No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

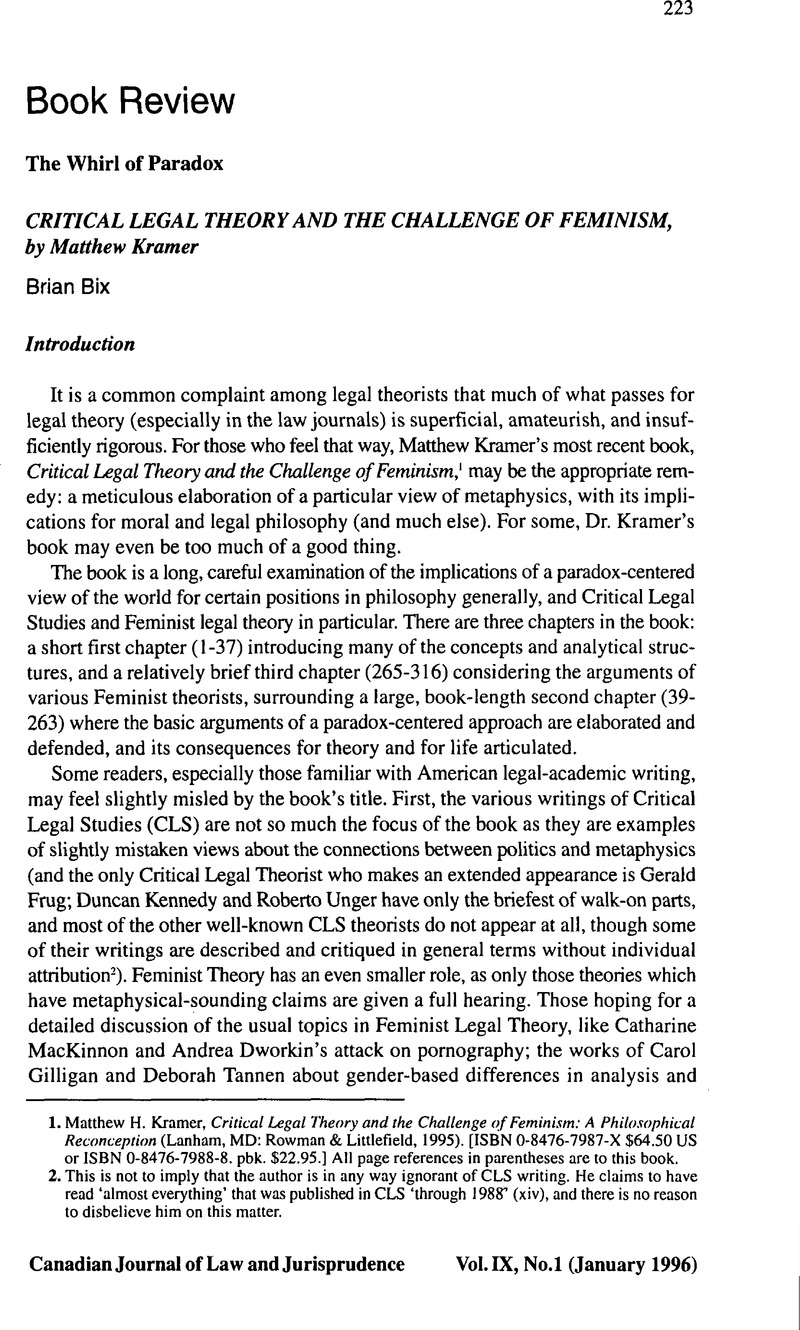

CRITICAL LEGAL THEORY AND THE CHALLENGE OF FEMINISM, by Matthew Kramer

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 June 2015

Abstract

- Type

- Book Review

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence 1996

References

1. Kramer, Kramer, Critical Legal Theory and the Challenge of Feminism: A Philosophical Reconception (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1995).Google Scholar [ISBN 0-8476-7987-X $64.50 US or ISBN 0-8476-7988-8. pbk. $22.95.] All page references in parentheses are to this book.

2. This is not to imply that the author is in any way ignorant of CLS writing. He claims to have read ‘almost everything’ that was published in CLS ‘through 1988’ (xiv), and there is no reason to disbelieve him on this matter.

3. Kramer describes the role of critical legal scholarship and feminist theory for him as having been more that of ‘broad inspiration rather than … extensive guidance’(xv).

4. However, the same would be true if one were trying to show the absence of a division, and, according to the author, one can beg the question in more or less persuasive ways. (138)

5. In the book’s ‘Preface’, Kramer presents the metaphysics/politics and metaphysics/mundaneness distinctions as having profound implications for ‘religious outlooks’, in that they ‘impeach all attempts to fuse the descriptive and prescriptive’ and they ‘forestall the derivation of concrete circumstances from any ultimate principles’(vii).

6. Kramer does not himself adopt neo-pragmatism, at least not in its pure form. He is more sympathetic to a ‘ transfigured and duly paradox-focused version of neopragmatism’(151).

7. E.g., Nozick, Robert, Philosophical Explanations (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 1981) at 8.Google Scholar

8. While 1 discuss the two types of paradoxes separately, the book treats paradoxes of infinity as a sub-class of the paradoxes of individuation. (64)

9. Here (71), Kramer draws upon Wittgenstein’s rule-following considerations for support; and they are brought in later in the argument as well. (89–90) Arguably, Wittgenstein’s approach to philosophy, and his discussion of rule-following, are incompatible with a paradox-highlighting approach, but this is an issue that goes beyond the scope of the present review.

10. The author does concede that a paradox-centered approach may seem at the least ‘overrefined’ or lacking efficacy, when applied to mundane topics. (78–80)

11. In particular in a short piece, ‘Deconstruction’, to be published in The Philosophy of Law: An Encyclopedia (forthcoming, Gray, C., ed., Garland Publishing).Google Scholar

12. Kramer states that he avoids the term ‘Deconstruction’ in the book because the tag has become so widely misunderstood and misused, (xi) He also states that Critical Legal Theory and the Challenge of Feminism, to some extent, goes beyond what the main proponents of Deconstruction have argued.

13. Kramer, ‘Deconstruction’, supra note 1 I.

14. Ibid.

15. Frug, Gerald, ‘The Ideology of Bureaucracy in American Law‘ (1984) 97 Harv. L. Rev. at 1276.CrossRefGoogle Scholar While Kramer offers a number of criticisms of this article in the book (54-59, 197-98, 282), he also refers to the Frug article as ‘a most important essay from the critical legal studies movement’ (197).

16. An example, and by no means the most extreme one available: ‘the metaphysical/mundane breach cannot but develop as a to-and-fro of incoherently self-deranging options that tumble into being what they can never be, in order to remain what they are’ (128).