Do political parties respond to interest group mobilization? Both, political parties and interest groups are important intermediary organizations that transmit societal interests to political institutions.Footnote 1 While political parties however compete at elections to take over governmental responsibility, interest groups are particularistic organizations that seek to shape policy making indirectly through lobbying decision makers. Given the important role that political parties play in determining policy outcomes,Footnote 2 political parties are highly attractive targets for interest groups seeking to influence policy making in their favour. Despite the important role that parties and interest groups play in Western democracies, it is however largely unknown how interest groups shape the policy agenda of political parties. In this article, I seek to close this important gap in the literature by shedding light on whether political parties respond to interest group mobilization.

The literature on party competition has devoted considerable attention to the question how political parties choose the policy issues they emphasize. There are effectively three lines of research that have sought to explain the issue agenda of political parties: the issue ownership theory, the riding the wave approach and research investigating the interaction between different political parties in a party system. In what follows, I will briefly discuss these approaches before discussing the few studies that shed light on the link between parties and interest groups. The issue ownership theory suggests that political parties ‘own’ certain policy issues.Footnote 3 For instance, social democratic parties are considered to be particularly competent when it comes to social welfare while voters trust Green parties most when it comes to the environment. According to the issue ownership theory, parties selectively highlight their own policy issues to increase the salience of these issues among voters to turn the election into a contest on their favourable issues.Footnote 4 Since voters would evaluate political parties with regard to their competence on policy issues that are important to them at the time of the election, strategically emphasizing owned issues can help parties to reap electoral gains.Footnote 5

The riding the wave theory by contrast suggests that selective issue emphasis is not a top-down process in which parties seek to influence their constituents, but that it is instead a bottom-up process in which political parties take their cues from voters by responding to their issue priorities.Footnote 6 According to this view on party competition, parties can reap electoral gains by emphasizing policy issues that are deemed important by voters as this would signal responsiveness. Rather than seeming out of touch, taking up the issues that are salient to their electorate would allow parties to give voters the impression that they take citizens’ concerns seriously. Recent empirical evidence has accordingly shown that political parties respond to the issue priorities of voters by taking up salient issues in their election manifestosFootnote 7 and in their daily press communication.Footnote 8

Another line of research has argued that the attention that parties pay to policy issues can be explained by the interaction between different parties in a party system.Footnote 9 A prominent argument suggests that political parties that are in a disadvantaged position would strategically use selective issue emphasis to reshuffle the dominant lines of party competition in their favour.Footnote 10 In a recent contribution, Hobolt and de Vries have for instance introduced the term ‘issue entrepreneurs’ for parties which strategically highlight a previously ignored policy issue and take a position on that issue that is substantially different from the position of their competitors.Footnote 11 Meguid has by contrast focused on the interaction between niche parties and mainstream parties and showed that the decision of mainstream parties to emphasize or de-emphasize an issue is importantly driven by the existence of niche parties which primarily campaign on the issue.Footnote 12 Green-Pedersen and Mortensen moreover demonstrated that the interaction between government and opposition parties is important to understand parties’ issue emphasis.Footnote 13 They showed that opposition parties enjoy much more flexibility and can freely challenge incumbent parties on their favourable issues while government parties are driven by the issue agenda of the opposition. Finally, Green-Pedersen and Mortensen pointed out that the common issue agenda in a party system is an important factor that accounts for why political parties pay attention to an issue.Footnote 14

While these studies have shed important light on why political parties choose to emphasize a certain issue, the impact of interest groups on parties’ issue agendas has been entirely ignored up until now. In fact, the relationship between parties and interest groups has generally received only very little attention to date.Footnote 15 Most studies examining party–interest group relationships focus on the interaction between specific parties and selected interest groups,Footnote 16 they study the general organizational ties and collaboration patterns between parties and interest groups in one or just a few selected countriesFootnote 17 or they study party–interest group relationships at the European Union level.Footnote 18 Even though these studies have made an important contribution by mapping the general party–interest group interaction patterns or studying the ideological alignment of parties and interest groups, there is up until now no study that investigates how the issue agenda of political parties is shaped by interest groups.

Studying how interest groups influence the policy agenda of political parties is important for our understanding of political representation. Political parties play a crucial role for political representation in Europe. They aggregate and articulate voter preferences and are key actors in the formation and the maintenance of governments in parliamentary systems. Political parties are therefore important intermediary organizations that link voters with political decision making. It is however crucial for political representation that parties are responsive to voter demands so that there is congruence between what voters want and what political parties do.Footnote 19 Given that every day thousands of lobbyists around the world approach political parties in an effort to influence party policy in their favour, it is important to understand to what extent parties respond to interest groups and not to their own voters. If interest groups manage to influence party policy at the expense of voters, democratic representation is seriously undermined by lobbying, as not all societal interests have an equal chance to mobilize and to fight for their cause.Footnote 20

In this article, I therefore seek to address this important gap in the literature by studying how interest groups shape the policy agenda of parties. I argue that political parties respond to interest group mobilization as lobbyists offer valuable information, electoral support and attractive personal rewards. Political parties therefore have strong incentives to take up the policy issues prioritized by interest groups on their policy agenda. However, since political parties need to satisfy voter demands to secure their re-election, interest groups are particularly able to shape the policy agenda of political parties when they prioritize policy issues that are also important to their voters. The theoretical expectations are tested based on a novel empirical analysis that combines an unprecedented longitudinal dataset on interest group mobilization with data on parties’ issue emphasis in election manifestos obtained from the Manifestos ProjectFootnote 21 and data on voters’ issue priorities gathered from public opinion surveys. On the basis of a comprehensive empirical analysis studying the responsiveness of five major German parties in seven elections from 1987 until 2009, this article demonstrates that parties adjust their policy agendas in response to interest group mobilization and voter demands and that interest groups are more successful in shaping party policy when their priorities coincide with those of the electorate.

The article proceeds as follows. In the next section, the theoretical argument is explained in detail and hypotheses are formulated that guide the subsequent empirical analysis. Afterwards, the research design of this study is illustrated before the results of the empirical analysis are presented in the ensuing section. The article concludes with a summary of the findings and a discussion of the implications for political representation in Western democracies.

POLITICAL PARTIES, VOTERS AND INTEREST GROUPS

Parties are conceptualized as rational, goal-oriented and purposeful collective actors. Following the party behaviour model set out by Riker, I assume that parties are primarily office-seeking actors.Footnote 22 I hereby make no assumptions about whether parties intrinsically value executive offices or whether offices are only an instrument to ultimately influence policies. Parties may pursue ministerial portfolios for the intrinsic benefits that come with executive posts such as power, prestige or personal rewards. At the same time, parties may however also strive to take over governmental offices as a means to shape public policy.Footnote 23 Such instrumental office-seeking is ultimately driven by policy goals and parties only seek to obtain control over executive offices as these allow them to influence policy decisions in the respective ministerial jurisdictions.Footnote 24 Whatever the underlying motivation for their office-seeking behaviour may be, office-seeking parties seek to win elections in order to obtain control of the executive branch or as much of it as possible.

Every day thousands of lobbyists approach political parties in capitals around the world to shape policy making in their favour. Why should parties respond to interest group mobilization by devoting attention to these issues? Drawing on resource exchange theory developed in interest group research,Footnote 25 I conceptualize the interaction between parties and interest groups as an exchange relationship in which interdependent actors trade goods with each other. With regard to interest groups, I assume that they primarily seek to influence public policy. Given that political parties are the key decision makers that shape policy outcomes in particular in parliamentary democracies,Footnote 26 interest groups have important incentives to put their issues on the policy agenda of parties. With regard to political parties, I suggest that interest groups supply four goods which are valuable to parties: information, campaign contributions, the electoral support of their members and personal rewards.Footnote 27 By supplying these goods, interest groups can ask parties to return the favour by devoting attention to issues which are important to them.

First, political parties seek to take over governmental offices and are therefore expected to have a comprehensive policy programme in which they set out their agenda for all major policy issues. In the parliamentary arena, parties are moreover confronted with a multitude of often very technical and complex policy proposals on which they have to make up their mind. Given that political parties are typically only moderately staffed, they often lack sufficient expertise to develop policy solutions on all these policy issues. By contrast, interest groups are particularistic organizations that are only active in a small and circumscribed policy sector. They are in close contact with their members and are well-informed about the specificities of their particular policy niche. As a result, interest groups are specialists in their domain which can offer highly valuable information to parties.Footnote 28 Interest groups are therefore welcome interlocutors for political parties and their parliamentary representatives which are constantly in need of external expertise.

Second, another important good that interest groups offer to office-seeking political parties are campaign contributions.Footnote 29 Elections are a costly enterprise for political parties. Running an election campaign requires hiring a campaign team, designing and printing millions of posters and flyers, producing television and radio ads and buying air time on the major TV and radio channels. As a result, running a successful electoral race requires spending several millions on campaign expenses.Footnote 30 For instance, during the 2009 election campaign in the run-up to the general national election in Germany, the campaign expenses amounted to €88 million for the Christian democratic CDU, to €85 million for the social democratic SPD, to €26 million for the liberal FDP, to €16 million for the Green Party and to €14 million for the socialist Left party.Footnote 31 Interest groups constitute an important source of campaign funding which regularly donate large sums to political parties. For instance, in the Bundestag election year 2013, the German FDP raised donations of about €10.9 million compared to income from member contributions of about €6.6 million and state funding of €10.5 million.Footnote 32 Hence, political parties seeking to obtain control over executive offices have great incentives to listen to interest groups as they are important providers of campaign contributions which are desperately needed to run a successful election campaign.

Third, interest groups are attractive to political parties as they can mobilize their members to vote for a specific party at the polls. Interest groups are intermediary organizations that represent the interests of their members or supporters before government. For instance, trade unions are membership organizations that bring together employees in a specific economic sector. Similarly, the German farmers’ association represents the interests of about 300,000 farmers and their families.Footnote 33 When a political party promotes policies that are not in line with the policy goals of an interest group, that interest group can threaten the party to instruct its members not to support the party at the next election. Electoral mobilization is an important strategy in the lobbying toolbox of interest groups. During election campaigns, interest groups for instance often question political parties about their stances towards selected policy issues (so-called ‘election touchstones’) to provide their supporters with indirect vote recommendations. The German Confederation of Trade Unions, currently representing about eight million German citizens, has for instance used such a recommendation to mobilize electoral support for the SPD since the 1950s.Footnote 34 Office-seeking political parties therefore carefully listen to interest groups when drafting their election manifestos to make sure not to lose the support of their members at the polls.

Finally, interest groups provide important personal incentives to party leaders. On the one hand, listening to interest groups and establishing good relationships with lobbyists is attractive for party leaders in order to secure a career after leaving politics. Leading politicians frequently take up a lucrative position in an interest group after the end of their political career. Two recent examples from German politics illustrate that phenomenon. Steffen Kampeter (CDU), who was a Member of the German Bundestag from 1990 until 2016 and state secretary in the German Finance Ministry from 2009 until 2015, became Executive Director of the Confederation of German Employers’ Associations (BDA) in 2016. Similarly, Jan Mücke, who was a Member of the German Bundestag for the liberal FDP from 2005 until 2013 and state secretary in the Ministry of Transport, Construction and Urban Development from 2009 and 2013, became Executive Director of the German Cigarette Association in 2014. On the other hand, interest groups also provide important personal rewards for party leaders during their time of office by offering lucrative seats on advisory boards, side payments or by inviting politicians on expensive business trips. Recent studies accordingly show that former MPs obtain significantly higher wages after office.Footnote 35 Given that party elites play an important role in the drafting of election manifestos,Footnote 36 it is a promising strategy for interest groups to offer personal rewards to party leaders in order to make sure that their policy issues make it to the policy agenda of political parties.

In conclusion, I have argued that interest groups seek to influence the policy agenda of political parties. Political parties in turn have important incentives to respond to interest group demands by taking up their issues as they offer valuable information, campaign contributions, electoral support and also personal rewards to party leaders. I therefore expect that interest groups affect which policy issues are emphasized by political parties. More specifically, I hypothesize that the emphasis that parties place on policy issues importantly increases with the mobilization of interest groups on these issues. A higher level of lobbying activity of interest groups on a given policy issue results in a higher level of attention to this issue by political parties.

HYPOTHESIS 1: The attention that political parties pay to policy issues increases with interest group mobilization on these issues.

To win office, parties also need to attract voters. Citizens can be regarded as principals who temporarily delegate the power to make public policies to political parties who act as their agents.Footnote 37 In order to sustain the support of their constituents, political parties should make policies that are in line with the desires of their electorate.Footnote 38 Importantly, voters can punish political parties for not acting in their interests by supporting another party in the next election. Political parties therefore have strong incentives to satisfy the demands of their voters to maximize their vote share in order to obtain control over executive offices.

Ansolabehere and Iyengar accordingly suggested that parties ‘ride the wave of public opinion’ by highlighting policy issues which are salient in the minds of citizens.Footnote 39 According to that perspective, parties constantly monitor public opinion and respond to the issue priorities of voters to reap electoral gains by signalling responsiveness to their electorate. In line with that view, recent empirical evidence shows that political parties carefully listen to the concerns of citizens and prioritize policy issues which voters deem important.Footnote 40

Since parties are dependent on the electoral support of voters, I expect that the effect of interest group mobilization is conditioned by the salience of issues among voters that supported a particular party. Interest groups should find it particularly easy to put their issues on the agenda of political parties if party supporters similarly consider these issues as important. However, if party supporters have issue priorities that are entirely different from those of interest groups, lobbyists should struggle to align parties with their issue agenda as parties need to satisfy voter demands to secure their re-election. Thus, I expect that parties adjust their policy agendas in response to interest group mobilization, but that interest groups are more successful in shaping party policy when their issue priorities coincide with those of a party’s electorate.

HYPOTHESIS 2: The effect of interest group mobilization on parties’ issue attention increases with the attention that party supporters pay to these issues.

RESEARCH DESIGN

In the following, I explain how the dataset was constructed on the basis of which my theoretical argument is tested. First, I discuss the case selection before the operationalization of the dependent variable is illustrated. Afterwards, the measurement of the explanatory and the control variables is discussed.

Case Selection

In order to study the effect of interest group mobilization on parties’ policy agendas, I have selected Germany for the analysis as Germany is the only country in the world with an obligatory interest group register since the 1970s. This annually maps interest group mobilization up until today. In 1972, the Bundestag passed a law which obliges all interest groups that seek contacts with members and parties in the Bundestag to enrol in a lobbying register. The first register was published in 1974 and it is updated annually so that interest group mobilization at the Bundestag can be mapped on an annual basis. The lobbying register is an ideal data source to measure the mobilization of interest groups. According to the rules of the Bundestag, interest groups can only participate in hearings and obtain a pass to enter the Bundestag if they are officially registered.Footnote 41 Drawing on the Bundestag register allows us to measure the mobilization of interest groups where they come into contact with the political parties in the Bundestag, while excluding organizations which primarily offer services to their members or which are only politically active at the regional or local level. I will make use of this unique dataset to study the effect of interest group mobilization on parties’ issue agendas from 1987 until 2009.Footnote 42

Dependent Variable

In order to measure parties’ issue attention, I rely on parties’ election manifestos. Parties regularly draft manifestos and lay out their stance on different policy issues to signal their policy commitments to voters. Election manifestos are the most encyclopedic statements of parties’ policy agendas on which basis parties compete for voters. As research on political parties and legislative politics has shown, these policy platforms importantly structure the behaviour of political parties in parliament and in government. First, parties strive to enact their policy platforms after the election in order to avoid electoral punishment for not keeping their promises at the next election.Footnote 43 Hence, pledges made in election manifestos are frequently enacted by parties in the parliamentary arena. Second, election manifestos serve as a basis for coalition bargaining in which ministerial offices and the policy agenda of the coalition cabinet are negotiated.Footnote 44 Finally, election manifestos can be used to ensure intra-party agreement.Footnote 45

Thus, election manifestos are by no means just ‘cheap talk’ and interest groups therefore want to make sure that parties emphasize policy issues that are important to them in their manifestos. Accordingly, the spokesperson of the German Confederation of Trade Unions (DGB) explained that acting early to influence the content of parties’ 2013 election manifestos was an important lobbying strategy to successfully put their issues on the political agenda. He commented that

the DGB has already adopted a position paper in 2012 which was forwarded to all political parties. … If we formulate our position and transmit our views to political parties so early, we have better chances that parties take up our issues in their election manifestos. We were successful with this strategy regarding the minimum wage, temporary employment and contracted work.Footnote 46

Thus, election manifestos constitute a rich data source that has been used by a wide variety of scholars to measure the attention that parties pay to policy issues as well as their policy positions.Footnote 47 I rely on data provided by the Manifestos Project (MP) which has used content analysis to code the content of parties’ election platforms.Footnote 48 The MP has generated the most comprehensive and most widely used dataset on parties’ policy priorities to date. Human coders have divided election manifestos into units of analysis (so-called ‘quasi-sentences’) and have allocated these quasi-sentences to policy categories specified a priori in a codebook. The attention that political parties pay to policy issues is measured by taking the percentage of quasi-sentences devoted to a certain issue area. Given that drafting election manifestos is a lengthy process which typically takes several months if not years,Footnote 49 I expect that there is a lagged effect of interest group mobilization as parties need time to process interest group demands.

Explanatory Variables

In order to study the effect of interest group mobilization on the emphasis that parties place on policy issues, I rely on a novel dataset that allows for tracing the mobilization of interest groups over a period of forty years, the lobbying register of the German Bundestag. As mentioned above, the lobbying register annually maps all interest groups that seek to lobby the German Bundestag. All interest groups that seek to gain access to the Bundestag or its members and their staff need to provide information about their areas of interest, their members, their leadership structure, their affiliated organizations and their contact details.Footnote 50 Interest groups can only enter the Bundestag and participate in hearings or consultations if they are officially registered. Unfortunately, the lobbying register has not been available as an electronic database, but the Bundestag merely published the annual lists in the Bundesanzeiger which is a publication of the German Ministry of Justice. Thus, it was a major data collection exercise to collect all the annual lobby lists, to convert the lists into an electronic dataset and to code the interest groups according to a number of relevant characteristics. As a result, the Bundestag lobbying register has so far not been used for any longitudinal analysis. It however has to be noted that a few recent studies have relied on one yearly release of the register for a cross-sectional map of the German interest group population.Footnote 51

Based on this register, I operationalize interest group mobilization by the relative number of interest groups that lobby the Bundestag in a given policy domain. To construct this measure, all interest groups that were indicated in the lobbying register were classified into issue areas according to the Policy Agendas Topic Codebook. The Topic Codebook was developed by the US Policy Agendas Project which maps the policy agenda in the US by manually coding policy documents into policy areas.Footnote 52 The Topic Codebook classifies policy documents into nineteen major issue areas and 225 subissues. I relied on a revised version of the codebook designed by Breunig which takes into account the specificities of the German political system and I moreover slightly adjusted that codebook for interest group data by adding a few additional subissues.Footnote 53 Human coders classified interest groups into policy areas based on information about their interests and activities that interest group provide in the lobbying register and by additionally relying on information retrieved from interest group websites and from phone calls with interest groups. Reliability tests indicate high levels of correspondence between different coders.Footnote 54 In order to shed light on the effect of interest group mobilization on the emphasis that political parties place on different policy issues, the policy categories of the Manifestos Project and the Policy Agendas Project have been matched (see table A.2 in the Appendix). Overall, eleven common issue areas could be identified for which the policy categories of the Manifestos Project could be unambiguously matched with the policy categories of the Policy Agendas Project. These issue areas include welfare, decentralization, education, defence, European Union, immigration, environment, agriculture, civil rights, culture as well as technology and infrastructure.

To measure the issue attention of party supporters, I rely on the Politbarometer which is a representative monthly public opinion poll conducted in Germany.Footnote 55 More specifically, voter issue attention is operationalized by the so-called most important problem (MIP) question that is included in the Politbarometer since 1986. The most important problem question is an open question that asks respondents to report the most important policy issue at the time when the survey is conducted. It is a standard tool in the study of political parties, public opinion and government responsiveness to measure the issue priorities of voters.Footnote 56 To match the policy priorities of citizens with the interest group mobilization and the Manifestos Project dataset, the problems named by survey respondents were similarly classified into the eleven common issue areas (see table A.2 in the Appendix). I then measured voter issue attention by the relative number of respondents that indicated an issue area as most important.

Since parties should be most responsive to voters that actually supported them at the polls,Footnote 57 I rely on the issue attention of party supporters by taking the percentage of respondents who have voted for a given party that consider a policy issue as most important. In order to operationalize the issue priorities of party supporters, I combine the most important problem question with a question that asks respondents to indicate which party they have voted for in the last election. However, in order to test whether the results hold when the issue priorities of the entire electorate are taken into account, I estimated an additional model specification in which I measure the issue attention of all voters by taking the percentage of all survey respondents that deemed a policy issue as most important for them. The results are substantially the same (see table A.3 in the Appendix).

Since parties need time to draft their manifestos and to process interest group and voter demands, I rely on the lagged interest group mobilization and voters’ issue salience. More precisely, party issue attention at the current election t −0 is predicted by interest group mobilization and party supporters’ issue attention in the year prior to a given election t −1. In order to check the robustness of the findings, I have also estimated alternative model specifications in which I used the current interest group mobilization and issue priorities of voters in the year of the election as well as the average values across the entire legislative term. The results are by and large the same (see table A.4 and table A.5 in the Appendix).Footnote 58

One may argue that interest group mobilization and party supporters’ issue priorities are correlated as interest groups and voters may simply care about the same policy issues. However, the Pearson correlation coefficient only amounts to 0.16, thus indicating a relatively low correlation between the two variables. In addition, as one may suggest that the salience of issues to voters in the previous period may affect the level of interest group mobilization in the current period, I have estimated an additional model specification in which I include both voter issue attention at t −1 and voter issue attention at t −2 in the regression model to shed light on such a potential relationship between the two variables (see table A.6 in the Appendix). The effect of interest group mobilization at t −1 on parties’ issue emphasis at t −0 remains constant irrespective of additionally including voters’ issue priorities at t −2, thus providing further evidence that interest group lobbying indeed has an independent effect on parties’ issue attention.

Control Variables

In order to shed light on the effect of interest groups on parties’ issue attention, the following control variables are included in the analysis as they might potentially affect the hypothesized relationship. First, I control for party size as large parties typically behave as catch-all parties that flexibly adjust their policy profile to ‘catch’ as many voters as possible.Footnote 59 As a result, it is expected that larger parties should have a more diverse issue agenda than smaller parties which often concentrate on few policy issues. Party size is measured by relying on the vote share of the party in the previous national election.

Second, to empirically evaluate the hypothesized effects, a measure for the policy extremism of political parties is included in the model, as more ideologically extreme parties are more policy-focused and often concentrate on a more narrow issue agenda than moderate mainstream parties.Footnote 60 The policy extremism of parties is operationalized by the absolute value of the left-right position of political parties obtained from the Manifestos Project.Footnote 61 The left-right positions are operationalized using the proportional scale suggested by Budge by subtracting the percentage of left quasi-sentences from the percentage of right quasi-sentences coded by the MP.Footnote 62

Third, I control for the government status of political parties. When political parties enter executive offices, they have to deal with a variety of different policy issues that need to be regulated. Irrespective of their own issue priorities, government parties have to fill all ministerial portfolios in a country and are responsible for producing and implementing legislation across the entire spectrum of public policies. As a result, I expect that the issue agenda of government parties is more diverse than the issue agenda of opposition parties which can concentrate on their preferred and most favourable policy issues.

Fourth, previous research has shown that parties’ issue emphasis is importantly influenced by the attention that rival parties in a party system pay to different policy issues.Footnote 63 Accordingly, I control for the party system issue attention by including a variable that measures the lagged average issue salience for all parties in a party system. In line with previous research, I expect that the lagged party system-wide issue attention has a positive effect on the attention that a party pays to a policy issue.

Fifth, given that the responsiveness of parties to interest group mobilization may vary with the state of the economy,Footnote 64 I control for the unemployment rate in the regression model. If the unemployment rate increases, parties may focus primarily on economic issues while downplaying other issues so that the issue agenda narrows down. The data were obtained from the German Federal Employment Agency. Sixth, since German reunification has fundamentally altered Germany’s economy, its political system and also its party system, I include a structural break control to capture this external shock. This variable is coded 0 before German reunification and 1 afterwards. I expect the issue agenda to be more concentrated after unification as a few issues have suddenly become very salient while other issues have lost in importance.

Finally, I control for government spending in an issue area. Given that government activity affects the salience of issues among voters and the mobilization of interest groups,Footnote 65 it is important to control for this variable to avoid any spurious correlation. I expect that government spending on an issue is positively correlated with the emphasis that parties place on an issue.Footnote 66 I used data on public expenditure to operationalize government activity in different issue areas, which is a standard indicator for government attention in the literature.Footnote 67 Data on government spending were obtained from the German Federal Ministry of Finance. These data cover all public expenditures at the federal level which are directly controlled by the German federal government. Descriptive statistics of all variables included in the empirical analysis can be obtained from table A.1 in the Appendix.

DATA ANALYSIS

In order to empirically test the formulated hypotheses while controlling for possible confounding variables, I rely on multivariate regression models. To shed light on the effect of interest group mobilization on parties’ policy agendas, the specific structure of the dataset has to be taken into account. The observations in my dataset are not independent as assumed by ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. On the one hand, the observations are clustered into five political parties and eleven issue areas. In order to address this problem, I estimate regression models with clustered robust standard errors that account for this twofold clustering into political parties and policy issues. On the other hand, I study party issue attention over time as parties’ policy agendas in elections from 1987 until 2009 are analysed. This timing component may result in autocorrelation in the dependent variable. In order to control for potential autocorrelation, I follow Beck and include the lagged dependent variable in the regression analyses.Footnote 68

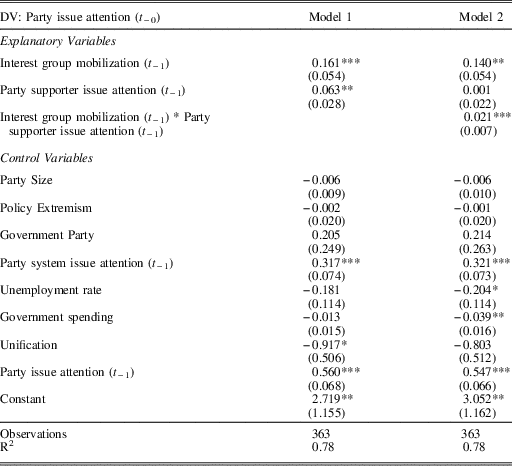

Table 1 presents the results of the time-series cross-section regression analysis. Model 1 shows that interest group mobilization has a positive and statistically significant effect on the attention that parties pay to policy issues. The higher the interest group mobilization in an issue area in the year preceding the election, the higher the emphasis that parties place on this issue area in their election manifesto. More specifically, as the relative number of interest groups lobbying in an issue area increases by one percentage point, the attention that parties devote to this issue area rises by 0.161 percentage points. Thus, the emphasis that parties place on policy issues in their election manifestos is indeed positively related to interest group mobilization. In comparison, the attention that party supporters pay to policy issues also has a statistically significant positive effect, but the magnitude of the effect is considerably smaller. An increase of party supporter issue attention (similarly measured as percentages) by one percentage point only increases parties’ issue attention by approximately 0.063 units. Accordingly, the standardized regression coefficients show that while a one standard deviation decrease in interest group mobilization would yield a 0.11 standard deviation increase in parties’ issue emphasis, a one standard deviation increase in party supporters’ issue attention only results in an increase of 0.06 standard deviations in parties’ issue salience. Hence, interest group mobilization plays a more important role for political parties than the concerns of their own voters when deciding which issues to emphasize.Footnote 69 Given that the lagged dependent variable has a considerable effect on the attention that parties pay to policy issues at t −0, it furthermore has to be noted that the effect of interest group mobilization on party issue emphasis is even stronger than the estimated instantaneous effect indicates. Since interest group mobilization at t −1 has an effect on party issue attention at t −0, interest group mobilization at t −1 will also have an effect on party issue attention at t 1 through the lagged dependent variable (and so forth).Footnote 70

Table 1 The Effect of Interest Group Mobilization on Parties’ Issue Attention

*** p≤0.01, ** p≤0.05, * p≤0.10; Clustered robust standard errors in parentheses.

In order to illustrate the estimated effect of interest group mobilization at t −1 on parties’ issue emphasis at t −0, I have simulated predicted values as suggested by King, Tomz, and Wittenberg.Footnote 71Figure 1 shows on the y-axis the predicted party issue attention at t −0 while the x-axis represents interest group mobilization at t −1. The solid line indicates the point estimates while the dashed lines illustrate the 95 per cent confidence interval. Figure 1 clearly demonstrates that the attention that political parties pay to a policy issue systematically increases with the mobilization of interest groups in that issue area. Thus, an increase in the number of interest groups that lobby in an issue area goes hand in hand with an increase in party issue emphasis. Thus, political issues that trigger interest group mobilization in the year preceding a Bundestag election receive considerably more attention by political parties in their election manifestos than policy issues that are of little concern to interest groups.

Fig. 1 Effect of interest group mobilization The figure is based on model 2.

Model 2 additionally includes an interaction effect between interest group mobilization and party supporters’ issue attention to test whether the issue priorities of party supporters condition the interest group effect. The interaction exhibits a statistically significant and positive effect as suggested by hypothesis 2. Thus, the positive effect of interest group mobilization on parties’ issue emphasis indeed increases with the salience of issues among party supporters. It is important to note that the insignificant effect of party supporter issue attention in model 2 solely indicates that the effect of party supporter issue attention does not have a statistically significant effect when interest group mobilization is 0 as one cannot interpret constituent terms as main effects in regression models.Footnote 72 To further illustrate how party responsiveness to interest groups varies with the importance of issues to party supporters, I have computed a marginal effect plot as recommended by Brambour, Clark, and Golder.Footnote 73Figure 2 demonstrates the responsiveness of political parties’ issue agendas to interest group mobilization depending on how important policy issues are to their own voters. More precisely, the figure shows the marginal effect of interest group mobilization at t −1 on party issue attention at t −0 as the salience of issues among party supporters at t −1 varies. The solid line indicates the point estimates while the dashed lines illustrate the 95 per cent confidence interval. The figure clearly demonstrates that the positive effect of interest group mobilization on parties’ issue emphasis steadily increases with the attention that party supporters devote to policy issues. Hence, interest groups find it easier to place their issues on the policy agenda of parties when their issue priorities coincide with those of their electorate.

Fig. 2 The conditioning effect of party supporters’ issue attention The figure is based on model 2.

To further illustrate the magnitude of both effects, I have estimated predicted values for different levels of interest group mobilization and party issue attention, drawing on the simulation approach by King, Tomz, and Wittenberg.Footnote 74Table 2 contains the predicted values of party issue attention at t −0 for different values of interest group mobilization at t −1 and party supporter issue attention at t −1 together with the 95 per cent confidence interval. When no interest group mobilizes on an issue, the attention that parties pay to this issue is on average 4.94 per cent when party supporter issue attention is at its mean value. If 5 per cent of all interest groups that registered at the Bundestag in a given year lobby in the same policy domain, parties devote on average 5.93 per cent to the issue in the next year when party supporter issue attention is at its mean. Similarly, if 10 per cent of all the interest groups that lobby the Bundestag are active in the same policy area, political parties on average spend 6.92 per cent of their manifestos on this issue in the next year when party supporter issue attention is at its mean value. Finally, if 15 per cent of all the interest groups that registered at the Bundestag lobby in the same policy domain, parties will on average devote 7.91 per cent of their election manifestos to this issue in the next year when party supporter issue attention is at its mean. To understand the conditioning effect of party supporter issue attention at t −1, one can furthermore compare the predicted values of party issue attention at t0 across different values of party supporter issue attention at t −1 when interest group mobilization at t −1 is constant. For instance, the predicted party issue attention when interest group mobilization is 10 per cent varies from 6.25 per cent (minimum value of party supporter issue attention), to 6.92 per cent (mean value of party supporter issue attention) and 14.79 per cent (maximum value of party supporter issue attention). Thus, interest group mobilization has a sizeable effect on party issue attention that is considerably conditioned by the emphasis that party supporters place on an issue.

Table 2 Illustration of the Effects (Predicted Values)

Only interest group mobilization and party supporter issue attention at t −1 are changed; all other variables are held constant. The predictions are based on model 2.

With regard to the control variables, only two variables have a consistent and robust effect on party issue attention. First, in line with previous research,Footnote 75 the regression analyses show that political parties adjust their issue profile to the issue agenda of their rival parties. The lagged party system issue attention has a statistically significant positive effect on a party’s issue emphasis. Thus, the higher the average salience of an issue among all parties in a party system, the more this issue is emphasized by a party. Second, the lagged dependent variable similarly exhibits a statistically significant positive effect across both model specifications. Thus, the attention that a party pays to an issue is importantly affected by a party’s previous issue agenda.

One can furthermore argue that there may be interaction effects at play in the sense that some parties respond more strongly to voters or interest groups respectively. In order to capture such effects, additional model specifications were estimated in which interaction effects for the party-specific properties party size, government status and policy extremism and (a) party supporter issue attention and (b) interest group mobilization were included. The results are reported in table A.10 and A.11 in the Appendix. None of the interaction terms exhibits a robust statistically significant effect across the model specifications while the main findings remain essentially the same.Footnote 76

CONCLUSION

Do political parties respond to interest groups? While the responsiveness of political parties to voters has received widespread attention in recent years,Footnote 77 it has been unknown so far how interest groups affect parties’ policy agendas. In order to close this important gap in the literature, this article has shed light on the relationship between parties and interest groups to understand whether parties respond to lobbyists when deciding which policy issues to emphasize. It has been argued that political parties respond to interest group mobilization as lobbyists offer valuable information, campaign contributions, electoral support and personal rewards. However, since political parties need to satisfy voter demands to secure their re-election, interest groups were expected to be particularly able to shape the policy agenda of political parties when they prioritize policy issues that are also important to voters. The theoretical expectations were tested based on a novel empirical analysis that combines an unprecedented longitudinal dataset on interest group mobilization with data on parties’ issue emphasis in election manifestos and voters’ issue priorities gathered from public opinion surveys. Based on a time-series cross-section regression analysis studying the responsiveness of five major German parties across eleven issue areas and seven elections from 1987 until 2009, it has been demonstrated that parties adjust their policy agendas in response to interest group mobilization and voter demands and that interest groups are more successful in shaping party policy when their priorities coincide with those of the electorate.

The findings have important implications for our understanding of political representation. According to our common understanding of the representative role that political parties play in Western democracies, parties should represent the interests of their voters to whom they are accountable.Footnote 78 Citizens act as principals who delegate the power to make policy decisions to political parties through elections. An important prerequisite for a functioning representative democracy is the congruence of voters’ policy priorities with the policy agendas of the parties they have voted for.Footnote 79 The findings of this study show that parties are however not only responsive to their voters, but that they also listen to interest groups when deciding which policy issues to emphasize. In fact, the voice of interest groups is much louder than the voice of ordinary citizens as parties more strongly adjust their policy agendas in response to interest group mobilization than in response to voter concerns. Even though interest groups are also important intermediary organizations that transmit societal preferences to parties,Footnote 80 party responsiveness to interest groups might result in an important bias as not all societal interests are equally able to mobilize.Footnote 81 Thus, interest group lobbying undermines the electoral connection between parties and their voters as well-organized societal interests that are represented by numerous lobby groups have a much better opportunity to be heard by political parties than ordinary citizens.

Even though this study has made a first step in shedding light on how interest groups influence party agendas, this study was limited to investigating the impact of interest group mobilization on party agendas in Germany. Despite the fact that Germany is just one case with some particular features, such as its fairly moderate party system or its strong reliance on majority coalitions, I do not expect dramatically different findings in other democratic countries as Germany also shares many similarities with other political systems. First, the German electoral system is a mixture system which combines elements of a proportional and a majoritarian electoral system. Some MPs receive their seats through a majority vote in their districts while other MPs win their seats based on the proportional list vote. Thus, Germany allows for comparisons with both proportional and majoritarian systems. Second, Germany is characterized by a multiparty system which was long composed of two catch-all parties and the smaller liberal FDP, but which witnessed the emergence of new parties over the course of the last thirty years, namely the Green party, the socialist Left party and more recently the right-populist Alternative for Germany. It therefore shares many similarities with other multiparty systems such as Austria or Sweden. Finally, the composition of the German interest group population very much resembles the interest group population in other countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Denmark and even the European Union.Footnote 82 In addition, the patterns of interest intermediation combine elements of corporatism and pluralism, thus allowing for comparisons with many other interest group systems.Footnote 83 Given the similarity of its electoral system, its multiparty system and its interest group system to many other political systems around the world, it is reasonable to expect similar findings in other democracies. However, the external validity can of course only be ensured if the effect of interest groups on parties’ issue agendas is analysed in other countries and I thus hope to stimulate further comparative research replicating the analysis in systems with differing institutional structures, party and interest group systems.

Finally, another important avenue for future research is to systematically take into account corporate lobbying by individual companies. This study has provided an important contribution by exploring the effect of lobbying by membership organizations on parties’ issue agendas, but given that the Bundestag lobbying register excludes companies, it is unclear what effect corporate lobbying has on the issue portfolio of political parties. Lobbying by individual firms is not a negligible phenomenon. Wonka et al. show that 13 per cent of all the actors that registered in the EU lobbying register are corporations.Footnote 84 Similarly, Baumgartner et al. find that 14 per cent of all advocates lobbying on the nearly 100 policy issues they studied in the US were firms.Footnote 85 To compare the Bundestag lobbying register with another data source mapping lobbyists in Germany, I have conducted an additional analysis of all the door passes that were granted by the Bundestag to external actors in 2014. This analysis showed that about 20 per cent of all the door passes were issued to companies, including think tanks and law firms who lobby on behalf of other actors. Thus, future research needs to extend the analysis presented in this by article by systematically exploring how corporate lobbying might affect the issue agenda of political parties.