1 Introduction

Let

![]() $\mathbb {D}:=\{z\in \mathbb {C}:\vert z\vert <1\}$

denote the open unit disk, let

$\mathbb {D}:=\{z\in \mathbb {C}:\vert z\vert <1\}$

denote the open unit disk, let

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}=\{z\in {\mathbb {C}}:\, \vert z\vert =1\}$

denote the unit circle, and let

${\mathbb {T}}=\{z\in {\mathbb {C}}:\, \vert z\vert =1\}$

denote the unit circle, and let

![]() $H(\mathbb {D})$

be the Fréchet space consisting of all holomorphic functions on

$H(\mathbb {D})$

be the Fréchet space consisting of all holomorphic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

endowed with the topology of uniform convergence on all compact subsets of

$\mathbb {D}$

endowed with the topology of uniform convergence on all compact subsets of

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

. When one is interested in the boundary behavior of a holomorphic function f in

$\mathbb {D}$

. When one is interested in the boundary behavior of a holomorphic function f in

![]() ${\mathbb {D}}$

, one can look at the behavior on

${\mathbb {D}}$

, one can look at the behavior on

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

of the partial sums of the Taylor expansion of f at

${\mathbb {T}}$

of the partial sums of the Taylor expansion of f at

![]() $0$

, or one can look at the behavior of

$0$

, or one can look at the behavior of

![]() $f(z)$

when z in

$f(z)$

when z in

![]() ${\mathbb {D}}$

approaches

${\mathbb {D}}$

approaches

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

. In the second case, the notion of cluster set of f at z comes naturally into play. Let us recall that if

${\mathbb {T}}$

. In the second case, the notion of cluster set of f at z comes naturally into play. Let us recall that if

![]() $\gamma :[0,1)\to {\mathbb {D}}$

is a continuous path to a boundary point of

$\gamma :[0,1)\to {\mathbb {D}}$

is a continuous path to a boundary point of

![]() ${\mathbb {D}}$

(that is,

${\mathbb {D}}$

(that is,

![]() $\gamma (r)\to z \in {\mathbb {T}}$

as

$\gamma (r)\to z \in {\mathbb {T}}$

as

![]() $r\to 1$

), the cluster set of f along

$r\to 1$

), the cluster set of f along

![]() $\gamma $

is defined as

$\gamma $

is defined as

In complex function theory, it is of great interest to distinguish and study classes of holomorphic functions with a regular boundary behavior. Regular boundary behavior at a point of

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

can mean, for instance, convergence, Cesàro summability, or Abel summability of the Taylor expansion at this point. We recall that a function f in

${\mathbb {T}}$

can mean, for instance, convergence, Cesàro summability, or Abel summability of the Taylor expansion at this point. We recall that a function f in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

is Abel summable at

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

is Abel summable at

![]() $\zeta \in {\mathbb {T}}$

if the quantity

$\zeta \in {\mathbb {T}}$

if the quantity

![]() $f(r\zeta )$

,

$f(r\zeta )$

,

![]() $r\in [0,1)$

, has a finite limit as

$r\in [0,1)$

, has a finite limit as

![]() $r\to 1$

. Note that in the latter case, the cluster set of f along the radius

$r\to 1$

. Note that in the latter case, the cluster set of f along the radius

![]() $\{r\zeta :\,r\in [0,1)\}$

is reduced to a single value. Yet, it is now well understood that nonregularity is a generic behavior. We say that a property is generic in a Baire space X if the set of those

$\{r\zeta :\,r\in [0,1)\}$

is reduced to a single value. Yet, it is now well understood that nonregularity is a generic behavior. We say that a property is generic in a Baire space X if the set of those

![]() $x\in X$

which satisfy this property contains a countable intersection of dense open sets. For example, it was already observed in 1933 that the set of functions whose cluster sets along any radius is equal to

$x\in X$

which satisfy this property contains a countable intersection of dense open sets. For example, it was already observed in 1933 that the set of functions whose cluster sets along any radius is equal to

![]() ${\mathbb {C}}$

, is residual in

${\mathbb {C}}$

, is residual in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

[Reference Kierst and Szpilrajn30]. In 2008, it was even shown that the set—denoted by

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

[Reference Kierst and Szpilrajn30]. In 2008, it was even shown that the set—denoted by

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

—of those functions

${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

—of those functions

![]() $f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

satisfying the previous property along any (continuous) path

$f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

satisfying the previous property along any (continuous) path

![]() $\gamma :[0,1)\to {\mathbb {D}}$

having some limit

$\gamma :[0,1)\to {\mathbb {D}}$

having some limit

![]() $\zeta \in {\mathbb {T}}$

at

$\zeta \in {\mathbb {T}}$

at

![]() $1$

is residual in

$1$

is residual in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

[Reference Bernal-González, Calderón and Prado-Bassas8]. More recently, the first author exhibited in [Reference Charpentier12] another residual set of functions in

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

[Reference Bernal-González, Calderón and Prado-Bassas8]. More recently, the first author exhibited in [Reference Charpentier12] another residual set of functions in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

with a boundary behavior at least as wild as those of

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

with a boundary behavior at least as wild as those of

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

. Let

${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

. Let

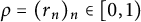

![]() $\varrho :=(r_n)_n \subset [0,1)$

be a sequence convergent to

$\varrho :=(r_n)_n \subset [0,1)$

be a sequence convergent to

![]() $1$

and denote by

$1$

and denote by

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

the set of those

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

the set of those

![]() $f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

that satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

that satisfy the following property: for any compact set

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

, the set

${\mathbb {T}}$

, the set

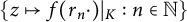

![]() $\{f_{r_n}|_K:\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

is dense in the space

$\{f_{r_n}|_K:\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

is dense in the space

![]() ${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

of all continuous functions on K endowed with the uniform topology. Here, for

${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

of all continuous functions on K endowed with the uniform topology. Here, for

![]() $r\in [0,1)$

, we denote by

$r\in [0,1)$

, we denote by

![]() $f_r$

the function given by

$f_r$

the function given by

![]() $f_r(z)=f(rz)$

,

$f_r(z)=f(rz)$

,

![]() $rz\in {\mathbb {D}}$

. It was then observed in [Reference Charpentier12] that

$rz\in {\mathbb {D}}$

. It was then observed in [Reference Charpentier12] that

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

is residual in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

is residual in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

and that

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

and that

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\subset {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

. At this point, we would like to introduce another natural class of universal functions, defined on the model of

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\subset {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

. At this point, we would like to introduce another natural class of universal functions, defined on the model of

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

but independent of the choice of a sequence

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

but independent of the choice of a sequence

![]() $\varrho $

. Precisely, let

$\varrho $

. Precisely, let

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

denote the set of all functions f in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

denote the set of all functions f in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

satisfying that, given any compact set

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

satisfying that, given any compact set

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

and any

${\mathbb {T}}$

and any

![]() $h\in {\mathcal {C}}(K)$

, there exists

$h\in {\mathcal {C}}(K)$

, there exists

![]() $(r_n)_n\subset [0,1)$

tending to

$(r_n)_n\subset [0,1)$

tending to

![]() $1$

such that

$1$

such that

![]() $f_{r_n}$

approximates h uniformly on K. One can easily checks that

$f_{r_n}$

approximates h uniformly on K. One can easily checks that

In the whole paper, the elements of

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

will be referred to as

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

will be referred to as

![]() $\varrho $

-Abel universal functions, and those of

$\varrho $

-Abel universal functions, and those of

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

as Abel universal functions. For the interested readers, we should mention the papers [Reference Bayart2, Reference Charpentier and Kosiński14] where universal boundary phenomena for holomorphic functions in several complex variables are exhibited and [Reference Abakumov, Nestoridis and Picardello1] where universal boundary behavior for harmonic functions on trees are studied.

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

as Abel universal functions. For the interested readers, we should mention the papers [Reference Bayart2, Reference Charpentier and Kosiński14] where universal boundary phenomena for holomorphic functions in several complex variables are exhibited and [Reference Abakumov, Nestoridis and Picardello1] where universal boundary behavior for harmonic functions on trees are studied.

For those who are familiar with the topic, the property enjoyed by the functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

evokes that enjoyed by the well-studied universal Taylor series. In 1996, Nestoridis proved that there exists a residual set

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

evokes that enjoyed by the well-studied universal Taylor series. In 1996, Nestoridis proved that there exists a residual set

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

of functions f in

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

of functions f in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

such that for any compact set

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

such that for any compact set

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

, with connected complement, the set

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

, with connected complement, the set

![]() $\{S_n(f)|_K:\, n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

of all partial sums of the Taylor expansion of f at

$\{S_n(f)|_K:\, n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

of all partial sums of the Taylor expansion of f at

![]() $0$

is dense in

$0$

is dense in

![]() ${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

[Reference Nestoridis39]. Let us denote by

${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

[Reference Nestoridis39]. Let us denote by

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

the set of those functions

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

the set of those functions

![]() $f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

satisfying the previous property not for any compact set

$f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

satisfying the previous property not for any compact set

![]() $K\in {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement, but only for all compact sets

$K\in {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement, but only for all compact sets

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

. Note that

${\mathbb {T}}$

. Note that

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\subset {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

. The functions in

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\subset {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

. The functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

were extensively studied from many points of view. We refer to [Reference Bayart3, Reference Bayart, Grosse-Erdmann, Nestoridis and Papadimitropoulos6, Reference Charpentier and Mouze15, Reference Costakis, Jung and Müller22–Reference Gardiner and Manolaki25, Reference Melas and Nestoridis33, Reference Melas, Nestoridis and Papadoperakis34, Reference Mouze36] and the references therein for a nonexhaustive list of papers. In particular, some of these highlight the fact that functions in

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

were extensively studied from many points of view. We refer to [Reference Bayart3, Reference Bayart, Grosse-Erdmann, Nestoridis and Papadimitropoulos6, Reference Charpentier and Mouze15, Reference Costakis, Jung and Müller22–Reference Gardiner and Manolaki25, Reference Melas and Nestoridis33, Reference Melas, Nestoridis and Papadoperakis34, Reference Mouze36] and the references therein for a nonexhaustive list of papers. In particular, some of these highlight the fact that functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

enjoy irregular boundary behavior, for example, along radii. In comparison, the recently introduced Abel universal functions were considered in two papers [Reference Charpentier12, Reference Maronikolakis32]. In [Reference Charpentier12], the first author sketched a comparison of the sets

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

enjoy irregular boundary behavior, for example, along radii. In comparison, the recently introduced Abel universal functions were considered in two papers [Reference Charpentier12, Reference Maronikolakis32]. In [Reference Charpentier12], the first author sketched a comparison of the sets

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

and

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

and

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

and noticed that the main results of [Reference Costakis20, Reference Gehlen, Luh and Müller26] actually imply that none of them is included in the other. More precisely, the assertion

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

and noticed that the main results of [Reference Costakis20, Reference Gehlen, Luh and Müller26] actually imply that none of them is included in the other. More precisely, the assertion

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\setminus {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

was derived from the fact that the partial sums of the functions in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\setminus {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

was derived from the fact that the partial sums of the functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

have to behave wild not only at the boundary of

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

have to behave wild not only at the boundary of

![]() ${\mathbb {D}}$

, but also on compact sets as far as possible from

${\mathbb {D}}$

, but also on compact sets as far as possible from

![]() $0$

. This thus leads to ask rather if

$0$

. This thus leads to ask rather if

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

and

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

and

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

or

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

or

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

are comparable. The question was explicitly stated in [Reference Charpentier12].

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

are comparable. The question was explicitly stated in [Reference Charpentier12].

The first goal of this paper is to show that neither

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

nor

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

nor

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

is comparable to

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

is comparable to

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

and that

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

and that

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

, making it interesting to study independently the functions in

${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

, making it interesting to study independently the functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

or

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

or

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

. It is worth mentioning that, whereas exhibiting generic functions with universal behavior is rather standard, building nongeneric functions that still enjoy some universal property can be very tricky. This is probably why there are very few results of this type. For example, in order to build up a function in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

. It is worth mentioning that, whereas exhibiting generic functions with universal behavior is rather standard, building nongeneric functions that still enjoy some universal property can be very tricky. This is probably why there are very few results of this type. For example, in order to build up a function in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

which is not in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

which is not in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

, we will make use of a purely constructive trick. In passing, we will observe that this trick can turn out to be useful in order to attack one of the most important open questions about universal series: does the derivative of a universal Taylor series remain a universal Taylor series? We will build functions in

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

, we will make use of a purely constructive trick. In passing, we will observe that this trick can turn out to be useful in order to attack one of the most important open questions about universal series: does the derivative of a universal Taylor series remain a universal Taylor series? We will build functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

with partial sums simultaneously enjoying a universal property outside

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

with partial sums simultaneously enjoying a universal property outside

![]() $\overline {{\mathbb {D}}}$

, and whose derivative is not even in

$\overline {{\mathbb {D}}}$

, and whose derivative is not even in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

. Let us observe that by Weierstrass’ theorem, it is easily seen that if

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

. Let us observe that by Weierstrass’ theorem, it is easily seen that if

![]() $\{S_n(f)|_K:\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

is dense in

$\{S_n(f)|_K:\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

is dense in

![]() ${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

for any

${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

for any

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus \overline {{\mathbb {D}}}$

, then so is

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus \overline {{\mathbb {D}}}$

, then so is

![]() $\{S_n(f')|_K:\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

. The same question makes sense for

$\{S_n(f')|_K:\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

. The same question makes sense for

![]() $\varrho $

-Abel universal functions. In this context, we will be able to exhibit functions in

$\varrho $

-Abel universal functions. In this context, we will be able to exhibit functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

whose derivative is not in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

whose derivative is not in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

, answering a question also posed in [Reference Charpentier12].

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

, answering a question also posed in [Reference Charpentier12].

Being now convinced that the notions of universal Taylor series and Abel universal functions are quite distinct, it is legitimate to consider the study of the second one for itself. Like universal Taylor series, Abel universal functions are natural examples within the large theory of universality in operator theory. Let us say that, given two Fréchet spaces X et Y, a family

![]() $(T_i)_{i\in I}$

of continuous operators from X to Y is universal if there exists

$(T_i)_{i\in I}$

of continuous operators from X to Y is universal if there exists

![]() $x\in X$

such that the set

$x\in X$

such that the set

is dense in Y. Such a vector x is said to be universal for

![]() $(T_i)_{i\in I}$

. Most of the concrete examples of universal families of operators fall into the situation where

$(T_i)_{i\in I}$

. Most of the concrete examples of universal families of operators fall into the situation where

![]() $I={\mathbb {N}}$

,

$I={\mathbb {N}}$

,

![]() $X=Y$

, and

$X=Y$

, and

![]() $T_n=T^n$

,

$T_n=T^n$

,

![]() $n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, where T is a continuous operator from X to X. In this case, the operator T is called hypercyclic whenever

$n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, where T is a continuous operator from X to X. In this case, the operator T is called hypercyclic whenever

![]() $(T^n)_n$

is universal and the notion lies within linear dynamics, a very active branch of operator theory. Apart from this setting, there are some other natural families of operators that are universal [Reference Bayart, Grosse-Erdmann, Nestoridis and Papadimitropoulos6, Reference Grosse Erdmann28]. By natural families of operators, we mean families of operators which naturally come into play in mathematical analysis. This is in particular the case of the family

$(T^n)_n$

is universal and the notion lies within linear dynamics, a very active branch of operator theory. Apart from this setting, there are some other natural families of operators that are universal [Reference Bayart, Grosse-Erdmann, Nestoridis and Papadimitropoulos6, Reference Grosse Erdmann28]. By natural families of operators, we mean families of operators which naturally come into play in mathematical analysis. This is in particular the case of the family

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K:=\{T_{\varrho ,n}^K:\, n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

(resp.

${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K:=\{T_{\varrho ,n}^K:\, n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

(resp.

![]() $\mathcal {S} ^K:= \{S_n^K:\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

) defined, for a compact set

$\mathcal {S} ^K:= \{S_n^K:\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

) defined, for a compact set

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

(resp.

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

(resp.

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

), by

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

), by

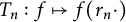

$$ \begin{align*} T_{\varrho,n}^K:\left\{\begin{array}{lll}H({\mathbb{D}}) & \to & {\mathcal{C}}(K)\\ f & \mapsto & f_{r_n}|_K \end{array} \right. \quad \left( \text{resp. } S_n^K:\left\{\begin{array}{lll}H({\mathbb{D}}) & \to & {\mathcal{C}}(K)\\ f=\sum_ka_kz^k & \mapsto & \sum_{k=0}^na_kz^k|_K \end{array} \right.\right)\!, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} T_{\varrho,n}^K:\left\{\begin{array}{lll}H({\mathbb{D}}) & \to & {\mathcal{C}}(K)\\ f & \mapsto & f_{r_n}|_K \end{array} \right. \quad \left( \text{resp. } S_n^K:\left\{\begin{array}{lll}H({\mathbb{D}}) & \to & {\mathcal{C}}(K)\\ f=\sum_ka_kz^k & \mapsto & \sum_{k=0}^na_kz^k|_K \end{array} \right.\right)\!, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\varrho =(r_n)_n$

is a given sequence in

$\varrho =(r_n)_n$

is a given sequence in

![]() $[0,1)$

tending to

$[0,1)$

tending to

![]() $1$

. According to the definitions given in the first part of the introduction, the elements of

$1$

. According to the definitions given in the first part of the introduction, the elements of

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

with

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

with

![]() $\varrho =(r_n)_n$

(resp.

$\varrho =(r_n)_n$

(resp.

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

) appear as functions in

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

) appear as functions in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

that are universal for all families

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

that are universal for all families

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K$

,

${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K$

,

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

(resp.

${\mathbb {T}}$

(resp.

![]() $\mathcal {S}^K$

,

$\mathcal {S}^K$

,

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {C}} \setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement). Let us observe that the sequences

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}} \setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement). Let us observe that the sequences

![]() $(T_{\varrho ,n}^K)_n$

are universal sequences of composition operators that fit within the framework of the recent paper [Reference Charpentier and Mouze16]. Furthermore, when I is not countable, standard examples of universal families

$(T_{\varrho ,n}^K)_n$

are universal sequences of composition operators that fit within the framework of the recent paper [Reference Charpentier and Mouze16]. Furthermore, when I is not countable, standard examples of universal families

![]() $(T_i)_{i\in I}$

are given by semigroups. Universality or hypercyclicity of semigroups has been a subject of interest during the last decade, and strong similarities with hypercyclicity of a single operator have been discovered (see [Reference Conejero, Peris and Müller18] and [Reference Bayart and Matheron7, Chapter 3]). In this context, Abel universal functions thus appear as singular and natural examples of objects that are universal for the nonsemigroup families

$(T_i)_{i\in I}$

are given by semigroups. Universality or hypercyclicity of semigroups has been a subject of interest during the last decade, and strong similarities with hypercyclicity of a single operator have been discovered (see [Reference Conejero, Peris and Müller18] and [Reference Bayart and Matheron7, Chapter 3]). In this context, Abel universal functions thus appear as singular and natural examples of objects that are universal for the nonsemigroup families

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}^K:=(T_r^K)_{r\in [0,1)}$

of operators, where K is any subset of

${\mathcal {T}}^K:=(T_r^K)_{r\in [0,1)}$

of operators, where K is any subset of

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

different from

${\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

, and

${\mathbb {T}}$

, and

![]() $T_r^K$

is defined by

$T_r^K$

is defined by

$$ \begin{align*} T_r^K:\left\{\begin{array}{lll}H({\mathbb{D}}) & \to & {\mathcal{C}}(K),\\ f & \mapsto & f_{r}|_K. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} T_r^K:\left\{\begin{array}{lll}H({\mathbb{D}}) & \to & {\mathcal{C}}(K),\\ f & \mapsto & f_{r}|_K. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

With all this in mind, it looks quite motivating to wonder which of the most interesting phenomena observed in linear dynamics can also be observed for the natural families of operators that are universal and do not fall into the concept of hypercyclicity. The remainder of this paper will focus on this program around the notion of Abel universal functions.

One of the most elegant results on hypercyclicity, due to Bourdon and Feldman [Reference Bourdon10], asserts that a vector

![]() $x\in X$

is hypercyclic for a bounded operator

$x\in X$

is hypercyclic for a bounded operator

![]() $T:X\to X$

whenever its orbit under T is somewhere dense in X. A straight consequence of this fact is a result, independently obtained earlier by Costakis [Reference Costakis21] and Peris [Reference Peris40], telling us that if for finitely many

$T:X\to X$

whenever its orbit under T is somewhere dense in X. A straight consequence of this fact is a result, independently obtained earlier by Costakis [Reference Costakis21] and Peris [Reference Peris40], telling us that if for finitely many

![]() $x_1,\ldots ,x_l\in X$

the set

$x_1,\ldots ,x_l\in X$

the set

![]() $\bigcup _{k=1}^l\{T^n (x_k):\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

is dense in X, then one of the

$\bigcup _{k=1}^l\{T^n (x_k):\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}$

is dense in X, then one of the

![]() $x_i$

’s is hypercyclic for T. Both results extend to the setting of semigroups [Reference Bayart and Matheron7]. One may now ask whether this property is also shared by sequences

$x_i$

’s is hypercyclic for T. Both results extend to the setting of semigroups [Reference Bayart and Matheron7]. One may now ask whether this property is also shared by sequences

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}^K$

or

${\mathcal {T}}^K$

or

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K$

, for some

${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K$

, for some

![]() $\varrho =(r_n)_n \subset [0,1)$

tending to

$\varrho =(r_n)_n \subset [0,1)$

tending to

![]() $1$

and

$1$

and

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

. In fact, we will constructively prove that this is not the case: given

${\mathbb {T}}$

. In fact, we will constructively prove that this is not the case: given

![]() $K_0\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K_0\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

and

${\mathbb {T}}$

and

![]() $\varrho =(r_n)_n$

, there exist two functions

$\varrho =(r_n)_n$

, there exist two functions

![]() $f_1,f_2\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

, none of them Abel universal for

$f_1,f_2\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

, none of them Abel universal for

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}^{K_0}$

, such that the set

${\mathcal {T}}^{K_0}$

, such that the set

![]() $\{T_{\varrho ,n}^{K}(f_i):\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}, i=1,2\}$

is dense in

$\{T_{\varrho ,n}^{K}(f_i):\,n\in {\mathbb {N}}, i=1,2\}$

is dense in

![]() ${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

for any compact set

${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

for any compact set

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

. As a consequence, this will also show that the families

${\mathbb {T}}$

. As a consequence, this will also show that the families

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}^K$

and

${\mathcal {T}}^K$

and

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^{K}$

do not satisfy a Bourdon–Feldman-type property. We should mention that an analogue of those results was obtained by the second author for Fekete universal series, a real-analytic variant of universal Taylor series [Reference Mouze35]. However, the case of universal Taylor series—i.e., for the sequences

${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^{K}$

do not satisfy a Bourdon–Feldman-type property. We should mention that an analogue of those results was obtained by the second author for Fekete universal series, a real-analytic variant of universal Taylor series [Reference Mouze35]. However, the case of universal Taylor series—i.e., for the sequences

![]() $\mathcal {S}^K$

,

$\mathcal {S}^K$

,

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {C}} \setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement—is still open.

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}} \setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement—is still open.

In 2006, Bayart and Grivaux [Reference Bayart and Grivaux5] introduced the notion of frequent hypercyclicity, which quickly became central in linear dynamics (see the books [Reference Bayart and Matheron7, Reference Grosse-Erdmann and Peris Manguillot29] and the recent paper [Reference Grivaux, Matheron and Menet27]). It was extended to the larger setting of universality [Reference Bonilla and Grosse-Erdmann9]. A sequence

![]() $(T_n)_n$

of continuous operators from a Fréchet space X to another one Y is said to be frequently universal if there exists

$(T_n)_n$

of continuous operators from a Fréchet space X to another one Y is said to be frequently universal if there exists

![]() $x\in X$

such that the set

$x\in X$

such that the set

![]() $\{n\in {\mathbb {N}}: T_n(x) \in U\}$

has positive lower density for any nonempty open set U of Y. For the definition of the lower density, we refer to Section 6. Roughly speaking, it quantifies the proportion of elements in

$\{n\in {\mathbb {N}}: T_n(x) \in U\}$

has positive lower density for any nonempty open set U of Y. For the definition of the lower density, we refer to Section 6. Roughly speaking, it quantifies the proportion of elements in

![]() $\{n\in {\mathbb {N}}: T_n(x) \in U\}$

among all natural numbers. The same notion makes perfectly sense for a family

$\{n\in {\mathbb {N}}: T_n(x) \in U\}$

among all natural numbers. The same notion makes perfectly sense for a family

![]() $(T_i)_{i\in I}$

of operators when I is an interval in

$(T_i)_{i\in I}$

of operators when I is an interval in

![]() ${\mathbb {R}}$

, replacing the lower density by the uniform lower density (see Section 6 for the definition). As far as we know, nondiscrete frequent universality was only considered, rather briefly, for semigroups [Reference Grosse-Erdmann and Peris Manguillot29, Chapter 7]. On the contrary, several descriptions of frequently hypercyclic operators among classes of concrete operators have been obtained [Reference Bayart and Matheron7, Reference Grosse-Erdmann and Peris Manguillot29]. In [Reference Charpentier11, Reference Mouze and Munnier37], it was observed that there cannot exist functions in

${\mathbb {R}}$

, replacing the lower density by the uniform lower density (see Section 6 for the definition). As far as we know, nondiscrete frequent universality was only considered, rather briefly, for semigroups [Reference Grosse-Erdmann and Peris Manguillot29, Chapter 7]. On the contrary, several descriptions of frequently hypercyclic operators among classes of concrete operators have been obtained [Reference Bayart and Matheron7, Reference Grosse-Erdmann and Peris Manguillot29]. In [Reference Charpentier11, Reference Mouze and Munnier37], it was observed that there cannot exist functions in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

that are frequently universal for all sequences

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

that are frequently universal for all sequences

![]() $\mathcal {S}^K$

,

$\mathcal {S}^K$

,

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {C}} \setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement. Yet, if K is fixed outside

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}} \setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement. Yet, if K is fixed outside

![]() ${\mathbb {D}}$

, it is still open whether there exist functions in

${\mathbb {D}}$

, it is still open whether there exist functions in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

frequently universal for

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

frequently universal for

![]() $\mathcal {S}^K$

. In a broad but different setting, we mention that the authors of [Reference Abakumov, Nestoridis and Picardello1] prove the existence of harmonic functions on trees with frequently universal boundary behavior.

$\mathcal {S}^K$

. In a broad but different setting, we mention that the authors of [Reference Abakumov, Nestoridis and Picardello1] prove the existence of harmonic functions on trees with frequently universal boundary behavior.

The last section of this paper is devoted to showing various results revolving around frequent Abel universality. For example, given

![]() $\varrho =(r_n)_n\subset [0,1)$

tending to

$\varrho =(r_n)_n\subset [0,1)$

tending to

![]() $1$

, we will prove a rather strong result implying that the set of all functions that are frequently universal for all sequences

$1$

, we will prove a rather strong result implying that the set of all functions that are frequently universal for all sequences

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K$

,

${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K$

,

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

(resp. for all families

${\mathbb {T}}$

(resp. for all families

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}^K$

,

${\mathcal {T}}^K$

,

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

) is a dense meagre subset of

${\mathbb {T}}$

) is a dense meagre subset of

![]() $H(\mathbb {D})$

. We will even show that there exist functions in

$H(\mathbb {D})$

. We will even show that there exist functions in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

that are frequently universal for all families

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

that are frequently universal for all families

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho (\alpha )}^K$

,

${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho (\alpha )}^K$

,

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

, where

${\mathbb {T}}$

, where

![]() $(\varrho (\alpha ))_{\alpha \in A}$

is a countable collection of pairwise disjoint sequences in

$(\varrho (\alpha ))_{\alpha \in A}$

is a countable collection of pairwise disjoint sequences in

![]() $[0,1)$

tending to

$[0,1)$

tending to

![]() $1$

. These results thus lie within the newly active topic of common frequent universality (see [Reference Bayart4, Reference Charpentier, Ernst, Mestiri and Mouze13]).

$1$

. These results thus lie within the newly active topic of common frequent universality (see [Reference Bayart4, Reference Charpentier, Ernst, Mestiri and Mouze13]).

The paper is organized as follows. The next section gathers some basic materials and definitions that will be used all along the paper. In Section 3, we prove that all the classical notions of universal functions are distinct. Section 4 deals with the nonstability of the classes of Abel universal functions under the action of the differentiation operator. In Sections 5 and 6, we focus on the “dynamical” properties of the sequences

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K$

and

${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }^K$

and

![]() ${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }$

with respect to the concept of multiuniversality and (common) frequent universality, respectively.

${\mathcal {T}}_{\varrho }$

with respect to the concept of multiuniversality and (common) frequent universality, respectively.

2 Preliminaries

The aim of this section is to introduce once and for all, the notations and objects that will be used often in the paper. We start with general notations. The letter

![]() ${\mathbb {N}}$

will stand for the set

${\mathbb {N}}$

will stand for the set

![]() $\{0,1,2,3,\ldots \}$

of all nonnegative integers. A sequence of general terms

$\{0,1,2,3,\ldots \}$

of all nonnegative integers. A sequence of general terms

![]() $u_n$

,

$u_n$

,

![]() $n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, will be denoted by

$n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, will be denoted by

![]() $(u_n)_n$

. If P is any polynomial, we will denote by

$(u_n)_n$

. If P is any polynomial, we will denote by

![]() $\text {deg}(P)$

its degree and by

$\text {deg}(P)$

its degree and by

![]() $\text {val}(P)$

its valuation. If

$\text {val}(P)$

its valuation. If

![]() $E\subset {\mathbb {C}}$

, the notation

$E\subset {\mathbb {C}}$

, the notation

![]() $\text {int}(E)$

will stand for the set of all interior points of E. For any

$\text {int}(E)$

will stand for the set of all interior points of E. For any

![]() $r\geq 0$

and

$r\geq 0$

and

![]() $E\subset {\mathbb {C}}$

, we will denote by

$E\subset {\mathbb {C}}$

, we will denote by

![]() $rE$

the set

$rE$

the set

![]() $\{rz:\, z\in E\}$

. For

$\{rz:\, z\in E\}$

. For

![]() $a\in {\mathbb {C}}$

and

$a\in {\mathbb {C}}$

and

![]() $r\geq 0$

, the open disk centered at a with radius r will be denoted by

$r\geq 0$

, the open disk centered at a with radius r will be denoted by

![]() $D(a,r)$

.

$D(a,r)$

.

Let us now focus on more specific notations. In the whole paper,

![]() $\varrho =(r_n)_n$

denotes an arbitrary sequence in

$\varrho =(r_n)_n$

denotes an arbitrary sequence in

![]() $[0,1)$

converging to

$[0,1)$

converging to

![]() $1$

. For

$1$

. For

![]() $r\in [0,1)$

we denote by

$r\in [0,1)$

we denote by

![]() $\phi _r$

the function defined by

$\phi _r$

the function defined by

![]() $z\mapsto rz$

,

$z\mapsto rz$

,

![]() $z\in \mathbb {C}$

. Without possible confusions, we will use the same notation to denote a function defined in a set

$z\in \mathbb {C}$

. Without possible confusions, we will use the same notation to denote a function defined in a set

![]() $E\subset {\mathbb {C}}$

and its restriction to a subset of E. Given a compact set

$E\subset {\mathbb {C}}$

and its restriction to a subset of E. Given a compact set

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

, different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

, different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

, we will denote by

${\mathbb {T}}$

, we will denote by

![]() ${\mathcal {V}}(K)$

a countable set of nonempty open sets defining the topology of

${\mathcal {V}}(K)$

a countable set of nonempty open sets defining the topology of

![]() ${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

.

${\mathcal {C}}(K)$

.

With these notations, the definition of Abel universal functions can be reformulated as follows.

Definition 2.1 A function

![]() $f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

is called

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

is called

![]() $\varrho $

-Abel universal if for any compact set

$\varrho $

-Abel universal if for any compact set

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

, and any

${\mathbb {T}}$

, and any

![]() $V\in {\mathcal {V}}(K)$

, the set

$V\in {\mathcal {V}}(K)$

, the set

is nonempty (or equivalently infinite), where

![]() $\phi _n:=\phi _{r_n}$

.

$\phi _n:=\phi _{r_n}$

.

We recall that the set

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

of

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

of

![]() $\varrho $

-Abel universal functions is a dense

$\varrho $

-Abel universal functions is a dense

![]() $G_{\delta }$

-subset of

$G_{\delta }$

-subset of

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

[Reference Charpentier12]. Similarly, the definition of an Abel universal functions given in the introduction is equivalent to the following one.

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

[Reference Charpentier12]. Similarly, the definition of an Abel universal functions given in the introduction is equivalent to the following one.

Definition 2.2 A function

![]() $f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

is called Abel universal if for any compact set

$f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

is called Abel universal if for any compact set

![]() $K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

different from

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

, and any

${\mathbb {T}}$

, and any

![]() $V\in {\mathcal {V}}(K)$

, the set

$V\in {\mathcal {V}}(K)$

, the set

is nonempty.

Clearly,

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\subset {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

, where

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\subset {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

, where

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

is the set of all Abel universal functions. Note also that if

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

is the set of all Abel universal functions. Note also that if

![]() $f\in {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

, then

$f\in {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

, then

![]() $1$

is a limit point of

$1$

is a limit point of

![]() $N_f(V,K)$

, for any V and K.

$N_f(V,K)$

, for any V and K.

We introduce the following technical notations that will be used in most of the proofs:

-

•

$(\varphi _n)_n$

denotes an enumeration of all polynomials with coefficients whose real and imaginary parts are rational.

$(\varphi _n)_n$

denotes an enumeration of all polynomials with coefficients whose real and imaginary parts are rational. -

•

$(K_n)_n$

denotes a sequence of compact subsets of

$(K_n)_n$

denotes a sequence of compact subsets of

${\mathbb {T}}$

, with connected complement, such that for any compact set

${\mathbb {T}}$

, with connected complement, such that for any compact set

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

, different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

, different from

${\mathbb {T}}$

, there exists

${\mathbb {T}}$

, there exists

$n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

such that

$n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

such that

$K\subset K_n$

(see, e.g., [Reference Charpentier12] for the existence of such sequence).

$K\subset K_n$

(see, e.g., [Reference Charpentier12] for the existence of such sequence). -

•

$(\varepsilon _n)_n$

denotes a decreasing sequence of positive real numbers such that

$(\varepsilon _n)_n$

denotes a decreasing sequence of positive real numbers such that

$\sum _n\varepsilon _n < 1$

. The speed of decrease of

$\sum _n\varepsilon _n < 1$

. The speed of decrease of

$(\varepsilon _n)_n$

may change from a proof to another, and will be specified if necessary.

$(\varepsilon _n)_n$

may change from a proof to another, and will be specified if necessary. -

•

$\alpha ,\beta : {\mathbb {N}} \to {\mathbb {N}}$

denote two functions such that for any

$\alpha ,\beta : {\mathbb {N}} \to {\mathbb {N}}$

denote two functions such that for any

$n,m\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, there exists an increasing sequence

$n,m\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, there exists an increasing sequence

$(n_l)_l\subset {\mathbb {N}}$

such that

$(n_l)_l\subset {\mathbb {N}}$

such that

$\alpha (n_l)=n$

and

$\alpha (n_l)=n$

and

$\beta (n_l)=m$

for any

$\beta (n_l)=m$

for any

$l\in {\mathbb {N}}$

.

$l\in {\mathbb {N}}$

.

All these notations will be tacitly used throughout the paper.

The purpose of the next sections is twofold: first, to compare the sets

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

and

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

and

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

with other classical sets of analytic functions in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})$

with other classical sets of analytic functions in

![]() ${\mathbb {D}}$

with universal behavior at the boundary; second, to study Abel universal functions, in particular with respect to classical notions coming from linear dynamics.

${\mathbb {D}}$

with universal behavior at the boundary; second, to study Abel universal functions, in particular with respect to classical notions coming from linear dynamics.

3 Abel universal functions among universal holomorphic functions

For

![]() $f=\sum _ka_kz^k \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

and

$f=\sum _ka_kz^k \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

and

![]() $n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, we denote by

$n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, we denote by

![]() $S_n(f)$

the nth partial sum of the Taylor expansion of f at

$S_n(f)$

the nth partial sum of the Taylor expansion of f at

![]() $0$

, i.e.,

$0$

, i.e.,

![]() $S_n(f)=\sum _{k=0}^na_kz^k$

.

$S_n(f)=\sum _{k=0}^na_kz^k$

.

Let us recall more explicitly the definitions of the classes of universal holomorphic functions that we intend to compare with that of Abel universal functions. The first one consists of universal Taylor series.

Definition 3.1 (Universal Taylor series)

-

(1) We denote by

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

the set of those functions

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

the set of those functions

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement, and any function

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement, and any function

$\varphi $

continuous on K and holomorphic in its interior, there exists an increasing sequence

$\varphi $

continuous on K and holomorphic in its interior, there exists an increasing sequence

$(\lambda _n)_n$

of integers such that

$(\lambda _n)_n$

of integers such that  $$ \begin{align*} \sup_{\zeta \in K}\left\vert S_{\lambda_n}(f)(\zeta) -\varphi (\zeta) \right\vert \to 0 \quad \text{as }n\to \infty. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \sup_{\zeta \in K}\left\vert S_{\lambda_n}(f)(\zeta) -\varphi (\zeta) \right\vert \to 0 \quad \text{as }n\to \infty. \end{align*} $$

The elements of

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

are called universal Taylor series.

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

are called universal Taylor series. -

(2) We denote by

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

the set of those functions

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

the set of those functions

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

, different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

, different from

${\mathbb {T}}$

, and any function

${\mathbb {T}}$

, and any function

$\varphi $

continuous on K, there exists an increasing sequence

$\varphi $

continuous on K, there exists an increasing sequence

$(\lambda _n)_n$

of integers such that

$(\lambda _n)_n$

of integers such that  $$ \begin{align*} \sup_{\zeta \in K}\left\vert S_{\lambda_n}(f)(\zeta) -\varphi (\zeta) \right\vert \to 0 \quad \text{as }n\to \infty. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \sup_{\zeta \in K}\left\vert S_{\lambda_n}(f)(\zeta) -\varphi (\zeta) \right\vert \to 0 \quad \text{as }n\to \infty. \end{align*} $$

The elements of

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

will be called

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

will be called

${\mathbb {T}}$

-universal Taylor series.

${\mathbb {T}}$

-universal Taylor series.

As already said, the radial limit of a function holomorphic in

![]() $\mathbb {D}$

at a boundary point along an increasing sequence

$\mathbb {D}$

at a boundary point along an increasing sequence

![]() $(r_n)_n$

tending to

$(r_n)_n$

tending to

![]() $1$

can be seen as the operation on the Taylor partial sums at

$1$

can be seen as the operation on the Taylor partial sums at

![]() $0$

of this function by a regular process of summation. Indeed, one can write

$0$

of this function by a regular process of summation. Indeed, one can write

![]() $f(r_nz)=\sum _{k} a_kr_n^kz^k=\sum _{k} c_{n,k} S_k(f)$

with

$f(r_nz)=\sum _{k} a_kr_n^kz^k=\sum _{k} c_{n,k} S_k(f)$

with

![]() $c_{n,k}=r_n^k(1-r_n)$

. One can check that this process of summation is regular (see [Reference Zygmund42]). Now, it turns out that the universality of a holomorphic function in

$c_{n,k}=r_n^k(1-r_n)$

. One can check that this process of summation is regular (see [Reference Zygmund42]). Now, it turns out that the universality of a holomorphic function in

![]() ${\mathbb {D}}$

is often preserved by the action of a summation process. It is in particular the case that the Cesàro means of the Taylor partial sums of an analytic function in

${\mathbb {D}}$

is often preserved by the action of a summation process. It is in particular the case that the Cesàro means of the Taylor partial sums of an analytic function in

![]() ${\mathbb {D}}$

are universal if and only if the function is itself a universal Taylor series [Reference Bayart3] (see [Reference Charpentier and Mouze15, Reference Mouze and Munnier37] for more general summation processes). Let us then introduce the following definition.

${\mathbb {D}}$

are universal if and only if the function is itself a universal Taylor series [Reference Bayart3] (see [Reference Charpentier and Mouze15, Reference Mouze and Munnier37] for more general summation processes). Let us then introduce the following definition.

Definition 3.2 (Cesàro universal Taylor series)

-

(1) We denote by

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}})$

the set of those functions

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}})$

the set of those functions

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement, and any function

$K\subset {\mathbb {C}}\setminus {\mathbb {D}}$

with connected complement, and any function

$\varphi $

continuous on K and holomorphic in its interior, there exists an increasing sequence

$\varphi $

continuous on K and holomorphic in its interior, there exists an increasing sequence

$(\lambda _n)_n$

of integers such that

$(\lambda _n)_n$

of integers such that  $$ \begin{align*} \sup_{\zeta \in K}\left\vert \frac{1}{\lambda_n+1}\sum_{j=0}^{\lambda_n}S_{j}(f)(\zeta) -\varphi (\zeta) \right\vert \to 0 \quad \text{as }n\to \infty. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \sup_{\zeta \in K}\left\vert \frac{1}{\lambda_n+1}\sum_{j=0}^{\lambda_n}S_{j}(f)(\zeta) -\varphi (\zeta) \right\vert \to 0 \quad \text{as }n\to \infty. \end{align*} $$

The elements of

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}})$

are called Cesàro universal Taylor series.

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}})$

are called Cesàro universal Taylor series. -

(2) We denote by

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

the set of those functions

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

the set of those functions

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any compact set

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

, different from

$K\subset {\mathbb {T}}$

, different from

${\mathbb {T}}$

, and any function

${\mathbb {T}}$

, and any function

$\varphi $

continuous on K, there exists an increasing sequence

$\varphi $

continuous on K, there exists an increasing sequence

$(\lambda _n)_n$

of integers such that

$(\lambda _n)_n$

of integers such that  $$ \begin{align*} \sup_{\zeta \in K}\left\vert \frac{1}{\lambda_n+1}\sum_{j=0}^{\lambda_n}S_{j}(f)(\zeta) -\varphi (\zeta) \right\vert \to 0 \quad \text{as }n\to \infty. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \sup_{\zeta \in K}\left\vert \frac{1}{\lambda_n+1}\sum_{j=0}^{\lambda_n}S_{j}(f)(\zeta) -\varphi (\zeta) \right\vert \to 0 \quad \text{as }n\to \infty. \end{align*} $$

The elements of

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

are called

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

are called

${\mathbb {T}}$

-Cesàro universal Taylor series.

${\mathbb {T}}$

-Cesàro universal Taylor series.

The last class of universal functions is that of functions with maximal cluster set along any path to

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

(by definition, a path to

${\mathbb {T}}$

(by definition, a path to

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

will always stand for a continuous function

${\mathbb {T}}$

will always stand for a continuous function

![]() $\gamma :[0,1)\to {\mathbb {D}}$

such that

$\gamma :[0,1)\to {\mathbb {D}}$

such that

![]() $\gamma (r)\to z$

for some

$\gamma (r)\to z$

for some

![]() $z\in {\mathbb {T}}$

).

$z\in {\mathbb {T}}$

).

Definition 3.3 (Functions with maximal cluster sets along every path)

We denote by

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

the set of those functions

${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

the set of those functions

![]() $f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any path to

$f \in H({\mathbb {D}})$

which satisfy the following property: for any path to

![]() ${\mathbb {T}}$

, the cluster set

${\mathbb {T}}$

, the cluster set

![]() $C_{\gamma }(f)$

of f along

$C_{\gamma }(f)$

of f along

![]() $\gamma $

is maximal, i.e., equal to

$\gamma $

is maximal, i.e., equal to

![]() ${\mathbb {C}}$

.

${\mathbb {C}}$

.

All the sets introduced above are residual in

![]() $H({\mathbb {D}})$

, so that they intersect each other. It is natural to wonder whether some nonobvious inclusions may hold. So far, here is what is known (see, e.g., [Reference Bayart3, Reference Charpentier12, Reference Charpentier and Mouze15]): for any

$H({\mathbb {D}})$

, so that they intersect each other. It is natural to wonder whether some nonobvious inclusions may hold. So far, here is what is known (see, e.g., [Reference Bayart3, Reference Charpentier12, Reference Charpentier and Mouze15]): for any

![]() $\varrho =(r_n)_n$

,

$\varrho =(r_n)_n$

,

-

•

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}})={\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}}) \subsetneq {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}}) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

;

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}})={\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}}) \subsetneq {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}}) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

; -

•

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho ) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}}) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

;

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho ) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}}) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

; -

•

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

and

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

and

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\setminus {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}}) \neq \emptyset $

.

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\setminus {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}}) \neq \emptyset $

.

Note that the inclusions

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}}) \subset {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

and

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}}) \subset {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

and

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho ) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}}) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

are either trivial or obvious. Moreover, that

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho ) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}}) \subset {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

are either trivial or obvious. Moreover, that

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

is a consequence of the existence of universal Taylor series that are Abel summable at some boundary points [Reference Costakis20]. The assertion

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

is a consequence of the existence of universal Taylor series that are Abel summable at some boundary points [Reference Costakis20]. The assertion

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\setminus {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

was observed in [Reference Charpentier12] using that functions in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\setminus {\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

was observed in [Reference Charpentier12] using that functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

possess Ostrowski gaps, whereas some functions in

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}})$

possess Ostrowski gaps, whereas some functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

may not have Ostrowski gaps. We mention that functions in

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

may not have Ostrowski gaps. We mention that functions in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

may not have Ostrowski gaps in general [Reference Charpentier and Mouze15]. The aim of this section is to contribute in completing the description of the relationships between these classes. Precisely, we will prove the following.

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

may not have Ostrowski gaps in general [Reference Charpentier and Mouze15]. The aim of this section is to contribute in completing the description of the relationships between these classes. Precisely, we will prove the following.

Proposition 3.1 For any

![]() $\varrho =(r_n)_n$

, we have:

$\varrho =(r_n)_n$

, we have:

-

(1)

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})\neq \emptyset $

;

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})\neq \emptyset $

; -

(2)

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\neq \emptyset $

;

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )\neq \emptyset $

; -

(3)

${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

.

${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\neq \emptyset $

.

In particular, the sets

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

and

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

and

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

are incomparable.

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

are incomparable.

In passing, we can deduce (from (a) and

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\subset {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

) that

${\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}})\subset {\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})$

) that

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})\neq \emptyset $

. However, it is still an open question whether

${\mathcal {U}}_C({\mathbb {D}})\setminus {\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})\neq \emptyset $

. However, it is still an open question whether

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

is included in

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

is included in

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

or not (i.e., whether

${\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

or not (i.e., whether

![]() ${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})={\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

or not).

${\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})={\mathcal {U}}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

or not).

Proof of Proposition 3.1

We first prove (a). Let

![]() $(R_n)_n\subset [0,1)$

be such that

$(R_n)_n\subset [0,1)$

be such that

![]() $0<R_n<r_n<R_{n+1}<r_{n+1}<1$

,

$0<R_n<r_n<R_{n+1}<r_{n+1}<1$

,

![]() $n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

. Let us define, for every

$n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

. Let us define, for every

![]() $0<r<1$

and

$0<r<1$

and

![]() $k\geq 0$

,

$k\geq 0$

,

$$ \begin{align} H_k(r)=\sum_{j\geq k}h_j(r)\quad \mbox{ where }\quad h_j(r):=\sum_{i=j}^{+\infty}2ir^i. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} H_k(r)=\sum_{j\geq k}h_j(r)\quad \mbox{ where }\quad h_j(r):=\sum_{i=j}^{+\infty}2ir^i. \end{align} $$

Observe that

![]() $H_k(r)\rightarrow 0$

as k tends to infinity. We choose

$H_k(r)\rightarrow 0$

as k tends to infinity. We choose

![]() $u_1>0$

such that

$u_1>0$

such that

$$ \begin{align*}\max\left(H_{u_{1}}(r_{1}),\frac{(r_1/R_{2})^{u_1}}{1-r_1/R_{2}}\right)\leq \varepsilon_1.\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\max\left(H_{u_{1}}(r_{1}),\frac{(r_1/R_{2})^{u_1}}{1-r_1/R_{2}}\right)\leq \varepsilon_1.\end{align*} $$

By Mergelyan’s theorem, we find

![]() $P_1=\sum \limits _{i\geq u_1}a_{i,1}z^i$

so that

$P_1=\sum \limits _{i\geq u_1}a_{i,1}z^i$

so that

Let us build by induction sequences

![]() $(P_n)_n$

and

$(P_n)_n$

and

![]() $(Q_n)_n$

of polynomials and an increasing sequence

$(Q_n)_n$

of polynomials and an increasing sequence

![]() $(u_n)_n$

of integers as follows. Let

$(u_n)_n$

of integers as follows. Let

![]() $Q_0=0$

and suppose that

$Q_0=0$

and suppose that

![]() $P_1,\dots ,P_{n-1}$

,

$P_1,\dots ,P_{n-1}$

,

![]() $u_1,\dots ,u_{n-1}$

, and

$u_1,\dots ,u_{n-1}$

, and

![]() $Q_0,\dots ,Q_{n-2}$

have been chosen for

$Q_0,\dots ,Q_{n-2}$

have been chosen for

![]() $n\geq 2$

. We shall write these polynomials under the following form:

$n\geq 2$

. We shall write these polynomials under the following form:

$$ \begin{align*}\mbox{for } k=2,\dots, n-2,\hspace{6pt} P_k=\sum_{i=u_k}^{u_{k+1}-1}a_{i,k}z^i,\hspace{6pt} Q_{k}=\sum_{i=u_{k}}^{u_{k+1}-1}b_{i,k}z^i,\hspace{6pt} \mbox{ with }u_k\geq\deg(P_{k-1})+1,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}\mbox{for } k=2,\dots, n-2,\hspace{6pt} P_k=\sum_{i=u_k}^{u_{k+1}-1}a_{i,k}z^i,\hspace{6pt} Q_{k}=\sum_{i=u_{k}}^{u_{k+1}-1}b_{i,k}z^i,\hspace{6pt} \mbox{ with }u_k\geq\deg(P_{k-1})+1,\end{align*} $$

and

$$ \begin{align*}P_{n-1}=\sum_{i=u_{n-1}}^{\deg(P_{n-1})}a_{i,n-1}z^i,\mbox{ with }u_{n-1}\geq\deg(P_{n-2})+1,\end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*}P_{n-1}=\sum_{i=u_{n-1}}^{\deg(P_{n-1})}a_{i,n-1}z^i,\mbox{ with }u_{n-1}\geq\deg(P_{n-2})+1,\end{align*} $$

where the coefficients

![]() $a_{i,j}$

and

$a_{i,j}$

and

![]() $b_{i,j}$

will satisfy suitable conditions that will be specified in the induction. We are going to construct

$b_{i,j}$

will satisfy suitable conditions that will be specified in the induction. We are going to construct

![]() $u_n$

,

$u_n$

,

![]() $Q_{n-1}$

, and

$Q_{n-1}$

, and

![]() $P_n$

in this order. First, choose

$P_n$

in this order. First, choose

![]() $u_n\geq 1+ \deg (P_{n-1})$

satisfying

$u_n\geq 1+ \deg (P_{n-1})$

satisfying

-

(1)

$\max \left (H_{u_{n}}(r_{n}), \frac {(r_n/R_{n+1})^{u_n}}{1-r_n/R_{n+1}}\right )\leq \varepsilon _n$

.

$\max \left (H_{u_{n}}(r_{n}), \frac {(r_n/R_{n+1})^{u_n}}{1-r_n/R_{n+1}}\right )\leq \varepsilon _n$

.

Set

![]() $a_{i,n-1}=0$

for

$a_{i,n-1}=0$

for

![]() $i=\deg (P_{n-1})+1,\dots ,u_n-1$

, which implies that

$i=\deg (P_{n-1})+1,\dots ,u_n-1$

, which implies that

![]() $P_{n-1}=\sum \limits _{i=u_{n-1}}^{u_n-1}a_{i,n-1}z^i.$

Let us consider

$P_{n-1}=\sum \limits _{i=u_{n-1}}^{u_n-1}a_{i,n-1}z^i.$

Let us consider

![]() $w_{n-2}(z)=\sum \limits _{j=1}^{n-2}(P_j+Q_j)(z)$

,

$w_{n-2}(z)=\sum \limits _{j=1}^{n-2}(P_j+Q_j)(z)$

,

![]() $z\in {\mathbb {C}}$

. Then we define

$z\in {\mathbb {C}}$

. Then we define

![]() $Q_{n-1}=\sum \limits _{i= u_{n-1}}^{u_n-1}b_{i,n-1}z^i$

, where the coefficients

$Q_{n-1}=\sum \limits _{i= u_{n-1}}^{u_n-1}b_{i,n-1}z^i$

, where the coefficients

![]() $b_{i,n-1}$

for

$b_{i,n-1}$

for

![]() $u_{n-1}\leq i\leq u_n-1$

are built by induction as follows. We first set

$u_{n-1}\leq i\leq u_n-1$

are built by induction as follows. We first set

$$ \begin{align*} b_{u_{n-1},n-1}:=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} 0, & \text{if } \vert \sum\limits_{l=1}^{u_{n-1}}S_l(w_{n-2})(1) + a_{u_{n-1},n-1}\vert \geq u_{n-1},\\ 2u_{n-1}, & \text{otherwise}. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} b_{u_{n-1},n-1}:=\left\{\begin{array}{ll} 0, & \text{if } \vert \sum\limits_{l=1}^{u_{n-1}}S_l(w_{n-2})(1) + a_{u_{n-1},n-1}\vert \geq u_{n-1},\\ 2u_{n-1}, & \text{otherwise}. \end{array} \right. \end{align*} $$

Then, once

![]() $b_{u_{n-1},n-1},b_{u_{n-1}+1,n-1},\ldots , b_{k-1,n-1}$

have been built for some

$b_{u_{n-1},n-1},b_{u_{n-1}+1,n-1},\ldots , b_{k-1,n-1}$

have been built for some

![]() $u_{n-1}+1\leq k\leq u_n-1$

, we set:

$u_{n-1}+1\leq k\leq u_n-1$

, we set:

-

•

$b_{k,n-1}=0$

if we have

$b_{k,n-1}=0$

if we have

$\left \vert \sum \limits _{l=1}^{k}S_l(w_{n-2})(1) + \sum \limits _{l=u_{n-1}}^{k-1}\sum \limits _{i=u_{n-1}}^{l}(a_{i,n-1}+b_{i,n-1}) + \sum \limits _{i=u_{n-1}}^{k-1}(a_{i,n-1}+b_{i,n-1}) + a_{k,n-1}\right \vert \geq k,$

$\left \vert \sum \limits _{l=1}^{k}S_l(w_{n-2})(1) + \sum \limits _{l=u_{n-1}}^{k-1}\sum \limits _{i=u_{n-1}}^{l}(a_{i,n-1}+b_{i,n-1}) + \sum \limits _{i=u_{n-1}}^{k-1}(a_{i,n-1}+b_{i,n-1}) + a_{k,n-1}\right \vert \geq k,$

-

•

$b_{k,n-1}=2k$

otherwise.

$b_{k,n-1}=2k$

otherwise.

Doing so, we obtain for all

![]() $n\geq 2$

and for all

$n\geq 2$

and for all

![]() $k=u_{n-1},\dots ,u_n-1$

,

$k=u_{n-1},\dots ,u_n-1$

,

-

(2)

$\vert \sum _{l=1}^{k}S_l(\sum _{j=1}^{n-1}(P_j+Q_j))(1) \vert \geq k$

;

$\vert \sum _{l=1}^{k}S_l(\sum _{j=1}^{n-1}(P_j+Q_j))(1) \vert \geq k$

; -

(3)

$|b_{k,n-1}|\leq 2k$

.

$|b_{k,n-1}|\leq 2k$

.

Then apply Mergelyan’s theorem to get

![]() $P_n=\sum \limits _{i\geq u_n}a_{i,n}z^i$

so that the following conditions hold:

$P_n=\sum \limits _{i\geq u_n}a_{i,n}z^i$

so that the following conditions hold:

-

(4)

$\sup _{|z|\leq R_n} | P_n(z) | \leq \varepsilon _n$

;

$\sup _{|z|\leq R_n} | P_n(z) | \leq \varepsilon _n$

; -

(5)

$\sup _{z\in K_{\alpha (n)}}|P_n(r_nz)-\left (\varphi _{\beta (n)}(z)-\sum _{0\leq j\leq n-1}(P_j+Q_j)(r_nz)\right )|\leq \varepsilon _n$

.

$\sup _{z\in K_{\alpha (n)}}|P_n(r_nz)-\left (\varphi _{\beta (n)}(z)-\sum _{0\leq j\leq n-1}(P_j+Q_j)(r_nz)\right )|\leq \varepsilon _n$

.

Finally, we set

![]() $f=\sum \limits _{n\geq 1}(P_n+Q_n)$

and get from (3) and (4) that

$f=\sum \limits _{n\geq 1}(P_n+Q_n)$

and get from (3) and (4) that

![]() $f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

. Moreover, it is clear from (2) that

$f\in H({\mathbb {D}})$

. Moreover, it is clear from (2) that

![]() $|\sum \limits _{l=1}^{k}S_l(f)(1)|\geq k$

, for all

$|\sum \limits _{l=1}^{k}S_l(f)(1)|\geq k$

, for all

![]() $k\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, and therefore

$k\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, and therefore

![]() $f\not \in {\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

. The proof will be completed once we have proved that

$f\not \in {\mathcal {U}}_{Ces}({\mathbb {D}},{\mathbb {T}})$

. The proof will be completed once we have proved that

![]() $f\in {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

. To do this, we will use the equality (3.1). Let us fix

$f\in {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

. To do this, we will use the equality (3.1). Let us fix

![]() $n,m\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, and let

$n,m\in {\mathbb {N}}$

, and let

![]() $(n_l)_l\subset {\mathbb {N}}$

be such that for any

$(n_l)_l\subset {\mathbb {N}}$

be such that for any

![]() $l\in {\mathbb {N}}$

,

$l\in {\mathbb {N}}$

,

![]() $\alpha (n_l)=n$

and

$\alpha (n_l)=n$

and

![]() $\beta (n_l)=m$

. By (5), we have, for any

$\beta (n_l)=m$

. By (5), we have, for any

![]() $\zeta \in K_n$

,

$\zeta \in K_n$

,

$$ \begin{align*} \left|f(r_{n_l}\zeta)-\varphi_m(\zeta)\right| \leq \varepsilon_{n_l} + \left|Q_{n_l}(r_{n_l}\zeta)\right| + \left|\sum _{j\geq n_l+1} \left(P_j(r_{n_l}\zeta)+Q_j(r_{n_l}\zeta)\right)\right|\!. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \left|f(r_{n_l}\zeta)-\varphi_m(\zeta)\right| \leq \varepsilon_{n_l} + \left|Q_{n_l}(r_{n_l}\zeta)\right| + \left|\sum _{j\geq n_l+1} \left(P_j(r_{n_l}\zeta)+Q_j(r_{n_l}\zeta)\right)\right|\!. \end{align*} $$

Moreover, it follows from (3), (3.1), and (1) that for any

![]() $\zeta \in K_{n}$

,

$\zeta \in K_{n}$

,

Now, let us observe by (4) and Cauchy’s inequalities that we have

![]() $\left |a_{i,j}\right |\leq \varepsilon _{j}R_{j}^{-i}$

for any

$\left |a_{i,j}\right |\leq \varepsilon _{j}R_{j}^{-i}$

for any

![]() $j\geq 1$

and any

$j\geq 1$

and any

![]() $u_j \leq i \leq u_{j+1}-1$

, whence by (1), (3.1), and (3),

$u_j \leq i \leq u_{j+1}-1$

, whence by (1), (3.1), and (3),

$$ \begin{align*} \left|\sum_{j\geq n_l+1} \left(P_j(r_{n_l}\zeta)+Q_j(r_{n_l}\zeta)\right)\right| & \leq \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\sum_{i\geq u_{j}}\varepsilon_{j}\left(\frac{r_{n_l}}{R_{j}}\right)^i+ \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\sum_{i\geq u_{j}}2ir_{n_l}^i \\& \leq \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\varepsilon_{j}\left(\frac{r_{n_l}}{R_{n_l+1}}\right)^{u_{n_l}}\frac{1}{1-r_{n_l}/R_{n_l+1}}+ \sum_{j\geq n_l+1} h_{u_j}(r_{n_l}) \\&\leq \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\varepsilon_{j}+H_{u_{n_l}}(r_{n_l}) \\& \leq \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\varepsilon_{j} + \varepsilon_{n_l}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \left|\sum_{j\geq n_l+1} \left(P_j(r_{n_l}\zeta)+Q_j(r_{n_l}\zeta)\right)\right| & \leq \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\sum_{i\geq u_{j}}\varepsilon_{j}\left(\frac{r_{n_l}}{R_{j}}\right)^i+ \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\sum_{i\geq u_{j}}2ir_{n_l}^i \\& \leq \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\varepsilon_{j}\left(\frac{r_{n_l}}{R_{n_l+1}}\right)^{u_{n_l}}\frac{1}{1-r_{n_l}/R_{n_l+1}}+ \sum_{j\geq n_l+1} h_{u_j}(r_{n_l}) \\&\leq \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\varepsilon_{j}+H_{u_{n_l}}(r_{n_l}) \\& \leq \sum_{j\geq n_l+1}\varepsilon_{j} + \varepsilon_{n_l}. \end{align*} $$

Altogether we get

and thus

![]() $f\in {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

.

$f\in {\mathcal {U}}_A({\mathbb {D}},\varrho )$

.

Let us prove (b). Let

![]() $\varrho '=\left (r_n'\right )_n\subset [0,1)$

be an increasing sequence such that

$\varrho '=\left (r_n'\right )_n\subset [0,1)$

be an increasing sequence such that

![]() $r_n < r^{\prime }_n < r_{n+1}$

,

$r_n < r^{\prime }_n < r_{n+1}$

,

![]() $n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

. Using Runge’s theorem, we build by induction a sequence of polynomials

$n\in {\mathbb {N}}$

. Using Runge’s theorem, we build by induction a sequence of polynomials

![]() $P_n$

such that:

$P_n$

such that:

-

(1)

$\sup _{|z|\leq r^{\prime }_{n-1}}\vert P_n(z)\vert \leq \varepsilon _n$

;