Introduction

In the early modern Iberian world, enslavement was a process that began for enslaved people in many different ways, but did not end with the legal condition of slavery. As with other categories of colonial labour (Silliman Reference Silliman2001), enslaved subjectivities were continually produced through both top-down and bottom-up forces (Stahl Reference Stahl and Cameron2008a). Advancements in archaeological theory and practice have created new possibilities for reading cultural communication and the production of enslaved subjectivities—especially in the near-totalizing institutions of agro-industrial slavery (e.g. Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2017; Bates et al. Reference Bates, Chenoweth and Delle2016; Croucher Reference Croucher, Voss and Casella2012; Hauser Reference Hauser2017; Marshal Reference Marshal2015; Ogundiran Reference Ogundiran2002). This article makes a case for the utility of an aesthetic approach to the archaeological record, drawing on philosopher Jacques Rancière's theoretical frame for thinking through aesthetics and politics. While Rancièrean aesthetic theory requires some manipulation for its archaeological application, his approach, which considers human engagement with materiality as inherently political, has the potential to offer insight into the discursive qualities of the materialized, yet near-invisible, everyday actions by subjects at the margins of past regimes.

Of particular importance to the archaeology of colonialism and slavery is the potential to shift focus beyond hybrid productions and creolizations (Silliman Reference Silliman2017) to consider the tensions and contradictions manifest in aesthetic experience. I offer an archaeological case study for such a theoretical frame through a consideration of my research on daily life among enslaved African-descended communities at two vineyards belonging to the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in viceregal Peru from 1619 to 1767. My exploration of the varied types of bodily encounters with the material world and the struggle adequately to address the political valence of such culturally specific engagements, including self-emancipatory acts of ambivalence, has led me to consider hacienda aesthetics as means to explore power and subjectivity at these estates. Although Rancière's work considers aesthetic production and politics post-Enlightenment and has not explicitly treated the issue of early modern slavery or colonialism, an aesthetic theory of cultural communication and power provides new insight into the quotidian subjectivities of the enslaved and the material worlds produced through coercive colonial labour regimes.

A focus on aesthetic fields yields new possibilities for understanding enslaved subjectivities as process and considering the dialectics of power in early modern agroindustrialism. In this approach, the ‘aesthetic’ refers to an assemblage of materialized practices, culturally bounded and experienced through the senses. These in turn generate and call upon various polyvalent signs (see Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2018), especially in a multi-ethnic population such as the Jesuit haciendas of Nasca, Peru. Rancièrean approaches to power and the social forces that regulate and produce sensory experience are revelatory for the archaeological analysis of how people engage and experience the material of our shared world through their senses—what Rancière calls the aesthetic experience. This experience is described as inherently political, divided and distributed through a socially contested system that ultimately defines how human senses operate in the world—what, for example, can or cannot be said or heard, and what can or cannot be visualized or seen (Rancière Reference Rancière and Rockhill2004, 7).

This study views the archaeology of enslavement through an aesthetico-political lens, exploring what shape Rancière's provocative suggestions could take in archaeological practice. The haciendas San Joseph de la Nasca and San Francisco Xavier de la Nasca, respectively owned by the Jesuit schools in Cuzco and Lima, represented important sources of income for their principal urban educational institutions in the viceroyalty. From their acquisition in 1619 to their expropriation by the Crown during the expulsion of the Society of Jesus from the Spanish Empire in 1767, these agribusinesses grew into the two largest and most profitable vineyards in Peru (Macera Reference Macera1966, 8–9). At the expulsion, the two wine- and brandy-producing estates held an enslaved population of 584 individuals of diverse sub-Saharan origins, which gave rise to a large African-descended community on Peru's hyper-arid south coast. Here I consider three domains of the aesthetic experience at these estates: hacienda landscape and architecture, public religious art and slave-made ceramics. After outlining the archaeological application of Rancièrean concepts for an exploration of aesthetic experience, I turn to the aesthetics of the Jesuit administration of the Nasca haciendas in space and the built environment. Then, using Rancière's speculative methodology, I discuss the potential for spectator disagreement of public religious art at the hacienda chapels via the introduction of Atlantic-African religious sign systems into the hacienda aesthetic. Lastly, I consider enslaved labour and slave-made goods, such as wine jars (botijas) and setters, as potential disruptions to early modern Western aesthetics of production.

Aesthetics, politics and the archaeological

Archaeologists have taken varying approaches to the production and place of the aesthetic and artistic expression in past societies, but most limit aesthetic experience to artistic production (see Jones & Cochrane Reference Jones and Cochrane2018). Rancière, however, suggests that the aesthetic domain should be conceived of much more broadly. Rather than the philosophy of art or a theory of its appreciation, Rancièrean aesthetics is concerned with the totality of the sensible experience. Aesthetics thus describes something about praxis materialized: the experience of the human body in contact with the material world, a shared and common world that all people inhabit. In effect, the approach picks up Yannis Hamilakis’ (Reference Hamilakis2013) charge for a ‘sensorial’ archaeology, which contends that the experience of the senses is indeed material, bounded and defined by social memory, cultural attributes and, ultimately, power. Rancière, however, is not only concerned with the materiality of the senses, but relational and hierarchical aspects of the aesthetic experience. Among the few archaeologists to recognize Rancière's utility, Adam Smith has commented that what makes his approach particularly appealing for archaeology is its ability to describe such relationships and material subjectivities (Smith Reference Smith2015a, 57). Placing materials (and people) within the aesthetic field draws out their inherent political import in subject making and processes of subjectification (Smith Reference Smith2015b). To illustrate and formalize this insight, I briefly define three Rancièrean concepts—distribution of the sensible, police and disagreement—and explain their utility for the archaeological exploration of politics and aesthetics.

Distribution of the sensible

The central concept for Rancière's approach to politics and the aesthetic is the distribution of the sensible. This is a system that defines the experience of the senses, and Rancière places this experience as central to the political. For Rancière, the very object of power is to define what is sensible, as in, among other things, what can be heard or seen. As a system, the distribution of the sensible describes evidence perceived through the senses, made apparent through cultural norms, that simultaneously identifies individual aspects of the aesthetic experience as unique, while relating it to a world common to all people (Rancière Reference Rancière and Rockhill2004, 7). The relationship between the part and the whole in the aesthetic experience is indeed a political relationship. Thus, the concept is useful for the archaeologist in thinking through relationships of scale and hierarchy, precisely describing how an aspect of the aesthetic experience relates to a regime's totality and how an individual relates to society (Smith Reference Smith2015a, 58). For example, how did everyday materials index, through the aesthetic experience, the relationship of the enslaved to histories and subjectivities of enslavement?

The police and subjectivity

The rigidity of the dominant distribution of the sensible that enforces the boundaries dividing up the way the sensible can be experienced is represented by what Rancière (Reference Rancière and Corcoran2010, 36–7) calls the police. The concept is not dissimilar to Michel Foucault's use of the term (e.g. Reference Foucault1980). For Rancière, the police is a naturalizing force, working to preserve the habitual nature of dominant aesthetic discourse, and maintains divisions between specific signs and individual subjectivities. Rancière's use of the concept is helpful as it provides language for navigating how power becomes concentrated, expressed and distributed in the material—not simply through habit, but through active policing of subjectivities experienced aesthetically through the encounter of the body with the material world.

Transformation and disruption of a police order is possible, specifically through an actor's subjectivity (Rancière Reference Rancière and Rockhill2004, 7–14). The process of subjectification, the recognition of an individual or group as members of a particular subject class or grouping, forces a reconfiguration of the distribution of the sensible. As new subjectivities are produced within a police order, they are identified relationally against each other (Rancière Reference Rancière and Rajchman1995, 66). The subjectivity of an enslaved craftsman, such as a master ceramicist, was naturalized in relation to the enslaved overseer or an enslaved fieldworker, and to the material conditions each status embodied at Spanish colonial estates. In society, individuals move in and out of subject statuses frequently, continually transforming the aesthetico-political regime in the process and altering not just expectations, but the dominant distribution of the sensible. Archaeologists of complex society, or more specifically colonialism, will find this a provocative suggestion; becoming a colonial subject—or more specifically an enslaved negro of the racio-caste designation lucumí, for example—is central to one's ability materially to disrupt or transform said subjectivity.

Politics and disagreement

For Rancière, politics is a struggle for equality, rather than the exercise of power (Reference Rancière and Corcoran2010, 27). While the police represent the rigidity of the dominant distribution of the sensible, politics is the configuration of spaces involving not the opposition between subjects with different interests, but between logics that divided up the aesthetic experience and ‘count the parties and parts of the community in different ways’ (Rancière Reference Rancière and Corcoran2010, 35). Disagreement (or dissensus) is that political process at the interface between the dominant and alternative ways of distributing the sensible and counting signs and subjectivities in relation to the whole (Rancière Reference Rancière and Corcoran2010, 37).

Herein is theoretical scaffolding for navigating the cultural transformations and continuities, and tensions and contradictions seemingly inherent in colonial experience. Whereas other archaeologists have employed terms like hybridity, creolization, bricolage and mestizaje to describe such processes (see Silliman Reference Silliman2017), the aesthetic approach compels archaeologists to consider the encounters and experiences that give rise to such tensions and contradictions. For the archaeologist of colonialism, the goal of an aesthetic approach is not to reveal the meaning(s), or intended meanings(s), of particular signs as suggested in the material record; rather, it is to speculate on the probability for disagreement—how the same signs in an aesthetic experience point to different referents for different actors.

Ambivalence as politics

Archaeologies of colonialism and slavery have struggled, and in some cases succeeded (e.g. Liebmann & Murphy Reference Liebmann and Murphy2010), in moving beyond the poles of resistance and domination in the consideration of subjectivities. An archaeology of the aesthetic opens possibilities for considering material culture as a locus of politics, especially one where contested signification and meaning is as important as active structural resistance, where ambivalence is an option with political valence. Paradoxically, the aesthetic experience both establishes hierarchies and can render subjects equals. Rancière's exploration of nineteenth-century French workers considers the actions of individuals that produced disruptions to the proper time and place for labour, for example spontaneously casting a ‘disinterested look’ while taking a moment to view the broader landscape during the flooring of a home (Rancière Reference Rancière, Rancière, Honneth, Genel and Deranty2016, 142). Similarly, ‘a disjunction between the activity of the hands and the activity of the eyes’ transgressed the way the working body was to make contact with the material world, resulting in small redistributions of the sensible (Rancière Reference Rancière, Rancière, Honneth, Genel and Deranty2016, 142). These amount to a form of ambivalence to power in which the worker produced a small rupture in the dominant distribution of the sensible and created a momentary space for self-emancipation. The archaeological case study offered below considers emancipatory aesthetics in the context of early modern colonialism and slavery. Thinking through the potential for polyvalence in public religious art, or embellishment of tools by enslaved subjects, offers ground for parsing out the tensions and contradictions of aesthetic experience, including possibilities for exploring self-emancipatory acts of ambivalence.

Jesuit administration and the aesthetics of space at the haciendas of Nasca

Space and the conditions of everyday life and labour materialized political discourse and disagreement at the Jesuit haciendas of Nasca. The processes and conditions arising in the inequalities between enslaved and enslaver and difference among individual enslaved persons are evident in routinized movements across the landscape, arrangement of the built environment and experience of productive time. Many of these configurations were deliberate administrative features of the hacienda's aesthetico-political regime, constituting a specific police regime of the distribution of the sensible. Between 1619, when the Jesuits first acquired properties in Nasca's Ingenio Valley, and 1767, when the Crown appropriated their properties during the Jesuit expulsion from the Spanish Empire, there was a concerted administrative effort to exert spatial control at the Nasca haciendas. This manifested in two ways: 1) spatial control was exerted over the estates’ domestic and agroindustrial cores, a strategy focused on the control of labour; and 2) valley-wide and regional spatial hegemony was produced through the acquisition of annexe properties to ensure the economic success of the hacienda system. The latter had the effect of projecting discipline beyond the nucleus and also routinizing and controlling movement and aesthetic experience across the landscape.

Haciendas were agribusinesses, not missions. The controlled economic growth of San Joseph and San Xavier, the principal Jesuit vineyards of the viceroyalty, was crucial for the viability of their two flagship schools in Lima and Cuzco that educated the sons of the colonial elite. Non-contiguous annexes contributed important resources, such as water rights, livestock grazing land, and waystations for transporting produce to Puerto Caballa, the (now defunct) seaport for the Grande de Nasca and Ingenio Valleys. By the mid eighteenth century, both haciendas had annexes throughout the Río Grande de Nasca drainage—San Xavier with four, and San Joseph nine (Fig. 1). Because the Ingenio Valley lacked a permanent indigenous population by the turn of the seventeenth century, hacienda growth depended on a steady increase in African-descended enslaved labour. This heavy reliance on slavery to support their operations made the Jesuits the largest slaveholder in the Americas (Alden Reference Alden1996, 542). When San Joseph was acquired by the Cuzco Jesuits in 1619, the property included only six enslaved men (AGN 1620: f. 228r). Documentation regarding early acquisitions of enslaved workers is rare, but based on patterns at other coastal Jesuit estates as well as sporadic financial data from the Nasca properties (Weaver Reference Weaver2015, 69, fig. 4.1), the population probably grew quickly. By 1767, Crown inventories list 278 enslaved people at San Joseph and 306 at San Xavier (ANC 1767a,b).

Figure 1. The Jesuit haciendas of San Joseph de la Nasca (owned by Colegio Grande de la Transfiguración of Cuzco) and San Francisco Xavier de la Nasca (owned by Colegio Máximo de San Pablo of Lima) and their annex properties.

As a particular affect of the police order for the aesthetico-political regime on Jesuit haciendas (and missions), Christian discipline was reinforced through strategies of asymmetric reciprocity, engineered social hierarchy and order, and spatial organization (Cushner Reference Cushner1980, 79–80; see also Rovira Reference Rovira1989). Early modern Jesuit attitudes toward slavery largely reflected dominant secular and Roman Catholic theological views. Racial slavery in the Portuguese and Spanish empires was shaped by the Church's approach to universalism, and as an institution theoretically protected certain civil liberties of the enslaved, including access to the Crown's courts and to the sacraments of the Church. However, in contrast to secular estates, enslaved labour as a form of Christian discipline was central to the Jesuit administrative strategy. Evangelization of the hacienda workforce was understood as both an obligation and an opportunity to expand the body of Christ and fulfilment of ‘God's Plan’ (de Borja Medina Reference de Borja Medina, Negro and Marzal2005, 93). Spiritual ‘benevolence’ was also a tool for proper exploitation of the enslaved subject's work potential (Sweet Reference Sweet1978, 128–32), and the spiritual and labour discipline of the enslaved was meant to mirror the obedience and hierarchy of the Society of Jesus’ own membership.

Administrative strategies directed a habitual and internalizing spatial control radiating from the hacienda cores to the most distant annexes, permeating the hacienda aesthetic. Walk-over survey of the eleven annexes in the Grande de Nasca Drainage reveals that investment in built infrastructure was heaviest in the sites closest to the cores of the principal estates (Weaver Reference Weaver2015, 253–303). This trend is particularly visible at San Joseph's annexe of La Ventilla and San Xavier's annexe of San Pablo, located in the middle valley of the Ingenio River. These were the only annexes to feature extensive agro-industrial complexes with wine presses, bodegas (storage and fermentation structures) and distillery apparati. Such heavy investment fortified Jesuit hegemony in the area and dwarfed the small secular farms—most of which were also focused on viticulture. With the exception of two elder residents at La Ventilla (ANC 1767a, f. 279v), the enslaved population resided at the main estates, walking daily to the fields or production sites at nearby annexes (ANC 1767a, f. 273v; 1767b, ff. 240v–241r).

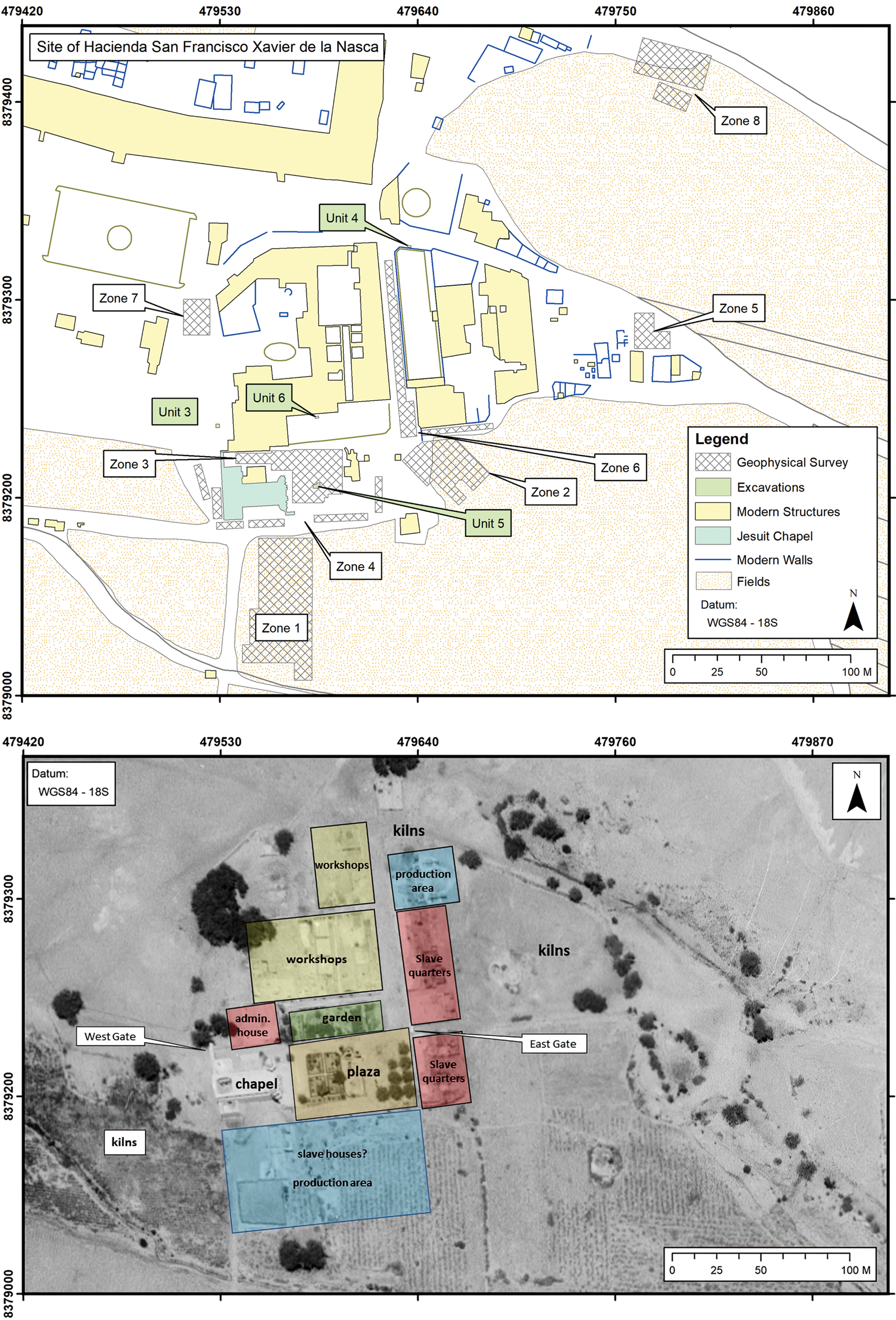

It is evident that the dominant distribution of the sensible manifested an aesthetic experience of social difference, inequality and routinized Christian deference within the hacienda space. Because the haciendas are modern towns and have undergone dramatic spatial reorganization since the Jesuit period, it has been necessary to use a broad methodology to reconstruct the earlier environments. Surface prospection, geophysical survey (electromagnetic conductivity, magnetic susceptibility and magnetometry) and excavations were combined with analysis of eighteenth-century estate inventories (ANC 1767a,b) and historical aerial photography the better to understand the evolution of the haciendas. During the eighteenth century, the built environments for both San Joseph and San Xavier were centred on open rectangular plazas (Fig. 2). This open public space was flanked by a monumental late baroque chapel, offices and residence of the Jesuit administrator, as well as workshops, storehouses, infirmaries, kitchens, a dining hall and barracks for the adolescent and unmarried enslaved, segregated by gender. The aesthetics of inequality, rank, privilege and social difference were policed in the sensory experience and key to the enslaved communities’ demography. Unlike most secular estates in Peru, the Jesuit haciendas intended to model ideal Christian society, carefully balancing male and female enslaved residents in an effort to produce familial units (see Weaver Reference Weaver2015, 115). The married and high-ranking enslaved resided in rudimentary independent housing. Enslaved master craftsmen and skilled specialists also had more choice housing, and the caporal (head slave) and his family lived in more formal quarters, featuring a window and wooden door with lock (ANC 1767a, f. 273r).

Figure 2 (opposite). (Above) Archaeological interventions in the town of San Javier; (below) Historical aerial imagery from the Servicio Aerofotográfico Nacional (1944) of the hacienda San Xavier with schema of possible eighteenth-century site layout.

Ingress and egress to the hacienda core was restricted by formal gateways leading to the ceramic workshops and botija (wine amphora) kilns, lagares (grape presses), bodegas (wine cellars), distillery, livestock corrals, and vineyards. However, excavations have revealed the habitual conflation of domestic and productive activities, despite the conceptual distinctions between the productive and residential zones in the hacienda inventories. Communal middens attracted trash from nearby activity areas and often yielded both discarded domestic and agro-industrial material in thin alternating strata. Discarded botija sherds, coarse minerals, wood scraps and metal hardware characterize recovered agro-industrial refuse in these middens. The strata containing domestic waste consist of sherds of majolica and coarse earthenware cooking vessels, glass bottle fragments and discarded faunal and botanical material. The occasional dark ash lens from the hearth or burned discarded organics is also characteristic of these contexts.

Provisioning and foodways practices were a crucial aspect of political aesthetics at the haciendas (Weaver et al. Reference Weaver, Muñoz and Durand2019). Foodways predominantly followed African culinary practices, combining provisioned meat with supplementary spices and flavours produced in slave gardens and usufruct fields. Access to specific goods was a critical component of cultivating difference within the enslaved communities and maintaining hierarchies. Gifting practices also constituted a specific aspect of these political aesthetics, as provisions of glassware and high-quality majolicas by the administrator probably constituted an important symbolic gesture that the administrators viewed as ingratiating them with the enslaved labourers.

Spatial segmentation followed the logics of an aesthetic informed by specific ideologies of discipline. Archaeogeophysics and excavation at San Xavier determined that around the turn of the eighteenth century, prior to the construction of the last Jesuit chapel in 1740, the hacienda underwent a radical spatial reorientation. Linear geophysical anomalies and excavated walls in front of the chapel suggest an earlier orientation of 35°, compared to the present north–south alignment of the hacienda house, chapel and modern town (see Weaver Reference Weaver2015, 208, 247, 428). As Nasca is a seismically active region with multiple earthquakes recorded around this time, it is likely that the Jesuit administration seized the opportunity to exert a new spatial order over the estate after a seismic event. While spaces were demarcated by hacienda architecture as conceptually distinct and purposed for specific activities, this segmentation of space was entangled by a police order that hierarchically privileged agro-industrial activities over the domestic. Similarly, the predominance of the chapels overshadowed the entire hacienda landscape, confusing the aesthetic boundaries between profane and sacred space within the distribution of the sensible (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. (Left) Ruins of Jesuit chapel of San Francisco Xavier de la Nasca (1745); (right) Ruins of Jesuit chapel of San Joseph de la Nasca (1744).

These chapels were built at a scale never seen on secular haciendas, and were unambiguously designed to index Jesuit piety and power (see Cushner Reference Cushner2002, 97). San Joseph's chapel's longitudinal dimension is 44 m, and San Xavier's measures 35 m; both were larger and grander than the diocesan parish church of El Ingenio, to which they were technically subservient. Structurally, each chapel could accommodate the large population of enslaved individuals, who congregated on days the chaplain visited, for mass, on feast days, the sacraments of baptism and marriage and funeral rites. The Jesuit hacienda administrators tended to be brothers rather than priests, and the duties of saying mass at the chapels and ministering to the enslaved population of the haciendas fell to contracted chaplains, hailing either from the parish of El Ingenio or farther abroad. Crown inventories detail the opulence of the chapels’ sanctuaries, with bejewelled and lavishly clothed statues, paintings and gold-leafed ornamentations, extravagant choirs with musical instruments, elaborately carved altars and well-furnished sacristies (ANC 1767a, ff. 233r–237r; 1767b, ff. 265r–268r). Jesuit religious art at hacienda and mission chapels was a point of contention within the order, in that it was given to ‘impress rather than teach’ (Cushner Reference Cushner2002, 118). Beyond their function as houses of worship, the large and imposing chapels aesthetically reinforced Christian discipline in the spatial and material conditions of the haciendas as constant reminders of the omniscient gaze of the divine. The belfry towers of these principal hacienda chapels, over 18 m tall, were visible from nearby annexes and their bells audible at even greater distances, disrupting any possibility of agro-industrial space beyond the sensorium of Christian discipline.

Roman Catholic chapel, or West African shrine?

The abundant demographic and cultural diversity among the enslaved populations of San Joseph and San Xavier must be taken into account to understand how the sensible was experienced and engaged at the estates. How was this diversity reflected in the potential for polyvalence, leading to disagreement and alternative distributions of the sensible within the hacienda aesthetic? As a consequence of such aesthetic disagreement, how were enslaved subjectivities co-produced through aesthetic engagement?

Jesuit administrators recognized differences among enslaved subjects and devised specific strategies for managing these populations. In his 1627 treatise on evangelization among enslaved Africans, the Jesuit Alonso de Sandoval ([1627] Reference de Sandoval and Vila Vilar1987) offers advice for considering ethnic differences in the evangelical approach. Sandoval's text was among the books of the administrator of San Xavier inventoried by the Crown in 1767, and was no doubt foundational in guiding indoctrination practices (ANC 1767b, f. 239r). The inventories also describe the enslaved communities at San Joseph and San Xavier's demographic diversity, with clear indications of a cosmopolitan and multilingual population and potentially originating from a variety of religious orientations. Supporting documentation suggests that many among the American-born enslaved population (criollos) had varying degrees of mixed African, indigenous and European ancestry. In addition, the 1767 inventory records 11 per cent (n = 33) of the male population were African-born, with casta [racio-caste] surnames suggesting affiliations with groups in Atlantic Africa (Table 1). Ethnic affinities for enslaved criollo men and women, and most African-born women, were often obscured in the records as they were typically given Christian surnames. Therefore, existing colonial documentation does not allow for a more refined breakdown of African versus criollo African-descendants. The eleven ethnonyms present in this inventory index origins ranging from Senegambia to Kongo/Angola.

Table 1. Counts for enslaved individuals listed in the 1767 slave inventories of San Joseph and San Francisco Xavier de la Nasca with African ethnonyms.

While documentation concerning casta affiliation during earlier periods at the haciendas is fragmentary, the property titles for San Joseph suggests that the first 15 African-born enslaved men acquired by the new estate in 1619 and 1620 were exported from the Upper Guinean coast or Cabo Verde (AGN 1620). Taken together with the later evidence, these records are reflective of the Peruvian trend away from the importation of individuals from ‘the Rivers of Guinea’ in favour of the Kongo and Bight of Benin by the eighteenth century (see O'Toole Reference O'Toole2012, 171; Wheat Reference Wheat2016). Given that the median age of the individuals listed in 1767 at San Joseph (where age was also recorded) is 55, the ethnonyms are likely to represent trends stretching back several decades (excluding an outlier recorded as 10 years old). This tendency is also evident in an earlier 1705 receipt for the purchase of eight enslaved individuals in Lima for San Joseph, all of whom had ethnonymic surnames: María Mina, Josepha Terranova, Parda Lucume [sic], María Lucume, María Rosa Chala, María Chala, Manuel Congo and Francisco Chala (AGN 1702–8, f. 16r). The names indicate that these six women and one of the two men originated from the Gold and Slave Coasts of Guinea, with the exception of Manuel Congo, who was probably shipped from Luanda. It should, however, be noted that enslaved people originating from the continental interior, as well as eastern or southern Africa, may also have acquired these ethnonyms at coastal West and Central African ports, and may not be affiliated with Atlantic cultural groups. The African-born population was probably religiously diverse: some may have been raised Muslim or Christian, especially those hailing from the predominantly Muslim Mandinka groups of the West African interior, or the Roman Catholic kingdoms of Angola and Congo, while others would have been practitioners of African traditional religions.

How did individuals of differing ethnic and casta origins experience the aesthetics of religious space of the hacienda chapels? The straightforward nature of the evangelization and indoctrination of enslaved subjects, evident in the material conditions of daily life, religious architecture and spatial organization of the estates, is complicated by public religious art. The chapels, built in the 1740s, with their extravagant adornments and verticality conform to stylistic choices of late baroque architecture in the Spanish colonies, combining the flourishes from older European baroque prints and source books that circulated in the region with newer classically inspired iconography (Rodríguez-Camilloni Reference Rodríguez-Camilloni, O'Malley, Bailey, Harris and Kennedy2006, 254). While art historians identify the baroque in Latin America as a projection of a Christian European universalist sense (see Cushner Reference Cushner2002, 112), religious art on Jesuit haciendas and missions was typically produced by local artists working through European forms (Bailey Reference Bailey1999; Cushner Reference Cushner2002, 118). It was this adaptability to local cultural sensibilities that allowed a specifically Andean form of baroque art and architecture to flourish at Jesuit haciendas, missions and urban churches in the Andean region from the 1660s well into the mid eighteenth century (Bailey Reference Bailey2010).

Although the artisans who produced the plaster-moulded sculptural friezes at both chapels are not named in extant documentation, the attempt to represent Christian ideas for the African-descended congregation is readily apparent, whether that meant making use of local enslaved craftspeople, or bringing African-descended artists from urban centres like Lima. Plaster-moulded sculptural friezes at both chapels embody the polysemy that typified life at the ethnically plural estates, and resonate with the aesthetics of distinct African cultural and artistic traditions (see also Weaver Reference Weaver2018, 121). Architect Sandra Negro (Reference Negro, Negro and Amorós2014) suggests the friezes were intended as tools of indoctrination and are principally reflective of Jesuit theological and ideological considerations for evangelization and the place of slavery within ‘God's Plan’. The contrasting extremes of life and death, the angelic and the grotesque demonic, remind the observer of universal original sin and human mortality, and also the promise of eternal life. However, by placing these materials within the aesthetic field, the polyvalence of such sculptural representation emerges as the politics of potential contentions among multiple hierarchical, but coeval, aesthetico-political regimes.

At the San Xavier chapel, a pair of moulded plaster sculptural friezes on the pilasters of the triumphal arch represent an example of the politics of aesthetic contentions (Fig. 4). The frieze depicts a classical urn with a flowering plant covering the genitals of a grotesque human form with an extended tongue, positioned below an equal-armed cross. Flowers cover the breasts and stomach of the individual, who appears to be female and pregnant. Two zoomorphic dog-headed serpentine bodies emerge from the plant's vines, the creatures’ fangs agape at her cheeks. The similarities to northern European Green Man imagery appropriated by continental Jesuits is readily apparent, and circulating prints likely served as an archetype. The artist's intent is unknown, but the imagery might have evoked an unusual interpretation of the Fall of Man for the Catholic observer: the pregnant Eve bringing original sin upon her descendants, redeemed through Christ's sacrifice on the cross.

Figure 4. Moulded plaster sculptural frieze on a pilaster in the Jesuit chapel at San Xavier, with detail.

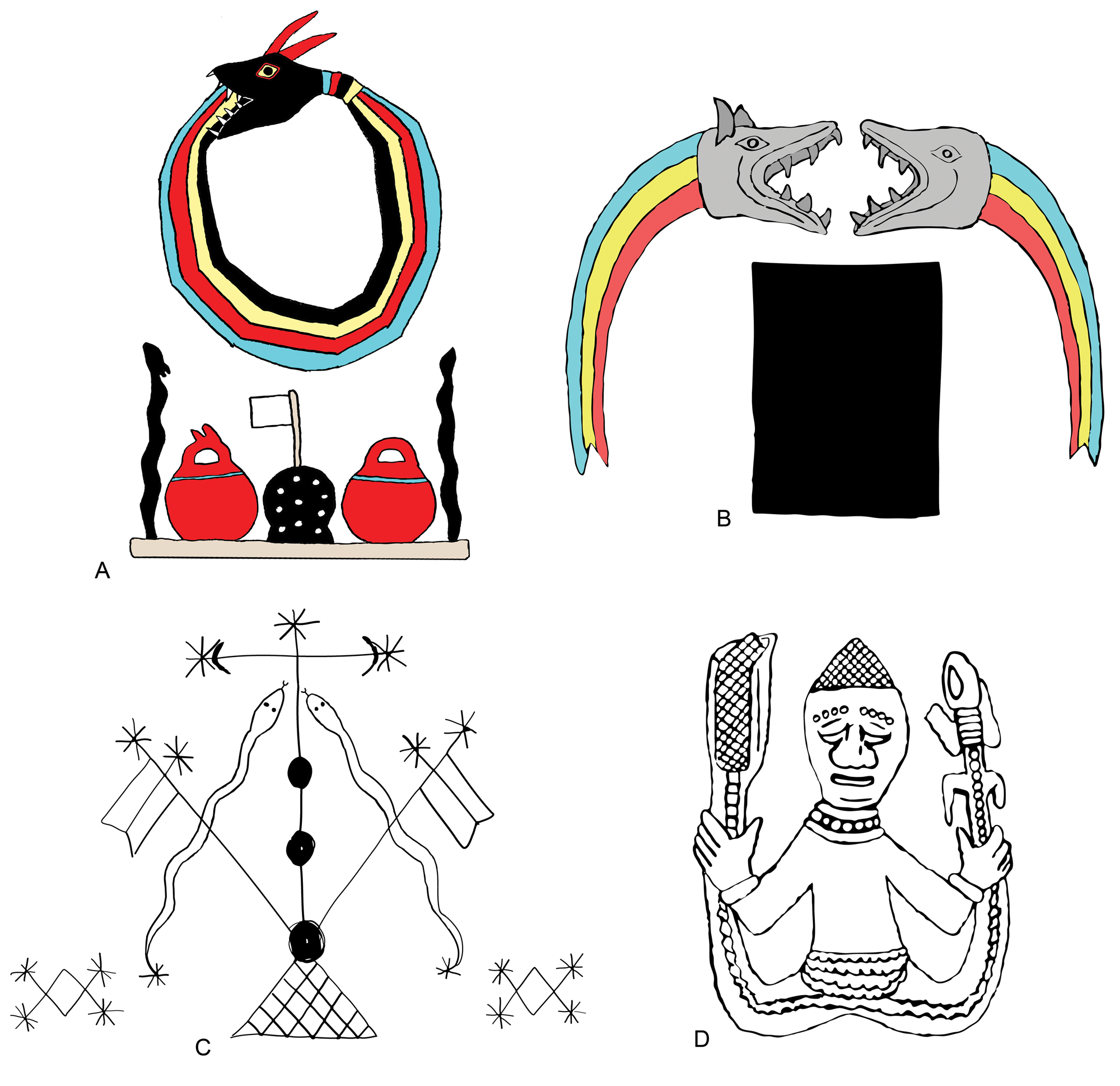

Regardless of the sculptors’ intent or influences, enslaved worshippers probably brought their own aesthetic conventions to the interpretations of the chapels’ art, and this image in particular. From a pragmatic frame, the same polyvalent signs are capable of indexing multiple referents, and discourse among enslaved individuals is likely to have produced new meanings, some of which can only be partially conceived from the material remains. How, for example, might Pedro Pablo Terranovo or Francisco Popo, individuals residing at San Xavier in 1767, have understood this frieze? The terranovo ethnonym (interchangeable with lucumí) signals origins in Yorubaland, and Popo was probably born in the region of the Bight of Benin (potentially a Fon-Ewe speaker from Togo or Benin). While pythons and dogs are associated with shrines and ritual activity across West Africa and among Bantu peoples (see Schoenbrun Reference Schoenbrun, Roddick and Stahl2016; Stahl Reference Stahl, Mills and Walker2008b), Yoruba cultural observers may have recognized the pair of serpentine creatures as the Rainbow Serpent, known as Oṣùmàrè in the Yoruba religious tradition. Alternatively, Yoruba observers might have associated the serpent bodies with the female orisha Oshun and dog heads with the male deity Ogun. Fon-Ewe speakers, especially coming from the eighteenth-century kingdom of Dahomey, may have recognized the serpents as Dan Ayidohwedo (see Herskovits & Herskovits Reference Herskovits and Herskovits1933; Norman & Kelly Reference Norman and Kelly2004), the dualistic python deity responsible for creation and procreation. Dahomey drew its name from this deity, and the kingdom's emblem featured a horned version of this ‘Rainbow Serpent’ consuming its own tail in a representation of the life-cycle, creation and destruction (Fig. 5a). Alternatively, the deity is depicted as two facing serpents, horned male and hornless female aspects, poised to consume each other (Fig. 5b). Associated with symbols of fertility and life, such as plant roots, the Rainbow Serpent links the world of the living with the watery world of the ancestors and the dead among several Atlantic-African traditions. In New World vodou, the Rainbow Serpent appears as the loa Damballah, also depicted as a pair of facing snakes bisected by a cross (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5. (A) Representation of the male Rainbow Serpent, Dan, and ritual paraphernalia on a Dahomeyan appliqué cloth produced between 1708 and 1740, under the rule of King Agaja (see Herskovits & Herskovits Reference Herskovits and Herskovits1933: 74); (B) Bas-relief of Dan Ayidohwedo, male and female aspects of the Rainbow Serpent, above a doorway at the Houemou Agonglo Temple, Abomey, Benin (date unknown); (C) Veve for the Haitian Vodou loa Damballah; (D) Detail of a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century representation of a mudfish- and crocodile-legged figure (possibly representing the water Yoruba deity Olokun) carved on an ivory armband from Owo, Nigeria. The object is located at the National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen (L2007.89.2). (Line drawings by author.)

Across sub-Saharan Africa, especially among people of West Africa and Kongo, serpent imagery is associated with water deities, and the central figure's pose, with outstretched arms grasping the serpentine beasts, resembles representations of the Yoruba Olokun and other water spirits (Fig. 5d). The San Xavier figure's extended tongue is another point of spectator disagreement, signifying death in Western imagery, but among West and Central African traditions, danger, consumption, or oration—among the Yoruba, potentially curses or ‘hot’ speech (Blier Reference Blier2015, 188). These points of reference between specific African imagery and the San Xavier frieze are not to suggest any fixity in meaning among the enslaved community or affiliation with any single pantheon, but rather a potential resonance with a constellation of sub-Saharan belief systems and aesthetic traditions that incorporate serpent imagery, as well as an association of serpents with feminine aspects of divine water spirits. The signs’ valence is multiple, potentially representing both the Fall of Man, the baroque juxtaposition of life and death and the promises of eternal life through divine covenant, and a supernatural bringer of life and fertility, through whom one accesses the ancestors.

The potential eighteenth-century association of the San Xavier frieze with a water spirit is aided by ethnographic analogy to local cultural references. Afro-Nascan folklore and literature often reference female water spirits—sirenas [mermaids]—especially at the several spring-fed lagoons located in the Ingenio and Grande Valleys (e.g. Martínez Reference Martínez1977). Despite these contemporary cultural examples, activists and scholars have often pointed out the bias in popular discourse against the recognition of Africanisms in Afro-Peruvian Catholic devotion (e.g. Rocca Reference Rocca Torres2010). Recognizing the potential for eighteenth-century ecclesiastical art in the historical development of Afro-Peruvian religiosity is particularly important for contemporary discourse in Peru regarding broader African contributions to Peruvian culture.

Suggesting an association between a New World and African phenomenon is a challenging task, requiring a high level of historical specificity (DeCorse Reference DeCorse and Singleton1999; Fennell Reference Fennell2007). However, an archaeological aesthetic approach is not about uncovering the essential ‘Africanity’ that informed the creation of objects (see Yelvington Reference Yelvington2001), but understanding how the material was charged with multiple, sometimes contentious, meanings through aesthetic activation and engagement. Many of these meanings are lost to the archaeologist, but understanding the potential for aesthetic disagreement rather than specific meaning is the goal. African ritual in diasporic contexts has been interpreted as an important form of resistance (e.g. Ruppel et al. Reference Ruppel, Neuwirth, Leone and Fry2003) or memetic (e.g. Argenti & Rötschenthaler Reference Argenti and Rötschenthaler2006), and recent attention to ritual by historians and archaeologists has illuminated its materiality (Ogundiran & Saunders Reference Ogundiran and Saunders2014). However, an aesthetic archaeological approach untangles the political import of art that lends itself to slippery meanings, redistributing the sensible when viewed from the distinct sensory logics that disrupt the aesthetico-political regime.

The possibility for public religious art to signify alternative referents for various cultural observers offers a disruption to the dominant distribution of the sensible, but the politics of the interjection or attribution of such referents to the given signs is not straightforward. The Jesuit chapels of the Nasca haciendas are not unique, but represent a baroque that emerges at the nexus of multiple aesthetics—recognized by architectural and art historians as a specific form of Andean hybridity (Bailey Reference Bailey2010), in this case referencing Atlantic-African ritual and political aesthetics. Does the possibility of spectator disagreement (Rancière Reference Rancière and Elliot2009) in the aesthetic experience subvert Catholic doctrine, transforming the chapel into a West African shrine? Unfortunately, the full range of past meanings of these signs is not accessible, but it is not enough simply to call them syncretic or hybrid. While hybridity is common enough in colonial, and particularly Jesuit, religious art that such deviations from orthodoxy were probably viewed as an evangelical tool, the reception of such signs and their referents is not as easily controlled. Meanings are tangled in multiple distributions of the sensible, distinct ‘ways of framing a sensory space, of seeing or not seeing common objects in it, of hearing or not hearing in it subjects that designate them or reason in their relation’ (Rancière Reference Rancière and Corcoran2010, 92). It is also important to recognize that the aesthetic experience of the frieze was not limited to the visual—how would standing in the crowded nave during a mass, the friezes illuminated by candlelight, incense wafting, violin and organ music reverberating from the choir loft, and the liturgy of the Latin Mass echoing from the cedar pulpit, have transmuted the visual affect? It is possible that for many enslaved worshippers the friezes referenced both African traditional and Roman Catholic cosmology. Nevertheless, the very potential for multiple, contested significations points to ambivalence as a possible political valence—for enslaved actors to produce and reproduce meaning in a space designed to forge a particular type of enslaved subject, one disciplined by Christian virtue.

Aesthetics of production, production of aesthetics

A specific spatial and temporal segmentation of the sensorium of daily life ordered the hacienda aesthetic. This segmentation was largely the result of administrative design and followed environmental cycles. At the Jesuit vineyards of Nasca, production followed the diurnal cycle of habitual tasks and movements across hacienda spaces, fields and production sites, and the annual cycle of agro-industrial labour, from pruning and planting to harvest, vinification and distillation. These Jesuit haciendas were intended to fulfil a dual productive destiny, to cultivate enslaved Christian subjects, who themselves cultivated the grapes, and manufactured the products of the estate—wine, brandy, vinegar and raisins—and the packaging for such produce, the botijas. An examination of hacienda ceramic manufacture by enslaved botija potters (botijeros) considers material aesthetic culture at the nexus between top-down and bottom-up processes. How were enslaved subjectivities shaped by this aesthetic experience, and did they themselves participate in the generation of new and alternative aesthetic experience? The resultant production is one potentially located at the political disagreement between the logic of one aesthetic field and another.

The biopolitics of the dominant distribution of the sensible was policed to classify bodies by a specific and ordered aesthetic that not only determined how these bodies were used to perform labour, but also social standing in the enslaved hierarchy and monetary value as human commodities. Enslaved life at the Nasca haciendas was highly structured by a distribution and hierarchy of subjectivities, including gender, casta, specialized knowledge and a strict division of labour. Despite the default of female-produced pottery in West Africa (Burns Reference Burns1993), enslaved botijeros in colonial Peru were exclusively men and did not necessarily have much experience with African techniques of ceramic production, but were highly valued. While a young female field hand cost little more than 100 pesos, a botijero could fetch over 800 (Cushner Reference Cushner1980, 119). At such an investment for the estate, it would be more difficult for such skilled labourers to purchase their own freedom, although they were placed near the top of the administrative hierarchy. In 1620, San Joseph acquired its ceramics production workshop along with the enslaved botijero Domingo de Guelua [sic. Huelva] and six enslaved Senegambian assistant botijeros: Diego Bran, two men named Francisco Bañol, Bernal Balanta, Francisco Bran, and Gaspar Bran (AGN 1620, f. 302r). During the eighteenth century, San Joseph and San Xavier had less than a dozen men each working in ceramic production out of the total enslaved population of nearly 600.

At the height of production in the eighteenth century, San Xavier alone annually produced between 6000 and 15,000 botijas of wine and brandy (Cushner Reference Cushner1980, 126, 145), necessitating the extraordinary production of botijas. The 1767 inventories are explicit in listing the ceramic production facilities together, and note eight throwing wheels at each hacienda, with three kilns at San Xavier and four at San Joseph (ANC 1767a, f. 272v; 1767b, f. 245v). Geophysical and archaeological evidence, however, reveals that there were considerably more kilns and ceramic production facilities throughout the haciendas’ histories, and that there were several distinct production sites (Weaver Reference Weaver2015, 183–242). Kilns may have had use-lives necessitating their continual construction over the course of three centuries of production. It is noteworthy that all of the ceramic production was restricted to the cores of the principal estates. When the Hacienda La Ventilla was purchased as an annexe of San Joseph in 1706, it was acquired with a kiln, but although vinification and distillation was carried out at the complex, ceramic production was moved to San Joseph (AGN 1706).

Given the scale of production, it is not surprising that botijas are the most common ceramic type found on the sites of the haciendas, and between San Xavier and San Joseph nearly 11,000 botija sherds have been recovered from excavated contexts. Although the botija's wheel-thrown amphora form is part of a long-standing Mediterranean ceramic tradition, the decorative attributes on these vessels seem to emerge from a dual parentage. The Nasca botijas feature various decorative techniques, including brushing, cord impressions, finger markings and combing—typically motifs composed of annular straight and wavy lines (Fig. 6). The potters drew upon Mediterranean aesthetics and techniques, converging with Atlantic-African aesthetics and decorative traditions. The wavy motifs and comb-dragged multi-banded incisions all have resonance with Atlantic-African antecedents, and are completely absent from native Andean traditions. Comb-dragged and wavy line motifs on the botijas were prevalent across West Africa since at least the thirteenth century (Manning Reference Manning2011), and annular wavy bands, in singular or multiple registers, have a broader application in ceramic and wooden vessels associated with ritual activity, especially palm-wine vessels among Kwa and Western Bantu peoples (Blier Reference Blier2015, 138). Although these decorative motifs are not easily attributed to a specific ethnic group, in the context of the Nasca haciendas, their use was certainly polyvalent and consisted of contributions by multiple cultural actors.

Figure 6. Drawings reconstructing the decorative applications and motifs on the seventeenth- to eighteenth-century botijas from the Hacienda San Joseph de la Nasca.

Motifs on the botija setters also resonate with African aesthetics—particularly those with knotted string cord roulette impressions. These wheel-thrown coarse earthenware tools were created by enslaved craftsmen for use in firing during pottery production and for setting botijas upright during alcohol production. Cord roulette impressions (see Haour et al. Reference Haour, Manning and Arazi2010) were introduced to West Africa from the southwest Sahara via the Niger Bend from the late Neolithic to Late Iron Age (Gosselain Reference Gosselain2000; Livingston Smith Reference Livingston Smith2007; Manning Reference Manning2011, 82; Mayor Reference Mayor2010, 29). In West Africa, this decorative technique often occurs in an inferior register on ritual vessels, especially near their rounded bases (Soper Reference Soper1985). A surface-collected sample of 22 setter sherds from Hacienda La Ventilla demonstrates the range and variability of both form and decoration (Fig. 7). In contrast to the botijas, which as products of the estates conformed to a certain uniformity, the setters are much more idiosyncratic, loosely fitting into three morphological ‘types’, with a variety of pinched/finger impressed and twisted and wrapped cord roulette patterns. This demonstrates that among the range of possibilities, the potters had the liberty to elaborate these tools with their personal preferences.

Figure 7. Botija setters recovered in surface collection (n = 22) from the site of the Hacienda La Ventilla, with three distinctive forms and three principal decorative motifs. Form types and decoration are not exclusive, as indicated in the chart above. (I) cord roulette decoration (50 per cent); (II) digital impressions at the base (13.5 per cent); (III) smoothed and brushed surface (36.5 per cent); (A) form with a direct wall, thinned rim and partially rounded lip (55 per cent); (B) direct walled form with rolled rim and flattened lip (13.5 per cent); (C) form with everted rim profile and rounded lip (31.5 per cent).

Of particular note is the specificity of the decorative motifs on the botijas and setters of the Nasca haciendas, in comparison with other vini-viticultural estates in colonial Peru. The early historical archaeological interventions of Prudence Rice's Moquegua Bodegas Project in the 1980s generated ample data regarding agro-industrial ceramics related to wine and brandy production, relevant for comparison here. However, none of the botijas recovered from the extensive survey and excavation project in Moquegua's Osmore Drainage, 500 km southeast of Nasca, bear the combed or annular wavy motifs, and none of the Moquegua botija setters are decorated with cord roulette or digital impressions (Prudence Rice pers. comm., 2014). This aesthetic difference may stem from differences in productive scale and worker demography: Jesuit properties in Nasca represent large vineyards, worked predominantly by enslaved African-descended labourers, owned by a single institution (the Society of Jesus). The vineyards of Moquegua tended to be smaller-scale and primarily employed indigenous and mestizo wage labourers, with relatively few African descendants (Rice Reference Rice2012; Smith Reference Smith1997).

Unlike colonowares or other examples of hybrid African/European/indigenous household ceramics made elsewhere in the Americas, the Nasca botijas and setters are industrial Mediterranean forms decorated with motifs that resonate with Atlantic-African ritual pottery. These two ceramic types, although distinct, were made by the same group of enslaved potters at the Jesuit estates of Nasca, but index different modes of signification within the same economy of signs and the same mode of production. Excavated evidence suggests that the botijas and their motifs changed little on the haciendas during the course of a century and a half (1620–1767), while setters seem to represent something unique for each potter. It is also unclear what effect the early influence of Senegambian potters may have had on later production, as hacienda demographics shifted toward criollos and Lower Guinean and West Central Africans. Perhaps for some, a life prior to captivity was indexed in these materials, and for others, they represent relatively stable signs (Connerton Reference Connerton1989). The motifs suggest that although such aesthetic production became rooted in habit and hacienda tradition, it was largely controlled by enslaved ceramicists.

It is significant that the setters—ordinary tools made and used by enslaved workers—were carefully decorated, and that these decorations were not uniform. After I presented my findings at a 2017 workshop, art historian Alejandro de la Fuente specifically commented on these setters in an essay on the history of Afro-Latin American art. For de la Fuente (Reference de la Fuente, de la Fuente and Andrews2018, 358), these objects ‘open up new and exciting opportunities for further research into the aesthetic sensibilities and interventions of African slaves’. What does it mean that these setters could be considered art? Rancière's essay ‘On Art and Work’ offers useful commentary on the distribution of occupations (2004, 40–41). The category of human production that constitutes art is bounded by the specificity of the time and place of its making, as are the ordinary goods made by labourers whose time and space belong to a specific mode of production. Works like the setters, produced under the temporal and spatial regime of slavery, pose a rupture not only in the dominant distribution of the sensible, but also potentially disrupt the early modern Western aesthetics of production, through the dislocation of art/work from the proper time/place. By recognizing the artistic interventions of labourers, we have here recast enslaved craftsmen as artists. While such a transgression of categories would not have been recognized in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the effect of enslaved agents actively producing artwork beyond the aesthetic control of the hacienda administration would have marked a significant ability to control and contribute to the production of their own aesthetic worlds.

Final remarks

Devising and deploying tools that allow for a nuanced understanding of the political import of everyday activities in the context of early modern slavery remains a challenge for archaeologists. It has been my goal to introduce the utility of a Rancièrean approach to aesthetics and politics to archaeological thinking, and illustrate its efficacy for navigating cultural communication and power, materialized tensions and contradictions, and open up possibilities for recognizing ambivalence in past political discourse. The case study of slavery at the Jesuit vineyards of Nasca demonstrates the value for shedding light on the co-production of enslaved subjectivities through the process of disagreement in the distribution of the sensible. By considering the materialized politics of the aesthetics of space and the built environment, hierarchical practices, public religious art and the production of slave-made ceramics, it is possible to approximate power and subjectivity in the everyday lived experience. In particular, by placing the San Xavier serpent frieze within an aesthetic field it is possible to recognize the sensible politics of polyvalence, instead of focusing on the art's hybrid nature. Rather than concentrating on the specific, and sometimes unknowable, meaning imparted by the actor(s) involved in the creation of an object, instead placing the material within the aesthetic field reveals the potential for aesthetic disagreement.

The hierarchical and spatio-temporal aesthetics of production that act on enslaved bodies in specific, habitual and internalizing ways also allow for enslaved agents to disrupt the dominant distribution of the sensible and produce meaning in the aesthetics of the quotidian. This is evident in the aesthetics of botijas as commodities that bear signs of corporate and habitual identity and setters as both tools and works of art. Rancière is useful in thinking about the sense and sensibilities of material culture in ways that push archaeologists to consider the spaces between aesthetic logics of political practice as well as the political logics of aesthetic practice. Through an archaeology of the aesthetic, we can gain a more nuanced appreciation for the complexity of everyday engagement with the material world, and the fields that filter what is perceivable through the senses.

Acknowledgements

I would like first to express my appreciation to Adam Burgos for introducing me to the political philosophy of Jacques Rancière in 2014, during a workshop at the Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities at Vanderbilt University. Working through the ideas presented here was made possible by a post-doctoral fellowship at the Stanford Archaeology Center, Stanford University. Field research has been supported by the Social Science Research Council (2012), Robert Penn Warren Center for the Humanities (2016), Mellon Partners for Humanities Education (2016–18) and Stanford Archaeological Center (2018–19). Thank you to the two anonymous peer reviewers for their insightful commentary, as well as the helpful discussion and suggestions of Meghan Cook Weaver, Federico Pagello, Matthew Velasco and Ian Hodder. I also owe a debt of gratitude to the Peruvian Ministry of Culture, the communities of El Ingenio, Changuillo and Palpa, as well as the entire Proyecto Arqueológico Haciendas de Nasca family.