No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

§1. Family, Early Life and Character

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Introduction

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Royal Historical Society 1939

References

page xi note 1 At the end of 1178 he wrote, ‘septuagesimum annum transgressus sum’ (below, p. 188). For convenience we calculate his age throughout as though he were born in 1105.

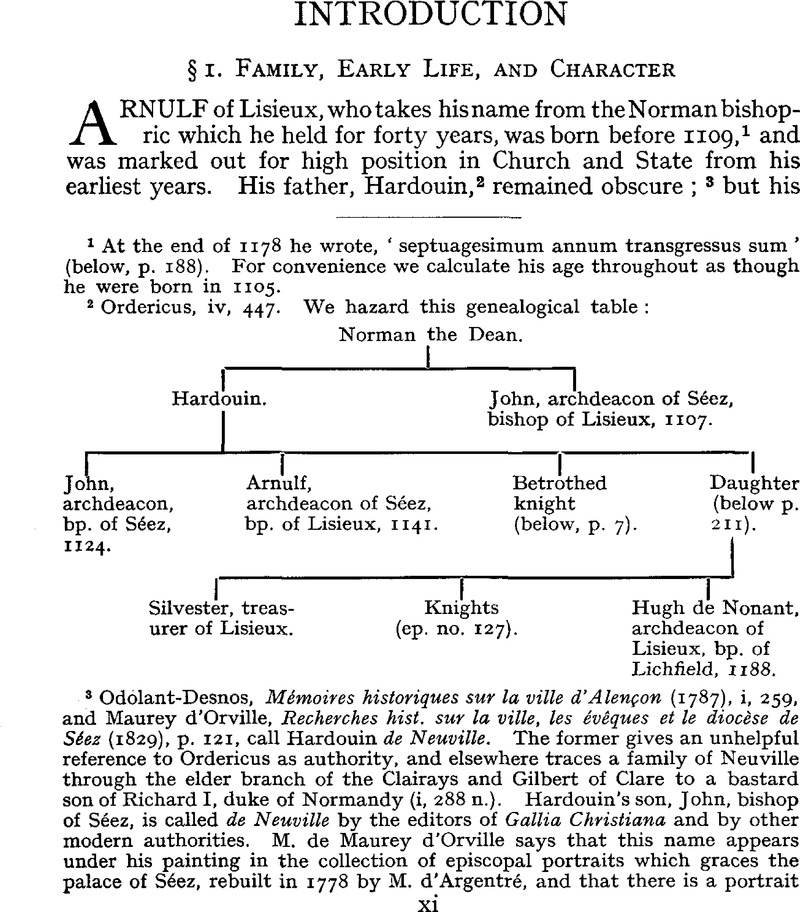

page xi note 2 Ordericus, iv, 447. We hazard this genealogical table:

page xi note 3 Odolant-Desnos, Mémoires historiques sur la ville d'Alençon (1787), i, 259Google Scholar, and d'Orville, Maurey, Recherches hist, sur la ville, les évêques et le diocèse de Séez (1829), p. 121Google Scholar, call Hardouin de Neuville. The former gives an unhelpful reference to Ordericus as authority, and elsewhere traces a family of Neuville through the elder branch of the Clairays and Gilbert of Clare to a bastard son of Richard I, duke of Normandy (i, 288 n.). Hardouin's son, John, bishop of Seez, is called de Neuville by the editors of Gallia Christiana and by other modern authorities. M. de Maurey d'Orville says that this name appears under his painting in the collection of episcopal portraits which graces the palace of Séez, rebuilt in 1778 by M. d'Argentré, and that there is a portrait of John in the chateau of Neuville, near Séez (op. cit., p. 120). Historical traditions of this sort which can be traced back beyond the Revolution are always worthy of attention, and it is just possible that Hardouin was lord of Neuville. Certainly one son of Hardouin was betrothed to a girl of noble stock (see below, p. 8). Toponymics, however, in ecclesiastical dynasties do not necessarily imply feudal lordship.

page xii note 1 Or Norman, dean (of Séez). Ordericus, iv, 273.

page xii note 2 Ordericus, iv, 273–5.

page xii note 3 Round, E.H.R., xiv, 427.Google Scholar

page xii note 4 Gerald of Wales (‘Gemma Ecclesiastica’), ii, 304, ‘Unde papa Alexander III factum hoc, ut fertur, verbum emisit: “Filios episcopis Dominus abstulit, nepotes autem diabolus dedit”.’

page xii note 5 See examples given by Stubbs, Diceto, p. xxvii.

page xii note 6 Op. cit., ii, 359, ‘Non dicimus episcopos non salvari, dicimus autem difficilius ipsos his diebus quam alios salvari’. Compare Caesarius of Heisterbach's story of the clerk at Paris who could believe all things except that any German bishop could ever be saved (Dialogus miraculorum, ed. Strange, J. (Cologne, 1851), i, 99).Google Scholar

page xiii note 1 Round, , op, cit., p. 428.Google Scholar

page xiii note 2 Yet one of his charges against Gerard, bishop of Angoulême, was the advancement of his nephews, Invectiva, cap. 1.

page xiii note 3 See below, p. 201.

page xiii note 4 Silvester, treasurer of Lisieux, witnesses two charters of Becket, 1162–4 (Round, , Calendar, p. 486Google Scholar), and is found in correspondence with John of Salis bury and Becket (Materials, v, 113 and 194Google Scholar). Hugh was one of Becket's eruditi, as was another of the archdeacons of Lisieux, Gilbert de Glanville (see Bosham's character sketches of them, Materials, iii, 525–6Google Scholar). Arnulf probably sent them to Canterbury for their education, and Hugh made his peace with the king during the struggle (ibid.).

page xiii note 5 See below, pp. lvi, seqq.

page xiii note 6 See below, p. 57.

page xiii note 7 Deshays says, on the authority of Herman, ‘the historian of the diocese of Séez’, p. 199Google Scholar, that Arnulf was treasurer of Bayeux for a short time before becoming archdeacon of Séez (Deshays, Noël, Mémoires pour servir à l'histoire des évêques de Lisieux (1763)Google Scholar, ed. in H. de Formeville, Hist, de l'ancien évêchécomté de Lisieux (Lisieux, 1873), ii, 47).Google Scholar

page xiv note 1 See below, pp. xxxiii, seqq.

page xiv note 2 The earliest is dated 1144.

page xiv note 3 For Geoffrey, see H.L., xiii, and Clerval, A., Les écoles de Chartres au Moyen Age (Paris, 1895), pp. 153–5.Google Scholar

page xiv note 4 Biographical information in Arnulf's preface.

page xiv note 5 Ordericus, iv, 323–4.

page xiv note 6 Ibid., iv, 471.

page xiv note 7 He later mentions Henry's gift to the church on this occasion; see below, p. 56.

page xiv note 8 Cap. 2.

page xiv note 9 See below, p. 15.

page xiv note 10 Arnulf wrote a laudatory poem on Henry (no. 2).

page xv note 1 Apart from having advanced the careers of members of the family, Henry had also granted revenues to the church of Seez in 1126 (Ordericus, iv, 471), and in 1131 (Haskins, C. H., Norman Institutions (Harvard, 1918), p. 302).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

page xv note 2 See Invectiva, cap. 6, and below, p. 56. He also wrote a complimentary epitaph for his tomb (poem no. 9).

page xv note 3 ‘Mirum est, Ernulfe, qua fronte nunc persequeris mortuum quem uiuum semper adorasti, sicut fratres tui, et cognatio uniuersa, qui te et totum genus tuum erexit de stercore. Mirum est qua impudencia sic mentiris, nisi quia totum genus tuum loquax est et sublimari meruit uite maculis et arte et audacia mentiendi. Hiis artibus apud Normannos estis insignes' (John of Salisbury, Historia pontificalis, ed. Poole, R. L. (Oxford, 1927), p. 87Google Scholar). John, of course, may well have barbed the arrow.

page xv note 4 In the preface to his Invectiva, which was written in the summer of 1133, Arnulf says, ‘Sed quia me in Italiam desiderata diu Romanorum (al. Romanarum) legum studia deduxerunt, …’ The editors of the Gallia Christiana, xi, 774Google Scholar, interpret this as meaning that Arnulf went to Rome to study canon law. Deshays, , op. cit., ii, 47Google Scholar, is vaguer but more comprehensive. He wrote, ‘Il entreprit dès avant 1133, le voyage de Rome, pour se former à la science ecclésiastique, et puisser là, comme dans sa source, la connaissance des lois romaines’. These commentaries raise two points: (1) Did Arnulf go to Rome? and (2) What did he study in Italy?

If Arnulf did not go to Italy before 1130 it is unlikely that he went to Rome, for it was usually in the possession of the anti-pope, and certainly a residence at Rome is not necessary to explain any familiarity with Pope Innocent II, who between 1130 and 1136 had his Italian head-quarters at Pisa. Nor does Arnulf reveal in his Invectiva any intimate knowledge of Roman events. Indeed, when we compare his vivid descriptions of a later schism, which he wrote in Normandy, with this work which was written in Italy, it is apparent that Arnulf had mainly inferior second-hand knowledge of the great events of 1130–4. Dieterich, introduction to Invectiva, p. 83Google Scholar, makes the reasonable suggestion that Arnulf was at Bologna.

‘Romanorum (or Romanarum) legum studia’ is certainly a vague phrase; but Arnulf became an accomplished lawyer, and it was usual for archdeacons to spend some of their time engaged in practical study. The phrase must certainly be understood in a concrete sense, and, while it seems more appropriate to civil than to canon law, it was perhaps used to cover both. Unless, however, Arnulf almost completely neglected his archidiaconal duties, there seems to be hardly time for a full study of both kinds of law at this stage.

page xvi note 1 H.F., xv, 583.Google Scholar

page xvi note 2 Ibid., xv, 637.

page xvi note 3 Cap. iv, 5.

page xvi note 4 Theobald and Geoffrey founded the abbey of l'Aumône in 1121 (G.C., viii, instr. col. 419), and Arnulf knew the fourth abbot, Philip (see below, p. 15).

page xvi note 6 Arnulf was a benefactor of the monastery of Val-Richer near Lisieux, and had many ties with the abbey of Mortemer, where he wished to retire in 1166 (see below, p. xlv). He was a friend of Abbot Richard de Blosseville (ep. no. 117), and in MS. Paris, B.N., latin 2594, fo. 5, the sermon In Annuntiatione Gloriosae Virginis Mariae (no. 4) has the title, ‘Expositio domini Arnulfi, Lexouiensis episcopi et doctoris clarissimi, directa ad A., cantorem Mortuimaris’. See also below, p. xxxii.

page xvii note 1 Ep. no. 17, bk. II, M.P.L., clxxxix, 208Google Scholarseqq.

page xvii note 2 Ep. no. 26.

page xvii note 3 Stubbs thought that he was born between 1120 and 1130 (Diceto p. xx). It seems doubtful whether Stubbs' interpretation of this letter of Arnulf is correct, for he does not seem to have realized how much older Arnulf was than Ralph. If we take Stubbs' outside year for Ralph's birth, 1120, the earliest year in which we can imagine him at Paris is 1134, when he would be fourteen years old, and Arnulf would be twenty-nine, when Ralph would be at the beginning of his studies and Arnulf at the end. A much more likely reconstruction of their meeting is that Ralph had visited the church of Séez or Lisieux on a holiday from Paris with a letter of introduction, and Arnulf's vague words give as much support to this theory as to the other. It is also perhaps not without significance that Arnulf informs Ralph in 1160 of the death of ‘their common friend’ Ralph de Fleury, who is noticed as a canon of Lisieux in 1148. It is true that Arnulf's words of friendship are more suitable to an equal than to a protégé; but in 1160 both were quite mature, and the friendship had probably developed. Unless the date of Ralph's birth can be put even further back, I am inclined to hold that he visited Arnulf when bishop of Lisieux, i.e., after 1141.

page xviii note 1 See below, pp. 55–9; Torigni, p. 145; John's instrument is printed, G.C., xi, 160.Google Scholar

page xviii note 2 Torigni, p. 145.

page xviii note 3 G.C., viii, 420–1.Google Scholar

page xviii note 4 Ibid., xi, 858.

page xviii note 5 Below, p. 56.

page xviii note 6 Torigni, , p. 123Google Scholar; Paris, Matthew, Chronica Majora (Rolls Series), ii, 158Google Scholar; Dugdale, W., Monasticon (ed. J. Caley, etc., 1846), vi. (i), 91Google Scholar; V.C.H. Cumberland, vol. ii.

page xviii note 7 E. Martène et U. Durand, Vet. Scriptorum … Ampl. Collectio (Paris, 1729), vi, 231.Google Scholar

page xviii note 8 Epp. nos. 122, 125, etc.; 23 and 84. For Peter's career and for the dispute over his connexion with St. Victor, see below, p. 136, note a. Arnulf, however, may only have become acquainted with him in 1169, when Peter had an unfortunate experience in the Henry-Becket negotiations (Materials, vii, 78–82 and 198–202Google Scholar, and i, 73; Gervase, p. 212). Peter had also been at Chartres.

page xviii note 9 Printed in L. V. Delisle's edition of the Chronique de R. de Torigni (Soc. de l'hist. de Normandie, 1872–1873), i, 107Google Scholar. There is no reference to any schooling.

page xix note 1 See below, pp. xxxiii seqq.

page xix note 2 Below, p. 85.

page xix note 3 His sermon in synodo (no. 3) and no. 4 (see p. xvi, n. 5) are of a theological nature, and of his letters nos. 5 and 12 should be noticed.

page xix note 4 See above, p. xv and n. 3.

page xix note 5 The provenance and date of this council have aroused much speculation. Round, J. H., Geoffrey de Mandeville, pp. 250Google Scholarseqq., and Mlle. Chartrou, Josèphe, L'Anjou de 1109 à 1151 (Paris, 1928)Google Scholar, Appendix II, discuss the problems in some detail, and Dr. R. L. Poole, Historia Pontificalis, Appendix VI, settles the question decisively in favour of the General Council held at the Lateran in the spring of 1139.

page xix note 6 Torigni, , p. 142Google Scholar; Annales Uticenses in Ordericus, v, 161Google Scholar; cf. below, pp. 181, 190, 198 and 209.

page xix note 7 Ibid., p. 142; Ordericus, v, 132.

page xx note 1 Letters of Bernard and Peter, H.F., xv, 582 and 637Google Scholar; see below, p. 209.

page xx note 2 Below, pp. 181, 190 and 198. Deshays (op. cit., ii, 49), says that Arnulf went to Rome to prosecute his case. The only evidence for this appears to be the rhetoric of St. Bernard, ‘Suscipe Lexoviensem episcopum … et remitte eum in benedictionibus dulcedinis’ (H.F., xv, 583).Google Scholar

page xx note 3 See note 1.

page xx note 4 See below, p. 209.

page xx note 5 A charter granted by Arnulf in 1142 is dated by Stephen's reign (quoted by Haskins, Norman Institutions, p. 130, n. 23Google Scholar), which shows that the lack of recognition was mutual. Arnulf, however, dates a charter by Geoffrey's reign in September, 1143 (ibid.).

page xx note 6 He uses his poverty and the necessity of his repairing the cathedral church and palace as excuses for not paying his personal respects to Pope Celestine on his election in 1143 (ep. no. 2).

page xx note 7 Among his contemporaries Arnulf is most frequently noticed by John of Salisbury, an acknowledged enemy, and one who says not a single kind word. On the other hand we have lavish tributes from such men as St. Bernard, Peter the Venerable and Peter of Blois. For a consideration of the conflicting views of modern French authors see de Formeville, Histoire, ii, 61Google Scholar, and Simon, G. A., Recherches … sur le séjour de S. Thomas Becket à Lisieux en 1170 (1926), p. 25Google Scholar. Among these the centre of the controversy has been whether or not Arnulf was sympathetic to Becket during his exile. This is an unfortunate point at which to assess the bishop's character, because passions which were aroused then are not yet dead. But for real lack of perspective one has to turn to English writers, where the interest in Arnulf has been almost entirely confined to the Becket episode, and where judgments appear to have become standardized. For them Arnulf is the intriguing bishop of Lisieux. A recent popular biography of Becket mentions Arnulf but once, and he appears as ‘an unscrupulous churchman’.

page xxi note 1 Epp. nos. 17, 65, 77–9; cf. 64, 80, 91, 104 and 113.

page xxi note 2 See his interesting remarks on the duties of a judge, below, p. 60.

page xxi note 3 Ep. no. 30.

page xxi note 4 He relates a ribald joke of Gerard, bishop of Angoulême, and exclaims, ‘O stupenda mentis obstinatio! o detestabilis impudentia linguae! o digna depositione responsio!’ (Invectiva, cap. 1).

page xxi note 5 John of Salisbury, Hist. Pont. (ed R. L. Poole), passim; cf. pp. 55–6, ‘ambo [bishops of Lisieux and Langres] facundi, ambo sumptuosi, ambo (ut creditur) discordie incentores et expertes timoris Domini; sed consiliosior et magnanimior Lingonensis … Nec erat inter eos qui magnanimitate prior haberetur’.

page xxi note 6 Consider the reception of his sermon at Tours (see below, p. xli).

page xxi note 7 See below, p. xxx.

page xxii note 1 See below, p. 169.

page xxii note 2 John of Salisbury: ‘mendosus ille et mendax’, Materials, v, 105Google Scholar; ‘Sedunum procul dubio scio, quia Lexoviensis, si venerit, nihil asserere verebitur; notus enim mihi est, et in talibus expertus sum fallacias ejus’, ibid., v, 101.

page xxii note 3 ‘[Arnulfus] gratia hospitalitatis munificentia celeberrimos famae titulos acquisivit’, Peter of Blois, ep. no. 91, M.P.L., ccvii, 239Google Scholar; cf. note 7, and see below, p. 210.

page xxii note 4 Cf. epp. nos. 51 and 52.

page xxii note 5 See below, p. 118.

page xxii note 6 Hugh, archbishop of Rouen, Praefatio ad Tractatum in Genesim, seu de sex dierum operibus, ‘Arnulpho Viro erudito Lexoviensi episcopo, filio suo carissimo, Hugo Rotomagensis sacerdos, spiritum sapientiae, lumen doctrinae’ (Bessin, G., Concilia Rotomagensis Provinciae (Rouen, 1717), ii, 28Google Scholar). This dedication is not mentioned in the H.L. Arnulf wrote an epitaph for Hugh (poem no. 16).

page xxii note 7 Cf. the remark of John of Salisbury, ‘Lexoviensis autem nitebatur de eloquencia et industria negociorum, de titulo liberalitatis et nugis curialibus, quas sub facetiarum colore uenustabat’ (Hist. Pont., p. 56).Google Scholar

page xxii note 8 Epp. nos. 11–13.

page xxii note 9 Ep. no. 26.

page xxii note 10 Below, p. 201.

page xxiii note 1 See Williams, John R., ‘William of the White Hands and Men of Letters’, in Anniversary essays in med. hist, presented to C. H. Haskins (Harvard, 1929).Google Scholar

page xxiii note 2 See below, p. 137.

page xxiii note 3 Ep. no. 27.

page xxiii note 4 Cf. ep. no. 31, which is a masterly effort of accumulated argument.

page xxiii note 5 Cf. the use of redhibitoria (p. 93), and the phrase in anathematis commisisse sententiam (pp. 89 and 162). Giles quietly altered commisisse to incurrisse. Arnulf provides almost the first example of the use of the word apostoli in the sense of letters of appeal (below, p. 23).

page xxiii note 6 Poem no. 14, and see Raby, F. J. E., History of Secular Latin Poetry in the Middle Ages (Oxford, 1934), ii 43Google Scholarseqq.

page xxiv note 1 Ep. no. 27.

page xxiv note 2 ‘vir admodum callidus, eloquens, litteratus’, Torigni, , p. 142.Google Scholar

‘Affuit Arnulfus antistes Lexoviensis Ingenii virtus eloquii nitor’.

(Stephen de Rouen, Draco Normannicus, in Chronicles of … Stephen, etc. (Rolls Series, 1885), ii, 715); see p. xxi note 5, and p. xxii note 7. For the reputation of ‘Lexoviens’, see John of Salisbury, ep. no. 60, M.P.L., cxcix, 43 seqq.

page xxiv note 3 See below, p. xli.

page xxiv note 4 Introduction to his sermons, p. 2.

page xxiv note 5 See below, p. xlvii, seqq.

page xxiv note 6 Simon, Recherches, quoting Ch. Vasseur, Notice Mstorique et archéologique sur la Maison-Dieu et les Mathurins de Lisieux (1861).Google Scholar

page xxiv note 7 See below, p. xlv.

page xxiv note 8 See below, p. lx.

page xxiv note 9 Below, p. 181.

page xxiv note 10 Pp. 56, 63, 112 and 181.

page xxv note 1 Below, p. 217.