In many Western democracies—including Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom—we have witnessed a decline in voter turnout, which is most pronounced among the younger generations (Aarts and Wessels, Reference Aarts, Wessels and Thomassen2005; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil and Nevitte2004; Smets, Reference Smets2012). While the downward trend in turnout and widening age gap has varied in time and scale across countries, it is nonetheless a common pattern for liberal democracies (Hooghe and Kern, Reference Hooghe and Kern2017; Smets, Reference Smets2012), and has thus spurred discussion among academics and practitioners to investigate factors that could stop or even revert this decline in electoral participation, and more specifically among youth. In Canada, various measures have been considered or implemented to foster democratic values, boost motivation to participate and ultimately make voting easier for young people, such as civic education programs in schools (Mahéo, Reference Mahéo2018), voter preregistration for the 16- and 17-year-olds (Canada, 2017), or lowering the voting age to 16 (Canada, 2016).

Reform of the voting age has been implemented, to varying degrees, in only a few European and South American countries or regions, such as Austria, Scotland, Norway, Estonia, Germany, Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Ecuador, Malta, and Nicaragua. But given the lack of clear evidence on the positive effects of such a reform, many countries like Canada and the UK are still weighing the value of this institutional change (Canada, 2016; Eichhorn and Mycock, Reference Eichhorn and Mycock2015; United Kingdom, 2003). Proponents of this reform argue that allowing the 16- and 17-year-olds to vote for the first time while they are still in school and living at home with their parents could have long-term positive effects on turnout (Bergh, Reference Bergh2013; Franklin, Reference Franklin2004; Zeglovits, Reference Zeglovits2013). However, critics point out that underage youth are not politically “mature” enough to take part in elections, and consequently, the quality of electoral participation and political representation could be hindered (Chan and Clayton, Reference Chan and Clayton2006). While the debate between different theoretical perspectives and normative arguments continues, we still need more and clearer empirical evidence to inform this debate and guide policy makers. In fact, the few studies that have investigated the impact of a change in the voting age on political engagement and political competence present mixed—or even contradictory—evidence (Zeglovits, Reference Zeglovits2013).

We propose to contribute to the examination of the implications of changing the voting age, by extending the empirical literature to a new context: Canada. This country has registered an important decline in turnout and a widening age gap in turnout, more so than other countries (Smets, Reference Smets2012), which has prompted reflection on measures to address this democratic challenge. This study is particularly timely, as the electoral management body of Canada, as well as several Canadian provinces and municipalities, are currently considering changing the voting age (British Columbia, 2018; Harris, Reference Harris2018; Hennig, Reference Hennig2018; Potkins, Reference Potkins2018).

Furthermore, we test empirically the validity of an argument of the critics—youth's lack of political resources—and one argument of the proponents—the supportive influence of socialization agents. Using a post-electoral opinion survey conducted in Quebec in 2018, with a general population sample and an additional sample of underage youth, we examine whether 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds are substantively different or relatively similar in terms of their political engagement and competence. Additionally, we assess whether socialization agents (parents, professors and peers) can be particularly supportive of the political engagement of 16- to 17-year-olds (Eichhorn, Reference Eichhorn2018; Franklin, Reference Franklin2004; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Johann and Kritzinger2012). A better understanding of the (potential) differences in the socialization and engagement of underage and adult youth can inform the public debate and decisions of policy makers with regards to reform of the voting age.

This study first presents the developmental approach and the literature examining the potential impact of lowering the voting age on turnout and engagement, as well as the research on political socialization and the social context of youth engagement. After giving details on the survey and our variables of interest, we provide a description of the comparability of participation intentions, political engagement and social network influences among 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds. The study finally turns to multivariate analyses examining the individual and social factors of youth engagement.

Considerations about Turnout and Age: An Argument in Favor of Lowering the Voting Age to 16

The developmental theory of turnout highlights the importance of the ‘starting’ point of turnout—whether citizens vote or not in their first eligible election—and the ensuing voting habit—whether citizens then adopt a durable path of voting or nonvoting (Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002). The general observation is that, more and more, young people ‘start’ their democratic life as nonvoters and risk becoming habitual nonvoters. In fact, there is ample evidence that in the past decades, in many Western democracies, youth have been voting at lower rates (Bhatti and Hansen, Reference Bhatti and Hansen2012a; Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil and Nevitte2004; Blais and Rubenson, Reference Blais and Rubenson2013; Fieldhouse et al., Reference Fieldhouse, Tranmer and Russell2007; Gallego, Reference Gallego2009; Rubenson et al., Reference Rubenson, Blais, Fournier, Gidengil and Nevitte2004).

One assumption put forward by Franklin (Reference Franklin2004, Reference Franklin, Eichhorn and Bergh2020) is that the voting age of 18 may be disadvantaging youth in how they learn voting behaviour. Based on a life-cycle perspective, the idea is that young adults over 18 are in a stage of life where they are busy with other life considerations related to their studies and work, while also experiencing higher residential mobility, and are thus less interested or available to be involved in politics (Highton and Wolfinger, Reference Highton and Wolfinger2001; Pacheco and Plutzer, Reference Pacheco and Plutzer2007). Franklin's argument is that offering the possibility to vote to young people when they are still at home and in school could lead to increased turnout levels. The main idea is that living at home and being in school would allow youth to vote for the first time in a supportive social environment—one that may sustain their political interest and help them gain the necessary resources to vote. The general expectation is that lowering the voting age to 16 would offer better social conditions for youth to vote in their first election, leading them to become habitual voters, which would result in a long-term increase in voter turnout.

But what does the empirical literature say about the comparability of turnout rates of the 16- to 17-year-olds versus older youth? This literature is limited given the few cases in which 16- to 17-year-olds have been able to vote. Austria is the only Western country that has lowered the voting age to 16 for all elections, since 2007.Footnote 1 Alternatively, in Norway, 16- and 17-year-olds were allowed to vote in ‘trial elections’ in 20 municipalities in 2011; in Germany, since the 1990s, a few states have allowed 16- to 17-year-olds to vote in municipal or state elections; and in Scotland, 16- and 17-year-olds were allowed to vote in the 2014 independence referendum. In all these cases, the evidence is consistent: when offered the possibility to vote, 16- and 17-year-olds turn out at rates as high or higher than 18- to 20-year-olds (Aichholzer and Kritzinger, Reference Aichholzer, Kritzinger, Eichhorn and Bergh2020; Bergh, Reference Bergh2013; Eichhorn, Reference Eichhorn2018; Leininger and Faas, Reference Leininger, Faas, Eichhorn and Bergh2020; Odegard et al., Reference Odegard, Bergh, Saglie, Eichhorn and Bergh2020; Zeglovits, Reference Zeglovits2013). But most importantly, part of Franklin's (Reference Franklin2004, Reference Franklin, Eichhorn and Bergh2020) argument was confirmed in these cases, where turnout was immediately higher among the 16- and 17-year-old first time voters, compared to that of older first time voters who were 18- to 20-years-old (Bergh, Reference Bergh2013; Eichhorn, Reference Eichhorn2018; Zeglovits and Aichholzer, Reference Zeglovits and Aichholzer2014).

Recent evidence also tends to support the expectation of durable effects of the reform on turnout levels. While Wagner and colleagues (Reference Wagner, Johann and Kritzinger2012) reported that Austrians aged 16 and 17 had lower intentions to participate in the less salient 2009 EU elections (compared to 18- to 21-year-olds), Bronner and Ifkovits (Reference Bronner and Ifkovits2019) instead document higher probabilities of voting among 16-year-olds in the more salient 2013 general election, compared to adult youth. They further show that, in addition to higher starting levels of turnout, underage youth are as subject to the habituation effect as older first-time voters, which provides a durable and positive effect of the reform of the voting age on turnout. In Scotland, Eichhorn (Reference Eichhorn2018) also documents increased intentions to participate in UK general elections, as well as in non-electoral forms of participation. And indeed, if we look at the latter form of participation—for which there is no age limit to actual participation—we find that underage youth display equal or higher levels of motivation, as they are as active or more active than adult youth and the rest of the population in a variety of ways (Hart and Atkins, Reference Hart and Atkins2011; Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2007).

However, generalizations from the Scottish, Austrian and Norwegian cases about youth's willingness to take part in elections may be limited. In these three cases, the increase in turnout among youth may be related to the civic programs and campaigns implemented before the reform, the novelty effect of the institutional reform, or the strong political debates in the case of Scotland's referendum (Bergh, Reference Bergh2013; Eichhorn, Reference Eichhorn2018; Zeglovits, Reference Zeglovits2013).

Considerations about Political Resources and Age: An Argument Against Lowering the Voting Age to 16

One of the arguments presented to oppose a lowering of the voting age is that young people are not “mature” enough to vote (Chan and Clayton, Reference Chan and Clayton2006). The concern is that young people lack political sophistication and the necessary resources to take part in elections. If young people are not knowledgeable, nor interested in politics, they are less likely to cast an informed vote, one that adequately represents their interests. While including more voters in electoral democracy can be good for the representation of more and various interests, and especially the needs of under-represented groups such as youth, it can be detrimental to representative democracy if individuals lack the ability to link their interests to political options through their vote.

There is no clear definition of political “maturity” (Chan and Clayton, Reference Chan and Clayton2006), but the political behaviour literature focuses on political abilities such as political interest, knowledge, efficacy and consistency of attitudes as important factors of political participation. The Civic Voluntarism Model focuses on the psychological and social resources that explain political participation (Verba et al., Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995). In their model, Verba and colleagues show that individuals need capabilities and motivation to participate, in addition to social networks that mobilize individuals into political action. They identify political interest and knowledge as important factors of political action, and several studies find strong empirical evidence linking knowledge and interest to various political behaviours, such as voting and information searching (Delli Carpini and Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Schlozman et al., Reference Schlozman, Verba and Brady2010; Shah et al., Reference Shah, Kwak and Lance Holbert2001). Feelings of political efficacy (that is, the assessment of one's ability to understand and influence politics) can also drive political participation (Beaumont, Reference Beaumont, Sherrod, Torney-Purta and Flanagan2010; Zukin et al., Reference Zukin, Keeter, Andoline, Jenkins and Delli Carpini2006). A final criterion of voter preparedness is the degree to which attitudes are logically organized (Converse, Reference Converse and Apter1964; Luskin, Reference Luskin1987). If individuals can organize in a coherent manner their positions on issues, they are more likely to support parties or policies that are compatible with their preferences.

While these factors are generally important for political participation, in the context of the debate over the lowering of the voting age, we may wonder whether underage youth and young adults have different levels of political resources. Cognitive resources—such as political knowledge—tend to increase with age (Delli Carpini and Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Wolfinger and Rosenstone, Reference Wolfinger and Rosenstone1980). But the literature on political development shows that there is an important and rapid development in political interest, knowledge and skills during adolescence that plateaus after the age of 16 (Hart and Atkins, Reference Hart and Atkins2011; Highton, Reference Highton2009; Jennings and Niemi, Reference Jennings and Niemi1981; Prior, Reference Prior2010). As political sophistication and skills are rather set by the age of 16, the political differences within youth should be minimal after this age. However, there are indications that there may still be some changes in individuals’ political development up until their mid-20s (Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Stoker and Bowers2009; Neundorf et al., Reference Neundorf, Smets and Garcia-Albacete2013).

The literature on the political capacities of youth presents mixed—and even contradictory—findings on the comparability of 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds. On one hand, research from the United States and Austria shows that 16- to 17-year-olds are as well-equipped as other age groups to take part in politics (Hart and Atkins, Reference Hart and Atkins2011; Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Johann and Kritzinger2012). Also, when Wagner and colleagues (Reference Wagner, Johann and Kritzinger2012) compare several youth groups across each other, and to adults over 31years of age, they find that underage youth are not less interested, a bit less knowledgeable (but not compared to all age groups), and as motivated or more motivated to take part in non-electoral forms of participation.

On the other hand, evidence from the United Kingdom and Norway presents a different picture, one in which underage youth are less politically resourceful. Chan and Clayton (Reference Chan and Clayton2006) find real differences, where youth have lower levels of interest and knowledge compared to adults, as well as less consistency in their political attitudes. But these differences could easily be explained by the fact that one group is enfranchised, while the other is not. Indeed, it is likely that having the right to vote has a determining effect on one's interest in elections, and had 16- to 17-year-olds been given the right to vote, they could have had a clearer incentive to be interested in elections. However, Bergh (Reference Bergh2013) also documents differences in the levels of political interest, efficacy and attitudinal consistency of 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds, where the youngest Norwegians score lower than the oldest age group, and finds that temporary enfranchisement during ‘trial elections’ did not close these gaps in political competence. However, a mere ‘trial’ of enfranchisement might not be a meaningful and durable incentive for underage youth to engage in the electoral process.

Overall, research on political development tends to indicate that the ages of 16 and 17 may represent a particularly timely stage of life to experience voting for the first time, leading to an increase in the number of votes cast. However, there is contradictory evidence on the comparability of political motivation and resources of 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds. Thus, we formulate general research questions about the differences in political engagement and resources between these two groups:

RQ1: Are there differences in the motivation for politics involvement between underage and adult youth?

RQ2: Are there differences in the political abilities of 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds for effective involvement in politics?

If there are no differences between these two age groups regarding their political motivation and abilities, then the critics’ case against reform of the voting age becomes weaker. However, if there are differences in resources between these youth groups, or if older youth prove to be more politically resourceful than their younger counterparts, this alone is not sufficient support for the critics' argument. Indeed, adult youth may have greater ability and motivation to participate simply because they are enfranchised.

The Importance of the Social Context and the Role of Socialization Agents

Beyond an individual's psychological engagement with politics, his or her social context also matters for political participation. The Civic Voluntarism Model and socialization theory demonstrate that a variety of social actors influence the political development and participation of individuals: family (and more specifically parents), peers, schools and teachers (Beck and Jennings, Reference Beck and Kent Jennings1982; Bekkers, Reference Bekkers2005; Gallego and Oberski, Reference Gallego and Oberski2012; Nickerson, Reference Nickerson2008; Nie et al., Reference Nie, Junn and Stehlik-Barry1996; Scheufele et al., Reference Scheufele, Nisbet, Brossard and Nisbet2004). Social resources may be particularly helpful for youth who may have lower levels of individual resources (be it political interest, knowledge or skills) (McClurg, Reference McClurg2003; Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002).

The mechanisms through which social networks affect political participation are twofold. First, through political discussion, social networks expose individuals to a range of factors including: politically relevant information, desirability and norms of participation, awareness of certain political issues or politics in general; and information about opportunities of engagement or how to participate (McClurg, Reference McClurg2003; Teorell, Reference Teorell2003; Zuckerman, Reference Zuckerman2005). Second, through social recruitment or mobilization, individuals are directly exposed to opportunities for participation (Teorell, Reference Teorell2003).

The family is the primary social environment for children and an important agent of political socialization (Beck and Jennings, Reference Beck and Kent Jennings1982). The transmission model posits that parents transfer directly and indirectly their societal beliefs, political attitudes and behaviours to their children. But the impact of parents on their children's lives declines over time, notably when children leave the family home (Highton and Wolfinger, Reference Highton and Wolfinger2001). At that time, peers may have relatively more influence on individuals’ political engagement and voting behaviour (Bhatti and Hansen, Reference Bhatti and Hansen2012b). However, youth's peers may be just as politically inexperienced and may be nonvoters, thus limiting this network's potential benefits for engagement (Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002). Schools also play an important part in youth's political learning and preparation for political participation (Beck and Jennings, Reference Beck and Kent Jennings1982). In fact, there is evidence that service learning programs in school, open class discussions, student governments, and civics courses can help develop a sense of civic duty, civic and communication skills, knowledge about politics and institutions among students, and can provide meaningful ways to promote democratic citizenship and to equip future citizens to be active in society as they age (Campbell, Reference Campbell2008; Galston, Reference Galston2001; Mahéo, Reference Mahéo2018; Torney-Purta, Reference Torney-Purta1997; Torney-Purta and Richardson, Reference Torney-Purta, Richardson, Patrick and Hamot2003; Torney-Purta et al., Reference Torney-Purta, Amadeo, Richardson, McBride and Sherraden2007).

The argument developed by Franklin (Reference Franklin2004) for lowering the voting age to 16 is that youth would experience their first vote in a more supportive environment. In fact, youth around the ages of 16 and 17 are more likely to live at home and to attend school than youth aged 18 or older (Quebec 2016, 2018), which would lead them to reap increased benefits from their socialization environment at the time of casting their first vote (Highton and Wolfinger, Reference Highton and Wolfinger2001). Indeed, Zeglovits and Zandonella (Reference Zeglovits and Zandonella2013) show that both schools and parental environments are important factors that foster political interest among 16- to 17-year-olds. But while in the Austrian and Scottish contexts schools play an important role in the political development of underage youth—and more so than parents—(Eichhorn, Reference Eichhorn2018; Schwarzer and Zeglovits, Reference Schwarzer, Zeglovits and Abendschön2013; Zeglovits and Zandonella, Reference Zeglovits and Zandonella2013), we still lack comparable evidence on these social networks’ influences for 18- to 20-year-olds, and comparable evidence for other types of network influences that are important for youth, such as peers.

Additionally, recent studies on the life cycle explanation of voter turnout lead us to believe that differences between the lives of 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds may not be as stark as they used to be. In fact, the transition to adulthood has been delayed and it now takes more time for youth to attain several markers of adult status, such as living with a partner or buying a house (Flanagan et al., Reference Flanagan, Finlay, Gallay and Kim2011). These life events are associated with more opportunities to be interested and mobilized in politics, which would explain why today's youth vote at lower rates than previous generations (Smets, Reference Smets2012, Reference Smets2016). With later maturation, it is now more likely that youth under 20 have not experienced these transitional moments, and 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds would thus be on par in terms of opportunities to acquire political resources and be mobilized through their life context.

Given the consistent evidence on the importance of socialization agents, political discussion and mobilization for engagement, and more specifically for youth engagement, we expect that:

H1: Frequency of political discussion and exposure to political information and education activities will be positively related to the political competence and engagement of youth.

In the contemporary context, in which youth do not consistently experience changes in their social life and assume new adult roles around the age of 18, we wonder whether some of the social contexts in youth's lives have varying effects for underage and adult youth. We thus formulate a last open research question:

RQ3: Do political discussions with one's network and activities at school have a distinct impact on the political competence and engagement of underage youth, compared to adult youth?

Methods

Data

Our public opinion survey was conducted immediately after the 2018 Quebec provincial election. The data were collected online by the polling firm Léger via a questionnaire administered to their web panel. A total of 3,072 individuals responded to the survey, of which 251 were 16–17 years old and 212 were 18–20 years of age. The inclusion of a subsample of underage youth is rare in political opinion surveys. It enables us to examine in-depth the political profile of soon-to-be voters (16- to 17-year-olds) and first-time voters in this 2018 election (18- to 20-year-olds). It further enables us to directly compare underage and adult youth, using the same questions, in the same political context. This comparison is not perfect, as older youth have the right to vote, while the younger ones do not, and thus, in our interpretation of inter-age group comparisons, we keep in mind that analyses also account for the effect of being enfranchised. Our comparative results are nonetheless more reliable than those produced by previous studies that used different types of surveys and different questions to compare engagement and participation among various age groups (for example, Hart and Atkins, Reference Hart and Atkins2011; Zeglovits and Zandonella, Reference Zeglovits and Zandonella2013).

Variables of Interest

We limit our analysis to youth aged 16–20 years old, as we compare youth just under 18 to those 18 and above on a variety of political indicators. Hence, in all analyses a variable for ageFootnote 2 is included and is sometimes used in interactions.

Given that youth under 18 do not have the right to vote in Canada, we cannot compare the 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds on actual voting behaviour. Instead we compare them on intentions to participate in elections in general and in a referendum if given the opportunity.

Luskin (Reference Luskin1987) discusses various measures of political sophistication or resourcefulness, and concludes that political knowledge is the most objective measure. To measure factual knowledge, respondents were asked seven questions about political figures and institutions. We thus use a knowledge scale in the analyses. We further use a measure of internal efficacy (that is, whether respondents feel they can understand politics) and a self-reported measure of respondent level of interest in politics, as indicators of voter preparedness. Finally, we look at the consistency of political attitudes on two dimensions: state intervention and immigration.

We also examine the influence of social networks on individual political resources and participation intentions. First, we use measures of the frequency of discussions about the election with various interlocutors in a respondent's social network: parents, friends, professors and other family members. We also consider whether youth attended a political debate at their school or university. Finally, we examine campaign activities that can impact political engagement and participation: having been in contact with a politician and having watched the political leaders’ debate.

We further include in the analyses control variables that are known to affect political engagement and participation: gender and visible minority status, as well as respondents’ parents’ education to control for socio-economic status.Footnote 3

Analytical Strategy

We first present bivariate analyses that explore potential differences between the two youth groups on attitudinal and behavioural measures. In a second step, we test these intergroup differences in a multivariate setting. This allows us to confirm the presence (or absence) of significant differences between the two age groups (while controlling for sociodemographic determinants), but also to test the hypothesis about social networks’ differential effect for the age groups. As the effects of social environments change over time, they are modeled as interactions with age (Plutzer, Reference Plutzer2002).

Results

Description of Differences Between Youth Groups

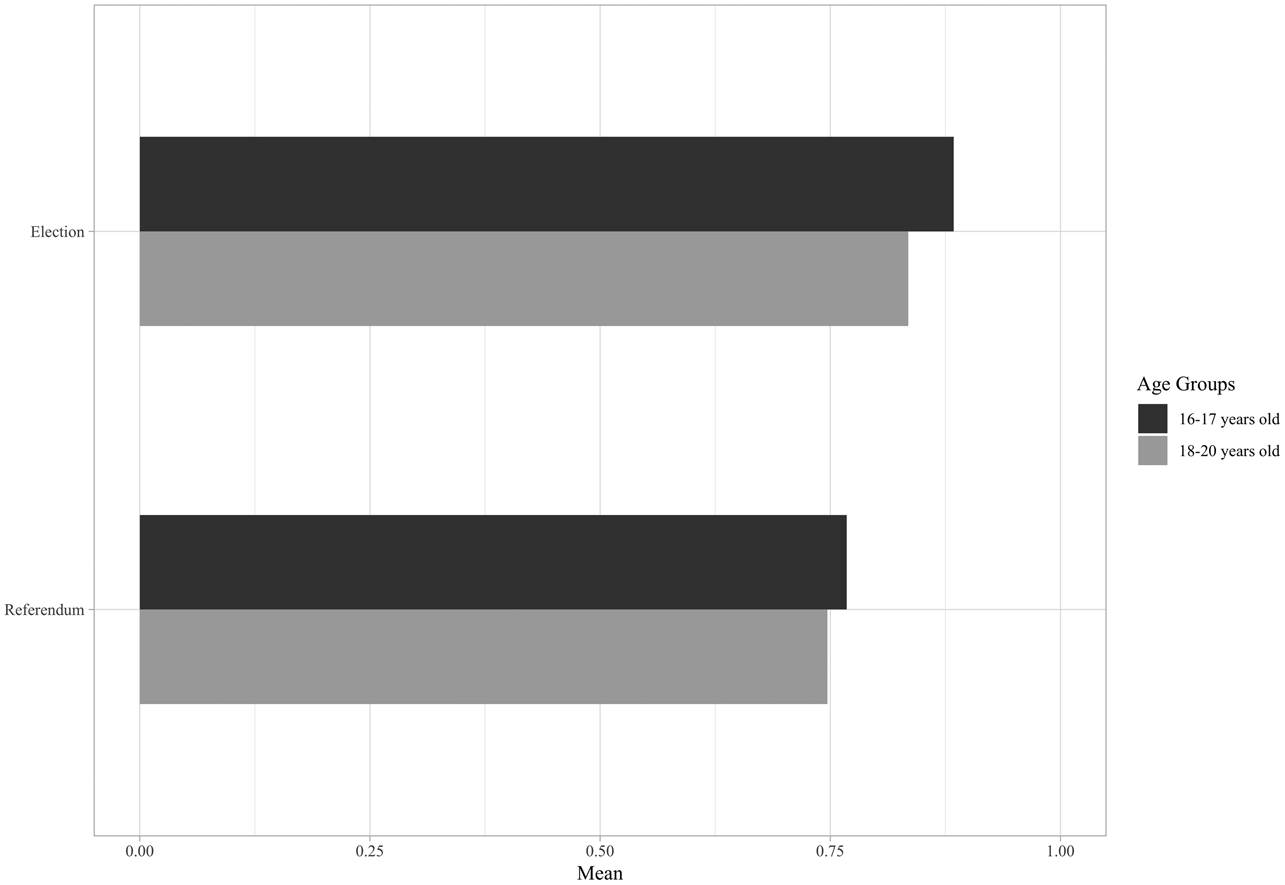

Our first research question asks whether underage youth are less motivated to be involved in politics than adult youth. Hence, we examine whether there are significant differences between these two groups in terms of their intended levels of political participation. Figure 1 illustrates the results from our opinion survey on intention to take part in an election and in a referendum. We observe that while underage youth are slightly more motivated to engage in these forms of participation, none of these intergroup differences are statistically significant.

Figure 1. Intentions to participate in a future election and referendum (mean scores and statistical differences between groups of youth). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Our second research question refers to differences in the political competencies of underage and adult youth to be effectively engaged in politics. We use four indicators to measure an individual's political preparedness. Figure 2 presents results associated with the first and second indicators of political preparedness: interest in politics and internal efficacy. The figure shows that the two age groups do not really differ from one another in terms of their levels of interest, but that adult youth present significantly higher levels of internal efficacy.

Figure 2. Levels of political interest and internal efficacy (mean scores and statistical differences between groups of youth). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Figure 3 presents the results for our third indicator of political preparedness: political knowledge. As can be seen from the two lower lines of the figure, the two age groups do not significantly differ in terms of their levels of knowledge about the election campaign. They are about equally likely to correctly associate campaign slogans and promises to their corresponding parties. In other words, they are about as equally “equipped” in terms of campaign-related knowledge. The story is a little different when we examine levels of factual political knowledge. As we observe from the top two lines in Figure 3, there is no difference between each group's ability to correctly identify political figures, but there is a statistically significant difference in knowledge of political institutions. Indeed, underage youth are better able to correctly attribute policy responsibilities to different levels of government. This might be partly explained by the fact that this knowledge is “fresher” in the memory of the 16- to 17-year-olds, having recently learned this in high school.

Figure 3. Levels of political knowledge (mean scores and statistical differences between groups of youth). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Our fourth indicator of political preparedness is the cohesion of youth's policy preferences. One way of assessing attitudinal consistency is to run a correlational analysis using a series of survey questions tapping aspects of a same policy issue. We do so here using two policy issues: the role of the state and immigration. The top rows of Table 1 presents the results of this first correlational analysis using three questions on state intervention. They indicate that opinions on these questions correlate with each other in a similar fashion in both groups, as none of the three correlation coefficients are significantly different from one age group to the other. So the two groups do not differ in terms of the consistency of their attitudes vis-à-vis state intervention.

Table 1. Correlational Analyses

Note: Entries are Pearson's r coefficients. The statistical significance of intergroup differences in the r value is calculated via Fisher Z-transformation; **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Correlation results obtained with the eight survey questions on immigration are displayed in the lower part of Table 1. The results indicate that attitudinal cohesion on this policy theme is slightly greater among the 18- to 20-year-olds. More precisely, the values of correlation coefficients are significantly larger for this group than for the 16- to 17-year-olds, for three pairs of survey items. We observe larger correlations between ‘being against a ban on religious signs by public sector employees’ with both ‘disagreeing that there are too many immigrants’ and ‘liking ethnocultural minorities.’ We also observe a larger correlation among the 18- to 20-year-olds between ‘liking immigrants’ and ‘disagreeing with the idea that speaking French should be a requirement for immigration’. These results can be interpreted as a sign of greater attitudinal sophistication on the part of adult youth, although intergroup differences on all the other pairs of immigration-related attitudes are not statistically significant.

To summarize the findings related to RQ2, we do not find consistent differences between 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds across all indicators. While adult youth display higher levels of internal efficacy and more constrained attitudes on the issue of immigration, underage youth are more knowledgeable about institutions. The two youth groups are not really different in terms of their levels of political interest, knowledge about the electoral campaign, or consistency of their attitudes on the role of the state. This lack of difference on many of our indicators is striking, given that underage youths are not yet eligible to vote and currently have fewer incentives to be politically engaged than enfranchised adult youths.

Multivariate Analyses

Table 2 presents multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) regression modelsFootnote 4 that provide a further test of the intergroup differences in political participation that we presented above, with the addition of control variables and individual resources variables.Footnote 5 The results of this table first confirm that a statistically significant difference exists between the two age groups, but only for one form of participation: underage youth display a greater propensity to participate in future elections. The models also underline that, among individual resources, political interest and factual knowledge are systematically linked to greater political engagement, while internal efficacy is not associated with it at all. So we find that interest and factual knowledge constitute important political competencies that positively affect youth's participation; but note that in the bivariate analyses we had not found much difference between youth groups on these two competency variables. Overall, these results offer a first indication that lowering the voting age would likely not hinder levels of participation—to the contrary.

Table 2. Multivariate OLS Regressions: Political Participation

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

The next step in our analysis is to test hypothesis H1, according to which youth's social resources constitute an additional motivation for them to engage with politics and perhaps compensate for their relative lack of political resources. It is useful first to provide a picture of youth's social resources as measured in our survey and to see whether the two groups of youth differ in that regard. Figure 4 presents the extent to which youth interacted with a candidate during the campaign, watched a leaders’ debate, and attended a debate at school. The intergroup differences on these indicators are all statistically significant and reveal that adult youth were clearly more mobilized by candidates and more active during the campaign in terms of seeking out information, which was expected, given that this group had the possibility to cast a vote in that election, whereas the 16- to 17-year-olds did not. We can envision that, had the latter been eligible to vote, they would likely have engaged in the same information-seeking behaviour as the 18- to 20-year-olds.

Figure 4. Level of contact with political candidates and participation in political activities during the electoral campaign (mean scores and statistical differences between groups of youth). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Figure 5 presents the frequency of discussion about the election with various members of their entourage. The figure indicates that 16- to 17-year-olds and 18- to 20-year-olds do not speak to the same people. Underage youth discussed the election with their parents and their teachers significantly more so than adult youth did, whereas adult youth discussed it significantly more with their peers (but there is no statistically significant difference with other members of the family). This is an interesting difference between the two age groups in terms of who in their entourage has the most potential to influence their political competencies and engagement.

Figure 5. Frequency of political discussions with family members, professors, friends and parents during the electoral campaign (mean scores and statistical differences between groups of youth). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Are these differences reflected when we examine the impact of social resources on the three main indicators of political preparedness? To some extent, they are. The models presented in the first and fifth columns of Table 3 indicate that, in general, discussions with parents are significantly associated both with greater interest in politics and greater factual knowledge among youth. Discussions with friends are also linked to greater political interest, while discussions with professors and other family members increase factual knowledge. Watching a leaders’ debate is also associated with greater interest in politics. No other variable displays a statistically significant relationship with individual competencies, and we note in the third column that no variable displays a statistically significant coefficient in the internal efficacy model. These results thus confirm hypothesis H1, making it clear that social networks are indeed linked to improved political resources, thus having the potential to buttress youth's abilities to be politically engaged. However, one result should give us pause: the lack of impact of attending a political debate at school on youth's political competencies.

Table 3. Multivariate OLS Regressions: Political Competencies

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

The interaction models presented in the second, fourth, and sixth columns of Table 3, which allow us to investigate RQ3, do not reveal much in the way of difference between the two age groups. Two small differences related to discussions with professors and with parents turn out to be significant, but they run contrary to expectations. However, these results fail to be confirmed through further testing.Footnote 6

To test whether social resources are associated with youth's participation (H1), and more so for underage youth (RQ3), we add social resource variables and interaction terms between them and the underage dummy variable to the two models already presented in Table 2. These results are presented in Table 4. The clearer effect in these models is the one obtained for ‘discussions with friends’. This socialization indicator is significantly and positively linked with both participation variables, and its effect is similar for both age groups (that is, the interaction term testing for intergroup difference is not statistically significant). Note that none of the interaction terms are statistically significant in these models, indicating a lack of difference in effects between the two groups of youth. To sum up, the results partly support hypothesis H1, with a positive impact of discussions with peers on both forms of participation, but no impact for the other discussion variables. RQ3, however, is not supported by the results. Finally, again we find no significant effect in the mobilizing influence of attending a political debate at school.

Table 4. Multivariate OLS Regressions: Political Participation

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

Discussion and Conclusion

Discussions on reforming the voting age are increasingly taking place in Canada and other Western democracies. However, past studies on the potential value of this reform have produced only mixed findings. Hence, this study contributes to the debate on reform by looking at evidence from a new case study: Canada. While we presented evidence based on a survey fielded in the province of Quebec, we nonetheless feel confident that these results are representative of the broader Canadian reality.Footnote 7 Youth in Quebec, as in other provinces, are exposed to a provincial parliamentary system embedded in a federal system and to relatively similar civic education programs (aiming to boost youth's political knowledge, interest and motivation to take part in elections). This study additionally contributes to the literature on reform of the voting age by providing additional, survey-based empirical evidence on the comparability of underage and adult youth, with regard to their political preparedness and propensity to become involved in politics. More specifically, we tested one argument of reform critics—that underage youth are insufficiently politically equipped and unprepared to take part in elections—and one of reform supporters—that allowing youth to vote for the first time while they are living at home and are in school would pave the way for more electoral engagement. We find only partial support for both arguments.

The results show that underage youth are not consistently less politically sophisticated than adult youth, and, depending on the aspect being looked at, underage youth are sometimes more resourceful or as resourceful as adult youth. For example, they are more knowledgeable about political institutions and as politically interested as 18- to 20-year-olds. Furthermore, underage youth are no less motivated to participate in various forms of political activity. Based on these results, 16- to 17-year-olds should be at least as active as 18- to 20-year-olds if they were given the chance to vote.

Additionally, we corroborate the findings of previous studies and show that different types of social networks influence youth's psychological engagement with politics and their motivation to participate uniquely, and that discussions with peers are especially mobilizing for political action. However, we find that the influence of schools is nonexistent. These null results on school influence may reflect the fact that we only have one indicator—taking part in a debate activity at school—and that we do not consider the potential value of civics classes, nor the quality of discussions and the types of messages conveyed by teachers (Dalton, Reference Dalton2008; Eichhorn and Mycock, Reference Eichhorn and Mycock2015; Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2007). Finally, we find no evidence of a more supportive role of parents and schools for the development of political resources and engagement of underage youth than for adult youth. This might partly be explained by the delayed transition to adulthood and the fact that these youth now have a relatively similar life context.

Overall, these findings neither contradict the critics’ arguments nor do they fully support the advocates’ arguments for the lowering of the voting age to 16. In the context of weak evidence for both lines of arguments, we are thus cautious about advocating a change in the voting age. Also, this study has certain limitations, and further research is needed to inform more decisively the debate on the voting age. Perhaps the most important limitation relates to our empirical evidence for current levels of political resources and engagement, and the influence of social networks, in a context where 16- to 17-year-olds are not enfranchised while 18- to 20-year-olds have voting rights. Thus, we cannot speak directly to the relevant counterfactual: how competent or engaged would underage youth be if they had the right to vote? And like other studies before us, we cannot control for the fact that enfranchisement potentially has a direct effect on participation and engagement. In the Canadian context where 16- and 17-year-olds do not have the right to vote, underage youth have little incentive to be interested in electoral politics, so the comparison with adult youth is partially flawed (even if we use similar survey questions for both groups). That being said, it is remarkable (and quite encouraging for supporters of the reform) that we find in this study that underage youth—who are not yet eligible to vote and whose entourage has no concrete incentive yet to encourage them to be politically active—already appear to be as politically aware and informed as adult youth who are eligible to vote.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000232.