Introduction

Police use of lethal force has attracted criticism for several years. For example, in 2013, a member of the Toronto police used a semi-automatic Glock handgun to shoot Sammy Yatim eight times on an empty streetcar. Onlookers recorded the incident which sparked furious complaints about the deadly use of firearms.Footnote 1 Yatim’s death raises several issues, including the effect of systemic racism on the use of force, and the main topic of this article: when and why police forces replaced traditional service revolvers with semi-automatic handguns that could quickly discharge considerable quantities of ammunition.

In offering the first scholarly analysis of the shift from revolvers to semi-automatic handguns in Canada, this article draws from, and contributes to, literature on police militarization, paying close attention to the role of firearms marketing in shaping police gun culture. Scholars note that police militarization can occur along several dimensions, including a “material dimension,” which encompasses the adoption of weapons and equipment to more effectively use violence. This dimension involves outfitting special weapons and assault teams (SWAT), also known as “tactical teams” or “emergency response units.”Footnote 2 Scott W. Phillips notes, however, that there is a “distinct absence of scholarship examining the history of weapons used in policing,” despite “how important guns are in police culture, their impact when used and the amount of scholarship dedicated to examining their use.”Footnote 3 Police militarization scholars often note the adoption of assault rifles by police, but pay less attention to changes in handguns. Canada’s leading historian of the police, Greg Marquis, has considered how the 2017 shooting in Moncton that left three Mounties dead led to plans to provide front-line members with assault rifles, though he has not examined the transition from revolvers to semi-automatic handguns in detail.Footnote 4 Brenden Roziere and Kevin Walby believe it is “time to begin examining police militarization in Canada,”Footnote 5 and, as we show, part of this is how front-line police were rearmed in the 1990s.

Until the early 1990s, most Canadian police carried revolvers, as they had for decades. These weapons were deadly but generally carried just six rounds of ammunition and were slow to reload. In the 1990s, most police exchanged their traditional service revolvers for modern semi-automatic handguns. Several factors contributed to this transition. Relatively rare, but high-profile, shootings of police motivated the change. Law enforcement commemorated officer deaths to show the dangers of their work, the bravery of officers, and the need for new guns to protect them from allegedly better armed criminals. The firearms industry encouraged the rearming of police through an aggressive marketing campaign emphasizing that modern police forces required more capable and advanced weapons and by highlighting the military lineage of their products. The transition to semi-automatic handguns sometimes proved controversial, as human rights advocates believed the new handguns could result in excessive use of force. Despite this concern, most police were rearmed by the beginning of the twenty-first century.

A key primary source for this article is Blue Line magazine, which has been carefully examined from 1989 to 2000. Blue Line declares itself “Canada’s national law enforcement magazine”Footnote 6 and is popular with front-line officers. It was first published in 1989 as the brainchild of publisher / editor / writer Morley Lymburner, a veteran of the Metropolitan Toronto Police Force. He said that Blue Line had no political affiliation and that its purpose was to help keep police up to date. Lymburner remained the editor-in-chief of Blue Line until 2000.Footnote 7 The magazine includes articles on police training, equipment, policy, and weapons, as well as editorials and letters from readers. Blue Line also publishes numerous firearms industry advertisements marketing guns to police. The magazine thus offers an exceptional window into police debates about firearms and how the gun industry sought to cater to, and shape, the procurement of weapons. In addition to Blue Line, we draw information from other police publications, government documents, legislative debates, and newspaper coverage.

This article begins with a brief overview of the use of revolvers by police up to the 1980s. The efforts of the firearms industry to market semi-automatic handguns to police is then considered. Next, the article explores the debate over the possible transition from revolvers to semi-automatic pistols. Finally, we trace the adoption of semi-automatic handguns. The fractured nature of policing in Canada—with the existence of municipal, provincial, and federal services—means that broad claims about policing equipment must be stated with caveats, but our research demonstrates a remarkably rapid transition to semi-automatic handguns.

Revolvers and Their Adoption by Police

Handguns have undergone a technological transformation since the early nineteenth century. In the early 1800s, most handguns were muzzle-loaded weapons that held one round of ammunition. Samuel Colt famously produced a pistol designed with a revolving cylinder that held multiple rounds of ammunition, which became the basic design for other “revolvers,” with several companies producing such guns by the 1860s. Additional technological innovations improved the rate of fire of revolvers and increased the speed with which such guns could be reloaded. Early revolvers generally used a “single-action” mechanism, meaning that the user of the firearm had to manually pull back the hammer of the revolver. This cocked the hammer so that pressing the trigger made the hammer strike the primer of the ammunition. Cocking also rotated the cylinder of the revolver so that a new round was moved into position to fire. By the late nineteenth century, “double-action” revolvers became widely available (see Figure 1). Revolvers with this action automatically rotated the cylinder, cocked the hammer, and fired by just pulling the trigger. Revolvers were limited in their potential lethality by the number of rounds that their cylinders could hold (often between five and seven). Revolvers tended to be slow to load. Initial designs required the user of the firearm to remove the spent shell casings from each chamber in the revolver’s cylinder and then manually and individually insert new ammunition into each chamber. Gun manufacturers looked for ways to increase the speed with which such guns could be reloaded. Some developed revolvers that had hinges allowing for users to expose the chambers of the cylinder and thus more quickly reload (so-called “top-break” revolvers). Other manufacturers employed swing-out cylinders with “extractors” allowing all shell casings to be removed more quickly.Footnote 8

Figure 1. British Bull Dog Revolver (c. 1889), a “double-action” revolver. Source: Stark’s Catalogue, Charles Stark Co. (Toronto, c.1889), 237.

Many police in Canada began to carry revolvers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Early members of the Northwest Mounted Police were issued revolvers and rifles. In Hamilton, the death of a constable in 1884 led to the temporary provision of revolvers to constables on night patrol. Another constable’s death in 1904 contributed to the decision to arm Hamilton police with revolvers.Footnote 9 Some forces, however, waited to receive service revolvers. The fact that police in England generally did not carry firearms may have contributed to a reluctance to arm some Canadian police. Halifax police, for example, were finally armed with revolvers as standard equipment only in the early 1970s.Footnote 10 The Royal Newfoundland Constabulary had to wait even longer—its members started to carry service revolvers in the late 1990s.Footnote 11 By the mid-twentieth century, the standard revolver carried by police was a .38 calibre handgun that held six rounds of ammunition.Footnote 12

Marketing of Semi-Automatic Handguns to Police

In the 1990s, many Canadian police forces stopped using revolvers as sidearms and instead received semi-automatic pistols. In general, semi-automatic handguns carried more ammunition and were faster to reload. Unlike revolvers, which contained ammunition in cylinders, semi-automatic handguns usually held ammunition—typically at least twice as much as a revolver—in a magazine inserted into the handle of the weapon.Footnote 13 An operator could discharge all the ammunition in the magazine, then quickly remove the empty magazine and replace it with a full one. Depressing the trigger of a semi-automatic handgun both fired the weapon and loaded a new round into the gun’s chamber.

The firearms industry targeted police as an important market for semi-automatic handguns. Pamela Haag argues in The Gunning of America: Business and the Making of American Gun Culture that fewer and fewer Americans needed firearms as tools by the late nineteenth century. As a result, the gun industry worked ceaselessly to create and expand markets for its products, such as when it spurred interest in recreational hunting among urban, middle-class men and marketed revolvers as self-defence weapons.Footnote 14 The firearms industry also targeted the police market. In the late 1880s, the Charles Stark company, which billed itself as Canada’s biggest firearms retailer, advertised revolvers to police.Footnote 15 In the crowded gun market of the late twentieth century, the firearms industry continued its effort to create and expand markets for weapons. One aspect of this involved convincing police that their revolvers should be replaced with tens of thousands of semi-automatic handguns. Previously, such weapons had largely been used by, and associated with, the military. As Peter Squires notes, gun companies saw the police market as important, in part because selling semi-automatic handguns to law enforcement would make such guns more acceptable and alluring in the civilian market.Footnote 16

The gun industry’s intense marketing effort to get police revolvers replaced with semi-automatic handguns can be seen in the advertisements in Blue Line magazine. The first advertisement for a semi-automatic handgun in Blue Line appeared in a 1991 issue, and by 1995 several major gun companies—Glock, Smith & Wesson, Beretta, Ruger, and SIG Sauer—had bought advertisements.Footnote 17 Glock was the new kid on the block. This Austrian company produced polymer-framed semi-automatic pistols. The Austrian military began using the company’s guns in the 1980s, and Paul Barrett suggests that Glock aggressively marketed its modern handguns to police in part because it believed that police adoption would normalize these firearms in the minds of civilians, thus opening up the massive consumer market.Footnote 18 Smith & Wesson was an American company that had manufactured revolvers since the mid-nineteenth century. It had a long history of producing .38 calibre revolvers for police, but also manufactured semi-automatic handguns. Beretta, an Italian gun maker with roots that reached back to the sixteenth century, produced well-known semi-automatic handguns among its suite of firearm products. In 1985, Beretta won the contract to provide the primary sidearm to the American military, the Beretta 92FS (known in the American military as the M9). SIG Sauer, a Swiss company, began to produce semi-automatic handguns in the 1970s. Ruger (technically Sturm, Ruger & Company, Inc.) was an American company based in Connecticut that made a variety of weapons, including semi-automatic handguns.Footnote 19

In their advertisements, companies tended to include pictures of their firearms and assert the advantageous characteristics of semi-automatic handguns for police, while also articulating how the designs of their weapons differentiated their products from competitors. Businesses frequently described their firearms as more technologically advanced than revolvers and, in doing so, suggested that they would improve officer safety. Gun companies routinely pointed out that semi-automatic handguns carried more ammunition than revolvers. In a 1993 advertisement, Beretta pictured its handgun along with two magazines. One was a revolver cylinder holding six rounds of ammunition; the other was a Beretta magazine with fifteen rounds of ammunition (plus one round sitting separately for the gun’s chamber). Beretta said its gun had everything “you like about a revolver … and more,” referring to the ammunition, and claimed that the large number of rounds held by its semi-automatic pistol was a “life saving advantage.”Footnote 20 Many manufacturers portrayed semi-automatic handguns as having advanced ergonomic designs, allowing the guns to be pointed quickly and accurately, as if the weapons were extensions of shooters’ arms. For example, Smith & Wesson described the ergonomics of its Sigma semi-automatic handgun as ensuring that police could aim accurately. “Pick up any pistol, close your eyes, and point. Now open your eyes. If you’re pointing a Sigma, your aim will be straight.” “Aiming a Sigma is as natural as pointing your finger,” trumpeted Smith & Wesson, for the “Sigma’s superior pointability is the result of sophisticated research into how the human hand, wrist, and arm operate while grasping and firing a pistol.”Footnote 21

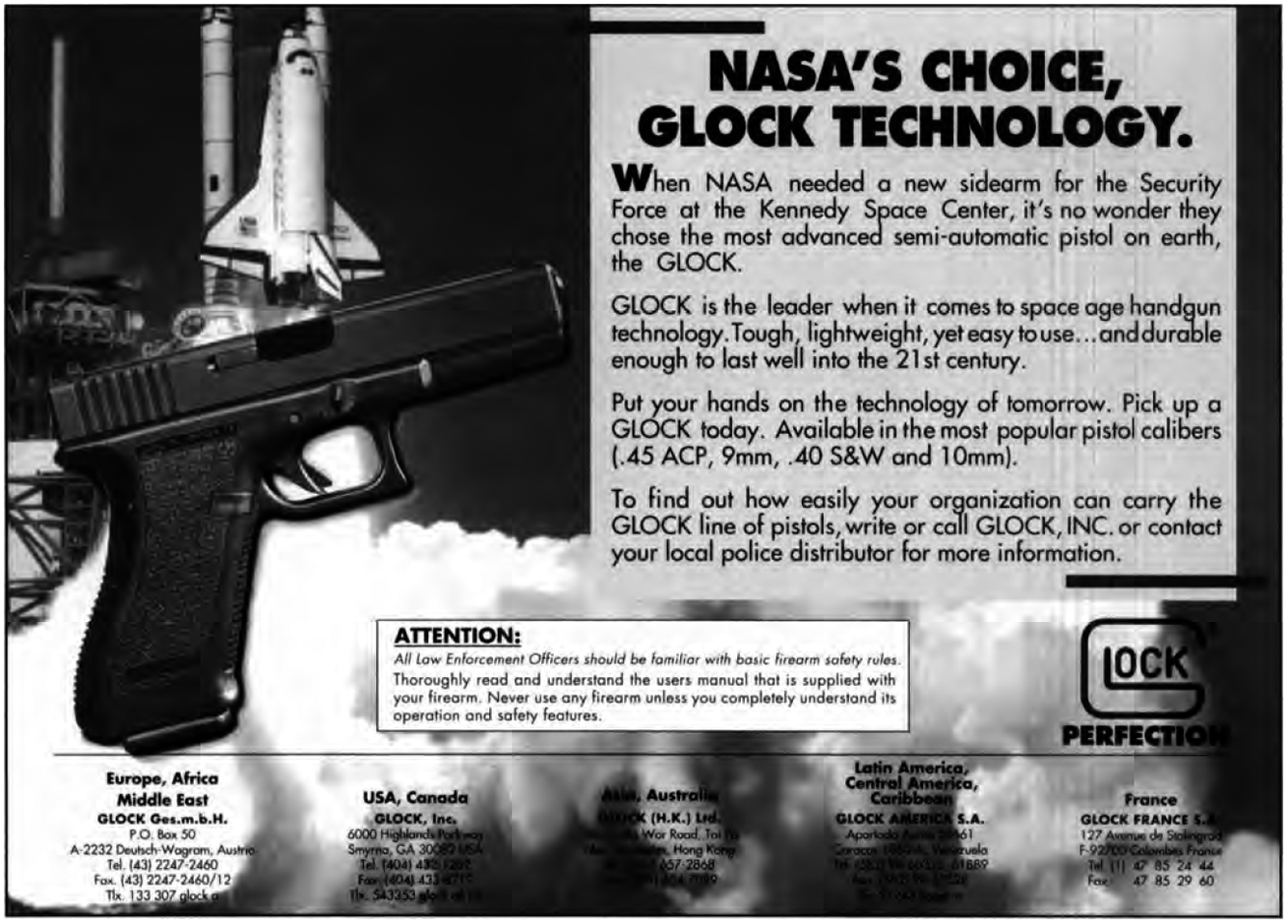

Glock strongly emphasized new technology, particularly its use of polymers. In 1992 it said that, while “other companies were improving upon their technology of the past,” Glock was “busy perfecting the technology needed for the 21st Century.”Footnote 22 In another advertisement, Glock superimposed a picture of its handgun on a NASA space shuttle, claiming that, “When NASA needed a new sidearm for the Security Force at the Kennedy Space Center, it’s no wonder they chose the most advanced semi-automatic pistol on earth, the GLOCK.” Glock was the leader “when it [came] to space age handgun technology.” It encouraged purchasers to put their “hands on the technology of tomorrow”Footnote 23 (see Figure 2). The message was clear: Glock was the technological leader, and police organizations should buy the most advanced weapon to be considered a “modern” force. Glock also claimed that the use of polymers and other materials made its handgun more durable than competitors’ products. For example, in 1993, Glock ran a full-page advertisement in Blue Line with ten bullet holes in the centre of the image. Glock described its gun as “Virtually indestructible,” in part because it was made with “tough polymer that can’t break down or corrode.” Glock bragged that the company froze one of its handguns in a block of ice, then submerged it in saltwater for fifty hours. “Then we used it to make this ad,” meaning, to make the bullet holes in the advertisement. In other words, police under threat could rely on the Glock to shoot.Footnote 24

Figure 2. Glock strongly emphasized new technology in its marketing. In this 1993 advertisement, it trumpets its association with the Kennedy Space Center to portray its semi-automatic handgun as advanced. Source: Blue Line, June–July 1993, 19. Reproduced with the permission of Blue Line.

Gun companies also used emotional appeals in their marketing to tap into the personal views of police and to possibly shape the broader attitude of law enforcement towards firearms. Police, like other groups of firearm users, tended to share a particular “gun culture.” As scholars have noted, gun cultures are not monolithic attitudes shared by citizens of an entire nation. Rather, there often exist distinct gun cultures affected by factors such as region, gender, or employment.Footnote 25 Many police shared attitudes to firearms, seeing them as symbols of authority and practical instruments needed to provide protection for themselves and the public. Gun companies thus often stressed how guns would make police “feel” when they possessed modern semi-automatic handguns. Police holding semi-automatic weapons would sense the robust construction of the handguns and imagine themselves as safe and authoritative. For example, in 1994, Beretta said that police carrying semi-automatic handguns “routinely express a feeling of greater confidence in being able to control dangerous situations.”Footnote 26

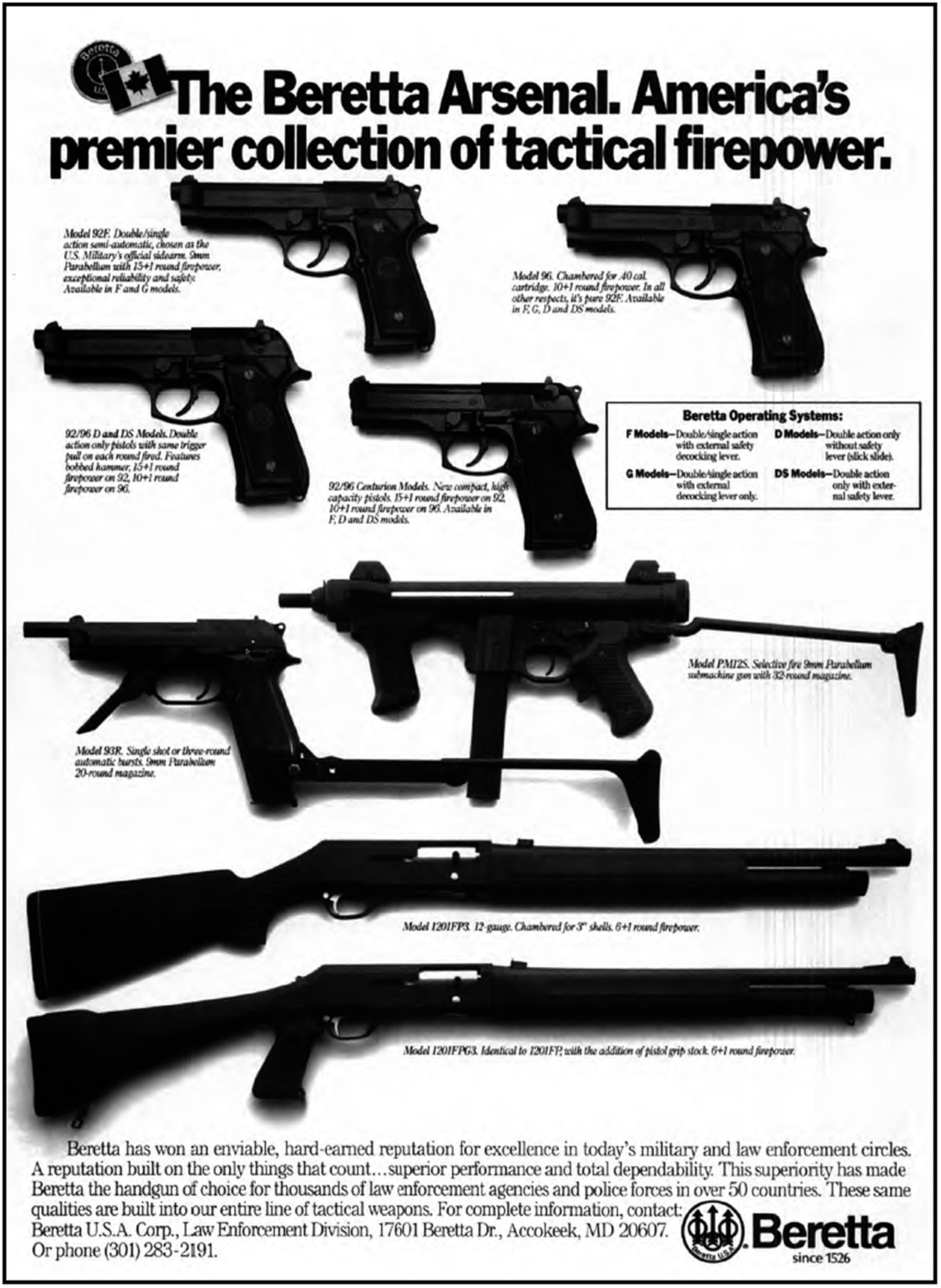

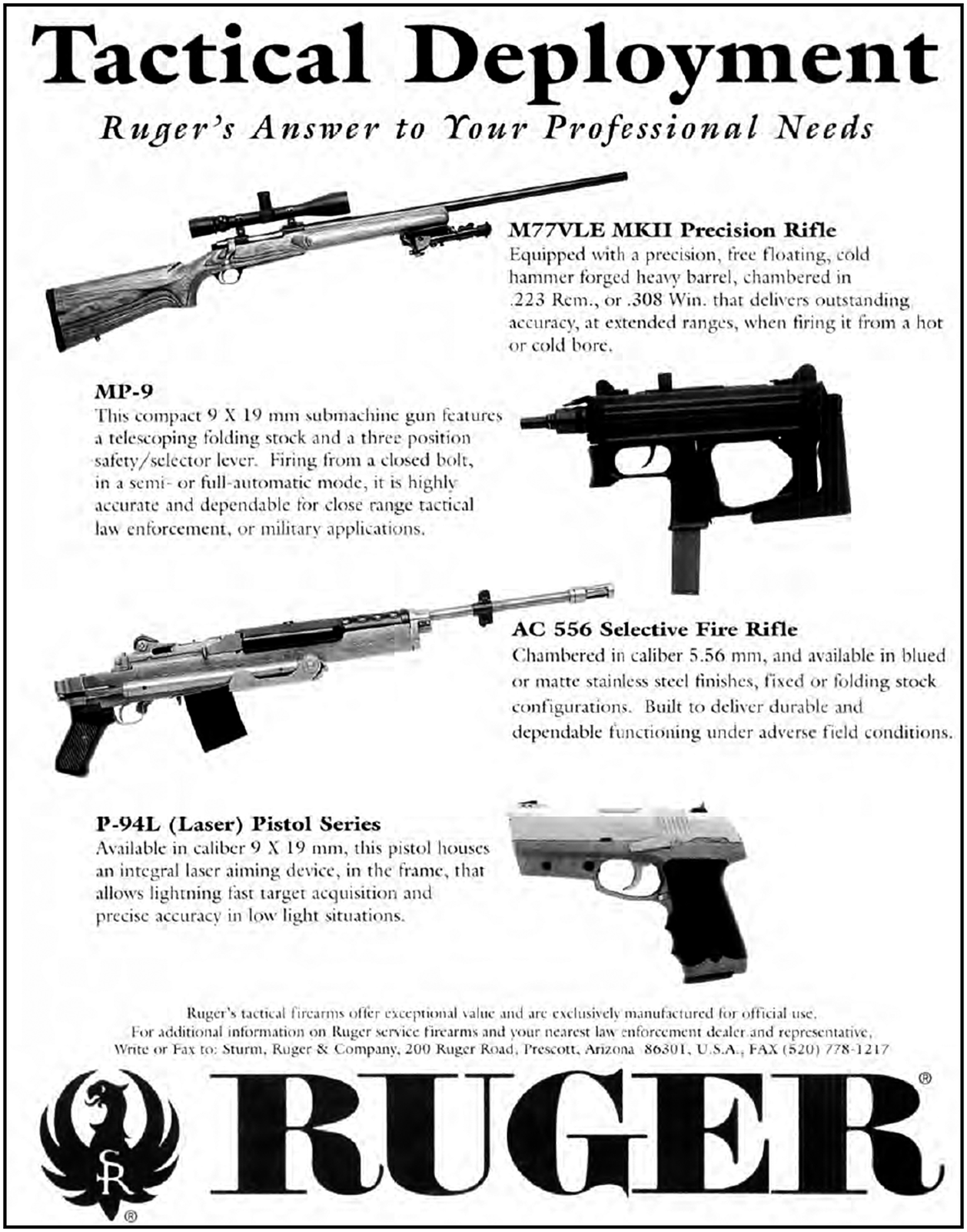

Firearm companies often noted the use of their semi-automatic handguns by the military, thus blurring the line between weapons appropriate for police and soldiers. As Squires notes, an association with the military “added enormously to a firearm’s reputation, its ‘aura’ and mystique.”Footnote 27 Beretta often diminished the distinction between weapons of war and weapons for policing. The company emphasized its success at securing a contract with the United States armed forces. In 1992 it used an advertisement that displayed the inner workings of the handgun it sold to the American military, using evidence of its procurement as proof of the gun’s quality.Footnote 28 In the May 1993 issue of Blue Line, Beretta began to publish full-page advertisements to market its new Model 96. It emphasized the gun’s “legendary reliability,” ergonomic design, easy maintenance, and safety features, as well as the fact that its handgun was the “standard handgun for the U.S. Armed Forces and over one thousand police departments.”Footnote 29 Beretta also mentioned the “Combat Style Frame” of one of its handgun models.Footnote 30 Beretta frequently employed the word “tactical” in describing its guns for police, which suggested military uses.Footnote 31 In 1994, Beretta used an advertisement showing a collection of semi-automatic handguns, shotguns, and an assault weapon, and said it offered “America’s premier collection of tactical firepower” (see Figure 3). Beretta claimed it had won “an enviable, hard-earned reputation for excellence in today’s military and law enforcement circles.”Footnote 32 Other gun makers also leaned into military connections. Ruger claimed that its handguns were built to meet NATO standards and employed the term “tactical”Footnote 33 (see Figure 4). SIG Sauer, meanwhile, noted that the American army had selected one of its semi-automatic handguns for use with some units.Footnote 34

Figure 3. Beretta trumpeted semi-automatic handguns as part of its suite of “tactical” firearms available to police. Source: Blue Line, February 1994, 7. Reproduced with the permission of Blue Line.

Figure 4. Like Beretta, Ruger offered a range of weapons to police, including semi-automatic handguns, sniper rifles, and fully automatic rifles, as “tactical” weapons. Source: Blue Line, June–July 1995, 27. Reproduced with the permission of Blue Line.

Revolvers vs. Semi-Automatic Handguns

Authors in Blue Line debated the relative merits of revolvers and semi-automatic pistols as police weapons, though the journal’s contributors eventually came to a consensus that police should possess semi-automatic handguns. Blue Line published its first article on this topic in 1991. Steven Sheppard threw cold water on the idea that police needed semi-automatic handguns, concluding that these weapons were not, in fact, better than revolvers. Sheppard was a staff sergeant with two decades of experience with the Metropolitan Toronto Police. He discussed the advantages and disadvantages of both kinds of firearms. He noted a few weaknesses of revolvers, such as limited ammunition capacity, but listed numerous disadvantages of semi-automatic pistols, including that police involved in shooting situations “may tend to fire more rounds trying to overcome lack of proficiency by using ‘firepower’ resulting in the term ‘spray and pray.’”Footnote 35 He also claimed that semi-automatic pistols often had more recoil than .38 calibre revolvers, were more difficult to operate, and could not be handled easily by small or weak-wristed officers.

Sheppard’s article downplaying the advantages of semi-automatic pistols precipitated several harsh responses in Blue Line. W. N. Burton wrote that he had “never seen such a biased and slanted list of advantages and disadvantages associated to the pistol.”Footnote 36 Burton noted that many American police services had switched to, or were considering the switch to, semi-automatic handguns, and that some Canadian emergency response teams had also acquired such firearms. Burton argued that, if police officers could be expected to modernize by mastering new computer technology, then those same police could also learn how to handle and fire semi-automatic handguns. In a letter to Blue Line, RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) member Brian Largy was even harsher in his assessment of Sheppard’s article: “If one didn’t know better, it would appear that Mr. Sheppard had been commissioned by some police administrative department to dissuade the average police officer, who is not overly familiar with firearms, from requesting or demanding a switch from revolver to semiautomatic pistol.”Footnote 37

The question of how police should be armed became entwined with concerns of excessive use of police force, particularly against minorities. Several high-profile shootings of Black civilians in Toronto in the late 1980s sparked community protest and brought the topic of police racism to the attention of the public. The Ontario government responded by creating the Task Force on Race Relations and Policing.Footnote 38 The task force’s report, released in 1989, made several recommendations regarding police use of force, including amendments to the Ontario police act specifying that firearms only be fired in defence of life and that reports be filed by police officers following the use of force. Notably, the report’s recommendation that police shootings be investigated by an independent civilian organization, a request often made by community groups such as the Black Action Defence Committee, led to the creation of the Special Investigations Unit (SIU). The SIU was designed as an independent body tasked with investigating possible wrongdoing of police in incidents in which a person died or was seriously injured.Footnote 39

Police violence continued to be a controversial public topic into the early 1990s, encouraged by shooting deaths, such as the police killing of Raymond Lawrence by Peel Regional Police in 1992, just days after a jury acquitted four police officers charged with beating Rodney King in Los Angeles the previous year.Footnote 40 The provincial NDP (New Democratic Party) government, under Premier Bob Rae, announced it would introduce reforms to require police officers to complete a report whenever they drew or discharged guns, rather than, as before, when they fired weapons. The plan to strengthen reporting requirements incensed some police, who said it would lead to unnecessary paperwork, make police reluctant to draw weapons in dangerous situations, and create a paper trail that could be used to later malign as “trigger happy” officers who fired their handguns.Footnote 41 Doug Ramsey of the Metropolitan Toronto Police Association said the new reporting requirement was “just another attack on the credibility of the police.”Footnote 42 There tended to be political overtones to the police push back. Representatives of both the Police Association of Ontario and the Metro Toronto Police Association specifically criticized the advocacy of the Black Action Defence Committee, referring to the group as “notoriously anti-police.”Footnote 43 Articles in Blue Line hinted at distrust of the NDP government, with authors arguing that the Rae government was soft on crime and failed to appreciate the dangers faced by front-line police.Footnote 44 The subsequent decision of the NDP government to appoint a commission to examine the problem of systemic racism in the province’s criminal justice system accentuated these complaints. Toronto human rights lawyer Peter Rosenthal told the commission that providing semi-automatic handguns to police could result in more civilian deaths. Instead, he wanted police to be more creative in how they approached tense situations.Footnote 45 Rosenthal’s comments produced a furious response from police, including the chief of the London Police Force, Julian Fantino.Footnote 46 The part of the commission’s final report that examined shootings by police focused on how such incidents were subsequently reported and investigated.

Authors in Blue Line emphasized the dangers faced by police from well-armed criminals and eventually argued the necessity of semi-automatic handguns to keep officers safe. In its first issue, Blue Line reported that police died “in bars, stores and homes, on sidewalks and highways, in alleys and gutters, predominantly by guns.”Footnote 47 In “Under Fire: Are Canadian Street Cops Outgunned?,” Robert Hotston, a sergeant with the Peterborough Police, suggested that incidents involving heavily armed criminals meant that “Canadian cops are lobbying for firepower and ammunition that have a greater stopping ability.”Footnote 48 Most Canadian civilians owned long guns, not handguns, and Hotston expressed concern that police faced shooters armed with powerful shotguns and rifles. He surveyed several options available to police, including providing front-line officers with more capable revolvers.Footnote 49 By the early 1990s, authors in Blue Line increasingly argued that semi-automatic handguns were key to protecting police. They repeated many of the claims made by firearms manufacturers, such as that semi-automatic handguns were faster to load, constructed of high-tech materials, and had advanced ergonomic designs that made them easy to point and fire. Revolvers were portrayed as the tools of old-time cops, not modern police officers. Revolvers were wood-handled relics; semi-automatics were sleek and modern. A lengthy article published in Blue Line in May 1993 by Corporal Gerry Pyke of the Vancouver Police Department demonstrated the marshalling of such arguments. Pyke noted that criminals could “equip themselves with any type of weapon available whether that be a long rifle or a handgun, fully automatic (machine gun) or any varian[t] thereof.” Criminals were also aware that the police carried a handgun that “fires only six rounds while on duty.” Heavier police armaments were thus necessary. Pyke also questioned why computer equipment was replaced every few years, “while the revolvers we use are 120 years old.” It was unfair to police, in Pyke’s view, to deny police a “better, more modern handgun.”Footnote 50 In January 1994, Blue Line published an article on the history of revolvers that implicitly made the case that police needed modern semi-automatic handguns. The revolver “has reached the peak of its refinement,” and there “isn’t much more that can be done to the weapon to make it any better,” as, essentially, “the weapon itself has remained unchanged for the past 90 years.”Footnote 51 Modern law enforcement needed modern guns. Some police rejected objections to semi-automatic handguns based on the supposedly threatening appearance of the firearms. One letter writer from Alberta, in 1993, said “I have heard that people may think they look too aggressive. So what! If they are better we should have them.”Footnote 52

Several high-profile shootings of police were repeatedly invoked as evidence supporting the necessity of replacing revolvers with semi-automatic handguns. Even though the number of police officers killed on duty did not actually spike in the late 1980s and early 1990s, tragic incidents served as parables highlighting the dangers faced by front-line law enforcement and the failures of police leaders and, especially, politicians to understand those dangers and take sufficient action to ensure officer safety.Footnote 53 The most prominent episode employed by advocates of arming police with semi-automatic handguns was the death of Sudbury Constable Joseph MacDonald, who died after emptying his revolver in a gunfight with two men in 1993. Clinton Suzack, armed with a semi-automatic handgun, reportedly shot and killed MacDonald while he reloaded.Footnote 54

By the mid 1990s, the revolver versus semi-automatic pistol debate was largely settled in favour of semi-automatics on the pages of Blue Line. The magazine began to draw attention to American police forces that had adopted the new pistols, hinting that Canadian police should do the same, and published political cartoons that emphasized the importance of semi-automatic handguns to ensure police safetyFootnote 55 (see Figure 5). The journal pressed strongly for police use of semi-automatic handguns. In 1998, Blue Line published an article by its firearms training editor, Dave Brown, making the case that semi-automatic handguns were superior to revolvers. Brown was less focused on the technical differences of the two kinds of firearms than on how real-world conditions made semi-automatic handguns preferable. He suggested that the limited ammunition capacity of the revolver made police reluctant to shoot when in danger. Brown argued that an officer would freely fire one shot from a revolver if faced by danger, but “there is an enormous reluctance to fire subsequent shots. If the officer fires two, they will then be subconsciously reluctant to fire a third.” He believed the “mind knows that three shots will exhaust half the ammunition supply,” and the “subconscious mind is very much aware of how difficult it is to reload the revolver under stress.” Brown concluded that this “psychological ‘freeze’ may be just enough time for the officer to lose the fight.” On the other hand, the semi-automatic handgun “provides a comfortable margin of self-confidence at a time where it is critical that the officer gain every tiny advantage possible.”Footnote 56 This was because semi-automatic handguns carried more rounds of ammunition, and because reloading a revolver required fine motor skills that degraded under stress, while semi-automatic guns could be reloaded much more easily, even in difficult situations.

Figure 5. In this 1993 cartoon, Blue Line suggests that revolvers placed police in danger when faced with well-armed criminals. Source: Blue Line, January 1993, 3. Reproduced with the permission of Blue Line.

The Transition to Semi-Automatic Police Handguns

Beginning in the early 1990s, semi-automatic handguns began to replace service revolvers as the sidearms of Canadian police. Some SWAT forces had already received semi-automatic handguns, opening the door to their use by all police. In 1989, for instance, a review of police tactical units in Ontario recommended that team members be issued semi-automatic handguns.Footnote 57 Developments in several provinces illustrate the relatively quick adoption of semi-automatic handguns for police despite some public apprehension. Alberta took the lead in providing all members of municipal police forces with semi-automatics. In 1992 a firearms committee of the Calgary police recommended the adoption of such weapons.Footnote 58 There was some resistance to this move. The Calgary Herald asked the police committee why it was “recommending arming Calgary constables with a semi-automatic weapon more suitable for house to house combat than the peaceable maintenance of law and order?”Footnote 59 The Calgary police nevertheless became the first service to fully transfer to semi-automatic handguns when its members were armed with Glock pistols.Footnote 60 The Edmonton police soon received semi-automatic handguns, and by 1993 the Medicine Hat police also made the switch.Footnote 61 The desire to be a modern force was evident in the decisions to adopt semi-automatic handguns. In Medicine Hat, for instance, a local inspector said of the Medicine Hat police, “Although we are not as large as many police forces, [we] pride ourselves in being the pioneer of weapons transition in Canada.”Footnote 62

In British Columbia, a committee consisting of representatives from police organizations studied the appropriateness of different handguns for police and, in early 1993, recommended the purchase of Beretta semi-automatic pistols.Footnote 63 The shift to semi-automatic handguns in British Columbia received a boost when heavily armed thieves robbed a Vancouver jewelry store. This led the Times Colonist to note that police felt that the .38 calibre revolver was an antique. The newspaper concluded that the “men and women who lay their lives on the line for us every day deserve a more effective weapon.”Footnote 64 Then, in 1994, a commission of inquiry into policing in the province issued its recommendations, which included upgraded police handguns. British Columbia police organizations had told the commission that revolvers should be replaced with semi-automatic handguns to protect officers and the public. The British Columbia Civil Liberties Association initially opposed the change to semi-automatic handguns, in part because it deemed increasing police firepower unnecessary. The commission nevertheless recommended that the police be permitted semiautomatic handguns.Footnote 65 In early 1995, the New Democratic government of British Columbia announced that the province’s independent municipal police forces would replace revolvers with semi-automatic handguns.Footnote 66

In Ontario, the shift to semi-automatic handguns proved especially controversial. The province’s Progressive Conservative Party positioned itself as a “law and order” party in the early 1990s, a time when the public expressed considerable concern with crime.Footnote 67 Jennifer Carlson suggests that, as crime becomes a “central social concern worthy of militaristic response, the state breeds suspicion regarding its own efficacy to take on the slippery, but mammoth, task of crime suppression.”Footnote 68 Carlson uses this insight to help explain the tendency of citizens to arm themselves; however, it also explains the desire to strengthen police by providing new firearms. Some Progressive Conservative leaders urged the governing NDP to provide police with semi-automatic pistols. In a 1991 debate over amendments to the Police Services Act,Footnote 69 member of provincial parliament (MPP) Bob Runciman highlighted the problem of violent crime and said the NDP lacked solutions, including the provision of adequate weapons to police. Police “have to go into some areas of Metro Toronto and be faced with semi-automatic weapons. What do police officers in Toronto have? When they talk about getting better weaponry, what kind of approach do we get from the Solicitor General and the Attorney General? Absolute silence.”Footnote 70 In December 1991, the Metropolitan Toronto Police Service Board approved the purchase of 400 semi-automatic handguns to help counter the threat posed by dangerous weapons in the hands of those involved in the illegal drug trade. The new police guns were to be distributed to officers working in drug investigations and in foot patrols in high-risk areas.Footnote 71 Well-known Toronto lawyer Clayton Ruby warned against adopting new handguns: “Increasing firepower will merely increase the danger to the public that arises when one poorly trained person faces down another armed with deadly weaponry.”Footnote 72 In October 1993, Progressive Conservative MPP (and future premier) Mike Harris raised the death of Constable MacDonald, while Runciman pressed the government to accede to police requests for semi-automatic handguns. Runciman also raised the death of Constable MacDonald, saying that “equipping officers with the semiautomatic handgun might have made a difference in this particular situation.”Footnote 73 The NDP solicitor general, however, would only say that the issue was under consideration.

An important decision in 1993 by the Ontario Ministry of Labour contributed to the provision of semi-automatic handguns to the province’s police. In 1991, Constable Cam Woolley confronted a heavily armed man near Caledon, Ontario. Constable Woolley emptied his revolver, then found himself in a ditch unable to quickly reload. Luckily, Woolley survived the incident, but afterwards he complained to the provincial ministry of labour that his service revolver was inadequate equipment that made his workplace unsafe.Footnote 74 The labour ministry subsequently found that revolvers were too slow to load and had problems of involuntary cocking and discharge. The ministry thus ordered that the province authorize the acquisition of semi-automatic handguns for police.Footnote 75 Blue Line editor Lymburner claimed that this was the “first time in Canada or the United States that a widely used weapon had been declared legally unsafe.”Footnote 76 The opposition Progressive Conservatives used the ministry’s finding to pressure the NDP government to replace revolvers with semi-automatic handguns.Footnote 77 Lymburner suggested that the labour decision was key to the transition to semi-automatics in Ontario, and in other parts of the country. In Ontario, the order “placed every organization that armed their members at risk of civil and prosecutorial repercussions” if they did not show reasonable diligence at removing revolvers from use.Footnote 78 Lymburner also surmised that authorities in the rest of Canada had to consider the Ontario labour decision, for if police with revolvers in other provinces suffered harm, authorities in those jurisdiction would be faced with the challenge of disproving the Ontario finding that revolvers were unsafe in the police workplace.

In early 1994, the Ontario government announced amendments to the Equipment and Use of Force Regulation of the Police Services Act to come into compliance with the order issued by the Ministry of Labour.Footnote 79 Ontario Solicitor General David Christopherson explained that, “in response to a health and safety issue that directly affects police officers in this province,” the government saw fit to enact measures that “would allow police officers to move from the .38-calibre revolver, which was deemed to be unsafe in some circumstances, to the far more efficient and safer 9-millimetre or .40-calibre semi-automatic.”Footnote 80 Every police officer had to be issued a semi-automatic handgun, and the .38 calibre revolver was prohibited as a police weapon after 1999.Footnote 81 Ontario police soon began to announce choices of semi-automatic pistols. The Ontario Provincial Police received the SIG Sauer P229 pistol for its 4,500 members.Footnote 82 The York Regional Police Service (and other law enforcement agencies, including the police in Sudbury and Thunder Bay) adopted a Beretta semi-automatic pistol. Other Canadian jurisdictions followed suit and adopted semi-automatic handguns. Police in Saskatoon, Regina, Winnipeg, and Brandon all received approval for new handguns.Footnote 83 In 1995, the RCMP decided to replace its revolvers with 17,200 Smith & Wesson semi-automatic handguns.Footnote 84

Blue Line undertook an ambitious Canada-wide survey of the police transition to semi-automatic handguns, and its findings, reported in January 1996, showed how quickly most police services received new weapons. The magazine contacted the firearms industry and police services to compile details on the make and model of handguns purchased or ordered, as well as the quantity each police force had or would acquire. Blue Line found that over 180 police services had purchased 43,272 semi-automatic handguns in the previous two years.Footnote 85 Blue Line reported the results of its survey by province and police force. It found, for example, that the tiny Saanich Police had ordered nineteen Glock handguns, while the Vancouver police had ordered 1,200 Berettas. Smith & Wesson handguns were most popular (51 per cent of all reported handguns purchased), while 26 per cent were Glocks, 13 per cent were SIG Sauer handguns, nine per cent were Berettas, and one per cent were produced by other manufacturers. For gun makers, there remained money to be made in the police market in Canada, as Blue Line estimated that over 31,000 police were still using revolvers. One important outlier was the Sûreté du Québec.Footnote 86 Holdout police forces, however, quickly succumbed and switched to semi-automatic handguns. In 2001, it was announced that the Sûreté du Québec (and the Montréal police) would acquire semi-automatic handguns.Footnote 87 In 2003, Blue Line completed another survey of handguns used by police and declared that the revolver was “almost completely extinct among Canadian police agencies.”Footnote 88

Conclusion

In the 1990s, Canadian police forces and organizations representing law enforcement demanded the provision of semi-automatic handguns that could fire faster and be reloaded more quickly. Police invoked memories of dead officers to support their arguments and employed workplace safety concerns to press their position. The gun industry encouraged the transition to semi-automatic firearms, both because the police market for firearms was large and because the adoption of these weapons by law enforcement would also normalize them for the civilian market. As demonstrated in the advertisements that appeared in Blue Line during the 1990s, the firearms industry portrayed semi-automatic handguns as more effective, faster to reload, more durable, and more modern than traditional police revolvers. They subtly or blatantly alluded to the military uses of such guns, blurring the line between policing weapons and weapons of war and contributing to the often criticized militarization of Canadian policing. Once some police forces transitioned to semi-automatic handguns, it proved very difficult for authorities in other jurisdictions to resist efforts to adopt these weapons. Concerns that semi-automatic handguns offered excessive levels of firepower were swept aside. The trusty revolver, which many police had carried for decades, was dumped in favour of the sleek semi-automatic handgun.

The long-term implications of arming police with semi-automatic handguns are still unfolding. As noted earlier, some critics in the 1990s expressed concern that arming police with these firearms would lead to more civilian deaths. Recent shootings by police have garnered considerable public attention, such as when Edmundston police fatally shot Chantal Moore in 2020, an Indigenous woman, during a wellness check. Scholarship on policing notes the large number of Black men and Indigenous people killed in encounters with police.Footnote 89 Canada lacks a national database of deaths caused by police, let alone a database that accurately traces what kinds of firearms police used in deadly encounters. The research that does exist, however, suggests that fatal encounters with police rose from an average of 22.7 per year in the 2000–2010 period to 37.8 per year from 2011 to 2022, a 66.5 percent increase.Footnote 90 Explaining this growth is undoubtedly complicated and requires further study, but one factor that should be considered is the change in police firearms.