having greater flexibility or things that you could change behind the dashboard if you want to, would cater for a broader range of people. But absolutely it is important to keep it very simple for the public. If you do not want that, then that detail is going to put your customers off.

Mr J. E. Gill, F.F.A.: I echo Harry Taylor’s comments in thanking the working party, but I do question whether this is what the profession should be doing.

I am part of an organisation which has spent quite a considerable amount of money building something similar. I am not sure that the profession has quite the same amount of money. As a result, I suspect that the profession’s role could be better defined in terms of standard setting or being an appropriate critical mechanism around these tools.

We are all in complete agreement regarding the need for these kinds of tools. It is essential. My suggestion to you would be that the profession perhaps would be better served in carving out a different role as a standard setter or a critical friend rather than a developer.

Mr Dundas: Thank you for your thoughts. In our discussions with our external partner they are very much looking to take on ownership of the development. That has been ideal for us because it has meant they can rely on the experts that they are used to dealing with to develop these tools, and the profession is not having to develop business cases to spend a lot of money, as you say, in an area which may not be most valuable for it.

If our discussions with our partner are successful, then it will not be a big cost for the profession.

Mr R. K. Sloan, F.F.A.: The key point that has come out from one or two of the earlier contributions has been the advice risk that you mentioned before. It is a very dangerous tool. I agree that something needs to be offered. The Government should require a pensions test, and you would have to show a certificate that you have taken advice from somebody.

It is a minefield. I applaud you for at least trying to help find a way through it.

You mentioned tax. The pensions top up: what a swindle that was! The benefit is entirely taxed. You put your tax-free money in and it is all taxed. What happened to the capital content that we used to have in our annuities?

The drawbacks of this simplified approach are things like a very important contract is an investment linked annuity. I used those a lot when I was advising clients into retirement. They might like the investment idea; they do not know how long they are going to live. Actuaries, if nothing else, should at least put the longevity guarantee into as much of the mix as they can. Certainly, I do not want to think I am going to be 100% alive one day and nought percent alive the next day. Ensuring longevity should be built into most of these contracts, but I do not think it is nowadays. There are very few available.

There are other things: the spouse’s pension; guarantee periods. I have mentioned before that you can have a 10-year guarantee with spouse’s pension with overlap and you cannot lose, by and large. A lot of people do not like annuities and say “they take all our money” but you can build in all these features but not with a one size fits all tool like this.

It has some uses to whet the appetite, but I would like to see something pointing people to taking advice from a properly qualified professional before pressing any buttons and putting any money in.

Mr Dundas: Thank you. This trade-off between simplification and managing all the complications of choice out there was something that we grappled with over the entire journey.

In terms of the product range that you mentioned, we were simplifying it back to what is typically available to a non-advised customer, so it represents those choices. We could bring things in like guarantee periods and spouse benefits into the annuity choice with relative ease.

We were trying to show you the test and learn approach with a prototype. We have a much more complicated model in the background that we can use. You can almost pick it off using a menu approach that we can experiment with further consumer testing to see what works and what does not work.

Mr C. Taylor, F.I.A.: Internet access, mainly mobile, means some of your screen shots will need to look slightly different for the user experience.

I love the fact that we are helping people. I admire it and I really like the approach you are taking with customer feedback, developing personas and getting people to test it.

I have a question for the profession in terms of the commercial conflict that has been raised. You are competing with insurance companies and consultancies. It feels that way. They fund the IFoA. It is not just the risks. If you are going to pass it on to somebody else, there is the commerciality with that as well.

Mr Dundas: That is a fair point to raise. In discussing this with people, sometimes it has been raised that maybe we should charge for this service and it perhaps should be approached in that fashion and that there is another competitor in the field, and that is the actuarial profession. That approach has not always attracted so much merit or support at committee meetings.

It is a difficult project to land. As we discussed, we are trying to do something and we are trying to put our best foot forward. We are keen to use this approach and to keep evolving this as an initial prototype.

The Chairman: It remains for me only to acknowledge the contribution from Robert Dundas and Hugh Good in the run-up to this event. Given the great work that the profession does to help consumers, either through DB schemes again, or life offices, and Solvency II, this is one massive area where consumers need a lot of help and the spirit of doing something, as we are exhorted to do, is very valuable.

Quite what the destination will be for the profession is, whether it will end up being standard setting or providing these tools, I do not know. The insight that you are generating for this can only help inform that outcome.

Please join me in thanking Robert Dundas and Hugh Good for a wonderful presentation.