Several authors have called for increasing attention to the structures, processes, and practices underpinning negotiations of gender identity and equality in organizations (Ely & Padavic, Reference Ely and Padavic2007; Grosser, Moon, & Nelson, Reference Grosser, Moon and Nelson2017; Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013). However, limited attention has been paid to the complex intersections between gender and religion in the quest to theorize gender equality in business ethics (Fotaki & Harding, Reference Fotaki and Harding2018). In a guest editorial in Business Ethics Quarterly, Grosser et al. (Reference Grosser, Moon and Nelson2017) called for a more rigorous integration of feminist theory into business ethics research. This article contributes to this endeavor by “articulating the relationships between gender equality and business ethics” (Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Moon and Nelson2017: 553) in a religious context.

By assessing the mutual dynamics of gender and religion, this article combines feminist theories of gender grounded in an Islamic feminist perspective with theories of respect. The simultaneity of gender and religion (cf. Holvino, Reference Holvino2010) captured in Islamic feminist theory is particularly relevant to understanding gender equality in the Middle East–North Africa (MENA) region and the influence thereof on development processes. Recent studies have highlighted that notions of equality cannot be understood in isolation from women’s wider status in society (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017; Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013; Koburtay, Syed, & Haloub, Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2011; Omair, Reference Omair2008; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014). Rather, a critique of these discursive formations requires a fluid public–private continuum (Badran, Reference Badran2009) to negotiate and unsettle the boundaries of gendering processes.

In line with recent calls for Islamic approaches to business ethics (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017; Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2011; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014; Tlaiss, Reference Tlaiss2015), this article contributes to advancing knowledge in two main areas. First, it introduces an Islamic feminist perspective to the study of gender at work in business ethics. In the process, it develops a novel theorization of (in)equality by integrating an Islamic feminist lens with theories of respect. This allows a capturing of how inequality is institutionalized and (re)produced across different levels through status beliefs. Second, by integrating feminist theories of “doing gender” with an Islamic feminist perspective of “doing religion,” this article challenges and further extends this theoretical conceptualization to question dominant notions of respect. In the process, it reconfigures the current debate on gender equality.

To present key, original contributions to this area of study, the article is structured as follows. First, the interrelationships between Islam, gender, and work are explored. The moral foundations that serve to legitimize gender relations and equality often draw on the proximity of religion and ethics, especially in Muslim-majority countries (MMCs) (Madigan, Reference Madigan2009; Stowasser, Reference Stowasser1994). Religion-based social norms and values are usually not captured by dominant feminist and organizational theories due to their “failure to speak to traditional Muslim culture” (González, Reference González2013: 28). By adopting an Islamic feminist perspective, this article aims to advance extant knowledge on gender equality in business ethics by studying the diverse, and often contradictory, religious discourses surrounding women’s employment.

Second, the methodology and the wider study context are presented. This research adopts an ethnographic lens to develop a socially embedded perspective of gender equality at work. This allows a capturing of the informal processes of organizing that often remain elusive in the more apparent dynamics of gender segregation in MMCs.

Third, in the discussion of findings, this article proposes a conceptualization of (in)equality as an aspect of (un)equal regard rooted in the different valuation of genders. This concept builds on the social norm of respect and the effects stemming from a differentiated sense of entitlement to respect experienced by women and men. This moves beyond a notion of material resources and power as key markers of status beliefs and instead focuses on “the effects of status—inequality based on differences in esteem and respect” (Ridgeway, Reference Ridgeway2014: 1).

Fourth, the discussion section advances a fuller comprehension of the socially situated mechanisms that (re)produce gender inequality at work, proposing potential implications for practice and future research, followed by concluding reflections.

ISLAM, EQUALITY, AND GENDER

Modernity’s confinement to the secularization thesis has contributed to the exclusion of religion from normative discussions of equality (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2016; Avishai, Reference Avishai2008). Modernization, however, has not led to the secularization of MMCs. Islam is the dominant religion in forty-nine countries, and it is the fastest-growing world religion, with more than 1.6 billion followers worldwide (De Silver & Masci, Reference De Silver and Masci2017). However, it is more than a religious tradition, reflected through its strong interweaving with the cultural formation of Islamic states, their legal systems, and notions of citizenship (Badran, Reference Badran2009; Moghadam, Reference Moghadam2002; Treacher, Reference Treacher2003). Many of the developments, including increasing urbanization and public education, have contributed to a blurring of the division between scriptural and popular Islam (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2016; Silverstein, Reference Silverstein2012). This becomes apparent in the ways in which religious interpretations have shaped “the vast range of symbolic, discursive, and institutional domains” composing “Islam as a lived experience” (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2016: 227). Irrespective of these developments, women’s participation in the labor market in MMCs, especially in the Arab-Muslim bloc, has stalled over the past three decades (Sidani, Reference Sidani2018).

Over the same period, Islamic feminism has become part of a wider transnational discourse. Equality forms a fundamental component of Islamic feminism, which is grounded in the Quran (Badran, Reference Badran2009). While recent studies have alluded to this body of knowledge (see, e.g., Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013; Koburtay et al., Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018; Syed & Ali, Reference Syed and Ali2019; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014), a thorough engagement therewith to advance conceptions of gender equality in business ethics is missing. Islamic feminists do not critique Islam per se but the human interpretation of Islamic doctrines (Badran, Reference Badran2009; Charrad, Reference Charrad2011; Mernissi, Reference Mernissi1991; Mir-Hosseini, Reference Mir-Hosseini2006; Omair, Reference Omair2008). Islamic feminists argue that the historical legacy, and the predominant male “voice” in Islamic theology, has led to gender-unequal interpretations of religious sources despite the egalitarian principles of Islam (Badran, Reference Badran2009; Mernissi, Reference Mernissi1991; Moghadam, Reference Moghadam2002). This requires an acknowledgement of the limitations and impossibility of applying the Islamic denomination in a universal sense. Rather, Islamic refers to a “community of discourse” of Islam (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2016), which plays a crucial, albeit diverse, role in the culturally embedded experiences of Islam as part of everyday life.

Studying the intersections between the discursive traditions of Islam and gender requires an understanding of the primary sources. These include the Quran, whose text is considered to be the direct revelation from Allah received by Prophet Muhammad and the hadith (prophetic traditions), that is, the collected sayings and actions of Prophet Muhammad (Wadud, Reference Wadud2006). The exegesis (tafsir) of Quranic sources in relation to the roles ascribed to men and women and the relationships between them can be seen as a form of gender analysis:

In the Quran, religiously constructed duties, responsibilities and possibilities for Muslims are often (though not always) indicated with specific reference to male or female (al-dhakar and al-untha) and man or woman (al-rajul and al-mar’a) (Badran, Reference Badran2009: 198).

The hadith “provide guidance in translating the scripture’s message into practice and serve as the highest exemplar of lived Islam” (Badran, Reference Badran2009: 245). They are regarded as the explanation of the Quran and, hence, have a strong influence on Islamic interpretations (Roald, Reference Roald, Ask and Tjomsland1998). There is no one official institution entitled with the epistemological authority to “speak truth” about Islamic interpretations (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2016). However, there exists a complex systematic approach to verifying the authenticity of hadith and their compliance with the Quranic teachings. Fatima Mernissi (Reference Mernissi1991), a Moroccan sociologist, highlights that many hadith that do not fulfill the two stipulations continue to be used within Islamic theology. She describes this as the “structural characteristic of the practice of power in Muslim societies” (9). This contributes to the widely situated, socially diffused experience of Islam and its gendered imprimatur upon everyday life.

Islamic feminists seek to advance the egalitarian principles of Islam through performing ijtihad, which is considered to be an independent interpretation of religious sources (Badran, Reference Badran2009). Ziba Mir-Hosseini (Reference Mir-Hosseini and Yamani1996), an Iranian legal scholar, is one of the first women to engage in a critical gender-sensitive reading of the Sharia. Amina Wadud (Reference Wadud2006), an American Islamic theologian, has provided a critical rereading of the Quran from a woman’s perspective. These gender-progressive readings constitute a revolutionary practice in a context where religious epistemology is considered a domain of male authority. They further provide an important foundation for the two research questions guiding this article: How do religion-based social norms and values influence the (re)production of gender inequality? What are the underpinning inequality-(re)producing mechanisms at play in these processes? These research questions carry a global relevance that extends beyond MMCs. However, their meaning becomes embodied and, arguably, most relevant in countries where patriarchal interpretations of Islam have shaped political and legislative systems.

DOING GENDER AT WORK

Women in the MENA region experience the most extensive barriers to accessing work and navigating the workforce (World Bank, 2018). Prevailing social norms are often perceived to be the key barrier to women’s employment (Elamin & Omair, Reference Elamin and Omair2010; Koburtay et al., Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018; Syed, Ali, & Hennekam, Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018). These norms are circumscribed by religious interpretations that have shaped women’s position in society and their participation in the labor market. Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) is based on the Quran and the hadith, but codification of Sharia law differs from region to region. The Sharia describes good behavior and rituals embodied in the Quran, forming the basis of Islamic ethical imperatives (Badran, Reference Badran2009). It shapes conceptions of gender equality, as women’s rights are anchored in Sharia law through the personal status code, also called family code (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi2003):

Nowhere has fiqh been more pervasively used to disrupt the Qur’anic notion of equality and gender balance than in modern shari’a-backed Muslim personal status laws or Muslim family laws enacted as state law (Badran, Reference Badran2009: 245).

Most Arab countries have not “introduced secular laws of personal status to replace the laws based on Islam” (Omair, Reference Omair2008: 117). For example, in Tunisia, codification favored women’s rights after French colonial rule ended, while this was not the case in Morocco or Algeria (Charrad, Reference Charrad2011). Some countries, especially in the Middle East, base their employment laws on the Sharia (Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2011; Roald, Reference Roald, Ask and Tjomsland1998). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), for example, has a historically low female labor force participation rate, having been around 18 percent in 2017 (Bursztyn, González, & Yanagizawa-Drott, Reference Bursztyn, González and Yanagizawa-Drott2018). The application of employment law is guided by individual judges’ interpretations of the Sharia. A recent report by the World Bank (2018) identified twenty-eight legal gender differences. These are applied and interpreted differently in local customs and management practices, elucidating how legal aspects become interwoven with ethical conduct. The notion of male guardianship, in particular, often functions as a restraint for women’s labor force participation and continues to play an important role in women’s employment decisions (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018; World Bank, 2018).

It is difficult to advance women’s rights and gender equality without undergoing equal shifts in social attitudes and norms (Sidani, Reference Sidani2005). In the quest for emic approaches to understanding equality and gender, Syed and Özbilgin (Reference Syed and Özbilgin2009) developed a relational, multilevel framework, which has been adopted in different contexts, including in Pakistan, Turkey, and KSA (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017; Özbilgin, Syed, Ali, & Torunoglu, Reference Özbilgin, Syed, Ali and Torunoglu2012; Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018). The framework categorizes female modesty and gender segregation as macro-level barriers to women’s employment. Gender segregation across space functions as a key marker of status hierarchies in organizations (Wasserman & Frenkel, Reference Wasserman and Frenkel2015). Many organizational reforms appear inherently gender-neutral. However, these reforms “often entail a redefinition of the gendered divisions of labour and assumptions about women’s and men’s work roles in the organizations” (Tienari, Quack, & Theobald, Reference Tienari, Quack and Theobald2002: 250).

The strong prevalence of religion-based social norms functions both as a silencing mechanism, by making it difficult to thematize the issues women face in their working lives (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017), and as a form of narrated ethics. Informal discourses in organizations often serve to enforce social norms (Waddington, Reference Waddington2012). Gossip, for example, represents a wider “discursive practice—often strongly ritualized—through which social values are communicated to, and reproduced by, the members of that culture” (van Iterson, Waddington, & Michelson, Reference van Iterson, Waddington, Michelson, Ashkanasy, Wilderom and Peterson2011: 375). Different studies have alluded to gossip as a barrier to women’s employment and participation in society more widely across the MMCs (González, Reference González2013; Khan, Munir, & Willmott, Reference Khan2007; Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018; Syed, Ali, & Winstanley, Reference Syed, Ali and Winstanley2005). Gossip can function as a segregator by differentiating between who is considered an “insider” or an “outsider” and by shaping who is perceived to be “better qualified” or “established” in social as well as work situations (van Iterson et al., Reference van Iterson, Waddington, Michelson, Ashkanasy, Wilderom and Peterson2011).

The underlying dynamics sustaining inequality regimes are driven by normalized perceptions of women’s and men’s status or “place” in society (Koburtay et al., Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018; Tienari et al., Reference Tienari, Quack and Theobald2002). Women’s modesty reflects an important Islamic virtue (Mahmood, Reference Mahmood2011; Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Winstanley2005), which is intended to safeguard family honor (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018). While modesty is expected of both men and women in the Quran (Sidani, Reference Sidani2018), interpretations thereof are often used to exclude women from the labor force and public life more widely (Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014). Norm conformity therefore rests strongly on women’s behavior, and the possibility of norm transgression has important implications for how we understand norm compliance or deviance (Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen, & Smith-Crowe, Reference Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen and Smith-Crowe2014).

INEQUALITY-(RE)PRODUCING MECHANISMS

When analyzing inequality, Acker (Reference Acker2006: 455), Ridgeway (Reference Ridgeway2014), and Fenstermaker, West, and Zimmerman (Reference Fenstermaker, West, Zimmerman, Fenstermaker and West2002) have emphasized the need for a strategic focus on specific “inequality-producing mechanisms.” These mechanisms cannot be predetermined. Instead, they require a critical engagement with different forms of organizing to explore the relational interdependence between social conceptions of status value and individual agency at work. The notion of the abstract/gender-neutral worker (Acker, Reference Acker1990: 149) remains relevant in this context. “It reveals unique stability in the connection between women’s personal experience as wives and mothers and women’s social status as workers” (Fenstermaker et al., Reference Fenstermaker, West, Zimmerman, Fenstermaker and West2002: 25). Organizations as gendered processes rely on different interlocking practices, processes, and symbolic expressions of gendering (Acker, Reference Acker1990). Acker (Reference Acker2006, Reference Acker2012) uses an intersectional approach to study the underlying inequality-producing mechanisms that drive the “unequal symbolic allocation of recognition, power and status between men and women” (Healy et al., Reference Healy, Tatli, Ipek, Özturk, Seierstad and Wright2019: 1751).

Women continue to hold “highly variable degrees of social and employment status” (Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013: 350; Koburtay et al., Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018), which emphasizes the difficulty of capturing and addressing inequality regimes in MMCs. Özbilgin et al. (Reference Özbilgin, Syed, Ali and Torunoglu2012) explore the feasibility and challenges associated with transferring gender equality policies and practices in employment from a Western to a MMC context. They emphasize the importance of context over essence in adapting principles and practices. This also requires a consideration of ongoing debates on (tribal) culture, to capture multiple confluences of oppression (Koburtay et al., Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018; Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018; Tlaiss, Reference Tlaiss2015). Karam and Jamali (Reference Karam and Jamali2013) suggest a range of initiatives that organizations can adopt to promote women’s participation in the workforce in MMCs. These represent important advances toward identifying culturally sensitive management practices and policies. Syed and Van Buren (Reference Syed and Van Buren2014: 271) further highlight the importance of these being “consistent with the economic capabilities of women.” These studies concur that workable approaches to gender equality need to take religious requirements into consideration (Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013; Özbilgin et al., Reference Özbilgin, Syed, Ali and Torunoglu2012; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014).

Syed (Reference Syed2008: 148; see also Syed & Ali, Reference Syed and Ali2019) proposes a gradual transition toward a “modern but customized Islamic model of equal opportunity.” Syed and Özbilgin’s (Reference Syed and Özbilgin2009) relational framework reflects an important step in this direction, as it provides a multilevel perspective on the various factors that shape women’s access to employment. Capturing the dynamic interdependency between these levels is key to grasping the complex interaction between structure and agency in gendering processes. However, the underlying inequality-(re)producing mechanisms remain vague and ambiguous. This article identifies respect and shame as critical mechanisms in these processes. It focuses on respect, as designated by an epistemic-like authority encapsulated in religious interpretations and norm perceptions that shape the prevailing understanding of status at the societal level.

Respect is theorized based on Darwall’s (Reference Darwall2006) concept of honor respect. Honor respect is a form of recognition respect, which concerns how our relations to each other “are to be regulated or governed” (Darwall, Reference Darwall2006: 123). Darwall (Reference Darwall2013) posits that honor respect differs from mutual (recognition) respect, as it emphasizes differences in status and is conferred on individuals by society. This aligns with Islamic feminist perspectives elevating the role of honor and morality in circumscribing gender relations (Badran, Reference Badran2009; Stowasser, Reference Stowasser1994; Treacher, Reference Treacher2003; Wadud, Reference Wadud1999, Reference Wadud2006). Islamic feminists highlight that a woman’s respect in Islamic communities serves to verify the collective dignity of her family (Stowasser, Reference Stowasser1994). Honor respect in Islamic societies hence rests on the behavior of women. The need to maintain family honor has been identified as having a key influence on women’s employment decisions (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018). However, conceptions of honor respect based on religious norms are not static. Rather, they are discursively enacted, symbolized, and sustained through doing gender. Hence, respect becomes relationally constituted through the ways in which (personal) status beliefs circumscribe individuals’ agency.

Conceptions of gender equality in Islam are rooted in an “equal but different” philosophy (Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2007). Patriarchal interpretations thereof serve to (re)produce a wider discourse that emphasizes the need to create moral work environments to protect women (Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2011). The complex ramifications of religion-based social norms and values across the societal, relational, and individual levels contribute to the normalization and (re)production of the differential valence of genders rooted in respect. A more careful attention to these interlocking processes could provide meaningful insights into the underlying inequality-(re)producing mechanisms.

METHODOLOGY

This problem-driven research (Reinecke, Arnold, & Palazzo, Reference Reinecke, Arnold and Palazzo2016) is guided by the question of how religion-based social norms and values influence the (re)production of gender equality at work. In the Global Gender Gap Report, Morocco is ranked 141st out of 149 countries in economic participation and opportunity for women (World Economic Forum, 2018). Women’s labor force participation remains at a rate of 25 percent, with the male labor force participation rate being 74.1 percent, a distribution similar to what is found in Tunisia and Egypt (United Nations Development Programme, 2018). This research aims to elucidate the underpinning inequality-(re)producing mechanisms at play in these processes by exploring women’s access to employment in the rural parts of the Marrakech-Safi region.

The Berber-Muslim communities of the High Atlas Mountains have experienced dramatic developments in infrastructure (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman, Hoffman and Miller2010) and tourism over the last two decades (Eger, Scarles, & Miller, Reference Eger, Miller and Scarles2019). However, these developments have not equally contributed to increasing employment levels among women. The primary allegiance to the household and idealization of women as symbols of purity draw wider parallels to understanding gender in Islam (Mernissi, Reference Mernissi1991), while being unique in their intersection with Berber culture (Becker, Reference Becker, Hoffman and Miller2010). Hence, it is important to highlight the specificity of the context, which is presented in the next section.

Study Context: The Berber Population of the High Atlas Mountains

The Berbers are an ethnic group native to North Africa. Berber is a primarily oral language with the tribal organization often following the division of dialects. There is a fluidity between Berber culture and different forms and practices of Islam (Silverstein, Reference Silverstein2012). The type of Islam that was historically promulgated in North Africa was legal Islam based on the Maliki school of jurisprudence (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi2014). The rural Berber population of the High Atlas Mountains adopted Islam as an “indivisible and non-negotiable aspect of their personal and social identity” (Silverstein, Reference Silverstein2012: 349–50). The Berber women’s transformation of dress illustrates this dynamic relationship, with the veil being “Berberized” by local women by adding colorful embroidery (Becker, Reference Becker, Hoffman and Miller2010). Through these Islamic influences, clothing acquired a religious conservative valence that is still evident in the Berber villages visited during the fieldwork for this study.

The Berber groups’ religious practices were less scripturally based, though, partly due to the Berber people not being well versed in Arabic and to prevalent illiteracy in general. The Berber integrated “popular Islam” as part of their customs and beliefs (Silverstein, Reference Silverstein2012), including traditions of music, dance, and oral poetry (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi2003). Islam-as-practice plays an important role in structuring daily life and as part of rituals and ceremonies. Marriage celebrations illustrate the complex combination of Berber customs, such as the use of fertility symbols, and Islamic traditions, including polygamy. Polygamy is practiced across the villages, especially in Aremd, where community members were considered to be more affluent.

There were no restrictions on marrying men from other areas, with a young Berber woman arguing, “Allah decides. It is not in your hands” (Int54-F).Footnote 1 The rights and responsibilities of husband and wife are recorded in the Islamic marriage contract. Mir-Hosseini (Reference Mir-Hosseini2003: 12) argues that “the reason why ‘women’s status’ and gender relations became fixed matters in fiqh is rooted in the tension between the dictates of wahy [voice of revelation] and those of social order.” The marriage contract reflects this tension, as the social order usually prevails over the voice of revelation (Mir-Hosseini, Reference Mir-Hosseini2003). This is reflected in the quote of a young Berber woman engaged to be married after Ramadan, who argued that her right to work was determined by her marriage agreement:

Her [future] husband cannot let her go to work. She can tell him that she wants to work, but he cannot accept, because they talked before. She should stay at home and he can work (Int54-F).

It remains difficult to evaluate the adoption of Islamic cultural practices, as these have become engrained in the local way of life. Respondents were often unable to differentiate between Berber and Islamic traditions. Hoffman (Reference Hoffman, Hoffman and Miller2010) notes that there was generally a shift away from customary law toward an increasing adoption of the Sharia, signifying increasing familiarity with Islamic principles. This becomes apparent in the personal status code being one of the first laws passed after the French colonial rule ended. It emphasized women’s domesticity, restricted their overall rights, and institutionalized polygamy (Mernissi, Reference Mernissi1991). Perceptions about women’s domesticity were anchored in cultural interpretation of Islam, as reflected in the quote from Int58-F, a Berber woman/housewife:

The religion says that the woman has two movements; she will go from the family home to the husband home and from the husband home to dying.

The family code is the only area in Moroccan law that is regulated by the Sharia (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi2003). Wide-ranging changes were made to the family law in 2004 (Salime, Reference Salime2012), which included the right to self-guardianship, and made the wife and husband equal heads of the family (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi, Kelly and Breslin2010). However, the realization of these changes often hinges on their practical implementation, especially when laws are perceived as contrary to social norms (Koburtay et al., Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018).

Women are perceived as holders of purity and tradition (Becker, Reference Becker, Hoffman and Miller2010), symbolizing tribal notions of (male) honor. Koburtay et al. (Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018) mention similar causes of gender inequality among Bedouin tribes that intersect with Islamic interpretations of (male) honor. The Islamic precept that women should not associate with non-mahram (unrelated) men serves to reinforce notions of gender segregation across different spheres (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi2014). “We hear almost nothing about women, children, or non-saintly men” (Crawford, Reference Crawford, Hoffman and Miller2010: 129). The relegation of Berber language and culture to the private sphere further contributed to these processes (Hoffman & Miller, Reference Hoffman, Miller, Hoffman and Miller2010).

When talking about the ways in which gender is portrayed in their communities, respondents often referred to Islamic teachings. For example, the Berber woman/housewife who commented that “women only have two movements in life” argued that she learned this from the Imam in the mosque, as illustrated in the following quotation:

Everyone says that Islam says that. I can’t read, but the Imam who prays with the people in the mosque says that. The Imam, every time I listen to him, he talks about the woman, every time (Int58-F).

These teachings influence religion-based social norms and values. Widespread illiteracy and the persistent gender gap in education (Eger, Miller, & Scarles, Reference Eger, Miller and Scarles2018) further limit women’s ability to question dominant religious interpretations. The social organization of gender in the villages depends largely on the institution of the family, which represents a set of values that goes beyond “the Western notion of a ‘nuclear family’” (Crawford, Reference Crawford, Hoffman and Miller2010: 130). This applies to MMCs more widely, where the family “permeates society upward and outward, personalizing societal institutions in a way not found in the west” (Omair, Reference Omair2008: 117). Especially in rural areas, the local way of life of the Berbers continues to be tightly interwoven with agriculture and animal husbandry, with the family representing an economic unit. Women tend to be responsible for social reproduction work and (unpaid) farmwork, illustrating the gender division of labor, which continues to adhere to strict social norms. This is illustrated in the quote from Int27-F, a Berber woman/housewife who works on her family farm:

A woman can work on her farm, but she cannot work with others for paying her because the people will talk about the woman who works with other people on their farms.

Women carry a large share of the unpaid work underpinning subsistence farming. A common picture in the local villages is of women carrying large loads of grass to feed their animals. Economic development has been mounting over the last two decades, with many, predominantly male, community members finding work in tourism. However, these developments have not equally benefited women’s access to paid employment, as aforementioned. Affording increasing spaces for women’s economic participation combines in complicated ways with Berber culture and Islamic conceptions of honor, which is explored in more detail in the analysis of findings.

Methods

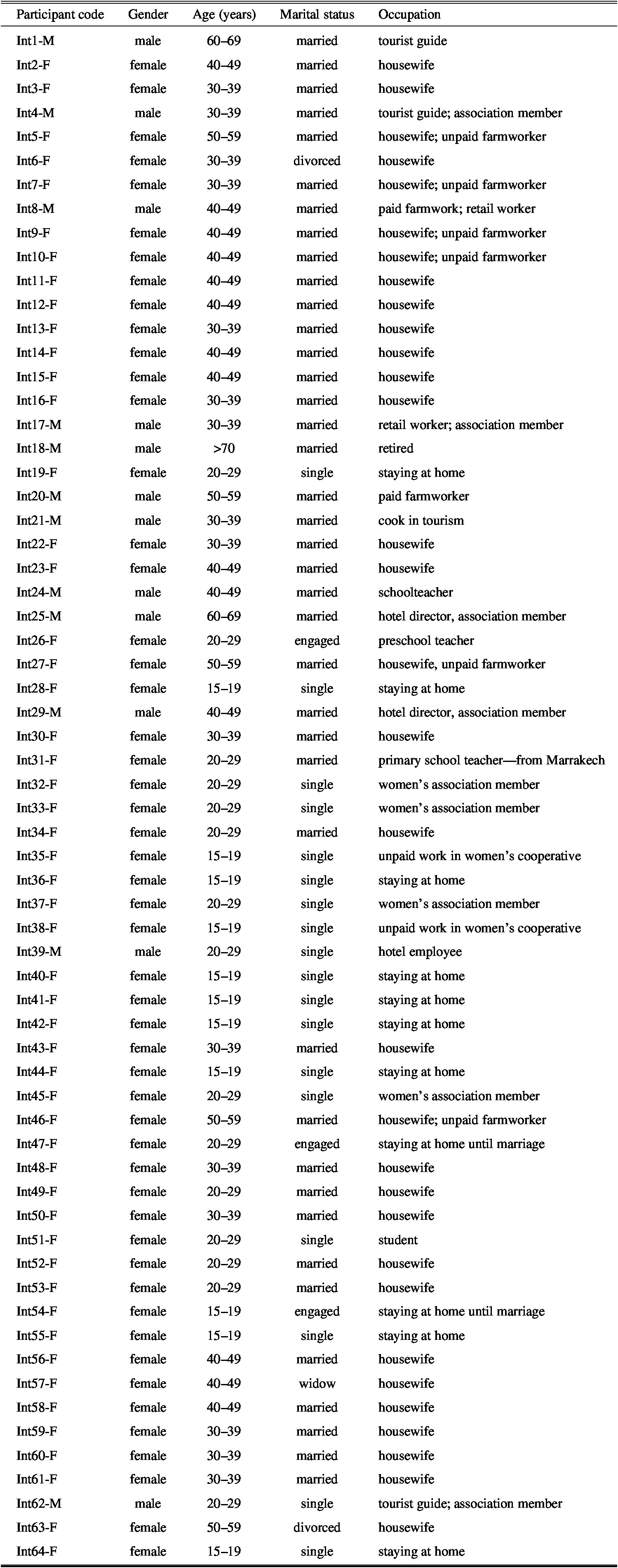

The research is based on six months of ethnographic fieldwork that combined qualitative interviews and participant observation. The author conducted sixty-four in-depth interviews with Berber women and men, becoming a participant-as-observer while living in the local villages (Behar, Reference Behar1996). The identification of community members was based on purposive sampling combined with a snowballing technique (King & Horrocks, Reference King and Horrocks2010). The latter supported the purposive sampling approach, as the researcher was able to identify relevant participants through previous respondents and other community members. The researcher selected participants from a range of villages to gain a deeper understanding of the phenomena being studied. The women were usually approached in their homes, while working in the fields, or in local women’s cooperatives/associations, whereas the men were primarily approached in local stores and association buildings. Conducting the interviews in a variety of settings allowed the researcher to observe and experience the dynamics underpinning the local gender regime.

The researcher conducted observations while visiting and living in local households, attending literacy classes, joining community members in association meetings, and during visits to local women’s cooperatives. Over time, the relationships established with community members led to a forming of trust as well as invitations to social events like marriage celebrations. This enabled an embodied understanding of space to evolve through shared emotions and experiences, but also through the negotiation of space set within the community frameworks. The mediation of local hierarchies and power through space provided an alternative insight into how people “do” gender and religion and how gender intersects with other aspects, such as age and ethnicity. The interview situation described in the following field diary entry exemplifies this:

When Fatima [anonymized] arrived, she invited us to the house, and we sat down in the salon. It was a tense atmosphere. Fatima … explained that her grandfather and grandmother were at the house and that they would think bad things if she did the interview with us. I asked her whether we could do an interview with her brother… . Doing the interview with her brother seemed to be a green light to also do an interview with her… . The whole interview with Fatima took place in a slightly oppressive environment, with her brother eavesdropping from time to time, her family passing by the door constantly, and her grandmother standing in the door checking on us and what we were talking about (field diary extract, May 30, 2014).

Situated knowledges are co-constructed by the researcher and participants’ subjectivities and identities (Haraway, Reference Haraway1988). The role of axiology plays an important role in this process, emphasizing not only the moral responsibilities that the researcher carries but also the potential influences that her values can have on the knowledge production process (Guba & Lincoln, Reference Guba, Lincoln, Denzin and Lincoln2008). As such, it is important for the reader to understand the positionality of the researcher, who comes from an international background, having lived in countries including Germany, Burkina Faso, Peru, and Colombia and having worked across geographical regions including Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Tanzania. The experience gained from working with different cultures across the world evokes a sensitivity to cultural difference. This, combined with having the identity of a white, highly educated, middle-class, and nonreligious individual, contrasts with the research setting in which most individuals are Berber, practicing Muslims, and working class and have no or a relatively low level of education. The author shares the experience of Manning (Reference Manning2018), who describes herself as the “Other” in her research with indigenous Maya women. This conscious experience of the self is tied to different forms of understanding and the negotiation thereof in the dialogical encounters with the lifeworld of the research participants.

Gaining insight into situated knowledges is premised upon an increasing sensitivity toward local norms, beliefs, and values, while experiencing gender relations in situ. Recognizing the limitations of her own positionality as non-Muslim, the author adopted an Islamic feminist lens to gain a more situated and contextualized understanding of equality and gender but refrained from quoting religious texts as a sign of respect. The embodied experience of fieldwork also encompassed an examination and redirection of the self. This can be exemplified through the researcher’s changing experience of space. At the beginning of the research, the author was unaware of the marketplace (souk) being primarily a male space and conducted an interview with a local shop owner in the midst of the souk. Her personal feelings of shame over conducting interviews in the souk grew over time, indicating how the local politics of gender had become part of her own embodied understanding of space.

This observation correlates with the notions of body learning and body sense described in Mahmood’s (Reference Mahmood2011) analysis of ethical formation. A researcher’s “moral commitment constitutes the self-in-relation” (Christians, Reference Christians, Denzin and Lincoln2008: 205), which can also represent a challenge as the researcher is engaging in “the same moral space” (206). This can lead to one experiencing difficulties in interview situations, for example, when respondents express views with which the researcher disagrees, such as “no women should work” or “women cannot learn like men.” This requires a respect for difference to be able to understand difference. Keeping a field diary helped to reflect on those experiences, which in turn evoked a critical self-awareness (Coffey, Reference Coffey1999).

A collaboration with two female Berber translators played a crucial role in establishing proximity with the research participants. The translators shared a similar cultural background and experience with the respondents, which helped develop a sense of trust and rapport. For example, a woman told the translator that men were taking advantage of women’s illiteracy by letting them sign contracts where they agreed that the husband could have another wife without them being aware of this. The women felt embarrassed to tell this to the author but trusted the translator with these stories. Working together with translators enabled meaning-based interpretations (Esposito, Reference Esposito2001) but added to the complexity of multiple subjectivities encompassing this process. While disputes over meaning and discourses are central to gaining a situated understanding of equality, the ethical framing of work practices from an outsider’s perspective can have serious social consequences if it does not capture all relevant dimensions (Khan, Reference Khan2007; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Munir and Willmott2007).

The researcher’s prolonged engagement in fieldwork and the use of triangulation enabled an immersion into the new social and cultural context (Denzin & Lincoln, Reference Denzin, Lincoln, Denzin and Lincoln2008). However, language barriers complicated the intersubjectivity of interpretation (cf. Schwandt, Lincoln, & Guba, Reference Schwandt, Lincoln and Guba2007). The translation of interviews required increased sensitivity toward the interview process and knowledge transfer (Berman & Tyyskä, Reference Berman and Tyyskä2011). The engagement in persistent observation allowed for the collection of thick descriptive data, with the triangulation of data supporting the exploration of emerging claims from different perspectives. These processes supported both the credibility and the transferability of the findings (Schwandt et al., Reference Schwandt, Lincoln and Guba2007), strengthening the development of the conceptual case (Guba & Lincoln, Reference Guba, Lincoln, Denzin and Lincoln2008).

Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed by the author after the fieldwork ended, representing a vital phase in the initial process of analysis. The average length of interviews was one hour. The data were analyzed using thematic analysis, which is a useful approach to investigating a group’s understanding and conception of the studied phenomena (Joffe, Reference Joffe, Harper and Thompson2012). This is consonant with the ontological and epistemological underpinning of this research, which favors an emic approach to knowledge production. Thematic analysis is concerned with “identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006: 79).

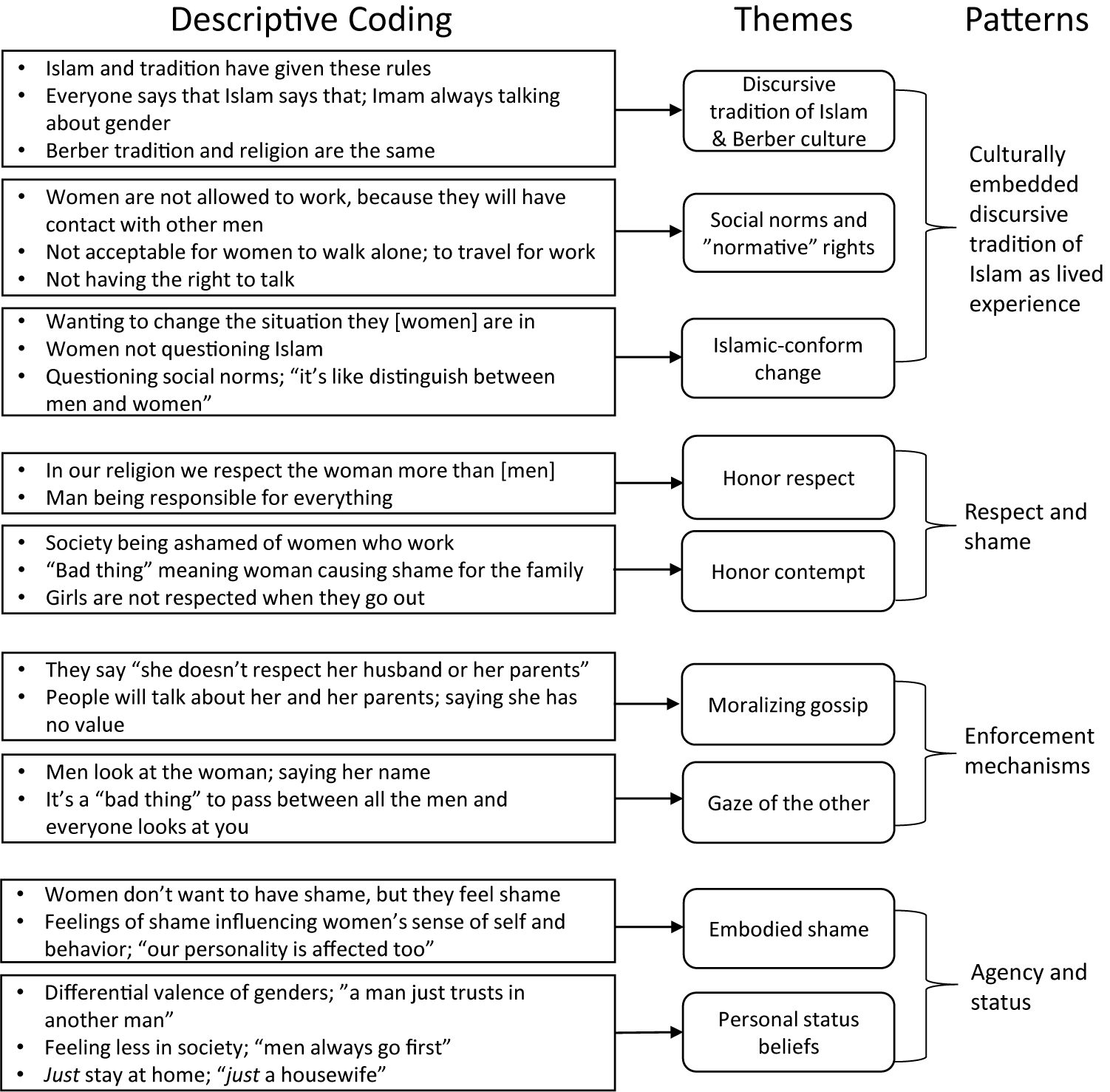

A three-staged thematic analysis approach was employed based on descriptive coding, thematic coding, and a third stage of coding in which the principal patterns were identified (King & Horrocks, Reference King and Horrocks2010). The emerging coding structure is depicted in Figure 1. Using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo 10 helped organize the data and the iterative coding processes. To ensure the anonymity of the research participants, data are anonymized with numbered interviews, and the gender of respondents is indicated with the letter F or M (e.g., Int1-M, Int2-F). These codes are used as identifiers in quotations from interviews reported herein. The appendix presents the participants’ demographic information.

Figure 1: Thematic Coding Structure

GENDER (IN)EQUALITY: RESPECT AND SHAME

The Quranic idea of equality is based on gender differentiation and is commonly depicted as women being equal to men, but also different (Madigan, Reference Madigan2009; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2007; Syed & Ali, Reference Syed and Ali2019; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014). While men and women are described as “equal in their humanity and their dignity” (Syed, Reference Syed, Özbilgin and Syed2010: 213), they are assigned similar but different rights in Islam. Syed (Reference Syed, Özbilgin and Syed2010) describes this as a form of qualitative rather than quantitative equality, which diverges from an equal employment opportunity discourse. Several authors have emphasized the importance of introducing Islamic-conform equality policies to support the gradual transformation of local gender regimes (Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013; Özbilgin et al., Reference Özbilgin, Syed, Ali and Torunoglu2012; Syed & Ali, Reference Syed and Ali2019; Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018; Syed & Özbilgin, Reference Syed and Özbilgin2009; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014). However, this raises questions about the ways in which equality is understood in a MMC context.

Equality is constructed as a rationality for gendering processes (Benschop & Doorewaard, Reference Benschop and Doorewaard1998), with religion-based social norms and values upholding the notion of the complementarity of gender roles (Badran, Reference Badran2009). The complementarity argument often serves to legitimize status hierarchies. Qualitative equality (cf. Syed, Reference Syed, Özbilgin and Syed2010) based on an “equal but different” ethos requires accounting for (un)equal constructions of worth and for who is making those definitions of value. Islamic feminists advance a critical interpretation of religious sources inclusive of women’s experiences, which is key to moving toward greater gender justice and equality in Islamic thought and practice (Wadud, Reference Wadud1999). This study proposes that gender-differentiated notions of respect serve to (re)produce inequality. Sensitive to the gendered experiences of both culture and religion, this research extends current knowledge on the specific mechanisms through which inequality is (re)produced.

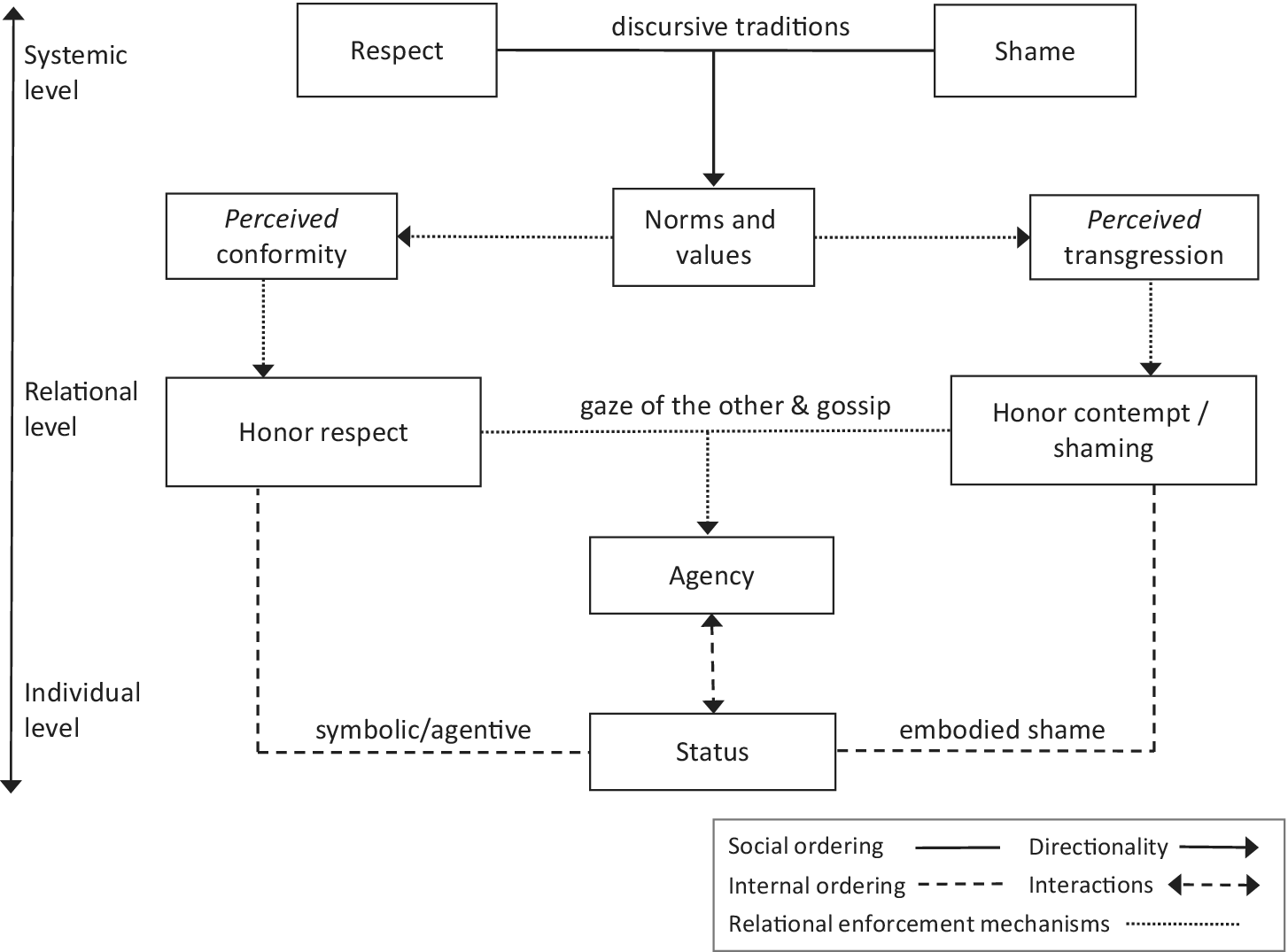

The discussion of findings is supported by a conceptual summary diagram (see Figure 2), which illustrates how inequality is institutionalized and (re)produced across different levels. The systemic level captures the social ordering of gender based on notions of respect and shame. The culturally embedded discursive traditions of Islam become institutionalized through religion-based social norms and values. The adherence to these norms is relationally negotiated through conceptions of honor respect and honor contempt, with the latter being underpinned by processes of shaming. Perceived conformity or transgression is judged through moralizing gossip and the gaze of the other, which constitute relational enforcement mechanisms. The mere possibility of transgression alludes to the ubiquitous continuum between honor respect and honor contempt, which is underpinned by embodied forms of shame and agentive versus symbolic forms of honor respect. These contribute to the internal ordering of status and circumscribe individuals’ sense of agency.

Figure 2: Conceptual Summary Diagram

The subsequent analysis sheds light on the complex ways in which the identified inequality-(re)producing mechanisms of respect and shame have profoundly shaped the gender division of labor in the High Atlas Mountains’ Berber communities. First, the ways in which status value and agency are circumscribed through gendered conceptions of respect are analyzed. Second, the interconnection between respect and shame is explored by alluding to its nexus across different levels. Third, the relevance of the relational enforcement of norms across these levels is highlighted through an exploration of the practice of gossip and the gaze of the other.

Status Value and Agency at Work

The findings of this study indicate that the strong correlation between masculinity and women’s honor represents a legitimizing basis on which the different valuation of men and women is translated into societal inequality. Women’s honor symbolizes men’s dignity (Stowasser, Reference Stowasser1994). “This treatment of women as symbols or objects instead of independent participants in the society has resulted in strong stereotypes faced by women” (Syed, Reference Syed2008: 144). A Berber woman/housewife comments, “Boys make a family in the future, and they must have good work for the families, but girls will just be a housewife in the future” (Int16-F). Both masculinities and femininities are being constructed through these discursive practices, but the former are given a more agentive role, while the latter have a rather symbolic meaning ascribed.

A young man, working as a tourist guide and a local association member, highlights the protective role that Islam grants women: “We find in the religion that the one who must pay for everything is the man. The reason? It’s always to protect the women” (Int62-M). It is the man’s religious responsibility to care financially for the family (Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014) and to protect women’s honor, which is the practice of qiwama (protection) (Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2011). This role is reflected through the institutionalization of male leadership of the household, as illustrated in the quote from Int12-F, a Berber woman/housewife:

The man takes care of everything. He is the one who is responsible for everything, who provides everything the house needs. He pays for the water, the electricity, everything. The man is the one who does it.

The quote supports the views of a young Berber man expressed in Int62-M, who argues that men are perceived as strong, competent, and in a position to assume responsibility: “The man, he can support himself” (Int62-M). Dominant perceptions of masculinity are performed by earning a living and are connected to competence and status (cf. Acker, Reference Acker1990, Reference Acker2012). This encapsulates the vision of men as providers for the family, which results in greater competence and worth being attributed to a man compared to a woman. “Competence expectations become the basis of deference … confer[ring] situational worthiness,” being a “highly implicit version of the more general cultural beliefs that give a characteristic status value” (Ridgeway, Reference Ridgeway1991: 374).

Men’s status as breadwinners, and to a certain extent also as guardians, entitles them to exert control over women’s choices, functioning as a key restraint to a woman’s agency. Badran (Reference Badran2011: 78) argues that gender inequality within the family, “sustained by fiqh-backed, state-enacted laws,” remains one of the most pressing feminist challenges in MMCs. A young Berber woman argues, “The religion says that the men will control everything in their family and in their house” (Int33-F). This places men’s duty to care for the family over women’s rights—from a normative standpoint—to access work and education, illustrating how status differences are materialized through different forms of entitlement.

These processes and status hierarchies tacitly inform the valuation and construction of choice, influencing a woman’s perceived (in)ability to act (Eger et al., Reference Eger, Miller and Scarles2018), as illustrated by a Berber woman in the following quote: “The husbands say: ‘We have a home. I have money. Why go to work?’ They don’t accept” (Int32-F). This, in turn, has an effect on resource distribution, which is disproportionally in favor of men (Ridgeway, Reference Ridgeway1991) and strengthens the differential valence of genders. A Berber woman/housewife emphasizes that men are always given preference in society in the subsequent quote:

It is better for men to be educated than women. Men always go first. So, if he is educated, he will provide everything for his wife, and if they [the wives] need something, they [the wives] will ask the husband (Int57-F).

Women are assigned a “special care” status, meaning the expectation of a certain (protective) treatment that proliferates from the home into the workplace (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017). The “special care” status becomes apparent in the ways in which Berber women and men portray the gender division of labor, using the conception of respect to justify that division—(re)producing inequality:

In our religion we respect the woman more than [men], because the woman can’t support herself… . That is why they should just do the work here at the home (Int62-M).

The complementarity argument is implicit in the gender discourses, “placing” women within society by emphasizing the gendered spatial division of labor. “The religion gives a lot of rules. Women should just stay at home and pray, not going outside, just stay at home” (Int12-F). This, in turn, serves to limit women’s access to paid employment, as illustrated by a Berber man in the following quote:

Firstly, in the religion the best job for the women or for the girls is to look after the children. So, the things that she can do just at home. The other work is hard work. Working on the land, for example, it’s hard work and the women can’t do it. For that reason, I think the women and girls they are just doing the work here at the house (Int62-M).

The complex intersection between sexuality, gender roles, and religious identity captures how exclusion persists and serves to complicate work relationships (Acker, Reference Acker2012). While motherhood and child-rearing are described as an elevation of women’s status (Becker, Reference Becker, Hoffman and Miller2010), these are both roles derived from women’s sexuality, which remains an area of controversy in Islam (Madigan, Reference Madigan2009). Islamic feminists have critiqued the social construction of sexuality (Mernissi, Reference Mernissi1996), with a woman’s sexuality often being portrayed as a distraction to the male mind (Mernissi, Reference Mernissi1985). Mernissi (Reference Mernissi1991) and Treacher (Reference Treacher2003) argue that the complementarity of genders rests on an understanding of gender relations naturalized through sex and institutionalized through men.

While a multiplicity of meanings underpin the performances of religious identity (Wadud, Reference Wadud2006), the intersection of sexuality and gender has played an important role in influencing the wider societal imagination of women at work. Supposed psychological and embodied differences between genders are often cited as grounds for exclusion or restrictions on women’s access to employment (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Winstanley2005). This is exemplified through the description of women in the local villages as weak, sensitive, and fainthearted. “The woman is a sensitive person and she has no power” (Int4-M), a Berber man comments. A paid farmworker justifies women’s limited mobility based on these perceived differences:

Everyone says the woman is a weak person. She has a weak personality and can’t go in this way [to commute] every day and come back (Int20-M).

Perceived differences in bodies also translate into perceived differences of capability. These beliefs are reproduced in the labor market, for example, through the perception of women’s mythic emotionality (Acker, Reference Acker1990). A Berber man working in retail comments,

There are men in the association [at work] and they are using the women just for other goals. They are using them because, emotionally, the woman is very weak (Int17-M).

In the context of this study, conforming to women’s economic capabilities (cf. Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014) would imply an accommodation to prevailing gender stereotypes. The underlying norms draw on gendered conceptions of respect, in which women’s agency becomes circumscribed by an honor–shame discourse (re)producing inequality. While adherence to norms leads to honor respect, agentive forms of honor are primarily attributed to men “who build a family.” Status beliefs hold that men are more competent and esteemed. Women’s “care status,” on the other hand, has a symbolic value ascribed that results in a woman’s sense of entitlement to respect being continuously (re-)negotiated, making it contingent upon norm-conform behavior:

A Berber woman/housewife said, … if the people think the woman did something wrong, she will lose the religion and she will lose the value between people in the community and make the family also lose the value. All of them, the religion and the Berber culture, they are the same thing; they are taking care of the woman (Int23-F).

Perception plays an important role in these processes, as it is the gaze of the other that serves to determine perceived norm transgression or conformity. This implies that honor respect is not merely bestowed upon individuals by society but also actively negotiated in everyday life. This contributes to processes of gendering in which the possibility of norm conformity versus transgression alludes to a gendered continuum of honor respect and shame, as illustrated in Figure 2.

The Moral Relevance of Shame

To question the systemic relevance of respect requires an engagement with shame. The differential valence of genders rests on a societal understanding of respect and shame. Symbolic honor is incurred through women’s adherence to religion-based social norms, while honor contempt remains present, prescribing the possibility of norm transgression resulting in shaming (see Figure 2). This alludes to the moral relevance of shame in shaping individuals’ status value. A woman’s modesty and propriety are a symbolic reflection of a man’s respect in society (Mernissi, Reference Mernissi1996). A woman’s behavior is judged through norm prescriptions, and she could lose “her” (family) honor if she were perceived as shameful, as illustrated in this quote from a Berber woman/housewife:

Whenever a woman goes to work, people in the village talk badly about her, and they say that she has no value, and that she has no one to control her. It’s the same reason that makes the girls stop education that makes the women stay at home [rather than] work (Int61-F).

This article proposes that the mutual interdependence of honor respect and honor contempt circumscribe an inequality-(re)producing mechanism rooted in the shame nexus (cf. Creed et al., Reference Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen and Smith-Crowe2014). The complex functioning of shame as an underlying mechanism delimits what and who is to be respected, and in which ways. Shame “imposes physical and psychological boundaries on Muslim working women” (Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Winstanley2005: 154). Normative conformity is achieved through intersubjective forms of power (Creed et al., Reference Creed, Hudson, Okhuysen and Smith-Crowe2014), hence the importance of accounting for the relational enforcement mechanisms of social norms in Figure 2, which is contrary to a conception of honor respect as being primarily bestowed upon individuals by society (cf. Darwall, Reference Darwall2006, Reference Darwall2013).

This research finds that the shame nexus can limit what a woman aspires to become and do, as illustrated in the quote from a young Berber woman: “Women don’t want to have shame for themselves, but they feel shame. The woman feels it in her inside. Women feel that they cannot do anything without asking” (Int51-F). Mahmood (Reference Mahmood2011: 15) argues that “agentival capacity is entailed not only in those acts that resist norms but also in the multiple ways in which one inhabits norms.” The shame nexus alludes to the risk of gender assessment and religious assessment (cf. Avishai, Reference Avishai2008; West & Zimmerman, Reference West and Zimmerman1987), and the interplay thereof can result in the feeling of not being recognized as equal in society. Embodied shame hence is key to moral consciousness, reflecting how an individual can inhabit norms.

In the local belief system, a woman who engages in paid employment outside of her home or pursues her education in another village is perceived as losing her value in society, which in turn diminishes the honor of her family. There were some exceptions to the perceived shame associated with women’s employment if a woman was divorced, widowed, or not yet married. Understanding the relationality of honor respect and honor contempt hence requires a deeper engagement with the epistemic-like authority that constitutes the wider discursive tradition of (in)equality in Islam. So, too, does the relational enactment thereof, through which status value becomes recognized and (re)produced:

I want[ed] men to respect the women … to be respectful, friendly and to not talk badly about the women (Int16-F).

In the foregoing quote, a young Berber woman/housewife emphasizes the need for more respect from men. This contradicts the aforementioned respect ensued through women’s “care status.” Rather, most Berber women identify themselves as “just” housewives, or say they “just” stay at home. A young Berber woman working as preschool teacher said, “The women who just stay at home and do housework like cooking and these things, their personality is affected too—they feel that they are less in the society” (Int26-F). These processes reproduce the gendered conception of status, attributing a symbolic care status to women. This, in turn, circumscribes their agency and sense of status. These gender discourses are relationally enforced through informal practices, including gossip and the gaze of the other.

Relational Enforcement Mechanisms

The mutual negotiation and enforcement of religion-based social norms and values play a distinct role in the formation and maintenance of group norms and power structures as well as changes thereof. The use of gossip in relation to gender performances is intended to preserve social order in the Berber villages. A woman’s virtuous behavior and (in)visibility constitute the reversed gaze of shame, which is relationally enforced through gossip (see Figure 2). This serves to (re)produce dominant conceptions of gender-appropriate behavior and “punishes” deviance thereof. Hence, it is consequential “who gossips to whom about what, and about how and where gossip happens” (Waddington, Reference Waddington2012: 1). Waddington highlights the visual (embodied) dimension of gossip through which shaming can be exercised through nonverbal and material practices. When a young Berber woman currently staying at home was asked why she stopped working in the local women’s association, she answered,

The problem is that the association is in Imlil. They must always walk through the souk and the men and the boys look at you. Then they come back to Mazik and talk to the parents, “your daughter always takes the way of souk and the boys and the men see them.” … The women don’t want to pass in front of the men. The women are shy … , but the men just look at her and say her name. The other people think that they have a relationship, just because he knows her name (Int28-F).

The breaking of spatial distance through the gaze of the other (in this case, the woman being looked at and her name being mentioned by a man) is described as proof of intimacy. It is taken as proof that modesty has been broken, hence resulting in honor contempt through shaming. When asked what she thinks would change if more women were to go out and work, she replied,

It’s not dependent on the woman, because if other people tell her husband that his woman did something bad, he can trust the [other] people; he cannot trust the woman. It’s not dependent in your personality; it’s dependent on your family or on your husband (Int28-F).

Gossip represents a constant threat to a woman’s status, as his word will be believed over hers, symbolizing the differential valence of genders. This also affects women’s underlying sense of self, as illustrated by a young Berber woman:

People say bad things about women, and the women cannot defend themselves. She didn’t do these things. That is why it destroys her (Int37-F).

Women’s social identity is mediated by this form of hegemonic gossip. Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Munir and Willmott2007) report similar issues in their study of the soccer ball industry in Pakistan, where women preferred to work from home rather than engaging in factory work to avoid being shamed. “Respect is important for women, and the visible daily commute to centers exposes their self-respect to scathing verbal assault by villagers, particularly men” (Khan et al., Reference Khan, Munir and Willmott2007: 1068). This elucidates how status beliefs are relationally (re)produced and gossip as well as the gaze of the other are the practices by which values are upheld and policed.

The risk of losing the security of marriage without any empowering alternative, such as work, implies that women are often left in silence. A male farmworker highlighted, “If she has worked, she will never marry in the village … because they are hearing bad things about her, and he is seeing her everyday with other people” (Int20-M). This silence has deep-seated emotional and psychological effects on women, while being profoundly interwoven within the societal and familial structures that tolerate it. In the following quote from Int15-F, a Berber woman/housewife articulates her embodied experience of silence:

They cannot challenge their husbands. If they challenge the husband, maybe women get divorced, and then no one can help them, because they don’t have work. … That is why they don’t have the right to talk.

This links back with bargaining theories where patriarchal risk is perceived to decrease women’s sense of entitlement, influencing the power structures within the household (Sen, Reference Sen1985, Reference Sen1999).

Madigan (Reference Madigan2009) illustrates how inheritance laws serve to mathematically decrease a woman’s position in society. In Morocco, these laws are enshrined in the family code, with men inheriting twice as much as women, which institutionalizes patriarchy (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi2014). In rural areas, women often receive nothing, in return for family protection. The “central role of patrilineal affiliation in inheritance laws entail the legal dependence of wives and children on their closest male relatives” (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi2014: 100). The man has ownership over the familial property, while the woman has access to property mainly through the man. Women are positioned in relationships of dependence, which has further repercussions on individual agency. These forms of status are reflected in daily interactions, where a man’s competence and position in communication are perceived to be superior to a woman’s position. This functions to uphold dominant conceptions of respect, as illustrated in the subsequent quotes from two Berber women emphasizing that a man’s word is valued more than a woman’s word:

If someone comes and tells him that his daughter did something, he will believe that man rather than his daughter. They [men] don’t trust them [women], or the family, or their daughter. A man just trusts in another man (Int56-F).

When women go to the souk [market] in Imlil the other people talk bad about them. A woman is afraid about the family reputation. If a man talks bad about her, others will believe the man, not her (Int64-F).

This skewed conception of respect discourages women from opposing men’s demands. More specifically, it forfeits a woman’s access to recourse, making her dependent on a man’s word. Norm conformity and transgression, hence, become dependent on the word and gaze of the other. While some community members do not agree with the social norms, they are hesitant to transgress these, for example, by deviating from traditional gender divisions of labor for fear of social sanctions:

They still think that women’s work is a bad thing and shameful, because even if someone wanted to give permission to his wife to work, the others would be telling him, “Do you not control your wife? Why is she going to work? Do you need something?” (Int22-F).

In the foregoing quote, a Berber woman/housewife emphasizes that the perceived norm transgression would question the agentive honor respect of men. The question “Do you not control your wife?” illustrates how the relational negotiation of social norms serves to circumscribe individual agency. While this includes a man’s agency to transgress norms, it has a much more constraining effect on women, whose symbolic status position needs to be continually upheld (cf. Stowasser, Reference Stowasser1994). Religion-based social norms hold that a woman has to work in spaces segregated from men, which translates into unequal access to job opportunities. This is illustrated in the quote from Int4-M, a Berber man working as a tourist guide:

No one lets his wife work, because the wives will come into contact with other men. So, if there is a project just for women, and women are the only members of the association, it’s okay. But if there is a man, no.

Gender segregation can be related to “the law of ‘hudud’ (frontiers supposedly separating the male and female spaces)” (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi2014: 89). A woman incurs shame for herself and her family if she is perceived to transgress these frontiers. While the preference for gender-segregated workspaces is prevalent across different MMCs (González, Reference González2013), the focus on Berber women’s lived experiences of Islam and access to employment brings to light the underpinning ambivalence and often conflicting interpretations of women’s status. Women “bear the weight of patriarchal honor” (Badran, Reference Badran2009: 171), with a man’s honor depending on a woman’s perceived conformity to religion-based social norms and values. A man is entitled with the normative right to work based on an agentive status value, as “he makes a family.” A woman’s normative right to work rests on her upholding of morality (and tradition), that is, a symbolic “care status.” Overcoming these gender-unequal status beliefs requires a wider systemic change in the dominant conceptions of respect and shame to amplify a woman’s perceived and embodied freedoms.

DISCUSSION

Gender is often described as standing at the center of the contradictions of modernity in Islam (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed2016; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan and Abu-Lughod1998). These contradictions become particularly pronounced when discussing women’s access to paid employment. This provided the impetus for studying two interconnected research questions: How do religion-based social norms and values influence the (re)production of gender inequality? What are the underpinning inequality-(re)producing mechanisms at play in these processes? This article finds that the strong correlation between masculinity and a woman’s honor represents the legitimizing basis on which gender-differentiated notions of respect are translated into societal inequality. Prevalent norms are strongly focused on women’s behavior, and ethical values are constituted according to these norms. This is similar to findings by Mahmood (Reference Mahmood2011), who argues that norms are not only imposed but also lived and inhabited, which makes the meaning of agency emergent.

This research finds that individuals’ adherence to religion-based social norms is relationally negotiated through conceptions of honor respect and honor contempt. Perceived norm-conform behavior leads to honor respect, while honor contempt is incurred through a perceived norm transgression leading to shaming. At the individual level, the reversed gaze of shame becomes part of a self-addressed demand to perform gender according to religion-based social norms. This forms a self-regulating process, emphasizing the interconnection between the sociality of shame and embodied shame.

Both Islamic and Berber traditions elevate the importance of (male) honor, with women’s honor being a symbolic reflection of men’s dignity, as emphasized by Mernissi (Reference Mernissi1996) and Stowasser (Reference Stowasser1994). The findings of this study further develop the meaning this carries for gender (in)equality. While adherence to norms leads to honor respect, agentive forms of honor are primarily attributed to men, whereas women’s “care status” has a rather symbolic value ascribed. The mere possibility of norm transgression serves to reaffirm a woman’s status or “place” in society, as it encapsulates the supposed need for protection to safeguard family honor. This leads to a constant (re)negotiation of a woman’s symbolic honor respect, making it contingent upon norm-conform behavior.

This article identifies respect and shame as key inequality-(re)producing mechanisms contributing to unequal constructions of status value. Their interdependency forms the moral boundaries that connect cultural constructions of honor respect with embodied feelings of shame, having a profound influence on gender divisions of labor. Relational enforcement mechanisms function both as silencing mechanisms and as forms of narrated ethics in these processes, alluding to the fluidity and interdependence between value claims and norm perceptions.

Other studies have emphasized the interplay between progressive and traditional forces in querying women’s official status in employment in MMCs (Mir-Hosseini, Reference Mir-Hosseini2003; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014; Syed, Reference Syed, Özbilgin and Syed2010). This article provides a culturally embedded perspective thereon, with the findings of this study highlighting the difficulty of disrupting the “doing” of gender and religion. Transformations in the realm of gender require equal shifts in religion-based social norms and attitudes delimiting who is to be respected and in which ways. Through these processes, status beliefs based on gender-differentiated notions of respect acquire a profound resonance with individuals’ normative right to work, shaping the basis on which women can enter the workforce.

Gender Equality and Business Ethics in a Religious Context

Gender equality and respect for religion represent central concerns for advancing business ethics in a MMC context. This requires developing religion-conform ways of operating (Ali & Syed, Reference Ali and Syed2017; Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013; Metcalfe, Reference Metcalfe2011; Syed & Van Buren, Reference Syed and Van Buren2014; Tlaiss, Reference Tlaiss2015) that recognize and acknowledge the strong moral dimension of organizational values based on respect for religion (Scott, Reference Scott2002). In MMCs, articulations of norm-conform behavior are circumscribed by religious moral pronouncements that complicate our understanding of gender equality in business ethics. This demands a thorough engagement with the simultaneity of gender and religion, to advance equality policies that support the gradual transformation of local gender regimes.

A focus on gender difference as opposed to sameness has been discussed as key to an Islamic understanding of equality, though there is scarce literature on how this understanding shapes equal opportunity in MMCs (Syed & Ali, Reference Syed and Ali2019). In focusing on the dynamic interplay between agency and structure, this article proposes respect as an original lens to study the intricate connection between systemic relationships of respect and individuals’ agency. In line with Pfeifer (Reference Pfeifer2015), the findings of this study challenge the tacit precept that religion, and, more importantly, cultural interpretations thereof, evokes a more ethical business practice. Rather, gender stratification anchored in religion-based social norms and values extends from the familial and societal realm to the organization. Badran (Reference Badran2011) highlights that gender inequality within the family remains one of the most pressing feminist challenges in MMCs.

A definition of agency in individualistic terms, independent of social norms and relations, hence remains insufficient to understand the full scope of women’s social and employment status. Instead, this article proposes that the relationship between gender (in)equality and business ethics becomes articulated through culturally embedded notions of respect, which shape individuals’ normative right to work and considerations of moral values in organizations. While business concepts are often closely intertwined with ethical concepts (Eger, Miller, & Scarles, Reference Eger, Scarles and Miller2019), moral principles rooted in religion might evade a pragmatic business sense. Pfeifer (Reference Pfeifer2015) refers to these inconsistencies and contradictions as the competing institutional logics between religion and business, which come to the fore when discussing gender equality in MMCs (see Karam & Jamali, Reference Karam and Jamali2013).

The heterogeneous discursive traditions of Islam make universal directives for business ethics practically ineffective. Rather, Wicks (Reference Wicks1996: 529) argues that “we ought to focus on how it is we ought to live, to the basic practices and activities which make for an excellent, virtuous, or caring community.” Islamic feminists have embarked on this exploration, providing unique insights into the study of gender equality in Islam. In reflecting on the relevance of Islamic feminist thought, this article advances the understanding of the intricate relationships between religion and gender in shaping inequality regimes in MMCs.

Future Directions

Future work could build on this article’s conceptualization of inequality-(re)producing mechanisms by exploring the intersections between gender and other forms of identification. Previous research has identified the roles of social class, ethnicity, and the rural–urban divide in shaping women’s access to employment (Crawford, Reference Crawford, Hoffman and Miller2010; Koburtay et al., Reference Koburtay, Syed and Haloub2018; Syed, Reference Syed, Özbilgin and Syed2010; Syed et al., Reference Syed, Ali and Hennekam2018). This indicates that conceptions of respect and shame are articulated differently depending on intersectional sensibilities and contextual realities. The focus of this study on the intersection between rural households and the wage labor sector influences the dynamics that the inequality-(re)producing mechanisms hold. Intersubjective forms of power and the structure of rural households might differ from urban household economies or from communities experiencing ethnic or religious divides. Sharpening the lens on different categories of inequality could provide valuable insights into relationships of respect, especially if combined with a multilevel methodological framework such as that developed by Winker and Degele (Reference Winker and Degele2011).

Future studies could further expand on the performativity of respect, to study its “process of iterability, [as] a regularized and constrained repetition of norms” (Butler, Reference Butler1993: 95). While individual regard is central to ethics (Darwall, Reference Darwall2013), it is circumscribed by the limits of prevailing norms and status beliefs. An individual’s “reason to value,” hence, is not merely individual but also relationally (Eger et al., Reference Eger, Miller and Scarles2018) and societally constituted (Mahmood, Reference Mahmood2011). A better understanding of the ethical formation of the self in this process would provide valuable insights into the complex interconnections between the discursive traditions of Islam, the repetition of norms, and their diverse valorization as part of everyday life. This article finds that norms are reiterated through different enforcement mechanisms, including informal discourses like gossip. Future research could investigate the ways in which gossip, as a social and cultural habit (González, Reference González2013), serves to form and reformulate prevalent conceptions of status value.