Introduction

Painful oral mucosal lesions are frequently encountered in childhood.Reference Faden 1 - Reference Fleisher and Ludwig 3 Most of those affected have a self-limited viral infection,Reference Hopper, McCarthy and Tancharoen 4 and management is usually supportive. There is some limited evidence for the use of anti-viral agentsReference Amir, Harel and Smetana 5 , Reference Nasser, Fedorowicz and Khoshnevisan 6 ; however, this does not address children’s acute pain needs. As per current literature, the vast majority of children with acute gingivostomatitis are discharged home with advice regarding hydration, criteria for return to medical care, and pain management.Reference Faden 1 , 7 - Reference Mell 9 Analgesia is an essential component of therapy for gingivostomatitis with added benefits that go beyond short-term patient comfort. For example, studies suggest that patients seeking antibiotics may in fact simply want treatment for pain,Reference Chan, Russell and Robak 10 analgesic use has been associated with higher parental satisfaction,Reference Amir, Harel and Smetana 11 and properly treated oral pain can lead to increased fluid intake, and may decrease acute care visits or hospitalization. 12

Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are considered first-line analgesic agents for most mild-moderate pain. 13 Warm salt-water gargles, oral rinses, sprays, viscous lidocaine, and lozenges have been used as over-the-counter (OTC) alternatives, when these first-line agents are not adequate.Reference Hopper, McCarthy and Tancharoen 4 , Reference Hale and Wojnarowska 14 , Reference Wolfson, Hendey and Ling 15 Other options may include oral opioids or a combination of prescription and/or OTC medicines to form a mouthwash preparation.Reference Faden 1 , Reference Fleisher and Ludwig 3 , Reference Mell 9 Our study’s objective was to describe the current national practice pattern and attitudes of pediatric emergency physicians with respect to analgesic use in children with gingivostomatitis, in order to inform future randomized trials.

Methods

Study design, setting, and population

A descriptive cross-sectional survey was conducted from October 2013 to March 2014. Research ethics approval was obtained from the University of Alberta. This national survey was administered to all pediatric emergency physicians in the Pediatric Emergency Research Canada (PERC) database. At the time of this study, the PERC network included all 15 pediatric teaching hospitals across Canada, with a total of 204 physician members.

Survey protocol

This study followed recommended methodological guidelines for self-administered clinician surveys.Reference Burns, Duffett and Kho 16 Survey items were created through literature review and evaluated by an expert panel composed of five individuals, including pain researchers, pediatric emergency physicians, and survey methodology experts. Electronic surveys were distributed and managed by an arms-length data management group at the University of Alberta. Study data were collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tool, a secure, Web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.Reference Harris, Taylor and Thielke 17 Survey distribution followed a modified Dillman protocol.Reference Dillman 18 On day 0, a letter of introduction was emailed to eligible participants. On day 7, an electronic survey was emailed. On day 21, the e-survey was re-sent to non-respondents. Contact information for non-respondents was provided to a research assistant. On day 35, a final paper survey was posted to non-respondents. These paper surveys were devoid of identifying information and returned in self-addressed envelopes. Consent to participation in the study was implicit upon completion of the survey. Any and all questions could be skipped, at the respondent’s will. Survey data were presented to the study team in an anonymized, aggregate form.

Study measurements

A 25-item survey was designed following item generation, item reduction, pre-testing, pilot testing, and clinical sensibility testing.Reference Burns, Duffett and Kho 16 , Reference Mello and Merchant 19 We collected variables related to demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, years of experience), clinical behaviours (e.g., preferred analgesics, frequency of analgesic use), factors that may influence practice (perceived barriers and facilitators to analgesic use), and future directions for research.

Four clinical vignettes with varying patient age (10-month-old or 12-year-old) and severity (mild or severe) were used. One specific mouthwash (Akabutu’s) was included due to its familiarity to local investigators. Like many mouthwash recipes, Akabutu’s contains saline, hydrocortisone, nystatin, lidocaine, and glycerin.

Hypothesis

We hypothesized that the majority of physicians would recommend simple analgesics, such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen, as well as compounded formulations. Use of other medications were thought to be related to various clinician demographic characteristics.

Data analysis

Univariate summaries (means, weighted means, medians, standard deviations, ranges) were provided for continuous variables (e.g., age), and frequencies and percentages were used to summarize categorical variables (e.g., sex). Chi-square tests were used to test the significance of categorical variables. Multiple-response analysis was used wherever respondents were allowed to choose more than one response for a single question. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (Version 22) in consultation with the Biostatistics Consultant Group at University of Alberta.

Results

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents

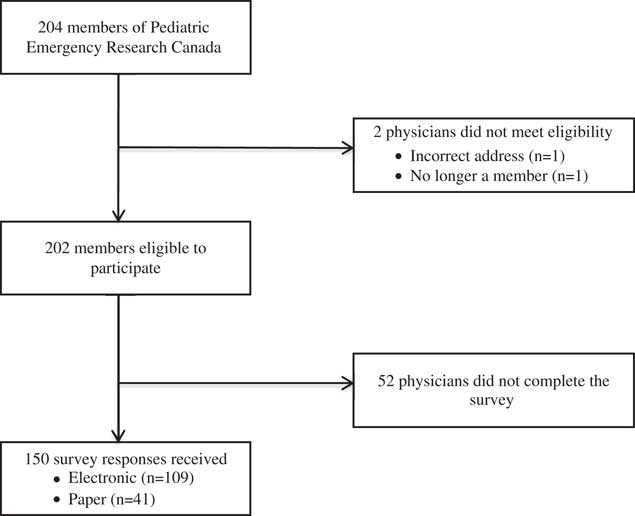

One hundred fifty physicians completed the survey, leading to a response rate of 74% (150/202) (Figure 1). Table 1 shows demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Figure 1 Flow diagram.

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of respondents (n=150, unless otherwise stated)

FRCPC = Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Canada; CCFP-EM = Canadian College of Family Physicians (Emergency Medicine); PEM = pediatric emergency medicine

* Pediatric hematology/oncology, DIP Sports Medicine.

Clinical behaviour

Physicians preferred to use both acetaminophen and ibuprofen concurrently (72%, 108/150) for the first-line treatment of pain related to acute gingivostomatitis, as compared to ibuprofen alone (19%, 29/150), acetaminophen alone (7%, 11/150), or neither agent (1%, 2/150) (p<0.0001). Further, this preference did not vary with the highest level of training (p=0.713), experience (<6 years, 6-10 years, >10 years) (p=0.193), or percentage of job spent in pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) (<25%, 26%-50%, 51%-75%, 76%-100%) (p=0.571). Among those who indicated they preferred to use ibuprofen and acetaminophen concurrently, 90% (83/99) chose ibuprofen when asked to pick their one preferred first-line agent.

Sixty-three percent (92/147, p=0.002) of respondents reported that they had not recommended any other OTC analgesia other than acetaminophen and/or ibuprofen for gingivostomatitis in the prior year. Just over 50% (73/144) of respondents indicated that they had provided compounded medicine (i.e., Akabutu’s mouthwash, Benadryl plus Maalox, Benadryl/Maalox/Lidocaine) for gingivostomatitis in the last year; 49% (67/138) reported that they had provided prescription analgesia (i.e., Naproxen, oral steroid, oral opioids). No physicians reported offering complementary and alternative therapies.

PEM-trained physicians and those working greater than 75% PEM used prescription analgesia more often than other physicians (p=0.044 and p=0.021, respectively). The amount of time spent working in PEM influenced the reported provision of compounded medicine, with those working greater than 75% being less likely to provide a compounded medicine (p=0.010).

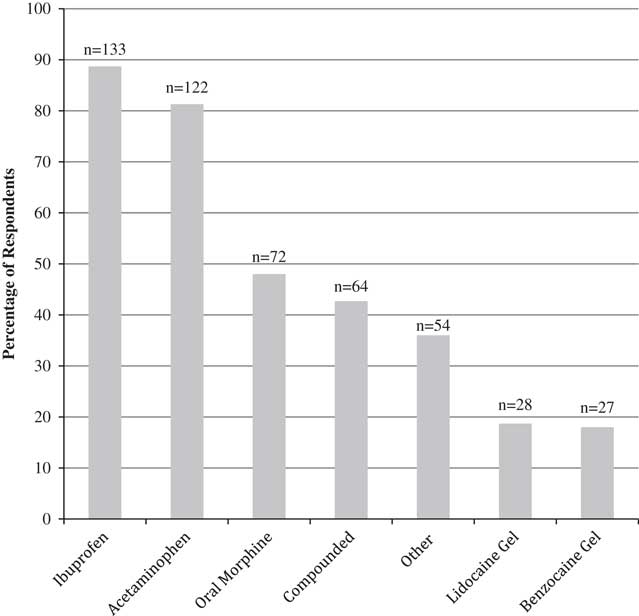

Figure 2 outlines the top five preferred analgesic recommendations for acute gingivostomatitis. Respondents with Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons (Canada) certification in pediatrics and those working less than 25% PEM preferred ibuprofen, acetaminophen, and oral morphine, but chose lidocaine more frequently than compounded preparations. The most commonly preferred (55%, 35/64) compounded analgesic agent was a Benadryl (diphenhydramine) plus Maalox (magnesium hydroxide/aluminum hydroxide/simethicone) combination. Other notable compounded formulas included Akabutu’s mouthwash (28%, 18/64), viscous lidocaine in Kool-Aid (6%, 4/64), “magic mouthwash” (5%, 3/64), lidocaine/antacid (3%, 2/64), Seattle mouthwash (2%, 1/64), and a locally compounded formulation (2%, 1/64).

Figure 2 Top five preferred analgesics for acute gingivostomatitis (n=150).

In the setting of mild gingivostomatitis, after appropriate dosing of acetaminophen and ibuprofen, the number one ranked treatment choice was “no further treatment” for both a 10-month-old infant (28%, 33/116) and a 12-year-old adolescent (26%, 29/113). Those who did treat further chose Benadryl plus Maalox as their number one ranked choice for both a 10-month-old (22%, 26/116) and a 12-year-old (21%, 24/113).

In the setting of severe gingivostomatitis, after appropriate dosing of acetaminophen and ibuprofen, the number one ranked treatment choice by responding physicians was oral morphine for both a 10-month-old infant (43%, 51/118) and a 12-year-old adolescent (44%, 52/118). Further, the majority of respondents (88%, 132/150) did not alter their practice on discharge. Among those who did, the most commonly cited advice was using cold foods as analgesia (24%, 4/17) and avoiding painful food/drink (29%, 5/17).

Factors that may influence practice

Table 2 depicts what respondents reported as influencing their choice of analgesia for acute gingivostomatitis. A significant proportion of respondents indicated that they did not know what the best evidence was for analgesia in acute gingivostomatitis (34%, 45/148) and those who knew the evidence (61%, 63/103) felt that it was either “very weak” or “somewhat weak.”

Table 2 Perceived barriers to optimal pain management of acute gingivostomatitis (n=84)

* Parental expectations and anxiety (3), difficulty assessing/quantifying pain (3), no narcotic prescription pad (2), patient age (2).

† Barriers not listed were each n=1.

The most commonly reported barrier to optimal pain management was the difficulty of administration of oral medication to children (15%, 13/84). Other barriers are described in Table 3.

Table 3 Factors affecting analgesic choice (n=147, unless otherwise stated)

Future directions

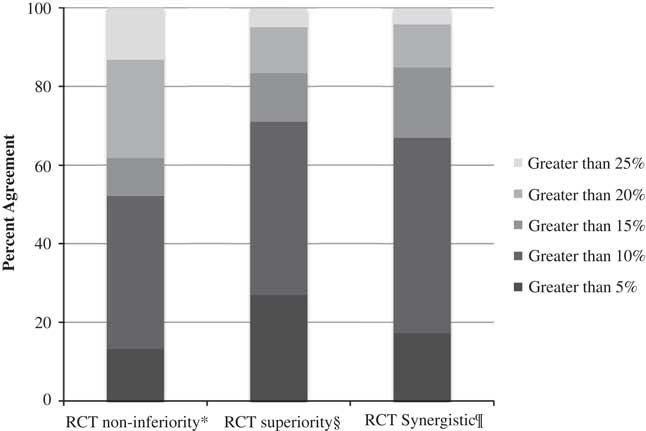

In order to help with the design of future trials, respondents were asked what percent difference between study drugs would be clinically significant. Figure 3 depicts the respondent agreement for a variety of trial designs.

Figure 3 Difference between a study drug and respondent’s first-line treatment deemed clinically significant. * non-inferior in efficacy, difference in palatability and ease of administration, n=144. § superior in efficacy, same cost, ease of administration, and side effects, n=145. ¶ synergistic in efficacy, n=145.

Discussion

Despite a paucity of direct evidence for use in acute gingivostomatitis, a majority of respondents indicated that they used ibuprofen and acetaminophen concurrently as a first-line treatment. To date, there is limited but promising evidence to support the practice of combining acetaminophen and ibuprofen for pain treatment in children.Reference Smith and Goldman 20 - Reference Ong, Seymour and Lirk 24 As noted by others, there remains a need for large-scale studies on both the efficacy and safety of this combination for the treatment of pain.Reference Smith and Goldman 20

When asked to choose their preferred oral analgesic, respondents showed a strong preference for ibuprofen over acetaminophen. Despite the likely benefit of ibuprofen’s anti-inflammatory effect, there is no direct comparison of ibuprofen and acetaminophen’s analgesic efficacy in acute gingivostomatitis. Still, there is mounting evidence that ibuprofen has equal or better analgesic properties for a variety of other indications in children.Reference Pierce and Voss 25 , Reference Clark, Plint and Correll 26 As such, ibuprofen may be the best first choice for simple oral analgesia in the treatment of acute gingivostomatitis, but direct evidence is lacking.

Almost half of our survey respondents selected oral morphine as one of their top five analgesic preferences, second to only acetaminophen and ibuprofen overall. This is likely a reflection of a physician’s desire to identify a suitable alternative to codeine (which has been removed from virtually all Canadian pediatric hospital formularies) combined with fears regarding oxycodone addiction potential. 27 Currently, there is no evidence to suggest that any one agent is the better opioid for children, highlighting a need for a well-designed, large, multi-centre trial of oral opioids for acute pediatric pain.

When presented with the vignette of a patient with severe gingivostomatitis (with inadequate response to combination acetaminophen and ibuprofen), respondents ranked oral morphine as their number one choice regardless of patient age. This suggests that the majority of respondents were comfortable providing opioids to both small children and adolescents. This is in contrast to previous studies that have shown that decreasing age was correlated with a decrease in reported treatment with opioids.Reference Kircher, Ali and Drendel 28 The majority of our respondents had subspecialty training in PEM or specialty training in pediatrics, and it is possible that more experience with the treatment of children may have led to this greater reported comfort.

Half of respondents indicated that they had prescribed/provided compounded analgesia within the previous year. Some of these preparations were originally designed for treatment of patients with oral mucositis related to cancer (e.g., Akabutu’s mouthwash). Given the dissimilarities in pathophysiology, acute gingivostomatitis will likely be imperfectly treated with an agent intended for cancer-related mucositis. Among the reported compounded medicines in our study, the most pharmacologically intuitive ingredients to include in a topical compounded agent would include diphenhydramine or lidocaine, for their known analgesic properties.Reference Pavlidakey, Brodell and Helms 29 Such compounded formulas can vary in viscosity, flavour, and volume of administration. The unique properties of each preparation could have a significant impact on palatability, ease of administration, and clinical effectiveness.

To our knowledge, only two randomized controlled trials have been conducted in the treatment of gingivostomatitis.Reference Hopper, McCarthy and Tancharoen 4 , Reference Amir, Harel and Smetana 5 Hopper et al. compared 2% lidocaine to placebo in improving oral intake in children with painful infectious mouth ulcers. No difference was found in fluid intake or the need for rescue medication.Reference Hopper, McCarthy and Tancharoen 4 Amir et al. compared oral acyclovir to placebo in herpetic gingivostomatitis and found that, when started within the first 72 hours, acyclovir shortened the duration of feeding and drinking difficulties.Reference Amir, Harel and Smetana 5 This study did not address other causes of gingivostomatitis. Given the limited number of studies, it remains unclear which option is the optimal choice.

More than half of the physicians surveyed reported at least one barrier to optimal pain management. The most commonly cited barrier was difficulty in administration of topical or oral analgesia to children. Other respondents mentioned lack of effective options and side effects. This suggests that, after clinical effectiveness, important secondary outcomes to consider in future studies would include side effects and ease of administration. Some respondents also disclosed that concern about opioid use, either from the family or the practitioner themselves, was a major barrier to adequate analgesia. This reinforces the need for ongoing education around the safety and efficacy of opioids in children, when used in accordance with the best practice. Finally, a number of respondents listed lack of availability of a desired medication as a barrier to optimal pain management. For example, one popular demulcent agent in many topical preparations (Maalox) has been unavailable in Canada since 2012.

Limitations

It is possible that some survey respondents were affected by social desirability bias. We attempted to mitigate this bias by providing the survey to participants through an anonymous self-administration platform, and through the use of neutral question style.

No comparison can be made between respondents and non-respondents. Because of this, we cannot be certain that our results were not affected by self-selection. However, this is likely mitigated by our high response rate.

Only 50% of physicians working in emergency departments in pediatric hospitals are members of PERC. Also, many children are treated in non-pediatric emergency hospitals across Canada. The treatment of gingivostomatitis by these community providers and other pediatric emergency physicians may differ from the behaviours reported in our survey.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this national study is the first to detail analgesic use by pediatric emergency physicians for patients with pain-related to acute gingivostomatitis. As expected, the majority of physicians preferred simple analgesics, such as ibuprofen and acetaminophen, and most frequently used them in combination. The most commonly reported second-line analgesic agents were oral morphine and compounded agents, but practitioners also frequently cited a variety of other agents. The breadth of reported analgesic agents in use demonstrated by this survey highlights the lack of best evidence for the treatment of pain for this condition. This study has provided some direction as to which medications to consider for a trial study, namely oral morphine and a combination of diphenhydramine and antacid suspension. Future studies will also need to carefully consider the many barriers to optimal pain management cited in this study.

Acknowledgements

Drs. Amy Drendel, Hsing Jou, Shawn Dowling, Antonia Stang, and Manu Kundra participated as members of an expert panel who helped with survey tool creation. Drs. Dominic Allain and Vince Grant participated in language editing/translation. Ms. Nadia Dow functioned as the research coordinator for this study. Ms. Melissa Gutland provided administrative support for the implementation of this study. Mr. Sung Hyun Kang assisted with statistical analyses. Dr. Joe MacLellan secured a grant from Women and Children’s Health Research Institute to support this work.

Competing interests: None declared.